Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

European Civil Service

View on Wikipedia| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The European Civil Service is a generic term applied to all staff serving the institutions and agencies of the European Union (EU). Although recruitment is sometimes done jointly, each institution is responsible for its own internal structures and hierarchies.

Principles of public service

[edit]The rules, principles, standards and working conditions of the European civil service are set out in the Staff Regulations.[1]

In 2012, the European Ombudsman summarised the following five principles of public service which should apply to all staff of the EU institutions:[2]

- 1. Commitment to the European Union and its citizens

- 2. Integrity

- 3. Objectivity

- 4. Respect for others

- 5. Transparency

Staff

[edit]The European Commission's civil service is headed by a Secretary General, currently Ilze Juhansone holding the position.[3] According to figures published by the commission, 24,428 persons were employed by the commission as officials and temporary agents in their 2016 budget.[4] In addition to these, 9,066 additional staff were employed; these are largely people employed on time-limited contracts (called "contractual agents" in the jargon), staff seconded from national administrations (called "Detached National Experts"), or trainees (called "stagiaires"). The single largest DG is the Directorate-General for Translation, with 2261 staff.[5]

Popular terminology

[edit]European civil servants are sometimes referred to in the anglophone press as "Eurocrats" (a term coined by Richard Mayne, a journalist and personal assistant to the first Commission president, Walter Hallstein).[6] High-ranking officials are sometimes referred to as "European Mandarins".[7]

These terms are sometimes erroneously used by the anglophone press, usually as a derogatory slur, to describe Members of the European Parliament, or European Commissioners. MEPs are directly elected representatives, whilst the European Commissioners, despite often being confused as civil servants, are politicians holding public office and accountable to the European Parliament. Much like government ministers at the national level, they instruct the policy direction of the civil service.

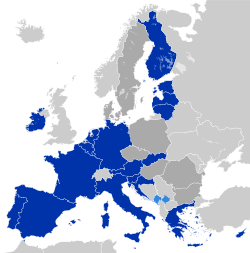

Nationality

[edit]As of 1 January 2018 there are staff from all member states, with the largest group being Belgian (15.7% – 5,060 out of 32,196). From the larger member states, 12.1% were Italian, 9.9% French, 7.5% Spanish, 6.7% German, 4.4% Polish and 2.8% British.[5]

Most administration is based in the Belgian capital,[5] Often, those states under-represented in the service tend to have more of their nationals in the higher ranks.[8]

Qualifications

[edit]The qualifications needed to enter the European civil service depend on whether the job is a specialist one and the grade.[9] One of the entry qualifications for the European civil service is that the candidate speak at least two of the official European languages, one of which must be English, French or German. Candidates whose mother tongue is English, French or German must pass the competition for entry in one of the other two official languages.

Prior to their first promotion, officials must demonstrate competence in a third EU official language.

A candidate also needs to have a first degree in any discipline with a diploma issued by a University from any member state of the EU, or, if issued by a University from a non-EU member state it must be homologated by at least one of them in order to be eligible. The services have traditionally hired candidates with degrees in law, Economics, or Audit; competition is tougher for graduates of all other disciplines, although the procedure for the open competitions, known as "Concours", is now under review.

Grades

[edit]Staff are divided into a set of grades: from AD 5, the most junior administrator grade, to AD 16, which is a director-general (AD = administrator). Alongside the AD category is AST (assistant). It is now possible for civil servants to be promoted from AST to AD grade, not previously possible (see below); however in practice the grades remain entrenched.[10] While promotion is in theory according to merit, many management posts are now taken by officials 'parachuted in' from member states. Moreover, staff reforms introduced in 2004 have severely reduced the possibilities for career progression and have created divisions within the service, with pre-2004 entrants enjoying greater pay and privileges. According to the commission's own internal statistics, even though new officials possess an average of eight years work experience, it would take an average of over 40 years to climb from AD 5 to AD 16.

Prior to this new system, introduced in the 2000s (decade), civil servants were traditionally divided into four categories. "A" was policy making (what is now AD), "B' was implementing, "C" was secretarial and "D" was drivers and messengers (B, C and D are now all part of the AST category). There were various grades in each category. The major ranks used to be in the form of A8 (new appointment without prior work experience) to A1 (director-general).[10]

Salary and allowances

[edit]EU civil and other servants work 40 hours a week, though they are theoretically available 24/7.[citation needed] They receive a minimum of 24 days of leave a year (maximum of 30), with additional leave entitlements on grounds of age, grade but no longer distance from home country (this is now a flat-rate 2.5 days for all)[citation needed].

The lowest grades receive between €1,618.83 gross (FG 1 step 1)[11] each month, while the highest grades (AD 15–16 – i.e. Directors General at the end of their career) receives between €14,822.86 and €16,094.79 a month. This salary is taxed by the EU, rather than at the national level. Taxation varies between 8% and 45% depending on individual circumstances. This is paid into the Community budget.[12]

Earnings are augmented by allowances, such as allowances for those living outside their own country, those who are the principal earner in their household, those with children in full-time education, and those who are moving home in order to take up a position or leaving the service. Earnings are also lowered by various additional taxes (i.e. "Special Levy" alias 'crisis levy' introduced in 1973 and increasing regularly every year)[13] and indexes (for EU staff working out-side Brussels).

For a contribution of 2% basic salary, employees are provided with health insurance which covers a maximum of 85% of expenses (100% for serious injury).[12] Employees have the right to a parental leave of six months per person and child during which they obtain an allowance and have (as of January 2014) the possibility of an extension by further 6 months with a smaller allowance.[14]

Salaries were considerably reduced for new entrants from 1 May 2004 onwards as a result of a significant number of reforms effected by Commissioner Neil Kinnock. Staff undertaking the same work may receive very different salaries, depending on their date of recruitment. Careers are also sharply affected, with new staff tending to constitute a 'second division' of workers with limited managerial prospects. As a consequence of these changes, the institutions recruit with difficulty staff from certain countries like UK, Luxembourg, Denmark as wages are the same or lower than in the home country. For example, a Director General's salary is below what a senior executive with similar responsibilities could expect to be earning at the end of their career in the UK and in some countries (like Luxembourg) the lowest wages (FG I – FG II) are even under the legal minimum salary in the respective country, which raise the question about legality of such terms of employment.[citation needed]

In January 2010, The European Commission took the EU member states to court over the Member States' refusal to honour a long-standing formula under which wages for the staff of the European institutions are indexed to the salaries of national civil servants.[15] The formula led to a salary adjustment of 3.7% but the council, representing the member states, was only willing to grant a pay rise of 1.85%.[16] In November 2010, the European Court of Justice ruled that there was no legal basis for the council to set the pay rise to 1.85%.[17] It has been noted that the ECJ judges who would decide in this case would be themselves to benefit from any salary increase agreed.[18] To be noted that the index is published and applied one year and half later, and this delay cause the quarrels like in the 2010 (full crisis) where should be applied the adaptation related to the increases of wages of the national civil servants from 2007 to 2008; while in 2011 the index was already negative (as the national wages has been lowered).

Pensions

[edit]Employees contribute about 11.3% of their basic salary to a pension scheme.[19] This scheme does not constitute a separate, ring-fenced pension fund; rather, pension payments are made from the general administrative budget of the commission.

Pensions are paid as a percentage of the final basic salary, with the percentage increasing by an annual accrual rate (a fixed percentage per year of service) up to a ceiling of 70%. Early retirement is possible as of 58 years, albeit with the pension being reduced by a fixed pension reduction coefficient per year before the pensionable age. For staff who entered service 2014 or later, the annual accrual rate is 1.8%, the pensionable age is 66 years, early retirement is possible as of 58 years with a pension reduction coefficient of 3.5%.[14][20]

Different conditions apply to those hired before 2014: Those who entered service between 1 May 2004 and 31 December 2013 have an annual accrual rate of 1.9%, a pensionable age between 63 and 65 years, the same early retirement age limit of 58 years and a lower pension reduction coefficient of 1.75% for years above the age of 60. Those in place before 1 May 2004 have an annual accrual rate of 2.0%, a pensionable age between 60 and 65 years, the same early retirement age limit of 58 years and a lower pension reduction coefficient of 1.75% for years above the age of 60.[14]

Before 1 January 2014, other conditions had applied: For those who entered service on 1 May 2004 or later, the pensionable age had been 63 years, and for those who entered service before 1 May 2004 it had been between 60 and 63 years. Early retirement had been possible as of 55 years for all staff, with a pension reduction coefficient of 3.5% per year before the pensionable age, except that a small percentage of officials could retire early without that pension reduction if it was in the interest of the service.[21] To mitigate the changes implemented as of 2014, transitional pension rules were put in place for staff in place on 1 January 2014, which included setting the pensionable age for staff between 55 and 60 years of age on 1 January 2014 to lie between 60 and 61 years. Transition measures applied also to early retirement: Staff already aged 54 years or older on 1 January 2014 could still retire, albeit with application of the pension reduction coefficient, in 2014 or 2015 at the age of 56 years or in 2016 at the age of 57 years.[14][22]

Before 1 May 2004, the pensionable age had been 60 years. When this age was raised in 2004, this was accompanied by transition measures so that it remained unchangedly at 60 for officials aged 50 or more as well as for officials who had already completed 20 years of service or more on 1 May 2004, and it varied from 60 years and 2 months to 62 years and 8 months for officials who were aged 30 to 49 on 1 May 2004.[21]

Recruitment

[edit]Recruitment is on the basis of competitions organised centrally by EPSO (European Personnel Selection Office) on the basis of qualifications and of the need for staff.

Organisational culture

[edit]During the 1980s, the commission was primarily dominated by French, German and Italian cultural influences, including a strictly hierarchical organisation. Commissioners and Directors-General were referred to by their title (in French) with greater prestige for those of higher ranks. As one former servant, Derk Jan Eppink has put it, even after new staff had passed the tough entrance exams: "Those at the top counted for everything. Those at the bottom counted for nothing."[23] One example of this was the chef de cabinet of President Jacques Delors, Pascal Lamy, who was particularly notable for his immense influence over other civil servants. He became known as the Beast of the Berlaymont, the Gendarme and the Exocet due to his habit of ordering civil servants, even Directors-General (head of departments) "precisely what to do – or else." He was seen as ruling Delors's office with a "rod of iron", with no-one able to bypass or manipulate him and those who tried being "banished to one of the less pleasant European postings".[24]

However, since the enlargement of the EU, and therefore the arrival of staff from the many newer Member States, there has been a change in the culture of the civil service. New civil servants from northern and eastern states brought in new influences while the commission's focus has shifted more to "participation" and "consultation". A more egalitarian culture took over, with Commissioners no longer having a "status equivalent to a sun God" and, with this new populism, the first women were appointed to the Commission in the 1990s and the service gained its first female secretary general in 2006 (Catherine Day). In stark contrast to the 1980s, it is not uncommon to see men without ties and children playing football in the corridors.[25]

Criticisms

[edit]It has been alleged that, for want of a common administrative culture, European Civil Servants are held together by a "common mission" which gives DGs a particularly enthusiastic attitude to the production of draft legislation regardless of the intentions of the Commissioner.[26] They are also notably bound by their common procedures, in the absence of a common administrative culture, which are best known by the Secretariat-General, thus considered a prestigious office, just below the President's cabinet.[27]

There has been some criticism that the highly fragmented DG structure wastes a considerable amount of time in turf wars as the different departments and Commissioners compete with each other, as is the case in national administrations. Furthermore, the DGs can exercise considerable control over a Commissioner unless the Commissioner learns to assert control over his/her staff.[28][29] The DGs work closely with the Commissioner's cabinet. While the DG has responsibility for preparation of work and documents, the cabinet has responsibility for giving the Commissioner political guidance. However, in practice both seek a share of each other's work.[30] It has been alleged that some DGs try to influence decision making by providing Commissioners with briefing documents as late and large as possible, ensuring that the Commissioner has no time to do anything but accept the version of facts presented by the DG. In doing this the DG is competing with the cabinet, which acts as a "bodyguard" for the Commissioner.[31]

Organisational structure

[edit]The commission is divided into departments known as Directorates-General (DGs or the services), each headed by a director-general, and various other services. Each covers a specific policy area or service such as External Relations or Translation and is under the responsibility of a European Commissioner. DGs prepare proposals for their Commissioners which can then be put forward for voting in the college of Commissioners.[32]

Whilst the commission's DGs cover similar policy areas to the ministries in national governments, European Civil Servants have not necessarily been trained, or worked, in a national civil service before employment in the EU. On entry, they do not therefore share a common administrative culture.

List of Directorates-General

[edit]The Directorates-General are divided into four groups: Policy DGs, External relations DGs, General Service DGs and Internal Service DGs. Internally, the DGs are referred to by their abbreviations; provided below.

List of Services

[edit]| Services | |

|---|---|

| Service | Abbreviation |

| European Commission Library | EC Library |

| Inspire, Debate, Engage and Accelerate Action | IDEA |

| European Anti-Fraud Office | OLAF |

| European Commission Data Protection Officer | DPO |

| Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority | HERA |

| Historical Archives of the European Union | HAEU |

| Infrastructures and Logistics – Brussels | OIB |

| Infrastructures and Logistics – Luxembourg | OIL |

| Internal Audit Service | IAS |

| Legal Service | SJ |

| Office for Administration and Payment of Individual Entitlements | PMO |

| Publications Office | OP |

| Recovery and Resilience Task Force | RECOVER |

| European Personnel Selection Office | EPSO |

| European School of Administration | EUSA |

| Service for Foreign Policy Instruments | FPI |

List of Executive Agencies

[edit]| Executive Agencies | |

|---|---|

| Executive Agency | Abbreviation |

| European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency | CINEA |

| European Education and Culture Executive Agency | EACEA |

| European Health and Digital Executive Agency | HADEA |

| European Innovation Council and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Executive Agency | EISMEA |

| European Research Council Executive Agency | ERCEA |

| European Research Executive Agency | REA |

Staff trade unions

[edit]The European Civil servants working for the European Civil Service can vote for representatives amongst several trade unions which then sit in representatives instances of the institution, for example:

- Union Syndicale

- European Civil Service Federation (FFPE)

- Union 4 Unity

- Renouveau et Démocratie

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Eppink, Derk-Jan (2007). Life of a European Mandarin: Inside the Commission. Translated by Ian Connerty (1st ed.). Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo. ISBN 978-90-209-7022-7.

- ^ Consolidated text (1 January 2023): Regulation No 31 (EEC), 11 (EAEC), laying down the Staff Regulations of Officials and the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community

- ^ Ombudsman, European (19 June 2012). "Public service principles for the EU civil service". www.ombudsman.europa.eu.

- ^ "Secretary-General Ize Juhansone". European Commission. European Commission. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Huggins, Christopher (3 June 2016). "How many people work for the EU?". News and Events. Keele University. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "Civil Service: Staff figures". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Tindall, Gillian (22 December 2009). "Richard Mayne obituary". The Guardian. London. p. 30. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Eppink, Derk-Jan (2007). Life of a European Mandarin: Inside the Commission. Lannoo. ISBN 978-9020970227.

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.35

- ^ "Entry requirements". Job profiles European Union official. UK Government Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ a b Eppink, 2007, p.37

- ^ Chapter 7, page II-30, Staff Regulation,

- ^ a b COUNCIL REGULATION (EC, EURATOM) No 723/2004, Annex I, Amendment 60

- ^ "Special Levy". Think Tank [decommissioned 12 October 2020]. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Summary document on changes relating to Staff Regulations review. Measures included in the compromise text agreed by COREPER on 28 June 2013 and voted in plenary session of the European Parliament on 2 July 2013. Ref. Ares(2013)2583641 – 05/07/2013" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Glossary of terms – ANZ". www.anz.com.

- ^ "EU civil servant pay row goes to court". euractiv.com. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "EU officials win pay rise battle with member states". EuroActiv. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (6 January 2010). "EU mounts challenge to MEP pay rise cuts". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "COUNCIL REGULATION (EU, EURATOM) No 1295/2009 of 22 December 2009 adjusting with effect from 1 July 2009 the rate of contribution to the pension scheme of officials and other servants of the European Union".

- ^ "Permanent officials". European Commission. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Retirement pension and early retirement: Frequently asked questions". European Commission. 6 January 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012.

- ^ Irene Souka (July 2013). "Review of the Staff Regulations" (PDF). p. 12.

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.32

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.22–3

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.34–5

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.111

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.218

- ^ Amies, Nick (21 September 2007). "Former EU Mandarin Spills the Beans on Commission Intrigue". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ Mahony, Honor (17 October 2007). "EU carefully manages PR through 1000s of press releases". EU Observer. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.109

- ^ Eppink, 2007, p.107-8

- ^ "Institutions of the EU: The European Commission". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- ^ "European Commission: Departments (Directorates-General) and services". Retrieved 29 December 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Eppink, Derk-Jan (2007). Life of a European Mandarin: Inside the Commission. Translated by Ian Connerty (1st ed.). Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo. ISBN 978-90-209-7022-7.

External links

[edit]- European Commission Civil Service, Europa (web portal)

- Opportunities in Europe UK Cabinet Office: Careers

- "Regulation No 31 (EEC), 11 (EAEC), laying down the Staff Regulations of Officials and the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community". Retrieved 19 November 2023., Consolidated text d.d. 2023-01-01

European Civil Service

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in Post-War Integration

The European civil service traces its origins to the establishment of the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), formed as the first supranational administrative apparatus in post-World War II Europe. The ECSC Treaty, signed on 18 April 1951 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany, entered into force on 23 July 1952, with the High Authority commencing operations on 10 August 1952 in Luxembourg.[6] This body was tasked with regulating coal and steel production—industries central to rearmament and prior conflicts—to foster economic interdependence and render war between France and Germany "materially impossible," as articulated in the preceding Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950.[7][8] The High Authority's bureaucracy began on a modest scale, comprising a limited number of technical specialists focused on oversight functions such as production quotas, price stabilization, and cartel enforcement, rather than broad governance.[9] This lean structure reflected the ECSC's experimental nature as a targeted supranational experiment amid national reconstructions, prioritizing expertise in heavy industry over expansive administrative layers.[10] Drawing from the French tradition of centralized, meritocratic administration—epitomized by Jean Monnet's role as the High Authority's first president—the service instituted early principles of independence from national governments. Members of the High Authority were appointed as independent figures, not national delegates, to prioritize Community interests, a model extended to supporting staff through oaths of loyalty to the supranational mandate.[7][6] This design aimed to insulate decision-making from interstate rivalries, enabling direct enforcement powers like fines on non-compliant firms, though initial operations revealed tensions between supranational ambitions and member-state sovereignty.[11]Evolution Through EU Treaties

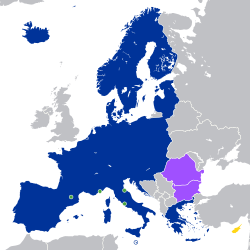

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), signed on 25 March 1957 and entering into force on 1 January 1958, established the Commission as the EEC's independent executive institution, responsible for initiating policy, enforcing treaty obligations, and managing supranational functions such as the creation of a customs union and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This foundational treaty provided the legal basis for the European civil service, initially comprising a modest administrative apparatus in Brussels to operationalize economic integration among the six founding members (Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands). The Commission's staff focused on technical implementation of treaty goals, including tariff reductions and competition policy, marking the shift from intergovernmental cooperation to a permanent bureaucratic structure insulated from direct national control.[12][13] The Merger Treaty, signed on 8 April 1965 and effective from 1 July 1967, unified the separate executive bodies of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC High Authority), EEC Commission, and European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom Commission) into a single European Commission, alongside a single Council. This consolidation streamlined the civil service by merging parallel administrative hierarchies, reducing redundancies, and enabling coordinated staffing across disparate policy areas like industrial policy, nuclear research, and economic regulation. The reform facilitated a more integrated bureaucracy capable of supporting multifaceted Community objectives, with staff reallocations emphasizing expertise in cross-sectoral implementation rather than siloed operations.[14] The Treaty on European Union, signed on 7 February 1992 and entering into force on 1 November 1993 (commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty), elevated the EEC to the European Community within a three-pillar EU structure, expanding the Commission's mandate to include coordination of economic and monetary union (EMU), trans-European networks, and limited roles in the second (Common Foreign and Security Policy) and third (Justice and Home Affairs) pillars. These enhancements required civil service adaptations for broader competencies, such as monetary policy oversight leading to the European Central Bank and cohesion fund management, which drove administrative growth to handle intensified regulatory and inter-pillar coordination demands. Commission staff numbers expanded from several thousand in the 1970s—reflecting early policy builds like CAP expansion—to over 30,000 by the early 2000s, correlating with treaty-driven policy proliferation including the single market's completion.[15][16]Key Reforms and Enlargements

The enlargements of 2004, which added ten Central and Eastern European countries along with Cyprus and Malta, and 2007, incorporating Bulgaria and Romania, necessitated substantial adaptations in the EU civil service to incorporate nationals from the new member states and maintain geographical balance. These changes triggered policies promoting representative bureaucracy, with deliberate recruitment drives to ensure passive representation from accession countries, reflecting the EU's expanded demographic composition.[17][18] Staff numbers in the European Commission and other institutions grew rapidly to handle increased administrative demands, alongside the introduction of diversity measures such as quotas for hiring from underrepresented nationalities to align the workforce with the EU's broader membership.[19] In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the EU institutions pursued efficiency-driven reforms, including a proposed 5% reduction in civil service staff across all bodies from 2013 to 2017, achieved primarily through natural attrition without forced redundancies.[20] These measures also involved extending the standard working week from 37.5 to 40 hours and enhancing productivity protocols, amid broader austerity efforts to curb administrative costs. Outsourcing of non-core functions, such as IT services and certain support roles, was expanded to complement internal staff reductions and optimize resource allocation.[20] Brexit prompted further structural adjustments, particularly the repatriation of UK nationals from the EU civil service, with contracts for temporary, contract, and parliamentary staff from the UK terminated as of January 1, 2021, affecting hundreds of positions.[21] Permanent officials of British nationality faced restrictions on continued service unless they acquired citizenship of an EU-27 member state, leading to a reconfiguration of staff demographics and intensified recruitment from remaining member states to fill expertise gaps in areas like trade and regulatory policy.[22] These shifts underscored the civil service's vulnerability to member state withdrawals, prompting reviews of nationality rules under Article 336 TFEU.[22]Legal Framework and Principles

Fundamental Principles of Service

The fundamental principles of the European civil service, primarily governing officials in the European Commission, mandate independence, impartiality, objectivity, and loyalty exclusively to the European Union. These obligations require civil servants to execute duties solely with the Union's interests in mind, prohibiting them from seeking or accepting instructions from member state governments, other institutions, or external entities.[23][4] This supranational framework, codified in Article 11 of the Staff Regulations of Officials of the European Union, ensures decisions prioritize collective European objectives over national preferences, fostering a professional ethos detached from member state influences.[24] Complementing these duties, Article 17(1) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) establishes the Commission's collegial independence, with members selected for their unquestionable independence and commitment to European integration; this principle cascades to civil servants through institutional hierarchy, holding them accountable to the Commission President as the executive head.[25] Officials must abstain from any conduct incompatible with their roles, including conflicts of interest or external pressures that could compromise impartiality, as reinforced in Article 12 of the Staff Regulations.[23] Such provisions underscore a causal commitment to unbiased policy implementation, where loyalty binds servants to Union treaties and objectives rather than bilateral or domestic agendas. To safeguard these principles, mechanisms include whistleblower protections enabling officials to report suspected irregularities or breaches of EU law without fear of reprisal, supported by internal procedures and the broader EU Directive on whistleblower safeguards against retaliation such as demotion or dismissal.[26] This framework, operational since the 1962 Staff Regulations and updated through reforms, promotes transparency while maintaining hierarchical oversight to prevent abuse.[23]Staff Regulations and Legal Basis

The Staff Regulations of Officials of the European Union (Regulation No 31 (EEC), 11 (EAEC)), adopted on 30 June 1962 and applicable from 5 March 1968, together with the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants (CEOS), constitute the core codified framework regulating the rights, obligations, and employment conditions of EU institutions' personnel.[27] These instruments establish uniform rules across EU bodies, including recruitment confirmation, remuneration, pensions, and termination procedures, with consolidated versions updated annually to reflect amendments./2024-01-01/eng) The regulations primarily apply to permanent officials (Category I to IV staff appointed after open competition), who enjoy tenure subject to satisfactory performance during a mandatory nine-month probationary period, after which they are confirmed in service unless disciplinary grounds intervene.[27] Temporaries, including temporary agents under Article 2(a), (b), and (d) of the CEOS for roles requiring specialist expertise or short-term needs, face contracts limited to up to four years with possible renewal, alongside probation of six to nine months depending on duration.[28] Contract staff (Article 3a CEOS) and other non-permanent categories, such as seconded national experts or agency workers, receive analogous protections scaled to their engagement type, excluding full tenure rights.[27] Disciplinary measures, outlined in Articles 59-66 for officials and paralleled in CEOS, range from warnings and reprimands to suspension without pay, demotion, or compulsory retirement, triggered by faults like negligence or misconduct, with appeals possible.[27] Major revisions in 2014, via Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1023/2013 effective 1 January 2014, aimed to enhance administrative flexibility by reforming career streams, increasing mobility requirements, and adjusting pension accruals to curb costs amid fiscal pressures post-2008 crisis.[29] Salary adjustments in 2023 incorporated annual updates under the 2014-2023 method, applying a 4.4% increase tied to EU economic indicators and productivity gains, extending prior freezes and solidarity levies.[27] These changes apply until at least 31 December 2023, with post-2023 mechanisms pending interinstitutional agreement.[30] Judicial oversight of disputes arising under the regulations shifted in 2016 when the EU Civil Service Tribunal, established in 2004 for staff litigation, was dissolved on 1 September 2016, with its jurisdiction merging into the General Court of the EU to streamline proceedings and expand judicial capacity to 54 judges.[31] The General Court now handles direct actions by officials and servants, ensuring enforcement of regulations through preliminary rulings and annulments, subject to appeal to the Court of Justice.[32] This reform addressed backlog concerns while preserving specialized review of employment claims.[33]Independence and Loyalty Obligations

EU officials are required to uphold strict independence in performing their duties, as mandated by Article 17 of the Staff Regulations, which states that they "shall be independent" and must not seek or accept instructions from national governments or external entities. This principle ensures that civil servants prioritize the general interest of the Union over any national or personal affiliations. Complementing this, Article 11 imposes a duty of loyalty, requiring officials to "carry out their duties and conduct themselves solely with the interests of the Union in mind" and to abstain from any incompatible actions or behavior.[34] Upon appointment, officials affirm this commitment through a solemn declaration to execute their roles in accordance with the EU Treaties and institutional rules, reinforcing allegiance to supranational objectives.[24] These obligations can generate conflicts with national citizenship duties, as EU staff must disregard instructions from their home governments, even in policy areas like foreign affairs or economic coordination where national priorities clash with Union goals. For instance, the prohibition on external influences aims to prevent national lobbying, but it places officials in a position where loyalty to EU integration—embodied in treaty principles such as sincere cooperation under Article 4(3) TEU—may override domestic allegiances or public service norms in member states. In practice, such tensions have surfaced in disputes over EU competence, where civil servants' impartiality toward Union law supersedes national directives, though documented cases of direct clashes remain limited due to the supranational selection process that detaches staff from national hierarchies.[4] Allegations of politicization challenge the neutrality of senior roles, particularly Directors-General, whose appointments are proposed by the Commission President and approved by the College, often reflecting alignment with the executive's political guidelines despite statutory independence. Empirical analysis of bureaucratic profiles reveals growing politicization in the Commission's upper echelons since the 1990s, with an increase in officials possessing prior political experience—such as national ministry roles or advisory positions—correlating with institutional reforms like the 2000 White Paper on Reform, which emphasized managerial accountability to political leadership. This trend, while not extending deeply into mid-level ranks, suggests that loyalty obligations may bend toward Commission priorities in strategic policymaking, potentially undermining pure bureaucratic impartiality.[35][36] The framework's emphasis on tenure stability bolsters independence by limiting dismissals to severe misconduct under Articles 59–62 of the Staff Regulations, which require due process and appeal to the General Court, resulting in rare terminations that preserve job security against political pressures. This high protection level—evident in the predominance of permanent contracts and low turnover in core functions—facilitates long-term expertise but can entrench resistance to shifts in EU priorities, as accountability relies more on internal discipline than frequent renewal.[24]Recruitment and Qualifications

Selection Processes and Competitions

The European Personnel Selection Office (EPSO) organizes competitive examinations, known as concours, to select candidates for permanent positions in the administrator (AD) and assistant (AST) function groups of the EU civil service.[37] These merit-based processes emphasize general and specific competencies through multi-stage assessments, including eligibility screening, computer-based tests on verbal, numerical, and abstract reasoning, as well as evaluation of EU knowledge and professional skills.[38] Successful candidates are placed on reserve lists from which EU institutions recruit, typically starting at AD5 or AST3 grades.[39] Competitions are launched in annual or targeted cycles, often attracting tens of thousands of applications per year for a limited number of vacancies.[40] The selection involves rigorous phases such as written tests, group exercises, oral presentations, and structured interviews at an assessment center, designed to identify high-performing individuals capable of serving the EU's multilingual and multicultural environment.[38] Overall processing times from application to reserve list publication average 6 to 12 months, reflecting the volume of candidates and complexity of evaluations.[41] Success rates remain low, typically under 5%, with only a fraction of applicants advancing to final recruitment by institutions.[40] In response to critiques of rigidity and delays in traditional concours, the EU has diversified entry mechanisms following the European Court of Auditors' Special Report 24/2024, which examined civil service workforce management.[42] Institutions now incorporate lateral entry channels for specialized experts, such as temporary agents or seconded professionals, to reallocate talent swiftly to priority areas like digitalization and emerging policy needs, bypassing full concours for targeted roles while maintaining merit principles.[42] This shift aims to enhance agility without compromising the core competitive framework, though it has raised questions about consistency in standards across entry paths.[43]Nationality Requirements and Quotas

The nationality requirements for the European Civil Service stipulate that candidates must hold the nationality of a member state of the European Union, as outlined in Article 12(2) of the EU Staff Regulations, ensuring that recruitment draws exclusively from EU citizens to maintain institutional loyalty and alignment with Union objectives. This provision, combined with Article 27 of the same regulations, mandates recruitment on the broadest possible geographical basis to achieve an equitable distribution reflective of member states' diversity, without formal quotas but with guiding rates calibrated to each state's population share in the EU (approximately proportional to demographic weight). A significant under-representation is defined when a member state's staff proportion dips below 80% of its guiding rate, prompting targeted recruitment measures such as action plans coordinated with under-represented governments to prioritize nationals in competitions and internal promotions. Historically, this framework has resulted in persistent imbalances favoring certain member states, with Belgian nationals consistently over-represented—comprising around 12-15% of Commission staff despite Belgium's 2.1% share of EU population as of 2023—due to the institutions' Brussels headquarters facilitating local recruitment and familiarity advantages.[44] [45] French nationals, leveraging linguistic and cultural ties from the Union's foundational era, also maintained disproportionate influence in senior roles until the 1990s, though their share has moderated to near population parity (about 17% staff vs. 16.7% population).[46] Benelux countries as a group exhibited over-representation in the pre-2004 era, when the six founding members dominated staffing, reflecting causal factors like early integration proximity rather than merit-based selection alone. Following the 2004 and 2007 enlargements incorporating ten Central and Eastern European states, the Commission implemented compensatory mechanisms, including reserved trainee positions and outreach campaigns, to elevate representation from these newcomers, whose combined population share exceeds 20% yet staff levels hovered at 10-12% by 2023.[47] [48] Despite these efforts, under-representation endures—e.g., Poland at roughly 4% staff versus 7.8% population—attributed to lower application rates from language barriers and perceived cultural mismatches, fueling critiques that geographical imperatives undermine pure meritocracy while failing to fully rectify disparities.[49] The European Court of Auditors noted in 2024 that while institutions monitor these metrics annually, enforcement lacks binding penalties, relying instead on voluntary national action plans, which have yielded incremental gains but persistent East-West divides.[42]Educational and Professional Criteria

Candidates for administrator (AD) positions in the European Civil Service must possess a university degree attesting to the successful completion of studies lasting at least three years, enabling recruitment at entry-level grade AD5 for generalist roles.[50][39] Specialist competitions, such as those for economists, lawyers, or IT experts, typically require this educational baseline plus several years of relevant professional experience to demonstrate sector-specific expertise; in select cases, equivalencies allow professional training of post-secondary level supplemented by at least three years of pertinent experience to substitute for higher academic qualifications.[37][51] Newly recruited officials undergo mandatory induction training organized by the European School of Administration (EuSA), an EU entity dedicated to delivering specialized learning programs that cover institutional procedures, policy frameworks, and essential operational skills for staff across EU institutions and agencies.[52][53] This initial phase ensures rapid integration and alignment with service obligations. The EU Staff Regulations mandate ongoing training to foster lifelong learning, compelling institutions to provide opportunities for skill enhancement amid evolving demands; recent priorities, aligned with the 2025 Council Recommendation on digital skills and the Digital Decade initiative, emphasize proficiency in digital competencies, including data analysis and cybersecurity, integrated into EPSO assessments and EuSA curricula to equip civil servants for technological advancements in public administration.)[54][38]Organizational Structure

Directorates-General and Policy Areas

The European Commission's Directorates-General (DGs) serve as the core administrative divisions, each tasked with formulating, executing, and overseeing EU policies within designated sectors. Headed by a Director-General, these units operate under the strategic direction of a Commissioner from the College of Commissioners, ensuring alignment with the Commission's political priorities. DGs employ specialized expertise to draft legislation, manage budgets, conduct analyses, and coordinate with member states, with their work grounded in the Commission's right of initiative under the Treaty on European Union.[55] As of 2024, the Commission maintains 33 DGs, spanning diverse policy fields from economic governance to external relations. Prominent examples include DG AGRI, which administers the Common Agricultural Policy and rural development programs affecting over 40% of the EU budget; DG TRADE, responsible for negotiating trade agreements covering 70% of EU external trade; DG ENV, focused on environmental standards and nature restoration initiatives; and DG COMP, enforcing antitrust rules with fines exceeding €10 billion in recent years. Other key DGs encompass DG CLIMA for greenhouse gas reduction targets, DG ENER for energy security and diversification, and DG GROW for single market integration and industrial competitiveness.[56][57] This structure, while enabling specialized focus, has drawn criticism for fostering fragmentation and operational overlaps, particularly in transversal domains. For instance, climate-related responsibilities are distributed across DG CLIMA, DG ENV, DG ENER, and elements of DG MOVE, complicating unified action and resource allocation amid EU targets like net-zero emissions by 2050. In competition policy, DG COMP's remit intersects with DG TRADE's subsidies scrutiny and DG GROW's state aid assessments, leading to reported inefficiencies in case handling and inter-DG coordination. Such duplication, attributed to incremental expansions rather than holistic redesign, has been highlighted in audits noting redundant efforts in areas like sustainability transitions.[5][58] Staffing across DGs totals around 32,000 permanent and contract agents, with policy-oriented units absorbing the bulk—estimated at over two-thirds—aligned to shifting priorities such as green and digital transitions, while administrative services like DG HR and DG BUDG handle support functions. Between 2013 and 2023, policy DG headcounts fluctuated in response to mandates, with growth in areas like DG CLIMA (up 20% post-Paris Agreement) and stability in others amid overall fiscal constraints. This allocation prioritizes expertise in policy implementation over pure bureaucracy, though critiques persist on siloed expertise hindering cross-policy coherence.[59][5]Specialized Services and Agencies

The European Commission's specialized services encompass support entities distinct from its core policy-oriented Directorates-General, focusing on technical, statistical, and investigative functions essential to EU operations. Eurostat, the Commission's statistical office established in 1958 and headquartered in Luxembourg, compiles harmonized data on economic, social, and environmental indicators across member states, enabling evidence-based policymaking with a staff of approximately 1,000 as of 2023. Similarly, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), operational since 1999 and based in Brussels, conducts administrative investigations into fraud, corruption, and irregularities affecting the EU budget, recommending recoveries totaling over €10.2 billion from 2010 to 2024 while coordinating anti-fraud policies.[60] These services operate under direct Commission oversight, integrating specialized expertise into broader administrative frameworks without independent executive mandates.[61] Complementing these are the EU's decentralized agencies, numbering over 40 as of 2023, which execute delegated tasks in areas such as regulation, research, and operational support, often with semi-autonomous structures governed by secondary EU legislation.[1] Unlike core Commission bodies, these agencies are sited across member states to promote geographic balance and job distribution, a policy formalized in decisions like the 2016 relocation of agencies post-Brexit. For instance, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Amsterdam assesses and authorizes medicinal products for the EU market, wielding binding regulatory powers delegated by the Commission since its 1995 founding, with a 2023 budget of €457 million and staff exceeding 900.700320_EN.pdf) The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), relocated to Warsaw in 2004 and expanded via 2019 regulations, deploys personnel for border management and returns operations, exercising executive competencies under Commission guidelines with a 2023 staffing level of over 2,000 temporary agents.[1] Accountability for these agencies flows primarily to the Commission through multi-stakeholder management boards comprising member state representatives, Commission officials, and sometimes Parliament or stakeholder input, ensuring alignment with EU priorities while allowing task-specific autonomy. Founding regulations delineate varying independence levels; regulatory agencies like the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in Helsinki issue enforceable decisions on substance approvals, subject to Commission veto in limited cases, whereas operational entities like Frontex report directly on missions but face budgetary scrutiny from the Commission.[62] This structure balances delegation—evident in agencies handling 20-30% of certain Commission workloads—with hierarchical controls, including annual reporting and performance audits, to mitigate risks of mission creep observed in pre-2010 expansions.[63] Staff in these bodies, numbering tens of thousands collectively, are recruited under the EU Staff Regulations, mirroring Commission civil service standards but adapted to agency-specific needs.[1]Internal Hierarchy and Decision-Making

The European Commission's civil service operates within a hierarchical structure defined by function groups and grades, with administrators (AD) forming the core for policy and management roles. These span from grade AD5, the standard entry level for university graduates without substantial experience, to AD16, the pinnacle occupied by senior executives such as Directors-General.[64] Within Directorates-General, authority flows upward through reporting lines: policy officers and assistants at lower grades report to Heads of Unit (typically AD10–AD12), who in turn report to Directors (AD14–AD15), Deputy Directors-General, and the Director-General, ensuring specialized expertise aligns with broader institutional objectives.[65] Decision-making processes emphasize collegiality and coordination, beginning with draft proposals developed by lead services in consultation with relevant Directorates-General via inter-service consultations (ISCs). These ISCs, formalized in the Commission's Rules of Procedure, allow other services a limited window—typically two to three weeks—to provide input, amendments, or objections, fostering horizontal alignment before escalation to political levels.[66] Commissioners' private offices, known as cabinets, exert steering influence by reviewing refined drafts, advising on political priorities, and bridging administrative preparations with the College of Commissioners' final adoption, where decisions require majority support among the 27 members.[67] For executing delegated powers under EU legislation, comitology committees—comprising representatives from member states—provide oversight through advisory, examination, or regulatory procedures, scrutinizing Commission implementing acts to ensure technical conformity and national interests.[68] This layered approach contributes to extended timelines, with empirical data indicating an average duration of approximately 32 months for ordinary legislative procedures from proposal to adoption during the 2009–2014 period, encompassing internal preparations, ISC iterations, and interinstitutional negotiations.[69] More recent first-reading completions averaged 13 months from July 2019 to December 2022, highlighting variability tied to proposal complexity and consensus requirements.[70]Compensation and Benefits

Salary Scales and Adjustments

Salaries for officials in the European Civil Service are structured by career grade and step within categories such as Administrators (AD, grades 5–16) and Assistants (AST, grades 1–11), with basic monthly pay progressing through periodic increments based on seniority and performance.[71] Entry-level salaries for AD5 administrators typically start at around €5,900, while mid-career AD10 positions begin at approximately €10,950 as of mid-2024, reflecting the higher responsibilities and expertise required.[72] These scales fund operations through the EU budget, derived from member state contributions equivalent to taxpayer revenues.[73] Annual adjustments to salary scales are governed by Staff Regulations and calculated via a formula incorporating the Joint Brussels Wage Index (reflecting public sector wage growth in Belgium), corrections for Brussels-specific living costs, and inter-institutional parity factors, with updates effective from 1 July each year.[74] For the 2023–2024 period, adjustments averaged around 7% across grades due to elevated inflation, raising the AD10 starting salary from €10,212 to €10,950; a subsequent Eurostat report informed a 4.1% increase deferred to December 2024 and 1.2% in April 2025.[72][74] This mechanism aims to maintain purchasing power relative to the Brussels economic basket but has drawn scrutiny for not fully offsetting eurozone-wide disparities.[75] EU officials are exempt from national income taxes in their home or host countries, paying instead a progressive community tax (rates from 8% to 45%) deducted at source, which preserves net pay comparability across nationalities.[76] Eligible staff receive an expatriation allowance of 16% applied to the sum of basic salary, household allowance, and dependent child allowance, provided they are not nationals of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, or the Netherlands and have resided elsewhere for prior years.[77] This supplement, funded similarly by the EU budget, compensates for relocation costs but applies only to a subset of staff.[78]| Grade | Entry Step Basic Salary (Monthly, €, as of July 2024) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AD5 | ~5,900 | Typical junior administrator entry[79] |

| AD10 | ~10,950 | Mid-senior level[72] |

| AST3 | ~3,700 | Assistant roles[76] |