Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crime mapping

View on Wikipedia

| Criminology |

|---|

|

| Main Theories |

| Methods |

| Subfields and other major theories |

| Browse |

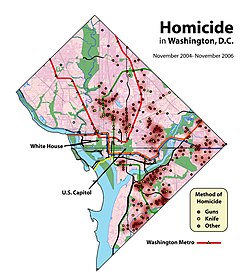

Crime mapping is used by analysts in law enforcement agencies to map, visualize, and analyze crime incident patterns. It is a key component of crime analysis and the CompStat policing strategy. Mapping crime, using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), allows crime analysts to identify crime hot spots, along with other trends and patterns.

Overview

[edit]Using GIS, crime analysts can overlay other datasets such as census demographics, locations of pawn shops, schools, etc., to better understand the underlying causes of crime and help law enforcement administrators to devise strategies to deal with the problem. GIS is also useful for law enforcement operations, such as allocating police officers and dispatching to emergencies.[1]

Underlying theories that help explain spatial behavior of criminals include environmental criminology, which was devised in the 1980s by Patricia and Paul Brantingham,[2] routine activity theory, developed by Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson and originally published in 1979,[3] and rational choice theory, developed by Ronald V. Clarke and Derek Cornish, originally published in 1986.[4] In recent years, crime mapping and analysis has incorporated spatial data analysis techniques that add statistical rigor and address inherent limitations of spatial data, including spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity. Spatial data analysis helps one analyze crime data and better understand why and not just where crime is occurring.

Research into computer-based crime mapping started in 1986, when the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) funded a project in the Chicago Police Department to explore crime mapping as an adjunct to community policing. That project was carried out by the CPD in conjunction with the Chicago Alliance for Neighborhood Safety, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Northwestern University, reported on in the book, Mapping Crime in Its Community Setting: Event Geography Analysis.[5] The success of this project prompted NIJ to initiate the Drug Market Analysis Program (with the appropriate acronym D-MAP) in five cities, and the techniques these efforts developed led to the spread of crime mapping throughout the US and elsewhere, including the New York City Police Department's CompStat.

Applications

[edit]Crime analysts use crime mapping and analysis to help law enforcement management (e.g. the police chief) to make better decisions, target resources, and formulate strategies, as well as for tactical analysis (e.g. crime forecasting, geographic profiling). New York City does this through the CompStat approach, though that way of thinking deals more with the short term. There are other, related approaches with terms including Information-led policing, Intelligence-led policing, Problem-oriented policing, and Community policing. In some law enforcement agencies, crime analysts work in civilian positions, while in other agencies, crime analysts are sworn officers.

From a research and policy perspective, crime mapping is used to understand patterns of incarceration and recidivism, help target resources and programs, evaluate crime prevention or crime reduction programs (e.g. Project Safe Neighborhoods, Weed & Seed and as proposed in Fixing Broken Windows[6]), and further understanding of causes of crime.

See also

[edit]Programs and projects

[edit]- CrimeView

- Criminal Reduction Utilising Statistical History

- CrimeAnalyst

- RAIDS Online

- RiskAhead

- ATACRAIDS

Individuals

[edit]Public access

[edit]- RAIDS Online

- SpotCrime.com

- Trulia, US real estate site with crime mapping

- YourMapper, open data crime mapping

- CitySafe, crime mapping for travelers & tourists

General

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ esri. "Crime Analysis: GIS Solutions for Intelligence-Led Policing" (PDF). esri.com.

- ^ Brantingham, Paul J.; Brantingham, Patricia L., eds. (1981). Environmental Criminology. Waveland Press. ISBN 978-0-88133-539-2.

- ^ Cohen, Lawrence E.; Felson, Marcus (1979). "Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach". American Sociological Review. 44 (4): 588–607. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.3696. doi:10.2307/2094589. JSTOR 2094589.

- ^ Cornish, Derek; Clarke, Ronald V. (1986). The Reasoning Criminal. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-96272-4.

- ^ Maltz, Michael D.; Gordon, Andrew C.; Friedman, Warren (2000) [1990]. Mapping Crime in Its Community Setting: Event Geography Analysis (PDF) (Internet ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97381-4.

- ^ Kelling, George; Coles, Catherine (1997) [1996]. Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83738-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Chainey, Spencer, Jerry Ratcliffe (2005). GIS and Crime Mapping. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-86099-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)