Recent from talks

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Contribute something

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Erotic dance.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Erotic dance

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2013) |

An erotic dance is a dance that provides erotic entertainment with the objective to erotically stimulate or sexually arouse viewers. Erotic dance is one of several major dance categories based on purpose, such as ceremonial, competitive, performance and social dance.

The erotic dancer's clothing is often minimal and may be gradually removed to be partially or completely naked. In some areas where exposure of nipples[1] or genitals is illegal, a dancer may respectively wear pasties or a g-string to stay within the law.

Nudity, though a common feature, is not a requirement of erotic dance. The culture and the ability of the human body is a significant aesthetic component in many dance styles.

Genres

[edit]- Can-can

- Cage dance

- Go-go dance

- Hoochie coochie

- Mujra

- Sexercise

- Striptease (Exotic dancer)

- Pole dance

- Bubble dance

- Fan dance

- Gown-and-glove striptease

- Lap dance

- Couch dance

- Contact dance

- Limo lap dance

- Dance of the seven veils

- Table dance

- Grinding

- Neo-Burlesque

- Twerking

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court refuses to 'Free the Nipple' in topless women case". Reuters. 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- McMahon, Tiberius. Uniting Exotic And Erotic Dancers Worldwide, GlobalSecurityReport.com, 2006.

External links

[edit] Media related to Erotic dancers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Erotic dancers at Wikimedia Commons

Erotic dance

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Erotic dance refers to performative movements explicitly crafted to elicit sexual arousal in an audience by emphasizing the dancer's body through sensual gestures, often involving the progressive removal of clothing or intimate physical proximity.[1][2] This form of expression traces its origins to prehistoric fertility rituals and ancient cultural practices, where rhythmic bodily displays served functions tied to mating signals and communal sexuality, as evidenced by cross-cultural anthropological records.[3] In modern contexts, it manifests primarily in commercial settings like strip clubs, where exotic dancers engage in striptease, lap dances, and pole routines to paying patrons, generating substantial economic activity within the adult entertainment sector.[4]

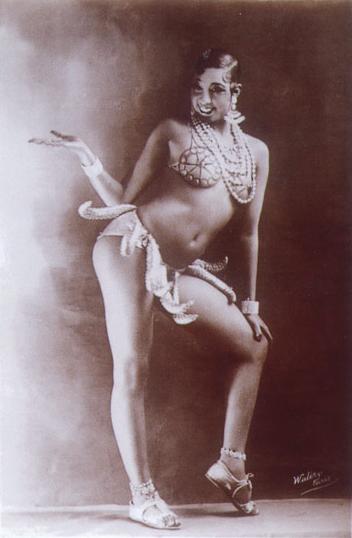

Historically, erotic dance has intersected with broader social dynamics, from colonial exhibitions framing "exotic" bodies for Western gazes to burlesque revues in early 20th-century theaters, evolving amid shifting legal and moral frameworks that regulate nudity and public sexuality.[2] Notable figures, such as performer Josephine Baker, elevated elements of erotic choreography to mainstream acclaim through innovative spectacles blending athleticism and allure, influencing perceptions of racialized sensuality in performance arts. Empirical analyses of the industry highlight its role in sexual selection and commodification, where dancers leverage physical capital for income, yet face systemic vulnerabilities including workplace violence, health hazards from substance use, and precarious labor conditions that challenge narratives of unmitigated empowerment.[5] Controversies persist regarding its effects on participants and society, with peer-reviewed literature documenting both agency in bodily expression and causal links to exploitation under patriarchal demand structures, underscoring the tension between individual volition and market-driven objectification.[4][3]