Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dutch Colonial Revival architecture

View on Wikipedia

Dutch Colonial Revival is a style of domestic architecture, primarily characterized by gambrel roofs having curved eaves along the length of the house. Modern versions built in the early 20th century are more accurately referred to as "Dutch Colonial Revival", a subtype of the Colonial Revival style.

History

[edit]

The modern use of the term is to indicate a broad gambrel roof with flaring eaves that extend over the long sides, resembling a barn in construction.[1] The early houses built by settlers were often a single room, with additions added to either end (or short side) and very often a porch along both long sides. Typically, walls were made of stone and a chimney was located on one or both ends. Common were double-hung sash windows with outward swinging wood shutters and a central double Dutch door.

Settlers of the Dutch colonies in New York, Delaware, New Jersey, and western Connecticut built these homes in ways familiar to the regions of Europe from which they came, like the Low Countries, the Palatine parts of Germany, and Huguenot regions of France.[2] Used for its modern meaning of "gambrel-roofed house", the term does not reflect the fact that housing styles in Dutch-founded communities in New York evolved over time. In the Hudson Valley, for example, the use of brick, or brick and stone is perhaps more characteristic of Dutch Colonial houses than is their use of a gambrel roof. In Albany and Ulster Counties, frame houses were almost unknown before 1776, while in Dutchess and Westchester Counties, the presence of a greater proportion of settlers with English roots popularised more construction of wood-frame houses.[3]: 22 After a period of log cabin and bank-dugout construction, the use of the inverted "V" roof shape was common. The gambrel roof was used later, predominantly between 1725 and 1775, although examples can be found from as early as 1705.[3]: 23 The general rule before 1776 was to build houses that were only one-and-a-half stories high, except in Albany, where there were a greater proportion of two-story houses. Fine examples of these houses can be found today, like those in the Huguenot Street Historic District of New Paltz, New York.

In the American colonies both the Dutch and Germans plus others along the Rhine region of Europe contributed to the Dutch fashion. Three easily accessible examples of Dutch (Netherlands or German) architecture can be seen; 1+1⁄2-story 1676 Jan Martense Schenck House in the Brooklyn Museum, 1+1⁄2-story 1730s Schenck House located in the "Old Beth Page" Historic Village, and the two-story 1808 Gideon Tucker House at No. 2 White St at Broadway in Manhattan. All three represent distinctly Dutch (Netherlands-German) styles using "H-frame" for construction, wood clapboard, large rooms, double hung windows, off set front entry doors, sharply sloped roofs, and large "open" fireplaces. Often there is a hipped roof, or curved eves, but not always. Barns in the Dutch-German fashion share the same attributes.[4][5][6]

Examples of hipped and not hipped roofs can be seen on the three examples provided above. The 1676 and 1730 Schenck houses are examples of Dutch houses with "H-frame" construction but without the "hipped" roof. The 1730 Schenck house has the distinctive "curved eves". Hips can be in a few different styles. The more common being a Mansard as known in Europe or "gambrel" as known in American English, both having two slopes on at least two sides. The Gideon Tucker (though an older Englishman) choose to build his house with a gambrel roof and in an urban Dutch-German fashion.

Revival in the 20th century

[edit]

Beginning in the late 19th century, America began to look back romantically upon its colonial roots and the country started reflecting this nostalgia in its architecture. Within this Colonial Revival, one of the more popular designs was a redux of features of the original Dutch Colonial. The term "Dutch Colonial" appeared sometime between 1920 and 1925.[7]

Within the context of architectural history, the more modern style is specifically defined as "Dutch Colonial Revival" to distinguish it from the original Dutch Colonial. However, this style was popularly known simply as Dutch Colonial, and this continues to be the case today. In New York, for instance, the actual 17th-century colonial architecture of New Amsterdam has completely vanished (lost in the fires of 1776 and 1835), leaving only archaeological remnants.[8][9]

Up and through the 1930s, Dutch Colonials were most popular in the Northeast. While the original design was always reflected, some details were updated such as the primary entryway moving from the end to the long side of the house. The more modern versions also varied a great deal with regard to materials used, architectural details, and size. For example, one Dutch Colonial might be a small two-story structure of 1,400 square feet (130 m2) with dormers bearing shed-like overhangs, while another larger example would have three stories and a grand entrance adorned with a transom and sidelights.

Buildings

[edit]Examples of urban style of Dutch Colonial Revival architecture can be found in Manhattan, New York. 57 Stone Street was rebuilt in 1903 by C. P. H. Gilbert on behest of the owner Amos F. Eno. The buildings to the back on South William Street 13–23 also were reconstructed in the Dutch revival style, evoking New Amsterdam with the use of red brick as building material and the features of stepped gables.[10] Stepped gables on early 20th-century Dutch Revival buildings on S William Street in Lower Manhattan recall the Dutch origins of the city. The area was declared a historic district in 1996 by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[11]

The Children's Aid Society had a number of its centers constructed in the Dutch colonial revival style, such as the Rhinelander Children's Center at 350 East 88th Street, the 6th Street Industrial School on 630 East 6th Street, the Fourteenth Ward Industrial School at 256–258 Mott Street, and the Elizabeth Home for Girls at 307 East 12th Street.

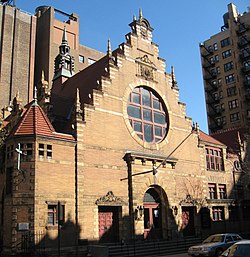

West End Avenue saw a large number of buildings designed in the Dutch colonial revival style. The West End Collegiate Church was modelled after the Vleeshal at the Grote Markt in Haarlem.[12]

Further examples in New York City are the former George S. Bowdoin Stable at 149 East 38th Street, 119 West 81st Street, and 18 West 37th Street.[13]

An industrial example was the Wallabout Market, designed by the architect William Tubby and constructed in 1894–1896. They were demolished in 1941 during World War II.

Sunnyside in Tarrytown, New York, was partly constructed in Dutch Colonial revival.

112 Ocean Avenue, a Dutch Colonial home, became infamous as the site of the "Amityville Horror".

Images

[edit]-

Fourteenth Ward Industrial School of the Children's Aid Society at 256–258 Mott Street in New York, 1888–1889

-

George S. Bowdoin Stable at 149 East 38th Street in New York, 1902

-

Holland Apartments, 324–326 N. Vermilion Street in Danville, Illinois, 1906

-

House in Plainfield, New Jersey

-

William E. Curtis House in Tampa, Florida, 1905–1906

-

Central School (Iron River, Michigan), 1911–1919

-

57 Stone Street, NYC

-

Flagler Residence, 1905, demolished in 1953

-

Widow Sturtevant House in Albany, c1933

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Dutch Colonial". Realtor Mag. May 1, 2001. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.),Exploring Historic Dutch New York. Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, New York 2011

- ^ a b Helen Wilkinson Reynolds, Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley Before 1776, Payson and Clarke Ltd. for the Holland Society of New York, 1929. Reprinted by Dover Publications Inc. 1965.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org.

- ^ "Old Bethpage Village Restoration by James Robertson". PBase.

- ^ "WEST BROADWAY Part 2 – Forgotten New York". forgotten-ny.com. 5 May 2008.

- ^ "Dutch Colonial". Dictionary.com. 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ "Map of Great Fire 1776". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2006. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ "Great Fire of 1835: Aftermath". Virtual New York. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (December 27, 2012). "A Nod to New Amsterdam". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Breiner, David M. (June 25, 1996). "Stone Street Historic District: designation report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (January 30, 2009). "The School of the Stepped Gables". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ "Why are these Dutch-style houses on 37th Street?". Ephemeral New York. March 22, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Mitchell, Sarah E. (2007). "Colonial Homes with Gambrel Roofs". vintagedesigns.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

Dutch Colonial Revival architecture

View on GrokipediaOrigins in Colonial America

Early Dutch Settlements

The Dutch West India Company sponsored the initial colonization of New Netherland beginning in 1624, when the first permanent settlers arrived from the Netherlands and established outposts along the Hudson River and surrounding areas, encompassing present-day New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and parts of Connecticut.[4] Key early settlements included New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, founded in 1625-1626 as the colony's administrative and commercial center; Fort Orange near present-day Albany, established in 1624 as a fur trading post; and New Paltz in Ulster County, settled in 1677-1678 by a group of French Huguenots under Dutch governance.[5][6] These locations served as anchors for expansion, with colonists securing land through purchases from Indigenous groups and patroonship grants that encouraged agricultural development.[7] The settler population in New Netherland was diverse, drawing primarily from the Low Countries—including Dutch from the Netherlands and Flemish/Walloon speakers from modern-day Belgium—but also incorporating Palatine Germans who arrived in waves starting in the early 1700s and French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution. This mix influenced building traditions, blending Dutch vernacular practices like sturdy, practical farmhouses with German half-timbering elements and Huguenot adaptations for communal stone structures in areas like New Paltz.[8] The resulting architecture reflected a synthesis suited to the colonial environment, prioritizing durability over ornamentation. Early construction in these settlements relied on locally available materials and techniques adapted to the region's climate and resources, featuring wood framing for flexibility in seismic-prone areas and extensive use of Hudson Valley bluestone for foundations and walls to withstand harsh winters and flooding.[9] One-and-a-half-story homes predominated, providing efficient living space under low ceilings while allowing for steep roofs to shed heavy snow; these designs often incorporated post-and-beam framing filled with brick nogging or wattle-and-daub for insulation.[10] Following the English conquest of New Netherland in 1664, architectural styles evolved through blending with English traditions, including the adoption of gambrel roofs in late 17th- and early 18th-century structures to enable greater attic storage for grain and goods.[11][12] Surviving examples illustrate these practices, such as the Jan Martense Schenck House in Brooklyn, constructed around 1676 by settler Jan Martense Schenck as a one-and-a-half-story wood-framed dwelling with a central chimney, representing one of the oldest intact Dutch colonial structures in the United States.[13] Similarly, the Schenck House in Old Bethpage, built in the 1730s, exemplifies later refinements with its stone foundation and compact layout, relocated to preserve its representation of rural Dutch farm life.[8] Socio-economic conditions in New Netherland drove the development of compact, functional designs, as the colony's economy centered on fur trade hubs like New Amsterdam and Fort Orange, alongside expansive farms under the patroonship system that supplied grain, livestock, and timber to European markets.[14] These factors necessitated versatile buildings that doubled as residences, storage, and workshops, with small footprints to maximize arable land on family holdings amid labor shortages and frontier uncertainties.[15]Key Architectural Influences

The original Dutch Colonial style in America drew heavily from the architectural traditions of the Low Countries, particularly the Netherlands and Belgium, where steep roofs were a hallmark of Dutch Renaissance designs adapted for practical needs like shedding heavy snow loads in northern European climates. These influences manifested in steeply pitched gable roofs, which carried over to colonial settlements in New Netherland to handle the region's winter precipitation.[11][16] Additionally, features such as the H-bent timber framing system—consisting of anchor bents with posts connected by tie beams—and jambless fireplaces with open hearths reflected medieval Dutch vernacular forms that emphasized functionality and fire safety in wooden structures.[16][11] Palatine German immigrants from the Rhineland region contributed significantly to the style's evolution, introducing half-timbering techniques and robust stone masonry that blended with Dutch forms in the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys. These settlers, arriving in waves around 1709–1710, brought expertise in constructing durable fieldstone walls and timber-framed barns, which enhanced the stability of colonial farmhouses against harsh American weather.[17][18] Their influence is evident in structures like those in the Mohawk Valley, where German-style masonry integrated with Dutch gable roofs to create hybrid buildings suited to agricultural life.[19] French Huguenot settlers in areas like New Paltz incorporated elements of symmetrical facades and orderly interior layouts, drawing from their Protestant French heritage while adopting dominant Dutch construction methods due to the colonial context. In the Huguenot Street Historic District, established from 1678 onward, stone houses built by families such as the Hasbroucks around 1712–1721 showcase this blend, with balanced front elevations and Dutch steep roofs reflecting cultural exchanges among European immigrants.[20] Adaptations to the New World environment further shaped the style, as settlers shifted from imported Dutch bricks—scarce and expensive—to abundant local materials like fieldstone quarried from Hudson Valley sites and native timber for framing, evolving medieval European farmhouse designs into practical colonial necessities. This period of peak integration, roughly 1725–1775, saw these influences coalesce in rural settings, prioritizing durability and ventilation through features like extended eaves over traditional stoops.[11][21] The Huguenot Street Historic District exemplifies this synthesis, with its early stone dwellings illustrating how Dutch, German, and French traditions merged to meet American agrarian demands.[20]Defining Characteristics

Roof and Structural Elements

The gambrel roof serves as the defining structural feature of Dutch Colonial Revival architecture, characterized by two slopes on each side of the roof—a steeper lower slope transitioning to a shallower upper slope—often with curved or flared eaves that extend along the length of the house.[22][1] This design, drawing briefly from original Dutch colonial influences in early American settlements, creates a symmetrical, barn-like profile that visually breaks the mass of the structure into a more approachable scale.[23] The configuration typically employs a side-gabled (flank-gambrel) form on one-and-a-half-story homes, where the gambrel effectively adds a full second story within the attic space without increasing the building's height dramatically.[1] Historically, the gambrel roof originated in Dutch barn designs to maximize hay storage and loft space by allowing a wider span under a lower overall height, a functional adaptation later applied to residential attics in the Revival period for expanded living areas and efficient water runoff.[24][22] Eaves provide shade and protection while enhancing the roof's aesthetic flow.[25] Supporting elements include shed-style dormers that pierce the roof surface, often in a continuous full-width form on the front elevation or as separate units, to admit natural light and additional headroom in the upper story.[1][26] Construction materials emphasize durability and regional availability, with roofs commonly covered in wood shingles or slate for weather resistance and a textured appearance that complements the style's rustic origins.[25][22] Below, walls are typically clad in wood siding such as clapboard or shingles, though brick or stone was used in some examples, while chimneys are integrated into the gable ends to provide functional ventilation.[27][28] Variations in scale reflect the Revival's adaptability, ranging from modest one-and-a-half-story homes around 1,400 square feet to larger three-story examples that maintain the gambrel profile for grandeur without altering core proportions.[29] These elements collectively ensure the style's practicality, with the gambrel's dual slopes optimizing interior volume while the robust framing withstands environmental demands.[30]Windows, Doors, and Facades

In Dutch Colonial Revival architecture, windows are a key element of the facade's balanced aesthetic, typically featuring multi-pane double-hung sashes arranged symmetrically across the front elevation. Common configurations include 6-over-6, 8-over-8, or 9-over-6 arrangements, with the upper and lower sashes divided by muntins to evoke the proportions of 18th-century colonial prototypes while allowing for practical operation.[31][32] These windows are often paired or arranged in triplets, flanked by louvered shutters, and topped with straight heads or pediments to enhance the classical symmetry. Additionally, small oval or bull's-eye windows are frequently incorporated into the gable ends, providing ventilation and subtle ornamentation without disrupting the overall restraint of the design.[23][32] Doors in this style emphasize functionality and historical reference, with the iconic Dutch door—split horizontally into independent upper and lower halves—serving as a hallmark feature that allows for ventilation while maintaining security. These paneled wooden doors, often heavy and robust, are centered on the facade and may be surmounted by transoms or fanlights to admit natural light into the entry hall.[33][31] Flanking sidelights, typically narrow and multi-paned, frame the entrance to integrate interior spaces with the exterior, drawing light into central hallways that connect to the home's core chimney structure. In revival interpretations, door hardware is often simplified compared to ornate originals, favoring clean pedimented surrounds or pilasters for a streamlined classical effect.[31][32] Facades of Dutch Colonial Revival buildings achieve cohesion through symmetrical layouts, with a central entrance anchoring a five-bay composition of evenly spaced windows and doors. Exteriors are clad in wide clapboard siding, wood shingles, or occasionally roughcast stucco, providing a textured surface that contrasts with the smooth lines of surrounding elements. Front porches, sheltered under the broad overhanging eaves of the gambrel roof, frequently feature classical columns and balustrades, extending the facade's hospitality while framing the entry. Revival-era adaptations incorporated modern glass in window sashes for enhanced clarity and light transmission, though traditional muntin divisions were retained to preserve the style's colonial authenticity.[32][1][23]The Revival Movement

Emergence in the Late 19th Century

The Dutch Colonial Revival emerged as a subset of the broader Colonial Revival movement, which spanned from the 1880s to the 1940s and represented a reaction against the ornate industrialization of Victorian architecture, favoring instead a return to perceived simplicity and authenticity in American colonial forms. This resurgence was catalyzed by major cultural events that heightened national interest in early American history, including the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which showcased recreated colonial buildings and furnishings to celebrate the nation's founding, and the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where neoclassical structures evoked a sense of historical grandeur and inspired architects to draw from pre-industrial precedents.[34][31][35] The specific term "Dutch Colonial" for this revival style began to appear in architectural discourse around the 1890s, as historians and architects distinguished it from other colonial variants by its emphasis on gambrel roofs and regional Dutch influences from the 17th and 18th centuries. Early adopters included prominent figures like Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert, who in 1903 redesigned the facade at 57 Stone Street in Manhattan's Financial District in a Neo-Dutch Renaissance style, featuring stepped gables, brickwork, and curved eaves to evoke New Amsterdam's heritage; this project, commissioned by real estate investor Amos F. Eno, marked one of the earliest urban applications of the style. The earliest known residential examples date to circa 1895, such as the Taft House in Granada Hills, California, which integrated Dutch elements into emerging suburban contexts.[36][37] Socio-cultural factors driving this emergence included a post-Civil War nostalgia for unified American roots, as the nation sought to heal divisions through romanticized visions of its colonial past, particularly in the Northeast where Dutch settlements had left a lasting imprint. This sentiment fueled restorations in the Hudson Valley, where surviving 18th-century structures inspired renewed appreciation for vernacular forms amid rapid urbanization. Initial adaptations often incorporated the signature gambrel roof—allowing for expanded attic space—into Victorian or Shingle Style frameworks, making the style accessible for middle-class suburban homes in areas like New York and New Jersey, where it symbolized practicality and historical continuity.[38][39][37]Peak and Decline in the 20th Century

The Dutch Colonial Revival style reached its zenith between 1910 and 1930, emerging as a prominent variant of the broader Colonial Revival movement and gaining widespread adoption in suburban residential construction across the Northeastern United States. During this period, the style's characteristic gambrel roofs and practical layouts appealed to middle-class homeowners seeking affordable yet aesthetically pleasing designs, with thousands of examples built through both custom commissions and prefabricated kits. Mail-order catalogs from companies like Sears, Roebuck and Company played a pivotal role in its dissemination, offering models such as the Puritan and Verona that accounted for a significant portion of kit homes; estimates suggest Colonial Revival styles, including Dutch variants, comprised about 40% of new residential builds in the 1920s, particularly in regions like New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.[40][41][42] Influential architects and media further propelled the style's popularity. Early examples, such as Frank Lloyd Wright's Bagley House in Minneapolis (1894), demonstrated its adaptability in custom designs, blending traditional elements with emerging Prairie influences to inspire later 20th-century iterations. Magazines like House Beautiful promoted the style through features on exemplary homes, such as the Roger Taft House in Belmont, Massachusetts (1915), which highlighted its compact efficiency and charm for modern living. This promotion, combined with a cultural nostalgia for colonial heritage amid rapid urbanization, ensured the style's prominence in suburban developments in the Northeast during the 1920s.[43][42] The style's decline began in the 1930s, accelerated by the Great Depression, which drastically curtailed custom home construction and shifted priorities toward utilitarian designs under federal programs like the Works Progress Administration. The rise of Modernism, with its emphasis on functionalism and rejection of historical ornamentation, further marginalized revival styles post-1930, as architects like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe advocated for sleek, machine-age aesthetics that gained traction in institutional and residential projects. By the 1940s and 1950s, the Ranch style supplanted Dutch Colonial Revival in suburban expansions, favoring single-story layouts suited to post-World War II automobile culture, though remnants persisted in restorations and select planned communities inspired by earlier catalog designs.[44][45][46]Regional Variations and Adaptations

Northeastern United States

The Dutch Colonial Revival style found its strongest expression in the Northeastern United States, particularly in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, where the majority of surviving examples are located due to the region's direct historical connections to the 17th-century New Netherland colony established by Dutch settlers.[34] These states encompass the core of the original Dutch settlements, fostering a revival that drew on local nostalgia for colonial-era buildings during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[31] The style's prevalence here reflects broader national trends in the Colonial Revival movement, which emphasized American heritage amid rapid industrialization.[34] In urban settings, such as Manhattan, the style adapted to denser environments through rowhouses featuring brick facades that evoked Dutch commercial architecture while meeting modern needs. A notable cluster appears in the Stone Street Historic District, where buildings like 13 South William Street, reconstructed in 1903 by architect C.P.H. Gilbert, incorporate neo-Dutch Renaissance elements including stepped gables and honey-colored Roman brick with limestone trim.[36] These adaptations maintained the gambrel roof's silhouette but scaled it for rowhouse configurations, blending historical references with practical urban density.[36] Suburban applications proliferated in areas like the Hudson Valley, where local materials enhanced regional authenticity, including bluestone foundations common in New York for their durability against the area's rocky terrain and shingle roofs in coastal zones of New Jersey and Long Island for weather resistance.[47] Developments in Westchester County, New York, and parts of Long Island integrated Dutch Colonial Revival homes into neighborhoods alongside other Colonial Revival styles, creating cohesive suburban enclaves that celebrated local history.[48] Preservation efforts have played a crucial role in maintaining these structures, particularly through historic districts like Sleepy Hollow in Westchester County, where organizations such as Historic Hudson Valley safeguard sites with Dutch influences, ensuring the style's integration into broader colonial heritage narratives.[48] These initiatives highlight the architectural legacy's ties to early Dutch settlements, protecting examples that might otherwise succumb to development pressures.Other Regions

While the Dutch Colonial Revival style originated and flourished predominantly in the Northeastern United States, its diffusion to other regions involved significant adaptations to local climates, materials, and landscapes, often resulting in hybrid forms that deviated from traditional designs.[49] In the Midwest, particularly around Chicago, early examples emerged in the late 19th century, influenced by architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, who incorporated gambrel roofs and flared eaves into his initial residential works before transitioning to Prairie style.[43] The 1894 Bagley House in Hinsdale, Illinois, exemplifies this, featuring a dormered gambrel roof and columned veranda that blended Dutch Revival elements with Midwestern practicality for flatter terrains.[43] Further west in Wisconsin, such as in Marshfield, gambrel-roofed structures reflected Dutch influences adapted with local wood framing to suit expansive prairies.[50] In the South, implementations were rare during the 1920s, primarily limited to suburban areas, where the style clashed with humid climates and vernacular preferences for raised foundations and wide porches.[51] Examples incorporated gambrel roofs but often hybridized with broader Colonial Revival motifs to better accommodate heat and moisture, though they remained outliers amid dominant Spanish and Greek Revival traditions.[51] Western adaptations, such as in California, substituted traditional stone or brick with stucco finishes to endure arid conditions and seismic activity, creating lighter, more Mediterranean-inflected versions seen in Los Angeles suburbs during the interwar period.[52] In the Southwest, hybrids merged Dutch gambrel forms with Spanish Revival tile roofs and adobe-like walls, addressing both aesthetic continuity and regional durability needs.[52] The gambrel roof's broad eaves and steep pitch posed practical challenges in hurricane-prone Southern and coastal areas, where high winds could stress the structure without reinforcements, leading to limited adoption and frequent modifications like clipped ends or lower profiles.[53] In arid Western environments, the style's reliance on shingled or clapboard siding required adjustments to prevent cracking from dry heat, further encouraging material substitutions.[53] Notable outliers include Colorado, where the style gained modest traction from 1900 to 1925, primarily in residential forms with prominent gambrel roofs suited to the state's varied elevations, as documented by History Colorado in Denver examples.[54] In the Pacific Northwest, adaptations featured cedar siding for weather resistance, evident in Seattle's 1915 Dutch Colonials that integrated the gambrel silhouette with regional timber aesthetics.[55] The style's 20th-century spread to the Midwest and South was facilitated by mail-order catalogs from companies like Sears and Aladdin, which offered pre-cut Dutch Revival kits from 1900 to the 1930s, enabling affordable construction in non-traditional areas despite comprising a small fraction of overall housing stock.[56]Notable Examples

Residential Buildings

Residential buildings in the Dutch Colonial Revival style typically featured private homes that evoked the simplicity and functionality of early Dutch settler architecture, adapted for suburban and rural American living during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[27] These structures often served as family dwellings, emphasizing symmetry, practicality, and a connection to historical roots amid the broader revival movement that romanticized colonial pasts.[57] One early and iconic example is Sunnyside in Tarrytown, New York, the home of author Washington Irving, constructed and expanded between 1835 and the 1850s.[58] The residence showcases key Dutch Colonial Revival elements, including a gambrel roof with dormers that allow for additional attic space, blended with whimsical Gothic and Tudor influences to create a picturesque cottage-like estate along the Hudson River.[58] Restored and preserved as a historic site, Sunnyside stands as an early exemplar of the style's revival, highlighting its role in popularizing romanticized colonial forms for elite literary figures.[58] In the 1920s, high-end suburban homes like 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, New York, built in 1925, exemplified the style's adaptation for affluent waterfront living.[57] This three-story, 3,600-square-foot residence features a gambrel roof with curved eaves extending over a prominent porch, providing shade and a welcoming entry typical of the period's domestic designs.[59] Its cultural notoriety stems from the 1977 book and subsequent film The Amityville Horror, which brought widespread attention to this otherwise conventional Dutch Colonial Revival home.[57] Frank Lloyd Wright's Warren McArthur House, completed in 1892 in Chicago's Kenwood neighborhood, represents an early professional interpretation of the style through a "bootleg" commission outside his firm duties.[60] The 3,852-square-foot structure incorporates a dormered gambrel roof and octagonal bays, integrating seamlessly with its landscaped surroundings in line with Wright's emerging organic principles.[60][61] This design bridged traditional revival motifs with modern spatial flow, influencing later residential architecture.[60] Sears, Roebuck and Company's catalog homes from the 1910s to 1920s democratized the style for middle-class buyers via prefabricated kits, with models like the Alhambra offering accessible interpretations.[62] The Alhambra, a two-story Dutch Colonial Revival plan with a gambrel roof, spanned approximately 2,280 square feet and included standard features like stucco siding, allowing owners to assemble durable, historically inspired homes affordably.[63] Common traits among these residential examples include sizes ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 square feet, central hallways for efficient circulation, and multiple built-in fireplaces that served as focal points for family gatherings, enhancing both functionality and warmth in the home's interior layout.[64][27]Institutional and Public Structures

Dutch Colonial Revival architecture extended beyond private homes to institutional and public structures, where its distinctive features—such as gambrel roofs and stepped gables—were scaled up to accommodate communal functions and evoke historical ties to early Dutch settlements in the Northeast. These buildings often served as anchors for community identity, blending revivalist aesthetics with practical needs for worship, education, and civic engagement.[65][36] A prominent example is the West End Collegiate Church in New York City, completed in 1892 under the design of architect Robert W. Gibson. This structure features a steep gambrel roof and a prominent stepped gable with Baroque finials, drawing direct inspiration from the 1606 Vleeshal in Haarlem, Netherlands, while incorporating Gothic interior elements like carved oak furnishings in an Old Dutch style. The church's facade uses long, thin Roman-pattern brown bricks with buff terra-cotta trim, creating a picturesque blend of Renaissance Revival decoration and Dutch Colonial Revival form that reflected the congregation's Dutch heritage amid the Upper West Side's urban development.[65][66] The Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, New York, originally constructed in 1697 of local fieldstone, exemplifies an early Dutch Colonial prototype. Following a fire in 1837, repairs relocated the main entrance and maintained the building's thick stone walls and gambrel roof, with later interior restorations in the mid-20th century restoring exposed beams and quartered oak ceilings to evoke the original Dutch simplicity. These efforts preserved the church's historical character, reinforcing its role as an enduring symbol of Dutch colonial legacy in the Hudson Valley and an inspiration for later Revival architecture.[67][68] In urban settings, the Stone Street Historic District in Manhattan includes commercial-residential buildings redesigned by architect C.P.H. Gilbert starting in 1903 for owner Amos F. Eno. At 57 Stone Street (also known as 13 South William Street), Gilbert employed neo-Dutch Renaissance styling—closely aligned with Dutch Colonial Revival—featuring honey-colored Roman brick with limestone trim, a stepped gable, and decorative ironwork on a five-story facade that unified the row with gambrel-inspired rooflines and bull's-eye windows. This project transformed older mercantile structures into cohesive office spaces, highlighting the style's adaptability for public commercial use while nodding to Manhattan's Dutch founding.[36] Educational and library institutions in the Hudson Valley and New Jersey also embraced Dutch Colonial Revival during the 1920s to foster a sense of historical continuity. These buildings typically featured larger footprints exceeding 5,000 square feet, with expansive communal interiors sheltered under broad gambrel roofs to support gatherings and educational activities, distinguishing them from the more intimate scale of residential applications.[69][70]Legacy and Modern Influence

Impact on American Architecture

The Dutch Colonial Revival style played a significant role within the broader Colonial Revival movement, emerging as a subtype that emphasized regional American architectural traditions rooted in early Dutch settlements along the Hudson River Valley. By reviving the distinctive gambrel roof with flared eaves, the style contributed to the popularization of localized colonial forms, distinguishing it from more generalized Georgian or Federal influences. This focus on authenticity helped diversify the Colonial Revival's palette, making it a key element in suburban developments during the early 20th century, where it symbolized a return to perceived "original" American domesticity amid rapid urbanization.[34][71] In terms of preservation, the revival spurred renewed interest in original 17th- and 18th-century Dutch Colonial structures, particularly in areas like New Paltz, New York. Organizations such as Historic Huguenot Street, established in 1894, acquired and restored key examples like the Jacob Hasbrouck House (1712) and Bevier-Elting House (ca. 1709), blending revival-era renovations with efforts to maintain Dutch features such as steep roofs and gable ends. This momentum informed broader federal initiatives, including numerous listings on the National Register of Historic Places, where Dutch Colonial Revival properties underscore the style's role in safeguarding regional heritage against modernization pressures.[20] Stylistically, the Dutch Colonial Revival evolved through hybridizations that extended its adaptability, often incorporating Craftsman elements like shingled exteriors for a more rustic texture, as seen in early 20th-century examples blending Victorian Shingle influences. It also merged with Tudor Revival motifs, such as faux half-timbering on gables, creating eclectic suburban homes that balanced colonial simplicity with ornamental flair. These fusions positioned the style as a precursor to later minimalists like the Cape Cod house, which adopted simplified gabled forms and symmetrical facades from Colonial Revival variants while retaining practical, low-profile designs suited to mass production.[37][72][73] Culturally, the style embodied "authentic" American heritage, reinforcing national identity through education and media portrayals of colonial roots, much like the broader Colonial Revival's nostalgic response to industrialization and immigration. Featured in architectural periodicals and pattern books from the 1920s, it promoted ideals of stability and patriotism, influencing public perceptions of historical continuity. Economically, its accessibility via prefabricated kit homes from companies like Sears, Roebuck and Co.—which offered models like the Van Dorn with gambrel roofs—democratized the style, enabling thousands of affordable constructions between 1900 and 1940 and stimulating the burgeoning suburban housing market.[74][75]Contemporary Interpretations

Since the late 20th century, neo-revivals of Dutch Colonial Revival architecture have incorporated traditional elements like gambrel roofs into contemporary suburban designs, particularly in historicist neighborhoods of the Northeastern United States, where they blend with larger-scale homes using modern materials such as vinyl siding and simulated stone.[76] These adaptations often appear in neo-traditional developments, maximizing attic space while accommodating modern needs like integrated garages, though they sometimes draw criticism for diluting historical authenticity in oversized builds.[76] Restoration projects in the 21st century have focused on rehabilitating existing Dutch Colonial Revival structures for heritage tourism and residential use, emphasizing the preservation of iconic features like curved eaves and symmetrical facades. For instance, a 1920s Dutch Colonial Revival home in Palo Alto, California, underwent a complete interior remodel around 2018, restoring original windows and updating spaces with custom cabinetry, honed marble countertops, and open layouts to suit modern family living while maintaining the exterior's gambrel roof.[77] Another example is the renovation of a 1923 Dutch Colonial in an unspecified U.S. location, which incorporated radiant heating, Rockwool insulation for thermal and sound management, and vapor barriers to enhance habitability without altering the historic envelope.[78] Such efforts often support heritage tourism by showcasing revived examples like the Amityville Horror House, a noted Dutch Colonial Revival structure periodically restored for public interest.[76] Globally, echoes of Dutch Colonial Revival appear in Canadian architecture, with preserved and modernized examples in Vancouver featuring symmetrical two-story forms and side-gabled gambrel roofs adapted to local climates.[1] In Australia, influences from Dutch colonial traditions manifest in Revival-style homes, such as a documented example in Adelaide that retains the characteristic double-pitched roof and centered entry for contemporary occupancy.[79] Digital recreations in architecture software further propagate the style, allowing designers to model gambrel roofs and flared eaves for virtual simulations in educational and planning contexts.[80] Adapting Dutch Colonial Revival for energy efficiency presents challenges due to the style's origins in uninsulated wood-frame construction and steep roofs that complicate ventilation, but innovations like adding insulation to curved eaves and integrating solar panels into dormers have enabled sustainable updates in rehabs.[81] For example, retrofits in 1930s-era homes have addressed drafts and heat loss through modern insulation without compromising the gambrel profile, improving overall performance while meeting contemporary building codes.[81] These adaptations sustain the aesthetic in eco-conscious designs.[82] Today, Dutch Colonial Revival remains a niche presence in new U.S. home construction, comprising a small fraction of builds but enduring through neo-colonial motifs in suburban developments and active promotion by preservation societies.[83] Its visibility persists in media and design resources, where features on HGTV and similar outlets highlight restored examples to inspire heritage-inspired living.[84]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dutch_Colonial_Revival_house_in_Adelaide.jpg