Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Doboj

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

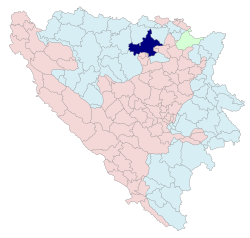

Doboj (Serbian Cyrillic: Добој, pronounced [dôboj])[1] is a city in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated on the banks of the Bosna river, in the northern region of Republika Srpska. As of 2013, it has a population of 71,441 inhabitants.

Doboj is the largest national railway junction and the operational base of the Railways Corporation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2] It is one of the oldest cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and, aside from Banja Luka, the most important urban center in northern Republika Srpska.

Geography

[edit]Prior to the Bosnian War, the municipality of Doboj had a larger surface area. Most of the pre-war municipality's territory is part of Republika Srpska, including the city itself. The southern rural areas are part of the Zenica-Doboj Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the eastern rural part of the municipality is part of the Tuzla Canton, also in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The parts of the pre-war Doboj Municipality that are in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina are the municipalities of Doboj South (Doboj Jug), Doboj East (Doboj Istok) and the Municipality of Usora. The northern suburbs of Doboj extend into the Pannonian plains, and effectively mark the southern tip of this great Central European plain. The southern (Doboj South) and eastern suburbs (Doboj East) are spread on the gentle hills which extend to the larger Central Bosnian mountain areas (Mt. Ozren in the southeast, Mt. Krnjin in the west).

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Doboj (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.4 (106.5) |

40.9 (105.6) |

39.8 (103.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

41.4 (106.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.7 (56.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.1 (84.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.8 (−10.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.2 (2.57) |

63.4 (2.50) |

68.3 (2.69) |

78.9 (3.11) |

109.1 (4.30) |

107.6 (4.24) |

94.2 (3.71) |

73.5 (2.89) |

85.9 (3.38) |

79.4 (3.13) |

79.1 (3.11) |

77.6 (3.06) |

982.2 (38.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 115.9 |

| Source: NOAA[3] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]Doboj has been continuously inhabited ever since the Neolithic times. Fragments of pottery and decorative art were found on several localities, with the most known site in Makljenovac, south from the city proper, at the confluence of the Usora and Bosna rivers. Archeological findings from the Paleolithic era were found in a cave in the Vila suburb.[4]

The Illyrian tribe of Daesitates settled in this region as early as the twelfth century BC. Daesitates were one of the largest and most important Illyrian tribes residing at the territory of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, sharing their northern borders with Breuci, another important tribe. Daesitates and Breuci started the Great Illyrian Revolt, or in Roman sources, the widespread rebellion known as Bellum Batonianum (6–9 AD). After the bloody rebellion was subdued, Roman legions permanently settled in the area and built a large military camp (Castrum) and a civilian settlement (Canabea) in Makljenovac. These structures were most likely built in the early Flavian dynasty era, during Vespasian's rule.

The military camp was large, in the shape of a near perfect rectangle with large towers at each corner and the main gate in the middle of the central wall, and served as the most important defense on the old Roman road from Brod to Sarajevo, demarcating the very borders of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia. It served its role for several centuries with the evidence of Belgian and Spanish cohorts stationed there in the second and third century AD. Canabea contained Roman settlers, with evidence of a large bathhouse with a hypocaust (central heating) and a concubine house for soldiers stationed at the nearby Castrum. A large Villa Rustica was located in the modern-day suburb of Doboj, appropriately named Vila. Very fine pieces of religious and practical artefacts were found at these sites, including an altar dedicated to Jupiter, figurines of Mars, and fragments of African made Terra sigillata pottery. When South Slavic tribes migrated into this area in the sixth and seventh century AD, they had settled initially on the ruins of the previous Roman settlement and lived there continuously until the early thirteenth century at which point they used stones and building material from the old Roman Castrum in order to build the stone foundation of the Gradina fortress, several kilometers north, in the modern-day old town of Doboj. Nowadays only the walls of the former camp and civilian settlement are still open to visitors.

Middle Ages

[edit]

The first official mention of the city itself is from 1415, in a charter issued by Dubrovnik to the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, although there are numerous artefacts and objects that have been found (kept in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo and the Regional Museum in Doboj), which confirm that the area had been inhabited ever since the early Stone Age, and that the Roman Empire had an army camp (Castrum) and a settlement (Canabea) in the vicinity of the town dating from the first century AD.[5][6] Following the arrival of the Slavs in the sixth century it became a part of the region/Usora banate (in medieval documents sometimes collectively mentioned with the nearby province of Soli, hence, Usora and Soli).

The Doboj fortress, a royal Kotromanić fortress, was first built in the early thirteenth century and then expanded in the early fifteenth century (1415). It was expanded again during Ottoman rule in 1490. This newer stone foundation of the fortress was built on previous layers of an older foundation (dating back to the ninth or tenth century) made of wood, mud and clay (Motte-and-bailey type).[7] It was a very important obstacle for invaders coming from the north, Hungarians, and later on, Austrians and Germans. It was built in the Gotho-Roman style with Gothic towers and Romanesque windows. The area saw numerous battles in medieval times and the fortress often changed hands between Bosnian and Hungarian armies.[7] Doboj was the site of a particularly major battle between the Hungarians and a Bosnian-Turkish coalition in early August 1415 in which the Hungarians were heavily defeated on the field where the modern city of Doboj lies today.[8] As an important border fortress between the Bosnian Kingdom and Hungary it was also frequently attacked, officially recorded as 18 times, in the Austro-Ottoman Wars, and fell to the Austro-Hungarians in 1878.

World War I and World War II

[edit]During World War I, Doboj was the site of the largest Austro-Hungarian concentration camp.[9] According to the official figures, it held in total 45,791 people between 27 December 1915 and 5 July 1917, of which:[10][11]

- 16,673 men from Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 16,996 women and children from Bosnia and Herzegovina (mostly of Serb ethnicity)

- 9,172 soldiers and civilians (men, women, children) from the Kingdom of Serbia

- 2,950 soldiers and civilians from the Kingdom of Montenegro

Some 12,000 people had died in this camp, largely due to malnutrition and poor sanitary conditions.

By February 1916, the authorities began redirecting the prisoners to other camps. Bosnian Serbs were mostly sent to Győr (Sopronyek, Šopronjek/Шопроњек).[12]

Most of the prisoners from Bosnia were entire families from the border regions of eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is said that 5,000 families alone were uprooted from the Sarajevo district in eastern Bosnia along the border with the Kingdoms of Serbia & Montenegro.[10]

From 1929 to 1941, Doboj was part of the Vrbas Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

After the creation of the Independent State of Croatia in April 1941, the Jesuit priest Dragutin Kamber was appointed as the grand prefect of Doboj.[13] He oversaw the mass arrest and internment of Serbs, many of whom were interrogated in his house before being executed in its basement. Kamber also supervised the rollout of Ustaše race laws in the district, ordering that Jews were to wear yellow armbands and Serbs were to wear white ones.[14] The historian Robert B. McCormick estimates that Kamber "sent hundreds of Serbs to their deaths."[15] During this time, the Ustaše deported Serbs, Jews and Roma, as well as pro-Partisan civilians, to concentration and labor camps. According to public records, 291 civilians from Doboj of all ethnicities perished in the Jasenovac concentration camp.[16] In 2010, the remains of 23 people killed by the Partisans were found in two pits near the Doboj settlement of Majevac.[17] The non-governmental organization which discovered the remains alleges that nearby pits contain the remains of hundreds more also killed by the Partisans.

Doboj was an important site for the Partisan resistance. From their initial uprising in August 1941 up until the end of the war, the Ozren Partisan squadron carried out numerous actions against the occupation forces, among the first successful operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city was an important stronghold for permanently stationed Ustaše Militia and Croatian Home Guard garrisons with smaller Wehrmacht units serving as liaison and in defense of important roads and railroads. The Waffen SS "Handschar" division was partly mobilized from the local Muslim population and participated in battles around Doboj in the summer and fall of 1944.

Doboj with its surrounding area, the Ozren and Trebava mountains, was also a particularly important site for local Chetniks. They participated in battles against the Ustaše, Home Guards, and the Wehrmacht, initially allied with local Partisan units and then alone, after breaking ties with the Partisans in April 1942. In November 1944, the elements of the Ozren Chetnik Corps and the Trebava Chetnik Corps partook in the Operation Halyard, the largest US rescue mission behind enemy lines. They built an airstrip in the village of Boljanić from which rescued US Airmen flew to safety to Bari, Italy.

The town was eventually liberated by the Yugoslav Partisans on 17 April 1945. The units involved were the 14th Central Bosnian Brigade and the 53rd Division.

SFR Yugoslavia

[edit]The city was flooded in May 1965.[18] During this period, the city experienced mass industrialization, becoming one of the most important industrial hubs in Yugoslavia.

Bosnian War

[edit]Doboj was strategically important during the Bosnian War. In May 1992, the control of Doboj was held by Bosnian Serb forces and the Serb Democratic Party governed the city. What followed was mass disarming and subsequently mass arrests of all non-Serb civilians (mainly Bosniaks and Croats).

Doboj was heavily shelled throughout the entire war by local Bosniak and Croatian forces. More than 5,500 shells, mortar rounds, and other projectiles were fired into the city proper and some 100 civilians were killed and more than 400 were wounded and maimed during the indiscriminate shelling.

A number of instances of war crimes and ethnic cleansing were committed by Bosnian Serb forces. Biljana Plavšić, Radovan Karadžić, Momčilo Krajišnik and others planned, instigated, ordered, committed or otherwise aided and abetted the planning, preparation or execution of the destruction of the Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats.[19][20] Plavšić was charged with crimes against humanity that include but are not limited to the killings in Doboj. Her indictment was related to genocide charges in Doboj specifically.

Bosnian Serb forces were implicated in the systematic looting and destruction of Bosniak and Croat properties during the Bosnian War. A number of women were raped and civilians tortured or killed. All the mosques in the town were destroyed. A number of mass executions took place in Spreča Prison, on the banks of the river Bosna and in the "July 4th" military barrack in the village of Miljkovac, all in 1992. Many of the non-Serbs were detained at various locations in the town, subjected to inhumane conditions, including regular beatings, torture and forced labour. A school in Grapska and the factory used by the Bosanka company that produced jams and juices in Doboj was used as a rape camp. Four different armies of soldiers were present at the rape camps, including the local Serbian militia, the Yugoslav army (JNA), police forces based in the Serbian-occupied town of Knin and members of the White Eagles paramilitary group. The man who oversaw the women's detention in the school was Nikola Jorgić, a former police officer in Doboj, who had been convicted of genocide in Germany but died during the serving of his life sentence.[21][22]

After the Dayton Agreement and the peace following in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the city served as a major HQ/base for IFOR (later SFOR) units.

The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina is processing several cases for other war crimes in Doboj.[23]

2014 floods

[edit]In May 2014, Doboj was the city in Bosnia and Herzegovina that accounted for the most damage and casualties during and following the historic rainfall that caused massive flooding and landslides, taking the lives of at least 20 people in Doboj alone.

Throughout the two weeks after the beginning of the natural disaster, the corpses of victims were still being found on the streets, in homes and automobiles.[24] On 26 May 2014, it was announced that the floods and landslides had uncovered mass graves with the skeletal remains of Bosniak victims of the Bosnian War of the 1990s.[25] The mass graves are located in the Usora Municipality and the exact number of victims is as of yet unknown.

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Population of settlements – Doboj municipality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlement | 1948. | 1953. | 1961. | 1971. | 1981. | 1991. | 2013. | |

| Total | 33,504 | 56,442 | 74,956 | 88,985 | 99,548 | 95,213 | 71,441 | |

| 1 | Boljanić | 2,327 | 1,714 | |||||

| 2 | Božinci Donji | 587 | 329 | |||||

| 3 | Brestovo | 1,254 | 644 | |||||

| 4 | Bukovica Mala | 816 | 752 | |||||

| 5 | Bukovica Velika | 1,481 | 2,669 | |||||

| 6 | Bušletić | 787 | 556 | |||||

| 7 | Čajre | 456 | 289 | |||||

| 8 | Cerovica | 1,701 | 1,030 | |||||

| 9 | Čivčije Bukovičke | 1,017 | 658 | |||||

| 10 | Čivčije Osječanske | 538 | 294 | |||||

| 11 | Cvrtkovci | 897 | 581 | |||||

| 12 | Doboj | 13,415 | 18,264 | 23,558 | 27,498 | 26,987 | ||

| 13 | Donja Paklenica | 764 | 483 | |||||

| 14 | Dragalovci | 1,031 | 367 | |||||

| 15 | Glogovica | 714 | 517 | |||||

| 16 | Gornja Paklenica | 628 | 398 | |||||

| 17 | Grabovica | 798 | 598 | |||||

| 18 | Grapska Donja | 494 | 445 | |||||

| 19 | Grapska Gornja | 2,297 | 1,334 | |||||

| 20 | Jelanjska | 701 | 435 | |||||

| 21 | Kladari | 673 | 520 | |||||

| 22 | Kostajnica | 1,342 | 1,596 | |||||

| 23 | Kotorsko | 3,295 | 1,790 | |||||

| 24 | Kožuhe | 1,471 | 999 | |||||

| 25 | Lipac | 1,018 | 1,246 | |||||

| 26 | Ljeb | 446 | 325 | |||||

| 27 | Ljeskove Vode | 821 | 613 | |||||

| 28 | Majevac | 456 | 329 | |||||

| 29 | Makljenovac | 2,164 | 1,165 | |||||

| 30 | Miljkovac | 1,430 | 838 | |||||

| 31 | Mitrovići | 441 | 233 | |||||

| 32 | Opsine | 351 | 230 | |||||

| 33 | Osječani Donji | 821 | 687 | |||||

| 34 | Osječani Gornji | 1,259 | 1,084 | |||||

| 35 | Osojnica | 676 | 369 | |||||

| 36 | Osredak | 605 | 282 | |||||

| 37 | Ostružnja Donja | 1,130 | 838 | |||||

| 38 | Ostružnja Gornja | 495 | 380 | |||||

| 39 | Paležnica Gornja | 342 | 328 | |||||

| 40 | Pločnik | 304 | 261 | |||||

| 41 | Podnovlje | 1,239 | 1,156 | |||||

| 42 | Potočani | 897 | 605 | |||||

| 43 | Pridjel Donji | 987 | 841 | |||||

| 44 | Pridjel Gornji | 1,247 | 777 | |||||

| 45 | Prnjavor Mali | 793 | 568 | |||||

| 46 | Radnja Donja | 572 | 368 | |||||

| 47 | Raškovci | 666 | 460 | |||||

| 48 | Ritešić | 584 | 327 | |||||

| 49 | Rječica Donja | 302 | 215 | |||||

| 50 | Rječica Gornja | 483 | 314 | |||||

| 51 | Ševarlije | 1,792 | 1,271 | |||||

| 52 | Sjenina | 1,950 | 1,028 | |||||

| 53 | Sjenina Rijeka | 679 | 402 | |||||

| 54 | Stanari | 1,299 | 1,015 | |||||

| 55 | Stanić Rijeka | 1,002 | ||||||

| 56 | Stanovi | 1,073 | 760 | |||||

| 57 | Striježevica | 597 | 433 | |||||

| 58 | Suho Polje | 924 | 576 | |||||

| 59 | Svjetliča | 906 | 614 | |||||

| 60 | Tekućica | 736 | 630 | |||||

| 61 | Trnjani | 887 | 609 | |||||

| 62 | Zarječa | 350 | 293 | |||||

| 63 | Zelinja Gornja | 274 | ||||||

Ethnic composition

[edit]| Ethnic composition – Doboj city | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013.[26] | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||

| Total | 26,987 (100,0%) | 27,498 (100,0%) | 23 558 (100,0%) | 18,264 (100,0%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 3,797 (15,1%) | 11,154 (40,56%) | 8,822 (37,45%) | 8,976 (49,15%) | |||

| Serbs | 19,586 (77,9%) | 8,011 (29,13%) | 6,091 (25,86%) | 5,044 (27,62%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 4,365 (15,87%) | 5,211 (22,12%) | 919 (5,032%) | ||||

| Croats | 704 (2,8%) | 2,714 (9,870%) | 2,852 (12,11%) | 2,889 (15,82%) | |||

| Others | 1,045 (4,2%) | 1 254 (4,560%) | 234 (0,993%) | 169 (0,925%) | |||

| Montenegrins | 171 (0,726%) | 175 (0,958%) | |||||

| Roma | 76 (0,323%) | 1 (0,005%) | |||||

| Albanian | 54 (0,229%) | 35 (0,192%) | |||||

| Macedonians | 20 (0,085%) | 15 (0,082%) | |||||

| Slovenes | 16 (0,068%) | 25 (0,137%) | |||||

| Hungarians | 11 (0,047%) | 16 (0,088%) | |||||

| Ethnic composition – Doboj municipality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||

| Total | 71,441 (100,0%) | 95,213 (100,0%) | 99,548 (100,0%) | 88,985 (100,0%) | |||

| Serbs | 52,628 (73,67%) | 39,820 (38,83%) | 39,224 (39,40%) | 39,884 (44,82%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 15,322 (21,45%) | 41,164 (40,14%) | 35,742 (35,90%) | 32,418 (36,43%) | |||

| Croats | 1,845 (2,583%) | 13,264 (12,93%) | 14,522 (14,59%) | 14,754 (16,58%) | |||

| Others | 1,646 (2,304%) | 2,536 (2,473%) | 1,043 (1,048%) | 453 (0,509%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 5,765 (5,622%) | 8,549 (8,588%) | 1,124 (1,263%) | ||||

| Montenegrins | 225 (0,226%) | 214 (0,240%) | |||||

| Albanians | 95 (0,095%) | 60 (0,067%) | |||||

| Roma | 76 (0,076%) | 1 (0,001%) | |||||

| Macedonians | 32 (0,032%) | 28 (0,031%) | |||||

| Slovenes | 26 (0,026%) | 30 (0,034%) | |||||

| Hungarians | 14 (0,014%) | 19 (0,021%) | |||||

Urban area by settlements (1991)

[edit]- Bare: 732 (62%) Serbs; 153 (13%) Yugoslavs; 135 (11%) Croats; 112 (9%) Bosniaks; 53 (4%) others, 1,185 total

- Centar: 3,720 (35%) Serbs; 3,365 (31%) Bosniaks; 1,982 (18%) Yugoslavs; 1,236 (12%) Croats; 432 (4%) others, 10,735 total

- Čaršija: 3,561 (72%) Bosniaks; 594 (12%) Yugoslavs; 303 (6%) Serbs; 195 (4%) Croats; 273 (6%) others, 4,926 total

- Doboj Novi: 358 (48%) Bosniaks; 237 (32%) Serbs; 39 (5%) Yugoslavs; 7 (1%) Croats; 108 (14%) others, 749 total

- Donji Grad: 1,879 (37%) Serbs; 1,547 (31%) Bosniaks; 844 (17%) Yugoslavs; 569 (11%) Croats; 196 (4%) others, 5,035 total

- Orašje: 1,411 (66%) Bosniaks; 293 (14%) Serbs; 231 (11%) Yugoslavs; 111 (5%) Croats, 90 (4%) others, 2,136 total

- Usora: 924 (33%) Serbs; 779 (28%) Bosniaks; 502 (18%) Croats; 491 (17%) Yugoslavs; 117 (4%) others, 2,813 total

Economy

[edit]As a railway hub, before the Bosnian War, Doboj focused much of its industrial activities around it. Moreover, as a regional center, it was home to several factories, now mostly bankrupt from mismanagement or privatization, including "Bosanka Doboj", a fruit and vegetable produce factory; "Trudbenik", a maker of air compressors and equipment, etc. Nowadays, most of the economy, similar to the rest of the country and typical for the poorly executed transition from state-controlled to a market economy, is based around the service industry. High unemployment warrants a vibrant coffee shop and bar scene, crowded throughout most of the day and night (it is commonly believed that Doboj is one of the top three cities having the largest number of cafes and bars/pubs within city limits in Bosnia & Herzegovina).

In 1981, Doboj's GDP per capita was 53% of the Yugoslav average.[28]

- Economic preview

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in professional fields per their core activity (as of 2018):[29]

| Professional field | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 166 |

| Mining and quarrying | 108 |

| Manufacturing | 1,061 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 340 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 223 |

| Construction | 733 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 2,446 |

| Transportation and storage | 1,600 |

| Accommodation and food services | 605 |

| Information and communication | 230 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 248 |

| Real estate activities | 1 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 261 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 321 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 1,226 |

| Education | 1,208 |

| Human health and social work activities | 1,315 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 50 |

| Other service activities | 338 |

| Total | 12,480 |

Transportation

[edit]The city is the region's primary railroad junction, going south to Ploče on the Adriatic Sea, west to Banja Luka and Zagreb, north to Vinkovci, Croatia, and east to Tuzla, Bijeljina and Zvornik. A highway toward western RS and Banja Luka has been completed and opened since 2018.

Society

[edit]Education

[edit]Doboj hosts the private Slobomir P University, with several colleges like the Faculty of information technology; the Faculty of economics and management; the Faculty of philology; the Faculty of law; a Fiscal Academy and the Academy of Arts. Doboj also seats the Mechanical and Electrical Engineering Technical School, as well as several specialized high schools.

Doboj also hosts the public Faculty of Transport and Traffic Engineering, a branch of the University of East Sarajevo with several departments: Road & Urban Transport; Rail Transport; Postal Transport; Telecommunication and Logistics. Since the 2015/2016 academic year, it has opened new departments: Air Transport; Roads; IT Transport and Motor Vehicles.

Sport

[edit]

The local football club, Sloga Doboj, plays in the First League of the Republika Srpska. The town's favourite sport, however, is handball. The local handball club is Sloga Doboj. Sloga Doboj ranks among the country's top teams and consistently qualifies for international competitions. Very importantly, Doboj traditionally hosts "The Annual Doboj International Champions' Handball Tournament" every year during the last days of August. Its 55th tournament was in 2023 and once again. The prestige of this EHF-listed tournament was consistently strong enough to attract the most important names in the European team handball over the past five decades such as: Barcelona, Grasshopper, Gummersbach, Ademar León, CSKA, Steaua, Dinamo București, Atlético Madrid, Red Star, Metaloplastika, Partizan, Pelister, Nordhorn, Pick Szeged, Veszprém, Göppingen, Montpellier, d'Ivry and Chekhovski Medvedi.

Symbol

[edit]The four squares represent the four mountains which mark the outer borders of the Doboj valley in which the City of Doboj lies in: Ozren, Trebava, Vučjak, and Krnjin. The fleur-de-lis represent the medieval origins of the city in the royal fortress Gradina built by the kings from the medieval Bosnian dynasty of Kotromanić.

Notable places

[edit]- The Doboj Fortress from the early thirteenth century, looking over the town.

- A Roman military camp (Castrum) from the first century AD (right above the confluence of the Usora and the Bosna rivers)

- Goransko Jezero, lake and recreation park in the vicinity of town.

Notable people

[edit]- Aleksandar Đurić, Singapore footballer

- Bojan Šarčević, basketball player

- Borislav Paravac, politician

- Danijel Pranjić, Croatian footballer

- Danijel Šarić, Bosnian-Qatari handball player

- Dina Bajraktarević, singer

- Dino Djulbic, Australian footballer

- Dragan Mikerević, politician

- Fahrudin Omerović, footballer

- Igor Vukojević, singer

- Indira Radić, singer

- Izet Sarajlić, historian

- Jasmin Džeko, footballer

- Krešimir Zubak, politician

- Mirsada Bajraktarević, singer

- Nenad Marković, basketball player

- Ognjen Kuzmić, Serbian basketball player

- Pero Bukejlović, politician

- Sejad Halilović, former footballer

- Silvana Armenulić, singer

- Spomenko Gostić, soldier

- Vladimir Tica, Serbian basketball player

- Vlastimir Jovanović, footballer

- Zoran Kvržić, footballer

- Aidin Mahmutović, footballer

- Zdenko Križić, Croatian Roman Catholic prelate

- Benjamin Burić, handball goalkeeper

- Senjamin Burić, handballer

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mangold, Max (2005). Das Aussprachewörterbuch (in German) (6th ed.). Mannheim: Dudenverlag. p. 279. ISBN 9783411040667.

- ^ "Bosnia and Herzegovina Railways Public Corporation contact". www.bhzjk.ba. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Doboj Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Visit Doboj. The Oldest Town in Bosnia". sarajevskasehara. January 2020.

- ^ "About Doboj". novihorizonti.sf.ues.rs.ba.

- ^ "Visiting Doboj". visitbih.ba. 1 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Doboj, the oldest town in Bosnia". sarajevskasehara.com. 27 January 2020.

- ^ Čuvalo, Ante (2010). The A to Z of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Scarecrow Press. p. 253. ISBN 9781461671787.

- ^ Paravac, Dušan (2002). Dobojski logor: hronika o austrougarskom logoru interniraca u Doboju : 1915-1917. Narodna Biblioteka. ISBN 9788675360087.

- ^ a b Paravac, Dušan (1970). Logor Smrti. Glas Komuna. pp. 5–50.

- ^ "Обиљежено страдање Срба у аустроугарском логору у Добоју". spc.rs (in Serbian). Serbian Orthodox Church. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016.

- ^ Lukić, Nenad (2016). "Popis umrlih Srba u logoru Šopronjek/Nekenmarkt 1915–1918. godine" [List of deceased Serbs in the camp Sopronyek/Neckenmarkt 1915–1918].

- ^ Redžić, Enver (2005) [1998]. Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Translated by Aida Vidan. Abingdon-on-Thames, England: Frank Cass. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- ^ Aarons, Mark; Loftus, John (1998) [1991]. Unholy Trinity: The Vatican, The Nazis, and The Swiss Banks. New York City: St. Martin's Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-3121-8199-4.

- ^ McCormick, Robert B. (2014). Croatia Under Ante Pavelić: America, the Ustaše and Croatian Genocide. New York City: I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78076-712-3.

- ^ "Jasenovac". cp13.heritagewebdesign.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Kod Doboja otkopali kosture žrtava iz 1945". Mondo.rs. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Doboj potopljen istog dana kao i pre 46 godina". Telegraf. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Prosecutor v. Biljana Plavsic judgement" (PDF). Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Prosecutor v. Momcilo Krajisnik judgement" (PDF).

Sentenced to 27 years' imprisonment

- ^ "HUDOC Search Page". Cmiskp.echr.coe.int. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Helsinki Watch (1993). War crimes in Bosnia-Hercegovina. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-097-9.

- ^ "Institute for War and Peace Reporting". Iwpr.net. 30 April 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Pronađeno tijelo muškarca, broj žrtava u RS dosegao 19". Radio Sarajevo. 24 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Poplave otkrile nove masovne grobnice". Radio Sarajevo. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Popis 2013 u BiH". www.statistika.ba. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Bosnian Congres – census 1991 – North of Bosnia". Hdmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Radovinović, Radovan; Bertić, Ivan, eds. (1984). Atlas svijeta: Novi pogled na Zemlju (in Croatian) (3rd ed.). Zagreb: Sveučilišna naklada Liber.

- ^ "Cities and Municipalities of Republika Srpska" (PDF). rzs.rs.ba. Republika Srspka Institute of Statistics. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Gradovi pobratimi". doboj.gov.ba (in Bosnian). Doboj. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

External links

[edit]Doboj

View on GrokipediaDoboj is a city and municipality in northern Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the valley of the Bosna River at the confluence of the Usora and Spreča rivers.[1][2] First documented in a charter issued by Dubrovnik on June 28, 1415, it ranks among the region's earliest recorded settlements, with archaeological evidence suggesting prehistoric human activity in the surrounding area.[3][4] The municipality spans 648 square kilometers and had an estimated urban population of 58,305 in 2022, reflecting a gradual decline due to post-war emigration and low birth rates.[5] As the largest railway junction in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Doboj hosts the operational headquarters of the national railways, facilitating trade and connectivity across the Balkans.[6] Its economy centers on manufacturing sectors such as metal processing, food production, and textiles, supported by proximity to raw materials and transport infrastructure, though challenged by structural inefficiencies inherited from socialist-era industry.[7] During the 1992–1995 Bosnian War, Doboj served as a strategic Bosnian Serb stronghold amid ethnic conflicts, involving population displacements and documented atrocities that reshaped its demographics, with non-Serb communities largely departing under duress.[8] The city's medieval fortress, overlooking the rivers, symbolizes its historical defensive role and remains a prominent landmark.[9]

Geography

Location and Physical Features

Doboj lies in the northern part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, within the Republika Srpska entity, positioned along the Bosna River in the Posavina region.[10] The city center is at the confluence of the Bosna, Usora, and Spreča rivers, a geostrategic location that has influenced settlement and fortification development due to the natural defensive advantages provided by the river valleys and adjacent elevations.[11] [6] The urban core occupies an alluvial plain formed by the Bosna River, extending to the lowest slopes of the surrounding Krnjin, Ozren, and Trebava mountain ranges, which rise to moderate heights and contribute to a landscape of river flats interspersed with foothills.[10] This terrain features typical northern Bosnian valley characteristics, with the city itself at an elevation of approximately 144 meters above sea level, facilitating agriculture and transport while bordered by hilly uplands.[12] The Bosna River, one of the country's major internal waterways measuring 271 kilometers in length, dominates the local hydrology, supporting floodplain ecosystems amid the transitional topography between plains and mountains.[13]Climate and Environmental Conditions

Doboj has a humid continental climate classified as Dfb under the Köppen system, featuring distinct seasons with warm to hot summers and cold, snowy winters.[14] Average annual temperatures hover around 11°C (52°F), with July highs reaching 28°C (82°F) and January lows dropping to -3°C (27°F); extremes occasionally fall below -10°C (14°F) or exceed 34°C (93°F).[14] Precipitation totals approximately 997 mm (39 inches) per year, distributed relatively evenly but peaking in May at about 105 mm (4.1 inches), supporting agriculture while contributing to periodic flooding risks along the Bosna and Usora rivers.[15] The region's environmental conditions are influenced by its position in the Posavina lowlands, with fertile alluvial soils and surrounding temperate deciduous forests dominated by oak and beech species. Air quality remains generally moderate, with particulate matter levels occasionally elevated due to seasonal wood burning and traffic, though rarely exceeding WHO guidelines outside winter inversions.[16] Natural hazards include recurrent flooding, as evidenced by severe inundations in May 2014 that submerged parts of the city, displacing thousands and highlighting vulnerabilities tied to heavy spring rains and inadequate drainage infrastructure.[17]History

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The region around Doboj was part of the Roman province of Dalmatia following the conquest of Illyrian territories in the 1st century BCE. Archaeological evidence from the castrum at Makljenovac, located near modern Doboj, indicates a Roman military presence, with the site occupied by the Cohors prima Delmatarum milliaria equitata. Excavations in 1959 and 1960, led by Irma Čremošnik, revealed fortifications and artifacts dating primarily to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, underscoring the strategic importance of the area for Roman control over local routes and resources.[18][19] Slavic tribes settled in the broader Bosnian region during the 6th and 7th centuries CE, integrating with remnant Romanized populations and establishing early principalities. By the 12th century, the area fell under the influence of the emerging Bosnian state. In the medieval period, Doboj developed as a key stronghold in the Usora domain of the Banate of Bosnia under the Kotromanić dynasty. The fortress, initially featuring wooden and clay structures possibly from the 10th–11th centuries, was rebuilt in stone during the early 13th century, serving as a royal defensive outpost controlling valleys and trade routes. It frequently alternated between Bosnian and Hungarian control amid regional conflicts.[20][9] A pivotal event was the Battle of Doboj in 1415, where Bosnian forces, supported by Ottoman auxiliaries, defeated an invading Hungarian army under King Sigismund, preserving local autonomy temporarily. The fortress underwent significant reconstruction that year, incorporating Gothic elements, and remained a focal point of resistance until the Ottoman conquest in the mid-15th century. Recent excavations in 2016–2017 uncovered medieval weaponry and ceramics, confirming its military role.[20][21]Ottoman Era and Early Modern Developments

Doboj came under Ottoman control in the 1470s, annexed to the Sanjak of Bosnia alongside other towns in the Bosnian basin.[9] The fortress of Gradina, originally medieval, was reconstructed by Ottoman authorities, who added outer walls and adapted it for defense against Hungarian incursions, enhancing its role as a border stronghold commanding the Usora province highway.[9] This fortification underscored Doboj's strategic military importance in the Ottoman frontier system. Urban development accelerated under Ottoman administration, with the construction of the Selimiye Mosque complex in the čaršija (old town center) likely before 1512–1520, during the reign of Selim I or II, as evidenced by its mention in records from 1604.[22] The mosque featured a single-space prayer hall with a hemispherical dome, a slender minaret, and a portico, serving as a hub for religious and social life; archaeological evidence reveals burials of upper-class Muslim families, such as a child interred in the harem, alongside artifacts like pottery, tobacco pipes, and animal bones indicating ritual practices during Eid al-Adha.[23] [24] Administrative structures evolved in the early modern period; following the Peace of Belgrade in 1739, a Doboj captaincy was established to govern the town and environs, manned by 171 commanders and soldiers.[9] The fortress and mosque underwent reconstructions after damages in 1703 and 1718, reflecting ongoing Ottoman investment amid Habsburg-Ottoman conflicts, though its primary military function declined by 1851.[22] Ottoman rule persisted until the Austro-Hungarian occupation in 1878, marking the transition from early modern imperial governance.[9]20th Century: World Wars and Yugoslav Period

During World War I, Doboj served as the site of an Austro-Hungarian concentration camp established for the internment of Serbs from Bosnia and other regions, with the first mass transport arriving on December 27, 1915.[25] The camp held over 45,000 Serbs, many interned without specific charges, resulting in more than 12,000 deaths from disease, starvation, and executions, including 643 children in April 1916 alone; it operated until its closure on July 5, 1917.[26] [27] Serbian historical accounts describe these conditions as part of a systematic genocide against Serbs, though Austro-Hungarian records attribute deaths primarily to typhus epidemics exacerbated by overcrowding.[28] In the interwar Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), Doboj functioned as a regional administrative and transportation hub within the Vrbas Oblast from 1922 and then the Vrbas Banovina after 1929, benefiting from its position at the confluence of rail lines connecting Zagreb, Sarajevo, and Belgrade.[6] Limited records indicate steady population growth and agricultural expansion, with no major recorded conflicts, though ethnic tensions simmered amid broader Yugoslav centralization efforts under King Alexander I. World War II saw Doboj occupied by Axis forces on April 15, 1941, following the invasion of Yugoslavia, and incorporated into the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), where Ustaše authorities imposed repressive measures, including deportations of the local Jewish population—estimated at around 200 individuals—to camps from which few returned.[4] [29] The area became a focal point for multi-factional resistance, with Yugoslav Partisans launching uprisings from August 1941 and engaging in battles against Ustaše, Chetnik, and German forces through the summer and fall, leveraging Doboj's rail infrastructure for sabotage operations.[30] [31] Liberation occurred on April 17, 1945, by advancing Red Army and Partisan units, marking the end of NDH control and facilitating Doboj's integration into the emerging socialist state.[32] Under the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), Doboj evolved into a key industrial and logistical node in the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with post-war reconstruction emphasizing rail and road expansions that positioned it as a vital crossroads for freight and passenger traffic across northern Bosnia.[4] State-led initiatives drove growth in manufacturing, including metalworking and food processing, transforming the city into a regional economic center by the 1970s, though underlying ethnic frictions persisted amid Yugoslavia's federal structure; population data from the 1981 census recorded approximately 40,000 residents, reflecting steady urbanization.[32] This period saw no major internal upheavals specific to Doboj until the federation's dissolution in 1991, with development aligned to Tito's non-aligned industrialization model.[4]Bosnian War: Events, Atrocities, and Perspectives

In early 1992, following Bosnia and Herzegovina's declaration of independence from Yugoslavia on March 3, tensions escalated in Doboj municipality, where multi-ethnic Territorial Defense (TO) units clashed amid fears of partition along ethnic lines. Bosnian Serb leaders, aligned with the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska, mobilized forces including elements of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and local Serb TO to secure strategic positions, viewing the independence referendum of February 29–March 1 as a threat to Serb-majority areas.[33] By late March, Bosnian Serb forces had begun asserting control over parts of the municipality, with intensified operations in April amid sporadic fighting between Serb, Bosniak, and Croat armed groups.[34] The decisive takeover occurred on May 3, 1992, when Bosnian Serb Army (VRS) units, supported by police and paramilitaries, captured Doboj town after brief but fierce combat with Bosniak and Croat TO fighters, resulting in the surrender or flight of non-Serb forces.[35] This event marked the establishment of full Serb administrative and military control, with the formation of a "Crisis Committee" to govern the area. Immediately following, non-Serb civilians faced restrictions on movement, property seizures, and forced labor, as documented in tribunal records of systematic persecution.[36] The town became a rear base for VRS operations, with its rail and road links used for logistics toward central Bosnia fronts. Detention facilities were rapidly established, including the KP Dom prison in Doboj from May 1992, where hundreds of Bosniak and Croat males were held without trial, subjected to beatings, interrogations, and executions.[33] Specific atrocities included the killing of detainees at sites like Mehmed Šahorić's facility on or about May 26, 1992, and sexual assaults on female prisoners, as alleged in indictments against local Serb officials.[34] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) later convicted figures such as police commander Stevan Todorović for persecution involving unlawful detentions and murders in Doboj camps, confirming patterns of torture and extrajudicial killings targeting non-Serbs. Human Rights Watch reported that such abuses in Doboj, beginning as early as March 1992, aimed to terrorize the Bosniak population into submission or flight.[37] Ethnic cleansing operations displaced over 20,000 non-Serbs from Doboj municipality by mid-1992, through forced expulsions, destruction of non-Serb homes and mosques, and orchestrated "exchanges" of populations.[35] Verified incidents included mass roundups and deportations via convoys to Bosniak-held areas like Zenica, often under threat of death, contributing to the near-homogenization of the region under Serb control.[38] Casualty figures remain disputed, but ICTY evidence points to at least dozens of confirmed civilian deaths from targeted killings, with broader war-related fatalities in the municipality exceeding 500 by war's end, predominantly non-Serbs.[39] Perspectives on these events diverge sharply along ethnic lines. Bosniak accounts, supported by survivor testimonies in ICTY proceedings, frame the takeover and subsequent abuses as premeditated aggression by Serb forces to eradicate non-Serb presence, akin to genocide in intent if not scale.[33] Serb narratives, articulated by local leaders and echoed in Republika Srpska historiography, portray the actions as defensive measures against perceived Bosniak-Croat encirclement and attacks on Serb villages, emphasizing mutual combat and the need to protect Serb civilians amid Yugoslavia's dissolution.[37] Independent analyses, such as those from Human Rights Watch, highlight the disproportionate targeting of non-combatants by Serb authorities post-takeover, while noting pre-takeover clashes involved atrocities on multiple sides, though Serb forces held superior organization and firepower in Doboj.[40] These views underscore the war's causal roots in ethno-nationalist mobilization rather than exogenous invasion alone, with source credibility varying: ICTY judgments prioritize forensic and eyewitness evidence over partisan claims, whereas post-war Bosniak reports may amplify victimhood, and Serb accounts minimize perpetrator accountability.Post-War Reconstruction and Recent Events

Following the Dayton Agreement in December 1995, reconstruction in Doboj focused on restoring basic infrastructure damaged during the Bosnian War, with international aid supporting the rebuilding of homes, schools, and bridges amid initial ethnic tensions and hard-line Serb control. Property laws enacted in 1999 facilitated minority returns, enabling over half of the pre-war Bosniak population—estimated at 16,000 to 18,000—to reclaim homes by 2007, though Croat returns remained limited due to employment shortages.[8] In Ševarlije, a Bosniak-majority village in the municipality, approximately 2,000 returnees resettled post-1995, reviving agriculture through a local association with over 200 members, including some Serb farmers, demonstrating localized success in mixed-community revival.[41] Economic recovery progressed through privatizations and foreign investments, with firms like RKTK Doboj (155 employees) and TKS Dalekovod (265 employees) attracting capital by the mid-2000s, alongside plans for a coal-fired power station to position Doboj as an energy hub.[8] Despite these advances, formal employment covered only about 24% of the 82,500 residents in 2007, with 9,700 registered unemployed, reflecting persistent challenges in a mono-ethnic post-war context. Infrastructure efforts included mine clearance from agricultural fields in 2007, a new Bosna River bridge in 2004 linking returnee areas to highways, and the reopening of 16 mosques, community centers, and schools such as the Sevarlije primary school in 2000.[8] In recent years, major transport projects have driven development, including the Banja Luka-Doboj motorway (completed sections by 2022) and the ongoing 14 km Doboj Bypass on Corridor Vc, funded by up to €210 million from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to enhance connectivity with four lanes, interchanges, tunnels, and bridges.[42] Rail rehabilitation on Corridor Vc, including the Doboj-Tuzla-Zvornik line, aims to bolster industrial links, while supervision contracts for 36.6 km of additional motorway extensions were awarded in the early 2020s.[43] These initiatives have spurred regional commerce but faced local complaints over construction impacts like noise and dust since 2022.[44] Social developments include the opening of an early childhood development center in Doboj to aid families, supported by UNICEF amid broader post-pandemic recovery efforts.[45]Demographics

Population Trends and Census Data

The population of Doboj municipality, as recorded in the 1991 census prior to the Bosnian War, stood at 102,549 inhabitants. Following the war's ethnic realignments and territorial divisions under the Dayton Agreement, the municipality's boundaries in Republika Srpska excluded areas assigned to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, reducing the effective pre-war base for comparison.[46] The 2013 census, conducted by the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska Institute of Statistics, enumerated 68,514 residents in Doboj City municipality, reflecting a net decline driven by wartime displacement, postwar refugee returns limited to ethnic Serbs, and ongoing emigration.[47] This figure represented approximately 5.6% of Republika Srpska's total population of 1,228,423 at the time, with a density of about 106 inhabitants per square kilometer across 648 km².[47] Post-2013 estimates indicate further depopulation, with local authorities projecting 60,514 residents in 2017 amid negative natural increase and out-migration to urban centers like Banja Luka or abroad.[48] Independent aggregations place the 2022 figure at 58,305, implying an annual decline rate of roughly 0.62% from 2013 onward, consistent with broader Republika Srpska trends of aging demographics and youth exodus. These reductions underscore causal factors including economic stagnation, low fertility rates below replacement levels, and selective migration patterns favoring opportunities outside Bosnia and Herzegovina.[49]Ethnic Composition and Religious Affiliations

The ethnic composition of Doboj municipality reflects a predominant Serb majority, shaped by historical migrations and the demographic shifts during the Bosnian War (1992–1995), which resulted in the displacement of non-Serb populations and the establishment of ethnically homogeneous areas under Republika Srpska control. According to the 2013 census by the Republika Srpska Institute of Statistics (RZS), out of a total population of 68,514, Serbs accounted for 50,968 individuals or 74.39%, Bosniaks 14,417 or 21.04%, Croats 1,550 or 2.26%, and others 949 or 1.39%, with the remainder undeclared or unknown.[47]| Ethnic Group | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 50,968 | 74.39% |

| Bosniaks | 14,417 | 21.04% |

| Croats | 1,550 | 2.26% |

| Others | 949 | 1.39% |

| Undeclared/Unknown | 630 | 0.92% |

Urban and Rural Settlements

The municipality of Doboj consists of a central urban core centered on the city of Doboj and a network of surrounding rural villages, with the urban population accounting for 26,987 inhabitants or 35% of the total 68,514 residents as per the 2013 census.[50] This urban-rural divide reflects historical shifts, with urban dwellers comprising only 11% of the population in 1948 and rising to 27% by 1991 amid industrialization and internal migration from rural areas.[50] The city proper serves as the administrative, commercial, and transport hub, featuring denser housing, public services, and infrastructure along the Bosna River, while rural settlements predominate in agricultural activities and have experienced net population outflows post-1990s conflict.[50] Doboj municipality encompasses 89 settlements, the vast majority classified as rural villages characterized by dispersed housing, lower population densities, and reliance on farming, forestry, and small-scale trade.[51] These rural areas, totaling 50,236 residents in 2013, cover much of the 648 km² municipal territory and include communities such as those in the Kotarska ispostava Doboj, where 16 settlements housed 8,698 people as of 1921 records, indicative of long-term sparse habitation patterns.[50] Post-war reconfiguration under the Dayton Agreement integrated some adjacent areas into Doboj while separating others into entities like Doboj East and Doboj South, further emphasizing the rural periphery’s isolation from urban amenities.[50] Urban expansion has been limited, with the city core maintaining a population density far exceeding rural averages—approximately 90 inhabitants per km² municipality-wide in recent estimates—driven by rail junctions and light industry rather than broad suburbanization.[5] Rural depopulation persists due to emigration and aging demographics, with 73 local communities (mjesne zajednice) supporting village-level governance amid challenges like underdeveloped roads and services.[51]Economy

Industrial Base and Key Sectors

Doboj's industrial base is anchored in manufacturing sectors such as metal processing, textiles, and food production, bolstered by its strategic position as a transportation hub along Corridor Vc and as the headquarters of the Republika Srpska Railroad Company.[7] The municipality hosts an industrial zone in Usora, spanning 160,000 m² adjacent to the E73 highway, which provides leasing at 3-5 €/m² and incentives including employment subsidies and exemptions from land conversion fees to attract investment.[7] Metal processing constitutes a core sector, with firms like GIP 2 d.o.o., founded in 2007, specializing in the production of forest winches and related metal products.[52] BOSNIA GRAFIT d.o.o., established in 2014 in the Klokotnica industrial area, focuses on graphite-based metalworking operations as a family-owned enterprise.[53] Euro-Metali d.o.o., based in Doboj Jug, engages in trading ferrous metallurgy products and semi-finished goods, supporting downstream manufacturing.[54] Food processing draws on local agricultural resources, including uncontaminated arable land covering 55% of the municipality's 653 km² territory, to process fruits, vegetables, and other raw materials.[7] Bosanka Doboj operates facilities for juice production, pasteurization, and brandy distillation, utilizing high-capacity wells for water supply. Foreign investments, such as Benkons Bosna from Azerbaijan and Bioil from Turkey, have expanded capacity in this sector.[7] Textile production remains a traditional strength, contributing to the local manufacturing profile alongside trade activities.[7] Additional industries include non-metallic minerals processed by Carmeuse (Belgium), plastics manufacturing by Omorika & Rapid P.E.T. (Serbia), and petrochemicals via Nestro Petrol (Russia), diversifying the base beyond primary sectors.[7] As of 2018 data, these activities supported 548 registered companies amid a workforce of 41,594, though high unemployment at 38.05% underscores challenges in scaling employment.[7]Economic Challenges and Growth Indicators

Doboj's economy grapples with structural unemployment and overreliance on traditional industries such as lignite coal mining and metal processing, which expose the municipality to market volatility and environmental regulations amid Bosnia and Herzegovina's EU accession aspirations. In 2013, the unemployment rate in Doboj reached 44%, with 9,764 registered unemployed individuals against 12,480 employed, reflecting persistent post-war labor market distortions and limited job creation outside extractive sectors.[55] Recent regional data from Republika Srpska indicate an official unemployment rate of 9.1% in 2023, though underreporting of informal work and brain drain—driven by low average wages (around 815 BAM net in 2013, equivalent to roughly 415 EUR)—suggest higher effective rates in industrial hubs like Doboj.[56][55] Corruption and inadequate diversification further hinder progress, as political instability in Bosnia and Herzegovina deters foreign direct investment and perpetuates dependence on state-owned enterprises in coal and manufacturing, sectors facing decline due to lignite's high emissions and global energy transitions. Nearby lignite operations, such as the Stanari mine and power plant, provide short-term employment but contribute to environmental degradation and uncertain long-term viability under decarbonization pressures.[57] Growth indicators remain modest, mirroring Republika Srpska's real GDP expansion of 1.9% in 2023, supported by infrastructure investments in Doboj's strategic rail and road networks as a regional transport node.[56] Industrial production in Republika Srpska contracted by 3.2% that year, underscoring challenges in manufacturing, yet opportunities persist in civil engineering and electrical machinery production, with 1,191 active enterprises registered as of 2012.[56][55] Efforts to attract investment in transport and tourism could bolster recovery, though systemic governance issues limit acceleration.[55]Infrastructure and Transportation

Road and Rail Networks

Doboj functions as a pivotal junction in Bosnia and Herzegovina's transportation system, situated along Pan-European Corridor Vc, which integrates key rail and road links for regional and international connectivity.[58] The city's railway infrastructure features the Doboj station, a major hub where the northwest line from Banja Luka intersects the primary north-south route from Bosanski Šamac to Sarajevo, with additional branches extending eastward to Tuzla and Zvornik.[59] This configuration positions Doboj as one of the country's busiest rail nodes, supporting both passenger services and freight transport along Corridor Vc.[60] Rehabilitation efforts have targeted the Bosanski Šamac–Doboj segment (62 km within Republika Srpska) and the adjacent Doboj–Maglaj double-track section (23.5 km), aimed at modernizing infrastructure damaged during the 1990s conflict and improving capacity for cross-border traffic toward Croatia and Serbia.[43][61] The Sarajevo extension from Doboj, originally constructed as a narrow-gauge line, was converted to standard gauge in 1947 to accommodate broader Yugoslav network integration.[62] Road networks converge at Doboj, with the M-17 state road traversing the city as part of European route E73, linking Bosanski Šamac in the north to Zenica and Sarajevo in the south over approximately 100 km from the Croatian border to central Bosnia.[63] Complementing this, the Banja Luka–Doboj motorway—a 76 km, 2x2-lane toll facility—provides a high-capacity western connection, developed in phases since the early 2010s to bypass older routes and integrate with the broader Pan-European network toward Belgrade.[64] Interchanges at Johovac and Rudanka near Doboj facilitate seamless ties between the motorway, M-17, and local roads, supporting economic flows in Republika Srpska despite ongoing maintenance needs on secondary segments like M-4 eastward links.[65] These developments have enhanced Doboj's role in freight and passenger mobility, though electrification and signaling upgrades remain priorities for rail efficiency.[66]Other Infrastructure Developments

Elektroprivreda Republike Srpske (ERS), the public utility of Republika Srpska, submitted an environmental impact assessment request on May 20, 2024, for a 36.3 MW solar photovoltaic power plant on a 64.18-hectare site near Doboj, marking a significant step toward expanding renewable energy capacity in the region.[67][68] The project aligns with broader Republika Srpska goals to integrate up to 250 MW of solar capacity by 2028, amid efforts to reduce reliance on lignite-based generation.[69] A geothermal energy initiative, supported by Czech development assistance, has targeted Doboj municipality to enhance environmental sustainability and living standards through renewable heat sources, though specific implementation timelines remain project-dependent.[70] Existing electrical infrastructure benefits from adequate substation support, facilitating industrial and residential needs without major reported deficiencies as of recent assessments.[71] However, natural gas distribution networks are absent in Doboj, with regional gasification efforts concentrated in eastern Republika Srpska areas rather than the municipality.[71][72] Water and wastewater services are managed by the Municipal Waterworks and Wastewater Utility (MWWU), serving Doboj city and adjacent villages like Lipac and Plane, but no large-scale recent upgrades specific to the area have been documented beyond entity-wide institutional strengthening under World Bank programs.[73]Government and Politics

Local Administration in Republika Srpska

Doboj operates as a city unit of local self-government under the framework of Republika Srpska, as defined by the Law on Local Self-Government of Republika Srpska, which establishes cities and municipalities as primary territorial units with autonomous competencies in local affairs.[74] The city's governance structure includes the City Assembly (Skupština grada Doboj), a unicameral legislative body consisting of councilors elected through proportional representation in local elections held every four years.[75] The assembly holds sessions to adopt decisions on budgets, urban planning, public services, and local development policies, with powers delegated from entity-level authorities but excluding matters reserved for Republika Srpska's government, such as higher education and inter-municipal infrastructure.[74] The executive branch is led by the mayor (gradonačelnik), directly elected by popular vote for a four-year term, who proposes the city budget, appoints administrative heads, and oversees daily operations including utilities, waste management, primary education, and social welfare within the city's jurisdiction.[76] Boris Jerinić, affiliated with the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), has served as mayor since his initial election on February 17, 2019, following premature local elections, and was re-elected in the October 6, 2024, municipal elections.[76][77] The mayor is supported by deputy mayors and a city administration comprising departments for finance, urbanism, economy, and public works, funded primarily through local taxes, entity transfers, and fees generating approximately 80% of the budget from own sources as per standard RS municipal financing models. Local administration in Doboj emphasizes coordination with Republika Srpska's entity government for larger projects, such as road maintenance and environmental protection, while adhering to the principle of subsidiarity wherein decisions are made at the lowest competent level.[74] The city's official website facilitates public access to administrative services, including e-citizen portals for permits and reporting, reflecting efforts to modernize governance amid RS's broader decentralization reforms.[78] Challenges include fiscal dependencies on entity budgets, which accounted for about 20% of revenues in recent years, and occasional political influences on assembly deliberations, though operations remain compliant with RS electoral laws overseen by the Central Election Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[75]Political Dynamics and Controversies

Boris Jerinić, a member of the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), has served as mayor of Doboj since 2020, securing re-election in the October 6, 2024, municipal elections amid competition from candidates of the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) and other local lists.[79][80] Local governance operates within the Republika Srpska entity framework, where executive authority emphasizes entity-level autonomy, including resistance to federal interventions from Sarajevo, aligning with broader RS political stances under President Milorad Dodik.[81] Political competition centers on economic development, infrastructure, and preservation of Serb-majority demographics, with SNSD maintaining dominance through patronage networks and voter mobilization tied to entity loyalty.[82] Doboj's political landscape reflects Republika Srpska's ethno-nationalist orientation, with municipal policies prioritizing Serb cultural institutions and commemorations of 1992 events as defensive actions, often clashing with Bosnian state narratives.[83] Tensions arise from low rates of non-Serb returns post-Dayton Agreement, with the 2013 census recording over 95% Serb population, fueling debates over property restitution and minority integration.[84] Former mayor Obren Petrović (SDS, 2002–2018) faced trial in 2023 for negligence causing public endangerment during 2014 floods, highlighting accountability issues in local administration amid allegations of corruption in reconstruction funds.[85] Controversies stem primarily from the Bosnian War (1992–1995), when Doboj fell under Army of Republika Srpska control in May 1992, leading to documented persecutions, forced displacements, and killings targeting Bosniak and Croat civilians.[86] International and local courts have convicted perpetrators, including for operations involving special units that coerced locals into abuses against non-Serbs; these rulings, from bodies like the ICTY's residual mechanism, underscore systematic patterns despite defenses framing actions as wartime necessities.[87] Nearby Sijekovac saw early 1992 killings of Serb civilians by Croatian and Bosniak forces, cited in Serb political discourse to contextualize subsequent controls, though convictions remain limited.[88] Ongoing disputes involve war crime prosecutions in RS courts, criticized for leniency toward Serb defendants and politicization, exacerbating entity-state frictions.[89]Culture and Society

Education System

Primary education in Doboj, compulsory for children aged 6 to 15 and spanning nine grades, is delivered through public elementary schools such as JU OŠ "Sveti Sava" Doboj, JU OŠ "Dositej Obradović" Doboj (located in the city center with a significant historical role in local schooling), and JU OŠ "Vuk Stefanović Karadžić" Doboj.[90] [91] [92] Enrollment trends reflect demographic decline, with 461 first-grade pupils registered for the 2025/2026 school year across Doboj's primaries—an increase of 29 from the prior year—yet some rural branches report critically low numbers, including three schools with no first graders in 2023 and four without in 2024.[93] [94] [95] Secondary education, lasting four years post-primary, encompasses general and vocational programs in institutions like Gimnazija "Jovan Dučić" Doboj (offering general, social-linguistic, and computer-informatics tracks), Medicinska škola Doboj, Ekonomska škola Doboj (enrolling 110 first-year students in 2025), Tehnička škola Doboj, and JU Saobraćajna i elektro škola Doboj (with 683 pupils across 25 classes as of recent data).[96] [97] [98] [99] The Doboj region hosts about 15 secondary schools serving roughly 1,500 students annually.[100] Higher education in Doboj includes the private College of Business and Technology of Doboj (Visoka poslovno-tehnička škola Doboj), offering bachelor's programs in business and technical fields; a campus of Slobomir P University; and the Faculty of Transport and Traffic Engineering Doboj, affiliated with the University of East Sarajevo, established from a local polytechnic initiative.[101] [102] [103] [104] Doboj serves as a regional hub for post-secondary options, though overall enrollment remains modest amid broader Republika Srpska challenges like population outflow.[105] Recent developments include the July 2025 opening of an Early Childhood Development Centre in Doboj, providing multidisciplinary early intervention for children aged 0-6 to address developmental needs in a region facing poverty and deprivation risks.[106][107]Sports and Recreation

Football dominates organized sports in Doboj, with FK Sloga Doboj competing in the Premier League of Bosnia and Herzegovina and hosting matches at Stadion Luke, which has a capacity of 3,000 spectators.[108] The club maintains a youth academy focused on developing young players through non-competitive training programs.[109] Another local team, FK Željezničar Doboj, participates in regional leagues. Futsal is represented by KMF Doboj, active in national competitions.[110] Basketball has produced notable talent, including Ognjen Kuzmić, born in Doboj on May 16, 1990, who played as a center in the NBA for the Golden State Warriors after being drafted in 2012 and later represented Serbia internationally.[111] Other disciplines include badminton through Sertini Club, which promotes the Olympic sport across youth and competitive categories; taekwondo via the local club; and kickboxing at Predator Combat Academy.[112] [113] [114] Recreational activities center on outdoor pursuits, with paragliding supported by ParaGhost Club, established in 2009 and affiliated with the World Air Sports Federation, offering flights over the Ozren mountains.[115] Urban facilities like Sport-Park Rudanka provide indoor football pitches, a gym, and recreational spaces.[116] Parks such as Park Narodnih Heroja offer green areas for leisure, while nearby Goransko Jezero enables swimming and fishing.[117]Cultural Symbols and Heritage

The official symbols of Doboj include its flag and coat of arms, which represent the city's identity within Republika Srpska. The flag features a design incorporating elements of local and regional heritage, while the coat of arms, adopted in 1995, consists of a golden shield notched with four firesteel-shaped indentations and divided into four fields symbolizing historical attributes of the region.[118] These emblems are used in official capacities to denote municipal authority and cultural continuity. Doboj's primary cultural heritage site is the Doboj Fortress, known as Gradina, constructed in the 12th century and recognized as a national monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina due to its architectural and historical value. Originally a royal property of the Kotromanić dynasty, the fortress served as a defensive stronghold overlooking key trade routes and has been destroyed and rebuilt at least 18 times, underscoring its enduring significance as a symbol of resilience amid invasions and conflicts.[10][9][119] Today, it hosts cultural events, including an ethno café, and is promoted as a key asset for tourism and preservation of medieval Bosnian heritage.[120][121] The Regional Museum of Doboj preserves artifacts spanning from the Stone Age to the early Ottoman period, with an archaeological collection exceeding 10,000 items that document prehistoric settlements, Roman influences, and medieval developments in the area. This institution contributes to the safeguarding and public education on Doboj's layered cultural history, emphasizing empirical archaeological evidence over narrative interpretations.[122] Annual events such as the International Tourism Festival (FESTTOUR), held in June at the fortress, highlight local traditions through exhibitions of crafts, music, and cuisine, fostering community engagement with heritage elements rooted in Bosnian-Serb customs.[120]Notable Sites and Landmarks

The Doboj Fortress, also known as Dobojska Tvrđava Gradina, is a medieval fortification constructed in the early 13th century as one of the primary defenses in the Banate of Usora.[20] Initially built as a wooden structure, it was rebuilt in stone during the early 15th century following the Battle of Doboj in 1415, where Bosnian nobility allied with Ottoman forces against Hungarian invaders.[11] The fortress features ruined walls and towers that provide panoramic views of the surrounding Usora valley, and its architectural elements reflect a blend of medieval Bosnian and later Ottoman influences, with significant reconstructions in the 17th century.[9] Designated as a national monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina, it remains a key historical site attracting visitors for its role in regional defense and turbulent history spanning centuries of conflict.[123] Other notable landmarks include the Doboj Regional Museum, which houses exhibits on local history, ethnography, and archaeology from the Roman era through the Ottoman and Yugoslav periods, including artifacts from nearby ancient settlements.[124] The Park of National Heroes (Park Narodnih Heroja) serves as a commemorative green space honoring figures from World War II and the Bosnian War, featuring monuments and memorials amid landscaped grounds central to the city's public life.[117] Nearby natural attractions like Goransko Lake offer recreational opportunities, though they are secondary to the fortress in historical significance.[117]Notable Individuals

Silvana Armenulić (May 18, 1939 – October 10, 1976), born Zilha Bajraktarević in Doboj, was a renowned Yugoslav folk singer whose career spanned recordings and performances across the region until her death in a car accident.[125] Ognjen Kuzmić (born May 16, 1990), a professional basketball center born in Doboj, played in the NBA for the Golden State Warriors and represented Serbia internationally, accumulating experience in European leagues including Crvena zvezda.[111][126] Enis Bešlagić (born January 6, 1975) is a Bosnian actor from Doboj, known for roles in films like Fuse (2003) and television series such as Naša mala klinika, establishing a career in Bosnian cinema and theater.[127] Aleksandar Đurić (born August 12, 1970), a striker born in Doboj, competed for Singapore's national team after naturalization in 2007, scoring over 400 goals in Singaporean leagues and representing Bosnia in canoeing at the 1992 Olympics.[128] Borislav Paravac (born February 18, 1943), raised near Doboj and serving as its mayor from 1990 to 2000, held the position of Serb member of Bosnia and Herzegovina's presidency from 2003 to 2006.[129]International Ties

Twin Cities and Partnerships

Doboj maintains formal twin city partnerships with Celje in Slovenia, established in 1965, and Ćuprija in Serbia.[130] These relationships promote exchanges in cultural, economic, and administrative domains, reflecting historical ties from the Yugoslav era. Celje, the fourth-largest city in Slovenia and administrative center of the Savinja region, provided humanitarian assistance to Doboj during the 2014 floods, including personnel deployment, financial contributions, and material supplies.[130] The partnership with Ćuprija, a municipality in Serbia's Pomoravlje District with a population of 19,471 as of the 2011 census, emphasizes regional connectivity, given Ćuprija's position along major transport routes between Belgrade and Niš.[130] No additional international partnerships or cooperative agreements beyond these twin cities are formally documented by municipal authorities.[130]References

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Doboj