Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Endurance

View on Wikipedia

Endurance (also related to sufferance, forbearance, resilience, constitution, fortitude, persistence, tenacity, steadfastness, perseverance, stamina, and hardiness) is the ability of an organism to exert itself and remain active for a long period of time, as well as its ability to resist, withstand, recover from and have immunity to trauma, wounds, or fatigue.

The term is often used in the context of aerobic or anaerobic exercise. The definition of "long" varies according to the type of exertion – minutes for high intensity anaerobic exercise, hours or days for low intensity aerobic exercise. Training for endurance can reduce endurance strength[verification needed][1] unless an individual also undertakes resistance training to counteract this effect.

When a person is able to accomplish or withstand more effort than previously, their endurance is increasing. To improve their endurance they may slowly increase the amount of repetitions or time spent; in some exercises, more repetitions taken rapidly improve muscle strength but have less effect on endurance.[2] Increasing endurance has been proven to release endorphins resulting in a positive mind.[citation needed] The act of gaining endurance through physical activity decreases anxiety, depression, and stress, or any chronic disease[dubious – discuss].[3] Although a greater endurance can assist the cardiovascular system this does not imply that endurance is guaranteed to improve any cardiovascular disease.[4] "The major metabolic consequences of the adaptations of muscle to endurance exercise are a slower utilization of muscle glycogen and blood glucose, a greater reliance on fat oxidation, and less lactate production during exercise of a given intensity."[5]

The term stamina is sometimes used synonymously and interchangeably with endurance. Endurance may also refer to an ability to persevere through a difficult situation, to "endure hardship".

In military settings, endurance is the ability of a force[clarification needed] to sustain high levels of combat potential relative to its opponent over the duration of a campaign.[6]

Philosophy

[edit]Aristotle noted similarities between endurance and self control: To have self control is to resist the temptation of things that seem immediately appealing, while to endure is to resist the discouragement of things that seem immediately uncomfortable.[7]

Endurance training

[edit]Different types of endurance performance can be trained in specific ways. Adaptation of exercise plans should follow individual goals.

Calculating the intensity of exercise the individual capabilities should be considered[by whom?]. Effective training starts within half the individual performance capability.[further explanation needed] Performance capability is expressed by maximum heart rate. Best[clarification needed] results can be achieved in the range between 55% and 65% of maximum heart rate. Aerobic, anaerobic and further thresholds are not to be mentioned within extensive endurance exercises.[why?] Training intensity is measured via the heart rate.[8]

Endurance-trained effects are mediated by epigenetic mechanisms

[edit]Between 2012 and 2019 at least 25 reports indicated a major role of epigenetic mechanisms in skeletal muscle responses to exercise.[9]

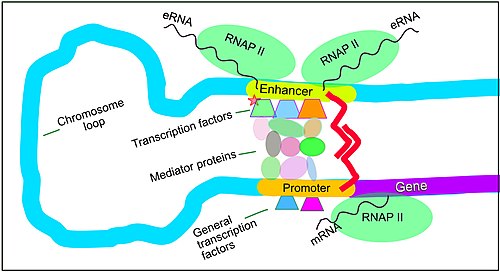

An active enhancer regulatory region is enabled to interact with the promoter region of its target gene by formation of a chromosome loop. This can allow initiation of messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis by RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) bound to the promoter at the transcription start site of the gene. The loop is stabilized by one architectural protein anchored to the enhancer and one anchored to the promoter, and these proteins are joined together to form a dimer (red zigzags). Specific regulatory transcription factors bind to DNA sequence motifs on the enhancer. General transcription factors bind to the promoter. When a transcription factor is activated by a signal (here indicated as phosphorylation shown by a small red star on a transcription factor on the enhancer) the enhancer is activated and can now activate its target promoter. The active enhancer is transcribed on each strand of DNA in opposite directions by bound RNAP IIs. Mediator (a complex consisting of about 26 proteins in an interacting structure) communicates regulatory signals from the enhancer DNA-bound transcription factors to the promoter.

Gene expression in muscle is largely regulated, as in tissues generally, by regulatory DNA sequences, especially enhancers. Enhancers are non-coding sequences in the genome that activate the expression of distant target genes,[10] by looping around and interacting with the promoters of their target genes[11] (see Figure "Regulation of transcription in mammals"). As reported by Williams et al.,[12] the average distance in the loop between the connected enhancers and promoters of genes is 239,000 nucleotide bases.

Endurance exercise-induced long-term alteration of gene expression by histone acetylation or deacetylation

[edit]

DNA in the nucleus generally consists of segments of 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around nucleosomes connected to adjacent nucleosomes by linker DNA. Nucleosomes consist of four pairs of histone proteins in a tightly assembled core region plus up to 30% of each histone remaining in a loosely organized polypeptide tail (only one tail of each pair is shown). The pairs of histones, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, each have lysines (K) in their tails, some of which are subject to post-translational modifications consisting, usually, of acetylations [Ac] and methylations {me}. The lysines (K) are designated with a number showing their position as, for instance, (K4), indicating lysine as the 4th amino acid from the amino (N) end of the tail in the histone protein. The particular acetylations [Ac] and methylations {Me} shown are those that occur on nucleosomes close to, or at, some DNA regions undergoing transcriptional activation of the DNA wrapped around the nucleosome.

After exercise, epigenetic alterations to enhancers alter long-term expression of hundreds of muscle genes. This includes genes producing proteins and other products secreted into the systemic circulation, many of which may act as endocrine messengers.[12] Of 817 genes with altered expression, 157 (according to Uniprot) or 392 (according to Exocarta) of the proteins produced according to those genes were known to be secreted from the muscles. Four days after an endurance type of exercise, many genes have persistently altered epigenetically regulated expression.[12] Four pathways altered were in the platelet/coagulation system, the cognitive system, the cardiovascular system, and the renal system. Epigenetic regulation of these genes was indicated by epigenetic alterations in the distant upstream DNA regulatory sequences of the enhancers of these genes. [citation needed]

Up-regulated genes had epigenetic acetylations added at histone 3 lysine 27 (H3k27ac) of nucleosomes located at the enhancers controlling those up-regulated genes, while down-regulated genes had epigenetic acetylations removed from H3K27 in nucleosomes located at the enhancers that control those genes (see Figure "A nucleosome with histone tails set for transcriptional activation"). Biopsies of the vastus lateralis muscle showed expression of 13,108 genes at baseline before an exercise training program. Six sedentary 23-year-old Caucasian males provided vastus lateralis biopsies before entering an exercise program (six weeks of 60-minute sessions of riding a stationary cycle, five days per week). Four days after the exercise program was completed, biopsies of the same muscles had altered gene expression, with 641 genes up-regulated and 176 genes down-regulated. Williams et al.[12] identified 599 enhancer-gene interactions, covering 491 enhancers and 268 genes, where both the enhancer and the connected target gene were coordinately either upregulated or downregulated after exercise training.

Endurance exercise-induced alteration to gene expression by DNA methylation or demethylation

[edit]Endurance muscle training also alters muscle gene expression through epigenetic DNA methylation or de-methylation of CpG sites within enhancers.[13] In a study by Lindholm et al.,[13] twenty-three 27-year-old, sedentary, male and female volunteers had endurance training on only one leg during three months. The other leg was used as an untrained control leg. Skeletal muscle biopsies from the vastus lateralis were taken both before training began and 24 hours after the last training session from each of the legs. The endurance-trained leg, compared to the untrained leg, had significant DNA methylation changes at 4,919 sites across the genome. The sites of altered DNA methylation were predominantly in enhancers. Transcriptional analysis, using RNA sequencing, identified 4,076 differentially expressed genes.[citation needed]

The transcriptionally upregulated genes were associated with enhancers that had a significant decrease in DNA methylation, while transcriptionally downregulated genes were associated with enhancers that had increased DNA methylation. In this study, the differentially methylated positions in enhancers with increased methylation were mainly associated with genes involved in structural remodeling of the muscle and glucose metabolism. The differentially decreased methylated positions in enhancers were associated with genes functioning in inflammatory/immunological processes and transcriptional regulation.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hickson, R.C. (1980). "Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance over a long period". European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 45 (2–3). Springer Verlag: 255–63. doi:10.1007/BF00421333. PMID 7193134. S2CID 22934619.

- ^ "Muscular Strength and Endurance". HealthLinkBC: Physical Activity Services. 29 November 2016. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Hansen, Cheryl J.; et al. (2001). "Exercise Duration and Mood State: How Much Is Enough to Feel Better?" (PDF). Health Psychology. 20 (4): 267–75. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.20.4.267. PMID 11515738. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ Iwasaki, Ken-ichi; Zhang, Rong; Zuckerman, Julie H.; Levine, Benjamin D. (2003-10-01). "Dose-response relationship of the cardiovascular adaptation to endurance training in healthy adults: how much training for what benefit?". Journal of Applied Physiology. 95 (4): 1575–1583. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00482.2003. ISSN 8750-7587. PMID 12832429. S2CID 8493563. Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ Holloszy, J.O.; Coyle, E.F. (1 April 1984). "Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise and their metabolic consequences". Journal of Applied Physiology. 56 (4): 831–838. doi:10.1152/jappl.1984.56.4.831. PMID 6373687. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Headquarter, Department of the Army (1994), Leader's Manual for Combat Stress Control, FM 22-51, Washington D.C.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. VII.7.

- ^ Tomasits, Josef; Haber, Paul (2008). Leistungsphysiologie – Grundlagen für Trainer, Physiotherapeuten und Masseure (in German). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-211-72019-6.

- ^ Widmann M, Nieß AM, Munz B (April 2019). "Physical Exercise and Epigenetic Modifications in Skeletal Muscle". Sports Med. 49 (4): 509–523. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01070-4. PMID 30778851. S2CID 73481438.

- ^ Panigrahi A, O'Malley BW (April 2021). "Mechanisms of enhancer action: the known and the unknown". Genome Biol. 22 (1): 108. doi:10.1186/s13059-021-02322-1. PMC 8051032. PMID 33858480.

- ^ Marsman J, Horsfield JA (2012). "Long distance relationships: enhancer-promoter communication and dynamic gene transcription". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1819 (11–12): 1217–27. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.10.008. PMID 23124110.

- ^ a b c d Williams K, Carrasquilla GD, Ingerslev LR, Hochreuter MY, Hansson S, Pillon NJ, Donkin I, Versteyhe S, Zierath JR, Kilpeläinen TO, Barrès R (November 2021). "Epigenetic rewiring of skeletal muscle enhancers after exercise training supports a role in whole-body function and human health". Mol Metab. 53 101290. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101290. PMC 8355925. PMID 34252634.

- ^ a b Lindholm ME, Marabita F, Gomez-Cabrero D, Rundqvist H, Ekström TJ, Tegnér J, Sundberg CJ (December 2014). "An integrative analysis reveals coordinated reprogramming of the epigenome and the transcriptome in human skeletal muscle after training". Epigenetics. 9 (12): 1557–69. doi:10.4161/15592294.2014.982445. PMC 4622000. PMID 25484259.

Endurance

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Concepts

General Definition

Endurance refers to the ability to withstand hardship, adversity, or stress, particularly the capacity to sustain prolonged effort or activity without failure. This distinguishes it from short-burst capabilities like strength or power, which involve maximal output over brief periods rather than persistence over time.[1][2] The word "endurance" derives from the Latin indurare, meaning "to harden" or "to make firm," via Old French endurer; it entered English in the late 15th century, initially denoting a lasting quality or the power to continue enduring a condition.[5][6] Across disciplines, endurance encompasses sustained metabolic activity in human biology that supports extended physical work; psychological persistence under duress, involving emotional regulation and focus to maintain effort; and, in engineering, material durability against repeated loads—though primary emphasis lies on human physical and mental contexts.[4][7][8] Common examples include long-distance running, where individuals sustain aerobic effort over hours, or prolonged concentration during demanding work tasks, testing mental stamina against fatigue. Endurance manifests in various types, such as physical subtypes explored further elsewhere.[9]Types of Endurance

Endurance manifests in various forms depending on the physiological, psychological, or environmental demands placed on an individual. Broadly, it is classified into physical, mental, and other specialized types, each addressing distinct capacities for sustained effort. These categories highlight how endurance adapts to different contexts, from bodily exertion to cognitive persistence, without overlapping into training methodologies or deeper biological processes. Physical endurance encompasses subtypes that differentiate based on energy utilization and muscle involvement. Aerobic endurance relies on oxygen-dependent processes to sustain prolonged, moderate-intensity activities, such as marathon running, where the body efficiently uses fat and carbohydrates for energy over hours. Anaerobic endurance, in contrast, supports short, high-intensity bursts without immediate oxygen reliance, exemplified by sprint intervals in track events, drawing primarily from stored phosphocreatine and glycogen. Muscular endurance refers to the localized ability of specific muscle groups to perform repeated contractions against resistance over time, as seen in activities like weightlifting sets or climbing, focusing on fatigue resistance in targeted areas. The physiological basis of these physical types involves varying metabolic pathways, with aerobic favoring oxidative metabolism and anaerobic emphasizing glycolytic efforts. Mental endurance involves psychological dimensions that enable sustained mental effort amid challenges. Emotional endurance denotes the capacity to maintain motivation and emotional stability during prolonged setbacks or stress, crucial for athletes enduring competitive losses or professionals handling extended crises. Cognitive endurance, meanwhile, pertains to preserving attention, decision-making, and mental acuity over extended periods, such as in long-duration tasks like air traffic control or marathon strategy sessions. Other types of endurance address broader or specialized adaptations. Environmental endurance involves acclimating to extreme conditions like high heat, cold, or altitude, enabling sustained performance in harsh settings, for instance, ultramarathoners navigating desert races. Systemic endurance differentiates between whole-body integration, as in cross-country skiing demanding coordinated cardiovascular and muscular efforts, and localized forms, which isolate to specific regions like grip strength in rowing.| Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Endurance | Sustained effort using oxygen for energy production in moderate activities. | Marathon running |

| Anaerobic Endurance | High-intensity bursts relying on non-oxygen energy stores for short durations. | 400-meter sprints |

| Muscular Endurance | Repeated contractions in specific muscles to resist fatigue locally. | Push-up repetitions |

| Emotional Endurance | Maintaining motivation and emotional regulation amid prolonged adversity. | Enduring team defeats |

| Cognitive Endurance | Sustained focus and mental processing over extended tasks. | All-night exam studying |

| Environmental Endurance | Adaptation to physical stressors like temperature or elevation extremes. | High-altitude trekking |

| Systemic Endurance | Whole-body or localized coordination for prolonged integrated efforts. | Long-distance cycling |

Physical Endurance

Physiological Mechanisms

Physical endurance relies on intricate energy pathways that sustain prolonged muscular activity. Aerobic metabolism predominates during endurance exercise, utilizing oxygen to generate ATP through the Krebs cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle) and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, enabling efficient fat and carbohydrate oxidation for sustained energy production.[10] In contrast, anaerobic metabolism via glycolysis provides rapid ATP but leads to lactate accumulation when oxygen demand exceeds supply, typically during higher intensities, contributing to fatigue if prolonged.[10] These pathways shift dynamically based on exercise intensity, with aerobic processes supporting activities like marathon running where anaerobic contributions remain minimal (typically less than 2% of total energy).[11] Key physiological systems adapt to enhance endurance capacity. The cardiovascular system increases stroke volume—the volume of blood ejected per heartbeat—and maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂ max), often reaching 70-85 ml/kg/min in elite athletes, to improve oxygen delivery to muscles.[10] The respiratory system bolsters oxygen uptake through enhanced ventilatory efficiency, ensuring adequate arterial oxygenation despite rising demands.[12] Muscular adaptations include elevated mitochondrial density for improved aerobic energy production and capillary growth (angiogenesis) to facilitate better nutrient delivery and waste removal, particularly in type I slow-twitch fibers.[13] Recent research as of 2025 has identified core body temperature regulation as a fundamental limiter in ultra-endurance performance, where rising heat stress can cap sustained effort around 35 km in marathons, alongside brain myelin plasticity as an adaptive response to prolonged exercise aiding neural efficiency.[14] Hormonal factors modulate these processes to delay fatigue onset. Adrenaline (epinephrine) surges during endurance exercise, stimulating glycogenolysis and lipolysis to mobilize energy substrates and enhance cardiovascular output.[15] Cortisol rises above 60% VO₂ max intensities, promoting gluconeogenesis and reducing inflammation to sustain metabolic balance.[15] Endorphins, released via hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation, provide analgesia and mitigate perceived exertion, allowing continued effort.[15] Fatigue in endurance exercise arises from central and peripheral thresholds. Central fatigue involves brain signaling reductions in motor unit recruitment due to neurotransmitter imbalances (e.g., serotonin accumulation), leading to diminished voluntary drive.[16] Peripheral fatigue occurs at the muscle level from metabolite buildup, such as lactate and hydrogen ions, impairing contractile function.[16] The lactate threshold (LT), a critical marker of endurance capacity, is the exercise intensity at which blood lactate begins to accumulate substantially above baseline levels (often around 2–4 mmol/L, varying by individual fitness), indicating a shift toward greater anaerobic metabolism and the onset of accelerated fatigue.[17]Training Principles

Training principles for developing physical endurance emphasize structured approaches that promote physiological adaptations while minimizing injury risk. The core principles include progressive overload, which involves gradually increasing the duration, intensity, or frequency of exercise to continually challenge the body and drive improvements in aerobic capacity; specificity, which ensures that training mirrors the demands of the target activity, such as incorporating running for runners to enhance sport-specific endurance; and recovery, which incorporates rest periods and active recovery to prevent overtraining syndrome and allow for supercompensation.[18][19] These principles, foundational to exercise prescription, guide the systematic enhancement of endurance without excessive fatigue.[18] Key methods for building endurance include interval training, which alternates high-intensity bursts (e.g., 80-90% of maximum heart rate for 1-5 minutes) with recovery periods to improve VO2 max and lactate threshold; continuous training, characterized by steady-state efforts at moderate intensity (60-80% of maximum heart rate) for extended durations to build aerobic base and fat oxidation; and cross-training, which incorporates varied activities like cycling or swimming to reduce overuse injuries while maintaining cardiovascular fitness.[13] These methods can be combined based on individual goals, with interval training particularly effective for performance gains in events lasting 30 minutes to 2 hours.[13] Periodization structures training into phases to optimize adaptations and peak performance, with two primary models: linear periodization, which features a steady build-up of volume followed by intensity (e.g., increasing weekly mileage progressively before tapering); and undulating periodization, which varies intensity and volume weekly (e.g., alternating high-volume/low-intensity and low-volume/high-intensity days) to enhance recovery and reduce plateaus.[20] Research indicates undulating models can enhance recovery and reduce training plateaus through frequent stimulus variation, with no significant differences in overall strength or endurance gains compared to linear models in most studies.[21] An example 12-week marathon plan using linear periodization might outline as follows:- Weeks 1-4 (Base Building): Focus on volume with 3-4 runs per week, totaling 20-30 miles, including one long run increasing from 6 to 10 miles at easy pace.

- Weeks 5-8 (Intensity Development): Introduce intervals (e.g., 4x800m at tempo pace) and tempo runs, peaking at 35-40 miles weekly with a 14-mile long run.

- Weeks 9-11 (Peak Phase): Maintain high volume (40-45 miles) with race-pace simulations, longest run at 18-20 miles.

- Week 12 (Taper): Reduce volume by 40-60% while preserving intensity to ensure freshness for the race.[22]