Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coagulation

View on Wikipedia

| Coagulation | |

|---|---|

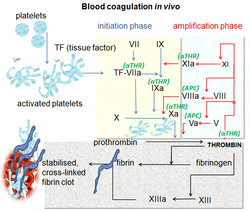

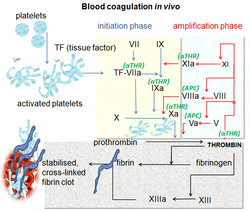

Blood coagulation pathways in vivo showing the central role played by thrombin | |

| Health | Beneficial |

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of coagulation involves activation, adhesion and aggregation of platelets, as well as deposition and maturation of fibrin.

Coagulation begins almost instantly after an injury to the endothelium that lines a blood vessel. Exposure of blood to the subendothelial space initiates two processes: changes in platelets, and the exposure of subendothelial platelet tissue factor to coagulation factor VII, which ultimately leads to cross-linked fibrin formation. Platelets immediately form a plug at the site of injury; this is called primary hemostasis. Secondary hemostasis occurs simultaneously: additional coagulation factors beyond factor VII (listed below) respond in a cascade to form fibrin strands, which strengthen the platelet plug.[1]

Coagulation is highly conserved throughout biology. In all mammals, coagulation involves both cellular components (platelets) and proteinaceous components (coagulation or clotting factors).[2][3] The pathway in humans has been the most extensively researched and is the best understood.[4] Disorders of coagulation can result in problems with hemorrhage, bruising, or thrombosis.[5]

List of coagulation factors

[edit]There are 13 traditional clotting factors, as named below,[6] and other substances necessary for coagulation:

| Number/Name | Synonym(s) | Function | Associated genetic disorders | Type of molecule | Source | Pathway(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor I | Fibrinogen | Forms fibrin threads in blood clots | Plasma protein | Liver | Common pathway; converted into fibrin | |

| Factor II* | Prothrombin | Its active form (IIa) activates platelets, factors I, V, VII, VIII, XI, XIII, protein C |

|

Plasma protein | Liver | Common pathway; converted into thrombin |

| Factor III |

|

Co-factor of factor VIIa, which was formerly known as factor III | Lipoprotein mixture | Damaged cells and platelets | Extrinsic | |

| Factor IV |

|

Required for coagulation factors to bind to phospholipids, which were formerly known as factor IV | Inorganic ions in plasma | Diet, platelets, bone matrix | Entire process of coagulation | |

| Factor V |

|

Co-factor of factor X with which it forms the prothrombinase complex | Activated protein C resistance | Plasma protein | Liver, platelets | Extrinsic and intrinsic |

| Factor VI |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Factor VII* |

|

Activates factors IX, X; increases rate of catalytic conversion of prothrombin into thrombin | Congenital factor VII deficiency | Plasma protein | Liver | Extrinsic |

| Factor VIII |

|

Co-factor of factor IX with which it forms the tenase complex | Hemophilia A | Plasma protein factor | Platelets and endothelial cells | Intrinsic |

| Factor IX* |

|

Activates factor X, forms tenase complex with factor VIII | Hemophilia B | Plasma protein | Liver | Intrinsic |

| Factor X* |

|

Activates factor II, forms prothrombinase complex with factor V | Congenital Factor X deficiency | Protein | Liver | Extrinsic and intrinsic |

| Factor XI |

|

Activates factor IX | Hemophilia C | Plasma protein | Liver | Intrinsic |

| Factor XII | Hageman factor | Activates XI, VII, prekallikrein and plasminogen | Hereditary angioedema type III | Plasma protein | Liver | Intrinsic; initiates clotting in vitro; also activates plasmin |

| Factor XIII | Fibrin-stabilizing factor | Crosslinks fibrin threads | Congenital factor XIIIa/b deficiency | Plasma protein | Liver, platelets | Common pathway; stabilizes fibrin; slows down fibrinolysis |

| Vitamin K | Clotting vitamin | Essential factor to the hepatic gamma-glutamyl carboxylase that adds a carboxyl group to glutamic acid residues on factors II, VII, IX and X, as well as Protein S, Protein C and Protein Z[8] | Vitamin K deficiency | Phytyl-substituted naphthoquinone derivative | Gut microbiota (e.g. E. coli[9]), dietary sources |

Extrinsic[10] |

| von Willebrand factor | Binds to VIII, mediates platelet adhesion | von Willebrand disease | Blood glycoprotein | Blood vessels' endothelia, bone marrow[11] |

||

| Prekallikrein | Fletcher factor | Activates XII and prekallikrein; cleaves HMWK | Prekallikrein/Fletcher factor deficiency | |||

| Kallikrein | Activates plasminogen | |||||

| High-molecular-weight kininogen |

|

Supports reciprocal activation of factors XII, XI, and prekallikrein | Kininogen deficiency | |||

| Fibronectin | Mediates cell adhesion | Glomerulopathy with fibronectin deposits | ||||

| Antithrombin III | Inhibits factors IIa, Xa, IXa, XIa, and XIIa | Antithrombin III deficiency | ||||

| Heparin cofactor II | Inhibits factor IIa, cofactor for heparin and dermatan sulfate ("minor antithrombin") | Heparin cofactor II deficiency | ||||

| Protein C | Inactivates factors Va and VIIIa | Protein C deficiency | ||||

| Protein S | Cofactor for activated protein C (APC, inactive when bound to C4b-binding protein | Protein S deficiency | ||||

| Protein Z | Mediates thrombin adhesion to phospholipids and stimulates degradation of factor X by ZPI | Protein Z deficiency | ||||

| Protein Z-related protease inhibitor | ZPI | Degrades factors X (in presence of protein Z) and XI (independently | ||||

| Plasminogen | Converts to plasmin, lyses fibrin and other proteins | Plasminogen deficiency type I (ligneous conjunctivitis) | ||||

| α2-Antiplasmin | Inhibits plasmin | Antiplasmin deficiency | ||||

| α2-Macroglobulin | Inhibits plasmin, kallikrein, and thrombin | |||||

| Tissue plasminogen activator | t-PA or TPA | Activates plasminogen |

| |||

| Urokinase | Activates plasminogen | Quebec platelet disorder | ||||

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 | PAI-1 | Inactivates tPA and urokinase (endothelial PAI | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency | |||

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 | PAI-2 | Inactivates tPA and urokinase | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency | |||

| Cancer procoagulant | Pathological activator of factor X; linked to thrombosis in various cancers[12] | |||||

| * Vitamin K is required for biosynthesis of these clotting factors[8] | ||||||

Physiology

[edit]

Physiology of blood coagulation is based on hemostasis, the normal bodily process that stops bleeding. Coagulation is a part of an integrated series of haemostatic reactions, involving plasma, platelet, and vascular components.[13]

Hemostasis consists of four main stages:

- Vasoconstriction (vasospasm or vascular spasm): Here, this refers to contraction of smooth muscles in the tunica media layer of endothelium (blood vessel wall).

- Activation of platelets and platelet plug formation:

- Platelet activation: Platelet activators, such as platelet activating factor and thromboxane A2,[14] activate platelets in the bloodstream, leading to attachment of platelets' membrane receptors (e.g. glycoprotein IIb/IIIa[15]) to extracellular matrix[16] proteins (e.g. von Willebrand factor[17]) on cell membranes of damaged endothelial cells and exposed collagen at the site of injury.[18]

- Platelet plug formation: The adhered platelets aggregate and form a temporary plug to stop bleeding. This process is often called "primary hemostasis".[19]

- Coagulation cascade: It is a series of enzymatic reactions that lead to the formation of a stable blood clot. The endothelial cells release substances like tissue factor, which triggers the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade. This is called as "secondary hemostasis".[20]

- Fibrin clot formation: Near the end of the extrinsic pathway, after thrombin completes conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin,[21] factor XIIIa (plasma transglutaminase;[21] activated form of fibrin-stabilizing factor) promotes fibrin cross-linking, and subsequent stabilization of fibrin, leading to the formation of a fibrin clot (final blood clot), which temporarily seals the wound to allow wound healing until its inner part is dissolved by fibrinolytic enzymes, while the clot's outer part is shed off.

After the fibrin clot is formed, clot retraction occurs and then clot resolution starts, and these two process are together called "tertiary hemostasis". Activated platelets contract their internal actin and myosin fibrils in their cytoskeleton, which leads to shrinkage of the clot volume. Plasminogen activators, such as tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), activate plasminogen into plasmin, which promotes lysis of the fibrin clot; this restores the flow of blood in the damaged/obstructed blood vessels.[22]

Vasoconstriction

[edit]When there is an injury to a blood vessel, the endothelial cells can release various vasoconstrictor substances, such as endothelin[23] and thromboxane,[24] to induce the constriction of the smooth muscles in the vessel wall. This helps reduce blood flow to the site of injury and limits bleeding.

Platelet activation and platelet plug formation

[edit]When the endothelium is damaged, the normally isolated underlying collagen is exposed to circulating platelets, which bind directly to collagen with collagen-specific glycoprotein Ia/IIa surface receptors. This adhesion is strengthened further by von Willebrand factor (vWF), which is released from the endothelium and from platelets; vWF forms additional links between the platelets' glycoprotein Ib/IX/V and A1 domain. This localization of platelets to the extracellular matrix promotes collagen interaction with platelet glycoprotein VI. Binding of collagen to glycoprotein VI triggers a signaling cascade that results in activation of platelet integrins. Activated integrins mediate tight binding of platelets to the extracellular matrix. This process adheres platelets to the site of injury.[25]

Activated platelets release the contents of stored granules into the blood plasma. The granules include ADP, serotonin, platelet-activating factor (PAF), vWF, platelet factor 4, and thromboxane A2 (TXA2), which, in turn, activate additional platelets. The granules' contents activate a Gq-linked protein receptor cascade, resulting in increased calcium concentration in the platelets' cytosol. The calcium activates protein kinase C, which, in turn, activates phospholipase A2 (PLA2). PLA2 then modifies the integrin membrane glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, increasing its affinity to bind fibrinogen. The activated platelets change shape from spherical to stellate, and the fibrinogen cross-links with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa aid in aggregation of adjacent platelets, forming a platelet plug and thereby completing primary hemostasis).[26]

Coagulation cascade

[edit]

The coagulation cascade of secondary hemostasis has two initial pathways which lead to fibrin formation. These are the contact activation pathway (also known as the intrinsic pathway), and the tissue factor pathway (also known as the extrinsic pathway), which both lead to the same fundamental reactions that produce fibrin. It was previously thought that the two pathways of coagulation cascade were of equal importance, but it is now known that the primary pathway for the initiation of blood coagulation is the tissue factor (extrinsic) pathway. The pathways are a series of reactions, in which a zymogen (inactive enzyme precursor) of a serine protease and its glycoprotein co-factor are activated to become active components that then catalyze the next reaction in the cascade, ultimately resulting in cross-linked fibrin. Coagulation factors are generally indicated by Roman numerals, with a lowercase a appended to indicate an active form.[27]

The coagulation factors are generally enzymes called serine proteases, which act by cleaving downstream proteins. The exceptions are tissue factor, FV, FVIII, FXIII.[28] Tissue factor, FV and FVIII are glycoproteins, and Factor XIII is a transglutaminase.[27] The coagulation factors circulate as inactive zymogens. The coagulation cascade is therefore classically divided into three pathways. The tissue factor and contact activation pathways both activate the "final common pathway" of factor X, thrombin and fibrin.[29]

Tissue factor pathway (extrinsic)

[edit]The main role of the tissue factor (TF) pathway is to generate a "thrombin burst", a process by which thrombin, the most important constituent of the coagulation cascade in terms of its feedback activation roles, is released very rapidly. FVIIa circulates in a higher amount than any other activated coagulation factor. The process includes the following steps:[27]

- Following damage to the blood vessel, FVII leaves the circulation and comes into contact with tissue factor expressed on tissue-factor-bearing cells (stromal fibroblasts and leukocytes), forming an activated complex (TF-FVIIa).

- TF-FVIIa activates FIX and FX.

- FVII is itself activated by thrombin, FXIa, FXII, and FXa.

- The activation of FX (to form FXa) by TF-FVIIa is almost immediately inhibited by tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI).

- FXa and its co-factor FVa form the prothrombinase complex, which activates prothrombin to thrombin.

- Thrombin then activates other components of the coagulation cascade, including FV and FVIII (which forms a complex with FIX), and activates and releases FVIII from being bound to vWF.

- FVIIIa is the co-factor of FIXa, and together they form the "tenase" complex, which activates FX; and so the cycle continues. ("Tenase" is a contraction of "ten" and the suffix "-ase" used for enzymes.)

Contact activation pathway (intrinsic)

[edit]The contact activation pathway begins with formation of the primary complex on collagen by high-molecular-weight kininogen (HMWK), prekallikrein, and FXII (Hageman factor). Prekallikrein is converted to kallikrein and FXII becomes FXIIa. FXIIa converts FXI into FXIa. Factor XIa activates FIX, which with its co-factor FVIIIa form the tenase complex, which activates FX to FXa. The minor role that the contact activation pathway has in initiating blood clot formation (or more specifically, physiological hemostasis) can be illustrated by the fact that individuals with severe deficiencies of FXII, HMWK, and prekallikrein do not have a bleeding disorder. Instead, contact activation system seems to be more involved in inflammation,[27] and innate immunity.[30] Interference with the pathway may confer protection against thrombosis without a significant bleeding risk.[30]

Inhibition of factor XII and PK interferes with innate immunity in animal models.[30] More promising is inhibition of factor XI, which in early clinical trials have shown the expected effect.[31]

Final common pathway

[edit]The division of coagulation in two pathways is arbitrary, originating from laboratory tests in which clotting times were measured either after the clotting was initiated by glass, the intrinsic pathway; or clotting was initiated by thromboplastin (a mix of tissue factor and phospholipids), the extrinsic pathway.[32]

Further, the final common pathway scheme implies that prothrombin is converted to thrombin only when acted upon by the intrinsic or extrinsic pathways, which is an oversimplification. In fact, thrombin is generated by activated platelets at the initiation of the platelet plug, which in turn promotes more platelet activation.[33]

Thrombin functions not only to convert fibrinogen to fibrin, it also activates Factors VIII and V and their inhibitor protein C (in the presence of thrombomodulin). By activating Factor XIII, covalent bonds are formed that crosslink the fibrin polymers that form from activated monomers.[27] This stabilizes the fibrin network.[34]

The coagulation cascade is maintained in a prothrombotic state by the continued activation of FVIII and FIX to form the tenase complex until it is down-regulated by the anticoagulant pathways.[27]

Cell-based scheme of coagulation

[edit]A newer model of coagulation mechanism explains the intricate combination of cellular and biochemical events that occur during the coagulation process in vivo. Along with the procoagulant and anticoagulant plasma proteins, normal physiologic coagulation requires the presence of two cell types for formation of coagulation complexes: cells that express tissue factor (usually extravascular) and platelets.[35]

The coagulation process occurs in two phases. First is the initiation phase, which occurs in tissue-factor-expressing cells. This is followed by the propagation phase, which occurs on activated platelets. The initiation phase, mediated by the tissue factor exposure, proceeds via the classic extrinsic pathway and contributes to about 5% of thrombin production. The amplified production of thrombin occurs via the classic intrinsic pathway in the propagation phase; about 95% of thrombin generated will be during this second phase.[36]

Fibrinolysis

[edit]Eventually, blood clots are reorganized and resorbed by a process termed fibrinolysis. The main enzyme responsible for this process is plasmin, which is regulated by plasmin activators and plasmin inhibitors.[37]

Role in immune system

[edit]The coagulation system overlaps with the immune system. Coagulation can physically trap invading microbes in blood clots. Also, some products of the coagulation system can contribute to the innate immune system by their ability to increase vascular permeability and act as chemotactic agents for phagocytic cells. In addition, some of the products of the coagulation system are directly antimicrobial. For example, beta-lysine, an amino acid produced by platelets during coagulation, can cause lysis of many Gram-positive bacteria by acting as a cationic detergent.[38] Many acute-phase proteins of inflammation are involved in the coagulation system. In addition, pathogenic bacteria may secrete agents that alter the coagulation system, e.g. coagulase and streptokinase.[39]

Immunohemostasis is the integration of immune activation into adaptive clot formation. Immunothrombosis is the pathological result of crosstalk between immunity, inflammation, and coagulation. Mediators of this process include damage-associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which are recognized by toll-like receptors, triggering procoagulant and proinflammatory responses such as formation of neutrophil extracellular traps.[40]

Cofactors

[edit]Various substances are required for the proper functioning of the coagulation cascade:

Calcium and phospholipids

[edit]Calcium and phospholipids (constituents of platelet membrane) are required for the tenase and prothrombinase complexes to function.[41] Calcium mediates the binding of the complexes via the terminal gamma-carboxy residues on Factor Xa and Factor IXa to the phospholipid surfaces expressed by platelets, as well as procoagulant microparticles or microvesicles shed from them.[42] Calcium is also required at other points in the coagulation cascade. Calcium ions play a major role in the regulation of coagulation cascade that is paramount in the maintenance of hemostasis. Other than platelet activation, calcium ions are responsible for complete activation of several coagulation factors, including coagulation Factor XIII.[43]

Vitamin K

[edit]Vitamin K is an essential factor to the hepatic gamma-glutamyl carboxylase that adds a carboxyl group to glutamic acid residues on factors II, VII, IX and X, as well as Protein S, Protein C and Protein Z. In adding the gamma-carboxyl group to glutamate residues on the immature clotting factors, Vitamin K is itself oxidized. Another enzyme, Vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKORC), reduces vitamin K back to its active form. Vitamin K epoxide reductase is pharmacologically important as a target of anticoagulant drugs warfarin and related coumarins such as acenocoumarol, phenprocoumon, and dicumarol. These drugs create a deficiency of reduced vitamin K by blocking VKORC, thereby inhibiting maturation of clotting factors. Vitamin K deficiency from other causes (e.g., in malabsorption) or impaired vitamin K metabolism in disease (e.g., in liver failure) lead to the formation of PIVKAs (proteins formed in vitamin K absence), which are partially or totally non-gamma carboxylated, affecting the coagulation factors' ability to bind to phospholipid.[44]

Regulators

[edit]

Several mechanisms keep platelet activation and the coagulation cascade in check.[45] Abnormalities can lead to an increased tendency toward thrombosis:

Protein C and Protein S

[edit]Protein C is a major physiological anticoagulant. It is a vitamin K-dependent serine protease enzyme that is activated by thrombin into activated protein C (APC). Protein C is activated in a sequence that starts with Protein C and thrombin binding to a cell surface protein thrombomodulin. Thrombomodulin binds these proteins in such a way that it activates Protein C. The activated form, along with protein S and a phospholipid as cofactors, degrades FVa and FVIIIa. Quantitative or qualitative deficiency of either (protein C or protein S) may lead to thrombophilia (a tendency to develop thrombosis). Impaired action of Protein C (activated Protein C resistance), for example by having the "Leiden" variant of Factor V or high levels of FVIII, also may lead to a thrombotic tendency.[45]

Antithrombin

[edit]Antithrombin is a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) that degrades the serine proteases: thrombin, FIXa, FXa, FXIa, and FXIIa. It is constantly active, but its adhesion to these factors is increased by the presence of heparan sulfate (a glycosaminoglycan) or the administration of heparins (different heparinoids increase affinity to FXa, thrombin, or both). Quantitative or qualitative deficiency of antithrombin (inborn or acquired, e.g., in proteinuria) leads to thrombophilia.[45]

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI)

[edit]Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) limits the action of tissue factor (TF). It also inhibits excessive TF-mediated activation of FVII and FX.[46]

Plasmin

[edit]Plasmin is generated by proteolytic cleavage of plasminogen, a plasma protein synthesized in the liver. This cleavage is catalyzed by tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), which is synthesized and secreted by endothelium. Plasmin proteolytically cleaves fibrin into fibrin degradation products that inhibit excessive fibrin formation.[citation needed]

Prostacyclin

[edit]Prostacyclin (PGI2) is released by endothelium and activates platelet Gs protein-linked receptors. This, in turn, activates adenylyl cyclase, which synthesizes cAMP. cAMP inhibits platelet activation by decreasing cytosolic levels of calcium and, by doing so, inhibits the release of granules that would lead to activation of additional platelets and the coagulation cascade.[37]

Medical assessment

[edit]Numerous medical tests are used to assess the function of the coagulation system:[3][47]

- Common: aPTT, PT (also used to determine INR), fibrinogen testing (often by the Clauss fibrinogen assay),[48] platelet count, platelet function testing (often by PFA-100), thrombodynamics test.

- Other: TCT, bleeding time, mixing test (whether an abnormality corrects if the patient's plasma is mixed with normal plasma), coagulation factor assays, antiphospholipid antibodies, D-dimer, genetic tests (e.g. factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation G20210A), dilute Russell's viper venom time (dRVVT), miscellaneous platelet function tests, thromboelastography (TEG or Sonoclot), euglobulin lysis time (ELT).

The contact activation (intrinsic) pathway is initiated by activation of the contact activation system, and can be measured by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) test.[49]

The tissue factor (extrinsic) pathway is initiated by release of tissue factor (a specific cellular lipoprotein), and can be measured by the prothrombin time (PT) test.[50] PT results are often reported as ratio (INR value) to monitor dosing of oral anticoagulants such as warfarin.[51]

The quantitative and qualitative screening of fibrinogen is measured by the thrombin clotting time (TCT). Measurement of the exact amount of fibrinogen present in the blood is generally done using the Clauss fibrinogen assay.[48] Many analysers are capable of measuring a "derived fibrinogen" level from the graph of the Prothrombin time clot.

If a coagulation factor is part of the contact activation or tissue factor pathway, a deficiency of that factor will affect only one of the tests: Thus hemophilia A, a deficiency of factor VIII, which is part of the contact activation pathway, results in an abnormally prolonged aPTT test but a normal PT test. Deficiencies of common pathway factors prothrombin, fibrinogen, FX, and FV will prolong both aPTT and PT. If an abnormal PT or aPTT is present, additional testing will occur to determine which (if any) factor is present as aberrant concentrations.

Deficiencies of fibrinogen (quantitative or qualitative) will prolong PT, aPTT, thrombin time, and reptilase time.

Role in disease

[edit]Coagulation defects may cause hemorrhage or thrombosis, and occasionally both, depending on the nature of the defect.[52]

Platelet disorders

[edit]Platelet disorders are either congenital or acquired. Examples of congenital platelet disorders are Glanzmann's thrombasthenia, Bernard–Soulier syndrome (abnormal glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex), gray platelet syndrome (deficient alpha granules), and delta storage pool deficiency (deficient dense granules). Most are rare. They predispose to hemorrhage. Von Willebrand disease is due to deficiency or abnormal function of von Willebrand factor, and leads to a similar bleeding pattern; its milder forms are relatively common.[citation needed]

Decreased platelet numbers (thrombocytopenia) is due to insufficient production (e.g., myelodysplastic syndrome or other bone marrow disorders), destruction by the immune system (immune thrombocytopenic purpura), or consumption (e.g., thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia).[53] An increase in platelet count is called thrombocytosis, which may lead to formation of thromboembolisms; however, thrombocytosis may be associated with increased risk of either thrombosis or hemorrhage in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm.[54]

Coagulation factor disorders

[edit]The best-known coagulation factor disorders are the hemophilias. The three main forms are hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency), hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency or "Christmas disease") and hemophilia C (factor XI deficiency, mild bleeding tendency).[55]

Von Willebrand disease (which behaves more like a platelet disorder except in severe cases), is the most common hereditary bleeding disorder and is characterized as being inherited autosomal recessive or dominant. In this disease, there is a defect in von Willebrand factor (vWF), which mediates the binding of glycoprotein Ib (GPIb) to collagen. This binding helps mediate the activation of platelets and formation of primary hemostasis.[medical citation needed]

In acute or chronic liver failure, there is insufficient production of coagulation factors, possibly increasing risk of bleeding during surgery.[56]

Thrombosis is the pathological development of blood clots. These clots may break free and become mobile, forming an embolus or grow to such a size that occludes the vessel in which it developed. An embolism is said to occur when the thrombus (blood clot) becomes a mobile embolus and migrates to another part of the body, interfering with blood circulation and hence impairing organ function downstream of the occlusion. This causes ischemia and often leads to ischemic necrosis of tissue. Most cases of venous thrombosis are due to acquired states (older age, surgery, cancer, immobility). Unprovoked venous thrombosis may be related to inherited thrombophilias (e.g., factor V Leiden, antithrombin deficiency, and various other genetic deficiencies or variants), particularly in younger patients with family history of thrombosis; however, thrombotic events are more likely when acquired risk factors are superimposed on the inherited state.[57]

Pharmacology

[edit]Procoagulants

[edit]The use of adsorbent chemicals, such as zeolites, and other hemostatic agents are also used for sealing severe injuries quickly (such as in traumatic bleeding secondary to gunshot wounds). Thrombin and fibrin glue are used surgically to treat bleeding and to thrombose aneurysms. Hemostatic Powder Spray TC-325 is used to treated gastrointestinal bleeding.[citation needed]

Desmopressin is used to improve platelet function by activating arginine vasopressin receptor 1A.[58]

Coagulation factor concentrates are used to treat hemophilia, to reverse the effects of anticoagulants, and to treat bleeding in people with impaired coagulation factor synthesis or increased consumption. Prothrombin complex concentrate, cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma are commonly used coagulation factor products. Recombinant activated human factor VII is sometimes used in the treatment of major bleeding.

Tranexamic acid and aminocaproic acid inhibit fibrinolysis and lead to a de facto reduced bleeding rate. Before its withdrawal, aprotinin was used in some forms of major surgery to decrease bleeding risk and the need for blood products.

Anticoagulants

[edit]Anticoagulants and anti-platelet agents (together "antithrombotics") are amongst the most commonly used medications. Anti-platelet agents include aspirin, dipyridamole, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel; the parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used during angioplasty. Of the anticoagulants, warfarin (and related coumarins) and heparin are the most commonly used. Warfarin affects the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X) and protein C and protein S,[59] whereas heparin and related compounds increase the action of antithrombin on thrombin and factor Xa. A newer class of drugs, the direct thrombin inhibitors, is under development; some members are already in clinical use (such as lepirudin, argatroban, bivalirudin and dabigatran). Also in clinical use are other small molecular compounds that interfere directly with the enzymatic action of particular coagulation factors (the directly acting oral anticoagulants: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban).[60]

History

[edit]Initial discoveries

[edit]Theories on the coagulation of blood have existed since antiquity. Physiologist Johannes Müller (1801–1858) described fibrin, the substance of a thrombus. Its soluble precursor, fibrinogen, was thus named by Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), and isolated chemically by Prosper Sylvain Denis (1799–1863). Alexander Schmidt suggested that the conversion from fibrinogen to fibrin is the result of an enzymatic process, and labeled the hypothetical enzyme "thrombin" and its precursor "prothrombin".[61][62] Arthus discovered in 1890 that calcium was essential in coagulation.[63][64] Platelets were identified in 1865, and their function was elucidated by Giulio Bizzozero in 1882.[65]

The theory that thrombin is generated by the presence of tissue factor was consolidated by Paul Morawitz in 1905.[66] At this stage, it was known that thrombokinase/thromboplastin (factor III) is released by damaged tissues, reacting with prothrombin (II), which, together with calcium (IV), forms thrombin, which converts fibrinogen into fibrin (I).[67]

Coagulation factors

[edit]The remainder of the biochemical factors in the process of coagulation were largely discovered in the 20th century.[citation needed]

A first clue as to the actual complexity of the system of coagulation was the discovery of proaccelerin (initially and later called Factor V) by Paul Owren (1905–1990) in 1947. He also postulated its function to be the generation of accelerin (Factor VI), which later turned out to be the activated form of V (or Va); hence, VI is not now in active use.[67]

Factor VII (also known as serum prothrombin conversion accelerator or proconvertin, precipitated by barium sulfate) was discovered in a young female patient in 1949 and 1951 by different groups.

Factor VIII turned out to be deficient in the clinically recognized but etiologically elusive hemophilia A; it was identified in the 1950s and is alternatively called antihemophilic globulin due to its capability to correct hemophilia A.[67]

Factor IX was discovered in 1952 in a young patient with hemophilia B named Stephen Christmas (1947–1993). His deficiency was described by Dr. Rosemary Biggs and Professor R.G. MacFarlane in Oxford, UK. The factor is, hence, called Christmas Factor. Christmas lived in Canada and campaigned for blood transfusion safety until succumbing to transfusion-related AIDS at age 46. An alternative name for the factor is plasma thromboplastin component, given by an independent group in California.[67]

Hageman factor, now known as factor XII, was identified in 1955 in an asymptomatic patient with a prolonged bleeding time named of John Hageman. Factor X, or Stuart-Prower factor, followed, in 1956. This protein was identified in a Ms. Audrey Prower of London, who had a lifelong bleeding tendency. In 1957, an American group identified the same factor in a Mr. Rufus Stuart. Factors XI and XIII were identified in 1953 and 1961, respectively.[67]

The view that the coagulation process is a "cascade" or "waterfall" was enunciated almost simultaneously by MacFarlane[68] in the UK and by Davie and Ratnoff[69] in the US, respectively.

Nomenclature

[edit]The usage of Roman numerals rather than eponyms or systematic names was agreed upon during annual conferences (starting in 1955) of hemostasis experts. In 1962, consensus was achieved on the numbering of factors I–XII.[70] This committee evolved into the present-day International Committee on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ICTH). Assignment of numerals ceased in 1963 after the naming of Factor XIII. The names Fletcher Factor and Fitzgerald Factor were given to further coagulation-related proteins, namely prekallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen, respectively.[67]

Factor VI[citation needed] is unassigned, as accelerin was found to be activated Factor V.

Other species

[edit]All mammals have an extremely closely related blood coagulation process[71], using a combined cellular and serine protease process.[citation needed] It is possible for any mammalian coagulation factor to "cleave" its equivalent target in any other mammal.[citation needed] The only non-mammalian animal known to use serine proteases for blood coagulation is the horseshoe crab.[72] Exemplifying the close links between coagulation and inflammation, the horseshoe crab has a primitive response to injury, carried out by cells known as amoebocytes (or hemocytes) which serve both hemostatic and immune functions.[40][73]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Furie, Barbara C.; Furie, Bruce (December 2005). "Thrombus formation in vivo". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (12): 3355–62. doi:10.1172/JCI26987. PMC 1297262. PMID 16322780.

- ^ Platelets. 2007. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-369367-9.X5760-7. ISBN 978-0-12-369367-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Coagulation Factor Tests". MedlinePlus Medical Test. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Schmaier, Alvin H.; Lazarus, Hillard M. (2011). Concise guide to hematology. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4051-9666-6. OCLC 779160978.

- ^ Lillicrap, D.; Key, Nigel; Makris, Michael; Denise, O'Shaughnessy (2009). Practical Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-4051-8460-1.

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (2023). "§18.5 Homeostasis". Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (2023). "§18.5 Homeostasis". Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ "Prothrombin thrombophilia". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ a b Waller, Derek G.; Sampson, Anthony P. (2018). "Haemostasis". Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. pp. 175–90. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-7167-6.00011-7. ISBN 978-0-7020-7167-6.

- ^ Blount, Zachary D. (25 March 2015). "The unexhausted potential of E. coli". eLife. 4 e05826. doi:10.7554/eLife.05826. PMC 4373459. PMID 25807083.

- ^ "Coagulation Cascade: What Is It, Steps, and More | Osmosis". www.osmosis.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "VWF gene: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 11 May 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Gordon, S. G.; Mielicki, W. P. (March 1997). "Cancer procoagulant: a factor X activator, tumor marker and growth factor from malignant tissue". Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 8 (2): 73–86. doi:10.1097/00001721-199703000-00001. ISSN 0957-5235. PMID 9518049.

- ^ Bloom, A. L. (1990). "Physiology of blood coagulation". Haemostasis. 20 (Suppl 1): 14–29. doi:10.1159/000216159. ISSN 0301-0147. PMID 2083865.

- ^ Abeles, Aryeh M.; Pillinger, Michael H.; Abramson, Steven B. (2015). "Inflammation and its mediators". Rheumatology. pp. 169–82. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-09138-1.00023-1. ISBN 978-0-323-09138-1.

- ^ Charo, I.F.; Bekeart, L.S.; Phillips, D.R. (July 1987). "Platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa-like proteins mediate endothelial cell attachment to adhesive proteins and the extracellular matrix". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (21): 9935–38. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61053-1. PMID 2440865.

- ^ Watson, Steve (April 2009). "Platelet Activation by Extracellular Matrix Proteins in Haemostasis and Thrombosis". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 15 (12): 1358–72. doi:10.2174/138161209787846702. PMID 19355974.

- ^ Wagner, D. D.; Urban-Pickering, M.; Marder, V. J. (January 1984). "Von Willebrand protein binds to extracellular matrices independently of collagen". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (2): 471–75. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81..471W. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.2.471. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 344699. PMID 6320190.

- ^ Vermylen, Jos; Verstraete, Marc; Fuster, Valentin (1 December 1986). "Role of platelet activation and fibrin formation in thrombogenesis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Symposium on Thrombosis and Antithrombotic Therapy – 1986. 8 (6, Supplement 2): 2B – 9B. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(86)80002-X. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 3537069. S2CID 23789418.

- ^ Blanchette, V. S.; Brandão, L. R.; Breakey, V. R.; Revel-Vilk, S. (2016). "Primary and secondary hemostasis, regulators of coagulation, and fibrinolysis: Understanding the basics". SickKids Handbook of Pediatric Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-3-318-03026-6.

- ^ "Coagulation Cascade: What Is It, Steps, and More". www.osmosis.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b Weisel, John W.; Litvinov, Rustem I. (2017). "Fibrin Formation, Structure and Properties". Fibrous Proteins: Structures and Mechanisms. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 82. pp. 405–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49674-0_13. ISBN 978-3-319-49672-6. ISSN 0306-0225. PMC 5536120. PMID 28101869.

- ^ LaPelusa, Andrew; Dave, Heeransh D. (2024). "Physiology, Hemostasis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31424847.

- ^ Loscalzo, J. (1995). "Endothelial injury, vasoconstriction, and its prevention". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 22 (2): 180–84. PMC 325239. PMID 7647603.

- ^ Yau, Jonathan W.; Teoh, Hwee; Verma, Subodh (19 October 2015). "Endothelial cell control of thrombosis". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 15 130. doi:10.1186/s12872-015-0124-z. ISSN 1471-2261. PMC 4617895. PMID 26481314.

- ^ Nigel Key; Michael Makris; et al. (2009). Practical Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-8460-1.

- ^ Watson, M. S.; Pallister, C. J. (2010). Haematology (2nd ed.). Scion Publishing. pp. 334–36. ISBN 978-1-904842-39-2. OCLC 1023165019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pallister CJ, Watson MS (2010). Haematology. Scion Publishing. pp. 336–47. ISBN 978-1-904842-39-2.

- ^ "Coagulation Factor". Clotbase.bicnirrh.res.in. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Hoffbrand, A. V.; Pettit, J. E; Moss, P. A. H. (2002). Essential Haematology (4th ed.). London: Blackwell Science. pp. 241–43. ISBN 978-0-632-05153-3. OCLC 898998816.

- ^ a b c Long AT, Kenne E, Jung R, Fuchs TA, Renné T (March 2016). "Contact system revisited: an interface between inflammation, coagulation, and innate immunity". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 14 (3): 427–37. doi:10.1111/jth.13235. PMID 26707513.

- ^ Ruff CT, Patel SM, Giugliano RP, Morrow DA, Hug B, Kuder JF, Goodrich EL, Chen SA, Goodman SG, Joung B, Kiss RG, Spinar J, Wojakowski W, Weitz JI, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Parkar S, Bloomfield D, Sabatine MS (January 2025). "Abelacimab versus Rivaroxaban in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 392 (4): 361–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2406674. PMID 39842011.

- ^ Troisi R, Balasco N, Autiero I, Sica F, Vitagliano L (August 2023). "New insight into the traditional model of the coagulation cascade and its regulation: illustrated review of a three-dimensional view". Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 7 (6) 102160. doi:10.1016/j.rpth.2023.102160. PMC 10506138. PMID 37727847.

- ^ Hoffman M (September 2003). "A cell-based model of coagulation and the role of factor VIIa". Blood Rev. 17 (Suppl 1): S1–5. doi:10.1016/s0268-960x(03)90000-2. PMID 14697207.

- ^ Moroi M, Induruwa I, Farndale RW, Jung SM (March 2022). "Factor XIII is a newly identified binding partner for platelet collagen receptor GPVI-dimer-An interaction that may modulate fibrin crosslinking". Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 6 (3) e12697. doi:10.1002/rth2.12697. PMC 9035508. PMID 35494504.

- ^ Hoffman MM, Monroe DM (September 2005). "Rethinking the coagulation cascade". Curr Hematol Rep. 4 (5): 391–96. PMID 16131441.

- ^ Hoffman, M. (August 2003). "Remodeling the blood coagulation cascade". Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 16 (1–2): 17–20. doi:10.1023/B:THRO.0000014588.95061.28. PMID 14760207. S2CID 19974377.

- ^ a b Hoffbrand, A.V. (2002). Essential haematology. Oxford: Blackwell Science. pp. 243–45. ISBN 978-0-632-05153-3.

- ^ Mayer, Gene (2011). "Ch. 1. Innate (non-specific) immunity". Immunology. Immunology Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line. University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ^ Peetermans M, Vanassche T, Liesenborghs L, Lijnen RH, Verhamme P (November 2016). "Bacterial pathogens activate plasminogen to breach tissue barriers and escape from innate immunity". Crit Rev Microbiol. 42 (6): 866–82. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2015.1080214. PMID 26485450.

- ^ a b Yong, J; Toh, CH (21 December 2023). "Rethinking coagulation: from enzymatic cascade and cell-based reactions to a convergent model involving innate immune activation". Blood. 142 (25): 2133–45. doi:10.1182/blood.2023021166. PMID 37890148.

- ^ Palta, A.; Palta, S.; Saroa, R. (2014). "Overview of the coagulation system". Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 58 (5): 515–23. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.144643. ISSN 0019-5049. PMC 4260295. PMID 25535411.

- ^ Signorelli, Salvatore Santo; Oliveri Conti, Gea; Fiore, Maria; Cangiano, Federica; Zuccarello, Pietro; Gaudio, Agostino; Ferrante, Margherita (26 November 2020). "Platelet-Derived Microparticles (MPs) and Thrombin Generation Velocity in Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Results of a Case–Control Study". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 16: 489–95. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S236286. ISSN 1176-6344. PMC 7705281. PMID 33273818.

- ^ Singh, S.; Dodt, J; Volkers, P.; Hethershaw, E.; Philippou, H.; Ivaskevicius, V.; Imhof, D.; Oldenburg, J.; Biswas, A. (5 August 2019). "Structure functional insights into calcium binding during the activation of coagulation factor XIII A". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 11324. Bibcode:2019NatSR...911324S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-47815-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6683118. PMID 31383913.

- ^ Paulus, MC; Drent, M; Kouw, IWK; Balvers, MGJ; Bast, A; van Zanten, ARH (1 July 2024). "Vitamin K: a potential missing link in critical illness-a scoping review". Critical Care. 28 (1): 212. doi:10.1186/s13054-024-05001-2. PMC 11218309. PMID 38956732.

- ^ a b c Dicks, AB; Moussallem, E; Stanbro, M; Walls, J; Gandhi, S; Gray, BH (9 January 2024). "A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors and Thrombophilia Evaluation in Venous Thromboembolism". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13 (2): 362. doi:10.3390/jcm13020362. PMC 10816375. PMID 38256496.

- ^ Maroney SA, Mast AE (June 2015). "New insights into the biology of tissue factor pathway inhibitor". J Thromb Haemost. 13 (Suppl 1): S200–07. doi:10.1111/jth.12897. PMC 4604745. PMID 26149025.

- ^ David Lillicrap; Nigel Key; Michael Makris; Denise O'Shaughnessy (2009). Practical Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 7–16. ISBN 978-1-4051-8460-1.

- ^ a b Stang, LJ; Mitchell, LG (2013). "Fibrinogen". Haemostasis. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 992. pp. 181–92. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-339-8_14. ISBN 978-1-62703-338-1. PMID 23546714.

- ^ Rasmussen KL, Philips M, Tripodi A, Goetze JP (June 2020). "Unexpected, isolated activated partial thromboplastin time prolongation: A practical mini-review". Eur J Haematol. 104 (6): 519–25. doi:10.1111/ejh.13394. PMID 32049377.

- ^ "Prothrombin Time Test and INR (PT/INR): MedlinePlus Medical Test". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Dorgalaleh A, Favaloro EJ, Bahraini M, Rad F (February 2021). "Standardization of Prothrombin Time/International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR)". Int J Lab Hematol. 43 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1111/ijlh.13349. PMID 32979036.

- ^ Hughes-Jones, N. C.; Wickramasinghe, S. N.; Hatton, Chris (2008). Haematology (8th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell Publishers. pp. 145–66. ISBN 978-1-4051-8050-4. OCLC 1058077604.

- ^ "Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Andreescu M, Andreescu B (March 2024). "A Review About the Assessment of the Bleeding and Thrombosis Risk for Patients With Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Scheduled for Surgery". Cureus. 16 (3) e56008. doi:10.7759/cureus.56008. PMC 11007487. PMID 38606222.

- ^ Demoy M, Labrousse J, Grand F, Moyrand S, Tuffigo M, Lamarche S, Macchi L (June 2024). "[Factor XI deficiency: actuality and review of the literature]". Annales de Biologie Clinique (in French). 82 (2): 225–36. doi:10.1684/abc.2024.1884. PMID 38702892.

- ^ Huber J, Stanworth SJ, Doree C, Fortin PM, Trivella M, Brunskill SJ, et al. (November 2019). Cochrane Haematology Group (ed.). "Prophylactic plasma transfusion for patients without inherited bleeding disorders or anticoagulant use undergoing non-cardiac surgery or invasive procedures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11) CD012745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012745.pub2. PMC 6993082. PMID 31778223.

- ^ Middeldorp S, Nieuwlaat R, Baumann Kreuziger L, Coppens M, Houghton D, James AH, Lang E, Moll S, Myers T, Bhatt M, Chai-Adisaksopha C, Colunga-Lozano LE, Karam SG, Zhang Y, Wiercioch W, Schünemann HJ, Iorio A (November 2023). "American Society of Hematology 2023 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: thrombophilia testing". Blood Adv. 7 (22): 7101–38. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010177. PMC 10709681. PMID 37195076.

- ^ Kaufmann, J.E.; Vischer, U.M. (April 2003). "Cellular mechanisms of the hemostatic effects of desmopressin (DDAVP)". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1 (4): 682–89. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00190.x. PMID 12871401.

- ^ Crader, Marsha F.; Johns, Tracy; Arnold, Justin K. (2025), "Warfarin Drug Interactions", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28722993, retrieved 24 July 2025

- ^ Soff GA (March 2012). "A new generation of oral direct anticoagulants". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 32 (3): 569–74. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242834. PMID 22345595.

- ^ Schmidt A (1872). "Neue Untersuchungen über die Faserstoffgerinnung". Pflügers Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie. 6: 413–538. doi:10.1007/BF01612263. S2CID 37273997.

- ^ Schmidt A. Zur Blutlehre. Leipzig: Vogel, 1892.

- ^ Arthus M, Pagès C (1890). "Nouvelle theorie chimique de la coagulation du sang". Arch Physiol Norm Pathol. 5: 739–46.

- ^ Shapiro SS (October 2003). "Treating thrombosis in the 21st century". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (18): 1762–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMe038152. PMID 14585945.

- ^ Brewer DB (May 2006). "Max Schultze (1865), G. Bizzozero (1882) and the discovery of the platelet". British Journal of Haematology. 133 (3): 251–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06036.x. PMID 16643426.

- ^ Morawitz P (1905). "Die Chemie der Blutgerinnung". Ergebn Physiol. 4: 307–422. doi:10.1007/BF02321003. S2CID 84003009.

- ^ a b c d e f Giangrande PL (June 2003). "Six characters in search of an author: the history of the nomenclature of coagulation factors". British Journal of Haematology. 121 (5): 703–12. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04333.x. PMID 12780784. S2CID 22694905.

- ^ Macfarlane RG (May 1964). "An enzyme cascade in the blood clotting mechanism, and its function as a biochemical amplifier". Nature. 202 (4931): 498–99. Bibcode:1964Natur.202..498M. doi:10.1038/202498a0. PMID 14167839. S2CID 4214940.

- ^ Davie EW, Ratnoff OD (September 1964). "Waterfall sequence for intrinsic blood clotting". Science. 145 (3638): 1310–12. Bibcode:1964Sci...145.1310D. doi:10.1126/science.145.3638.1310. PMID 14173416. S2CID 34111840.

- ^ Wright IS (February 1962). "The nomenclature of blood clotting factors". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 86 (8): 373–74. PMC 1848865. PMID 14008442.

- ^ Staelens, Louis; Langenaeken, Tom; Rega, Filip; Meuris, Bart (1 March 2025). "Difference in coagulation systems of large animal species used in cardiovascular research: a systematic review". Journal of Artificial Organs. 28 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10047-024-01446-y. ISSN 1619-0904. PMC 11832548. PMID 38769278.

- ^ Osaki T, Kawabata S (June 2004). "Structure and function of coagulogen, a clottable protein in horseshoe crabs". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (11): 1257–65. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-3396-5. PMC 11138774. PMID 15170505. S2CID 24537601.

- ^ Iwanaga, S (May 2007). "Biochemical principle of Limulus test for detecting bacterial endotoxins". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 83 (4): 110–19. Bibcode:2007PJAB...83..110I. doi:10.2183/pjab.83.110. PMC 3756735. PMID 24019589.

Further reading

[edit]- Hoffman, Maureane; Monroe, Dougald (2001). "A Cell-based Model of Hemostasis". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 85 (6): 958–65. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1615947. PMID 11434702.

- Hoffman M, Monroe DM (February 2007). "Coagulation 2006: a modern view of hemostasis". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2006.11.004. PMID 17258114.

External links

[edit] Media related to Coagulation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coagulation at Wikimedia Commons

Coagulation

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Process

Coagulation is the physiological process by which blood transforms from a liquid state to a gel-like form, resulting in the formation of a clot that seals damaged blood vessels and prevents excessive blood loss.[2] This process is a critical component of hemostasis, the body's overall mechanism to arrest bleeding following vascular injury while preserving blood flow through undamaged vessels to maintain vascular patency.[4] Hemostasis encompasses several sequential stages that collectively achieve clot formation. Initial vasoconstriction immediately narrows the injured vessel (within seconds to minutes) to reduce immediate blood flow and loss.[5] This is followed by primary hemostasis, where platelets adhere to the exposed subendothelial matrix and aggregate to form a temporary platelet plug.[4] Secondary hemostasis then activates the coagulation cascade, involving enzymatic reactions that generate fibrin strands to reinforce the plug into a stable clot.[1] Finally, clot stabilization occurs through cross-linking of fibrin, ensuring durability until tissue repair is complete.[2] The timeline of clot formation is rapid to minimize hemorrhage risk, beginning with vasoconstriction within seconds to minutes of injury and progressing to platelet plug formation in under a minute, while fibrin mesh development typically completes within 2 to 7 minutes.[4] This orchestrated sequence not only halts bleeding efficiently but also balances clot formation to avoid occlusion of healthy vasculature, thereby supporting ongoing circulation and preventing ischemic complications.[2]Importance in Hemostasis

Hemostasis represents a coordinated physiological response that integrates vascular, platelet, and plasma components to preserve blood fluidity within intact vessels while rapidly sealing breaches to prevent excessive blood loss.[6] This multifaceted process begins with vasoconstriction to minimize initial hemorrhage, followed by platelet adhesion and aggregation to form a primary plug, and culminates in plasma-mediated coagulation to stabilize the clot through fibrin formation.[2] By balancing these elements, hemostasis ensures vascular integrity without compromising circulation, adapting dynamically to the scale of injury.[6] Impaired coagulation disrupts this equilibrium, leading to either uncontrolled hemorrhage from inadequate clot formation or pathological thrombosis from excessive clotting.[2] Deficiencies in coagulation factors can result in prolonged bleeding after minor trauma, as seen in conditions where the plasma phase fails to reinforce the platelet plug.[2] Conversely, hyperactive coagulation promotes unwanted thrombus formation in undamaged vessels, increasing risks of vascular occlusion and tissue ischemia.[2] These outcomes underscore coagulation's pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis, where even subtle imbalances can threaten survival.[6] From an evolutionary perspective, coagulation emerged as an adaptive mechanism over 450 million years ago in jawless vertebrates, enabling survival in environments prone to physical injury and infection.[7] This system evolved to not only stanch blood loss but also to provide a defensive barrier against pathogens, reflecting the selective pressures of terrestrial and predatory lifestyles.[8] The conservation of core coagulation elements across species highlights its fundamental importance for organismal resilience.[7] Coagulation further integrates with innate immune responses, where fibrin clots serve to physically contain pathogens at injury sites, limiting their dissemination and facilitating immune clearance.[9] Activated coagulation factors, such as thrombin, recruit immune cells and enhance antimicrobial defenses, illustrating a synergistic interplay that bolsters host protection during infection.[9] This linkage evolved to coordinate wound repair with pathogen control, optimizing survival outcomes.[8]Coagulation Factors

List and Functions

Coagulation factors comprise a series of plasma proteins and cofactors critical to the hemostatic process, designated by Roman numerals from I to XIII, with additional contact phase components including high-molecular-weight kininogen (HMWK), prekallikrein (PK), and von Willebrand factor (vWF). These factors exist predominantly as inactive precursors (zymogens) that undergo proteolytic activation to perform enzymatic, cofactor, or structural roles in clot formation. The following details their individual biochemical functions and activation states.[10]| Factor | Alternative Name | Biochemical Role | Activation State |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Fibrinogen | Soluble plasma glycoprotein that serves as the precursor to fibrin, providing the structural framework for clot formation through polymerization into insoluble strands. | Zymogen form is fibrinogen; activated by thrombin cleavage to fibrin monomers that spontaneously polymerize.[10] |

| II | Prothrombin | Vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein acting as the precursor to the central enzyme thrombin, which cleaves fibrinogen and activates other factors. | Zymogen form is prothrombin; activated by Factor Xa cleavage to thrombin (IIa).[10] |

| III | Tissue Factor | Integral membrane glycoprotein that functions as a cofactor to enhance the activity of Factor VIIa. | Not a zymogen; constitutively expressed on cell surfaces and becomes functional upon exposure to blood.[10] |

| IV | Calcium Ions | Divalent cation that facilitates the binding of vitamin K-dependent factors to phospholipid surfaces and stabilizes protein complexes. | Not a protein zymogen; present in ionized form in plasma to support conformational changes in other factors.[10] |

| V | Proaccelerin or Labile Factor | Non-enzymatic cofactor that dramatically amplifies the proteolytic activity of Factor Xa toward prothrombin. | Inactive zymogen form; activated by limited proteolysis to Factor Va.[10] |

| VI | (Obsolete; refers to activated Factor V) | No distinct role; historically denoted activated V but not recognized as a separate entity. | N/A.[10] |

| VII | Proconvertin or Stable Factor | Vitamin K-dependent serine protease zymogen that, when activated, cleaves Factor X to initiate downstream events. | Inactive zymogen; activated to VIIa by trace amounts of other proteases.[10] |

| VIII | Antihemophilic Factor | Plasma glycoprotein cofactor that enhances the activity of Factor IXa in the activation of Factor X; circulates bound to vWF. | Inactive precursor; activated to VIIIa by thrombin or Factor Xa.[10] |

| IX | Christmas Factor or Plasma Thromboplastin Component | Vitamin K-dependent serine protease that activates Factor X when complexed with Factor VIIIa on phospholipid surfaces. | Zymogen form; activated to IXa by Factor XIa or VIIa-tissue factor.[10] |

| X | Stuart-Prower Factor | Vitamin K-dependent serine protease central to both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, cleaving prothrombin to thrombin. | Zymogen; activated to Xa by Factor IXa or VIIa-tissue factor complexes.[10] |

| XI | Plasma Thromboplastin Antecedent | Serine protease zymogen that activates Factor IX; functions in the contact activation phase. | Inactive zymogen; activated to XIa by Factor XIIa or thrombin.[10] |

| XII | Hageman Factor | Serine protease zymogen involved in contact activation, converting prekallikrein to kallikrein and autoamplifying its own activation. | Inactive zymogen; activated to XIIa upon contact with negatively charged surfaces.[10] |

| XIII | Fibrin-Stabilizing Factor | Transglutaminase enzyme that cross-links fibrin chains and incorporates other proteins like alpha-2-antiplasmin into the clot for mechanical stability. | Inactive zymogen (heterotetramer of A and B subunits); activated to XIIIa by thrombin in the presence of calcium.[10] |