Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

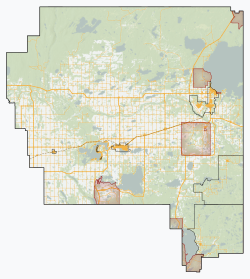

Cold Lake, Alberta

View on Wikipedia

Cold Lake is a city in north-east Alberta, Canada and is named after the lake nearby. Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake (CFB Cold Lake) is situated within the city's outer limits.

Key Information

History

[edit]Cold Lake was first recorded on a 1790 map, by the name of Coldwater Lake.[6] Originally three communities, Cold Lake was formed by merging the Town of Grand Centre, the Town of Cold Lake, and Medley (CFB Cold Lake) on October 1, 1996. Grand Centre was renamed Cold Lake South, and the original Cold Lake is known as Cold Lake North. Because of its origins, the area is also known as the Tri-Town.

Fossil record

[edit]Cold Lake preserves an extensive fossil and subfossil record from the Pleistocene after the Last Glacial Maximum to the Late Holocene. By the Middle Holocene, the mammalian biota in the region was essentially modern.[7]

Geography

[edit]The city is situated in Alberta's "Lakeland" district, 300 km (190 mi) northeast of Edmonton, near the Alberta-Saskatchewan provincial border. The area surrounding the city is sparsely populated, and consists mostly of farmland.

Climate

[edit]Cold Lake's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb). Summers are generally warm with cool nights, and winters are very cold with moderate snowfall.

The record high temperature was 36.3 °C (97.3 °F) recorded June 27, 2002.[8] The record high daily minimum was 23.1 °C (73.6 °F) recorded July 2, 2021.[8] The record highest dew point was 23.9 °C (75.0 °F) recorded July 18, 1955.[8] The most humid month was July 2024 with an average dew point of 13.7 °C (56.7 °F).[8] The warmest month was July 2007 with an average mean tempeature of 20.9 °C (69.6 °F).[8]

| Climate data for Cold Lake Regional Airport, Alberta (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1952–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 10.6 | 12.1 | 17.1 | 28.7 | 33.8 | 38.0 | 43.2 | 39.0 | 34.0 | 27.7 | 18.3 | 10.0 | 43.2 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

36.3 (97.3) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

31.9 (89.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −9.9 (14.2) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

0.5 (32.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

8.4 (47.1) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −19.6 (−3.3) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −35.2 (−31.4) |

−30.8 (−23.4) |

−26.8 (−16.2) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−37.7 (−35.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −48.3 (−54.9) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

−41.1 (−42.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−36.7 (−34.1) |

−44.4 (−47.9) |

−48.3 (−54.9) |

| Record low wind chill | −53.3 | −55.4 | −49.3 | −37.2 | −14.7 | −6.7 | 0.0 | −6.0 | −14.9 | −29.0 | −48.5 | −52.6 | −55.4 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.4 (0.69) |

12.6 (0.50) |

17.8 (0.70) |

33.9 (1.33) |

39.9 (1.57) |

85.5 (3.37) |

79.4 (3.13) |

52.3 (2.06) |

38.8 (1.53) |

23.7 (0.93) |

19.2 (0.76) |

16.0 (0.63) |

436.5 (17.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.7 (0.03) |

0.2 (0.01) |

2.6 (0.10) |

20.1 (0.79) |

38.1 (1.50) |

85.4 (3.36) |

79.4 (3.13) |

52.1 (2.05) |

38.6 (1.52) |

15.1 (0.59) |

1.6 (0.06) |

0.4 (0.02) |

334.3 (13.16) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 23.4 (9.2) |

16.5 (6.5) |

18.0 (7.1) |

14.3 (5.6) |

2.0 (0.8) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.1) |

7.8 (3.1) |

22.6 (8.9) |

21.9 (8.6) |

127 (49.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 10.5 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 13.2 | 14.0 | 11.9 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 120.2 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.9 | 0.23 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 9.0 | 13.2 | 14.0 | 11.9 | 10.0 | 6.2 | 1.3 | 0.47 | 73.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 10.7 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 4.2 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 55.19 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.8 | 62.0 | 53.8 | 45.7 | 40.4 | 49.5 | 51.6 | 50.7 | 51.1 | 55.9 | 69.8 | 73.4 | 56.1 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −18.2 (−0.8) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 87.1 | 118.2 | 172.3 | 221.6 | 260.0 | 265.2 | 283.0 | 279.9 | 176.9 | 140.9 | 82.2 | 68.3 | 2,155.5 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 35.4 | 43.1 | 47.0 | 52.6 | 52.3 | 51.6 | 54.9 | 60.6 | 46.2 | 43.1 | 32.1 | 29.7 | 45.7 |

| Source 1: Environment Canada[9][10] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: weatherstats.ca (for dewpoint and monthly&yearly average absolute maximum&minimum temperature)[8] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 11,791 | — |

| 2001 | 11,520 | −2.3% |

| 2006 | 11,991 | +4.1% |

| 2011 | 13,839 | +15.4% |

| 2016 | 14,961 | +8.1% |

| 2021 | 15,661 | +4.7% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [11][12][13][14][3] Note: The 1996 population is the adjusted population of the amalgamated City of Cold Lake formed on October 1, 1996. | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 302 | — |

| 1951 | 414 | +37.1% |

| 1956 | 1,097 | +165.0% |

| 1961 | 1,307 | +19.1% |

| 1966 | 1,289 | −1.4% |

| 1971 | 1,309 | +1.6% |

| 1976 | 1,317 | +0.6% |

| 1981 | 2,110 | +60.2% |

| 1986 | 3,195 | +51.4% |

| 1991 | 3,878 | +21.4% |

| 1996 | 4,089 | +5.4% |

| 2001 | 4,676 | +14.4% |

| 2006 | 5,560 | +18.9% |

| 2011 | 6,455 | +16.1% |

| 2016 | 7,121 | +10.3% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Note: The 2001 population is of the former Town of Cold Lake that amalgamated with the Town of Grand Centre and Medley (CFB 4 Wing) on October 1, 1996. | ||

The population of the City of Cold Lake according to its 2022 municipal census is 16,302,[5] a change of 3.6% from its 2014 municipal census population of 15.736.[27]

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Cold Lake had a population of 15,661 living in 6,114 of its 6,767 total private dwellings, a change of 4.6% from its 2016 population of 14,976. With a land area of 66.61 km2 (25.72 sq mi), it had a population density of 235.1/km2 (608.9/sq mi) in 2021.[3]

In the Canada 2016 census conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Cold Lake had a population of 14,961 living in 5,597 of its 6,657 total private dwellings, a change of 8.1% from its 2011 population of 13,839. With a land area of 59.92 km2 (23.14 sq mi), it had a population density of 249.7/km2 (646.7/sq mi) in 2016.[14]

Ethnicity

[edit]About 8.7% of residents identified themselves as aboriginal at the time of the 2006 census.[28]

| Panethnic group | 2021[29] | 2016[30] | 2011[31] | 2006[32] | 2001[33] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[a] | 11,475 | 74.78% | 11,665 | 79.76% | 11,710 | 84.95% | 10,575 | 88.46% | 10,320 | 90.13% |

| Indigenous | 2,330 | 15.18% | 1,360 | 9.3% | 1,330 | 9.65% | 1,035 | 8.66% | 850 | 7.42% |

| Southeast Asian[b] | 760 | 4.95% | 625 | 4.27% | 195 | 1.41% | 30 | 0.25% | 25 | 0.22% |

| South Asian | 230 | 1.5% | 185 | 1.26% | 110 | 0.8% | 55 | 0.46% | 60 | 0.52% |

| African | 205 | 1.34% | 250 | 1.71% | 120 | 0.87% | 75 | 0.63% | 50 | 0.44% |

| Middle Eastern[c] | 105 | 0.68% | 90 | 0.62% | 80 | 0.58% | 70 | 0.59% | 10 | 0.09% |

| Latin American | 90 | 0.59% | 100 | 0.68% | 85 | 0.62% | 10 | 0.08% | 0 | 0% |

| East Asian[d] | 85 | 0.55% | 255 | 1.74% | 70 | 0.51% | 85 | 0.71% | 135 | 1.18% |

| Other/multiracial[e] | 60 | 0.39% | 110 | 0.75% | 80 | 0.58% | 40 | 0.33% | 0 | 0% |

| Total responses | 15,345 | 97.98% | 14,625 | 97.66% | 13,785 | 99.61% | 11,955 | 99.7% | 11,450 | 99.39% |

| Total population | 15,661 | 100% | 14,976 | 100% | 13,839 | 100% | 11,991 | 100% | 11,520 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Language

[edit]Almost 89% of residents identified English and more than 7% identified French as their first language. Almost 1% identified German, 0.5% identified Chinese, 0.4% each identified Dutch and Ukrainian, and 0.3% each identified Cree and Arabic as their first language learned.[34]

Religion

[edit]About 82 percent of residents identified as Christian at the time of the 2001 census, while more than 17 percent indicated they had no religious affiliation. For specific denominations Statistics Canada found that 40% of residents identified as Roman Catholic, 14% identified with the United Church of Canada, 5.5% identified as Anglican, 3% as Baptist, 2.5% as Lutheran, and 2% as Pentecostal.[35]

Economy

[edit]The city's economy is inextricably linked to military spending at CFB Cold Lake. The region also supports oil and gas exploration and production. The Athabasca Oil Sands project in Fort McMurray is having a growing influence in the region as well. The Cold Lake oil sands may become a significant contributor to the local economy.

A job market analysis from December 2024 to January 2025 showed that the Oil & Gas sector accounted for 33% of job postings in the region, with administrative roles and skilled trades also in high demand.[36]

Every year Cold Lake hosts military forces from around the world for Exercise Maple Flag, a training exercise where pilots and support staff of NATO allies can take advantage of the Air Weapons Range and relatively open rural air space. Running from 4 to 6 weeks and starting in May of each year, commercial accommodations in the entire region are left with little to no vacancy. This annual exercise contributes a substantial amount of capital into these industries and other hospitality-related businesses.

In popular culture

[edit]Sports

[edit]

Cold Lake has a variety of sports, including:

- Hockey (Home to the Cold Lake Ice, Junior B Team) & (Home to the Cold Lake Freeze, Minor Hockey Teams)

- Lacrosse (Home to the Cold Lake Heat, Minor Lacrosse Teams)[38]

- Volleyball (Assumption and CLHS Royals)

- Football (CLHS Royals)

- Basketball (Assumption and CLHS Royals)

- Soccer (Indoor and outdoor-Cold Lake Minor Soccer[39])

- Baseball

- Rugby (Assumption Crusader's and CLHS Royals combined team and Cold Lake Penguins Men's RFC)

- Hapkido

- Tae Kwon Do (Hetlinger taekwondo, and occasionally International Taekwon-Do Federation or World Taekwondo Federation)

- Figure Skating (Cold Lake Figure Skating Club)[40]

- Figure Skating (Norlight Skating Club)

- Downhill Skiing (Kinosoo Ridge Snow Resort)[41]

- Dancing (Pirouette School of Dance with award-winning dance team, Fame Dance (Located at the Energy Centre)[42]

- Mixed Martial Arts (Team Sparta)

- Roller Derby (Lakeland Ladykillers Roller Derby League)

- Swimming (Cold Lake Marlins Swim Club)[43]

- Powerlifting (Cold Lake Bar Benders)

- Gymnastics (Lakeland Gymnastics Club)

- Disc Golf

- Pickleball

- Bowling (Marina Bowling Centre)

Government

[edit]Mayors:

- Craig Copeland, 2007–present

- Allan Buck, 2004–2007

- Hansa Thaleshvar, 1998–2004

- Raymond Coates, 1996–1998

The last local election was held in October 2021. As of 2021, the councillors of Cold Lake are Bob Mattice, Chris Vining, Vicky Lefebvre, Adele Richardson, Ryan Bailey, and Bill Parker.

At the provincial level, the city is in the district of Bonnyville-Cold Lake-St. Paul. Its current representative is Scott Cyr, from the United Conservative Party.

At the federal level, the city is in the district of Fort McMurray—Cold Lake. Its current representative is Laila Goodridge, from the Conservative Party of Canada.

Education

[edit]Portage College operates a campus at Cold Lake. Program offerings include academic upgrading, accounting, community social works, nursing, power engineering and university studies among others.[44]

Lakeland Catholic School District No. 150 and Northern Lights School Division No. 69 operate public schools within Cold Lake.[45][46] Cold Lake also hosts a Francophone school named École Voyageur that offers French programming for kindergarten through grade 12,[47][48] as well as the Cold Lake Cadet Summer Training Centre.

- Lakeland Catholic School District No. 150

- Holy Cross Elementary School (offering kindergarten through grade 6 programming)[49]

- École St. Dominic School (offering pre-kindergarten through grade 6 English and French programming)[50]

- Assumption Junior/Senior High School (offering grade 7 through grade 12 English and French programming)[51]

- Northern Lights School Division No. 69

- Cold Lake Elementary School (offering pre-kindergarten through grade 3 programming)[52]

- Ecole North Star Elementary School (offering kindergarten through grade 3 English and French programming)[53]

- Nelson Heights School (offering grade 4 through grade 6 programming)[54]

- Cold Lake Junior High (offering grade 7 through grade 9)[55]

- Cold Lake High School (offering grade 10 through grade 12 programming)[56]

- Bridges Outreach School (offering grade 8 and grade 9 programming)[57]

- Cold Lake Outreach School (offering grade 10 through grade 12 programming)[58]

Recreation

[edit]Cold Lake is situated near many campgrounds due to its proximity to the lake. The M.D. campground has powered sites, shower facilities with flush toilets, and a covered camp picnic area. The Cold Lake Provincial Park has many sites, and is more secluded than the M.D. site (which is surrounded by development). The Provincial campground boasts a wilderness trail system, a beach, boat launch and a powered section. Nearby Meadow Lake Provincial Park to the east, across the border in Saskatchewan, has facilities similar to Cold Lake Provincial Park.

Kinosoo Beach is a favorite destination during the hot summer months between June and August.

The Iron Horse Trail, a recreational trail situated on a former railway line (see rail trail) has its easternmost terminus in Cold Lake.

Recreational pastimes include, among others:

Museums

[edit]Air Force Museum

[edit]

The Air Force Museum preserves and exhibits the history of CFB Cold Lake and of 42 Radar Squadron. 42 Radar was on this site from 1954 to 1992, so Cold War era technology is mostly on display in their exhibit. An example of this is the General Electric Height Finder Radar on display.

The Museum has much 4 Wing history on display. The current 4 Wing standing squadrons such as 409 Squadron, 410 Squadron, 419 Squadron, 1 Air Maintenance Squadron, Aerospace Engineering Test Establishment and others are displayed in the Museum. There are a few exhibits of purely historic nature, such as displays on 441 and 416, Squadrons which stood down in 2006 to be amalgamated into 409 Squadron.

The Museum also has four aircraft on display outside, including the CF-5 Freedom Fighter, CT-133 Silver Star, the CT-114 Tutor and the CT-134 Musketeer. The newest addition to the air park is a CF-188 Decoy.[63]

Oil and Gas Museum

[edit]This exhibit was designed, researched and constructed by Grand Centre High School students. This museum explains the history of Oil and gas in the Cold Lake area from Paleolithic times to the present.

Heritage Museum

[edit]The Heritage Museum exhibits a time line of life in Cold Lake, both domestic and commercial. The museum also boasts some impressive murals.

Aboriginal Museum

[edit]The Aboriginal Museum displays the history of the Dene, Cree and Metis peoples in time lines, maps, crafts and cultural displays. There are also bears on display.

Notable people

[edit]- Alex Auld, NHL goaltender

- Garry Howatt, NHL forward

- Alex Janvier, artist

- Bonnie McFarlane, comedian

- René Richard, artist[64]

- Curtis Hargrove, charity runner

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Location and History Profile: City of Cold Lake" (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. June 17, 2016. p. 36. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Municipal Officials Search". Alberta Municipal Affairs. May 9, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities)". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Alberta Private Sewage Systems 2009 Standard of Practice Handbook: Appendix A.3 Alberta Design Data (A.3.A. Alberta Climate Design Data by Town)" (PDF) (PDF). Safety Codes Council. January 2012. pp. 212–215 (PDF pages 226–229). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "City of Cold Lake Municipal Census 2022 Report" (PDF). City of Cold Lake. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Harry (2003). The Story Behind Alberta Names How Cities, Towns, Villages and Hamlets Got their Names. Red Deer Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-88995-256-0.

- ^ Jass, Christopher N.; Caldwell, Devyn; Barrón-Ortiz, Christina I.; Beaudoin, Alwynne B.; Brink, Jack; Sawchuk, Matthew (29 November 2017). "Underwater faunal assemblages: radiocarbon dates and late Quaternary vertebrates from Cold Lake, Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 55 (3): 283–294. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0131. hdl:1807/82470. ISSN 0008-4077. Retrieved 13 August 2024 – via Canadian Science Publishing.

- ^ a b c d e f "Cold Lake". List of charts for Cold Lake. weatherstats.ca. February 6, 2026. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1991–2020". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Population and Dwelling Counts, for Canada, Provinces and Territories, and Census Divisions, 2001 and 1996 Censuses - 100% Data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. 2010-01-06. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses". Statistics Canada. 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Ninth Census of Canada, 1951. Vol. SP-7, Population: Unincorporated villages and hamlets. Dominion Bureau of Statistics. pp. 55–57.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by sex, for census subdivisions, 1956 and 1951". Census of Canada, 1956. Vol. Population, Counties and Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1957. p. 6.50–6.53.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1901–1961". 1961 Census of Canada. Series 1.1: Historical, 1901–1961. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1963. p. 6.77-6.83.

- ^ "Population by specified age groups and sex, for census subdivisions, 1966". Census of Canada, 1966. Vol. Population, Specified Age Groups and Sex for Counties and Census Subdivisions, 1966. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1968. p. 6.50–6.53.

- ^ "Table 2: Population of Census Subdivisions, 1921–1971". 1971 Census of Canada. Vol. I: Population, Census Subdivisions (Historical). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1973. p. 2.102-2.111.

- ^ "Table 3: Population for census divisions and subdivisions, 1971 and 1976". 1976 Census of Canada. Census Divisions and Subdivisions, Western Provinces and the Territories. Vol. I: Population, Geographic Distributions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1977. p. 3.40–3.43.

- ^ "Table 4: Population and Total Occupied Dwellings, for Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 1976 and 1981". 1981 Census of Canada. Vol. II: Provincial series, Population, Geographic distributions (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1982. p. 4.1–4.10. ISBN 0-660-51095-2.

- ^ "Table 2: Census Divisions and Subdivisions – Population and Occupied Private Dwellings, 1981 and 1986". Census Canada 1986. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Provinces and Territories (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1987. p. 2.1–2.10. ISBN 0-660-53463-0.

- ^ "Table 2: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 1986 and 1991 – 100% Data". 91 Census. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1992. pp. 100–108. ISBN 0-660-57115-3.

- ^ "Table 10: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions, Census Subdivisions (Municipalities) and Designated Places, 1991 and 1996 Censuses – 100% Data". 96 Census. Vol. A National Overview – Population and Dwelling Counts. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1997. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0-660-59283-5.

- ^ "2001 Community Profiles – Cold Lake, Alberta (Town / Dissolved)". Statistics Canada. 2007-02-01. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- ^ "2017 Growth Study Addendum". City of Cold Lake. February 2018. p. 368. Retrieved October 21, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Census shows more than 9 per cent growth over two years". City of Cold Lake. July 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Cold Lake". Aboriginal Identity (8), Sex (3) and Age Groups (12) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data. Statistics Canada. 2008-01-15. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-10-26). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2021-10-27). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2015-11-27). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-08-20). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-07-02). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ "Cold Lake". Detailed Mother Tongue (186), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 and 2006 Censuses - 20% Sample Data. Statistics Canada. 2007-11-20. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ "Cold Lake". Religion (95A), Age Groups (7A) and Sex (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 1991 and 2001 Censuses - 20% Sample Data. Statistics Canada. 2007-03-01. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Cold Lake & Bonnyville Jobs: Job Market Trends & Opportunities in 2024-2025

- ^ Brisebois, Dan (July 27, 2020). "Celebrating a super hero's roots". Cold Lake Sun. Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ Lakeland Lacrosse Lakeland Lacrosse

- ^ Jesse Nesvold (2017-02-25). "CLMSA". CLMSA. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ "Cold Lake Figure Skating Club (CLFSC)". Cold Lake Figure Skating Club.

- ^ a b Kinosoo Ridge Snow Resort Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pirouette School of Dance". Pirouette School of Dance. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "502 Bad Gateway". www.marlinsswim.com.

- ^ "Cold Lake Campus". Portage College. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ "Lakeland Catholic Schools". Lakeland Catholic School District. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Welcome". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "CFMWS Cold Lake Schools". Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services. Retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ "École Voyageur". Conseil scolaire Centre-Est. Retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ "Holy Cross Elementary". Lakeland Catholic School District. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "St. Dominic Elementary School". Lakeland Catholic School District. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Assumption Jr/Sr High School". Lakeland Catholic School District. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Cold Lake Elementary: Staff Directory". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Ecole North Star Elementary School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Nelson Heights School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Cold Lake Middle School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Cold Lake High School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Bridges Outreach School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Archived from the original on 2015-06-04. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Cold Lake Outreach School: Programs". Northern Lights School Division No. 69. Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ "Home". Cold Lake Minor Hockey Association. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ "Lakeland Lacrosse Association : Website by RAMP InterActive". www.lakelandlacrosse.ca.

- ^ "Cold Lake Sailing Club". Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ "Lakeland Ladykillers Roller Derby League". Lakeland Ladykillers Roller Derby League.

- ^ James Knaus Curator Cold Lake Air force Museum

- ^ "René Richard: Cold Laker, Québécois, and the Tom Thomson of the North – Respect". Retrieved 2023-03-22.

External links

[edit]Cold Lake, Alberta

View on GrokipediaHistory

Indigenous Presence and Early Settlement

The region surrounding Cold Lake was traditionally occupied by Cree and Dene (Chipewyan) peoples, who relied on the lake and adjacent boreal forests for subsistence through fishing, hunting large game such as moose and caribou, and trapping furbearers.[5] [6] These groups maintained trade networks, with Cree exchanging furs, fish, and other goods with Dene communities in northern Alberta, facilitating economic interdependence prior to intensive European involvement.[7] Dene oral histories trace continuous habitation in the area to times predating written records, emphasizing practical adaptation to the landscape's resources amid seasonal migrations.[5] In 1876, ancestors of the Cold Lake First Nations adhered to Treaty 6, negotiated between the Canadian Crown and various Cree, Dene, and Nakota bands amid declining bison herds and uncertainties over land use following the Hudson's Bay Company's sale of Rupert's Land.[5] [8] The treaty formalized reserve allocations, with Cold Lake bands selecting tracts for exclusive use, alongside assurances of rights to hunt, trap, and fish on unoccupied Crown lands, supplemented by provisions like annuities, ammunition, and agricultural tools to support transition to farming during resource scarcities.[5] [9] These terms reflected pragmatic exchanges, as Indigenous leaders sought security against famine and encroachment while ceding broader territorial claims.[8] European fur trade activities reached Cold Lake in the late 19th century, with a Hudson's Bay Company post established around 1877 to procure furs from local Indigenous trappers, continuing operations until 1938 amid declining beaver populations from overharvesting.[10] This outpost facilitated commodity exchanges, including European goods for pelts, integrating the area into broader North Saskatchewan River trade routes. Permanent non-Indigenous settlement emerged in the early 20th century through homesteading, as families like the McNeills claimed land for mixed farming and subsistence activities, drawn by government incentives under the Dominion Lands Act to cultivate marginal boreal soils despite challenges like short growing seasons.[11] [12] These efforts prioritized economic viability, with initial settlers combining agriculture, trapping, and fishing to offset the fur trade's contraction.[12]European Exploration and Development

European fur traders from the North West Company established a post at Cold Lake in the early 19th century, focusing on exchanges of furs for European goods and provisions with local Indigenous groups.[13] After the 1821 merger with the Hudson's Bay Company, operations continued as an outpost linked to Onion Lake, with records documenting activity from the 1890s through 1932 to support regional trade networks.[10] These posts, including one near the Beaver River established around 1821, prioritized economic incentives like pelt collection over permanent settlement, though they laid groundwork for later European presence by mapping trade routes through the boreal landscape.[14] The extension of railway lines across Alberta following provincial confederation in 1905 facilitated a homesteading influx into northern areas, including around Cold Lake, where settlers cleared boreal forest for grain cultivation and livestock rearing despite challenges like short growing seasons and acidic soils. Homesteaders adapted pragmatic techniques, such as slash-and-burn clearing and mixed farming, to exploit arable pockets in the aspen parkland transition zone, driven by federal land grants under the Dominion Lands Act that incentivized agricultural development for economic self-sufficiency. Initial oil explorations in the 1920s identified heavy bitumen deposits underlying Cold Lake, prompting small-scale extraction efforts limited by primitive drilling technology and high viscosity of the resource.[15] These finds, confirmed through surface seeps and early wells, spurred investor interest in the region's petroleum potential, though commercial viability remained constrained until post-1930s advancements, reflecting the era's focus on resource scouting amid broader Alberta energy prospecting.[16]Establishment of Military Infrastructure

Following the end of the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) sought to establish new facilities to meet emerging Cold War defense requirements, including advanced air weapons training for jet aircraft. In 1952, the RCAF selected a site near Cold Lake, Alberta, for its first post-war flying station, citing the area's flat terrain, adequate drainage, and proximity to gravel deposits suitable for construction.[17] Construction commenced that year, with the station officially opening in the spring of 1954 under the command of Wing Commander John Watts.[17] Concurrently, the federal government pursued the creation of the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range (CLAWR) to support live-fire and tactical exercises, addressing the need for expansive, low-risk airspace amid supersonic jet development. In 1953, Canada signed perpetual lease agreements with the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan for a tract measuring approximately 180 km by 65 km, encompassing 1.17 million hectares of boreal forest and lakes that mimicked European training environments.[17] This range, spanning roughly 4,490 square miles across the provincial border, enabled unrestricted low-level flight and weapons practice, filling a critical gap in Canadian capabilities for all-weather fighter operations.[18] These developments represented substantial federal investment, with 40 major buildings—including hangars, barracks, and a hospital—completed by late 1954, alongside 355 permanent married quarters and additional civilian housing.[17] The infrastructure not only bolstered national defense by hosting early units like No. 3 All Weather (Fighter) Operational Training Unit but also integrated into broader Western alliances, facilitating pilot training that aligned with NATO's collective air defense imperatives from the outset.[17] This spurred rapid economic and demographic expansion in the region, as military personnel and support roles drew workers and families to the previously sparse area.[17]Post-War Growth and Recent Economic Expansions

Following the expansion of in-situ heavy oil extraction techniques in the Cold Lake oil sands area during the 1960s and 1970s, particularly by Imperial Oil, which acquired leases in the 1950s and initiated pilot projects, the region's population began to urbanize rapidly to support workforce needs and associated services.[19] This growth, driven by proximity to bitumen deposits amenable to steam-based recovery, led to the incorporation of the Town of Cold Lake amid rising housing demands, with the community merging the Town of Grand Centre, Town of Cold Lake, and Medley on October 1, 1996, before achieving city status on October 1, 2000.[20] Population figures reflect this trajectory, increasing from approximately 1,400 in 1960 to over 7,000 by 2000, fueled by oil-related infrastructure and military base expansion.[21][22] In the 2010s, heavy oil production accelerated through steam-assisted methods, including cyclic steam stimulation at Imperial Oil's Cold Lake operations, which reached average daily bitumen output of 165,000 barrels by 2016 despite global price volatility from events like the 2014 oil crash.[23] Expansions such as the Nabiye project, approved in the early 2010s, boosted capacity toward 180,000 barrels per day, supporting thousands of direct and indirect jobs in the Cold Lake Oil Sands Area through heightened drilling, maintenance, and supply chain activities, even as employment fluctuated with commodity cycles.[24][25] Into the 2020s, economic expansions continued with over $525 million in major projects, encompassing upgrades to the CFB Cold Lake facility for F-35 operations, Pathways Alliance carbon capture infrastructure, and health services enhancements, alongside a $33 million wastewater treatment plant upgrade initiated in 2024 featuring advanced mechanical and chemical processes.[26][27] The CL Medical Clinic expansion, unveiled in September 2025, added over 15,000 square feet to address service gaps.[28] These initiatives sustained job growth amid broader Alberta oil sector resilience, though local reports highlighted pressures from inflation-driven cost escalations in goods and services, alongside rises in petty crime and vulnerable populations as noted in 2023 municipal assessments.[29][30]Paleontology

Quaternary Fossil Assemblages

Since the 2010s, underwater excavations in Cold Lake, particularly at French Bay on the Alberta side, have yielded over 250 subfossil vertebrate specimens from lakebed deposits, comprising 94% of the total recovered from the lake's three primary sites. These remains, dominated by large ungulates, represent at least 13 taxa consistent with post-Last Glacial Maximum faunas in western Canada.[31][32] Key identifications include steppe bison (Bison priscus), horse (Equus sp.), woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), and caribou (Rangifer tarandus), with additional fragments of bison jaws and horse teeth confirming megafaunal presence. Radiocarbon dating of seven specimens establishes ages from 10,350 ± 40 years BP to 161 ± 23 years BP, spanning the late Pleistocene-early Holocene transition and indicating faunal adaptation to environments exposed as glacial ice receded.[33][32][34] Waterlogging in the lacustrine setting has caused significant degradation, resulting in crumbling, friable bones requiring specialized conservation; the majority have been processed and analyzed at the Royal Alberta Museum, where they contribute to broader Quaternary paleontological collections from Alberta.[35][31]Significance of Discoveries

The fossils recovered from Cold Lake provide critical data for reconstructing late Quaternary boreal ecosystems in western Canada, revealing a diverse assemblage of at least 13 vertebrate taxa, including megafauna such as mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), horse (Equus ferus), and bison (Bison sp.), alongside smaller mammals and fish, indicative of heterogeneous post-glacial habitats ranging from forested uplands to lacustrine environments.[36] This diversity, dated between approximately 12,000 and 8,000 years before present via radiocarbon analysis, underscores the persistence of mixed faunal communities in northern Alberta following the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet around 13,000 years ago, offering empirical evidence against oversimplified models of rapid, uniform post-glacial homogenization.[35][36] These assemblages contribute to broader debates on megafauna extinction by documenting localized survival and turnover patterns that challenge synchronous, continent-wide extinction narratives, with radiocarbon dates showing staggered declines in taxa like proboscideans amid climatic warming rather than abrupt anthropogenic overkill in boreal settings.[38][36] Specifically, mammoth remains from Cold Lake align with migration corridors traced through Alberta's Quaternary record, where post-glacial recolonization from southern refugia is evidenced by tusk and bone fragments in museum collections, informing models of range dynamics driven by habitat connectivity and ice-free corridors.[39][38] Underwater recovery techniques employed at Cold Lake sites, such as French Bay, highlight taphonomic biases inherent in subaqueous deposition, where anaerobic lake bottoms favored preservation of articulated skeletons and subfossils over terrestrial exposures prone to weathering and scavenging, thus mitigating sampling gaps in the regional fossil record.[36][31] This methodological insight has implications for interpreting climate-driven faunal turnover, as the site's chronostratigraphic sequence correlates megafauna presence with the Younger Dryas cooling (circa 12,900–11,700 years ago) and subsequent Holocene warming, revealing adaptive responses like dietary shifts in herbivores evidenced by isotopic analysis of associated bones.[35][40]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Cold Lake is situated in east-central Alberta, Canada, approximately 290 kilometres northeast of Edmonton by road, within the Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87.[41] The city centre lies at roughly 54°28′N 110°11′W, near the province's eastern boundary with Saskatchewan, where the lake itself extends across the provincial line.[42] This positioning places Cold Lake in a transitional zone between the prairies to the south and the boreal plains to the north, facilitating connectivity to regional transportation networks like Highway 55. The eponymous Cold Lake covers a surface area of about 373 square kilometres, making it one of Alberta's larger lakes, with a maximum depth reaching 100 metres.[43] The lake's morphology features irregular shorelines, including bays such as Primrose and English Bay, which influence local hydrology and sediment distribution. Surrounding terrain consists predominantly of boreal forest interspersed with muskeg wetlands, characteristic of the region's glacial till and outwash deposits that support extensive wildlife corridors for species like moose, woodland caribou, and wolves.[44] These ecosystems extend into adjacent areas, including proximity to the Cold Lake oil sands deposits, which lie south of the main Athabasca formations.[45] The urban layout of Cold Lake integrates military installations, such as Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake to the south, with residential and light industrial zones clustered around the lake's western and northern shores, particularly near Primrose Lake section for operational facilities and English Bay for recreational access points. This configuration reflects adaptations to the lake's physical constraints, with development concentrated on flatter moraine uplands to minimize flood risks and preserve shoreline buffers.[46]Climate Patterns

Cold Lake features a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) typical of the boreal transition zone, with long, severe winters and short, warm summers driven by its northern latitude and continental influences.[47] The mean January temperature averages -13.4 °C, featuring daily highs around -10 °C and lows near -19 °C, reflecting persistent Arctic air masses and minimal solar heating.[48] In contrast, July means reach 16.8 °C, with average highs of 23-24 °C supporting brief periods of vegetation growth amid longer daylight hours.[48] Annual precipitation totals approximately 491 mm, predominantly as summer convective showers from June through August, when thunderstorms contribute over half the yearly amount due to instability from daytime heating over forested terrain.[48] Winters yield sparse snowfall, averaging under 150 cm, as cold, dry high-pressure systems dominate. Extreme cold events underscore variability, with the record low of -48.3 °C occurring on January 20, 1954, while boreal dryness elevates wildfire susceptibility, particularly in late spring and fall under low humidity and lightning ignition.[49][50] The large adjacent lake generates microclimatic moderation, reducing temperature extremes slightly compared to inland prairies and fostering advection fog during seasonal transitions, when warm air overlies cooler lake waters.[51] This fog, often persistent in autumn and spring, reduces visibility to aviation-critical levels at CFB Cold Lake, necessitating enhanced forecasting for military operations.[52] Long-term records from Environment Canada stations confirm these patterns, countering short-term anecdotal extremes with 30-year normals emphasizing continental aridity punctuated by convective events.[53]Demographics

Population Dynamics

The population of Cold Lake increased from 12,128 residents in 2001 to 15,661 in the 2021 federal census, reflecting sustained growth amid regional resource development, with Alberta government estimates placing it at 17,579 in 2024.[54][55][4] This expansion correlates with inflows tied to oil extraction activities in the Cold Lake oil sands area and the economic anchor of Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, which sustains employment for military personnel and support staff.[56][57] Demographic patterns show a median age of 32.4 years in 2021, younger than Alberta's provincial average, as military family relocations introduce cohorts with children and working-age adults, mitigating potential aging in the non-transient civilian base.[58] The 3.87% year-over-year rise to 2024 underscores volatility from sector-specific booms, including oilfield operations that draw short-term workers.[4] Base dependency manifests in transient patterns, with urban concentration in the city core—classified as a small population centre—contrasting rural fringes in the surrounding Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87, where commuting workers amplify housing pressures without permanent settlement.[59] Municipal censuses, such as the 2022 count of 16,302, highlight this flux, as rotational military postings and project-based oil employment exceed typical organic urban-rural balances.[60]Ethnic and Cultural Composition

According to the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Cold Lake's residents primarily reported ethnic or cultural origins of European descent, with English origins being the most common at 20.9%, followed by Scottish, German, Irish, and Canadian.[61] These groups collectively comprised over 70% of responses, reflecting historical settlement patterns in northern Alberta tied to resource industries and European immigration.[62] Visible minorities accounted for 10.2% of the population, lower than Alberta's provincial average of 23%.[63] The largest subgroups included Filipinos (4.7%) and South Asians (approximately 1.5%), often linked to labor in the oil sands and extraction sectors, which draw temporary and skilled workers from these regions.[61] [62] Other visible minority groups, such as Black and Chinese, were present in smaller numbers under 1% each.[62] The Indigenous population within the city limits stood at around 8-10%, including First Nations and Métis identities, with additional influence from adjacent reserves of the Cold Lake First Nations, a Cree band under Treaty 6.[64] These reserves, such as Cold Lake 149, support economies reliant on resource royalties from nearby oil developments, contributing to cross-community cultural exchanges despite separate governance.[65] Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake introduces further cultural diversity through its military personnel, including visible minorities and international exchange officers participating in multinational exercises like Maple Flag, which has prompted community adaptations such as multicultural events and multilingual services in retail and support sectors.[66] This base-driven influx complements the resource economy's immigrant labor, enhancing overall ethnic heterogeneity without dominating the European-majority composition.[67]Language and Religious Profiles

In the 2021 Census of Population, English was the mother tongue for 13,275 residents of Cold Lake, representing 84.8% of the total population of 15,661, while French accounted for 755 individuals (4.8%), Indigenous languages for 120 (0.8%), other non-official languages for 1,005 (6.4%), and multiple languages for 390 (2.5%).[68] Languages spoken most often at home showed even greater English dominance, with 94.8% of residents using it primarily, French at 4.8%, and non-official languages comprising just 3.16%.[69][70] Knowledge of official languages is near-universal, with nearly all residents proficient in English and a minority bilingual in French, reflecting Alberta's broader linguistic patterns where immigrant languages like Tagalog, Punjabi, or Arabic appear in trace amounts without establishing community thresholds.[71] Religious affiliation in Cold Lake, per the 2021 Census, features Christianity as the leading category, with Catholics numbering 3,740 or 24.4% of the population—the largest single group.[61] Other Christian groups, including Protestant denominations (e.g., United Church, Anglican, Lutheran) and unspecified Christians, contribute to an overall Christian majority exceeding 50% when aggregated, though precise breakdowns beyond Catholic are not itemized in municipal profiles; non-Christian faiths such as Islam, Hinduism, or Sikhism remain minimal, under 2% combined.[72] Secularism has grown, with "no religion" responses aligning with Alberta's provincial rise to about 35-40% in similar northern communities, driven by younger demographics and military transients.[73] The Canadian Forces Base influences religious support through multi-faith chaplaincies accommodating Protestant, Catholic, and other personnel needs, yet local surveys indicate persistent Christian cultural norms among civilians.[74]| Category | Key Statistic (2021 Census) |

|---|---|

| Mother Tongue: English | 84.8% (13,275 persons)[68] |

| Mother Tongue: French | 4.8% (755 persons)[68] |

| Home Language: English | 94.8%[69] |

| Religion: Catholic | 24.4% (3,740 persons)[61] |

| Overall Christian | >50% (aggregated denominations)[72] |

| No Religion | ~35-40% (regional proxy)[73] |

Economy

Oil and Gas Sector

Imperial Oil initiated commercial production from the Cold Lake oil sands in 1985 using cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), a thermal in-situ recovery technique suited to the deposit's deep, unmineable bitumen reservoirs at 300 to 600 meters depth. CSS operates through cycles of high-pressure steam injection to reduce bitumen viscosity, a soak period for heat distribution, and subsequent production via natural reservoir drive mechanisms including compaction and solution gas. This method has proven economically viable for heavy oil extraction, with field-scale implementation across multiple pads enabling scalable output despite the bitumen's high asphaltene content and low fluidity.[75][76][77] Production at Imperial's Cold Lake operations averaged 142,000 gross barrels per day in the first quarter of 2024, with historical volumes exceeding 150,000 barrels per day as of 2006. These outputs form part of Alberta's oil sands production, which reached an annual average of approximately 3.5 million barrels per day in 2024 amid record provincial crude volumes of up to 4.32 million barrels per day in mid-2025. The economics of CSS emphasize capital efficiency and recovery factors of 10-20% under current practices, sustaining operations through oil price cycles by leveraging fixed infrastructure costs against long-reserve-life assets estimated at billions of barrels in place.[78][77][79] Technological refinements, including multi-well sequential steaming patterns, have minimized water demands by optimizing interwell heat overlap and reducing overall injection volumes per barrel recovered. Recent pilots incorporate non-condensable gas co-injection to further curtail steam rates while maintaining production, addressing input cost volatility inherent to thermal processes. These advancements underpin job creation, with Cold Lake operations supporting thousands of direct and indirect roles in the resource-dependent Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake economic region, where extraction activities drive employment amid fluctuating labor markets.[80][81][82] The deposit's adjacency to Athabasca-area infrastructure, connected via pipelines like the Corridor system, integrates Cold Lake bitumen into provincial evacuation networks for upgrading and export, prioritizing secure domestic supply chains over volatile imported alternatives. This positioning enhances overall system reliability, as evidenced by sustained throughput despite regional bottlenecks, reinforcing the sector's role in Alberta's non-renewable revenue base of $16.9 billion in oil sands royalties for fiscal 2022-23.[83][84]Military and Defense Contributions

Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Cold Lake, operated as 4 Wing, employs over 1,500 regular force members alongside hundreds of civilian staff, generating substantial payroll expenditures that circulate through the local economy.[85] [86] A regional economic sector profile estimates the base's direct and indirect spending impact at $235.6 million annually, including local procurement for services and supplies, which sustains multiplier effects in retail, housing, and utilities sectors.[87] This infusion supports fiscal efficiency in national defense by leveraging centralized operations to minimize redundant infrastructure costs across the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).[3] As a key training hub, 4 Wing hosts operational training units for the CF-18 Hornet fleet, conducting pilot and weapons systems instruction that optimizes resource allocation for fleet readiness.[88] Preparations for the F-35 Lightning II transition include awarded contracts for specialized facilities, such as a $9.2 million design for fighter jet operations and maintenance infrastructure, further concentrating defense investments to enhance training economies of scale.[89] These activities reduce overall program costs by utilizing existing range and simulation assets, avoiding dispersed basing expenses.[90] The base's demands have fostered ancillary industries, particularly in aviation maintenance, with firms like Arcfield Canada establishing local warehouses for CF-18 avionics support and supply chain management.[91] Municipal initiatives, including a hangar acquisition at Cold Lake Regional Airport for an Aircraft Maintenance Engineering school, draw on base-related expertise to build skilled labor pools and attract private sector contracts.[92] Such developments extend procurement chains, employing technicians and engineers in roles tied to RCAF sustainment needs.[93]Tourism and Retail Activities

Cold Lake's tourism revolves around recreational activities on its expansive 373-square-kilometre lake, including boating, swimming, and angling for walleye, northern pike, and lake trout. Kinosoo Beach, a developed sandy shoreline with a splash park, playground, and volleyball courts, draws local residents and visitors for summer leisure.[94][95] The lake's fishery supports events like the annual Cold Lake Summer Fishing Derby, which sold out with 250 participants in 2021 targeting large lake trout.[96] The biennial Cold Lake Air Show, hosted by Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, enhances tourism by attracting around 21,000 spectators in 2024 for aerial demonstrations, static aircraft displays, and related festivities, generating increased local spending on hospitality and services without primary reliance on external subsidies.[97][98][99] Retail activity thrives due to the community's role as a commercial center for a trading area of approximately 50,000 people, bolstered by military base personnel and seasonal visitors. Major anchors such as Walmart Supercentre, Canadian Tire, and Sobeys, alongside over 570 licensed businesses, capitalize on steady traffic from these sources.[26][100]Government and Politics

Municipal Governance

Cold Lake employs a mayor-council form of government, consisting of a mayor elected at-large and six councillors also elected at-large on a citywide basis for staggered four-year terms.[101][102] Council holds regular public meetings on the second and fourth Tuesdays of each month at 6:00 p.m. in City Hall chambers, facilitating community input and decision-making on local bylaws, services, and finances.[101] This structure promotes direct accountability to residents through open sessions and annual reporting, with the mayor serving as the chief elected official overseeing council agendas and representing the city externally.[103] The municipality was incorporated as a city on October 1, 2000, marking its transition to full urban status with greater fiscal and administrative autonomy from provincial oversight under Alberta's Municipal Government Act.[20] Prior milestones include village incorporation effective December 31, 1953, and town status on January 1, 1979, reflecting population growth tied to regional resource development and military presence.[104] These evolutions enabled Cold Lake to manage expanding infrastructure needs independently, including utilities, roads, and public safety, while adhering to provincial standards for transparency and debt limits. Fiscal policies emphasize balanced budgets funded primarily through property taxes, utility fees, and provincial/federal grants, with council approving multi-year plans annually to prioritize capital investments. The 2023 capital budget totaled $23,308,000, focusing on infrastructure expansions such as equipment replacements and facility upgrades amid inflationary pressures, supported by a 3.3% residential property tax increase.[105][106] Accountability metrics include audited financial statements and performance reports, ensuring expenditures align with resident-approved strategic plans rather than external ideological directives. Public safety governance involves contracting RCMP services under Alberta's contract policing model, with 2023 priorities addressing rising property crimes (up 24%) through enhanced community engagement and enforcement.[107][108] Council advanced a dedicated policing committee in late 2023 to improve oversight, data-driven crime reduction strategies, and coordination with detachment priorities like drug enforcement, fostering measurable outcomes over vague policy rhetoric.[109][110]Interjurisdictional Relations

The City of Cold Lake maintains complex interjurisdictional ties with the federal government primarily through Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) for Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake (4 Wing), where federal properties are exempt from municipal taxation but compensated via federal payments to offset lost revenue for local services. In July 2025, the Federal Court of Appeal ruled in the city's favor in a long-standing dispute, determining that the Department of National Defence had undervalued the base's assessed value, potentially entitling Cold Lake to nearly $14 million in back payments over the prior decade; this decision reinforces municipal claims against federal assessments under the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act.[111][112] Provincially, Alberta's collection of oil royalties from the Cold Lake oil sands region—yielding billions in non-renewable resource revenue annually, such as $25.2 billion in 2023/24—indirectly supports municipal services in resource-dependent areas like Cold Lake through provincial grants and transfers, though local funding remains strained by volatile prices and limited direct municipal shares.[113] Alberta officials have criticized the federal equalization program, which redistributes fiscal capacity without accounting for resource volatility, arguing it disadvantages provinces like Alberta that contribute disproportionately via federal taxes without receiving payments, exacerbating tensions over resource-derived wealth transfer.[114][115] Intergovernmental relations also involve Cold Lake First Nations (CLFN), a Treaty 6 signatory, in multi-party agreements addressing land use and environmental impacts from federal military operations overlapping traditional territories. A 2020 conservation agreement among CLFN, the federal Ministers of National Defence and Environment, and the Government of Alberta establishes a framework for collaborative actions to protect boreal woodland caribou at the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range, including monitoring, habitat restoration, and traditional knowledge integration, while ensuring compliance with species-at-risk obligations under federal and provincial law.[116] CLFN has pursued specific claims settlements, such as the 2002 agreement resolving historical reserve issues, and advocates for benefit-sharing from resource development, contending that the 1930 transfer of natural resources to Alberta lacked First Nations consent under treaty terms.[117][118]Military Installations

Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake

Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, operated as 4 Wing by the Royal Canadian Air Force, serves as the primary tactical training hub for fighter pilots and provides multi-role combat-capable forces for domestic and international operations.[3] It hosts squadrons equipped with CF-188 Hornet aircraft, emphasizing air defense, ground attack, and operational readiness.[119] The base maintains alert postures under NORAD commitments, contributing to North American aerospace defense through rapid response capabilities.[120] Key infrastructure includes runways exceeding 3,000 meters in length, enabling operations of supersonic aircraft such as the CF-188, which achieves speeds up to Mach 1.8.[119] Advanced simulation centers support pilot training, with upgrades to flight training devices like the CT-155 Hawk system enhancing fidelity for lead-in fighter instruction.[121] Additional funding announced in 2013 bolstered training facilities and infrastructure to sustain high-tempo activities.[122] The base supports approximately 1,750 regular military members and 450 civilian personnel, with additional reserves contributing to operational scale.[57] It hosts international exercises such as Maple Flag, a biennial event simulating complex combat scenarios with coalition partners to improve interoperability.[123] These activities underscore 4 Wing's role in preparing forces for real-world contingencies without reliance on adjacent ranges.Cold Lake Air Weapons Range

The Cold Lake Air Weapons Range (CLAWR) encompasses approximately 11,700 square kilometers of restricted airspace and surface area straddling the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, representing the largest such facility in Canada dedicated to air-to-ground and air-to-air training. This expanse supports intensive live-fire exercises, precision-guided munitions drops, bombing simulations, and tactical maneuvers, enabling pilots to conduct operations from low altitudes up to supersonic speeds in a controlled environment with over 640 fixed and mobile targets. The range's vast, largely unpopulated terrain—comprising forests, wetlands, and lakes—facilitates realistic combat scenarios while accommodating international allies through multinational exercises like Maple Flag.[3][124][125] Operational protocols emphasize layered safety measures, including radar surveillance, real-time telemetry for weapon tracking, and designated exclusion zones to restrict civilian access, with oil and gas activities permitted only under coordinated approvals to avoid interference. Established in 1952 through agreements with provincial governments, the range incorporates instrumentation for automated impact assessment, which limits ground-based observers and reduces exposure to hazards during high-volume firing. Safety records reflect rigorous adherence to these protocols, though incidents such as CF-18 Hornet crashes in 2016 highlight the inherent risks of high-performance training; investigations attributed these to pilot error rather than systemic range deficiencies, underscoring the facility's role in honing skills that enhance overall mission survivability.[126][127][128] The range's strategic utility lies in its capacity to deliver unrestricted, full-spectrum training that prepares Canadian and allied forces for modern aerial warfare, contributing to national defense readiness amid evolving threats. Environmental stewardship includes ongoing biodiversity assessments by entities like the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, with Department of National Defence audits confirming that military activities result in minimal long-term ecological disruption through targeted mitigation, such as habitat monitoring and spill response protocols.[17][129][128]Education and Health Services

Educational Institutions

Northern Lights Public Schools and Lakeland Catholic School Division provide K-12 education to students in Cold Lake, with additional options through French immersion at École Voyageur and private faith-based instruction at Lakeland Christian Academy.[130][131][132][133] Public institutions under Northern Lights include Cold Lake Elementary School for early grades, Cold Lake Junior High for intermediate levels, Nelson Heights Middle School, and Cold Lake High School, which serves over 500 students in grades 10-12 with academic, knowledge and employability, and Career and Technology Studies programming tailored to local industries.[134][135][136] Lakeland Catholic operates schools such as Holy Cross Catholic School, emphasizing faith-integrated curricula from kindergarten through grade 12.[137] Specialized programs align vocational training with Cold Lake's military and resource sectors; Art Smith Aviation Academy, an alternative public school at Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, focuses on aviation-themed STEM education for grades K-9, leveraging proximity to the air base for practical exposure.[138] High schools incorporate Career and Technology Studies courses in areas like mechanics and resource technology, supporting pathways into oil sands operations and defense-related roles.[136] Portage College maintains a campus in the Cold Lake Energy Centre, delivering certificate and diploma programs in business administration, health and wellness, and environmental studies that prepare students for energy sector employment.[139][140] High school enrollment stood at 1,110 students in 2023, up 11.2% from the prior year, tracking regional population fluctuations driven by military and oil activities.[141] Local schools report strong graduation outcomes, with overall performance rated above average and contributing to workforce readiness in technical fields.Healthcare Facilities

The Cold Lake Healthcare Centre, operated by Alberta Health Services, serves as the primary acute care facility in the region, offering a 24/7 emergency department, inpatient services, and diagnostic imaging. Located at 314 25 Street, it handles major trauma, cardiac events, and general emergencies for both civilian and military populations.[142][143] Primary care is supplemented by on-site clinics including the Cold Lake Primary Care Network (PCN) Clinic and Lakeland Medical Clinic on the second floor, which provide family medicine and chronic disease management.[144] Canadian Armed Forces personnel at CFB Cold Lake primarily access care through the 22 Canadian Forces Health Services Centre, located at Building 881 Kingsway Road on the base, which delivers outpatient medical and dental services tailored to military needs.[145] Civilian access to base facilities is limited, but the Cold Lake Healthcare Centre integrates services for both groups under provincial agreements, including primary health care for CAF members in the community.[146] In response to physician shortages exacerbated by the area's remote location, local efforts in the 2020s have focused on recruitment and infrastructure expansion. The City of Cold Lake acquired the Glacier Gate Medical Clinic in 2023 for $1.85 million to retain and attract doctors, increasing the number of physicians at the Cold Lake Medical Clinic from two to six by 2025, with a seventh anticipated soon.[147][148] Expansion plans unveiled in September 2025 include adding examination rooms, physician offices, and a larger waiting area to improve patient flow and support further recruitment.[28] Additionally, in October 2025, the city committed up to $1.75 million to partner with CGA Medical Imaging for an on-site MRI machine, aiming to reduce reliance on distant facilities like those in Edmonton.[149] Despite these initiatives, challenges persist, including temporary service disruptions such as the obstetrical suspension from October 23 to 28, 2025, due to OB/GYN shortages, and broader rural recruitment hurdles addressed through programs like the Rural Physician Action Plan's RESIDE initiative, which placed one physician in Cold Lake by 2022.[150][151] Community organizations, including Hearts for Healthcare and the Cold Lake Chamber of Commerce, continue to advocate for streamlined licensing of foreign-trained physicians to bolster local capacity.[152][153]Culture and Community Life

Museums and Heritage Preservation

The Cold Lake Museums, a non-profit organization operating from a former Cold War-era radar station at 3699 69 Avenue, encompasses four specialized facilities dedicated to preserving local history: the Air Force Museum, Oil & Gas Interpretive Museum, Heritage Museum, and Indigenous Museum.[154][155] These museums collectively maintain artifacts and exhibits illustrating the region's military, industrial, settler, and Indigenous heritage, with public access facilitated through connected buildings and interactive displays.[156] The Cold Lake Air Force Museum, accredited by the Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services, focuses on the history of 4 Wing Cold Lake since its establishment in 1952, featuring galleries with Royal Canadian Air Force artifacts such as a Forward Looking Infrared Pod, F-5 components, and displays on squadrons from the post-World War II era through modern operations, including an outdoor airpark and radome.[157][158] It preserves relics from Cold War radar operations, marking it as the only such station in Canada repurposed as an aviation museum.[158] The Oil & Gas Interpretive Museum exhibits technologies and developments in the local oil sands extraction industry, covering geological history, drilling innovations, and Imperial Oil's contributions since the 1960s bitumen production.[159][160] The Heritage Museum houses artifacts from early 20th-century settlement, including tools, furnishings, and documents predating the dominance of military and resource extraction activities.[155] The Indigenous Museum displays Cree cultural items, traditional practices, and historical interactions with the land and settlers.[154] These institutions collaborate to ensure preservation of military and civilian relics, supported by provincial historic site recognition and grants for site maintenance, such as those for the Northern Defence Radar Station.[160][161] Admission is structured with adult rates at $8, family passes at $20, and free entry for children under 5, promoting broad public engagement.[162]Sports and Recreational Opportunities

Cold Lake supports competitive junior hockey through teams such as the Junior A Cold Lake Aeros and Junior B Cold Lake Ice, which play at Imperial Oil Place within the Cold Lake Energy Centre.[163] The arena features an NHL-sized ice surface and seats up to 2,500 spectators, attracting regional audiences for games and supporting local minor hockey and figure skating programs.[164] These facilities contribute to community engagement, with the Energy Centre hosting various ice sports that foster youth athletic development and draw crowds from surrounding areas.[165] Outdoor recreation centers on Cold Lake, offering boating, water skiing, fishing, and swimming, particularly at Kinosoo Beach and Cold Lake Provincial Park.[166] The lake supports world-class lake trout fishing and features boat launches for water sports, alongside 9 kilometers of trails for hiking and cycling in the provincial park.[167] Winter activities include ice fishing and cross-country skiing, enhancing year-round participation that promotes physical health among residents.[168] Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, through 4 Wing Personnel Support Programs, sponsors events like the annual CAF Sports Day and Summer Sports Day to encourage fitness among military personnel and families.[169] These gatherings, such as the 2017 CAF Sports Day with approximately 900 participants across 10 events, emphasize teamwork and healthy competition, supporting transient base populations' well-being.[170] Recent iterations in 2023 and planned for 2025 continue this tradition, integrating sports like running and team games to boost morale and physical activity.[171]Media and Popular Culture Representations

Cold Lake has appeared as a filming location for several productions, including the 2010 action film The A-Team, which utilized the area's landscapes for exterior shots, and the 2005 science fiction film The Island, though these do not prominently feature the community in narrative contexts.[172] A 1992 episode of the Canadian television series Degrassi Talks titled "Depression" was also shot there, focusing on youth issues without emphasizing local landmarks.[172] Documentaries highlighting Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake operations include a 1980s historical film detailing the base's units and aircraft such as the CF-104 and early CF-18 Hornets, produced for internal military viewing.[173] More recent aviation content, such as the Royal Canadian Air Force's "Day in the Life" series episode from February 2024, showcases CF-18 Hornet training at 4 Wing Cold Lake, emphasizing air-to-air and air-to-ground missions.[174] Coverage of low-level CF-18 training has appeared in aviation media, including segments following incidents like the 2013 crash near the base.[175] Local media extensively covers the biennial Cold Lake Air Show, hosted by 4 Wing, which drew 21,000 attendees in July 2024 despite smoky conditions from wildfires, featuring demonstrations by the CF-18 Hornet team and international acts like the Italian Frecce Tricolori.[176] Outlets such as Global News and Lakeland Today report on these events, often including premier Danielle Smith's attendance and practice sessions, positioning the air show as a key regional spectacle celebrating the RCAF's centennial.[177][178] Indigenous-focused films produced by Cold Lake First Nations members, such as the 2025 premiere of The Nation at Grand Square Cinema, explore themes of sovereignty and resource revenues on reserve lands, with production centered locally.[179] The 2023 documentary Three Circles, filmed entirely in the Łuéchogh Túé area, documents community resilience among First Nations residents.[180] Cold Lake lacks widespread depictions in mainstream popular culture, with external recognition largely tied to military aviation rather than fictional narratives or celebrity associations.[181]Environmental and Resource Debates

Impacts of Oil Sands Development

A 2024 study published in Science utilized aircraft-based measurements to quantify volatile organic compound emissions from 15 Alberta oil sands facilities, revealing that actual releases of organic carbon aerosols—precursors to pollutants like benzene and formaldehyde—were 20 to 64 times higher than figures reported to provincial inventories by industry operators. These underestimations, attributed to inadequate ground-based monitoring of diffuse sources such as uncombusted flares and evaporation ponds, affect air quality in surrounding areas including the Cold Lake region, where in-situ extraction dominates.[182] Independent verifications contrast with industry self-reports, highlighting systemic gaps in emission accounting despite regulatory requirements under Alberta's Specified Gas Reporting system.[183] In-situ methods prevalent at Cold Lake, such as cyclic steam stimulation employed by Imperial Oil, introduce groundwater risks through high-pressure fluid injection that can fracture caprock and mobilize bitumen plumes.[184] Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) monitoring data from operator programs indicate that detected plumes in the Cold Lake oil sands area have remained largely contained within targeted formations, with no widespread migration to potable aquifers reported as of 2023.[185] However, peer-reviewed assessments identify persistent vulnerabilities, including insufficient baseline hydrogeological data and challenges in attributing changes to extraction versus natural variability, underscoring the need for enhanced independent oversight beyond AER-approved plans.[186] Spill incidents underscore operational hazards: in 2013, Canadian Natural Resources Limited's Primrose facility near Cold Lake experienced multiple uncontrolled bitumen seepages from CSS wells, releasing over 1 million liters across 51 acres over several months due to undetected caprock fractures.[187] The AER investigation prompted mandatory well integrity upgrades, including better geomechanical modeling, yet the event exposed limitations in real-time detection for in-situ processes.[188] Similar seepages recurred in 2023 at other sites, contaminating surface waters and prompting First Nations concerns over unremediated toxins.[189] Local Indigenous communities, including Cold Lake First Nations, face compounded effects from habitat fragmentation and pollutant deposition, with the Cold Lake caribou herd declining 74% since the 1990s amid oil sands expansion, correlating with linear feature proliferation disrupting migration.[190] While provincial oil sands royalties—yielding CAD 3.7 billion in 2023—fund broader public services potentially benefiting reserves, direct allocations to affected bands via impact benefit agreements provide employment and revenue sharing that some leaders argue offset access restrictions on traditional lands.[191] Critiques from Cold Lake First Nations, however, emphasize unaccommodated treaty rights erosion and health risks from bioaccumulative toxins in fish and game, with limited transparency in industry-funded monitoring raising doubts about net gains.[118][192]Balancing Extraction with Ecological Concerns