Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

European emission standards

View on Wikipedia

The European emission standards are vehicle emission standards that regulate pollution from the use of new land surface vehicles sold in the European Union and European Economic Area member states and the United Kingdom, and ships in European territorial waters.[1][2] These standards target air pollution from exhaust gases, brake dust, and tyre rubber pollution, and are defined through a series of European Union directives that progressively introduce stricter limits to reduce environmental impact.

Euro 7, agreed in 2024 and due to come into force in 2026,[3][4] includes non-exhaust emissions such as particulates from tyres and brakes.[5][6][7][8] Until 2030 fossil fueled vehicles are allowed to have dirtier brakes than electric vehicles.[9]: 5

Background

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

In the European Union, emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), total hydrocarbon (THC), non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHC), carbon monoxide (CO) and particulate matter (PM) are regulated for most vehicle types, including cars, trucks (lorries), locomotives, tractors and similar machinery, barges, but excluding seagoing ships and aeroplanes.[10][11] For each vehicle type, different standards apply. Compliance is determined by running the engine at a standardised test cycle.[12] Non-compliant vehicles cannot be sold in the EU, but new standards do not apply to vehicles already on the roads.[13] No use of specific technologies is mandated to meet the standards, though available technology is considered when setting the standards. New models introduced must meet current or planned standards, but minor lifecycle model revisions may continue to be offered with pre-compliant engines.

Along with emissions standards, the European Union has also mandated a number of computer on-board diagnostics for the purposes of increasing safety for drivers. These standards are used in relation to the emissions standards.

During the early 2000s, Australia began harmonising Australian Design Rule certification for new motor vehicle emissions with Euro categories. Euro III was introduced on 1 January 2006 and is progressively being introduced to align with European introduction dates.

Euro 7 was formally given approval by EU countries in April 2024.[8]

Toxic emission: stages and legal framework

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: euro 7 per https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ID-116-–-Euro-7-standard_final.pdf. (March 2024) |

The stages are typically referred to as Euro 1, Euro 2, Euro 3, Euro 4, Euro 5 and Euro 6 for Light Duty Vehicle standards.

The legal framework consists in a series of directives, each amendments to the 1970 Directive 70/220/EEC.[14] The following is a summary list of the standards, when they come into force, what they apply to, and which EU directives provide the definition of the standard.

- Euro 1 (1992):

- For passenger cars—91/441/EEC.[15]

- Also for passenger cars and light lorries—93/59/EEC.

- Euro 2 (1996) for passenger cars—94/12/EC (& 96/69/EC)

- For motorcycle—2002/51/EC (row A)[16]—2006/120/EC

- Euro 3 (2000) for any vehicle—98/69/EC[17]

- For motorcycle—2002/51/EC (row B)[16]—2006/120/EC

- Euro 4 (2005) for any vehicle—98/69/EC (& 2002/80/EC)

- Euro 5 (2009) for light passenger and commercial vehicles—715/2007/EC[18]

- Euro 6 (2014) for light passenger and commercial vehicles—459/2012/EC[19] and 2016/646/EU[20]

- Euro 7 (2030 to 2031)[21][22]

These limits supersede the original directive on emission limits 70/220/EEC.

The classifications for vehicle category are defined by:[23]

- Commission Directive 2001/116/EC of 20 December 2001, adapting to technical progress Council Directive 70/156/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the type-approval of motor vehicles and their trailers[24][25]

- Directive 2002/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 March 2002 relating to the type-approval of two or three-wheeled motor vehicles and repealing Council Directive 92/61/EEC

Emission standards for passenger cars

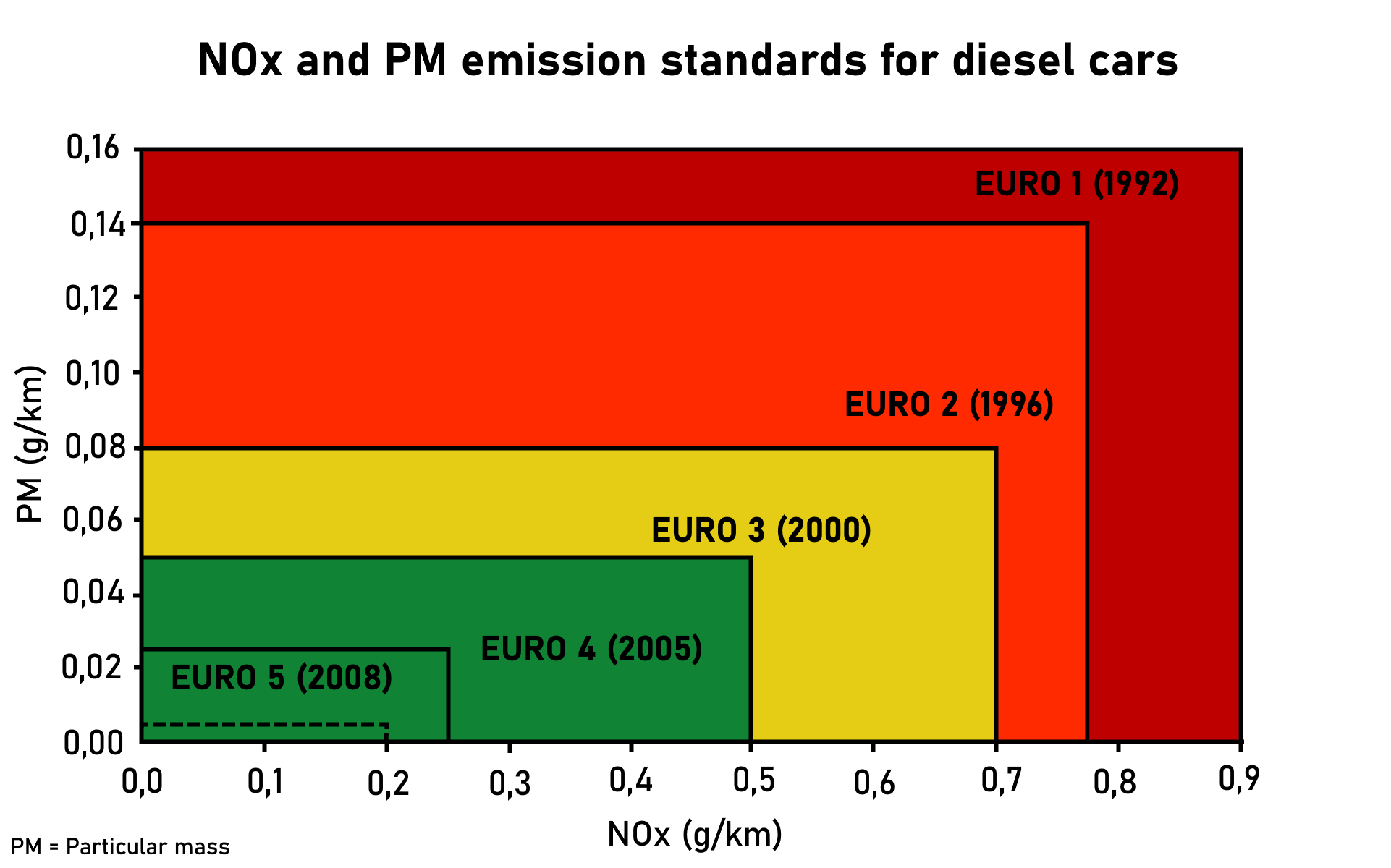

[edit]Emission standards for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles are summarized in the following tables. Since the Euro 2 stage, EU regulations introduce different emission limits for diesel and petrol vehicles. Diesels have more stringent CO standards but are allowed higher NOx emissions. Petrol-powered vehicles are exempted from particulate matter (PM) standards through to the Euro 4 stage, but vehicles with direct injection engines are subject to a limit of 0.0045 g/km for Euro 5 and Euro 6. A particulate number standard (P) or (PN) has been introduced in 2011 with Euro 5b for diesel engines and, in 2014, with Euro 6 for petrol engines.[26][27][28]

From a technical perspective, European emissions standards do not reflect everyday usage of the vehicle as manufacturers are allowed to lighten the vehicle by removing the back seats, improve aerodynamics by taping over grilles and door handles, or reduce the load on the generator by switching off the headlights, the passenger compartment fan, or simply disconnecting the alternator which charges the battery.[29]

| Tier | Date (type approval) | Date (first registration) | CO | THC | NMHC | NH3 | NOx | HC+NOx | PM | PN [#/km] | Brake PM10[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | |||||||||||

| Euro 1[c] | July 1992 | January 1993 | 2.72 (3.16) | – | – | – | – | 0.97 (1.13) | 0.14 (0.18) | – | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1996 | January 1997 | 1.0 | – | – | – | – | 0.7 | 0.08 | – | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | January 2001 | 0.66 | – | – | – | 0.500 | 0.56 | 0.05 | – | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | January 2006 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.250 | 0.30 | 0.025 | – | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2009 | January 2011 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.005 | – | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6b | September 2014 | September 2015 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2018 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2017 | September 2019 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6d | January 2020 | January 2021 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 7 | 0.50 | – | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011[d] | 0.007 | ||

| Petrol | |||||||||||

| Euro 1[c] | July 1992 | January 1993 | 2.72 (3.16) | – | – | – | – | 0.97 (1.13) | – | – | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1996 | January 1997 | 2.2 | – | – | – | – | 0.5 | – | – | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | January 2001 | 2.3 | 0.20 | – | – | 0.150 | – | – | – | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | January 2006 | 1.0 | 0.10 | – | – | 0.080 | – | – | – | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2009 | January 2011 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.005[e] | – | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | – | – |

| Euro 6b | September 2014 | September 2015 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | 6×1011[f] | – |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2018 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2017 | September 2019 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6d | January 2020 | January 2021 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | 6×1011 | – |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.068 | – | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[e] | 6×1011 | – |

| |||||||||||

Emission standards for motor cycles (two and three wheelers) – L-category vehicles

[edit]The Euro emissions regulations for two and three wheelers (motorcycles) were first introduced in 1999 — some seven years after the cars were first regulated. In further difference to passenger cars (where three-way catalytic converters were de facto required from Euro I), it was first with the introduction of the Euro III emissions standard in 2006 that motorcycles were de facto required to use three-way catalytic converters. With the introduction of Euro V, standard two-stroke engine motorcycles are challenged by the strict HC and PM emissions limits. It is expected that technologies such as direct injection, combined with petrol particulate filters, could be needed for these motorcycle engine types to meet the Euro V demands.[30][31][32]

| Standard | Date | CO (g/km) | NOx (g/km) | HC (g/km) | PM (g/km) | NMHC (g/km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro I | 1999 | 13.0 | 0.3 | 3.0 | ||

| Euro II | 2003 | 5.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Euro III | 2006 | 2.0 | 0.15 | 0.3 | ||

| Euro IV | 2016 | 1.14 | 0.09 | 0.17 | ||

| Euro V | 2020 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.0045 | 0.068 |

| Euro V+ | 2024 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.0045 | 0.068 |

Emission standards for light commercial vehicles

[edit]

| Tier | Date (type approval) | Date (first registration) | CO | THC | NMHC | NOx | HC+NOx | PM | PN [#/km] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | |||||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 2.72 | – | – | – | 0.97 | 0.14 | – | ||

| Euro 2 | January 1997 | October 1997 | 1.0 | – | – | – | 0.7 | 0.08 | – | ||

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | January 2001 | 0.64 | – | – | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.05 | – | ||

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | January 2006 | 0.50 | – | – | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.025 | – | ||

| Euro 5a | September 2009 | January 2011 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.005 | – | ||

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6b | September 2014 | September 2015 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6c | – | September 2018 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2017 | September 2019 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6d | January 2020 | January 2021 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 0.500 | – | – | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 | ||

| Petrol | |||||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 2.72 | – | – | – | 0.97 | – | – | ||

| Euro 2 | January 1997 | October 1997 | 2.2 | – | – | – | 0.5 | – | – | ||

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | January 2001 | 2.3 | 0.20 | – | 0.15 | – | – | – | ||

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | January 2006 | 1.0 | 0.10 | – | 0.08 | – | – | – | ||

| Euro 5a | September 2009 | January 2011 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.005[a] | – | ||

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | – | ||

| Euro 6b | September 2014 | September 2015 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6c | – | September 2018 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2017 | September 2019 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6d | January 2020 | January 2021 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 | ||

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.060 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 | ||

| Tier | Date (type approval) | Date (first registration) | CO | THC | NMHC | NOx | HC+NOx | PM | PN [#/km] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | |||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 5.17 | – | – | – | 1.4 | 0.19 | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1998 | October 1998 | 1.25 | – | – | – | 1.0 | 0.12 | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2001 | January 2002 | 0.80 | – | – | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.07 | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2006 | January 2007 | 0.63 | – | – | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.04 | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2010 | January 2012 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.235 | 0.295 | 0.005 | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.235 | 0.295 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6b | September 2015 | September 2016 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2019 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2018 | September 2020 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d | January 2021 | January 2022 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 0.630 | – | – | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Petrol | |||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 5.17 | – | – | – | 1.4 | – | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1998 | October 1998 | 4.0 | – | – | – | 0.6 | – | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2001 | January 2002 | 4.17 | 0.25 | – | 0.18 | – | – | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2006 | January 2007 | 1.81 | 0.130 | – | 0.10 | – | – | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2010 | January 2012 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.005[a] | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | – |

| Euro 6b | September 2015 | September 2016 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2019 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2018 | September 2020 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d | January 2021 | January 2022 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 1.810 | 0.130 | 0.090 | 0.075 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Tier | Date (type approval) | Date (first registration) | CO | THC | NMHC | NOx | HC+NOx | PM | PN [#/km] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | |||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 6.9 | – | – | – | 1.7 | 0.25 | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1998 | October 1999 | 1.5 | – | – | – | 1.2 | 0.17 | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2001 | January 2002 | 0.95 | – | – | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.10 | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2006 | January 2007 | 0.74 | – | – | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.06 | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2010 | January 2012 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.280 | 0.350 | 0.005 | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.280 | 0.350 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6b | September 2015 | September 2016 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2019 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2018 | September 2020 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d | January 2021 | January 2022 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 0.740 | – | – | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.0045 | 6×1011 |

| Petrol | |||||||||

| Euro 1 | October 1993 | October 1994 | 6.9 | – | – | – | 1.7 | – | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1998 | October 1999 | 5.0 | – | – | – | 0.7 | – | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2001 | January 2002 | 5.22 | 0.29 | – | 0.21 | – | – | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2006 | January 2007 | 2.27 | 0.16 | – | 0.11 | – | – | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2010 | January 2012 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.005[a] | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | January 2013 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | – |

| Euro 6b | September 2015 | September 2016 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6c | – | September 2019 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d-Temp | September 2018 | September 2020 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6d | January 2021 | January 2021 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6e | September 2023 | September 2024 | 2.270 | 0.160 | 0.108 | 0.082 | – | 0.0045[a] | 6×1011 |

Emission standards for trucks and buses

[edit]

The emission standards for trucks (lorries) and buses are defined by engine energy output in g/kWh; this is unlike the emission standards for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, which are defined by vehicle driving distance in g/km — a general comparison to passenger cars is therefore not possible, as the kWh/km factor depends, among others, on the specific vehicle.

The official category name is heavy-duty diesel engines, which generally includes lorries and buses.

The following table contains a summary of the emission standards and their implementation dates. Dates in the tables refer to new type approvals; the dates for all new registrations are in most cases one year later.

| Tier | Date | Test cycle | CO | HC[a] | NOx | NH3[b] | PM | PN[c] [#/kWh] | N2O | CH4 | HCHO | Smoke [m−1] | Brake PM10[d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro I | 1992, < 85 kW |

ECE R49 |

4.5 | 1.1 | 8.0 | 0.612 | |||||||

| 1992, > 85 kW | 4.5 | 1.1 | 8.0 | 0.36 | |||||||||

| Euro II | October 1995 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 7.0 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| October 1997 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 7.0 | 0.15 | |||||||||

| Euro III | October 1999 EEVs[e] only |

ESC & ELR |

1.5 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.02 | 0.15 | ||||||

| October 2000 | 2.1 | 0.66 | 5.0 | 0.10 0.13[f] |

0.8 | ||||||||

| Euro IV | October 2005 | 1.5 | 0.46 | 3.5 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Euro V | October 2008 | 1.5 | 0.46 | 2.0 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Euro VI | 31 December 2012[34] | WHSC | 1.5 | 0.13 | 0.4 | 10 (ppm) | 0.01 | 8×1011 | |||||

| WHTC | 4.0 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 10 (ppm) | 0.01 | 6×1011 | |||||||

| |||||||||||||

Emission standards for large goods vehicles

[edit]| Standard | Date | CO | NOx | HC | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro 0 | 1988–92 | 12.3 | 15.8 | 2.6 | NA |

| Euro I | 1992–95 | 4.9 | 9.0 | 1.23 | 0.40 |

| Euro II | 1995–99 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 0.15 |

| Euro III | 1999–2005 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 0.66 | 0.1 |

| Euro IV | 2005–08 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 0.46 | 0.02 |

| Euro V | 2008–12 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.46 | 0.02 |

| Euro VI | 2012–19 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Standard | Date | CO | NOx | HC | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro 0 | 1988–92 | 11.2 | 14.4 | 2.4 | NA |

| Euro I | 1992–95 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 1.1 | 0.36 |

| Euro II | 1995–99 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 0.15 |

Emission standards for non-road mobile machinery

[edit]The term non-road mobile machinery (NRMM) is a term used in the European emission standards to control emissions of engines that are not used primarily on public roadways. This definition includes off-road vehicles as well as railway vehicles.

European standards for non-road diesel engines harmonise with the US EPA standards, and comprise gradually stringent tiers known as Stage I–V standards. The Stage I/II was part of the 1997 directive (Directive 97/68/EC). It was implemented in two stages, with Stage I implemented in 1999 and Stage II implemented between 2001 and 2004. In 2004, the European Parliament adopted Stage III/IV standards. The Stage III standards were further divided into Stage III A and III B, and were phased in between 2006 and 2013. Stage IV standards are enforced from 2014. Stage V standards are phased in from 2018 with full enforcement from 2021.

As of 1 January 2015, EU Member States have to ensure that ships in the Baltic, the North Sea and the English Channel are using fuels with a sulphur content of no more than 0.10%. Higher sulphur contents are still possible, but only if the appropriate exhaust cleaning systems are in place.[35]

Emission test cycle

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2020) |

Just as important as the regulations are the tests needed to ensure adherence to regulations. These are laid out in standardised emission test cycles used to measure emissions performance against the regulatory thresholds applicable to the tested vehicle.

Light duty vehicles

[edit]Since the Euro 3 regulations in 2000, performance has been measured using the New European Driving Cycle test (NEDC; also known as MVEG-B), with a "cold start" procedure that eliminates the use of a 40-second engine warm-up period found in the ECE+EUDC test cycle (also known as MVEG-A).[27][36] Since 2017 the NEDC was replaced by the Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP).[37]

Heavy duty vehicles

[edit]The two groups of emissions standards for heavy duty vehicles each have different appropriate test requirements. Steady-state testing is used for diesel engines only, while transient testing applies to both diesel and petrol engines.[38]

"Cycle beating" controversy

[edit]

For the emission standards to deliver actual emission reductions, it is crucial to use a test cycle that reflects real-world driving conditions. It was discovered[40] that vehicle manufacturers would optimise emissions performance only for the test cycle, whilst emissions from typical driving conditions proved to be much higher than when tested. Some manufacturers were also found to use so-called defeat devices where the engine control system would recognise that the vehicle was being tested, and would automatically switch to a mode optimised for emissions performance. The use of a defeat device is expressly forbidden in EU law.[28]

An independent study in 2014 used portable emissions measurement systems to measure NOx emissions during real world driving from fifteen Euro 6 compliant diesel passenger cars. The results showed that NOx emissions were on average about seven times higher than the Euro 6 limit. However, some of the vehicles did show reduced emissions, suggesting that real world NOx emission control is possible.[41] In one particular instance, research in diesel car emissions by two German technology institutes found that zero "real" NOx reductions in public health risk had been achieved despite 13 years of stricter standards (2006 report).[42]

In 2015, the Volkswagen emissions scandal involved revelations that Volkswagen AG had deliberately falsified emission reports by programming engine management unit firmware to detect test conditions, and change emissions controls when under test. The cars thus passed the test, but in real world conditions, emitted up to forty times more NOx emissions than allowed by law.[43] An independent report in September 2015 warned that this extended to "every major car manufacturer",[44] with BMW, and Opel named alongside Volkswagen and its sister company Audi as "the worst culprits",[44] and that approximately 90% of diesel cars "breach emissions regulations".[44] Overlooking the direct responsibility of the companies involved, the authors blamed the violations on a number of factors, including "unrealistic test conditions, a lack of transparency and a number of loopholes in testing protocols".[44]

In 2017, the European Union introduced testing in real-world conditions called Real Driving Emissions (RDE), using portable emissions measurement systems in addition to laboratory tests.[45] The actual limits will use 110% (CF=2.1) "conformity factor" (the difference between the laboratory test and real-world conditions) in 2017, and 50% (CF=1.5) in 2021 for NOx,[46] conformity factor for particles number P being left for further study. Environment organisations criticized the decision as insufficient,[47][48] while ACEA mentions it will be extremely difficult for automobile manufacturers to reach such a limit in such short period of time.[49] In 2015, an ADAC study (ordered by ICCT) of 32 Euro 6 cars showed that few complied with on-road emission limits, and LNT/NOx adsorber cars (with about half the market) had the highest emissions.[50] At the end of this study, ICCT was expecting a 100% conformity factor.[51]

NEDC Euro 6b not to exceed limit of 80 mg/km NOx will then continue to apply for the WLTC Euro 6c tests performed on a dynomometer while WLTC-RDE will be performed in the middle of the traffic with a PEMS attached at the rear of the car. RDE testing is then far more difficult than the dynomometer tests. RDE not to exceed limits have then been updated to take into account different test conditions such as PEMS weight (305–533 kg in various ICCT testing[52]), driving in the middle of the traffic, road gradient, etc.

ADAC also performed NOx emission tests with a cycle representative of the real driving environment in the laboratory.[53][54] Among the 69 cars tested:

- 17 cars emit less than 80 mg/km, i.e. do not emit more NOx on this more demanding cycle than on the NEDC cycle.

- 22 additional cars fall below the 110% conformity factor. In total: 57% of cars have then a good chance to be compatible with WLTC-RDE.

- 30 cars fall above the 110% conformity factor and have then to be improved to satisfy the WLTC-RDE test.

Since 2012, ADAC performs regular pollutant emission tests[55][56] on a specific cycle in the laboratory duly representing a real driving environment and gives a global notation independent from the type of engine used (petrol, diesel, natural gas, LPG, hybrid, etc.). To get the maximum 50/50 note on this cycle, the car shall emit less than the minimum limit applicable to either petrol or diesel car, that is to say 100 mg HC, 500 mg CO, 60 mg NOx, 3 mg PM and 6×1010 PN. Unlike ambient discourse dirty diesel versus clean petrol cars, the results are much more nuanced and subtle. Some Euro 6 diesel cars perform as well as the best hybrid petrol cars; some other recent Euro 6 petrol indirect injection cars perform as the worst Euro 5 diesel cars; finally some petrol hybrid cars are at the same level as the best Euro 5 diesel cars.[57][58]

Tests commissioned by Which? from the beginning of 2017 found that 47 out of 61 diesel car models exceed the Euro 6 limit for NOx, although they conform to official standards.[59]

Health impacts

[edit]After the postponement in publishing the Euro 7 proposal details by the European Commission, some civil society groups (such as the European Respiratory Society and the European Public Health Alliance) said in mid-2022: "Every month that the implementation of Euro 7 is delayed due to the late publication of the proposal, 1 million more polluting cars will be placed on the EU's road and stay there for decades to come."[60]

CO2 emissions

[edit]Within the European Union, transport is the biggest emitter of CO2,[61] with road transport contributing about 20%.[62]

Obligatory labelling

[edit]The purpose of Directive 1999/94/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 13 December 1999 relating to the availability of consumer information on fuel economy and CO2 emissions in respect of the marketing of new passenger cars[63] is to ensure that information relating to the fuel economy and CO2 emissions of new passenger cars offered for sale or lease in the Community is made available to consumers in order to enable consumers to make an informed choice.

In the United Kingdom, the initial approach was deemed ineffective. The way the information was presented was too complicated for consumers to understand. As a result, car manufacturers in the United Kingdom voluntarily agreed to put a more "consumer-friendly", colour-coded label displaying CO2 emissions on all new cars beginning in September 2005, with a letter from A (<100 CO2 g/km) to F (186+ CO2 g/km). The goal of the new "green label" is to give consumers clear information about the environmental performance of different vehicles.[64]

Other EU member countries are also in the process of introducing consumer-friendly labels.

Obligatory vehicle CO2 emission limits

[edit]European Union Directive No 443/2009 set a mandatory average fleet CO2 emissions target for new cars, after a voluntary commitment made in 1998 and 1999 by the auto industry had failed to reduce emissions by 2007. The regulation applies to new passenger cars registered in the European Union and EEA member states for the first time. A carmaker who fails to comply has to pay an "excess emissions premium" for each vehicle registered according with the amount of g/km of exceeded.[65]

Source: Norwegian Road Federation (OFV)

The 2009 regulation set a 2015 target of 130 g/km for the fleet average for new passenger cars. A similar set of regulations for light commercial vehicles was set in 2011, with an emissions target of 175 g/km for 2017. Both targets were met several years in advance. A second set of regulations, passed in 2014, set a 2021 target of average CO2 emissions of new cars to fall to 95 g/km by 2021, and for light-commercial vehicles to 147 g/km by 2020.[66][67]

In April 2019, Regulation (EU) 2019/631 was adopted, which introduced CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars and new light commercial vehicles for 2025 and 2030. The new Regulation went into force on 1 January 2020, and has replaced and repealed Regulation (EC) 443/2009 and (EU) No 510/2011.[66][68] The 2019 Regulation set new emission targets relative to a 2021 baseline, with a reduction of the average CO2 emissions from new cars by 15% in 2025, and by 37.5% in 2030. For light-commercial vehicles the new targets are a 15% reduction for 2025 and a 31% reduction for 2030.[67][69]

Specific emissions targets for passenger cars

To account for different sizes of passenger cars, the specific emissions target for each passenger car is calculated by adjusting the general emissions target by a value proportional to the deviation of the car's mass from the average. This means that the emissions targets for heavier cars are higher than those for lighter cars. In Regulations (EC) 443/2009 and (EU) 2019/631 this relationship between the specific emissions target E and the general emissions target E0 is expressed as E = E0 + a × (M-M0) with the mass of the specific vehicle denoted by M and the average vehicle mass denoted by M0 (approx. 1,400 kg (3,100 lb)). The Regulations determine the factor a as 0.0457 for 2012–2019 and as 0.0333 from 2020 onward.[65][68]

Pooling

Two or more car manufacturers may form a pool which allows them to meet fleet targets as a group instead of having to meet them individually. The first pool was agreed among Tesla and Fiat Chrysler in 2019, reportedly costing Fiat Chrysler hundreds of millions of Euros.[70]

ZLEV Credit System

The 2019 Regulation also introduced an incentive mechanism or credit system from 2025 onwards for zero- and low-emission vehicles (ZLEVs). A ZLEV is defined as a passenger car or a commercial van with CO2 emissions between 0 and 50 g/km. The regulation set ZLEV sales targets of 15% for 2025 and 35% for 2030, and manufacturers have some flexibility in how they achieve those targets. Carmakers that outperform the ZLEV sales targets will be rewarded with higher CO2 emission targets, but the target relaxation is capped at a maximum 5% to safeguard the integrity of the regulation.[67][69]

Electrification

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

Many EU member states have responded to this problem by exploring the possibility of including electric vehicle-related infrastructure into their existing road traffic system, with some even having begun implementation. The UK has begun its "plugged-in-places" scheme which sees funding go to several areas across the UK to create a network of charging points for electric vehicles.[71]

Around the world

[edit]- Since 1 January 2012, all new heavy vehicles in Brazil must comply with Proconve P7 (similar to Euro 5)[72]

- Since September 2014, all new cars in Chile must comply with Euro 5.[73]

- Since 1 January 2015, all new light vehicles in Brazil must comply with Proconve L6 (similar to Euro 5).[74]

- Since 1 January 2016, all new heavy vehicles in Argentina must comply with Euro 5.[75]

- Since January 2016, all new light vehicles in Russia must comply with Euro 5.[76]

- Since 2016, all new vehicles in Turkey must comply with Euro 6.[77][78]

- Since 1 September 2017, all new petrol vehicles in Singapore must comply with Euro 6 with new diesel vehicles following suit from 1 January 2018.[79][80]

- Since 1 January 2018, all new vehicles in the Philippines must comply with Euro 4.

- Since 1 January 2018, all new vehicles in China must comply with China 5 (similar to Euro 5).[81]

- Since 1 January 2018, all new light and heavy vehicles in Argentina must comply with Euro 5.[82]

- Since 2018, all new heavy vehicles in Russia must comply with Euro 5.[76]

- Since 1 April 2018, Euro 4, Tier 2, and EPA 2007 are mandated in Peru.[83]

- Since 8 October 2018, all new petrol cars in Indonesia must comply with Euro 4.[84]

- Since 1 July 2019, all new heavy vehicles in Mexico must comply with EPA 07 and Euro 5.[85]

- Since 1 April 2020, all new 2, 3 or 4-wheelers in India must comply with BS VI (similar to Euro 6)[86]

- Since 1 January 2021, all new vehicles in ECOWAS must comply with Euro 4.[87]

- Since 1 January 2021, all new vehicles in China must comply with China 6a (similar to Euro 6).[88]

- Since 1 January 2022, all new vehicles in Cambodia must comply with Euro 4.[89]

- Since 1 January 2022, all new cars in Vietnam must comply with Euro 5.[90]

- Since 1 January 2022, all new light vehicles in Brazil must comply with Proconve L7 (similar to Euro 6).[91]

- Since September 2022, all new light and medium vehicle models in Chile must comply with Euro 6b.[92]

- Since 12 April 2022, all new diesel vehicles in Indonesia must comply with Euro 4.[93]

- Since 1 January 2023, all new heavy vehicles in Brazil must comply with Proconve P8 (similar to Euro 6).[94]

- Since 1 January 2023, all new vehicles in Colombia must comply with Euro 6b.[95][96]

- Since 1 July 2023, all new vehicles in China must comply with China 6b (more strict than provisional so-called "Euro 7").[88]

- Since 1 January 2024, all new vehicles in Thailand must comply with Euro 5.[97]

- Since 1 January 2024, all new vehicles in Morocco must comply with Euro 6b.[98]

- Since 1 October 2024, Euro 6b, Tier 3, and EPA 2010 are mandated in Peru for new vehicles.[99]

- Since 1 January 2025, all new heavy vehicles in Mexico must comply with EPA 10 and Euro 6.[85]

- Since 1 January 2025, the new light vehicle fleets in Brazil must comply with the first stage of Proconve L8 (automaker average).[100]

- From 30 September 2025, all new light and medium vehicle models in Chile must comply with Euro 6c.[101]

- From December 2025, all new vehicles sold in Australia must comply with Euro 6d.[102]

- From 1 January 2027, all new vehicles in Cambodia must comply with Euro 5.[89]

Bans

[edit]Full-time car bans

[edit]- Euro 0 petrol or diesel – With exceptions, parts of: Neu-Ulm and 42 other towns of Germany.[103]

- Euro 1 petrol or diesel – Ghent[104] With exceptions, parts of: Antwerp, Brussels

- Euro 1 gas[a] – 76 towns of Piedmont[105]

- Euro 2 diesel – Parts of: Neu-Ulm[103]

- Euro 2 petrol or diesel – 76 towns of Piedmont[105]

- Euro 2 – Madrid (nonlocal)[106] With exceptions, parts of: Torrejón de Ardoz and Zaragoza.[107][108]

- Euro 3 diesel – Amsterdam, Arnhem, The Hague, Utrecht, Madrid (nonlocal), and parts of 42 towns of Germany.[104][106][103] With exceptions, parts of: Grand Lyon, Aix-Marseille-Provence Metropolis, Rouen, Strasbourg, Toulouse, Torrejón de Ardoz and Zaragoza.[109][107][108] With exceptions and free public transport, parts of: Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole[110][111][112]

- Euro 3 petrol or diesel – With exceptions, retrofit funding, and replacement-neutral scrappage, parts of: Glasgow[113][114][115]

- Euro 3 petrol - Since 1 October 2024, in Milan's inner ZTL (Area C), all petrol-engine passenger cars are required to be Euro 4 or a higher class.[116]

- Euro 4 diesel – Ghent, Munich, and Stuttgart.[104][117] With exceptions, parts of: Antwerp, Brussels, Madrid[118]

- Euro 4 petrol - Since 1 October 2027, in Milan's inner ZTL (Area C), all petrol-engine passenger cars are required to be Euro 5 or a higher class.[116]

- Euro 5 diesel – Darmstadt and parts of Stuttgart[117] With exceptions, parts of: Aalborg, Aarhus, Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, and Odense[119] With exceptions, retrofit funding, and replacement-neutral scrappage, parts of: Glasgow[113][114][115]

- Euro 5 petrol - Since 1 October 2030, in Milan's inner ZTL (Area C), all petrol-engine passenger cars are required to be Euro 6 or a higher class.[116]

- Euro 6 non-gas[b] or non-electrified[c] – With exceptions, center of: Madrid[120][121]

- Since 2019, some German cities ban Euro 4 or 5 diesel cars.[122]

- Since 1 September 2022, Euro 3 diesel cars are banned in Rouen and Toulouse (with exceptions).[109]

- Since 1 June 2023, Euro 3 (petrol or diesel) cars and Euro 5 diesel cars are banned (with exceptions, retrofit funding, and replacement-neutral scrappage) in parts of: Glasgow.[113][114][115]

- Since September 2023, Euro 3 diesel cars are banned in parts of Aix-Marseille-Provence Metropolis (with exceptions).[109]

- Since 1 October 2023, Euro 5 diesel cars are banned (with exceptions) in parts of: Aalborg, Aarhus, Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, and Odense.[119]

- Since 1 January 2024, Euro 2 cars and Euro 3 diesel cars are banned (with exceptions) in parts of: Torrejón de Ardoz and Zaragoza[107][108]

- Since 1 January 2024, Euro 3 diesel cars are banned in Grand Lyon (with exceptions) and parts of Strasbourg.[109] With exceptions and free public transport, in parts of: Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole.[110][111][112]

- Since 1 January 2024, Euro 6 non-gas[b] or non-electrified[c] cars are banned (with exceptions) in the center of: Madrid[120][121]

- Since 30 May 2024, Euro 3 (petrol or diesel) cars and Euro 5 diesel cars are banned (with exceptions, retrofit funding, and replacement-neutral scrappage) in parts of: Dundee.[114][115]

- Since 1 June 2024, Euro 3 (petrol or diesel) cars and Euro 5 diesel cars are banned (with exceptions, retrofit funding, and replacement-neutral scrappage) in parts of: Aberdeen and Edinburgh.[114][115]

- Since 1 January 2025, Euro 1 cars will be banned in Nantes.[123]

- Since 1 January 2025, Euro 2 cars and Euro 3 diesel cars will be banned in Madrid (with exceptions).[106]

- Since 1 January 2025, Euro 3 (petrol or diesel) cars and Euro 4 diesel cars will be banned in parts of Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole (with exceptions and free public transport) and Grand Paris.[111][112][124]

- From 1 April 2025, Euro 2 cars and Euro 3 diesel cars will be banned in Granada (nonlocal).[125]

- From 1 January 2028, Euro 4 (petrol or diesel) cars and Euro 6 diesel cars will be banned in parts of: Grand Lyon.[126]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gas here refers to natural gas or LPG

- ^ a b Gas here refers to natural gas, LPG, or HICEV. It is not guaranteed that bi-fuel vehicles will be running on gas.

- ^ a b Electrified here includes mild hybrids, even if many pollute more than some banned cars. Also, a PHEV with a depleted battery is worse than a full hybrid or series hybrid version.

See also

[edit]- ACEA agreement (the voluntary agreement with auto manufacturers to limit CO2 emissions)

- AIR Index (a motor vehicle emissions ranking system)

- Air quality and EU legislation

- Biofuels Directive

- Vehicle emission standards

- EN 590

- Energy policy of the European Union

- European Common Transport Policy

- European Federation for Transport and Environment

- European Union Emission Trading Scheme

- Life cycle assessment

- Low-emission zone

- Motor vehicle emissions

- National Emission Ceiling

- Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles

- Portable emissions measurement system

- Regulation on non-exhaust emissions

- Type approval

- Ultra-low-sulfur diesel

- United States vehicle emission standards

- World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE))

References

[edit]- ^ "What are the Euro Emissions Standards?". Stratstone. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Euro 6 Guide to Emission Standards (2022 Update) | Motorway (2022)". Unbate. 28 April 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Lampinen, Megan (2 August 2024). "Lowering the limit: Euro 7 brake emissions update". Automotive World. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "Should Tire And Brake Emissions Be Regulated?". 17 July 2024.

- ^ DELLI, Karima. "Parliamentary question | Euro 7 – non-exhaust particulate emissions | E-002194/2021 | European Parliament". European Parliament. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "Parliamentary question | Answer for question E-002194/21 | E-002194/2021(ASW) | European Parliament". European Parliament. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ de Prez, Matt (19 December 2023). "EU strikes provisional deal over Euro 7 emissions limits". Fleet News. UK. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Euro 7: Council adopts new rules on emission limits for cars, vans and trucks - Consilium".

- ^ "Euro 7: The new emission standard for light- and heavy-duty vehicles in the European Union".

- ^ European Parliament (November 2023). "Euro 7 motor vehicle emission standards" (PDF).

- ^ "EU: Heavy-duty: Emissions | Transport Policy". www.transportpolicy.net. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "NEDC: How do lab tests for cars work?". Car Emissions Testing Facts. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "What are the Euro 7 emissions standards?". Auto Express. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "European Commission > Enterprise and Industry > Sectors > Automotive > Reference documents > Directives and regulations > Directive 70/220/EEC". European Commission. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "91/441/EEC Council Directive 91/441/EEC of 26 June 1991 amending Directive 70/220/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to measures to be taken against air pollution by emissions from motor vehicles". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 26 June 1991. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Directive 2002/51/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 July 2002 on the reduction of the level of pollutant emissions from two- and three-wheel motor vehicles and amending Directive 97/24/EC". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 19 July 2002. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Directive 98/69/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 1998 relating to measures to be taken against air pollution by emissions from motor vehicles and amending Council Directive 70/220/EEC". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 13 October 1998. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2007 on type approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on access to vehicle repair and maintenance information". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Commission Regulation (EU) No 459/2012 of 29 May 2012 amending Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as regards emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 6)". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/646 of 20 April 2016 amending Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as regards emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 6)". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ "EU Parliament approves compromise on vehicle pollution limits". Reuters.

- ^ Timmler, Vivien (7 April 2024). "Verbrenner-Aus: Wagenknecht fordert "neue Verbrennergeneration"". Süddeutsche.de.

- ^ "EUROPA > Summaries of EU legislation > Internal market > Single Market for Goods > Motor vehicles > Technical harmonisation for motor vehicles". Europa (web portal). 29 October 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Council Directive 70/156/EEC of 6 February 1970 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the type-approval of motor vehicles and their trailers". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Commission Directive 2001/116/EC of 20 December 2001 adapting to technical progress Council Directive 70/156/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the type-approval of motor vehicles and their trailers". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 20 December 2001. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Macaudière, Pierre; Matthess, Nils (January 2013). "Élimination des particules" (PDF) (Press release). PSA Peugeot Citroen. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Emission Standards » European Union » Cars and Light Trucks". DieselNet. January 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Regulation (EC) No 715/2007". The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 20 June 2007. pp. 5–9. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "Volkswagen Test Rigging Follows a Long Auto Industry Pattern". The New York Times. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "Euro 5 motorcycles, Euro 5 emissions legislation could mean the disappearance of two-stroke engines". INFINEUM INTERNATIONAL LIMITED. 14 August 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "HISTORY OF MOTORCYCLE EMISSIONS STANDARDS". AECC (the Association for Emissions Control by Catalyst). 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Study on possible new measures concerning motorcycle emissions" (PDF). The Laboratory of Applied Thermodynamics Department of Mechanical Engineering Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. 1 September 2009. pp. 44–45. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON CLEAN TRANSPORTATION. "Emissions performance of Euro VI-D buses and recommendations for Euro 7 standards" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 582/2011 (Euro VI), date is for type approvals, ANNEX I, Euro VI Emission Limits". p. 167/163. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Transport & Environment – Emissions from Maritime Transport". European Commission. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Emission Test Cycles: ECE 15 + EUDC / NEDC". DieselNet. July 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Kroher, Thomas (5 March 2024). "WLTP statt NEFZ: So funktioniert das aktuelle Messverfahren". ADAC, Allemeiner Deutscher Automobil Club. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Emission Standards » European Union » Heavy-Duty Truck and Bus Engines". DieselNet. September 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Comparison of NOx emission standards for different Euro classes". European Environment Agency. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Don't Breathe Here: Tackling air pollution from vehicles". Transport Environment. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Real-world exhaust emissions from modern diesel cars". International Council on Clean Transportation. 11 October 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "WHO adds pressure for stricter Euro-5 standards" (PDF). Transport Environment.org Transport & Environment, Bulletin. No. 146. European Federation for Transport and Environment. March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Ewing, Jack; Davenport, Coral (20 September 2015). "Volkswagen to Stop Sales of Diesel Cars Involved in Recall". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Kirk, Ashley (22 September 2015). "Volkswagen emissions scandal: Which other cars fail to meet pollution safety limits?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Real Driving Emissions 2015". Real Driving Emissions. 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "European Commission welcomes Member States' agreement on robust testing of air pollution emissions by cars" (Press release). European Commission. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Bennett, Jon (28 October 2015). "Diesel: Shocking new rules would allow twice the pollution [3026]". ClientEarth. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Governments double and delay air pollution limits for diesel cars". transportenvironment.org. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Auto industry reacts to new real driving emissions testing standards". 30 October 2015.

- ^ Yang, Liuhanzi; Franco, Vicente; Campestrini, Alex; German, John; Mock, Peter (3 September 2015). "NOx control technologies for Euro 6 diesel passenger cars". The International Council on Clean Transportation. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "ICCT expected conformity factor" (PDF). September 2015. p. 20 (PDF page 27).

- ^ "PEMS Weight" (PDF). p. 11 (PDF page 27, table 3.2).

- ^ "ADAC NOx Tests concerning 69 Euro 6 Diesel cars" (PDF).

- ^ "ADAC NOX tests on 69 Euro 6 Diesel cars shown in pictures by AutoBild". Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "English version of ADAC pollutant tests procedure" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Original ADAC Emissions Tests procedure" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2015.

- ^ "English version of ADAC Emissions tests concerning Euro 5 & Euro 6 cars".

- ^ "Original ADAC emissions tests concerning Euro 5 & Euro 6 cars" (in German).

- ^ "Most modern diesels still too dirty, study shows". UK: Sky News. 17 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ "'Publish the Euro 7 air quality standards without delay'". Transport & Environment. 1 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "EU-27: CO2 emissions shares by sector 2019". Statista. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Road transport: Reducing CO₂ emissions from vehicles". European Commission. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Directive 1999/94/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 1999 relating to the availability of consumer information on fuel economy and CO2 emissions in respect of the marketing of new passenger cars". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 13 December 1999. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Resources for the Future, Resources Magazine, Weathervane, One Car At A Time". Rff.org. 10 January 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Regulation (EC) No 443/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council". Official Journal of the European Union. 23 April 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Reducing CO2 emissions from passenger cars – before 2020". European Commission. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b c International Council on Clean Transportation (January 2019). "CO2 standards for passenger cars and light-commercial vehicles in the European Union" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Regulation (EU) 2019/631 of the European Parliament and of the Council". Official Journal of the European Union. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b "CO2 emission performance standards for cars and vans (2020 onward)". European Commission. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Fiat Chrysler to pay Tesla hundreds of millions of euros to pool fleet". Reuters. 7 April 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Recharging infrastructure". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Indústria pronta para Euro 5 em 2012 – Diário do Grande ABC – Notícias e informações do Grande ABC: economia". Dgabc.com.br. 26 March 2011.

- ^ O, Catalina Rojas (4 February 2013). "Euro 5: la norma de emisiones para vehículos que empieza este año y que posiciona a Chile como líder en Latinoamérica". La Tercera.

- ^ Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis (29 November 2011). "Programa de Controle da Poluição do Ar por Veículos Automotores" [Air Pollution Control Program for Motor Vehicles] (PDF). Brazil. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Panzera, Daniel (1 September 2015). "En el 2016 entrará en vigor la norma Euro V para camiones y transporte de pasajeros". 16 Valvulas.

- ^ a b "Emission Standards: Russia and EAEU". dieselnet.com.

- ^ "Left in the dust: Brazil might be the last major automotive market to adopt Euro VI standards". International Council on Clean Transportation. 23 May 2018.

- ^ "THE AUTOMOTIVE SECTOR IN TURKEY A BASELINE ANALYSIS OF VEHICLE FLEET STRUCTURE, FUEL CONSUMPTION AND EMISSIONS" (PDF). International Council on Clean Transportation. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Singapore Will Adopt the Euro VI Emission Standards for Petrol Vehicles from September 2017". www.nea.gov.sg. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Singapore Will Usher In Euro VI Emission Standard For Diesel Vehicles From January 2018". www.nea.gov.sg. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Early adoption of China 5/V vehicle emission standards in Guangdong province" (PDF). The International Council on Clean Transportation. May 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "DPF: la sigla que se convirtió en un dolor de cabeza para automotrices y usuarios argentinos". Motor1.com.

- ^ "Peru adopts Euro 4 / IV vehicle emissions standards for improved air quality". UN Environment Programme. 18 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Mongabay (26 November 2020). "Standard Emisi Kendaraan di Indonesia, Sejauh Apa Penerapannya?" [Vehicle Emission Standards in Indonesia, How Far is It Implemented?]. Indonesia. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Semarnat publica en el DOF modificación a la NOM-044". t21.com.mx.

- ^ "Amid lockdown, India switches to BS-VI emission norms". The Hindu. 1 April 2020.

- ^ "West African Ministers adopt cleaner fuels and vehicles standards". UNEP. 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Emission Standards: China: Cars and Light Trucks". dieselnet.com.

- ^ a b "Cambodia In The Driver's Seat Toward Euro VI Standards | Climate & Clean Air Coalition". www.ccacoalition.org.

- ^ "Euro 5 emission standards to be rolled out for new cars in Vietnam early 2022 | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Nova lei de emissões vai tirar de linha 6 carros e 4 motores até o fim do ano; veja lista". Autoesporte.globo.com. 3 December 2021.

- ^ "Chile avanza hacia la norma de emisiones Euro 6b". Autocosmos. 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Mobil Diesel di Indonesia Wajib Euro 4 Mulai 12 April 2022" [Diesel Cars in Indonesia Must Euro 4 Starting April 12, 2022]. Indonesia. 8 April 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Novos limites de emissões vão aquecer venda de implementos rodoviários". O Estado de S. Paulo. 11 February 2022.

- ^ "¿El transporte en Colombia está listo para la Euro VI?" [Is transportation in Colombia ready for Euro VI?]. Semana.com Últimas Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo (in Spanish). Colombia. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Ley 1972 de 2019 – por medio de la cual se establece la protección de los derechos a la salud y al medio ambiente sano estableciendo medidas tendientes a la reducción de emisiones contaminantes de fuentes móviles y se dictan otras disposiciones" [Law 1972 of 2019 – through which the protection of the rights to health and a healthy environment is established establishing measures to reduce polluting emissions from mobile sources and other provisions are issued] (in Spanish). Colombia: Ministry of Environment, Housing and Territorial Development. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Thailand approves delay on imposing Euro 5 emission standard on new vehicles". Pattaya Mail. 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Norme antipollution. Le Maroc passe officiellement au carburant Euro 6 dès 2022 | Challenge.ma". challenge.ma. 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Decreto supremo que modifica el Decreto supremo n° 010-2017-MINAM, que establece límites máximos permisibles de emisiones atmosféricas para vehículos automotores" [Maximum permissible limits of atmospheric emissions for motor vehicles] (in Spanish). Peru. 2021. 2021-MINAM. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "MINISTÉRIO DO MEIO AMBIENTE CONSELHO NACIONAL DO MEIO AMBIENTE RESOLUÇÃO N. 492, DE 20 DE DEZEMBRO DE 2018". Conama.mma.gov.br. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "ANAC aclara que norma de emisiones Euro 6c comenzará a regir desde el 30 de septiembre de 2025 – Anac".

- ^ "Strict new-car emissions standards coming to Australia from 2025, utes and 4WDs among hardest hit". Drive. 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Umweltzonen, Durchfahrtsbeschränkungen und Luftreinhaltepläne". gis.uba.de.

- ^ a b c "Fahrverbote und Umweltzonen im Ausland". www.adac.de. 9 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Migliorare la qualità dell'aria: le misure strutturali e temporanee per la circolazione dei veicoli". Regione Piemonte.

- ^ a b c Otero, Alejandra (1 December 2023). "En un mes los coches sin etiqueta no podrán circular por Madrid. Estas son todas las excepciones". Motorpasión.

- ^ a b c "Mapa ZBE Torrejón de Ardoz | RACE".

- ^ a b c "Todas las restricciones de las Zonas de Bajas Emisiones (ZBE) en 2024". 15 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Zones à faibles émissions : interdiction des véhicules Crit'Air 3, 4 ou 5 ? Ville par ville, ce qui change en 2024". TF1 INFO. 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Dérogations, amendes : avec la ZFE, qu'est-ce qui change pour les voitures Crit'Air 4 à Montpellier et dans la Métropole ?". midilibre.fr.

- ^ a b c "ZFE à Montpellier : les motos autorisées sans vignette Crit'Air, les véhicules circulant moins de 52 jours par an n'ont plus aucune interdiction". France 3 Occitanie. 24 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "VIDEO. A Montpellier, les transports rendus gratuits pour tous les habitants". Franceinfo. 12 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Gareth. "Older vehicles banned from Glasgow as low emission zone launches". www.fleetnews.co.uk.

- ^ a b c d e "Low emission zone retrofit fund". Energy Saving Trust.

- ^ a b c d e "Mobility and scrappage fund". Energy Saving Trust.

- ^ a b c "Area C: prohibition calendar". City of Milan. 11 July 2024. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Dieselfahrverbot". www.adac.de. 27 September 2023.

- ^ Sirvent, Gustavo López (2 October 2023). "Todas las ciudades donde no podrán entrar los coches con etiqueta B en enero". Top Gear España.

- ^ a b "Where are the zones?". miljoezoner.dk.

- ^ a b López, Noelia (26 December 2023). "La guía que necesitas para conducir en Madrid 2024, según la pegatina de la DGT que tenga tu coche". Auto Bild España.

- ^ a b Murias, Daniel (3 November 2023). "La OCU vuelve a pedir un cambio en las etiquetas de la DGT, pero solo ven una parte del problema". Motorpasión.

- ^ "German cities can ban Euro 5 diesels immediately". Fleet Europe. 21 May 2018.

- ^ AMIOTTE, Sylvain (16 December 2023). "Zone à faibles émissions : le choix d'une restriction minimaliste à Nantes". Ouest-France.fr.

- ^ "ZFE : nouveau répit avant l'interdiction des Crit'Air 3 dans le Grand Paris". TF1 INFO. 13 July 2023.

- ^ "La zona de bajas emisiones abarcará todo el perímetro de Granada capital limitado por la circunvalación". Europa Press. 31 January 2024.

- ^ "ZFE à Lyon: l'interdiction des véhicules Crit'Air 2 reportée "au 1er janvier 2028"" – via www.bfmtv.com.

External links

[edit]European emission standards

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins and Early Implementation (Euro 1 to Euro 3)

The European emission standards for motor vehicles emerged in response to rising concerns over urban air pollution from exhaust gases, prompting the European Economic Community (EEC) to harmonize member states' regulations. The foundational framework was established by Council Directive 70/220/EEC of 20 March 1970, which focused on approximating laws relating to measures against air pollution by emissions from positive-ignition (petrol) engines in passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, setting initial limits for carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbons (HC) tested under steady-state conditions.[8] This directive, later amended extensively, laid the groundwork for type-approval procedures but imposed relatively lenient limits compared to contemporaneous U.S. standards, reflecting Europe's slower initial regulatory response to vehicle emissions amid priorities for economic integration and fuel efficiency.[2] Separate provisions for diesel engines followed with Directive 72/306/EEC in 1972, targeting particulate matter (PM), though enforcement emphasized lab-based testing over real-world performance.[3] The "Euro" nomenclature began with Euro 1 standards in 1992, marking the first binding EU-wide limits for both petrol and diesel light-duty vehicles (passenger cars under 2.5 tonnes and light trucks), implemented via Directive 91/441/EEC for cars and 93/59/EEC for light commercials. These applied to CO, HC, nitrogen oxides (NOx), and PM (diesel only), measured over the ECE urban driving cycle plus extra-urban EUDC, with limits in g/km. Euro 1 required type approval from July 1992 for new models, extending to all new vehicles by early 1993, but allowed higher tolerances for cold-start emissions and did not mandate catalytic converters universally, limiting effectiveness against NOx from diesels.[2]| Pollutant | Petrol (Positive Ignition) | Diesel |

|---|---|---|

| CO (g/km) | 2.72 | 2.72 |

| HC (g/km) | - | - |

| HC+NOx (g/km) | 0.97 | - |

| NOx (g/km) | - | - |

| PM (g/km) | - | 0.14 |

| Pollutant | Petrol | Diesel (IDI) | Diesel (DI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO (g/km) | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| HC (g/km) | 0.5 | - | - |

| HC+NOx (g/km) | - | - | - |

| NOx (g/km) | - | - | - |

| PM (g/km) | - | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Pollutant | Petrol | Diesel |

|---|---|---|

| CO (g/km) | 2.3 | 0.64 |

| HC (g/km) | 0.2 | - |

| HC+NOx (g/km) | - | 0.56 |

| NOx (g/km) | - | 0.50 |

| PM (g/km) | - | 0.050 |

Evolution to Euro 4 through Euro 6

Euro 4 standards, introduced via Directive 2005/55/EC for heavy-duty engines and amendments to Directive 70/220/EEC for light-duty vehicles, took effect for new light-duty vehicle types in January 2005 and all new registrations by January 2006, while heavy-duty Euro IV applied from October 2005 for engines and January 2006 for vehicles.[2][3] These standards halved NOx limits for diesel light-duty passenger cars to 0.25 g/km from Euro 3 levels and reduced particulate matter (PM) to 0.025 g/km, with CO limited to 0.5 g/km; for petrol vehicles, CO was capped at 1.0 g/km and combined HC+NOx at 0.08 g/km.[2] Heavy-duty Euro IV set NOx at 3.5 g/kWh and PM at 0.02 g/kWh, reflecting advances in exhaust aftertreatment like diesel particulate filters (DPFs) becoming more widespread, though real-world emissions often exceeded lab-tested limits due to test cycle limitations.[3][9] Euro 5 standards, established under Regulation (EC) No 715/2007, applied to new light-duty types from September 2009 and all vehicles from January 2011, introducing fuel-neutral PM limits for direct-injection petrol engines and further tightening diesel NOx to 0.18 g/km and PM to 0.005 g/km while maintaining CO at 0.5 g/km.[2] For heavy-duty vehicles, Euro V from Directive 2005/55/EC (effective September 2008 for new engines, January 2009 for vehicles) reduced NOx to 2.0 g/kWh but kept PM at 0.02 g/kWh, emphasizing selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems for NOx control amid growing evidence of urban air quality issues from incomplete combustion particulates.[3] These changes aimed to address ultrafine particles but relied on the NEDC test cycle, which underestimated real-driving NOx emissions by factors of 4-7 for diesels, as later revealed by on-road testing.[9] Euro 6 standards, also under Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 as amended, mandated compliance for new light-duty types from September 2014 and all registrations by September 2015, slashing diesel NOx to 0.08 g/km, PM to 0.0045 g/km, and introducing a particle number (PN) limit of 6 × 10¹¹ particles/km to target nanoparticles evading mass-based PM filters.[2] Petrol direct-injection engines faced the same PN threshold, with CO steady at 0.5 g/km and HC+NOx at 0.17 g/km. For heavy-duty, Euro VI via Regulation (EC) No 595/2009 applied from December 2013 for new engines and September 2014 for vehicles, imposing NOx at 0.4 g/kWh, PM at 0.01 g/kWh, and PN limits, alongside in-service conformity requirements to verify durability.[3] Subsequent 2016-2017 amendments added Real Driving Emissions (RDE) testing using portable emissions measurement systems (PEMS) with conformity factors (initially 2.1 for NOx, tightened to 1.43 by 2021), addressing the gap between lab and road NOx outputs where Euro 5/6 diesels often emitted 5-10 times lab limits without advanced urea-SCR.[9]| Pollutant | Euro 4 Diesel (g/km) | Euro 5 Diesel (g/km) | Euro 6 Diesel (g/km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| NOx | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| PM | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.0045 |

| PN (particles/km) | - | - | 6 × 10¹¹ |

Introduction of Euro 7 and Future Iterations

The Euro 7 emission standards, formally established under Regulation (EU) 2024/1257 adopted by the European Parliament and Council on April 24, 2024, represent the most recent advancement in the European Union's framework for controlling pollutant emissions from road vehicles.[10] For the first time, the regulation unifies requirements for both light-duty vehicles (such as passenger cars and vans) and heavy-duty vehicles (including trucks and buses), extending beyond tailpipe emissions to include non-exhaust sources like brake and tire particles, as well as cold-start emissions and battery durability for electrified vehicles.[5] Implementation is phased: for light-duty categories (M1 and N1), new vehicle types must comply starting November 29, 2026, with all new registrations following by 2027; heavy-duty categories (M2, M3, N2, N3) face later deadlines, with new types required from 2027 and full applicability by 2028-2029.[11] These standards build on Euro 6 by imposing stricter limits—for instance, reducing nitrogen oxides (NOx) for light-duty diesels to 60 mg/km from 80 mg/km under certain conditions—while introducing real-world testing expansions and durability requirements up to 10 years or 124,000 miles for critical components.[2] The development of Euro 7 encountered significant delays and compromises amid industry opposition, particularly from the European Automobile Manufacturers' Association (ACEA), which argued that the original 2025 proposal would impose excessive costs—estimated at €5-15 billion annually—for marginal air quality gains, especially given the rising share of electric vehicles exempt from many tailpipe rules.[12] Initially proposed by the European Commission in November 2022 with a mid-2025 rollout for light-duty vehicles, the timeline was pushed back following trilogue negotiations, reflecting tensions between environmental advocates pushing for aggressive pollutant cuts (projecting up to 7,200 fewer premature deaths by 2050) and manufacturers citing technological and economic feasibility challenges.[13] The final regulation moderates some ambitions, such as relaxing particle number limits for gasoline direct injection engines and providing flexibility for small-volume producers, but retains innovative elements like mandatory on-board monitoring systems to ensure long-term compliance.[7] Looking to future iterations, no formal Euro 8 standards have been proposed as of 2025, with Euro 7 positioned as a transitional framework bridging current internal combustion engine regulations and the EU's broader decarbonization mandates.[3] Policymakers anticipate that subsequent pollutant controls will integrate with fleet-wide CO2 targets, which require zero grams per kilometer for new light-duty vehicles from 2035, effectively phasing out new fossil fuel sales and diminishing the relevance of tailpipe emission tiers.[14] Discussions in technical forums emphasize adapting standards for emerging technologies, such as hydrogen engines or advanced hybrids, but causal analyses suggest that air quality improvements will increasingly derive from vehicle electrification and turnover rather than iterative tightening of Euro-series limits, given non-exhaust emissions' growing dominance in urban pollution profiles.[15] Any post-Euro 7 revisions would likely prioritize enforcement of existing rules over new pollutant thresholds, pending evaluations of Euro 7's real-world efficacy through expanded remote sensing and durability data.Regulatory Framework

Legal Basis and Enforcement Mechanisms

The legal basis for European emission standards derives from EU legislation harmonizing type-approval requirements to ensure the free movement of vehicles while limiting pollutants, primarily under Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which empowers the adoption of measures for the internal market.[16] For light-duty vehicles, the foundational framework was established by Council Directive 70/220/EEC of 20 March 1970, which introduced initial exhaust emission limits and has been amended repeatedly to incorporate successive Euro standards up to Euro 4.[17] Subsequent regulations, such as Regulation (EC) No 715/2007, codified Euro 5 and Euro 6 limits for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, mandating compliance for new type-approvals from September 2009 and September 2014, respectively.[18] The Euro 7 standards, adopted on 24 April 2024 via Regulation (EU) 2024/1257, unify pollutant limits for both light- and heavy-duty vehicles, engines, and non-exhaust emissions (e.g., from brakes and tires), with applicability starting in 2027 for cars and vans and 2028 for trucks and buses. For heavy-duty vehicles, earlier standards relied on directives like 88/77/EEC (amended for Euro I to IV) and Regulation (EC) No 595/2009 for Euro VI, now consolidated under the Euro 7 framework.[19] Enforcement operates through a type-approval system governed by Regulation (EU) 2018/858, which designates national type-approval authorities in EU member states to certify compliance via accredited technical services conducting lab and real-driving emissions (RDE) tests.[20] Manufacturers must demonstrate conformity of production through statistical sampling and periodic audits, while in-service conformity checks—introduced for Euro 6 via on-road testing—require vehicles to meet limits over their useful life, with particle number and NOx thresholds enforced via portable emissions measurement systems (PEMS).[2] Non-compliance triggers remedial actions, including software updates or recalls, overseen by national market surveillance authorities empowered to seize vehicles, impose fines (up to €30,000 per non-compliant vehicle under some national implementations), and revoke approvals.[21] The European Commission enforces supranational oversight by monitoring member state implementation, initiating infringement proceedings under Article 258 TFEU for systemic failures, and coordinating EU-wide recalls, as seen in the Dieselgate scandal where fines exceeded €30 billion across manufacturers.[14] Recent enhancements under Euro 7 include extended durability requirements (up to 10 years or 124,000 km for light-duty) and mandatory reporting to bolster traceability and deterrence.Vehicle Categories and Applicability

European emission standards regulate exhaust emissions from new motor vehicles placed on the market in the European Union and European Economic Area member states, with applicability determined by vehicle categories defined under the EU type-approval framework in Regulation (EU) 2018/858, which incorporates UNECE classifications. These categories distinguish between passenger-carrying vehicles (M) and goods-carrying vehicles (N), with subcategories based on seating capacity, maximum mass, and intended use. Standards do not apply retroactively to existing vehicles but mandate compliance for type approvals and first registrations of new vehicles and engines.[2] The primary categories are outlined as follows:| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| M1 | Vehicles for carriage of passengers comprising no more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat and a maximum design mass not exceeding 3.5 tonnes.[22] |

| M2 | Vehicles for carriage of passengers with more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat and a maximum mass not exceeding 5 tonnes.[22] |

| M3 | Vehicles for carriage of passengers with more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat and a maximum mass exceeding 5 tonnes.[22] |

| N1 | Vehicles for carriage of goods with a maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tonnes.[22] |

| N2 | Vehicles for carriage of goods with a maximum mass exceeding 3.5 tonnes but not exceeding 12 tonnes.[22] |

| N3 | Vehicles for carriage of goods with a maximum mass exceeding 12 tonnes.[22] |

Compliance Testing and Certification Processes

The compliance testing and certification processes for European emission standards are governed by the EU type-approval framework, under which national type-approval authorities certify that vehicle types, engines, or systems meet specified pollutant limits before placement on the market. This involves submitting prototypes for testing to verify adherence to standards such as Euro 6 or Euro 7, with approvals valid EU-wide through Whole Vehicle Type Approval for complete vehicles. Manufacturers must demonstrate compliance via standardized laboratory and on-road tests, ensuring emission control systems function as designed, including durability requirements over the vehicle's useful life.[24][25] For light-duty vehicles, including passenger cars (category M1) and light commercial vehicles (N1, N2 up to 2,610 kg), certification requires chassis dynamometer testing under the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), which simulates driving cycles and measures emissions like CO, NOx, PM, and PN in g/km or #/km. Introduced via Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 and amended by (EU) 2018/1832, WLTP replaced the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) for new types from September 2017 and all registrations by September 2018. Complementing WLTP, Real Driving Emissions (RDE) testing uses Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) for on-road validation, covering urban, rural, and motorway segments over 90-120 minutes, with conformity factors (e.g., 1.43 for NOx under Euro 6d) allowing limited exceedance of lab limits to account for variability. In-service conformity (ISC) programs, including type-approval RDE and post-market surveillance via type 4 and 6 tests, ensure continued compliance after vehicles accumulate mileage.[2][26][27] Heavy-duty vehicles, such as trucks (N3) and buses (M3), undergo engine-focused certification under Euro VI, testing on engine dynamometers with the World Harmonised Transient Cycle (WHTC) for transient operation and World Harmonised Stationary Cycle (WHSC) for steady-state, yielding results in g/kWh. Regulation (EC) No 595/2009 establishes these rules, with implementing measures in (EU) No 582/2011 requiring on-board diagnostics, off-cycle emission checks, and PEMS-based on-road testing during type-approval. In-service conformity mandates PEMS field tests on vehicles after at least 25,000 km, where the 90th percentile of results must not exceed 1.5 times WHTC limits for gaseous pollutants under Euro VI-E, tightening to 1.0 under proposed Euro VII from 2027/2028. Conformity of production audits and durability demonstrations for pollution-control devices, such as selective catalytic reduction systems, are integral to maintaining certification.[3][25][28] These processes address historical gaps between laboratory and real-world emissions, as evidenced by scandals like Volkswagen's defeat devices, by incorporating RDE and ISC to enforce causal accountability for in-use performance, though conformity factors have been criticized for permitting some real-world exceedances.[29][27]Pollutant Emission Limits

Standards for Passenger Cars and Light-Duty Vehicles

European emission standards for passenger cars (category M1, vehicles with no more than eight seats and a maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tonnes) and light-duty vehicles (primarily category N1, goods vehicles with maximum mass ≤3.5 tonnes) regulate tailpipe emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM), and, from Euro 5 onward, particle number (PN). These limits, expressed in grams per kilometer (g/km), have tightened progressively across Euro stages, with separate thresholds for diesel (compression ignition) and petrol (positive ignition) engines to address differing combustion characteristics and pollutant profiles—diesel engines historically emitting higher NOx and PM, while petrol engines produce more CO and HC. Implementation dates refer to new type approvals, followed by all new vehicles 12-24 months later. Standards for N1 vehicles align closely with M1 but include reference mass-based classes (I, II, III), with Class I matching M1 limits and higher classes permitting elevated thresholds (e.g., up to 20% higher NOx for Class III under Euro 6).[2] For diesel passenger cars, Euro 1 (July 1992) set initial limits of 2.72 g/km CO, 0.97 g/km HC+NOx, and 0.14 g/km PM, evolving to Euro 6 (September 2014) with 0.5 g/km CO, 0.17 g/km HC+NOx, 0.08 g/km NOx, 0.005 g/km PM, and 6.0 × 10¹¹ particles/km (PN >23 nm). PM and PN apply to direct-injection engines, reflecting diesel's soot challenges. Euro 2 distinguished indirect (IDI) and direct injection (DI), with DI facing stricter PM (0.10 g/km vs. 0.08 g/km). Subsequent stages separated HC and NOx, reducing NOx by over 90% from Euro 1 levels through technologies like selective catalytic reduction.[2]| Stage | Date (TA) | CO (g/km) | HC+NOx (g/km) | NOx (g/km) | PM (g/km) | PN (/km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro 1 | 1992.07 | 2.72 | - | 0.97 | 0.14 | - |

| Euro 2 | 1996.01 | 1.0 | - | 0.7-0.9 | 0.08-0.10 | - |

| Euro 3 | 2000.01 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.050 | - |

| Euro 4 | 2005.01 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.025 | - |

| Euro 5 | 2009.09 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.005 | (5b: 6×10¹¹) |

| Euro 6 | 2014.09 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.005 | 6×10¹¹ |

| Stage | Date (TA) | CO (g/km) | HC (g/km) | NOx (g/km) | PM (g/km) | PN (/km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|