Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

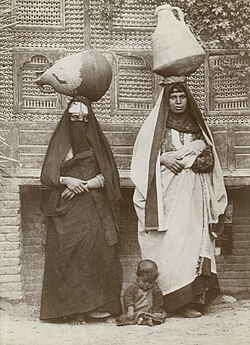

Fellah

View on WikipediaThis article possibly contains original research. (March 2019) |

A fellah (Arabic: فَلَّاح fallāḥ; feminine فَلَّاحَة fallāḥa; plural fellaheen or fellahin, فلاحين, fallāḥīn) is a local farmer, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller".

Due to a continuity in beliefs and lifestyle with that of the Ancient Egyptians, the fellahin of Egypt have been described as the "true" Egyptians.[1]

Origins and usage

[edit]

"Fellahin", throughout the Middle East in the Islamic periods, referred to native villagers and farmers.[2] It is translated as "peasants" or "farmers".[3][4] Fellahin were distinguished from the effendi (land-owning class),[5] although the fellahin in this region might be tenant farmers, smallholders, or live in a village that owned the land communally.[6][7] Others applied the term fellahin only to landless workers.[8]

In Egypt

[edit]

The Fellahin are rural villagers indigenous to Egypt, whose agricultural methods may have contributed to the rise of Ancient Egypt. The Fellahin are mostly Muslims who live in the Nile Valley.[9]

After the Muslim conquest, the rulers called the common masses of indigenous farmers fellahin because their ancient work of agriculture and connecting to their lands was different from the Jews who were traders and the Byzantine Greeks, who were the ruling class. With the passage of time, the name took on an ethnic character, and the Arab elites to some extent used the term fellah synonymously with "indigenous Egyptian". And when a Christian Egyptian (copt or qibt) converted to Islam, he was called falih which means "winner" or "victorious".[3][better source needed]

The Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge, wrote with regards to the Egyptian fellah: "...no amount of alien blood has so far succeeded in destroying the fundamental characteristics, both physical and mental, of the 'dweller of the Nile mud,' i.e. the fellah, or tiller of the ground who is today what he has ever been."[10] He would rephrase stating, "the physical type of the Egyptian fellah is exactly what it was in the earliest dynasties. The Babylonians, Hyksos, Ethiopians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and Turks, have had no permanent effect either on their physical or mental characteristics."[11]

The percentage of fellahin in Egypt was much higher than it is now in the early 20th century, before large numbers migrated into urban towns and cities. In 1927, anthropologist Winifred Blackman, author of The Fellahin of Upper Egypt, conducted ethnographic research on the life of Upper Egyptian farmers and concluded that there were observable continuities between the cultural and religious beliefs and practices of the fellahin and those of ancient Egyptians.[12][better source needed]

In 2003, the fellahin were still leading humble lives and living in their houses, like their ancient ancestors.[1] In 2005, they comprised some 60 percent of the total Egyptian population.[13]

In the Levant

[edit]In the Levant, specifically in Palestine, Jordan and Hauran, the term fellahin was used to refer to the majority of the countryside.[14] The term fallah was also applied to native people from several regions in the North Africa and the Middle East, also including those of Cyprus.[citation needed]

In Dobruja

[edit]During the nineteenth century, some Muslim Fellah families from Ottoman Syria settled in Dobruja, a region now divided between Bulgaria and Romania, then part of the Ottoman Empire. They fully intermingled with the Turks and Tatars, and were Turkified.[15]

Gallery

[edit]-

Fellahin using a traditional agricultural plow

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pateman, Robert & Salwa El-Hamamsy (2003). Egypt. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. p. 54. ISBN 9780761416708.

The fellahin have been described as the 'true' Egyptians.

- ^ Mahdi, Kamil A.; Würth, Anna; Lackner, Helen (2007). Yemen Into the Twenty-First Century: Continuity and Change. Garnet & Ithaca Press. p. 209. ISBN 9780863722905.

- ^ a b "Fellahin - Fallahin - Falih - Aflah'", maajim.com, maajam dictionary

- ^ Masalha, Nur (2005). Catastrophe Remembered: Palestine, Israel and the Internal Refugees: Essays in Memory of Edward W. Said (1935–2003). Zed Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-84277-623-0.

- ^ Warwick P. N. Tyler, State Lands and Rural Development in mandatory Palestine, 1920–1948, Sussex Academic Press, 2001, p. 13

- ^ Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917–1948, University of California Press, 2008, p. 32

- ^ Sandra Marlene Sufian, Healing the Land and the Nation: Malaria and the Zionist Project in Palestine, 1920–1947, University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 57

- ^ Michael Gilsenan, Lords of the Lebanese Marches: Violence and Narrative in an Arab Society, I. B. Tauris, 1996, p. 13

- ^ Fellahin also known as "Egyptians (Rural)"

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

- ^ Budge, Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis (1910). The Nile: Notes for Travellers in Egypt and in the Egyptian Sûdân. T. Cook & son (Egypt), Limited. p. 143.

- ^ Faraldi, Caryll (11–17 May 2000). "A genius for hobnobbing". Al-Ahram Weekly. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Who Are the Fellahin?" Biot #312: December 24, 2005. SEMP, Inc.

- ^ Smith, George Adam (1918). Syria and the Holy Land. George H. Doran company. p. 41.

fellahin syria.

- ^ Grigore, George. "George Grigore. "Muslims in Romania", ISIM Newsletter (International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World) no. 3, Leiden. 1999: 34".

External links

[edit]Fellah

View on GrokipediaA fellah (Arabic: فَلَّاح, fallāḥ; plural fellaheen or fellahin, فَلَّاحِين, fallāḥīn) denotes a peasant farmer or agricultural laborer in Arab countries, most prominently in Egypt, where this social class has historically dominated rural life through intensive cultivation of Nile Valley soils.[1][2] Derived from the Arabic root falaha, signifying "to plow" or "till the soil," the term underscores their foundational role in subsistence agriculture, employing rudimentary tools and irrigation to maximize yields from limited fertile land amid arid surroundings.[3][4]

The fellaheen represent indigenous rural villagers, often regarded as perpetuating some of the world's most ancient farming practices, with communities clustered in villages dependent on the Nile's seasonal floods for crop cycles of wheat, barley, and cotton.[2] Economically vital yet socially stratified below urban elites and landowners, they have endured cycles of poverty, heavy taxation, and land tenure systems that prioritized extraction over investment, fostering resilience through communal labor and traditional knowledge.[5][6] Defining characteristics include their adaptive husbandry of water-scarce environments, where meticulous field preparation and crop rotation sustain populations, though modernization efforts in the 20th century gradually shifted some toward mechanized farming and urban migration.[7]