Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Filipinos

View on Wikipedia

Filipinos (Filipino: Mga Pilipino)[51] are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino, English, or other Philippine languages. Despite formerly being subject to Spanish administration, less than 1% of Filipinos are fluent in Spanish.[52] Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines each with its own language, identity, culture, tradition, and history.

Key Information

Names

[edit]The name Filipino, as a demonym, was derived from the term las Islas Filipinas 'the Philippine Islands',[53] the name given to the archipelago in 1543 by the Spanish explorer and Dominican priest Ruy López de Villalobos, in honor of Philip II of Spain.[54] During the Spanish period, natives of the Philippine islands were usually known in the Philippines itself by the generic terms indio ("Indian (native of the East Indies)") or indigena 'indigenous',[55] while the generic term chino ("Chinese"),[56][57] short for "indio chino" was used in Spanish America to differentiate from the Native American indios of the Spanish territories in the Americas and the West Indies. The term Filipino was sometimes added by Spanish writers to distinguish the indio chino native of the Philippine archipelago from the indio of the Spanish territories in the Americas.[56] [58][54] The term Indio Filipino appears as a term of self-identification beginning in the 18th century.[54]

In 1955, Agnes Newton Keith wrote that a 19th century edict prohibited the use of the word "Filipino" to refer to indios. This reflected popular belief, although no such edict has been found.[54] The idea that the term Filipino was not used to refer to indios until the 19th century has also been mentioned by historians such as Salah Jubair[59] and Renato Constantino.[60] However, in a 1994 publication the historian William Henry Scott identified instances in Spanish writing where "Filipino" did refer to "indio" natives.[61] Instances of such usage include the Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604) of Pedro Chirino, in which he wrote chapters entitled "Of the civilities, terms of courtesy, and good breeding among the Filipinos" (Chapter XVI), "Of the Letters of the Filipinos" (Chapter XVII), "Concerning the false heathen religion, idolatries, and superstitions of the Filipinos" (Chapter XXI), "Of marriages, dowries, and divorces among the Filipinos" (Chapter XXX),[62] while also using the term "Filipino" to refer unequivocally to the non-Spaniard natives of the archipelago like in the following sentence:

The first and last concern of the Filipinos in cases of sickness was, as we have stated, to offer some sacrifice to their anitos or diwatas, which were their gods.[63]

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas

In the Crónicas (1738) of Juan Francisco de San Antonio, the author devoted a chapter to "The Letters, languages and politeness of the Philippinos", while Francisco Antolín argued in 1789 that "the ancient wealth of the Philippinos is much like that which the Igorots have at present".[54] These examples prompted the historian William Henry Scott to conclude that during the Spanish period:

[...]the people of the Philippines were called Filipinos when they were practicing their own culture—or, to put it another way, before they became indios.[54]

— William Henry Scott, Barangay- Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society

While the Philippine-born Spaniards during the 19th century began to be called españoles filipinos, logically contracted to just Filipino, to distinguish them from the Spaniards born in Spain, they themselves resented the term, preferring to identify themselves as "hijo/s del país" ("sons of the country").[54]

In the latter half of the 19th century, ilustrados, an educated class of mestizos (both Spanish mestizos and Sangley Chinese mestizos, especially Chinese mestizos) and indios arose whose writings are credited with building Philippine nationalism. These writings are also credited with transforming the term Filipino to one which refers to everyone born in the Philippines,[64][65] especially during the Philippine Revolution and American Colonial Era and the term shifting from a geographic designation to a national one as a citizenship nationality by law.[64][60] Historian Ambeth Ocampo has suggested that the first documented use of the word Filipino to refer to Indios was the Spanish-language poem A la juventud filipina, published in 1879 by José Rizal.[66] Writer and publisher Nick Joaquin has asserted that Luis Rodríguez Varela was the first to describe himself as Filipino in print.[67] Apolinario Mabini (1896) used the term Filipino to refer to all inhabitants of the Philippines. Father Jose Burgos earlier called all natives of the archipelago as Filipinos.[68] In Wenceslao Retaña's Diccionario de filipinismos, he defined Filipinos as follows,[69]

todos los nacidos en Filipinas sin distincion de origen ni de raza.

All those born in the Philippines without distinction of origin or race.

— Wenceslao E. Retaña, Diccionario De Filipinismos: Con La Revisión De Lo Que Al Respecto Lleva Publicado La Real Academia Española

American authorities during the American colonial era also started to colloquially use the term Filipino to refer to the native inhabitants of the archipelago,[70] but despite this, it became the official term for all citizens of the sovereign independent Republic of the Philippines, including non-native inhabitants of the country as per the Philippine nationality law.[54] However, the term has been rejected as an identification in some instances by minorities who did not come under Spanish control, such as the Igorot and Muslim Moros.[54][60]

The lack of the letter "F" in the 1940–1987 standardized Tagalog alphabet (Abakada) caused the letter "P" to be substituted for "F", though the alphabets or writing scripts of some non-Tagalog ethnic groups included the letter "F". Upon official adoption of the modern, 28-letter Filipino alphabet in 1987, the term Filipino was preferred over Pilipino.[citation needed] Locally, some still use "Filipino" to refer to the people and "Pilipino" to refer to the language, but in international use "Filipino" is the usual form for both.

A number of Filipinos refer to themselves colloquially as "Pinoy" (feminine: "Pinay"), which is a slang word formed by taking the last four letters of "Filipino" and adding the diminutive suffix "-y". Or the non-gender or gender fluid form Pinxy (seldom used in the country but used amongst Filipino-American communities).

In 2020, the neologism Filipinx appeared; a demonym applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora and specifically referring to and coined by Filipino Americans[citation needed] imitating Latinx, itself a recently coined gender-inclusive alternative to Latino or Latina. An online dictionary made an entry of the term, applying it to all Filipinos within the Philippines or in the diaspora.[71] In actual practice, however, the term is unknown among and not applied to Filipinos living in the Philippines, and Filipino itself is already treated as gender-neutral. The dictionary entry resulted in confusion, backlash and ridicule from Filipinos residing in the Philippines who never identified themselves with the foreign term.[72][73]

Native Filipinos were also called Manilamen (or Manila men) by English-speaking regions or Tagalas by Spanish-speakers during the colonial era. They were mostly sailors and pearl-divers and established communities in various ports around the world.[74][75] One of the notable settlements of Manilamen is the community of Saint Malo, Louisiana, founded at around 1763 to 1765 by escaped slaves and deserters from the Spanish Navy.[76][77][78][79] There were also significant numbers of Manilamen in Northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands in the late 1800s who were employed in the pearl hunting industries.[80][81]

In Mexico (especially in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Colima), Filipino immigrants arriving to New Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries via the Manila galleons were called chino, which led to the confusion of early Filipino immigrants with that of the much later Chinese immigrants to Mexico from the 1880s to the 1940s. A genetic study in 2018 has also revealed that around one-third of the population of Guerrero have 10% Filipino ancestry.[82][83]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]The oldest archaic human remains in the Philippines are the "Callao Man" specimens discovered in 2007 in the Callao Cave in Northern Luzon. They were dated in 2010 through uranium-series dating to the Late Pleistocene, c. 67,000 years old. The remains were initially identified as modern human, but after the discovery of more specimens in 2019, they have been reclassified as being members of a new species – Homo luzonensis.[84][85]

The oldest indisputable modern human (Homo sapiens) remains in the Philippines are the "Tabon Man" fossils discovered in the Tabon Caves in the 1960s by Robert B. Fox, an anthropologist from the National Museum. These were dated to the Paleolithic, at around 26,000 to 24,000 years ago. The Tabon Cave complex also indicates that the caves were inhabited by humans continuously from at least 47,000 ± 11,000 years ago to around 9,000 years ago.[86][87] The caves were also later used as a burial site by unrelated Neolithic and Metal Age cultures in the area.[88]

The Tabon Cave remains (along with the Niah Cave remains of Borneo and the Tam Pa Ling remains of Laos) are part of the "First Sundaland People", the earliest branch of anatomically modern humans to reach Island Southeast Asia at the time of lowered sea levels of Sundaland, with only one 3 km sea crossing.[89] They entered the Philippines from Borneo via Palawan at around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. Their descendants are collectively known as the Negrito people, although they are highly genetically divergent from each other. Philippine Negritos show a high degree of Denisovan Admixture, similar to Papuans and Indigenous Australians, in contrast to Malaysian and Andamanese Negritos (the Orang Asli). This indicates that Philippine Negritos, Papuans, and Indigenous Australians share a common ancestor that admixed with Denisovans at around 44,000 years ago.[90] Negritos include ethnic groups like the Aeta (including the Agta, Arta, Dumagat, etc.) of Luzon, the Ati of Western Visayas, the Batak of Palawan, and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. Today they comprise just 0.03% of the total Philippine population.[91]

After the Negritos, were two early Paleolithic migrations from East Asian (basal Austric, an ethnic group which includes Austroasiatics) people, they entered the Philippines at around 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, respectively. Like the Negritos, they entered the Philippines during the lowered sea levels during the last ice age, when the only water crossings required were less than 3 km wide (such as the Sibutu strait).[89] They retain partial genetic signals among the Manobo people and the Sama-Bajau people of Mindanao.

The last wave of prehistoric migrations to reach the Philippines was the Austronesian expansion which started in the Neolithic at around 4,500 to 3,500 years ago, when a branch of Austronesians from Taiwan (the ancestral Malayo-Polynesian-speakers) migrated to the Batanes Islands and Luzon. They spread quickly throughout the rest of the islands of the Philippines and became the dominant ethnolinguistic group. They admixed with the earlier settlers, resulting in the modern Filipinos – which though predominantly genetically Austronesian still show varying genetic admixture with Negritos (and vice versa for Negrito ethnic groups which show significant Austronesian admixture).[92][93] Austronesians possessed advanced sailing technologies and colonized the Philippines via sea-borne migration, in contrast to earlier groups.[94][95]

Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, and parts of Mainland Southeast Asia. From there, they colonized the rest of Austronesia, which in modern times include Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar, in addition to Maritime Southeast Asia and Taiwan.[95][96]

The connections between the various Austronesian peoples have also been known since the colonial era due to shared material culture and linguistic similarities of various peoples of the islands of the Indo-Pacific, leading to the designation of Austronesians as the "Malay race" (or the "Brown race") during the age of scientific racism by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.[97][98][99] Due to the colonial American education system in the early 20th century, the term "Malay race" is still used incorrectly in the Philippines to refer to the Austronesian peoples, leading to confusion with the non-indigenous Melayu people.[100][101][102][103]

Archaic epoch (to 1565)

[edit]Since at least the 3rd century, various ethnic groups established several communities. These were formed by the assimilation of various native Philippine kingdoms.[91] South Asian and East Asian people together with the people of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, traded with Filipinos and introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the native tribes of the Philippines. Most of these people stayed in the Philippines where they were slowly absorbed into local societies.

Many of the barangay (tribal municipalities) were, to a varying extent, under the de jure jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Srivijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Brunei, Malacca, Tamil Chola, Champa and Khmer empires, although de facto had established their own independent system of rule. Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Cambodia, Malay Peninsula, Indochina, China, Japan, India and Arabia. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

Even scattered barangays, through the development of inter-island and international trade, became more culturally homogeneous by the 4th century. Hindu-Buddhist culture and religion flourished among the noblemen in this era.

In the period between the 7th to the beginning of the 15th centuries, numerous prosperous centers of trade had emerged, including the Kingdom of Namayan which flourished alongside Manila Bay,[104][105] Cebu, Iloilo,[106] Butuan, the Kingdom of Sanfotsi situated in Pangasinan, the Kingdom of Luzon now known as Pampanga which specialized in trade with most of what is now known as Southeast Asia and with China, Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu in Okinawa.

From the 9th century onwards, a large number of Arab traders from the Middle East settled in the Malay Archipelago and intermarried with the local Malay, Bruneian, Malaysian, Indonesian and Luzon and Visayas indigenous populations.[107]

In the years leading up to 1000 AD, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous barangays (settlements ranging in size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajahs or sultans[108] or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". Nations such as the Wangdoms of Pangasinan and Ma-i as well as Ma-i's subordinates, the Barangay states of Pulilu and Sandao; the Kingdoms of Maynila, Namayan, and Tondo; the Kedatuans of Madja-as, Dapitan, and Cainta; the Rajahnates of Cebu, Butuan and Sanmalan; and the Sultanates of Buayan, Maguindanao, Lanao and Sulu; existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan.[109][110][111][112] Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.[113][114][115]

-

Tagalog maharlika, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Tagalog maginoo, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan kadatuan, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Native commoner women, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan timawa, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan pintados (tattooed), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan uripon (slaves), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

Historic caste systems

[edit]Datu – The Tagalog maginoo, the Kapampangan ginu and the Visayan tumao were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families or a ruling class.

Timawa – The timawa class were free commoners of Luzon and the Visayas who could own their own land and who did not have to pay a regular tribute to a maginoo, though they would, from time to time, be obliged to work on a datu's land and help in community projects and events. They were free to change their allegiance to another datu if they married into another community or if they decided to move.

Maharlika – Members of the Tagalog warrior class known as maharlika had the same rights and responsibilities as the timawa, but in times of war they were bound to serve their datu in battle. They had to arm themselves at their own expense, but they did get to keep the loot they took. Although they were partly related to the nobility, the maharlikas were technically less free than the timawas because they could not leave a datu's service without first hosting a large public feast and paying the datu between 6 and 18 pesos in gold – a large sum in those days.

Alipin – Commonly described as "servant" or "slave". However, this is inaccurate. The concept of the alipin relied on a complex system of obligation and repayment through labor in ancient Philippine society, rather than on the actual purchase of a person as in Western and Islamic slavery. Members of the alipin class who owned their own houses were more accurately equivalent to medieval European serfs and commoners.

By the 15th century, Arab and Indian missionaries and traders from Malaysia and Indonesia brought Islam to the Philippines, where it both replaced and was practiced together with indigenous religions. Before that, indigenous tribes of the Philippines practiced a mixture of Animism, Hinduism and Buddhism. Native villages, called barangays were populated by locals called Timawa (Middle Class/freemen) and Alipin (servants and slaves). They were ruled by Rajahs, Datus and Sultans, a class called Maginoo (royals) and defended by the Maharlika (Lesser nobles, royal warriors and aristocrats).[91] These Royals and Nobles are descended from native Filipinos with varying degrees of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, which is evident in today's DNA analysis among South East Asian Royals. This tradition continued among the Spanish and Portuguese traders who also intermarried with the local populations.[116]

Spanish period (1521–1898)

[edit]

The first census in the Philippines was in 1591, based on tributes collected. The tributes counted the total founding population of the Spanish Philippines as 667,612 people.[117]: 177 [118][119] 20,000 were Chinese migrant traders,[120] at different times: around 15,600 individuals were Latino soldier-colonists who were cumulatively sent from Peru and Mexico and they were shipped to the Philippines annually,[121][122] 3,000 were Japanese residents,[123] and 600 were pure Spaniards from Europe.[124] There was a large but unknown number of South Asian Filipinos, as the majority of the slaves imported into the archipelago were from Bengal and Southern India,[125] adding Dravidian speaking South Indians and Indo-European speaking Bengalis into the ethnic mix.

The Philippines was governed by the Spaniards. The arrival of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (Portuguese: Fernão de Magalhães) in 1521 began a period of European immigration. During the Spanish period, the Philippines was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which was governed and administered from Mexico City. Early Spanish settlers were mostly explorers, soldiers, government officials and religious missionaries born in Spain and Mexico. Most Spaniards who settled were of Basque ancestry,[126] but there were also settlers of Andalusian, Catalan, and Moorish descent.[127] The Peninsulares (governors born in Spain), mostly of Castilian ancestry, settled in the islands to govern their territory. Most settlers married the daughters of rajahs, datus, and sultans to reinforce the alliances of the islands. The Ginoo and Maharlika castes (royals and nobles) in the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spaniards formed the privileged Principalía (nobility) during the early Spanish period.

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade that connected the Philippines through Manila to Acapulco in Mexico, attracted new waves of immigrants from China, as Manila was already previously connected to the Maritime Silk Road, as shown in the Selden Map, from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in Southern Fujian to Manila, maritime trade flourished during the Spanish period, especially as Manila was connected to the ports of Southern Fujian, such as Yuegang (the old port of Haicheng in Zhangzhou, Fujian).[128][129] The Spaniards recruited thousands of Chinese migrant workers from "Chinchew" (Quanzhou), "Chiõ Chiu" (Zhangzhou), "Canton" (Guangzhou), and Macau called sangleys (from Hokkien Chinese: 生理; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sng-lí; lit. 'business') to build the colonial infrastructure in the islands. Many Chinese immigrants converted to Christianity, intermarried with the locals, and adopted Hispanized names and customs and became assimilated, although the children of unions between Filipinos and Chinese that became assimilated continued to be designated in official records as mestizos de sangley. The Chinese mestizos were largely confined to the Binondo area until the 19th century. However, they eventually spread all over the islands and became traders, landowners and moneylenders. Today, their descendants still comprise a significant part of the Philippine population especially its bourgeois,[130] who during the late Spanish Era in the late 19th century, produced a major part of the ilustrado intelligentsia of the late Spanish Philippines, that were very influential with the creation of Filipino nationalism and the sparking of the Philippine Revolution as part of the foundation of the First Philippine Republic and subsequent sovereign independent Philippines.[131][132] Today, the bulk of the families in the list of the political families in the Philippines have such family background. Meanwhile, the Spanish-era Sangley's pure ethnic Chinese descendants of which, replenished by later migrants in the 20th century, that preserved at least some of their Chinese culture, integrated together with mainstream Filipino culture, are now in the form of the modern Chinese Filipino community, who currently play a leading role in the Philippine business sector and contribute a significant share of the Philippine economy today,[133][134][135][136][137] where most in the current list of the Philippines' richest each year comprise Taipan billionaires of Chinese Filipino background, mostly of Hokkien descent, where most still trace their roots back to mostly Jinjiang or Nan'an within Quanzhou or sometimes Xiamen (Amoy) or Zhangzhou, all within Southern Fujian, the Philippines' historical trade partner with Mainland China.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[138][failed verification] Many were assimilated throughout the centuries, especially through the tumultuous period of World War II. Today, there is a small growing Nikkei community of Japanese Filipinos in Davao with roots to the old Little Japan in Mintal or Calinan in Davao City during the American colonial period, where many had roots starting out in Abaca plantations or from workers of the Benguet Road (Kennon Road) to Baguio.

British forces occupied Manila between 1762 and 1764 as a part of the Seven Years' War. However, the only part of the Philippines which the British held was the Spanish capital of Manila and the principal naval port of Cavite, both of which are located by the Manila Bay. The war was ended by the Treaty of Paris (1763). At the end of the war the treaty signatories were not aware that Manila had been taken by the British and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Empire.[139] Many Indian Sepoy troops and their British captains mutinied and were left in Manila and some parts of the Ilocos and Cagayan. The Indian Filipinos in Manila settled at Cainta, Rizal and the ones in the north settled in Isabela. Most were assimilated into the local population. Even before the British invasion, there were already also a large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos as majority of the slaves imported into the archipelago were from Bengal or Southern India,[140] adding Dravidian speaking South Indians and Indo-European speaking Bangladeshis into the ethnic mix.

A total of 110 Manila-Acapulco galleons set sail between 1565 and 1815, during the Philippines trade with Mexico. Until 1593, three or more ships would set sail annually from each port bringing with them the riches of the archipelago to Spain. European criollos, mestizos and Portuguese, French and Mexican descent from the Americas, mostly from Latin America came in contact with the Filipinos. Japanese, Indian and Cambodian Christians who fled from religious persecutions and killing fields also settled in the Philippines during the 17th until the 19th centuries. The Mexicans especially were a major source of military migration to the Philippines and during the Spanish period they were referred to as guachinangos[141][142] and they readily intermarried and mixed with native Filipinos. Bernal, the author of the book "Mexico en Filipinas" contends, that they were middlemen, the guachinangos in contrast to the Spanish and criollos, known as Castila, that had positions in power and were isolated, the guachinangos in the meantime, had interacted with the natives of the Philippines, while in contrast, the exchanges between Castila and native were negligent. Following Bernal, these two groups—native Filipinos and the Castila—had been two "mutually unfamiliar castes" that had "no real contact." Between them, he clarifies however, were the Chinese traders and the guachinangos (Mexicans).[141] In the 1600s, Spain deployed thousands of Mexican and Peruvian soldiers across the many cities and presidios of the Philippines.[143]

| Location | 1603 | 1636 | 1642 | 1644 | 1654 | 1655 | 1670 | 1672 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manila[143] | 900 | 446 | — | 407 | 821 | 799 | 708 | 667 |

| Fort Santiago[143] | — | 22 | — | — | 50 | — | 86 | 81 |

| Cavite[143] | — | 70 | — | — | 89 | — | 225 | 211 |

| Cagayan[143] | 46 | 80 | — | — | — | — | 155 | 155 |

| Calamianes[143] | — | — | — | — | — | — | 73 | 73 |

| Caraga[143] | — | 45 | — | — | — | — | 81 | 81 |

| Cebu[143] | 86 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 135 | 135 |

| Formosa[143] | — | 180 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moluccas[143] | 80 | 480 | 507 | — | 389 | — | — | — |

| Otón[143] | 66 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 169 | 169 |

| Zamboanga[143] | — | 210 | — | — | 184 | — | — | — |

| Other[143] | 255 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| [143] | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total Reinforcements[143] | 1,533 | 1,633 | 2,067 | 2,085 | n/a | n/a | 1,632 | 1,572 |

With the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1867, Spain opened the Philippines for international trade. European investors of British, Dutch, German, Portuguese, Russian, Italian, and French nationality were among those who settled in the islands as business increased. More Spaniards and Chinese arrived during the next century. Many of these migrants intermarried with local mestizos and assimilated with the indigenous population.

In the late 1700s to early 1800s, Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, an Augustinian Friar, in his Two Volume Book: "Estadismo de las islas Filipinas"[144][145] compiled a census of the Spanish-Philippines based on the tribute counts (Which represented an average family of seven to ten children[146] and two parents, per tribute)[147] and came upon the following statistics:[144]: 539 [145]: 31, 54, 113

| Province | Native Tributes | Spanish Mestizo Tributes | All Tributes[a] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tondo[144]: 539 | 14,437-1/2 | 3,528 | 27,897-7 |

| Cavite[144]: 539 | 5,724-1/2 | 859 | 9,132-4 |

| Laguna[144]: 539 | 14,392-1/2 | 336 | 19,448-6 |

| Batangas[144]: 539 | 15,014 | 451 | 21,579-7 |

| Mindoro[144]: 539 | 3,165 | 3-1/2 | 4,000-8 |

| Bulacan[144]: 539 | 16,586-1/2 | 2,007 | 25,760-5 |

| Pampanga[144]: 539 | 16,604-1/2 | 2,641 | 27,358-1 |

| Bataan[144]: 539 | 3,082 | 619 | 5,433 |

| Zambales[144]: 539 | 1,136 | 73 | 4,389 |

| Ilocos[145]: 31 | 44,852-1/2 | 631 | 68,856 |

| Pangasinan[145]: 31 | 19,836 | 719-1/2 | 25,366 |

| Cagayan[145]: 31 | 9,888 | 0 | 11,244-6 |

| Camarines[145]: 54 | 19,686-1/2 | 154-1/2 | 24,994 |

| Albay[145]: 54 | 12,339 | 146 | 16,093 |

| Tayabas[145]: 54 | 7,396 | 12 | 9,228 |

| Cebu[145]: 113 | 28,112-1/2 | 625 | 28,863 |

| Samar[145]: 113 | 3,042 | 103 | 4,060 |

| Leyte[145]: 113 | 7,678 | 37-1/2 | 10,011 |

| Caraga[145]: 113 | 3,497 | 0 | 4,977 |

| Misamis[145]: 113 | 1,278 | 0 | 1,674 |

| Negros Island[145]: 113 | 5,741 | 0 | 7,176 |

| Iloilo[145]: 113 | 29,723 | 166 | 37,760 |

| Capiz[145]: 113 | 11,459 | 89 | 14,867 |

| Antique[145]: 113 | 9,228 | 0 | 11,620 |

| Calamianes[145]: 113 | 2,289 | 0 | 3,161 |

| TOTAL | 299,049 | 13,201 | 424,992-16 |

The Spanish-Filipino population as a proportion of the provinces widely varied; with as high as 19% of the population of Tondo province [144]: 539 (The most populous province and former name of Manila), to Pampanga 13.7%,[144]: 539 Cavite at 13%,[144]: 539 Laguna 2.28%,[144]: 539 Batangas 3%,[144]: 539 Bulacan 10.79%,[144]: 539 Bataan 16.72%,[144]: 539 Ilocos 1.38%,[145]: 31 Pangasinan 3.49%,[145]: 31 Albay 1.16%,[145]: 54 Cebu 2.17%,[145]: 113 Samar 3.27%,[145]: 113 Iloilo 1%,[145]: 113 Capiz 1%,[145]: 113 Bicol 20%,[148] and Zamboanga 40%.[148] According to the data, in the Archdiocese of Manila which administers much of Luzon under it, about 10% of the population was Spanish-Filipino.[144]: 539 Across the whole Philippines, as estimated, the total ratio of Spanish Filipino tributes amount to 5% of the totality.[144][145]

In the 1860s to 1890s, in the urban areas of the Philippines, especially at Manila, according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and the pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish Filipino and Chinese Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated. Eventually, many families belonging to the non-native categories from centuries ago beyond the late 19th century diminished because their descendants intermarried enough and were assimilated into and chose to self-identify as Filipinos while forgetting their ancestor's roots[149] since during the Philippine Revolution to modern times, the term "Filipino" was expanded to include everyone born in the Philippines coming from any race, as per the Philippine nationality law.[150][151] That would explain the abrupt drop of otherwise high Chinese, Spanish and mestizo, percentages across the country by the time of the first American census in 1903.[152] By the 20th century, the remaining ethnic Spaniards and ethnic Chinese, replenished by further Chinese migrants in the 20th century, now later came to compose the modern Spanish Filipino community and Chinese Filipino community respectively, where families of such background contribute a significant share of the Philippine economy today,[133][134][2][136][137] where most in the current list of the Philippines' richest each year comprise billionaires of either Chinese Filipino background or the old elite families of Spanish Filipino background.

Late modern

[edit]

After the defeat of Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino general, Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence on June 12 while General Wesley Merritt became the first American governor of the Philippines. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, with Spain ceding the Philippines and other territories to the United States in exchange for $20 million.[153][154]

The Philippine–American War resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 Filipino civilians.[155] Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to 1,000,000.[156][157] After the Philippine–American War, the United States civil governance was established in 1901, with William Howard Taft as the first American Governor-General.[158] A number of Americans settled in the islands and thousands of interracial marriages between Americans and Filipinos have taken place since then. Owing to the strategic location of the Philippines, as many as 21 bases and 100,000 military personnel were stationed there since the United States first colonized the islands in 1898. These bases were decommissioned in 1992 after the end of the Cold War, but left behind thousands of Amerasian children.[159] The country gained independence from the United States in 1946. The Pearl S. Buck International Foundation estimates there are 52,000 Amerasians scattered throughout the Philippines. However, according to the center of Amerasian Research, there might be as many as 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of Clark, Angeles City, Manila, and Olongapo.[160] In addition, numerous Filipino men enlisted in the US Navy and made careers in it, often settling with their families in the United States. Some of their second- or third-generation families returned to the country.

Following its independence, the Philippines has seen both small and large-scale immigration into the country, mostly involving American, European, Chinese and Japanese peoples. After World War II, South Asians continued to migrate into the islands, most of which assimilated and avoided the local social stigma instilled by the early Spaniards against them by keeping a low profile or by trying to pass as Spanish mestizos. This was also true for the Arab and Chinese immigrants, many of whom are also post WWII arrivals. More recent migrations into the country by Koreans, Persians, Brazilians, and other Southeast Asians have contributed to the enrichment of the country's ethnic landscape, language and culture. Centuries of migration, diaspora, assimilation, and cultural diversity made most Filipinos accepting of interracial marriage and multiculturalism.

Philippine nationality law is currently based upon the principle of jus sanguinis and, therefore, descent from a parent who is a citizen of the Republic of the Philippines is the primary method of acquiring national citizenship. Birth in the Philippines to foreign parents does not in itself confer Philippine citizenship, although RA9139, the Administrative Naturalization Law of 2000, does provide a path for administrative naturalization of certain aliens born in the Philippines. Since many of the above historical groups came to the Philippines before its establishment as an independent state, many have also gained citizenship before the founding of either the First Philippines Republic or Third Republic of the Philippines. For example, many Cold-War-era Chinese migrants who had relatives in the Philippines attain Filipino citizenship for their children through marriage with Chinese Filipino families that trace back to either the late Spanish Era or American Colonial Era. Likewise, many other modern expatriates from various countries, such as the US, often come to the Philippines to marry with a Filipino citizen, ensuring their future children attain Filipino citizenship and their Filipino spouses ensure property ownership.

Social classifications

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

During the Spanish period, Spaniards from Spain and Hispanic America mainly referred to Spaniards born in the Philippines (Spanish Filipinos) in Spanish: "Filipino/s" (m) or "Filipina/s" (f)[161][162][163][164][165][excessive citations] in relation to those born in Hispanic America called in Spanish: "Americano/s" (m) / "Americana/s" (f) or "Criollo/s", whereas the Spaniards born in the Philippines themselves called the Spaniards from Spain as "Peninsular/es" with themselves also referred to as "Insular/es".[165] Meanwhile, the caste system hierarchy and taxation system during the Spanish Times dictated that those of mixed descent were known as "Mestizo/s" (m) / "Mestiza/s" (f), specifically those of mixed Spanish and native Filipino descent were known as "Mestizo/s de Español" (Spanish Mestizos), whereas those of mixed Chinese and native Filipino descent were known as "Mestizo/s de Sangley" (Chinese Mestizos) and the mix of all of the above or a mix of Spanish and Chinese were known as "Tornatrás". Meanwhile, the ethnic Chinese migrants (Chinese Filipinos) were historically referred to as "Sangley/es" (from Hokkien Chinese: 生理; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sng-lí; lit. 'business'), while the natives of the Philippine islands were usually known by the generic term "Indio/s"[165] (lit. "Indian, native of the East Indies").

Filipinos of mixed ethnic origins are still referred today as mestizos. However, in common popular parlance, mestizos usually refer to Filipinos mixed with Spanish or any other European ancestry. Filipinos mixed with any other foreign ethnicities are named depending on the non-Filipino part. Historically though, it was the Mestizo de Sangley (Chinese Mestizo) that numbered the most among mestizos,[166] though the Mestizos de Español (Spanish Mestizos) carried more social prestige due to the caste system hierarchy that usually elevated Spanish blood and Christianized natives to the peak, while most descendants of the Mestizo de Sangley (Chinese Mestizo), despite assuming many of the important roles in the economic, social and political life of the nation, would readily assimilate into the fabric of Philippine society.

People classified as 'blancos' (whites) were the insulares or "Filipinos" (a person born in the Philippines of pure Spanish descent), peninsulares (a person born in Spain of pure Spanish descent), Español mestizos (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian and Spanish ancestry) and tornatrás (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian, Chinese and Spanish ancestry). Manila was racially segregated, with blancos living in the walled city of Intramuros, un-Christianized sangleys in Parían, Christianized sangleys and mestizos de sangley in Binondo and the rest of the 7,000 islands for the indios, with the exception of Cebu and several other Spanish posts. Only mestizos de sangley were allowed to enter Intramuros to work for whites (including mestizos de español) as servants and various occupations needed for the colony. Indio were native Austronesians, but as a legal classification, Indio were those who embraced Roman Catholicism and Austronesians who lived in proximity to the Spanish colonies.[citation needed]

People who lived outside Manila, Cebu and the major Spanish posts were classified as such: 'Naturales' were Catholic Austronesians of the lowland and coastal towns. The un-Catholic Negritos and Austronesians who lived in the towns were classified as 'salvajes' (savages) or 'infieles' (the unfaithful). 'Remontados' (Spanish for 'situated in the mountains') and 'tulisanes' (bandits) were indigenous Austronesians and Negritos who refused to live in towns and took to the hills, all of whom were considered to live outside the social order as Catholicism was a driving force in Spanish everyday life, as well as determining social class in the territory. People of pure Spanish descent living in the Philippines who were born in Spanish America were classified as 'americanos'. Mestizos and africanos born in Spanish America living in the Philippines kept their legal classification as such and usually came as indentured servants to the 'americanos'. The Philippine-born children of 'americanos' were classified as 'Ins'. The Philippine-born children of mestizos and Africanos from Spanish America were classified based on patrilineal descent.

The term negrito was coined by the Spaniards based on their appearance. The word 'negrito' would be misinterpreted and used by future European scholars as an ethnoracial term in and of itself. Both Christianized negritos who lived in the archipelago and un-Christianized negritos who lived in tribes outside were classified as 'negritos'. Christianized negritos who lived in Manila were not allowed to enter Intramuros and lived in areas designated for indios.

A person of mixed Negrito and Austronesian ancestry were classified based on patrilineal descent; the father's ancestry determined a child's legal classification. If the father was 'negrito' and the mother was 'India' (Austronesian), the child was classified as 'negrito'. If the father was 'indio' and the mother was 'negrita', the child was classified as 'indio'. Persons of Negrito descent were viewed as being outside the social order as they usually lived in tribes outside and resisted conversion to Christianity.

This legal system of racial classification based on patrilineal descent had no parallel anywhere in the Spanish-ruled territories in the Americas. In general, a son born of a sangley male and an indio or mestizo de sangley female was classified as mestizo de sangley; all subsequent male descendants were mestizos de sangley regardless of whether they married an India or a mestiza de sangley. A daughter born in such a manner, however, acquired the legal classification of her husband, i.e., she became an India if she married an indio but remained a mestiza de sangley if she married a mestizo de sangley or a sangley. In this way, a chino mestizo male descendant of a paternal sangley ancestor never lost his legal status as a mestizo de sangley no matter how little percentage of Chinese blood he had in his veins or how many generations had passed since his first Chinese ancestor; he was thus a mestizo de sangley in perpetuity.

However, a 'mestiza de sangley' who married a blanco ('Filipino', 'mestizo de español', 'peninsular' or 'americano') kept her status as 'mestiza de sangley'. But her children were classified as tornatrás. An 'India' who married a blanco also kept her status as India, but her children were classified as mestizo de español. A mestiza de español who married another blanco would keep her status as mestiza, but her status will never change from mestiza de español if she married a mestizo de español, Filipino or peninsular. In contrast, a mestizo (de sangley or español) man's status stayed the same regardless of whom he married. If a mestizo (de sangley or español) married a filipina (woman of pure Spanish descent), she would lose her status as a 'filipina' and would acquire the legal status of her husband and become a mestiza de español or sangley. If a 'filipina' married an 'indio', her legal status would change to 'India', despite being of pure Spanish descent.

The de facto social stratification system based on class that continues to this day in the country had its beginnings in the Spanish area with a discriminating caste system.[167]

The Insulares, who already saw their distinct identity from the peninsulares adopted the term Filipino to refer to themselves. And among these Insulares Luis Rodriguez y Varela was the first to use it.[168] The use of the term was later adopted by the Spanish and Chinese mestizos or those born of mixed Chinese-indio or Spanish-indio descent. Late in the 19th century, José Rizal popularized the use of the term Filipino to refer to all those born in the Philippines, including the Indios.[169] When ordered to sign the notification of his death sentence, which described him as a Chinese mestizo, Rizal refused. He went to his death saying that he was indio puro.[170][169]

After the Philippines' independence from Spain in 1898 and the word Filipino "officially" became a nationality that includes the entire population of the Philippines regardless of racial ancestry, as per the Philippine nationality law and as described by Wenceslao Retana's Diccionario de filipinismos, where he defined Filipinos as follows,[69]

todos los nacidos en Filipinas sin distincion de origen ni de raza.

All those born in the Philippines without distinction of origin or race.

— Wenceslao E. Retaña, Diccionario De Filipinismos: Con La Revisión De Lo Que Al Respecto Lleva Publicado La Real Academia Española

-

Native Visayan Filipinos as illustrated in the Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas (1734)

-

A Spaniard and Criollo talking, while Natives are cockfight. Aetas also in the background. detail from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas(1734).

-

Qing dynasty painting. Depicting Luzon delegates from the late 1750s, visiting the Qianlong Emperor in the Forbidden city in Beijing.[171]

-

Depiction of the Luzon Filipinos in 1700s from the Chinese book Huang Qing Zhigong Tu 1769. The Chinese called them Lu Song whom they recognized as a prosperous and powerful "kingdom" under the Spanish Empire.

-

Filipino Dragoon horseback 1786

-

Inhabitants of Manila 1787 by Gaspard Duché de Vancy

-

Mestizos of Manila circa 1790s

-

A Filipino in 1820 by John Crawfurd

-

Spanish Mestizo Filipinos by Jean Mallat de Basilan 1800's

-

Damián Domingo, A mestizo de Sangley soldier and artist.

-

A Visayan native girl by Damian Domingo.

-

"Mestizo de luto" (A Native Filipino Mestizo) by José Honorato Lozano

-

Filomena Asunción de Villafranca by Justiniano Asunción

-

Native riding a horse by José Honorato Lozano

-

Filipina girl. 19th century

-

Cuadrillero by José Honorato Lozano

-

Domíngo Róxas, early 1800's

-

A Gobernadorcillo, mostly of Indio descent. Painting by José Honorato Lozano

-

Soledad Francia by Antonio Malantic 1876 Philippines

-

Vine Guard 1841

-

Filipinos cock fighting 19th century

-

Native Principalía

-

Infantry army unfiorm in the Philippines 1856

-

Ambrosio Bautista by Filipino painter Mariano Asuncion

-

Filipina woman 1859

-

lawyer Don Narciso Padilla circa 1950s.

-

Native woman riding a horse.

-

Minister of the Mayor of Manila 1830's

-

Severina Ocampo de Arroyo painting by Filipino painter Simon Flores y de la Rosa

-

Native arsenal carpenter of Cavite

-

Don Felipe Campomanes 1871

-

Native Filipino family

-

a Mestizo de Español family

Origins and genetic studies

[edit]

The aboriginal settlers of the Philippines were primarily Negrito groups. Negritos today comprise a small minority of the nation's overall population, and received significant geneflow from Austronesian groups, as well as an even earlier "Basal-East Asian" group, while the modern Austronesian-speaking majority population does not, or only marginally show evidence for admixture, and cluster closely with other East/Southeast Asian people.[173][174] There were also immigrations from Austroasiatic, Papuan, and South Asian peoples.[175]

The majority population of Filipinos are Austronesians, a linguistic and genetic group whose historical ties lay in Maritime Southeast Asia and southern East Asia, but through ancient migrations can be found as indigenous peoples stretching as far east as the Pacific Islands and as far west as Madagascar off the coast of Africa.[176][177] The current predominant theory on Austronesian expansion holds that Austronesians settled the Philippine islands through successive southward and eastward seaborne migrations from the Neolithic Austronesian populations of Taiwan.[178]

Other hypotheses have also been put forward based on linguistic, archeological, and genetic studies. These include an origin from mainland southern China (linking them to the Liangzhu culture and the Tapengkeng culture, later displaced or assimilated by the expansion of speakers of Sino-Tibetan languages);[179][180] an in situ origin from the Sundaland continental shelf prior to the sea level rise at the end of the last glacial period (c. 10,000 BC);[181][182] or a combination of the two (the Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network hypothesis) which advocates cultural diffusion rather than a series of linear migrations.[183]

Genetics

[edit]The results of a massive DNA study conducted by the National Geographic's, "The Genographic Project", based on genetic testings of 80,000 Filipino people by the National Geographic in 2008–2009, found that the average Filipino's genes are around 53% Southeast Asia and Oceania, 36% East Asian, 5% Southern European, 3% South Asian and 2% Native American.[184]

According to a genetic study done by the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Research Program on Genes, Environment, and Health (RPGEH), most self-identified Filipinos sampled, have "modest" amounts of European ancestry consistent with older admixture.[185]

Dental morphology

[edit]Dental morphology provides clues to prehistoric migration patterns of the Philippines, with Sinodont dental patterns occurring in East Asia, Central Asia, North Asia, and the Americas. Sundadont patterns occur in Southeast Asia as well as the bulk of Oceania.[186] Filipinos exhibit Sundadonty,[186][187] and are regarded as having a more generalised dental morphology and having a longer ancestry than its offspring, Sinodonty.

Historic reports

[edit]

Published in 1849, The Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos contains 141 pages of surnames with both Spanish and Hispanicized indigenous roots.

Authored by Spanish Governor-General Narciso Claveria y Zaldua and Domingo Abella, the catalog was created in response to the Decree of November 21, 1849, which gave every Filipino a surname from the book. The decree in the Philippines was created to fulfill a Spanish colonial decree that sought to address colonial subjects who did not have a last name. This explains why most Filipinos share the same surnames as many Hispanics today, without having Spanish ancestry.

Augustinian Friar, Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, in the 1800s, measured varying ratios of Spanish-Mestizos as percentages of the populations of the various provinces, with ranges such as: 19.5% of the population of Tondo (The most populous province), to Pampanga (13.7%), Cavite (13%) and Bulacan (10.8%) to as low as 5% in Cebu, and non-existent in the isolated provinces.[144][145] Overall the whole Philippines, even including the provinces with no Spanish settlement, as summed up, the average percentage of Spanish Filipino tributes amount to 5% of the total population.[144][145]

The book, "Intercolonial Intimacies Relinking Latin/o America to the Philippines, 1898–1964 By Paula C. Park" citing "Forzados y reclutas: los criollos novohispanos en Asia (1756-1808)" gave the number of later Mexican soldier-immigrants to the Philippines, pegging the number at 35,000 immigrants in the 1700s,[141] in a Philippine population which was only around 1.5 Million,[188] thus the Latin Americans, mainly Mexicans, formed 2.33% of the population.[189]

In relation to this, a population survey conducted by German ethnographer Fedor Jagor concluded that 1/3rd of Luzon which holds half of the Philippines' population had varying degrees of Spanish and Mexican ancestry.[190]

Meanwhile, according to older records held by the Senate of the Philippines, there were approximately 1.35 million ethnic (or pure) Chinese within the Philippine population, while Filipinos with any Chinese descent comprised 22.8 million people (20% of the population).[191]

Current immigration

[edit]Recent studies during 2015, record around 220,000 to 600,000 American citizens living in the country.[192] This increased to 750,000 Americans living in the Philippines by year 2025, forming 0.75% of the population.[193] There are also 250,000 Amerasians across Angeles City, Manila, Clark and Olongapo, forming 0.25% of the population.[194] Together, the total percentage of individuals who possess full or partial American descent form 1% of the total demographics of the Philippines.

Languages

[edit]

Austronesian languages have been spoken in the Philippines for thousands of years. According to a 2014 study by Mark Donohue of the Australian National University and Tim Denham of Monash University, there is no linguistic evidence for an orderly north-to-south dispersal of the Austronesian languages from Taiwan through the Philippines and into Island Southeast Asia (ISEA).[181] Many adopted words from Sanskrit and Tamil were incorporated during the strong wave of Indian (Hindu-Buddhist) cultural influence starting from the 5th century BC, in common with its Southeast Asian neighbors. Chinese languages were also commonly spoken among the traders of the archipelago. However, with the advent of Islam, Arabic and Persian soon came to supplant Sanskrit and Tamil as holy languages. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, Spanish was the official language of the country for the more than three centuries that the islands were governed through Mexico City on behalf of the Spanish Empire. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Spanish was the preferred language among Ilustrados and educated Filipinos in general. Significant disagreements exist, however, on the extent Spanish use beyond that. It has been argued that the Philippines were less hispanized than Canaries and America, with Spanish only being adopted by the ruling class involved in civil and judicial administration and culture. Spanish was the language of only approximately ten percent of the Philippine population when Spanish rule ended in 1898.[195] As a lingua franca or creole language of Filipinos, major languages of the country like Chavacano, Cebuano, Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Bikol, Hiligaynon, Waray-Waray, and Ilocano assimilated many different words and expressions from Castilian Spanish.

Chavacano is the only Spanish-based creole language in Asia. Its vocabulary is 90 percent Spanish, and the remaining 10 percent is a mixture of predominantly Portuguese, Hiligaynon, and some English. Chavacano is considered by the Instituto Cervantes to be a Spanish-based language.[196][failed verification]

In sharp contrast, another view is that the ratio of the population which spoke Spanish as their mother tongue in the last decade of Spanish rule was 10% or 14%.[197] An additional 60% is said to have spoken Spanish as a second language until World War II, but this is also disputed as to whether this percentage spoke "kitchen Spanish", which was used as marketplace lingua compared to those who were actual fluent Spanish speakers.[197]

In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced universal education, creating free public schooling in Spanish, yet it was never implemented, even before the advent of American annexation.[198] It was also the language of the Philippine Revolution, and the 1899 Malolos Constitution proclaimed it as the "official language" of the First Philippine Republic, albeit a temporary official language. Spanish continued to be the predominant lingua franca used in the islands by the elite class before and during the American colonial regime. Following the American occupation of the Philippines and the imposition of English, the overall use of Spanish declined gradually, especially after the 1940s.

According to Ethnologue, there are about 180 languages spoken in the Philippines.[199] The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines imposed the Filipino language[200][201] as the national language and designates it, along with the English language, as one of the official languages. Regional languages are designated as auxiliary official languages. The constitution also provides that Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.[202]

Other Philippine languages in the country with at least 1,000,000 native and indigenous speakers include Cebuano, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Central Bikol, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Chavacano (Spanish-based creole), Albay Bikol, Maranao, Maguindanao, Kinaray-a, Tausug, Surigaonon, Masbateño, Aklanon and Ibanag. The 28-letter modern Filipino alphabet, adopted in 1987, is the official writing system. In addition, each ethnicity's language has their own writing scripts and set of alphabets, many of which are no longer used.[203]

However, there has been a resurgence of these ancient scripts, and initiatives to push the government for standardization. The most prominent script, Baybayin, is a writing system native to the Philippines, with the word 'baybay' meaning "to spell" in Tagalog (Bielenberg, 2018). Due to Spanish colonization, this script was replaced with the Latin alphabet which became the standard of the Philippines. In recent times, there has been a large interest in revitalizing Baybayin, with scholars spreading awareness and education online, and artists interpreting this script into their work.[204]

Religion

[edit]

According to then National Statistics Office (NSO) as of 2010, over 92% of the population were Christians, with 80.6% professing Roman Catholicism.[205] The latter was introduced by the Spanish beginning in 1521, and during their more than 330-year colonization of the islands, they managed to convert a vast majority of Filipinos, resulting in the Philippines becoming the largest predominantly catholic country in Asia. There are also large groups of Protestant denominations, which either grew or were founded following the disestablishment of the Catholic Church during the American Colonial period. The homegrown Iglesia ni Cristo is currently the single largest church whose headquarters is in the Philippines, followed by United Church of Christ in the Philippines. The Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also known as the Aglipayan Church) was an earlier development, and is a national church directly resulting from the 1898 Philippine Revolution. Other Christian groups such as the Victory Church,[206] Eddie Villanueva-founded and led Jesus Is Lord Church, Jesus Miracle Crusade, Mormonism, Orthodoxy, and the Jehovah's Witnesses have a visible presence in the country.

The second largest religion in the country is Islam, estimated in 2014[update] to account for 5% to 8% of the population.[207] Islam in the Philippines is mostly concentrated in southwestern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago which, though part of the Philippines, are very close to the neighboring Islamic countries of Malaysia and Indonesia. The Muslims call themselves Moros, a Spanish word that refers to the Moors (albeit the two groups have little cultural connection other than Islam).

Historically, ancient Filipinos held animist religions that were influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism, which were brought by traders from neighbouring Asian states. These indigenous Philippine folk religions continue to be present among the populace, with some communities, such as the Aeta, Igorot, and Lumad, having some strong adherents and some who mix beliefs originating from the indigenous religions with beliefs from Christianity or Islam.[208][209] There are temples also for Sikhism, also located in the provinces and in the cities, sometimes located near Hindu temples.[210]

As of 2013[update], religious groups together constituting less than five percent of the population included Sikhism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Seventh-day Adventists, United Church of Christ, United Methodists, the Episcopal Church in the Philippines, Assemblies of God, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), and Philippine (Southern) Baptists; and the following domestically established churches: Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ), Philippine Independent Church (Aglipayan), Members Church of God International, Jesus Is Lord Church, and The Kingdom of Jesus Christ, the Name Above Every Name. In addition, there are Lumad, who are indigenous peoples of various animistic and syncretic religions.[211]

Diaspora

[edit]

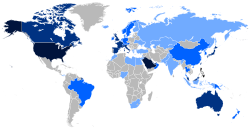

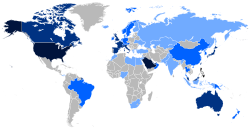

There are currently more than 10 million Filipinos who live overseas. Filipinos form a minority ethnic group in the Americas, Europe, Oceania,[212][213] the Middle East, and other regions of the world.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines.[214] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, immigrants from the Philippines made up the second largest group after Mexico that sought family reunification.[215]

Filipinos make up over a third of the entire population of the Northern Marianas Islands, an American territory in the North Pacific Ocean, and a large proportion of the populations of Guam, Palau, the British Indian Ocean Territory, and Sabah.[213][failed verification]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Including others such as Latin-Americans and Chinese-Mestizos, pure Chinese paid tribute but were not Philippine citizens as they were transients who returned to China, and Spaniards were exempt

References

[edit]- ^ Times, Asia (September 2, 2019). "Asia Times | Duterte's 'golden age' comes into clearer view | Article". Asia Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Remittances from Filipinos abroad reach 2.9 bln USD in August 2019 – Xinhua | English.news.cn". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019.

- ^ "ASIAN ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH ONE OR MORE OTHER RACES, AND WITH ONE OR MORE ASIAN CATEGORIES FOR SELECTED GROUPS". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Statistics Canada (November 15, 2023). "Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2021 Census – 25% Sample data". Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ "Distribution on Filipinos Overseas". Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "Know Your Diaspora: United Arab Emirates". Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "2021 Census QuickStats: Australia". censusdata.abs.gov.au.

- ^ "令和6年12月末現在における在留外国人数について". Retrieved April 3, 2025.

- ^ "No foreign workers' layoffs in Malaysia – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". February 9, 2009. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ https://www.paci.gov.kw/stat/StatIndicators.aspx[permanent dead link]

- ^ Davies Krish (April 9, 2019). "Qatar Population and Expat Nationalities". OnlineQatar. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Nicolas, Jino (June 24, 2018). "Economic diplomacy is as important as OFW diplomacy". BusinessWorld Online. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Overview of Philippines-Singapore Relations, Philippines: The Embassy Of The Philippines, November 14, 2018, archived from the original on March 1, 2023, retrieved March 2, 2023

- ^ Gostoli, Ylenia. "Coronavirus: Filipino front-line workers pay ultimate price in UK". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "2021.12Foreign Residents by Nationality" (ods) (in Chinese). National Immigration Agency, Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan. January 25, 2021. Archived from the original on October 19, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

資料截止日期:2021年11月30日 J95:K95 (PHILIPPINES) Male 58,229 Female 88,663

(immigration.gov.tw list of statistics Archived October 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine – 2021.12Foreign Residents by Nationality Archived October 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine) - ^ Filipinos in Hong Kong Archived June 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Hong Kong Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights – updated 30-04-20". Stats NZ. April 30, 2020. Table 5: Ethnic group (total responses). Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ "Demographic Balance and Resident Population by sex and citizenship on 31st December 2017". Istat.it. June 13, 2018. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Filipinos in South Korea Archived January 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Korean Culture and Information Service (KOIS). Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ "Das bedeutet der Besuch des philippinischen Präsidenten Marcos Jr. für Deutschland". Friedrich Naumann Stiftung. March 11, 2024.

- ^ "Les nouveaux Misérables: the lives of Filipina workers in the playground of the rich". The Guardian. October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2021. (cites data from Commission on Filipinos Overseas Stock estimate of overseans Filipinos As of December 2013 (xlsx) Archived February 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Overview of RP-Bahrain Relations". Republic of The Philippines; Embassy of The Philippines; Manama, Bahrain. (in English and Filipino). July 19, 2021. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Immigrants in Brazil (2024, in Portuguese)

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents" (in Norwegian). Retrieved July 9, 2025.

- ^ "Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics". Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Population; sex, age, generation and migration background, 1 January". Statline.cbs.nl. September 17, 2021. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Amojelar, Darwin G. (April 26, 2013) Papua New Guinea thumbs down Philippine request for additional flights Archived April 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. InterAksyon.com. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "Wachtregister asiel 2012–2021". npdata.be. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ "Macau Population Census". Census Bureau of Macau. May 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "National statistics of Denmark". statistikbanken.dk. August 11, 2025. Retrieved August 22, 2025.

- ^ "pinoys-sweden-protest-impending-embassy-closure". ABS-CBN.com. February 29, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "CSO Emigration" (PDF). Census Office Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Statistic Austria". Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ "President Aquino to meet Filipino community in Beijing". Ang Kalatas-Australia. August 30, 2011. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ https://www.croatiaweek.com/croatia-issues-over-53000-work-permits-in-three-months/

- ^ "Backgrounder: Overseas Filipinos in Switzerland". Office of the Press Secretary. 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ^ "Labour Force Indicators by Sex, 2014- 2019". www.eso.ky. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "Philippines, Indonesia affirm strong decades-long partnership". philstar.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Welcome to Embassy of Kazakhstan in Malaysia Website Archived November 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Kazembassy.org.my. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Tan, Lesley (June 6, 2006). "A tale of two states". Cebu Daily News. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook of Greece 2009 & 2010" (PDF). Hellenic Statistical Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "11rv – Syntyperä ja taustamaa sukupuolen mukaan kunnittain, 1990–2018". Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "No Filipino casualty in Turkey quake – DFA". GMA News. August 3, 2010. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Manila and Moscow Inch Closer to Labour Agreement". May 6, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ People: Filipino Archived October 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Joshua Project

- ^ "The Philippines To Sign Agreement with Morocco to Protect Filipino workers". Morocco World News. March 29, 2014. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ "Filipinos in Iceland". Iceland Review. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Filipinos in Finland". Finnish-Philippine Society co-operates with the migrant organizations. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Foreign born population of Aruba" (PDF). Central Bureau Statistics Aruba.

- ^ "Table 1.10; Household Population by Religious Affiliation and by Sex; 2010" (PDF). 2015 Philippine Statistical Yearbook: 1–30. October 2015. ISSN 0118-1564. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ^ "The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. Preamble. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

We, the sovereign Filipino people, ...

- ^ "Do People In The Philippines Speak Spanish? (Not Quite)". www.mezzoguild.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "Filipino". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scott, William Henry (1994). "Introduction". Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4. OCLC 32930303.

- ^ Cruz, Elfren S. (July 29, 2018). "From indio to Filipino". PhilStar Global. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Seijas, Tatiana, Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico (2014), Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. June 23, 2014. ISBN 978-1-107-06312-9. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. June 23, 2014. ISBN 978-1-107-06312-9. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Jubair, Salah (1997). A nation under endless tyranny. Islamic Research Academy. p. 10. OCLC 223003865.

- ^ a b c Aguilar, Filomeno V. (2005). "Tracing Origins: "Ilustrado" Nationalism and the Racial Science of Migration Waves". The Journal of Asian Studies. 64 (3): 605–637. doi:10.1017/S002191180500152X. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 25075827. S2CID 162939450.

- ^ Larousse, William (2001). A local church living for dialogue: Muslim-Christian relations in Mindanao-Sulu (Philippines), 1965–2000. Ed. Pont. Univ. Gregoriana. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-88-7652-879-8. OCLC 615447903.

- ^ Pedro Chirino (1604). Relacion de las islas Filippinas i de lo que in ellas an trabaiado los padres dae la Compania de Iesus. Del p. Pedro Chirino . por Estevan Paulino. pp. 38, 39, 52, 69. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Chirino, Pedro (1604). "Cap. XXIII". Relacion de las islas Filippinas i de lo que in ellas an trabaiado los padres dae la Compania de Iesus. Del p. Pedro Chirino . (in Spanish). por Estevan Paulino. p. 75. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

La primera i ultima diligencia que los Filipinos usavan en caso de enfermedad era, como avemos dicho, ofrecer algunos sacrificios a sus Anitos, o Diuatas, que eran sus dioses.

- ^ a b Kramer, Paul A. (2006). The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. University of North Carolina Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-8078-7717-3. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ H. Micheal Tarver Ph.D.; Emily Slape (2016), The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, pp. 217–219, ISBN 978-1-61069-422-3, archived from the original on February 18, 2023, retrieved February 29, 2020

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (1995). Bonifacio's bolo. Anvil Pub. p. 21. ISBN 978-971-27-0418-5. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Luis H. Francia (2013). "3. From Indio to Filipino : Emergence of a Nation, 1863-1898". History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. ABRAMS. ISBN 978-1-4683-1545-5. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Rolando M Gripaldo (2001). "Filipino Philosophy: A Critical Bibliography (1774–1997)". De la Salle University Press (E-book): 16 (note 1). Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Retaña, Wenceslao E. (1921). Diccionario de filipinismos, con la revisión de lo que al respecto lleva publicado la Real academia española. New York: Wentworth Press. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen (1915). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898: Relating to China and the Chinese. Vol. 23. A.H. Clark Company. pp. 85–87. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "'Filipinx,' 'Pinxy' among new nonbinary words in online dictionary". September 7, 2020. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ "Leave the Filipinx Kids Alone". September 7, 2020. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ "Filipino or Filipinx?". September 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Welch, Michael Patrick (October 27, 2014). "NOLA Filipino History Stretches for Centuries". New Orleans & Me. New Orleans: WWNO. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Aguilar, Filomeno V. (November 2012). "Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm". Journal of Global History. 7 (3): 364–388. doi:10.1017/S1740022812000241.

- ^ Catholic Church. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (December 2001). Asian and Pacific Presence: Harmony in Faith. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57455-449-6. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Pang, Valerie Ooka; Cheng, Li-Rong Lilly (1999). Struggling to be heard: the Unmet Needs of Asian Pacific American Children. NetLibrary, Inc. p. 287. ISBN 0-585-07571-9. OCLC 1053003694. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Holt, Thomas Cleveland; Green, Laurie B.; Wilson, Charles Reagan (October 21, 2013). "Pacific Worlds and the South". The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Race. Vol. 24. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4696-0724-5. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Westbrook, Laura. "Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana". Folklife in Louisiana. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "Re-imagining Australia – Voices of Indigenous Australians of Filipino Descent". Western Australian Museum. Government of Western Australia. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Ruiz-Wall, Deborah; Choo, Christine (2016). Re-imagining Australia: Voices of Indigenous Australians of Filipino Descent. Keeaira Press. ISBN 978-0-9923241-5-5.

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (April 12, 2018). "Latin America's lost histories revealed in modern DNA". Science. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Seijas, Tatiana (2014). Asian slaves in colonial Mexico: from chinos to Indians. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-47784-1.

- ^ Détroit, Florent; Mijares, Armand Salvador; Corny, Julien; Daver, Guillaume; Zanolli, Clément; Dizon, Eusebio; Robles, Emil; Grün, Rainer; Piper, Philip J. (April 2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines" (PDF). Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. hdl:10072/386785. PMID 30971845. S2CID 106411053. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Henderson, Barney (August 3, 2010). "Archaeologists unearth 67000-year-old human bone in Philippines". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012.

- ^ Scott 1984, pp. 14–15

- ^ "The Tabon Cave Complex and all of Lipuun". UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Tentative Lists. UNESCO. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Détroit, Florent; Corny, Julien; Dizon, Eusebio Z.; Mijares, Armand S. (June 2013). ""Small Size" in the Philippine Human Fossil Record: Is it Meaningful for a Better Understanding of the Evolutionary History of the Negritos?". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 45–66. doi:10.3378/027.085.0303. PMID 24297220. S2CID 24057857. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.