Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Click beetle

View on Wikipedia

| Click beetles Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

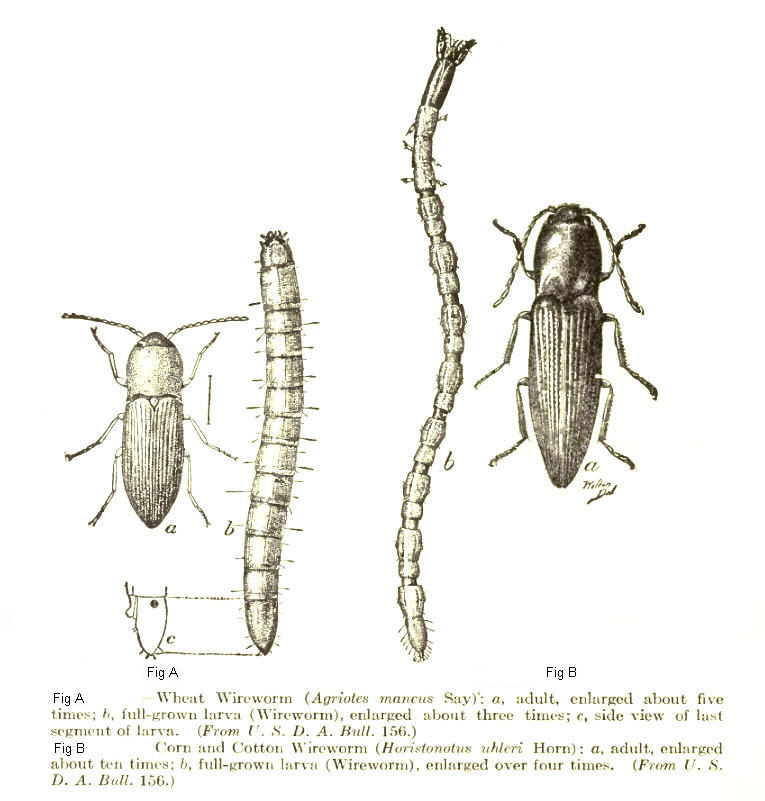

| Click beetle adults and larvae (wireworms) Left: Wheat wireworm (Agriotes mancus) Right: Sand wireworm (Horistonotus uhlerii) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Suborder: | Polyphaga |

| Infraorder: | Elateriformia |

| Superfamily: | Elateroidea |

| Family: | Elateridae Leach, 1815 |

| Subfamilies[2] | |

|

Agrypninae | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ampedidae | |

Elateridae or click beetles (or "typical click beetles" to distinguish them from the related families Cerophytidae and Eucnemidae, which are also capable of clicking) are a family of beetles. Other names include elaters, snapping beetles, spring beetles or skipjacks. This family was defined by William Elford Leach (1790–1836) in 1815. They are a cosmopolitan beetle family characterized by the unusual click mechanism they possess. There are a few other families of Elateroidea in which a few members have the same mechanism, but most elaterid subfamilies can click. A spine on the prosternum can be snapped into a corresponding notch on the mesosternum, producing a violent "click" that can bounce the beetle into the air.[3] The evolutionary purpose of this click is debated: hypotheses include that the clicking noise deters predators or is used for communication, or that the click may allow the beetle to "pop" out of the substrate in which it is pupating.[4] It is unlikely that the click is used for avoiding predators as it does not carry the beetle very far (<50 cm), and in practice click beetles usually play dead or flee normally.[4] There are about 9300 known species worldwide,[5] and 965 valid species in North America.[6]

Etymology

[edit]Leach took the family name from the genus Elater, coined by Linnaeus in 1758. In Greek, ἐλατήρ means one who drives, pushes, or beats out.[7] It is also the origin of the word "elastic", from the notion of beating out a ductile substance.[8]

Description and ecology

[edit]Some click beetles are large and colorful, but most are under two centimeters long and brown or black, without markings. The adults are typically nocturnal and phytophagous, but only some are of economic importance. On hot nights they may enter houses, but are not pests there. Click beetle larvae, called wireworms, are usually saprophagous, living on dead organisms, but some species are serious agricultural pests, and others are active predators of other insect larvae. Some elaterid species are bioluminescent in both larval and adult form, such as those of the genus Pyrophorus.

Wireworms

[edit]Larvae are elongate, cylindrical or somewhat flattened, with hard bodies, somewhat resembling mealworms. The three pairs of legs on the thoracic segments are short and the last abdominal segment is, as is frequently the case in beetle larvae, directed downward and may serve as a terminal proleg in some species.[9] The ninth segment, the rearmost, is pointed in larvae of Agriotes, Dalopius and Melanotus, but is bifid due to a so-called caudal notch in Selatosomus (formerly Ctenicera), Limonius, Hypnoides and Athous species.[10] The dorsum of the ninth abdominal segment may also have sharp processes, such as in the Oestodini, including the genera Drapetes and Oestodes. Although some species complete their development in one year (e.g. Conoderus), most wireworms spend three or four years in the soil, feeding on decaying vegetation and the roots of plants, and often causing damage to agricultural crops such as potato, strawberry, maize, and wheat.[11][12] The subterranean habits of wireworms, their ability to quickly locate food by following carbon dioxide gradients produced by plant material in the soil,[13] and their remarkable ability to recover from illness induced by insecticide exposure (sometimes after many months),[14] make it hard to exterminate them once they have begun to attack a crop. Wireworms can pass easily through the soil on account of their shape and their propensity for following pre-existing burrows,[15] and can travel from plant to plant, thus injuring the roots of multiple plants within a short time. Methods for pest control include crop rotation and clearing the land of insects before sowing.

Other subterranean creatures such as the leatherjacket grub of crane flies which have no legs, and geophilid centipedes, which may have over two hundred, are sometimes confused with the six-legged wireworms.[9]

Clicking ability

[edit]The ability of click beetles to "click" their bodies, sometimes launching themselves into the air, has been studied in detail.[4] It has three stages—the pre-jump stage, the takeoff stage, and the airborne stage.[4] The beetle is supine, on its back, in the pre-jump stage, and over ~2-3s it rotates its prothorax (foremost section) down to touch the ground in a bracing position.[4] In the takeoff phase the prothorax rotates rapidly upward in a "snap", launching the beetle off of the ground and ballistically into the air.[4] Crucially, the beetle uses specialized mechanisms to hold itself in the bracing position while its muscles continue to contract, until it releases the tension in one "snap".[4]

Evolution and taxonomy

[edit]The oldest known species date to the Triassic, but most are problematic due to only being known from isolated elytra. Many fossil elaterids belong to the extinct subfamily Protagrypninae.[16]

Approximately 20 subfamilies are included in the Elateridae, considered typical of beetles in the superfamily Elateroidea;[17] authorities have moved genera from related families (e.g. "false click beetles" to the Thylacosterninae[18]).

Thylacosterninae

[edit]Authority: Fleutiaux, 1920

- Balgus Fleutiaux, 1920

- Cussolenis Fleutiaux, 1918

- Pterotarsus Guérin-Méneville

- Thylacosternus Gemminger, 1869

Other selected genera

[edit]- Actenicerus

- Adelocera

- Adrastus

- Aeoloderma

- Aeoloides

- Aeolus

- Agriotes

- Agrypnus

- Alaus

- Ampedus

- Anchastus

- Anostirus

- Aplotarsus

- Athous

- Betarmon

- Brachygonus

- Brachylacon

- Brongniartia

- Calambus

- Cardiophorus

- Cebrio

- Chalcolepidus

- Cidnopus

- Conoderus

- Craspedostethus

- Crepidophorus

- Ctenicera

- Dacnitus

- Dalopius

- Danosoma

- Deilelater

- Diacanthous

- Dicronychus

- Dima

- Drilus

- Eanus

- Ectamenogonus

- Ectinus

- Elater

- Elathous

- Eopenthes

- Fleutiauxellus

- Haterumelater

- Hemicleus

- Hemicrepidius

- Heteroderes

- Horistonotus

- Hypnoidus

- Hypoganus

- Hypolithus

- Idolus

- Ignelater

- Ischnodes

- Isidus

- Itodacne

- Jonthadocerus

- Lacon

- Lanelater

- Limoniscus

- Limonius

- Liotrichus

- Megapenthes

- Melanotus

- Melanoxanthus

- Metanomus

- Merklelater

- Mulsanteus

- Negastrius

- Neopristilophus

- Nothodes

- Oedostethus

- Orithales

- Paracardiophorus

- Paraphotistus

- Peripontius

- Pheletes

- Pittonotus

- Pityobius

- Podeonius

- Porthmidius

- Procraerus

- Prodrasterius

- Prosternon

- Pyrearinus

- Pyrophorus

- Quasimus

- Reitterelater

- Selatosomus

- Semiotinus

- Semiotus

- Sericus

- Simodactylus

- Spheniscosomus

- Stenagostus

- Synaptus

- Vesperelater

- Zorochros

Gallery

[edit]-

Click beetle in Japan

-

Alaus oculatus on a potato plant in an Oklahoma garden

-

Lateral aspect of a typical member of the Elateridae. Just below the base of the wings the "clicking" apparatus is visible in silhouette, with the "peg" or "process" in contact with the raised slot or "cavity" into which it slips to force the impact when required.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Kusy, Dominik; Motyka, Michal; Bocek, Matej; Vogler, Alfried P.; Bocak, Ladislav (2018-11-20). "Genome sequences identify three families of Coleoptera as morphologically derived click beetles (Elateridae)". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 17084. Bibcode:2018NatSR...817084K. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35328-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6244081. PMID 30459416.

- ^ Robin Kundrata, Nicole L. Gunter, Dominika Janosikova & Ladislav Bocak (2018) Molecular evidence for the subfamilial status of Tetralobinae (Coleoptera: Elateridae), with comments on parallel evolution of some phenotypic characters. Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 76: 137–145. doi:10.3897/asp.76.e31946

- ^ How the click beetle jumps from the back !. Myrmecofourmis.fr on Youtube. 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bolmin, Ophelia; Wei, Lihua; Hazel, Alexander M.; Dunn, Alison C.; Wissa, Aimy; Alleyne, Marianne (2019-06-17). "Latching of the click beetle (Coleoptera: Elateridae) thoracic hinge enabled by the morphology and mechanics of conformal structures". Journal of Experimental Biology. 222 (12): jeb196683. doi:10.1242/jeb.196683. ISSN 0022-0949.

- ^ Schneider, M. C.; et al. (2006). "Evolutionary chromosomal differentiation among four species of Conoderus Eschscholtz, 1829 (Coleoptera, Elateridae, Agrypninae, Conoderini) detected by standard staining, C-banding, silver nitrate impregnation, and CMA3/DA/DAPI staining". Genetica. 128 (1–3): 333–346. doi:10.1007/s10709-006-7101-5. PMID 17028962. S2CID 1901849.

- ^ Majka, C. G.; P. J. Johnson (2008). "The Elateridae (Coleoptera) of the Maritime Provinces of Canada: faunal composition, new records, and taxonomic changes" (PDF excerpt). Zootaxa. 1811: 1–33. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1811.1.1.

- ^ Wiktionary - "elater"

- ^ Wiktionary - "elastic"

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wireworm". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 739.

- ^ van Herk, W. (March 12, 2009). "Limonius: wireworm research site". Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ R. S. Vernon; W. van Herk; J. Tolman; H. Ortiz Saavedra; M. Clodius; B. Gage (2008). "Transitional sublethal and lethal effects of insecticides after dermal exposures to five economic species of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae)". Journal of Economic Entomology. 101 (2): 365–374. doi:10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[365:TSALEO]2.0.CO;2. PMID 18459400.

- ^ William E. Parker; Julia J. Howard (2001). "The biology and management of wireworms (Agriotes spp.) on potato with particular reference to the U.K.". Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 3 (2): 85–98. doi:10.1046/j.1461-9563.2001.00094.x.

- ^ J. F. Doane; Y. W. Lee; N. D. Westcott; J. Klingler (1975). "The orientation response of Ctenicera destructor and other wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) to germinating grain and to carbon dioxide". Canadian Entomologist. 107 (12): 1233–1252. doi:10.4039/Ent1071233-12.

- ^ W. G. van Herk; R. S. Vernon; J. H. Tolman; H. Ortiz Saavedra (2008). "Mortality of a wireworm, Agriotes obscurus (Coleoptera: Elateridae), after topical application of various insecticides". Journal of Economic Entomology. 101 (2): 375–383. doi:10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[375:moawao]2.0.co;2. PMID 18459401.

- ^ Willem G. van Herk; Robert S. Vernon (2007). "Soil bioassay for studying behavioral responses of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) to inecticide-treated wheat seed". Environmental Entomology. 36 (6): 1441–1449. doi:10.1603/0046-225X(2007)36[1441:SBFSBR]2.0.CO;2. PMID 18284772.

- ^ Kundrata, Robin; Packova, Gabriela; Hoffmannova, Johana (2020-06-26). "Fossil Genera in Elateridae (Insecta, Coleoptera): A Triassic Origin and Jurassic Diversification". Insects. 11 (6): 394. doi:10.3390/insects11060394. ISSN 2075-4450. PMC 7348820. PMID 32604761.

- ^ BioLib.cz: click beetles Elateridae Leach, 1815 (retrieved 5 January 2025)

- ^ Barbosa, F.F. (2016) Revision and phylogeny of the genus Balgus Fleutiaux, 1920 (Coleoptera, Elateridae, Thylacosterninae). Zootaxa 4083(4): 451–482. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4083.4.1

References

[edit]- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

External links

[edit] Media related to Elateridae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elateridae at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Click beetle at Wikispecies

Data related to Click beetle at Wikispecies- Elateridae. Click Beetles of the Palearctic Region.

On the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures website: