Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

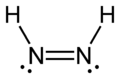

Diimide

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Diazene

| |||

| Other names

Diimide

Diimine Dihydridodinitrogen Azodihydrogen | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Diazene | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H2N2 | |||

| Molar mass | 30.030 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Yellow gas | ||

| Melting point | −80 °C (−112 °F; 193 K) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other anions

|

diphosphene dinitrogen difluoride | ||

Other cations

|

azo compounds | ||

Related Binary azanes

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Diimide, also called diazene or diimine, is a compound having the formula HN=NH. It exists as two geometric isomers, E (trans) and Z (cis). The term diazene is more common for organic derivatives of diimide. Thus, azobenzene is an example of an organic diazene.

Synthesis

[edit]A traditional route to diimide involves oxidation of hydrazine with hydrogen peroxide or air.[1]

- N2H4 + H2O2 → N2H2 + 2H2O

Alternatively the hydrolysis of diethyl azodicarboxylate or azodicarbonamide affords diimide:[2]

- Et−O2C−N=N−CO2−Et → HN=NH + 2 CO2 + 2 HOEt

Nowadays, diimide is generated by thermal decomposition of 2,4,6‐triisopropylbenzenesulfonylhydrazide.[3]

Because of its instability, diimide is generated and used in-situ. A mixture of both the cis (Z-) and trans (E-) isomers is produced. Both isomers are unstable, and they undergo a slow interconversion. The trans isomer is more stable, but the cis isomer is the one that reacts with unsaturated substrates, therefore the equilibrium between them shifts towards the cis isomer due to Le Chatelier's principle. Some procedures call for the addition of carboxylic acids, which catalyse the cis–trans isomerization.[4] Diimide decomposes readily. Even at low temperatures, the more stable trans isomer rapidly undergoes various disproportionation reactions, primarily forming hydrazine and nitrogen gas:[5]

- 2 HN=NH → H2N−NH2 + N2

Because of this competing decomposition reaction, reductions with diimide typically require a large excess of the precursor reagent.

Applications to organic synthesis

[edit]Diimide is occasionally useful as a reagent in organic synthesis.[4] It hydrogenates alkenes and alkynes with selective delivery of hydrogen from one face of the substrate resulting in the same stereoselectivity as metal-catalysed syn addition of H2. The only coproduct released is nitrogen gas. Although the method is cumbersome, the use of diimide avoids the need for high pressures or hydrogen gas and metal catalysts, which can be expensive.[6] The hydrogenation mechanism involves a six-membered C2H2N2 transition state:

Selectivity

[edit]Diimide is advantageous because it selectively reduces alkenes and alkynes and is unreactive toward many functional groups that would interfere with normal catalytic hydrogenation. Thus, peroxides, alkyl halides, and thiols are tolerated by diimide, but these same groups would typically be degraded by metal catalysts. The reagent preferentially reduces alkynes and unhindered or strained alkenes[1] to the corresponding alkenes and alkanes.[4]

Related

[edit]The dicationic form, H−N+≡N+−H (diazynediium, diprotonated dinitrogen), is calculated to have the strongest known chemical bond. This ion can be thought of as a doubly protonated nitrogen molecule. The relative bond strength order (RBSO) is 3.38.[7] F−N+≡N+−H (fluorodiazynediium ion) and F−N+≡N+−F (difluorodiazynediium ion) have slightly lower strength bonds.[7]

In the presence of strong bases, diimide deprotonates to form the pernitride anion, N−=N−.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ohno, M.; Okamoto, M. (1973). "cis-Cyclododecene". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 281.

- ^ Wiberg, E.; Holleman, A. F. (2001). "1.2.7: Diimine, N2H2". Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 628. ISBN 9780123526519.

- ^ Chamberlin, A. Richard; Sheppeck, James E.; Somoza, Alvaro (2008). "2,4,6-Triisopropylbenzenesulfonylhydrazide". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rt259.pub2. ISBN 978-0471936237.

- ^ a b c Pasto, D. J. (2001). "Diimide". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rd235. ISBN 0471936235.

- ^ Wiberg, Nils; Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Egon, eds. (2001). "1.2.7 Diimine N2H2 [1.13.17]". Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 628–632. ISBN 978-0123526519.

- ^ Miller, C. E. (1965). "Hydrogenation with Diimide". Journal of Chemical Education. 42 (5): 254–259. Bibcode:1965JChEd..42..254M. doi:10.1021/ed042p254.

- ^ a b Kalescky, Robert; Kraka, Elfi; Cremer, Dieter (12 September 2013). "Identification of the Strongest Bonds in Chemistry". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 117 (36): 8981–8995. Bibcode:2013JPCA..117.8981K. doi:10.1021/jp406200w. PMID 23927609. S2CID 11884042.