Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dongfeng (missile)

View on Wikipedia

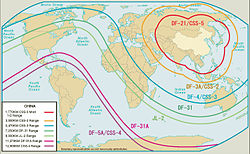

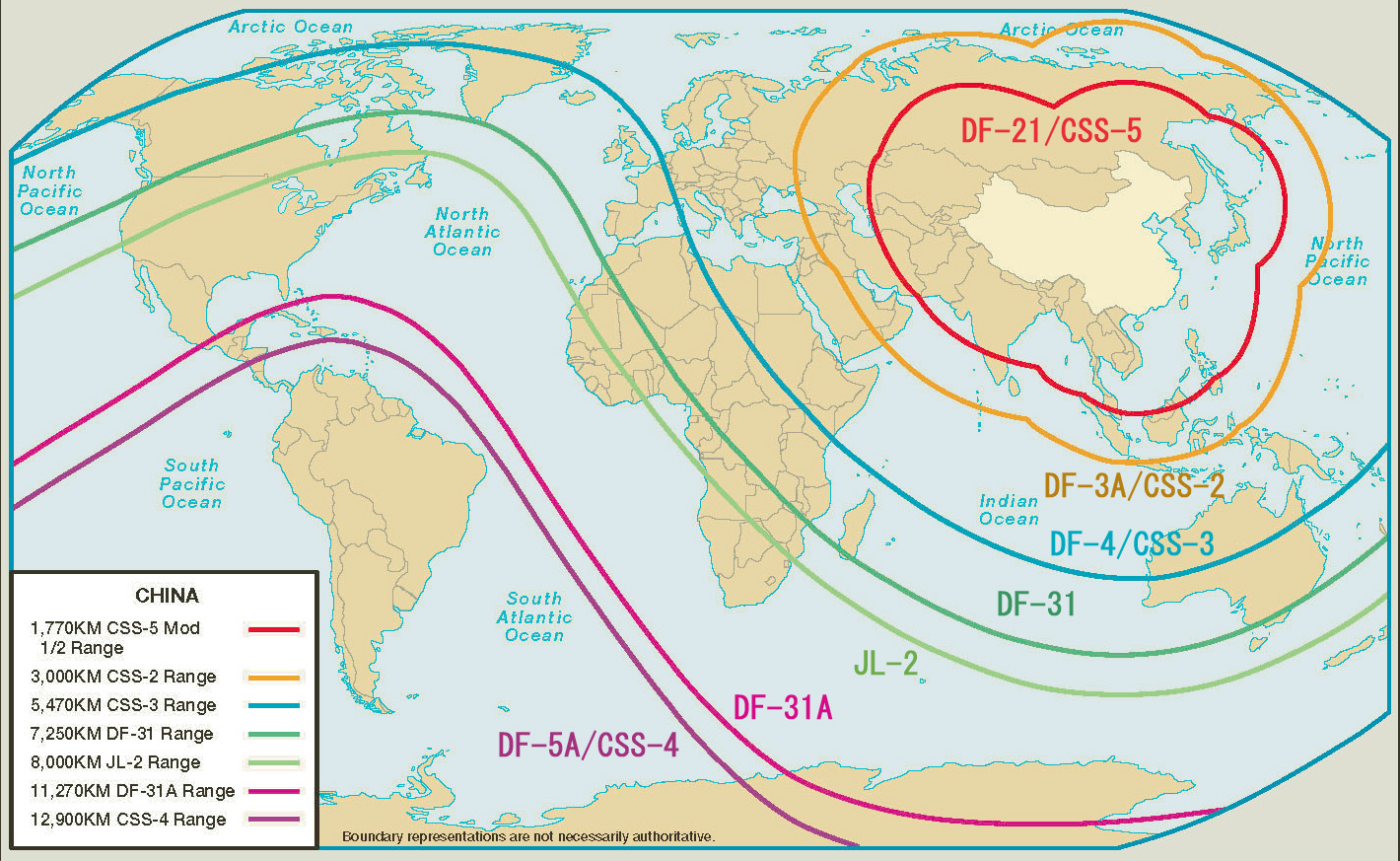

The Dongfeng (Chinese: 东风; lit. 'East Wind') series, typically abbreviated as "DF missiles", are a family of short, medium, intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missiles operated by the Chinese People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (formerly the Second Artillery Corps).

History

[edit]After the signing of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance in 1950, the Soviet Union assisted China's military R&D with training, technical documentation, manufacturing-equipment and licensed production of Soviet weapons. In the area of ballistic missiles, the Soviets transferred R-1 (SS-1), R-2 (SS-2) and R-11F technology to China.[1] The PRC based its first ballistic missiles on Soviet designs. Since then, China has made many advances in its ballistic-missile and rocket technology. For instance, the space-launch Long March rockets have their roots in the Dongfeng missiles.

Dongfeng missiles

[edit]

Dongfeng 1 (SS-2)

[edit]The first of the Dongfeng missiles, the DF-1 (SS-2, codenamed '1059', initially 'DF-1' , later the DF-3[1]), was a licensed copy of the Soviet R-2 (SS-2 Sibling) short-range ballistic missile (SRBM),[2] based on the German V-2 rocket. The DF-1 had a single RD-101 rocket engine, and used alcohol for fuel with liquid oxygen (LOX) as an oxidizer. The missile had maximum range of 550 km and a 500 kg payload. Limited numbers of DF-1 were produced in the 1960s, and have since been retired.[1]

Dongfeng 2 (CSS-1)

[edit]

The DF-2 (CSS-1) is China's first medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), with a 1,250 km range and a 15-20 kt nuclear warhead. It received the western designation of CSS-1 (stands for "China Surface-to-Surface").[3] It was long noted by western observers that the DF-2 could be a copy of the Soviet R-5 Pobeda (SS-3 Shyster), as they have identical look, range, engine and payload. The entire documentation for R-5 had been delivered from Soviet Union to China in the late 1950s.[4][unreliable source?] But some western authors still attribute the design to Chinese specialists Xie Guangxuan, Liang Sili, Liu Chuanru, Liu Yuan, Lin Shuang, and Ren Xinmin. The first DF-2 failed in its launch test in 1962, leading to the improved DF-2A. The DF-2A was used to carry out China's test of a live warhead on a rocket on 27 October 1966 (detonated in the atmosphere above Lop Nor), and was in operational service from the late 1960s. All DF-2 were retired from active duty in the 1980s.[5]

Dongfeng 3 (CSS-2)

[edit]The DF-3 (CSS-2) is often considered China's first "domestic" intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM). The common ICBM design was greatly influenced by the Soviet R-14 Chusovaya missile and the first stage engine itself was a direct copy of the С.2.1100/С.2.1150 La-350 booster engine developed by Aleksei Isaev at OKB-2 (NII-88). Design leadership has been attributed to both Tu Shou'e and Sun Jiadong. The missile was produced at Factory 211 (Capital Astronautics Co., [首都航天机械公司], also known as Capital Machine Shop, [首都机械厂]). The 2,500 km DF-3 was originally designed with a 2,000 kg payload to carry an atomic (later thermonuclear) warhead. A further improved DF-3A with 3,000 km range (~4,000 km with reduced payload) was developed in 1981, and exported to Saudi Arabia with a conventional high-explosive warhead.[6] The DF-3's range of 2,810 km means it is just short of being able to target Guam, although the 2012 DOD report on China's military power states that they have a range of 3,300 km, which would be enough to target Guam.[7] The 2013 Pentagon report on China's military power confirms the DF-3's 3,300 km range, and its maps show Guam being within the DF-3's range.[8] All DF-3/DF-3A's were retired by the mid-2010s and replaced by the DF-21.[9]

Dongfeng 4 (CSS-3)

[edit]The DF-4 (CSS-3) "Chingyu" is China's first two-stage ballistic missile, with 5,550-7,000 km range and 2,200 kg payload (3 Mt nuclear warhead). It was developed in late 1960s to provide strike capability against Moscow and Guam. The DF-4 missile also served as basis for China's first space launch vehicle, Chang Zheng 1 (Long March 1). Approx. 20 DF-4's remain in service, and are scheduled to be replaced by DF-31 by 2010–2015.[10][11]

Dongfeng 5 (CSS-4)

[edit]The DF-5 (CSS-4) is an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), designed to carry a 3 megaton (Mt) nuclear warhead to distance up to 12,000 km. The DF-5 is a silo-based, two-stage missile, and its rocket served as the basis for the space-launch vehicle Fengbao-Tempest (FB-1) used to launch satellites. The missile was developed in the 1960s, but did not enter service until 1981. An improved variant, the DF-5A, was produced in the mid 1990s with improved range (>13,000 km). Currently, an estimated 24-36 DF-5A's are in service as China's primary ICBM force. If the DF-5A is launched from the eastern part of the Qinghai province, it can reach cities like Los Angeles, Sacramento and San Francisco. If it is launched from the most eastern parts of northeastern provinces, it can cover all of the mainland of the United States.

Dongfeng 11 (CSS-7)

[edit]

The DF-11 (CSS-7, also M-11 for export), is a road-mobile SRBM designed by Wang Zhenhua at the Sanjiang Missile Corporation (also known as the 066 Base) in the late 1970s. Unlike previous Chinese ballistic missiles, the DF-11 use solid fuel, which greatly reduces launch preparation time to around 15–30 minutes, while liquid-fuelled missiles such as the DF-5 require up to 2 hours of pre-launch preparation. The DF-11 has a range of 300 km and an 800 kg payload. An improved DF-11A version has increased range of >825 km.[12] The range of the M-11 does not violate the limits set by the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). Estimates on the number of DF-11s in service vary between 500 and 600.[13][14]

Dongfeng 12 (CSS-X-15)

[edit]The DF-12 (CSS-X-15) is an SRBM formerly known as the M20. The change in designation signalled a shift in fielding to the Second Artillery Corps, making it possible the missile could be armed with a tactical nuclear warhead. Images of it bear a resemblance to the Russian 9K720 Iskander missile which, although not purchased by China from Russia, could have been acquired from former Soviet states. Like the Iskander, the DF-12 reportedly has built-in countermeasures including terminal maneuverability to survive against missile defense systems. Range is officially between 100–280 km (62–174 mi),[15] but given MTCR restrictions, actual maximum range may be up to 400–420 km (250–260 mi). With guidance provided by inertial navigation and Beidou, accuracy is 30 meters CEP; since the missile is controlled throughout the entire flight path, it can be re-targeted mid-flight. The DF-12 is 7.815 m (25.64 ft) long, 0.75 m (2.5 ft) in diameter, has a take-off weight of 4,010 kg (8,840 lb), and an 880 lb (400 kg) warhead that can deliver cluster, high explosive fragmentation, penetration, or high-explosive incendiary payloads. They are fired from an 8×8 transporter erector launcher (TEL) that holds two missiles.[16][17][18]

An anti-ship ballistic missile export variant of the M20, called A/MGG-20B (M20B), was unveiled at the 2018 Zhuhai Airshow.[19]

Dongfeng 15 (CSS-6)

[edit]

The DF-15 (CSS-6, also M-9 for export) was developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC, previously known as the 5th Aerospace Academy)'s Academy of Rocket Motor Technology (ARMT, also known as the 4th Academy). The missile is a single-stage, solid-fuel SRBM with a 600 km range and a 500 kg payload. During the 1995-1996 Taiwan strait crisis, the PLA launched six DF-15's near Taiwan in a demonstration of the missile's capability. Although the DF-15 is marketed for export, its range would violate the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) agreement, and thus no DF-15 has been exported to date. Approximately 300-350 DF-15's are in service with the PLA Rocket Force.[20][21]

Dongfeng 16 (CSS-11)

[edit]

The DF-16 (CSS-11)[22] is a new-model missile that has a longer range than the DF-15 (between 800–1,000 km (500–620 mi)). A Taiwan official announced on 16 March 2011 that Taiwan believed China had begun deploying the missiles.[23] The DF-16 represents an increased threat to Taiwan because it is more difficult to intercept for anti-ballistic missiles systems such as the MIM-104 Patriot PAC-3. Due to its increased range, the missile has to climb to higher altitudes before descending, giving more time for gravity to accelerate it on re-entry, faster than a PAC-3 could effectively engage it.[24] The DF-16 is an MRBM longer and wider than previous models with a 1,000–1,500 kg (2,200–3,300 lb) warhead and 5-10 meter accuracy. Its bi-conic warhead structure leaves room for potential growth to include specialized terminally guided and deep penetrating warheads. It is launched from a 10×10 wheeled TEL similar to that of the DF-21, but instead of a "cold launch" missile storage tube it uses a new protective "shell" to cover the missile.[25][26] Nuclear capable.[27]

The missile was shown to the public during the 2015 China Victory Day Parade in Beijing celebrating 70-year anniversary of the end of World War II.[28][29][30][31]

Dongfeng 17

[edit]The DF-17 is a medium-range ballistic missile used to launch the DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle.[32] The DF-ZF is a conventional warhead,[33] although US intelligence considers it to be nuclear capable as well.[34] The system entered service in the second half of 2019.[35]

Dongfeng 21 (CSS-5)

[edit]

The DF-21 (CSS-5) is a two-stage, solid-fuel MRBM developed by the 2nd Aerospace Academy (now China Changfeng Mechanics and Electronics Technology Academy) in late 1970s. It was the first solid-fuelled ballistic missile deployed by the Second Artillery Corp. The missile carries a single 500 kt nuclear warhead, with up to 2,500 km (1,600 mi) range. The DF-21 also served as the basis for the submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) JL-1 (CSS-N-3),[36] used on the Xia-class SSBN. In 1996, an improved variant, the DF-21A, was introduced. As of 2010, 60-80 DF-21/DF-21A were estimated to be in service; this number may have increased since then.[37][38] Sources say Saudi Arabia bought a DF-21 in 2007.

The latest variant, the DF-21D, has a maximum range exceeding 1,450 kilometres (900 mi; 780 nmi) according to the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center. It is hailed as the world's first anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) system, capable of targeting a moving carrier strike group from long-range, land-based mobile launchers. The DF-21D is thought to employ maneuverable reentry vehicles (MaRVs) with a terminal guidance system. It may have been tested in 2005–2006, and the launch of the Jianbing-5/YaoGan-1 and Jianbing-6/YaoGan-2 satellites offering targeting information from synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and visual imaging respectively.

Dongfeng 25

[edit]The DF-25 was a mobile-launch, two-stage, solid-fuel IRBM with a range of 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi). Development was allegedly cancelled in 1996.[39] The U.S. Department of Defense in its 2013 report to Congress on China's military developments made no mention of the DF-25 as a missile in service.[40]

Dongfeng 26 (CSS-18)

[edit]

The DF-26C is an IRBM with a range of at least 5,000 km (3,100 mi), far enough to reach U.S. naval bases in Guam. Few details are known, but it is believed to be solid-fuelled and road-mobile, allowing it to be stored in underground bunkers and fired at short notice, hence difficult to counter. It is possible that the DF-26C is a follow-up version of the DF-21. Possible warheads include conventional, nuclear or even maneuverable anti-ship and hypersonic glide warheads.[41]

Dongfeng 27

[edit]The DF-27 (CH-SS-X-24) is an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) equipped with a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) warhead.[42] The ballistic missile was in development as of 2021, with a range of 5,000 km to 8,000 km.[43]

Dongfeng 31 (CSS-10)

[edit]

The DF-31 (CSS-10) is a solid-fuel ICBM developed by China's 4th Aerospace Academy (now ARMT). The DF-31 has range of 8,000+ km, and can carry a single 1,000 kt warhead, or up to three 20-150 kt MIRV warheads. An improved version, the DF-31A, has range of 11,000+ km, far enough to reach Los Angeles from Beijing. The DF-31 was developed to replace many of China's older ballistic missiles, and served as basis to the new JL-2 (CSS-NX-4/CSS-NX-5) SLBM. In 2009, approx. 30 DF-31/DF-31A are estimated to be in service; it is possible this number may have increased since then.[44][45] 12 were displayed at the 2009 military parade in Beijing commemorating the 60th anniversary of the PRC's founding.

The DF-31AG uses a mobile launcher with improved mobility. It made its first official public appearance in the 2017 PLA Day Parade.[46]

Dongfeng 41 (CSS-20)

[edit]The DF-41 (CSS-20) is a solid-fuel ICBM equipped to carry ten or twelve MIRV warheads. With an estimated range between 12,000 - 15,000 km, it is believed to surpass the range of the US's LGM-30 Minuteman ICBM to become the world's longest range missile.[47][48]

Dongfeng 61

[edit]The DF-61 is a solid-fuel ICBM and the newest addition to China's nuclear arsenal. It was first unveiled during the 2025 China Victory Day Parade.[49]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c DF-1 Archived 2017-07-31 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ R-2 / SS-2 SIBLING Archived 2021-03-23 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ DF-2 / CSS-1 Archived 2009-09-10 at the Wayback Machine GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ R-5 / SS-3 SHYSTER Archived 2018-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ DongFeng 2 (CSS-1) Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2011-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ [1] Archived 25 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2012" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2013" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ DongFeng 3 (CSS-2) Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2013-08-14 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ DF-4 (the "Chingyu" missile) Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ DongFeng 4 (CSS-3) Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ "DONG FENG - EAST WIND/JULANG - GREAT WAVE". softwar.net. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ DF-11 (CSS-7) Archived 2022-02-27 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ DongFeng 11 (CSS-7) Short-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2012-06-06 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2014). 2014 Report to Congress (PDF) (Report). pp. 315–316. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Cole, J. Michael (7 August 2013). "China's Second Artillery Has a New Missile". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11.

- ^ DF-12 / M20 Archived 2016-05-09 at the Wayback Machine - Globalsecurity.org.

- ^ DF-12 M20 short-range surface-to-surface tactical missile Archived 2016-10-17 at the Wayback Machine - Armyrecognition.com

- ^ East Pendulum [@HenriKenhmann] (10 November 2018). "| #AirshowChina 2018 | Contrairement à son concurrent CASIC, le groupe CASC n'a donné aucun détail sur ses deux nouveaux missiles balistiques M20A et M20B, variantes de M20. La version A semble être dotée d'une tête chercheuse hors radar, et la B est dédié à l'anti-navire. https://t.co/5jKOfKeTLC" [| #AirshowChina 2018 | Unlike its competitor CASIC, the CASC group gave no details on its two new ballistic missiles M20A and M20B, variants of M20. Version A seems to be equipped with an off-radar seeker, and version B is dedicated to anti-ship.] (Tweet) (in French). Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ DF-15 (CSS-6 / M-9) Archived 2006-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ DongFeng 15 (CSS-6) Short-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2006-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ "DF-16 / CSS-11 - China Missile Forces". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ Doug Richardson (2011-03-24). "China deploys DF-16 ballistic missile, claims Taiwan". Defense & Security Intelligence & Analysis: IHS Jane's. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ^ PRC missile could render PAC-3s obsolete Archived 2014-12-05 at the Wayback Machine - Taipeitimes.com, 18 March 2011

- ^ China's DF-16 Medium-range Ballistic Missile Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine - Aviationweek.com, 17 September 2012

- ^ CHINA'S NEWEST MISSILE SET FOR VJ DAY PARADE Archived 2015-10-24 at the Wayback Machine - Popsci.com, 28 April 2015

- ^ "DF-16 (Dong Feng-16 / CSS-11)". Missile Threat. Archived from the original on 2018-11-10. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ [2] [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Beijing's WWII military parade | China.org.cn Live – Live updates on top news stories and major events". Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ^ "YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13.

- ^ Fisher Jr, Richard D. "China showcases new weapon systems at 3 September parade". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ Nouwen et al. 2024, p. 10.

- ^ Mihal 2021, p. 22.

- ^ Panda, Ankit (16 February 2020). "Questions About China's DF-17 and a Nuclear Capability". The Diplomat. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Wood & Cliff 2020, p. 23.

- ^ JuLang 1 (CSS-N-3) Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile Archived 2006-05-10 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ DF-21 / CSS-5 Archived 2021-11-16 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ DongFeng 21 (CSS-5) Medium-Range Ballistic Missile Archived 2008-02-01 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ "DF-25". missilethreat.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2013 (PDF). Office of the Secretary of Defense (Report). U.S. Department of Defense. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Lowther, William (6 March 2014). "China developing new nuclear missile". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 2017-03-19.

- ^ Gwadera, Zuzanna (18 May 2023). "Intelligence leak reveals China's successful test of a new hypersonic missile". The International Institute for Strategic Studies.

- ^ Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2021 (PDF). Office of the Secretary of Defense (Report). U.S. Department of Defense. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ DF-31 Archived 2017-03-17 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ DongFeng 31A (CSS-9) Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Archived 2010-04-06 at the Wayback Machine Sinodefence.com

- ^ Nouwen 2018, p. 5.

- ^ "DF-41 (CSS-X-10)". missilethreat.com. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "DF-41". globalsecurity.org. 2014. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (2025-09-03). "China introduces new ICBM as part of "three-in-one" nuclear force". CNN. Reuters. Retrieved 2025-09-03.

Sources

[edit]- Nouwen, Veerle (2018). PLA Rocket Force Modernization and China's Military Reforms (Report). RAND. doi:10.7249/CT489.

- Mihal, Christopher J. (July–August 2021). "Understanding the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force". Military Review. 101 (4): 16–30.

- Nouwen, Veerle; Wright, Timothy; Graham, Euan; Herzinger, Blake (January 2024). Long-range Strike Capabilities in the Asia-Pacific: Implications for Regional Stability (Report). The International Institute for Strategic Studies.

- Wood, Peter; Cliff, Roger (2020). A Case Study of the PRC's Hypersonic Systems Development. China Aerospace Studies Institute. ISBN 9798672412085.

External links

[edit]- Lewis, John Wilson; Di, Hua (Fall 1992). "China's Ballistic Missile Programs: Technologies, Strategies, Goals". International Security. 17 (2): 5–40. doi:10.2307/2539167. JSTOR 2539167. S2CID 153900455. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Ballistic Missiles of China

Dongfeng (missile)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Nomenclature and Designations

The Dongfeng (Chinese: 东风; pinyin: Dōngfēng; lit. 'East Wind') designation refers to a family of ballistic missiles developed by China for the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force, encompassing short-range to intercontinental systems. Missiles in the series are abbreviated as DF-#, where "DF" derives from the pinyin transliteration of Dongfeng, and the numeral denotes the model variant in approximate order of development initiation rather than strict correlation to range, generation, or performance metrics. For instance, the DF-2 represents China's first domestically produced medium-range ballistic missile, while later designations like DF-41 indicate more advanced intercontinental systems.[7][8] Subvariants append letters to the base numeral to signify upgrades in propulsion, payload, accuracy, or mobility, though conventions are not rigidly standardized across all models. Examples include the DF-5A, an enhanced silo-based intercontinental missile with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) capability compared to the liquid-fueled DF-5; the DF-21D, a conventionally armed anti-ship variant of the solid-fueled DF-21; and the DF-31AG, featuring improved cross-country mobility over the road-mobile DF-31A. Such modifiers often reflect iterative improvements driven by technological advancements or operational requirements, with "A" typically indicating initial upgrades, "G" denoting high-mobility enhancements in some cases, and payload-specific adaptations like nuclear (e.g., DF-21A) versus conventional (e.g., DF-21C for land attack).[9][2][10] Western military and intelligence communities, including NATO, employ reporting names prefixed with CSS-# (Chinese Surface-to-Surface) followed by a sequential numeral for identification in assessments and doctrine, independent of Chinese numbering. These began with early systems like CSS-1 (DF-2) and progressed to CSS-10 (DF-31 family), aiding standardization without revealing classified details; for example, the DF-5 corresponds to CSS-4, and the DF-21 to CSS-5. The CSS system originated in Cold War-era conventions for non-Western threats and persists in U.S. Department of Defense reports for consistency in threat evaluation.[2][11][7]General Technical Characteristics

The Dongfeng missile family encompasses a range of ballistic missiles utilizing both liquid and solid propellants, with early designs like the DF-4 employing two-stage liquid-fueled propulsion for intermediate to intercontinental ranges, while subsequent models transitioned to solid propellants for improved storability, rapid launch preparation, and operational flexibility.[12][2] Modern solid-fueled variants, such as the DF-31 and DF-41, feature multi-stage configurations—typically three stages—to achieve intercontinental reach, enabling boosts to suborbital trajectories with payloads including nuclear or conventional warheads.[13][14] Guidance systems predominantly rely on inertial navigation for midcourse flight, providing autonomy against jamming, though advanced iterations incorporate satellite-assisted corrections via BeiDou or GPS equivalents for terminal-phase precision, yielding circular error probable (CEP) accuracies from tens of meters in legacy systems to as low as 5 meters in newer short- to medium-range models.[15][1] Some variants integrate terminal active radar or electro-optical seekers to counter missile defenses through evasive maneuvers or fine adjustments.[16] Warhead configurations vary by missile, supporting single warheads with yields up to several megatons in liquid-fueled ICBMs like the DF-5, or multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) in solid-fueled systems such as the DF-41, which can accommodate up to 10 warheads totaling 2,500 kg alongside penetration aids like decoys or chaff to overwhelm defenses.[9][14] Launch platforms emphasize mobility and survivability, with road-mobile transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) standard for most post-1990s designs to enable dispersal and reduce vulnerability to counterforce strikes, complemented by silo basing for select ICBMs.[2][17]Historical Development

Origins and Early Soviet Influence (1950s–1970s)

China's ballistic missile program originated in the mid-1950s amid efforts to build strategic capabilities, with initial progress dependent on Soviet technological transfers under bilateral agreements. In October 1956, the Soviet Union committed to aiding China's missile development, supplying technical documentation, training, and sample missiles including the R-1 (a copy of the German V-2) and R-2 short-range ballistic missiles.[18][19] The establishment of the Fifth Academy in 1956 centralized research, focusing on reverse-engineering Soviet designs with hundreds of engineers trained in the USSR.[20] Early tests demonstrated growing proficiency in Soviet-derived technology. China received two R-2 missiles in December 1957 and conducted its first static firing of a Chinese-built R-2 in June 1958, followed by a successful launch later that year.[4] By 1959, Soviet provision of R-11 (Scud-A) technical data enabled work on the Dongfeng-1 (DF-1), a licensed variant with a range of approximately 250 kilometers using liquid propulsion.[18][20] The DF-1's maiden flight occurred on November 5, 1960, just after the 1960 Sino-Soviet split severed ongoing cooperation, leaving China to rely on existing blueprints and hardware.[18][20] The rupture in Soviet aid accelerated indigenous efforts, though early designs retained foundational Soviet influences in propulsion and guidance. Development of the Dongfeng-2 (DF-2), China's first medium-range ballistic missile with a range exceeding 1,000 kilometers, commenced in the early 1960s using liquid-fueled engines adapted from prior technology.[21] Initial DF-2 tests launched in June 1964, with the system achieving operational deployment by 1966 despite technical challenges.[18][21] Into the 1970s, this base supported expansions like the DF-3, an improved inertial-guided variant tested from 1964 and fielded around 1971, marking a transition toward greater autonomy while underscoring the enduring impact of 1950s Soviet inputs on structural and subsystem designs.[18]Independence and Expansion Post-1979

Following the disruptions of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), which had stalled progress in missile development, China's Dongfeng program experienced renewed focus and expansion in the post-1979 era under Deng Xiaoping's emphasis on military modernization and technological self-sufficiency. On October 30, 1979, Marshal Nie Rongzhen, who had spearheaded early missile efforts, was reinstated to oversee defense science and technology, enabling recovery from prior setbacks and acceleration of indigenous projects free from foreign dependencies.[22] This period marked the operationalization of fully domestic designs, culminating in the deployment of the DF-5, China's inaugural intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), in 1981. Developed since 1966 using entirely internal resources, the two-stage, liquid-fueled DF-5 featured a range of approximately 13,000 kilometers, enabling strikes on targets throughout the continental United States from silo launchers in central China. Initial deployments involved a limited number of missiles—starting with two in hardened silos for improved survivability—reflecting a strategic shift toward a minimal but reliable nuclear deterrent capable of penetrating U.S. defenses.[9][23][24] Expansion extended to intermediate-range systems, with the DF-4 achieving operational status in the early 1980s, providing a range of about 5,500 kilometers for targeting Soviet and Asian sites from fixed sites. These liquid-fueled missiles prioritized range and payload over mobility, with production scaling to support a modest arsenal growth amid resource constraints. Silo construction and testing, including a key pre-deployment flight on December 7, 1981, from Taiyuan, underscored efforts to enhance second-strike reliability without external aid.[8][25] By the mid-1980s, these deployments had established China as self-reliant in strategic missile production, with the program emphasizing quantitative buildup and infrastructural hardening to counter perceived threats from superpowers, though vulnerabilities like lengthy fueling times persisted until solid-fuel transitions in subsequent decades.[8]Modern Advancements and Hypersonic Integration (1990s–Present)

Following the maturation of indigenous solid-propellant technology in the 1990s, China accelerated development of road-mobile ballistic missiles under the Dongfeng series, emphasizing survivability against preemptive strikes through mobility and reduced launch preparation times. The DF-31, China's first domestically developed solid-fueled intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), underwent its initial flight test in August 1999 but faced delays in guidance system procurement, entering service with the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force in 2006 with a range of approximately 7,000–8,000 kilometers.[13] This marked a shift from silo-based liquid-fueled systems to transporter-erector-launchers (TELs), enhancing second-strike capabilities amid growing concerns over U.S. missile defenses. Subsequent variants, such as the DF-31A (deployed around 2007) and DF-31B (around 2017), extended ranges to 11,000 kilometers and incorporated multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) for improved penetration.[13][26] The DF-41 further advanced this trajectory, featuring a three-stage solid-propellant design capable of ranges between 12,000 and 15,000 kilometers, with potential for up to 10 MIRVs or a mix of decoys and penetration aids. First publicly displayed in 2015 and entering operational deployment by 2017, the DF-41's 16-wheel TEL enables off-road mobility across China's vast interior, complicating adversary targeting.[14] These developments reflected iterative improvements in propulsion, materials, and inertial navigation, drawing on lessons from earlier Dongfeng iterations while prioritizing countermeasures to ballistic missile defenses, such as terminal-phase maneuvering.[14] Hypersonic integration emerged prominently in the 2010s, with the DF-17 representing a milestone in boost-glide technology paired with Dongfeng boosters. The DF-17, utilizing the DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV), achieved its first successful test in January 2014 following developmental flights, achieving speeds of Mach 5–10 and ranges of 1,800–2,500 kilometers through atmospheric maneuvering that evades traditional interceptors.[27] Deployed operationally by 2020, it integrates a solid-fueled ballistic missile first stage with a gliding warhead capable of unpredictable trajectories, enhancing precision strikes against fixed and mobile targets like aircraft carriers.[28] This system, road-mobile on TELs, underscores China's focus on asymmetric capabilities in regional contingencies, though U.S. assessments note challenges in sustained hypersonic flight and thermal management remain.[27] Further iterations, including potential air-launched variants, indicate ongoing refinement of hypersonic reentry vehicles across the Dongfeng lineage for both conventional and nuclear roles.[27]Ballistic Missile Variants by Range

Short-Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs)

The Dongfeng short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) comprise the DF-11, DF-15, and DF-16 series, providing the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) with mobile, solid-fueled systems for precise regional strikes, primarily conventional but with nuclear options, targeting operational areas such as the Taiwan Strait. These missiles emphasize road mobility, rapid deployment, and improved guidance to counter defenses in anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) scenarios.[29] The DF-11 (CSS-7), developed from 1984 and entering PLARF service in 1992, is a single-stage, solid-propellant SRBM measuring 7.5 m long, 0.8 m in diameter, and weighing 3,800 kg at launch. Its baseline range reaches 280-300 km with a 500-800 kg payload, accommodating high-explosive, submunition, fuel-air explosive, chemical, or nuclear warheads yielding 2-20 kt; circular error probable (CEP) stands at 600 m, though upgrades enhance this. The DF-11A variant, operational since 1999, extends range to 500-600 km and improves accuracy to 150-200 m CEP, potentially 20-30 m with terminal guidance, while the DF-11AZT adds earth-penetrating capability. Launched from WS-2400 transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) with about 30 minutes preparation, deployments include 700-750 missiles and 120-140 launchers as of 2009 estimates, concentrated at bases like Jiangshan and Meizhou near Taiwan; exports as M-11 occurred to Pakistan in 1992.[30][31] The DF-15 (CSS-6), a single-stage solid-fueled system operational since the early 1990s, spans 9.1 m in length, 1 m diameter, and 6,200 kg launch weight, achieving 600-800 km range with 500-800 kg warheads including high-explosive, nuclear (50-350 kt), chemical, or submunitions payloads. Road-mobile on eight-wheeled TELs, it supports vertical launch and variants like DF-15A/B/C integrate inertial and Beidou satellite navigation for precision against fixed and mobile targets, with some bunker-busting configurations. Deployed in significant numbers for theater suppression, it complements longer-range systems in PLARF brigades focused on regional contingencies.[32][1] The DF-16 (CSS-11), a two-stage solid-propellant advancement entering service around 2011-2012, delivers 800-1,000 km range via a 1.2 m diameter body and WS-2500 TELs, carrying 500-1,000 kg high-explosive or submunition warheads optimized for hardened and deeply buried targets. Developed by China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) in the 2000s to succeed DF-11/15 models, it features maneuvering reentry vehicles in Mod 1/2 variants for enhanced penetration; by 2021, approximately 36 launchers operated, including in Guangdong Province, supporting strikes on Taiwan and Southeast Asian sites.[33]Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs)

The Dongfeng-21 (DF-21, NATO: CSS-5) is a road-mobile, two-stage, solid-fueled medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) with a range of 1,700 to 2,800 kilometers, enabling strikes across regional theaters including parts of East Asia and the Western Pacific.[2][1] Developed by the Academy of Rocket Motor Technology and entering service around 1991, it marked China's shift toward mobile, survivable MRBMs capable of carrying nuclear or conventional warheads with payloads up to 600 kilograms.[34][2] Key variants include the baseline DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1), an inertial-guided system with a circular error probable (CEP) of about 300-400 meters; the DF-21A (Mod 2), incorporating satellite navigation for improved accuracy to under 100 meters CEP; and the DF-21B (Mod 3), featuring a maneuverable reentry vehicle for enhanced penetration of missile defenses.[2][35] The DF-21C (Mod 4) is a conventional land-attack variant with submunitions or unitary warheads for precision strikes, while the DF-21D (Mod 5), operational since around 2010, is an anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) designed to target moving naval assets like aircraft carriers using terminal guidance from satellites, over-the-horizon radar, and infrared seekers, with reported ranges up to 1,500-2,700 kilometers depending on payload.[2][36] The DF-21's transporter-erector-launcher (TEL) vehicles, typically 6x6 or 8x8 wheeled platforms, enhance survivability through rapid deployment and dispersal, supporting China's anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategy.[2] Deployment estimates suggest over 100 launchers and missiles in the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force inventory as of the mid-2010s, with production continuing amid upgrades for hypersonic elements in later iterations.[2] Earlier DF-2 (CSS-1), a liquid-fueled MRBM with 1,250-kilometer range introduced in the 1960s, served as a precursor but was phased out due to logistical vulnerabilities.[1]Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs)

The Dongfeng series includes the DF-3 as its early intermediate-range ballistic missile, developed during the Cold War era, and the modern DF-26, which forms the backbone of China's current IRBM capabilities. These missiles enable strikes against targets at distances of 3,000 to 5,500 kilometers, supporting both nuclear deterrence and conventional precision operations in the Asia-Pacific theater.[3][37] The DF-3, also known as CSS-2, was a liquid-fueled, single-stage missile that entered service in 1971 with a range of up to 4,000 kilometers when carrying a 2,000-kilogram payload. It featured inertial guidance and could deliver a nuclear warhead of approximately 3 megatons, primarily targeting regional adversaries like the Soviet Union. Production ceased in the 1980s, and all DF-3 units have been retired from active service by the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force as of the early 2000s, replaced by more advanced systems.[37] The DF-26, introduced operationally around 2015, is a two-stage, solid-fueled, road-mobile IRBM measuring 14 meters in length with a diameter of 1.4 meters and a launch weight of about 20,000 kilograms. It achieves a range of 3,000 to 5,000 kilometers, depending on payload, enabling it to reach U.S. bases in Guam from mainland China. Capable of carrying a 1,200 to 1,800 kilogram warhead—either nuclear or conventional—the missile supports both land-attack and anti-ship missions, with variants like the DF-26C optimized for maritime strikes against moving naval targets such as aircraft carriers. Guidance combines inertial systems with satellite and possibly terminal-phase sensors for circular error probable (CEP) accuracies estimated at 10 to 100 meters.[3][38][39] As of 2024, the PLA Rocket Force maintains an estimated 250 DF-26 launchers with around 500 missiles, reflecting significant expansion from initial deployments of about 16 launchers in 2018. This force has fully supplanted older dual-capable systems like certain DF-21 variants for intermediate-range roles, emphasizing mobility via transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) to enhance survivability against preemptive strikes. The DF-26's versatility underscores China's anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy, particularly in potential contingencies involving Taiwan or the South China Sea.[39][40]Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

![DF-31 ICBMs][float-right] The Dongfeng series includes several intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with ranges exceeding 5,500 kilometers, primarily developed to provide China with strategic nuclear deterrence capabilities. These systems encompass both silo-based liquid-fueled designs like the DF-5 and road-mobile solid-fueled variants such as the DF-31 and DF-41, reflecting advancements in propulsion, mobility, and payload delivery.[29][41] The DF-5, China's first domestically developed ICBM, is a two-stage, liquid-fueled missile deployed in silos since the early 1980s. It achieves a range of approximately 12,000 kilometers, sufficient to target much of the continental United States, and carries a payload of up to 3,900 kilograms, typically a single nuclear warhead with yields of 1 to 3 megatons. Upgraded variants, including the DF-5A with improved accuracy and the DF-5B capable of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), have extended its service life into the 21st century, though its lengthy preparation time—up to two hours—limits rapid response compared to solid-fuel systems.[9][42][24] The DF-31 family represents a shift to solid-propellant, three-stage, road-mobile ICBMs, with initial deployment around 2006. The baseline DF-31 has an estimated range of 7,000 to 8,000 kilometers, while the extended-range DF-31A reaches 11,200 kilometers, enabling coverage of most U.S. targets from Chinese territory. These missiles, transported on transporter-erector-launchers (TELs), enhance survivability through mobility and quick launch readiness, with payloads supporting single warheads or limited MIRVs in later models like the DF-31AG, which features an 8-axle TEL for improved off-road capability.[13][41][43] The DF-41, the most advanced Dongfeng ICBM, is a three-stage solid-fueled missile with a range of 12,000 to 15,000 kilometers, deployable from road-mobile TELs or rail platforms. Operational since the mid-2010s, it can carry up to 10 MIRV warheads, significantly increasing its target coverage and complicating missile defenses. Chinese media claims emphasize its high speed—up to Mach 25—and penetration aids, positioning it as a cornerstone of second-strike capability. Deployment estimates suggest dozens of launchers, often camouflaged for evasion.[14][44][45]Advanced and Hypersonic Variants

Hypersonic Glide Vehicles and Maneuverable Reentry Vehicles

The DF-17 (Dongfeng-17) represents China's primary operational integration of a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) within the Dongfeng ballistic missile family, utilizing a solid-fueled booster to launch the DF-ZF glider, which separates post-apogee to perform skipping maneuvers at altitudes of 20-100 km and speeds exceeding Mach 5. This boost-glide architecture enables quasi-ballistic trajectories that challenge interceptors by altering speed, altitude, and course during the glide phase, with estimated ranges of 1,800-2,500 km and potential for both conventional and nuclear payloads. The system enhances penetration against theater defenses, as the HGV's maneuverability reduces predictability compared to traditional reentry vehicles.[46] Development of the DF-17 traces to mid-2010s flight tests of the DF-ZF prototype, with operational deployment occurring by 2019, as evidenced by its unveiling during China's National Day parade on October 1, 2019. Subsequent evaluations, including 2021 assessments by U.S. intelligence, confirmed its road-mobile TEL (transporter-erector-launcher) configuration for rapid deployment and survivability. In September 2025, the DF-17 was prominently featured in a People's Liberation Army parade, underscoring its role in conventional precision strikes. Recent reports indicate expanded basing near Taiwan as of October 2025, signaling integration into regional anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) postures.[46][47][48] Maneuverable reentry vehicles (MaRVs) in Dongfeng variants, such as the DF-21D and DF-26, employ terminal-phase guidance—likely infrared seekers combined with inertial updates—to execute evasive maneuvers during atmospheric reentry, achieving effective speeds up to Mach 10 while adjusting for moving targets like aircraft carriers. The DF-21D, an anti-ship ballistic missile variant of the DF-21 MRBM, incorporates a MaRV warhead with a range exceeding 1,500 km, first tested in 2005-2006 to validate terminal homing against simulated naval assets. Operational since approximately 2010, it relies on over-the-horizon targeting data from satellites and radars for initial cueing.[49][2] The DF-26 IRBM extends MaRV capabilities to intermediate ranges of 3,000-5,000 km, with its anti-ship subvariant (DF-26B) featuring a maneuvering warhead for precision strikes on high-value maritime targets, including U.S. bases at Guam. Introduced around 2015 and publicly displayed in 2015 and 2019 parades, the DF-26 integrates dual conventional/nuclear roles, with MaRV maneuvers enhancing accuracy to circular error probable (CEP) estimates under 10 meters in terminal phase. The DF-27, a newer hypersonic system potentially blending HGV and MaRV elements, offers extended ranges of 5,000-8,000 km and flight-path maneuverability, entering service by 2022-2023 based on test data from 2019 onward. These MaRV-equipped Dongfeng missiles prioritize countering U.S. carrier strike groups, though real-world efficacy against defended targets remains unproven in combat and subject to electronic warfare vulnerabilities.[3][50]Anti-Ship and Dual-Capable Systems

The Dongfeng series features anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) tailored for precision strikes against naval targets, including aircraft carriers, as part of China's anti-access/area denial strategy in the Western Pacific. These systems integrate advanced terminal guidance and maneuverable reentry vehicles to engage moving ships at extended ranges, relying on satellite, radar, and over-the-horizon sensors for target acquisition.[49][51] The DF-21D, derived from the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile, represents the first operational ASBM, with a range exceeding 1,500 kilometers and terminal velocities reaching Mach 10. Its maneuverable warhead enables evasion of ship-based defenses, posing a direct threat to large surface combatants such as U.S. Navy carriers operating beyond 1,000 kilometers from China's coast. Deployed by the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force since approximately 2010, the DF-21D employs inertial guidance augmented by active radar or infrared seekers in the terminal phase for terminal homing.[52][53][54] The DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile extends anti-ship capabilities to greater distances, with a range of up to 4,000 kilometers, allowing strikes on assets as far as Guam. Dual-capable by design, the DF-26 supports rapid warhead interchange between conventional high-explosive and nuclear payloads without dismounting from its transporter-erector-launcher, enhancing operational flexibility for both land-attack and maritime missions. The anti-ship variant, designated DF-26B, incorporates a maneuverable reentry vehicle similar to the DF-21D, enabling precision targeting of time-sensitive maritime targets through integrated battle networks. Fielded since the mid-2010s, the DF-26 force has expanded significantly, with estimates indicating dozens of launchers operational by 2025.[3][55][56] In August 2025, China revealed the DF-26D variant during preparations for a military parade, featuring enhanced guidance for improved accuracy against dynamic naval targets and fortified bases, further blurring lines between conventional and nuclear roles in regional deterrence. This development underscores ongoing refinements in warhead survivability and sensor fusion, tested in simulations and live-fire exercises targeting mock carrier groups in the South China Sea. U.S. Department of Defense assessments highlight the DF-26's role in complicating freedom-of-navigation operations, though its effectiveness against defended carrier strike groups remains subject to debates over terminal-phase interception by systems like the SM-3.[57][58][47]Strategic and Operational Role

Nuclear Deterrence and Second-Strike Capability

The Dongfeng series of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), particularly the DF-31, DF-41, and silo-based DF-5 variants, constitute the primary land-based component of China's nuclear deterrent, designed to ensure a survivable second-strike capability under its no-first-use policy.[41] These systems enable assured retaliation by complicating enemy targeting through mobility, hardening, and payload diversity, thereby deterring nuclear aggression via the credible threat of overwhelming counterforce response.[59] China's strategic posture prioritizes minimal but robust deterrence, with an estimated 600 warheads deliverable by land-based ballistic missiles as of 2025, reflecting expansions driven by concerns over arsenal survivability amid advancing adversary countermeasures.[41] Road-mobile ICBMs like the solid-fueled DF-41, operational since around 2017 with a range exceeding 12,000 kilometers and capacity for 10-12 MIRVs, exemplify enhancements in second-strike reliability by evading satellite detection and pre-launch destruction through rapid deployment and terrain concealment.[60] The DF-41's variants, including rail-mobile options, further bolster this by distributing forces across vast territories, reducing vulnerability to first strikes compared to fixed silos.[60] Similarly, the DF-31 family, deployed since the early 2000s, provides intermediate survivability with ranges up to 11,000 kilometers, serving as a transitional force multiplier in China's nuclear modernization to counter potential U.S. or Russian preemptive capabilities.[61] Silo-based systems such as the liquid-fueled DF-5C, publicly displayed in September 2025 with global reach and multimegaton yields, complement mobile assets by offering hardened, dispersed launch points that demand disproportionate attacker resources for neutralization.[62] This diversification—evident in China's ongoing silo field expansions since 2021—addresses historical vulnerabilities in legacy forces, ensuring that even partial survival guarantees retaliatory strikes capable of inflicting unacceptable damage.[63] Recent parades, including the September 2025 event unveiling the full nuclear triad, underscored the Dongfeng ICBMs' integration into a layered deterrent, signaling prioritization of strategic stability through visible second-strike proficiency.[47]Conventional Precision Strike and A2/AD Doctrine

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) employs conventional variants of Dongfeng short-range and medium-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs and MRBMs) for precision strikes against fixed and mobile targets, enabling rapid, high-volume attacks with circular error probable (CEP) accuracies of 5–50 meters.[64] [65] Systems such as the DF-15 (600–900 km range) and DF-16 (800–1,000 km range) are road-mobile SRBMs optimized for submunitions warheads that crater runways and taxiways at air bases, with inventories estimated at approximately 300 launchers and 900 missiles across SRBM variants.[64] [65] MRBMs like the DF-21 series (1,000–3,000 km range), including the DF-21C land-attack variant and DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM), support strikes on infrastructure and naval assets, backed by 300 launchers and 1,300 missiles.[64] These capabilities are enhanced by advanced inertial navigation, satellite guidance, and maneuverable reentry vehicles, allowing terminal-phase adjustments for improved hit probability against defended targets.[66] In China's anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) doctrine, conventional Dongfeng missiles form the core of counter-intervention operations, particularly to deter or disrupt U.S. and allied forces in a Taiwan contingency by targeting forward air bases in Japan and Guam.[64] [65] Salvo fires—potentially hundreds of missiles—can close fighter runways for 40–280 hours and tanker operations for longer durations, denying sortie generation and air superiority within the First Island Chain.[65] The DF-21D and extended-range DF-26 ASBM variants extend this denial to carrier strike groups beyond 1,500 km, using over-the-horizon radars and satellite reconnaissance for terminal homing, thereby complicating U.S. naval power projection in the Western Pacific.[66] This approach prioritizes saturation of defenses through sheer volume and mobility, with road-transportable launchers dispersed across eastern and southern theater commands to enhance survivability.[64] Integration with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems, including AI-enhanced targeting, has improved operational tempo, as demonstrated in 2022 Taiwan Strait exercises where DF-series missiles simulated blockade and strike missions.[64] U.S. assessments indicate these forces could execute a "fait accompli" strategy, seizing objectives rapidly before external reinforcement, though vulnerabilities like command corruption and silo-based dependencies persist.[64] [65]| Missile Variant | Range (km) | Estimated CEP (m) | Primary Role in A2/AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| DF-15/DF-16 (SRBM) | 600–1,000 | 5–50 | Airfield cratering, Taiwan strikes[64] [65] |

| DF-21C/D (MRBM) | 1,000–3,000 | 10–50 | Land/ship targets, carrier denial[64] [66] |