Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Charging station

View on WikipediaThis article is missing information about battery-powered portable DC charging stations and other types of charging stations not used by vehicles. (August 2025) |

- Top-left: a Tesla Roadster (2008) being charged at an electric charging station in Iwata city, Japan.

- Top-right: Brammo Empulse electric motorcycle at an AeroVironment charging station and Pay as you go electric vehicle charging point.

- Bottom-left: Nissan Leaf recharging from a NRG Energy eVgo station in Houston, Texas.

- Bottom-right: converted Toyota Priuses recharging at public charging stations in San Francisco, California (2009).

A charging station, also known as a charge point, chargepoint, or electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE), is a power supply device that supplies electrical power for recharging the on-board battery packs of plug-in electric vehicles (including battery electric vehicles, electric trucks, electric buses, neighborhood electric vehicles, and plug-in hybrid vehicles).

There are two main types of EV chargers: alternating current (AC) charging stations and direct current (DC) charging stations. Electric vehicle batteries can only be charged by direct current electricity, while most mains electricity is delivered from the power grid as alternating current. For this reason, most electric vehicles have a built-in AC-to-DC converter commonly known as the "on-board charger" (OBC). At an AC charging station, AC power from the grid is supplied to this onboard charger, which converts it into DC power to recharge the battery. DC chargers provide higher-power charging (which requires much larger AC-to-DC converters) by building the converter into the charging station to avoid size, weight and cost restrictions inside vehicles. The station then directly supplies DC power to the vehicle, bypassing the onboard converter. Most modern electric vehicles can accept both AC and DC power.

Public charging stations

[edit]

Public charging stations are typically found street-side or at retail shopping centers, government facilities, and other parking areas. Private charging stations are usually found at residences, workplaces, and hotels.

Standards

[edit]Charging stations provide connectors that conform to a variety of international standards. DC charging stations are commonly equipped with multiple connectors to charge various vehicles that use competing standards.

Multiple standards have been established for charging technology to enable interoperability across vendors. Standards are available for nomenclature, power, and connectors. Tesla developed proprietary technology in these areas and began building its charging network in 2012.[1]

Nomenclature

[edit]

In 2011, the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) defined the following terms:[2]

- Socket outlet: the port on the electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE) that supplies charging power to the vehicle

- Plug: the end of the flexible cable that interfaces with the socket outlet on the EVSE. The socket outlet and plug are not used in North America because the cable is permanently attached.

- Cable: a flexible bundle of conductors that connects the EVSE with the electric vehicle

- Connector: the end of the flexible cable that interfaces with the vehicle inlet

- Vehicle inlet: the port on the electric vehicle that receives charging power

The terms "electric vehicle connector" and "electric vehicle inlet" were previously defined in the same way under Article 625 of the United States National Electrical Code (NEC) of 1999. NEC-1999 also defined the term "electric vehicle supply equipment" as the entire unit "installed specifically for the purpose of delivering energy from the premises wiring to the electric vehicle", including "conductors ... electric vehicle connectors, attachment plugs, and all other fittings, devices, power outlets, or apparatuses".[3]

Tesla, Inc. uses the term charging station as the location of a group of chargers, and the term connector for an individual EVSE.[4]

Voltage and power

[edit]Early standards

[edit]| Method | Maximum supply | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (A) | Voltage (V) | Power (kW) | |

| Level 1 (1-phase AC) | 12 | 120 | 1.44 |

| 16 | 120 | 1.92 | |

| 24 | 120 | 2.88 | |

| Level 2 (1-phase AC) | 32 | 208/240 | 7.68 |

| Level 3 (3-phase AC) | 400 | 480 | 332.6 |

The US National Electric Transportation Infrastructure Working Council (IWC) was formed in 1991 by the Electric Power Research Institute with members drawn from automotive manufacturers and the electric utilities to define standards in the US;[6] early work by the IWC led to the definition of three levels of charging in the 1999 National Electrical Code (NEC) Handbook.[5]: 9

Under the 1999 NEC, Level 1 charging equipment (as defined in the NEC handbook but not in the code) was connected to the grid through a standard NEMA 5-20R 3-prong electrical outlet with grounding, and a ground-fault circuit interrupter was required within 12 in (30 cm) of the plug. The supply circuit required protection at 125% of the maximum rated current; for example, charging equipment rated at 16 amperes ("amps" or "A") continuous current required a breaker sized to 20 A.[5]: 9

Level 2 charging equipment (as defined in the handbook) was permanently wired and fastened at a fixed location under NEC-1999. It also required grounding and ground-fault protection; in addition, it required an interlock to prevent vehicle startup during charging and a safety breakaway for the cable and connector. A 40 A breaker (125% of continuous maximum supply current) was required to protect the branch circuit.[5]: 9 For convenience and speedier charging, many early EVs preferred that owners and operators install Level 2 charging equipment, which was connected to the EV either through an inductive paddle (Magne Charge) or a conductive connector (Avcon).[5]: 10–11, 18

Level 3 charging equipment used an off-vehicle rectifier to convert the input AC power to DC, which was then supplied to the vehicle. At the time it was written, the 1999 NEC handbook anticipated that Level 3 charging equipment would require utilities to upgrade their distribution systems and transformers.[5]: 9

SAE

[edit]| Method | Maximum supply | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (A) | Voltage (V) | Power (kW) | |

| AC Level 1 | 12 | 120 | 1.44 |

| 16 | 120 | 1.92 | |

| AC Level 2 | 80 | 208–240 | 19.2 |

| DC Level 1 | 80 | 50–1000 | 80 |

| DC Level 2 | 400 | 50–1000 | 400 |

The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE International) defines the general physical, electrical, communication, and performance requirements for EV charging systems used in North America, as part of standard SAE J1772, initially developed in 2001.[8] SAE J1772 defines four levels of charging, two levels each for AC and DC supplies; the differences between levels are based upon the power distribution type, standards and maximum power.

Alternating current (AC)

[edit]AC charging stations connect the vehicle's onboard charging circuitry directly to the AC supply.[8]

- AC Level 1: Connects directly to a standard 120 V North American outlet; capable of supplying 6–16 A (0.7–1.92 kilowatts or "kW") depending on the capacity of a dedicated circuit.

- AC Level 2: Uses 240 V (single phase) or 208 V (three phase) power to supply between 6 and 80 A (1.4–19.2 kW). It provides a significant charging speed increase over AC Level 1 charging.

Direct current (DC)

[edit]Commonly, though incorrectly, called "Level 3" charging based on the older NEC-1999 definition, DC charging is categorized separately in the SAE standard. In DC fast-charging, grid AC power is passed through an AC-to-DC converter in the station before reaching the vehicle's battery, bypassing any AC-to-DC converter on board the vehicle.[8][9]

- DC Level 1: Supplies a maximum of 80 kW at 50–1000 V.

- DC Level 2: Supplies a maximum of 400 kW at 50–1000 V.

Additional standards released by SAE for charging include SAE J3068 (three-phase AC charging, using the Type 2 connector defined in IEC 62196-2) and SAE J3105 (automated connection of DC charging devices).

IEC

[edit]In 2003, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) adopted a majority of the SAE J1772 standard under IEC 62196-1 for international implementation.

| Mode | Type | Maximum supply | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current (A) | Voltage (V) | Power (kW) | ||

| 1 | 1Φ AC | 16 | 250 | 4 |

| 3Φ AC | 16 | 480 | 11 | |

| 2 | 1Φ AC | 32 | 250 | 7.4 |

| 3Φ AC | 32 | 480 | 22 | |

| 3 | 1Φ AC | 63 | 250 | 14.5 |

| 3Φ AC | 63 | 480 | 43.5 | |

| 4 | DC | 200 | 400 | 80 |

The IEC alternatively defines charging in modes (IEC 61851-1):

- Mode 1: slow charging from a regular electrical socket (single- or three-phase AC)

- Mode 2: slow charging from a regular AC socket but with some EV-specific protection arrangement (i.e. the Park & Charge or the PARVE systems)

- Mode 3: slow or fast AC charging using a specific EV multi-pin socket with control and protection functions (i.e. SAE J1772 and IEC 62196-2)

- Mode 4: DC fast charging using a specific charging interface (i.e. IEC 62196-3, such as CHAdeMO)

The connection between the electric grid and "charger" (electric vehicle supply equipment) is defined by three cases (IEC 61851-1):

- Case A: any charger connected to the mains (the mains supply cable is usually attached to the charger) usually associated with modes 1 or 2.

- Case B: an on-board vehicle charger with a mains supply cable that can be detached from both the supply and the vehicle – usually mode 3.

- Case C: DC dedicated charging station. The mains supply cable may be permanently attached to the charge station as in mode 4.

Tesla NACS

[edit]The North American Charging System (NACS) was developed by Tesla, Inc. for use in the company's vehicles. It remained a proprietary standard until 2022 when its specifications were published by Tesla.[13][14] The connector is physically smaller than the J1772/CCS connector, and uses the same pins for both AC and DC charging functionality.

As of November 2023, automakers Ford, General Motors, Rivian, Volvo, Polestar, Mercedes-Benz, Nissan, Honda, Jaguar, Fisker, Hyundai, BMW, Toyota, Subaru, and Lucid Motors have all committed to equipping their North American vehicles with NACS connectors in the future.[15][16][17] Automotive startup Aptera Motors has also adopted the connector standard in its vehicles.[18] Other automakers, such as Stellantis and Volkswagen had not made an announcement as of late 2023.[19]

To meet European Union (EU) requirements on recharging points,[20] Tesla vehicles sold in the EU are equipped with a CCS Combo 2 port. Both the North America and the EU port take 480 V DC fast charging through Tesla's network of Superchargers, which variously use NACS and CCS charging connectors. Depending on the Supercharger version, power is supplied at 72, 150, or 250 kW, the first corresponding to DC Level 1 and the second and third corresponding to DC Level 2 of SAE J1772. As of Q4 2021, Tesla reported 3,476 supercharging locations worldwide and 31,498 supercharging chargers (about 9 chargers per location on average).[4]

Development for higher power charging

[edit]An extension to the CCS DC fast-charging standard for electric cars and light trucks was being developed as of 2020, which was slated to provide higher power charging for large commercial vehicles (Class 8, and possibly 6 and 7 as well, including school and transit buses). When the Charging Interface Initiative e. V. (CharIN) task force was formed in March 2018, the new standard being developed was originally called High Power Charging (HPC) for Commercial Vehicles (HPCCV),[21] later renamed Megawatt Charging System (MCS). MCS is expected to operate in the range of 200–1500 V and 0–3000 A for a theoretical maximum power of 4.5 megawatts (MW). The proposal calls for MCS charge ports to be compatible with existing CCS and HPC chargers.[22] The task force released aggregated requirements in February 2019, which called for maximum limits of 1000 V DC (optionally, 1500 V DC) and 3000 A continuous rating.[23][needs update]

A connector design was selected in May 2019[21] and tested at the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in September 2020. Thirteen manufacturers participated in the test, which checked the coupling and thermal performance of seven vehicle inlets and eleven charger connectors.[24] The final connector requirements and specification was adopted in December 2021 as MCS connector version 3.2.[25][26]: 3 [clarification needed]

With support from Portland General Electric, on 21 April 2021 Daimler Trucks North America opened the "Electric Island", the first heavy-duty vehicle charging station, across the street from its headquarters in Portland, Oregon. The station is capable of charging eight vehicles simultaneously, and the charging bays are sized to accommodate tractor-trailers. In addition, the design is capable of accommodating >1 MW chargers once they are available.[27][clarification needed] A startup company, WattEV, announced plans in May 2021 to build a 40-stall truck stop/charging station in Bakersfield, California. At full capacity, it was slated to provide a combined 25 MW of charging power, partially drawn from an on-site solar array and battery storage.[28][needs update]

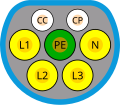

Connectors

[edit]Common connectors include Type 1 (Yazaki), Type 2 (Mennekes), CCS Combo 1 and 2, CHAdeMO, and Tesla.[29][30][31] Many standard plug types are defined in IEC 62196-2 (for AC supplied power) and 62196-3 (for DC supplied power):

- Type 1: single-phase AC vehicle coupler – SAE J1772/2009 automotive plug specifications

- Type 2: single- and three-phase AC vehicle coupler – VDE-AR-E 2623-2-2, SAE J3068, and GB/T 20234.2 plug specifications

- Type 3: single- and three-phase AC vehicle coupler equipped with safety shutters – EV Plug Alliance proposal

- Type 4: DC fast-charge couplers

| Power supply |

United States | European Union | Japan | China |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-phase AC (62196.2) |

Type 1 (SAE J1772) |

Type 2[b][c] |

Type 1 (SAE J1772) |

Type 2 (GB/T 20234.2)[d] |

| 3-phase AC (62196.2) |

Type 2 (SAE J3068) |

— | ||

| DC (62196.3) |

EE (CCS Combo 1) |

FF (CCS Combo 2)[c] |

AA (CHAdeMO)[c] |

BB (GB/T 20234.3)[b] |

ChaoJi (planned) | ||||

Quick Notes on EV Charger types

- Notes

- ^ For pin definitions, see page for each specific standard

- ^ a b In India, "low-power" vehicles with traction battery voltages less than 100 V DC use the Bharat EV Charger standards. For AC charging (230 V, 15 A / 10 kW maximum), the Bharat EV Charger AC-001 standard endorses the IEC 60309 three-pin connector. For DC charging (48–72+ V, 200 A / 15 kW maximum), the corresponding Bharat EV Charger DC-001 standard endorses the same connector used in China (GB/T 20234.3).[33]

- ^ a b c For high-power vehicles, India has largely adopted global standards: IEC 62196 Type 2 connector for AC charging (≥22 kW) and CHAdeMO and CCS Combo 2 for DC charging (≥50 kW).[32]

- ^ Although GB/T 20234.2 is physically capable of supporting three-phase power, the standard does not include its use.

CCS DC charging requires power-line communication (PLC). Two connectors are added at the bottom of Type 1 or Type 2 vehicle inlets and charging plugs to supply DC current. These are commonly known as Combo 1 or Combo 2 connectors. The choice of style inlets is normally standardized on a per-country basis so that public chargers do not need to fit cables with both variants. Generally, North America uses Combo 1 style vehicle inlets, while most of the rest of the world uses Combo 2.

The CHAdeMO standard is favored by Nissan, Mitsubishi, and Toyota, while the SAE J1772 Combo standard is backed by GM, Ford, Volkswagen, BMW, and Hyundai. Both systems charge to 80% in approximately 20 minutes, but the two systems are incompatible. Richard Martin, editorial director for clean technology marketing and consultant firm Navigant Research, stated:

The broader conflict between the CHAdeMO and SAE Combo connectors, we see that as a hindrance to the market over the next several years that needs to be worked out.[34]

Historical connectors

[edit]

In the United States, many of the EVs first marketed in the late 1990s and early 2000s such as the GM EV1, Ford Ranger EV, and Chevrolet S-10 EV preferred the use of Level 2 (single-phase AC) EVSE, as defined under NEC-1999, to maintain acceptable charging speed. These EVSEs were fitted with either an inductive connector (Magne Charge) or a conductive connector (generally AVCON). Proponents of the inductive system were GM, Nissan, and Toyota; DaimlerChrysler, Ford, and Honda backed the conductive system.[5]: 10–11

Magne Charge paddles were available in two different sizes: an older, larger paddle (used for the EV1 and S-10 EV) and a newer, smaller paddle (used for the first-generation Toyota RAV4 EV, but backwards compatible with large-paddle vehicles through an adapter).[35] The larger paddle (introduced in 1994) was required to accommodate a liquid-cooled vehicle inlet charge port; the smaller paddle (introduced in 2000) interfaced with an air-cooled inlet instead.[36][37]: 23 SAE J1773, which described the technical requirements for inductive paddle coupling, was first issued in January 1995, with another revision issued in November 1999.[37]: 26

The influential California Air Resources Board adopted the conductive connector as its standard on 28 June 2001, based on lower costs and durability,[38] and the Magne Charge paddle was discontinued by the following March.[39] Three conductive connectors existed at the time, named according to their manufacturers: Avcon (aka butt-and-pin, used by Ford, Solectria, and Honda); Yazaki (aka pin-and-sleeve, on the RAV4 EV); and ODU (used by DaimlerChrysler).[37]: 22 The Avcon butt-and-pin connector supported Level 2 and Level 3 (DC) charging and was described in the appendix of the first version (1996) of the SAE J1772 recommended practice; the 2001 version moved the connector description into the body of the practice, making it the de facto standard for the United States.[37]: 25 [40] IWC recommended the Avcon butt connector for North America,[37]: 22 based on environmental and durability testing.[41] As implemented, the Avcon connector used four contacts for Level 2 (L1, L2, Pilot, Ground) and added five more (three for serial communications, and two for DC power) for Level 3 (L1, L2, Pilot, Com1, Com2, Ground, Clean Data ground, DC+, DC−).[42] By 2009, J1772 had instead adopted the round pin-and-sleeve (Yazaki) connector as its standard implementation, and the rectangular Avcon butt connector was rendered obsolete.[43]

Charging time

[edit]-

BYD e6. Able to recharge the battery in 15 minutes to 80%

-

Solaris Urbino 12 electric, battery electric bus, inductive charging station

Charging time depends on the battery's capacity, power density, and charging power.[44] The larger the capacity, the more charge the battery can hold (analogous to the size of a fuel tank). Higher power density allows the battery to accept more charge per unit time (the size of the tank opening). Higher charging power supplies more energy per unit time (analogous to a pump's flow rate). An important downside of charging at fast speeds is that it also adds stress to the mains electricity grid.[45]

The California Air Resources Board specified a target minimum range of 150 miles (240 km) to qualify as a zero-emission vehicle, and further specified that the vehicle should allow for fast-charging.[46]

Charge time can be calculated as:[47]

The effective charging power can be lower than the maximum charging power due to limitations of the battery or battery management system, charging losses (which can be as high as 25%[48]), and vary over time due to charging limits applied by a charge controller.

In early 2025, two Chinese companies announced battery technology to enable electric vehicles to drive long distances on a five-minute charge.[49] BYD developed a battery with a peak charging capacity of 1,000 kW (1 MW), compared to US chargers then having peak rates of 400 kW or less.[49] China's grid infrastructure allows high-power charging hubs to be connected directly to the power grid—sometimes even to high-voltage lines—avoiding the delay of local utility upgrades in the US.[49]

Battery capacity

[edit]The usable battery capacity of a first-generation electric vehicle, such as the original Nissan Leaf, was about 20 kilowatt-hours (kWh), giving it a range of about 100 mi (160 km).[citation needed] Tesla was the first company to introduce longer-range vehicles, initially releasing their Model S with battery capacities of 40 kWh, 60 kWh and 85 kWh, with the latter lasting for about 480 km (300 mi).[50] As of 2022[update] plug-in hybrid vehicles typically had an electric range of 15 to 60 miles (24–97 km).[51]

AC-to-DC conversion

[edit]Batteries are charged with DC power. To charge from the AC power supplied by the electrical grid, EVs have a small AC-to-DC converter built into the vehicle. The charging cable supplies AC power directly from the grid, and the vehicle converts this power to DC internally and charges its battery. The built-in converters on most EVs typically support charging speeds up to 6–7 kW, sufficient for overnight charging.[52] This is known as "AC charging". To facilitate rapid recharging of EVs, much higher power (50–100+ kW) is necessary.[citation needed] This requires a much larger AC-to-DC converter which is not practical to integrate into the vehicle. Instead, the AC-to-DC conversion is performed by the charging station, and DC power is supplied to the vehicle directly, bypassing the built-in converter. This is known as DC fast charging.

| Configuration | Voltage | Current | Power | Charging time | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-phase AC | 120 V | 12 A | 1.44 kW | 13 hours | This is the maximum continuous power available from a standard US/Canadian 120 V 15 A circuit |

| Single-phase AC | 230 V | 16 A | 3.68 kW | 5.1 hours | This is the maximum continuous power available from a CEE 7/3 ("Schuko") receptacle on a 16 A rated circuit |

| Single-phase AC | 240 V | 30 A | 7.20 kW | 2.6 hours | Common maximum limit of public AC charging stations used in North America, such as a ChargePoint CT4000 |

| Three-phase AC | 400 V | 16 A | 11.0 kW | 1.7 hours | Maximum limit of a European 16 A three-phase AC charging station |

| Three-phase AC | 400 V | 32 A | 22.1 kW | 51 minutes | Maximum limit of a European 32 A three-phase AC charging station |

| DC | 400 V | 125 A | 50 kW | 22 minutes | Typical mid-power DC charging station |

| DC | 400 V | 300 A | 120 kW | 9 minutes | Typical power from a Tesla V2 Tesla Supercharger |

Safety

[edit]-

A Sunwin electric bus in Shanghai at a charging station

-

A battery electric bus charging station in Geneva, Switzerland

Charging stations are usually accessible to multiple electric vehicles and are equipped with current or connection sensing mechanisms to disconnect the power when the EV is not charging.

The two main types of safety sensors:

- Current sensors monitor power consumed, and maintain the connection only while demand is within a predetermined range.[citation needed]

- Sensor wires provide a feedback signal such as specified by the SAE J1772 and IEC 62196 schemes that require special (multi-pin) power plug fittings.

Sensor wires react more quickly, have fewer parts to fail, and are possibly less expensive to design and implement.[citation needed] Current sensors however can use standard connectors and can allow suppliers to monitor or charge for the electricity actually consumed.

Public charging stations over the world

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (February 2023) |

Longer drives require a network of public charging stations. In addition, they are essential for vehicles that lack access to a home charging station, as is common in multi-family housing. Costs vary greatly by country, power supplier, and power source. Some services charge by the minute, while others charge by the amount of energy received (measured in kilowatt-hours). In the United States, some states have banned the use of charging by kWh.[54]

Charging stations may not need much new infrastructure in developed countries, less than delivering a new fuel over a new network.[55] The stations can leverage the existing ubiquitous electrical grid.[56]

Charging stations are offered by public authorities, commercial enterprises, and some major employers to address a range of barriers. Options include simple charging posts for roadside use, charging cabinets for covered parking places, and fully automated charging stations integrated with power distribution equipment.[57]

As of December 2012[update], around 50,000 non-residential charging points were deployed in the US, Europe, Japan and China.[58] As of August 2014[update], some 3,869 CHAdeMO quick chargers were deployed, with 1,978 in Japan, 1,181 in Europe and 686 in the United States, and 24 in other countries.[59] As of December 2021 the total number of public and private EV charging stations was over 57,000 in the United States and Canada combined.[60] As of May 2023, there are over 3.9 million public EV charging points worldwide, with Europe having over 600,000, China leading with over 2.7 million.[61] United States has over 138,100 charging outlets for plug-in electric vehicles (EVs). In January 2023, S&P Global Mobility estimated that the US has about 126,500 Level 2 and 20,431 Level 3 charging stations, plus another 16,822 Tesla Superchargers and Tesla destination chargers.[62]

Asia/Pacific

[edit]In 2012, there are 17,000 public charging stations in China, mostly built by State Grid as a pilot program in major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Shenzhen and Hefei. As of July 2024[update], China's total number of charging stations have reached 10.6 million, which include 3.2 million public units and 7.4 million private units, with over 55% being DC charging stations according to CCTV News,[63] making China the country with the largest and most diverse vehicle charging network in the world.[64]

As of December 2012[update], Japan had 1,381 public DC fast-charging stations, the largest deployment of fast chargers in the world, but only around 300 AC chargers.[58]

As of September 2013[update], the largest public charging networks in Australia were in the capital cities of Perth and Melbourne, with around 30 stations (7 kW AC) established in both cities – smaller networks exist in other capital cities.[65]

In India, public electric vehicle (EV) charging stations are commonly located street-side and at retail shopping centers, government facilities, and other parking areas. Private charging stations are typically found at residences, workplaces, and hotels.[citation needed]

-

Charging park in Beijing (2016)

-

EV charging station, Seogwipo, Jeju Island, South Korea (2021)

-

Prototype modified Renault Laguna EVs charging at Project Better Place charging stations in Ramat Hasharon, Israel, north of Tel Aviv (2010)

Europe

[edit]As of December 2013, Estonia was the only country that had completed the deployment of an EV charging network with nationwide coverage, with 165 fast chargers available along highways at a maximum distance of between 40–60 km (25–37 mi), and a higher density in urban areas.[66][67][68]

-

Swedish charging station with 400 kW fast chargers (2024)

-

Public charging park in Germany (2020)

-

Electric-vehicle charging station near London (2023)

-

eVolt Tri-Rapid Compact Charger (left) and eVolt Standard Post charger with Type 1 and Type 2 ports in a car park in Arbroath, Scotland (2017)

-

Car charging point in Moscow (2024)

-

Aral Pulse charging stations in front of a Aral-branded BP gas station in Braunschweig, Germany (2021)

As of November 2012, about 15,000 charging stations had been installed in Europe.[69] As of March 2013, Norway had 4,029 charging points and 127 DC fast-charging stations.[70] As part of its commitment to environmental sustainability, the Dutch government initiated a plan to establish over 200 fast (DC) charging stations across the country by 2015. The rollout will be undertaken by ABB and Dutch startup Fastned, aiming to provide at least one station every 50 km (31 mi) for the Netherlands' 16 million residents.[71] In addition to that, the E-laad foundation installed about 3000 public (slow) charge points since 2009.[72]

Compared to other markets, such as China, the European electric car market has developed slowly. This, together with the lack of charging stations, has reduced the number of electric models available in Europe.[73] In 2018 and 2019 the European Investment Bank (EIB) signed several projects with companies like Allego, Greenway, BeCharge and Enel X. The EIB loans will support the deployment of the charging station infrastructure with a total of €200 million.[73] The UK government declared that it will ban the selling of new petrol and diesel vehicles by 2035 for a complete shift towards electric charging vehicles.[74]

North America

[edit]As of February 2025, there are 84,191 charging stations, including the Level 1, Level 2 and DC fast-charging stations, across the United States and Canada.[75]

As of October 2023, in the US and Canada, there are 6,502 stations with CHAdeMO connectors, 7,480 stations with SAE CCS1 connectors, and 7,171 stations with Tesla North American Charging System (NACS) connectors, according to the US Department of Energy's Alternative Fuels Data Center.[75]

As of August 2018[update], 800,000 electric vehicles and 18,000 charging stations operated in the United States,[76] up from 5,678 public charging stations and 16,256 public charging points in 2013.[77][78] By July 2020, Tesla had installed 1,971 stations (17,467 plugs).[79]

Colder areas in northern US states and Canada have some infrastructure for public power receptacles provided primarily for use by block heaters. Although their circuit breakers prevent large current draws for other uses, they can be used to recharge electric vehicles, albeit slowly.[80] In public lots, some such outlets are turned on only when the temperature falls below −20 °C, further limiting their value.[81]

As of late 2023, a limited number of Tesla Superchargers are starting to open to non-Tesla vehicles through the use of a built in CCS adapter for existing superchargers.[82]

Other charging networks are available for all electric vehicles. Networks like Electrify America, EVgo, ChargeFinder and ChargePoint are popular among consumers. Electrify America currently has 15 agreements with various automakers for their electric vehicles to use its network of chargers or provide discounted charging rates or complimentary charging, including Audi, BMW, Ford, Hyundai, Kia, Lucid Motors, Mercedes, Volkswagen, and more. Prices are generally based on local rates and other networks may accept cash or a credit card.

In June 2022, United States President Biden announced a plan for a standardized nationwide network of 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations by 2030 that will be agnostic to EV brands, charging companies, or location, in the United States.[83] The US will provide US$5 billion between 2022 and 2026 to states through the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program to build charging stations along major highways and corridors.[84] One such proposed corridor called Greenlane plans to establish charging infrastructure between Los Angeles, California and Las Vegas, Nevada.[85] However, by December 2023, no charging stations had been built.[86]

Africa

[edit]

South Africa

[edit]South Africa has a small, but expanding network of charging stations, and a growing number of EVs and PHEVs on the road. There is no direct government infrastructure spending on EV charging, and SA therefore has a patchwork of private charging sites. Investment in infrastructure is increasing.

There are already proof of concept high-capacity DC chargers installed at various sites across SA, including the three 400 kW chargers at Zero Carbon Charge's N12 North West facility, the 200 kW station at the Mall of Africa in Midrand, and the 150 kW one at Canal Walk in Cape Town.

The cost of installing a charging station is estimated to be between R500,0000 and R2 million. To reach profitability, SA will need around 100,000 EVs on the road.[87]

As of 2025, there are around 3,500 new EVs sold per year in South Africa. Sales are expected to grow steadily, as new models are introduced into the market. At the same time, the industry was estimated to already be worth R2.8 billion.[87]

There are plans to build around xxxxxx charging stations over the next few years. Companies included in these developments are Eskom, BYD,[88] the National Automobile Association of South Africa[88], and Cape Town-based Zero Carbon Charge, with its solar-powered passenger vehicle and electric truck charging stations, as part of a R100 million investment from the Development Bank of Southern Africa).[89][90][91]

South America

[edit]In April 2017 YPF, the state-owned oil company of Argentina, reported that it will install 220 fast-load stations for electric vehicles in 110 of its service stations in the national territory.[92]

Projects

[edit]Electric car manufacturers, charging infrastructure providers, and regional governments have entered into agreements and ventures to promote and provide electric vehicle networks of public charging stations.

The EV Plug Alliance[93] is an association of 21 European manufacturers that proposed an IEC norm and a European standard for sockets and plugs. Members (Schneider Electric, Legrand, Scame, Nexans, etc.) claimed that the system was safer because they use shutters. Prior consensus was that the IEC 62196 and IEC 61851-1 standards have already established safety by making parts non-live when touchable.[94][95][96]

Home chargers

[edit]

Over 80% of electric vehicle charging is done at home, usually in a garage.[97] In North America, Level 1 charging is connected to a standard 120 volt outlet and provides less than 5 miles (8.0 km) of range per hour of charging.

To address the need for faster charging, Level 2 charging stations have become more prevalent. These stations operate at 240 volts and can significantly increase the charging speed, delivering up to more than 30 miles (48 km) of range per hour. Level 2 chargers offer a more practical solution for EV owners, especially for those who have higher daily mileage requirements.

Charging stations can be installed using two main methods: hardwired connections to the main electrical panel box or through a cord and plug connected to a 240-volt receptacle. A popular choice for the latter is the NEMA 14-50 receptacle. This type of outlet provides 240 volts and, when wired to a 50-ampere circuit, can support charging at 40 amperes according to North American electrical code. This translates to a power supply of up to 9.6 kilowatts,[98] offering a faster and more efficient charging experience.

Battery swap

[edit]A battery swapping (or switching) station allow vehicles to exchange a discharged battery pack for a charged one, eliminating the charge interval. Battery swapping is common in electric forklift applications.[99]

History

[edit]The concept of an exchangeable battery service was proposed as early as 1896. It was first offered between 1910 and 1924, by Hartford Electric Light Company, through the GeVeCo battery service, serving electric trucks. The vehicle owner purchased the vehicle, without a battery, from General Vehicle Company (GeVeCo), part-owned by General Electric.[100] The power was purchased from Hartford Electric in the form of an exchangeable battery. Both vehicles and batteries were designed to facilitate a fast exchange. The owner paid a variable per-mile charge and a monthly service fee to cover truck maintenance and storage. These vehicles covered more than 6 million miles (9.7 million kilometres).

Beginning in 1917, a similar service operated in Chicago for owners of Milburn Electric cars.[101] 91 years later, a rapid battery replacement system was implemented to service 50 electric buses at the 2008 Summer Olympics.[102]

Better Place, Tesla, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries considered battery switch approaches.[103][104] One complicating factor was that the approach requires vehicle design modifications.

In 2012, Tesla started building a proprietary fast-charging Tesla Supercharger network.[1] In 2013, Tesla announced it would also support battery pack swaps.[105] A demonstration swapping station was built at Harris Ranch and operated for a short period of time. However customers vastly preferred using the Superchargers, so the swapping program was shut down.[106]

Benefits

[edit]The following benefits were claimed for battery swapping:

- "Refueling" in under five minutes.[107][108]

- Automation: The driver can stay in the car while the battery is swapped.[109]

- Switch company subsidies could reduce prices without involving vehicle owners.[110]

- Spare batteries could participate in vehicle-to-grid energy services.[111]

Providers

[edit]

The Better Place network was the first modern attempt at the battery switching model. The Renault Fluence Z.E. was the first car enabled to adopt the approach and was offered in Israel and Denmark.[112]

Better Place launched its first battery-swapping station in Israel, in Kiryat Ekron, near Rehovot in March 2011. The exchange process took five minutes.[107][113] Better Place filed for bankruptcy in Israel in May 2013.[114][115]

In June 2013, Tesla announced its plan to offer battery swapping. Tesla showed that a battery swap with the Model S took just over 90 seconds.[108][116] Elon Musk said the service would be offered at around US$60 to US$80 at June 2013 prices. The vehicle purchase included one battery pack. After a swap, the owner could later return and receive their battery pack fully charged. A second option would be to keep the swapped battery and receive/pay the difference in value between the original and the replacement. Pricing was not announced.[108] In 2015 the company abandoned the idea for lack of customer interest.[117]

By 2022, Chinese luxury carmaker Nio had built more than 900 battery swap stations across China and Europe,[118] up from 131 in 2020.[119]

Sites

[edit]

Unlike filling stations, which need to be located near roads that tank trucks can enter conveniently, charging stations can theoretically be placed anywhere with access to electric power and adequate parking.

Private locations include residences, workplaces, and hotels.[120] Residences are by far the most common charging location.[121] Residential charging stations typically lack user authentication and separate metering, and may require a dedicated circuit.[122] Many vehicles being charged at residences simply use a cable that plugs into a standard household electrical outlet.[123] These cables may be wall mounted.[citation needed]

Public stations have been sited along highways, in shopping centers, hotels, government facilities and at workplaces. Some gas stations offer EV charging stations.[124] Some charging stations have been criticized as inaccessible, hard to find, out of order, and slow, thus slowing EV adoption.[125]

Public charge stations may charge a fee or offer free service based on government or corporate promotions. Charge rates vary from residential rates for electricity to many times higher. The premium is usually for the convenience of faster charging. Vehicles can typically be charged without the owner present, allowing the owner to partake in other activities.[126] Sites include malls, freeway rest areas, transit stations, and government offices.[127][128] Typically, AC Type 1/Type 2 plugs are used.

Wireless charging uses inductive charging mats that charge without a wired connection and can be embedded in parking stalls or even on roadways.

Mobile charging involves another vehicle that brings the charge station to the electric vehicle; the power is supplied via a fuel generator (typically gasoline or diesel), or a large battery.

An offshore electricity recharging system named Stillstrom, to be launched by Danish shipping firm Maersk Supply Service, will give ships access to renewable energy while at sea.[129] Connecting ships to electricity generated by offshore wind farms, Stillstrom is designed to cut emissions from idling ships.[129]

Related technologies

[edit]Smart grid

[edit]A smart grid is a power grid that can adapt to changing conditions by limiting service or adjusting prices. Some charging stations can communicate with the grid and activate charging when conditions are optimal, such as when prices are relatively low. Some vehicles allow the operator to control recharging.[130] Vehicle-to-grid scenarios allow the vehicle battery to supply the grid during periods of peak demand. This requires communication between the grid, charging station, and vehicle. SAE International is developing related standards. These include SAE J2847/1.[131][132] ISO and IEC are developing similar standards known as ISO/IEC 15118, which also provide protocols for automatic payment.

Renewable energy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2023) |

Electric vehicles (EVs) can be powered by renewable energy sources like wind, solar, hydropower, geothermal, biogas, and some low-impact hydroelectric sources. Renewable energy sources are generally less expensive, cleaner, and more sustainable than non-renewable sources like coal, natural gas, and petroleum power.[133]

Charging stations are powered by whatever the power grid runs on, which might include oil, coal, and natural gas. However, many companies have been making advancements towards clean energy for their charging stations. As of November 2023, Electrify America has invested over $5 million to develop over 50 solar-powered electric vehicle (EV) charging stations in rural California, including areas like Fresno County. These resilient Level 2 (L2) stations aren't tied to the electrical grid, and they provide drivers in rural areas access to EV charging via renewable resources. Electrify America’s Solar Glow 1 project, a 75-megawatt solar power initiative in San Bernardino County, is expected to generate 225,000 megawatt-hours of clean electricity annually, enough to power over 20,000 homes.[134][135]

Tesla's Superchargers and Destination Chargers are mostly powered by solar energy. Tesla's Superchargers have solar canopies with solar panels that generate energy to offset electricity use. Some Destination Chargers have solar panels mounted on canopies or nearby rooftops to generate energy. As of 2023, Tesla's global network was 100% renewable, achieved through a combination of onsite resources and annual renewable matching.

The E-Move Charging Station is equipped with eight monocrystalline solar panels, which can supply 1.76 kW of solar power.[136]

In 2012, Urban Green Energy introduced the world's first wind-powered electric vehicle charging station, the Sanya SkyPump. The design features a 4 kW vertical-axis wind turbine paired with a GE WattStation.[137]

In 2021, Nova Innovation introduced the world's first direct from tidal power EV charge station.[138]

Alternative technologies

[edit]Along a section of the Highway E20 in Sweden, which connects Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö, a plate has been placed under the asphalt that interfaces with electric cars, recharging an electromagnetic coil receiver.

This allows greater vehicle autonomy and reduces the size of the battery compartment. The technology is planned to be implemented along 3,000 km of Swedish roads.[139] Sweden's first electrified stretch of road, and the world's first permanent one,[140] connects the Hallsberg and Örebro area. The work is scheduled for completion by 2025.[141]

See also

[edit]- AC adapter

- Automated charging machine

- Battery charger

- Direct coupling

- Electric vehicle battery

- Electric vehicle network

- Inductive charging

- Ground-level power supply

- ISO 15118

- List of energy storage projects

- Megawatt Charging System

- OpenEVSE

- Park & Charge

- Solar vehicle

- Vehicle-to-grid

Commercial projects:

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Tesla Motors Launches Revolutionary Supercharger Enabling Convenient Long Distance Driving | Tesla Investor Relations". ir.tesla.com. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2022.[self-published source]

- ^ "ACEA position and recommendations for the standardization of the charging of electrically chargeable vehicles" (PDF). ACEA – European Automobile Manufacturers Association. 2 March 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2012.

- ^ "NEC 1999 Article 625 – Electric Vehicle Charging System". National Electrical Code. 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b "TSLA Q4 Update" (PDF). tesla-cdn.thron.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Electric Vehicle Charging Equipment Installation Guide" (PDF). State of Massachusetts, Division of Energy Resources. January 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2000.

- ^ "Infrastructure Working Council". Electric Power Research Institute. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "SAE Electric Vehicle and Plug in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Conductive Charge Coupler". SAE International. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "What's the Difference Between EV Charging Levels?". FreeWire Technologies. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "What is Fast Charging". chademo.com. CHAdeMO Association. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "IEC 61851-1: 2017 Electrical vehicle conductive charging system, Part 1: General requirements". International Electrotechnical commission. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Charging modes (IEC-61851-1)". Circutor. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Ferrari, Lorenzo (20 December 2019). "Charging modes for electric vehicles". Daze Technology. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Opening the North American Charging Standard". tesla.com. 11 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Valdes-Dapena, Peter (11 November 2022). "Tesla officially makes its charging standard available to other companies". CNN. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Ford, Toyota, Hyundai, and more – here's the full list of car companies adopting Tesla's charging technology". Business Insider. 20 October 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Roth, Emma (1 November 2023). "Subaru is adopting Tesla's EV charging port as holdout numbers dwindle". The Verge. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Doll, Scooter (6 November 2023). "Lucid Motors joins the 'in crowd,' will adopt NACS and offer access to Tesla's Supercharger network". Electrek. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Is Aptera Using Tesla's Charging Tech: 1,000-Mile, Supercharge-Capable EV?". InsideEVs. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ St. John, Alexa; Rapier, Graham. "Only 2 major car companies haven't joined Tesla's charging tech yet". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Directive 2014/94/EU on the deployment of alternative fuels". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b "CharIN HPCCV Task Force: High Power Plug Update [PDF]". CharIN. April 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "CharIN Develops Super Powerful Charger With Over 2 MW Of Power". insideevs.com.

- ^ CharIN High Power Commercial Vehicle Charging Task Force Aggregated Requirements (PDF) (Report). CharIN. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2019.

- ^ "The CharIN path to Megawatt Charging (MCS): Successful connector test event at NREL" (Press release). CharIN. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Gehm, Ryan (27 May 2021). "Mega push for heavy-duty EV charging". Truck & Off-Highway Engineering. Society of Automotive Engineers. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Bohn, Theodore (12 April 2022). "SAE J3271 Megawatt Charging System standard; part of MW+ multiport electric vehicle charging for everything that 'rolls, flies or floats'". EPRI Bus & Truck. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Daimler Trucks North America, Portland General Electric open first-of-its-kind heavy-duty electric truck charging site" (Press release). Daimler Trucks North America. 21 April 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Edelstein, Stephen (16 May 2021). "This electric truck stop won't offer gas or diesel—just 25 MW of solar-supplemented charging". Green Car Reports. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Hosseini, Seyed Hossein (May 2020). "An Extendable Quadratic Bidirectional DC–DC Converter for V2G and G2V Applications". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 68 (6): 4859–4869. doi:10.1109/TIE.2020.2992967. hdl:10197/12654. ISSN 1557-9948. S2CID 219501762.

- ^ "A Simple Guide to DC Fast Charging". fleetcarma.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Ireland, Electric Car Charger (15 February 2023). "EV Charging Connector Types Demystified". Electric Car Chargers Ireland. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "The Future of Bharat Charging Standard DC-001". EV Reporter. 9 October 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Committee Report on Standardization of Public EV Chargers" (PDF). Government of India, Ministry of Heavy Industries. 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Pyper, Juliet (24 July 2013). "Charger standards fight confuses electric vehicle buyers, puts car company investments at risk". ClimateWire. E&E Publishing. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "News Archive 1". Magne Charge. December 2000. Archived from the original on 2 March 2001.

- ^ "News Archive 2". Magne Charge. December 2000. Archived from the original on 2 March 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Staff Report: Initial Statements of Reasons (PDF) (Report). California Air Resources Board. 11 May 2001. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "ARB Amends ZEV Rule: Standardizes Chargers & Addresses Automaker Mergers" (Press release). California Air Resources Board. 28 June 2001. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "GM Pulls the Plug on Inductive Charging". GM Advanced Technology Vehicles – Torrance Operations. 15 March 2002. Archived from the original on 28 January 2004.

- ^ "SAE J1772 Overview based on the OLD 2001 version of SAE J1772". Modular EV Power. 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "SAE Committee Selects Conductive Technology for Use As a Universal Electric Vehicle Charging Standard" (Press release). Society of Automotive Engineers, Electric Vehicle Charging Systems Committee. 27 May 1998. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Component Products". Avcon. 28 June 2001. Archived from the original on 13 August 2001.

- ^ "SAE J1772 Compliant Electric Vehicle Connector". Electric Vehicles News. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Spendiff-Smith, Matthew (18 May 2023). "The Comprehensive Guide to Level 2 EV Charging – EVESCO". Power Sonic. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Who killed the electric grid? Fast-charging electric cars". lowtechmagazine.com. 10 March 2009.

- ^ "California moves to accelerate to 100% new zero-emission vehicle sales by 2035 California Air Resources Board". ww2.arb.ca.gov. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Guide to buy the right EV home charging station". US: Home Charging Stations. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ "Bordcomputer: Wie genau ist die Verbrauchsanzeige?". adac.de (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Brown, Claire (19 August 2025). "Why Can't the U.S. Build 5-Minute E.V. Chargers?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 August 2025.

- ^ Movement, Q. ai-Powering a Personal Wealth. "Tesla: A History Of Innovation (and Headaches)". Forbes. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles". Alternative Fuels Data Center. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "EV charging: the difference between AC and DC | EVBox". blog.evbox.com. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Fuel Efficiency for 2020 Tesla Model S Long Range". US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Benoit, Charles (12 August 2019). "30 states allow kWh pricing, but non-Tesla EV drivers mostly miss benefits". Electrek.

- ^ "Plug-In 2008: Company News: GM/ V2Green/ Coulomb/ Google/ HEVT/ PlugInSupply". CalCars. 28 July 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "From Home to Work, the Average Commute is 26.4 Minutes" (PDF). OmniStats. 3 (4). October 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

Source: US Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Omnibus Household Survey. Data from the February, April, June, and August 2003 surveys have been combined. Data cover activities for the month prior to the survey.

- ^ "Electric vehicles – About electric vehicles – Charging – suppliers". london.gov.uk. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ^ a b International Energy Agency; Clean Energy Ministerial; Electric Vehicles Initiative (April 2013). "Global EV Outlook 2013 – Understanding the Electric Vehicle Landscape to 2020" (PDF). International Energy Agency. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ "CHAdeMO Association". Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Electric Vehicle (EV) Industry Statistics and Forecasts". EVhype. August 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "EVO Report 2024 | BloombergNEF | Bloomberg Finance LP". BloombergNEF. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "EV Chargers: How many do we need?". News Release Archive. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "全国充电桩数量已达1060.4万台 其中大功率充电桩增幅明显". 央视新闻. 19 August 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ "专家解读:2024年7月全国充电桩市场分析". 搜狐网. 19 August 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ Bräunl, Thomas (16 September 2013). "Setting the standard: Australia must choose an electric car charging norm". The Conversation Australia. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Palin, Adam (19 November 2013). "Infrastructure: Shortage of electric points puts the brake on sales". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ KredEx (20 February 2013). "Estonia becomes the first in the world to open a nationwide electric vehicle fast-charging network". Estonian World. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Vaughan, Adam (20 February 2013). "Estonia launches national electric car charging network". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Renault (17 December 2012). "Renault delivers first ZOE EV" (Press release). Green Car Congress. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Ladepunkter i Norge" [Charge Points in Norway] (in Norwegian). Grønn bil. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ Toor, Amar (10 July 2013). "Every Dutch citizen will live within 31 miles of an electric vehicle charging station by 2015". The Verge. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Ondersteuning laadinfrastructuur elektrische auto's wordt voortgezet". e-laad.nl (in Dutch). 21 January 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ a b "The future of e-mobility is now". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Petrol and diesel car sales ban brought forward to 2035". BBC. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Electric Vehicle Charging Station Locations". Alternative Fuels Data Center. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Utilities, states work together to expand EV charging infrastructure". Daily Energy Insider. 13 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Alternative Fueling Station Counts by State". Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC). United States Department of Energy. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013. The AFDC counts electric charging units or points, or EVSE, as one for each outlet available, and does not include residential electric charging infrastructure.

- ^ King, Danny (10 April 2013). "US public charging stations increase by 9% in first quarter". Autoblog Green. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "Supercharger". Tesla. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Electric Vehicles, Manitoba Hydro, retrieved 2 April 2013,

Manitobans' experience with cold weather and plugging in their vehicles will help ease the transition to adopting PEVs. In some circumstances, the existing infrastructure used to power vehicle block heaters in the winter can also be used to provide limited charging for PEVs. However, some existing electrical outlets may not be suitable for PEV charging. Residential outlets can be part of a circuit used to power multiple lights and other electrical devices, and could become overloaded if used to charge a PEV. A dedicated circuit for PEV charging may need to be installed by a licensed electrician in these situations. Also, some commercial parking lot outlets operate in a load restricted or cycled manner and using them may result in your PEV receiving a lower charge than expected or no charge at all. If a parking stall is not specifically designated for PEV use, we recommend that you consult with the parking lot or building manager to ensure it can provide adequate power to your vehicle.

- ^ "Park and Ride Locations". Calgary Transit. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 19 September 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

The plug-ins located in the Park and Ride lots automatically turn on when the outside temperature falls below −20 degrees and turn off and on in increments to save electricity usage.

- ^ "Supercharging". tesla.com. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Newburger, Emma (9 June 2022). "Biden announces standards to make electric vehicle charging stations accessible". CNBC. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Bipartisan Infrastructure Law – National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program Fact Sheet". Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Greenlane Announces 280-mile Corridor of Commercial EV Charging Stations from Los Angeles to Las Vegas" (Press release). Daimler Truck North America. 27 March 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Bikales, James (5 December 2023). "Congress provided $7.5B for electric vehicle chargers. Built so far: Zero". Politico.

- ^ a b Yunus Kemp (4 June 2025). "South Africa: 100,000 EVs needed for charging sector to make bank". ESI Africa. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ a b Hanno Labuschagne (5 October 2025). "Important information for electric car owners in South Africa". MyBroadband. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ "Zero Carbon Charge - Homepage". Zero Carbon Charge. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ Terence Creamer (26 May 2025). "DBSA invests R100m into EV charging station company". Engineering News. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ Hanno Labuschagne (29 July 2025). "The former Naspers man and the farmer building South Africa's first Eskom-free electric car charging network". MyBroadband. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ "Repsol back on track on YPF road: now for electric cars". ambito.com (in Spanish). 24 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "EVPlug Alliance". Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "MENNEKES – Plugs for the world: The solution for Europe: type 2 charging sockets with or without shutter". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ IEC 62196-1.

- ^ IEC 61851-1.

- ^ "Guide on charging your electric vehicle at home". ChargeHub. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Types of Electrical Outlets for Electric Car Chargers". NeoCharge.

- ^ "Industrial electrical vehicle stalwarts head out on the road". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Cassidy, William B. (30 September 2013). "Trucking's Eclipsed Electric Age". The Lost Annals of Transport. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Kirsch, David A. (2000). The Electric Vehicle and the Burden of History. Rutgers University Press. pp. 153–162. ISBN 0-8135-2809-7.

- ^ "BIT Attends the Delivery Ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games – Alternative Fuel Vehicles". Beijing Institute of Technology. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Blanco, Sebastian (27 September 2009). "REPORT: Tesla Model S was designed with battery swaps in mind". Autoblog Green. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Mitsubishi working on battery swapping for transit buses, Better Place not involved".

- ^ Green, Catherine (21 June 2013). "Tesla shows off its battery-swapping station: 90 seconds and less than $100". Silicon Valley Mercury News. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Tesla shuts down battery swap program in favor of Superchargers, for now". teslarati.com. 6 November 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ a b Udasin, Sharon (24 March 2011). "Better Place launches 1st Israeli battery-switching station". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogowsky, Mark (21 June 2013). "Tesla 90-Second Battery Swap Tech Coming This Year". Forbes. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Better Place, battery switch station description". Archived from the original on 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Better Place's Renault Fluence EV to sell for under $20,000".

- ^ mnlasia (10 July 2022). "What is Vehicle-to-grid technology | MNL Asia". Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Better Place. The Renault Fluence ZE". Better Place. 22 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Motavalli, Jim (29 July 2011). "Plug-and-Play Batteries: Trying Out a Quick-Swap Station for E.V.'s". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (26 May 2013). "Israeli Venture Meant to Serve Electric Cars Is Ending Its Run". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Elis, Niv (26 May 2013). "Death of Better Place: Electric car co. to dissolve". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Tesla Motors demonstrates battery swap in the Model S". Green Car Congress. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Sorokanich, Robert (10 June 2015). "Musk: Tesla "unlikely" to pursue battery swapping stations". Road & Track. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Could battery swapping replace EV charging?". Autocar. 4 April 2022. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Hanley, Steve (31 May 2020). "NIO Completes More Than 500,000 Battery Swaps". CleanTechnica.

- ^ "Site Hosts for EV Charging Stations". US Department of Transportation. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Charging at Home". Energy.gov. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Stenquist, Paul (11 July 2019). "Electric Chargers for the Home Garage". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "2021 U.S. Electric Vehicle Experience (EVX) Home Charging Study". J.D. Power. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Peters, Adele (8 October 2018). "Want electric vehicles to scale? Add chargers to gas stations". Fast Company. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (22 July 2017). "Tesla Superchargers vs … Ugh". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

needs to be done to make a charging network or just individual charging stations adequate for EV drivers ... plenty of complaints about such inaccessible charging stations ... it can take what seems like ages to actually find the station because of how invisible it is ... some charging stations are down 50% of the time ... Unless you're willing to increase your travel time by ≈50%, charging at 50 kW on a road trip doesn't really cut it ...

- ^ Savard, Jim (16 August 2018). "Is it Time to Add Electric Vehicle Charging Stations to Your Retail Shopping Center?". Metro Commercial. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Workplace Charging for Plug-In Electric Vehicles". Alternative Fuels Data Center. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Siddiqui, Faiz (14 September 2015). "There are now more places to charge your electric vehicle in Maryland – for free". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b Wallace, Abby (20 February 2022). "These floating charging points will let ships draw electricity from offshore wind farms – and could recharge battery-powered vessels of the future". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Tesla Motors Introduces Mobile App for Model S Sedan". 6 February 2013.

- ^ "SAE Ground Vehicle Standards Status of work – PHEV +" (PDF). SAE International. January 2010. pp. 1–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "J2931/1B (WIP) Digital Communications for Plug-in Electric Vehicles – SAE International". sae.org. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Where Do Electric Car Charging Stations Get Their Power From". Energy5. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (16 February 2023). "Solar-Powered EV Charging from Electrify America — New Project". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Standards and Major Progress for a Made-in-America National Network of Electric Vehicle Chargers". The White House. 15 February 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Eco Tech: E-Move Charging Station fuels just about everything with solar energy". Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Sanya Skypump: World's first wind-fueled EV charging station – Digital Trends". Digital Trends. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Vorrath, Sophie (24 March 2021). "World's first tidal energy powered EV charger launched in Shetland". The Driven. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Pesce, Federico (24 May 2023). "Addio colonnine, ecco la prima autostrada che ricarica le auto elettriche in movimento" [Goodbye columns, here is the first highway that recharges electric cars on the go]. la Repubblica (in Italian). Rome, Italy. Retrieved 15 May 2024. English translation

- ^ "Sweden is building the world's first permanent electrified road for EVs to charge while driving". euronews.com.

- ^ "Electric road E20, Hallsberg–Örebro". Trafikverket. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

Charging station

View on GrokipediaOverview and Fundamentals

Definition and Core Principles

A charging station, technically termed electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE), comprises the hardware that connects an electric vehicle to a power source, regulating the flow of electricity to recharge the vehicle's battery while incorporating safety protocols to mitigate risks such as electrical faults or unauthorized access.[10] The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) defines EVSE as the system establishing and managing the electrical circuit between the supply and the vehicle, distinct from the vehicle's onboard charger.[11] At its core, the charging process relies on the transfer of electrical energy from the grid—predominantly alternating current (AC)—to the direct current (DC) required by lithium-ion batteries, achieved either via the vehicle's internal converter for slower AC charging or the station's rectifier for rapid DC delivery.[12] This conversion adheres to principles of electrical engineering where power delivery, measured in kilowatts (kW), determines recharge efficiency, with higher currents and voltages enabling faster charging but necessitating robust thermal management to prevent battery degradation.[13] Fundamental safety interlocks, including a control pilot signal for vehicle-station communication and circuit interrupt devices for ground faults, ensure operational integrity, as standardized by bodies like SAE and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).[14] These mechanisms verify connection viability, monitor current limits, and terminate power if anomalies arise, underpinning the causal chain from power input to safe energy storage.[15]Types and Classifications

Electric vehicle charging stations are classified primarily by the electrical current type supplied—alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC)—and by standardized power delivery levels that determine charging speed and application suitability. AC stations deliver alternating current from the grid, relying on the vehicle's onboard converter to produce direct current for the battery, whereas DC stations convert AC to DC off-board and supply it directly, enabling higher power throughput and reduced charging times. This distinction arises from grid infrastructure limitations and vehicle design constraints, with AC suited for slower, extended sessions and DC for rapid replenishment.[16][17] In North America, the SAE J1772 standard delineates AC charging into Level 1 and Level 2 categories based on voltage and power output. Level 1 chargers utilize standard 120-volt household outlets to provide 1.0 to 1.9 kilowatts (kW), achieving about 3-5 miles of range per hour of charging, ideal for opportunistic or overnight use in residential settings but requiring 40-50 hours or more for an 80% charge on battery electric vehicles (BEVs) with 60-100 kWh batteries. Level 2 chargers operate at 208-240 volts across single- or three-phase circuits, delivering 3.3 to 19.2 kW and adding 10-60 miles of range per hour, commonly deployed in homes, workplaces, and public lots for 4-10 hour full charges.[4][18][19] DC fast charging, designated as Level 3 under SAE guidelines, encompasses high-power systems from 50 kW to 350 kW or higher, capable of delivering 100-300 miles of range in 20-60 minutes by directly feeding the battery, though actual rates depend on vehicle acceptance limits, battery state, and thermal management. These are subdivided by connector protocols such as SAE Combined Charging System (CCS), CHAdeMO, and Tesla's North American Charging Standard (NACS, now SAE J3400), with power scaling from legacy 50 kW units to ultra-fast 350 kW installations along highways.[1][4] Internationally, the IEC 61851 standard employs operational modes rather than numeric levels: Mode 1 for unmanaged household AC (up to 16 amperes), Mode 2 for portable AC with in-cable control, Mode 3 for fixed AC stations with safety interlocks (up to 63 amperes per phase), and Mode 4 for DC fast charging. This framework aligns with regional voltage norms, such as Europe's 230-400 volts, and supports interoperability via Type 1 (SAE J1772 equivalent) or Type 2 connectors for AC, extending to CCS or CHAdeMO for DC. Additional classifications consider installation location—residential, commercial, public curbside, or fleet depots—and vehicle class, with heavy-duty stations often exceeding 500 kW for trucks and buses to accommodate larger batteries.[20][21]| Classification | Current Type | Typical Power Range | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (SAE Mode 1/2 equivalent) | AC | 1-2 kW | Residential overnight, portable |

| Level 2 (SAE Mode 3 equivalent) | AC | 3-19 kW | Home, workplace, public parking |

| Level 3/DC Fast (SAE/IEC Mode 4) | DC | 50-350+ kW | Highways, travel corridors, commercial hubs |

Technical Specifications

Charging Levels and Power Delivery

Level 1 charging, the slowest and most basic form, utilizes standard 120-volt alternating current (AC) household outlets to deliver approximately 1 to 2 kilowatts (kW) of power, adding roughly 2 to 4 miles of range per hour for most battery electric vehicles (BEVs).[4][1] This level relies on the vehicle's onboard charger to convert AC to direct current (DC) for the battery, with full charges for typical BEVs taking 40 to 50 hours or more from empty to 80% capacity.[4] It is suitable for overnight charging of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), which require only 5 to 6 hours, but impractical for frequent long-distance travel due to low power throughput.[4] Level 2 charging operates at 208 to 240 volts AC, providing 3 to 19.2 kW of power depending on the charger's amperage (typically 16 to 80 amps) and the vehicle's onboard converter capacity, enabling 10 to 60 miles of range added per hour.[1][4] This level reduces charging times to 4 to 10 hours for BEVs from empty to 80%, making it the standard for residential, workplace, and public stations where infrastructure allows higher amperage circuits.[4] Power delivery is governed by standards like SAE J1772 in North America, which specifies single-phase AC with pilot signaling for safe connection and current negotiation.[22] Direct current fast charging (DCFC), often termed Level 3, bypasses the vehicle's onboard converter by supplying high-voltage DC directly to the battery at 50 kW or higher, with common stations delivering 50 to 350 kW to achieve 100 to 200+ miles of range in 30 minutes.[1][4] Power levels taper as batteries approach full capacity to prevent overheating, and actual delivery is limited by the vehicle's maximum acceptance rate, cable capabilities, and grid connection— for instance, many stations operate at 150 to 250 kW in practice despite theoretical peaks.[1] This enables rapid en-route charging but requires robust three-phase infrastructure and generates more heat, necessitating liquid-cooled cables for outputs above 200 kW.[1]| Charging Level | Voltage | Typical Power (kW) | Approx. Time to 80% (BEV, 60 kWh battery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (AC) | 120 V | 1–2 | 40–50+ hours |

| Level 2 (AC) | 208–240 V | 3–19.2 | 4–10 hours |

| DCFC (Level 3) | Variable DC | 50–350 | 20–40 minutes |

AC versus DC Conversion Mechanics

In alternating current (AC) charging, the electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE) supplies grid-derived AC power—typically single-phase at 120–240 volts (around 7 kW for home setups) or three-phase up to 480 volts (up to 22 kW)—to the vehicle via standardized connectors, a process ideal for prolonged parking scenarios that requires hours for a full charge and imposes lower stress on the battery.[23] The vehicle's onboard charger (OBC) then performs the necessary conversion to direct current (DC), as lithium-ion batteries require DC for safe and efficient charging.[24] This OBC integrates two primary stages: an AC-DC rectifier, often incorporating active power factor correction (PFC) circuitry to minimize harmonic distortion and align input current with voltage for grid compliance, followed by a DC-DC converter that regulates output voltage to match the battery pack's nominal range (e.g., 300–800 volts).[23] A DC-link capacitor stabilizes the intermediate DC bus between stages, while isolation transformers in the DC-DC phase provide galvanic separation for safety against ground faults.[23] Power levels are constrained by OBC capacity, typically 3.3–22 kilowatts (kW), limiting charge rates due to vehicle weight, thermal management, and component sizing.[23] Direct current (DC) charging shifts the conversion process to the off-board EVSE, enabling higher power delivery by bypassing the OBC.[23] Here, the station draws three-phase AC from the grid (often 400–480 volts), rectifies it to an intermediate DC bus via a front-end AC-DC converter with PFC—commonly a diode bridge or Vienna rectifier for efficiency—and then employs a high-power DC-DC converter to adjust voltage and current precisely to the battery's requirements, communicated via protocols like ISO 15118.[23] This DC-DC stage, frequently using topologies such as dual active bridges or interleaved boost converters, handles wide input-output voltage swings (200–1000 volts) and currents up to 500 amperes, supporting rates from 50 kW to over 350 kW.[25] High-frequency isolation transformers mitigate risks from direct grid-battery connection, and modular designs with parallel modules enhance scalability and redundancy.[23] Vehicle-side control limits power based on state-of-charge, temperature, and battery chemistry to prevent degradation.[24] The core distinction lies in conversion locus: onboard for AC prioritizes convenience for lower-power, overnight charging but incurs efficiency losses (85–95%) from vehicle-integrated components and restricts scalability due to space constraints.[23] Offboard DC conversion achieves higher efficiencies (up to 97%) and faster rates by leveraging stationary, larger-capacity hardware, though it demands robust grid infrastructure and incurs higher upfront station costs.[25] Both methods incorporate safety interlocks, such as pilot signals for handshaking and ground fault detection, but DC systems require additional insulation monitoring owing to elevated voltages.[23] Emerging bidirectional converters in both setups enable vehicle-to-grid (V2G) functionality, inverting DC to AC for grid support, though adoption remains limited by regulatory and hardware standardization as of 2024.[23]Determinants of Charging Duration