Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shape

View on Wikipedia

A shape is a graphical representation of an object's form or its external boundary, outline, or external surface. It is distinct from other object properties, such as color, texture, or material type. In geometry, shape excludes information about the object's position, size, orientation and chirality.[1] A figure is a representation including both shape and size (as in, e.g., figure of the Earth).

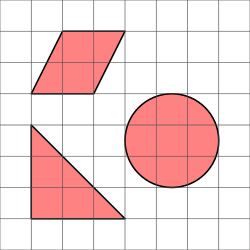

A plane shape or plane figure is constrained to lie on a plane, in contrast to solid 3D shapes. A two-dimensional shape or two-dimensional figure (also: 2D shape or 2D figure) may lie on a more general curved surface (a two-dimensional space).

Classification of simple shapes

[edit]

Some simple shapes can be put into broad categories. For instance, polygons are classified according to their number of edges as triangles, quadrilaterals, pentagons, etc. Each of these is divided into smaller categories; triangles can be equilateral, isosceles, obtuse, acute, scalene, etc. while quadrilaterals can be rectangles, rhombi, trapezoids, squares, etc.

Other common shapes are points, lines, planes, and conic sections such as ellipses, circles, and parabolas.

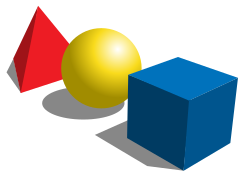

Among the most common three-dimensional shapes are polyhedra, which are shapes with flat faces; ellipsoids, which are egg-shaped or sphere-shaped objects; cylinders; and cones.

If an object falls into one of these categories exactly or even approximately, we can use it to describe the shape of the object. Thus, we say that the shape of a manhole cover is a disk, because it is approximately the same geometric object as an actual geometric disk.

In geometry

[edit]

A geometric shape consists of the geometric information which remains when location, scale, orientation and reflection are removed from the description of a geometric object.[1] That is, the result of moving a shape around, enlarging it, rotating it, or reflecting it in a mirror is the same shape as the original, and not a distinct shape.

Many two-dimensional geometric shapes can be defined by a set of points or vertices and lines connecting the points in a closed chain, as well as the resulting interior points. Such shapes are called polygons and include triangles, squares, and pentagons. Other shapes may be bounded by curves such as the circle or the ellipse.

Many three-dimensional geometric shapes can be defined by a set of vertices, lines connecting the vertices, and two-dimensional faces enclosed by those lines, as well as the resulting interior points. Such shapes are called polyhedrons and include cubes as well as pyramids such as tetrahedrons. Other three-dimensional shapes may be bounded by curved surfaces, such as the ellipsoid and the sphere.

A shape is said to be convex if all of the points on a line segment between any two of its points are also part of the shape.

Properties

[edit]There are multiple ways to compare the shapes of two objects:

- Congruence: Two objects are congruent if one can be transformed into the other by a sequence of rotations, translations, and/or reflections.

- Similarity: Two objects are similar if one can be transformed into the other by a uniform scaling, together with a sequence of rotations, translations, and/or reflections.

- Isotopy: Two objects are isotopic if one can be transformed into the other by a sequence of deformations that do not tear the object or put holes in it.

Sometimes, two similar or congruent objects may be regarded as having a different shape if a reflection is required to transform one into the other. For instance, the letters "b" and "d" are a reflection of each other, and hence they are congruent and similar, but in some contexts they are not regarded as having the same shape. Sometimes, only the outline or external boundary of the object is considered to determine its shape. For instance, a hollow sphere may be considered to have the same shape as a solid sphere. Procrustes analysis is used in many sciences to determine whether or not two objects have the same shape, or to measure the difference between two shapes. In advanced mathematics, quasi-isometry can be used as a criterion to state that two shapes are approximately the same.

Simple shapes can often be classified into basic geometric objects such as a line, a curve, a plane, a plane figure (e.g. square or circle), or a solid figure (e.g. cube or sphere). However, most shapes occurring in the physical world are complex. Some, such as plant structures and coastlines, may be so complicated as to defy traditional mathematical description – in which case they may be analyzed by differential geometry, or as fractals.

Some common shapes include: Circle, Square, Triangle, Rectangle, Oval, Star (polygon), Rhombus, Semicircle. Regular polygons starting at pentagon follow the naming convention of the Greek derived prefix with '-gon' suffix: Pentagon, Hexagon, Heptagon, Octagon, Nonagon, Decagon... See polygon

Equivalence of shapes

[edit]In geometry, two subsets of a Euclidean space have the same shape if one can be transformed to the other by a combination of translations, rotations (together also called rigid transformations), and uniform scalings. In other words, the shape of a set of points is all the geometrical information that is invariant to translations, rotations, and size changes. Having the same shape is an equivalence relation, and accordingly a precise mathematical definition of the notion of shape can be given as being an equivalence class of subsets of a Euclidean space having the same shape.

Mathematician and statistician David George Kendall writes:[2]

In this paper ‘shape’ is used in the vulgar sense, and means what one would normally expect it to mean. [...] We here define ‘shape’ informally as ‘all the geometrical information that remains when location, scale[3] and rotational effects are filtered out from an object.’

Shapes of physical objects are equal if the subsets of space these objects occupy satisfy the definition above. In particular, the shape does not depend on the size and placement in space of the object. For instance, a "d" and a "p" have the same shape, as they can be perfectly superimposed if the "d" is translated to the right by a given distance, rotated upside down and magnified by a given factor (see Procrustes superimposition for details). However, a mirror image could be called a different shape. For instance, a "b" and a "p" have a different shape, at least when they are constrained to move within a two-dimensional space like the page on which they are written. Even though they have the same size, there's no way to perfectly superimpose them by translating and rotating them along the page. Similarly, within a three-dimensional space, a right hand and a left hand have a different shape, even if they are the mirror images of each other. Shapes may change if the object is scaled non-uniformly. For example, a sphere becomes an ellipsoid when scaled differently in the vertical and horizontal directions. In other words, preserving axes of symmetry (if they exist) is important for preserving shapes. Also, shape is determined by only the outer boundary of an object.

Congruence and similarity

[edit]Objects that can be transformed into each other by rigid transformations and mirroring (but not scaling) are congruent. An object is therefore congruent to its mirror image (even if it is not symmetric), but not to a scaled version. Two congruent objects always have either the same shape or mirror image shapes, and have the same size.

Objects that have the same shape or mirror image shapes are called geometrically similar, whether or not they have the same size. Thus, objects that can be transformed into each other by rigid transformations, mirroring, and uniform scaling are similar. Similarity is preserved when one of the objects is uniformly scaled, while congruence is not. Thus, congruent objects are always geometrically similar, but similar objects may not be congruent, as they may have different size.

Homeomorphism

[edit]A more flexible definition of shape takes into consideration the fact that realistic shapes are often deformable, e.g. a person in different postures, a tree bending in the wind or a hand with different finger positions.

One way of modeling non-rigid movements is by homeomorphisms. Roughly speaking, a homeomorphism is a continuous stretching and bending of an object into a new shape. Thus, a square and a circle are homeomorphic to each other, but a sphere and a donut are not. An often-repeated mathematical joke is that topologists cannot tell their coffee cup from their donut,[4] since a sufficiently pliable donut could be reshaped to the form of a coffee cup by creating a dimple and progressively enlarging it, while preserving the donut hole in a cup's handle.

A described shape has external lines that you can see and make up the shape. If you were putting your coordinates on a coordinate graph you could draw lines to show where you can see a shape, however not every time you put coordinates in a graph as such you can make a shape. This shape has a outline and boundary so you can see it and is not just regular dots on a regular paper.

Shape analysis

[edit]The above-mentioned mathematical definitions of rigid and non-rigid shape have arisen in the field of statistical shape analysis. In particular, Procrustes analysis is a technique used for comparing shapes of similar objects (e.g. bones of different animals), or measuring the deformation of a deformable object. Other methods are designed to work with non-rigid (bendable) objects, e.g. for posture independent shape retrieval (see for example Spectral shape analysis).

Similarity classes

[edit]All similar triangles have the same shape. These shapes can be classified using complex numbers u, v, w for the vertices, in a method advanced by J.A. Lester[5] and Rafael Artzy. For example, an equilateral triangle can be expressed by the complex numbers 0, 1, (1 + i√3)/2 representing its vertices. Lester and Artzy call the ratio the shape of triangle (u, v, w). Then the shape of the equilateral triangle is For any affine transformation of the complex plane, a triangle is transformed but does not change its shape. Hence shape is an invariant of affine geometry. The shape p = S(u,v,w) depends on the order of the arguments of function S, but permutations lead to related values. For instance, Also Combining these permutations gives Furthermore, These relations are "conversion rules" for shape of a triangle.

The shape of a quadrilateral is associated with two complex numbers p, q. If the quadrilateral has vertices u, v, w, x, then p = S(u,v,w) and q = S(v,w,x). Artzy proves these propositions about quadrilateral shapes:

- If then the quadrilateral is a parallelogram.

- If a parallelogram has | arg p | = | arg q |, then it is a rhombus.

- When p = 1 + i and q = (1 + i)/2, then the quadrilateral is square.

- If and sgn r = sgn(Im p), then the quadrilateral is a trapezoid.

A polygon has a shape defined by n − 2 complex numbers The polygon bounds a convex set when all these shape components have imaginary components of the same sign.[6]

Human perception of shapes

[edit]Human vision relies on a wide range of shape representations.[7][8] Some psychologists have theorized that humans mentally break down images into simple geometric shapes (e.g., cones and spheres) called geons.[9] Meanwhile, others have suggested shapes are decomposed into features or dimensions that describe the way shapes tend to vary, like their segmentability, compactness and spikiness.[10] When comparing shape similarity, however, at least 22 independent dimensions are needed to account for the way natural shapes vary.[7]

There is also clear evidence that shapes guide human attention.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kendall, D.G. (1984). "Shape Manifolds, Procrustean Metrics, and Complex Projective Spaces". Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society. 16 (2): 81–121. doi:10.1112/blms/16.2.81.

- ^ Kendall, D.G. (1984). "Shape Manifolds, Procrustean Metrics, and Complex Projective Spaces" (PDF). Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society. 16 (2): 81–121. doi:10.1112/blms/16.2.81.

- ^ Here, scale means only uniform scaling, as non-uniform scaling would change the shape of the object (e.g., it would turn a square into a rectangle).

- ^ Hubbard, John H.; West, Beverly H. (1995). Differential Equations: A Dynamical Systems Approach. Part II: Higher-Dimensional Systems. Texts in Applied Mathematics. Vol. 18. Springer. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-387-94377-0.

- ^ J.A. Lester (1996) "Triangles I: Shapes", Aequationes Mathematicae 52:30–54

- ^ Rafael Artzy (1994) "Shapes of Polygons", Journal of Geometry 50(1–2):11–15

- ^ a b Morgenstern, Yaniv; Hartmann, Frieder; Schmidt, Filipp; Tiedemann, Henning; Prokott, Eugen; Maiello, Guido; Fleming, Roland (2021). "An image-computable model of visual shape similarity". PLOS Computational Biology. 17 (6): 34. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008981. PMC 8195351. PMID 34061825.

- ^ Andreopoulos, Alexander; Tsotsos, John K. (2013). "50 Years of object recognition: Directions forward". Computer Vision and Image Understanding. 117 (8): 827–891. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2013.04.005.

- ^ Marr, D., & Nishihara, H. (1978). Representation and recognition of the spatial organization of three-dimensional shapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 200, 269–294.

- ^ Huang, Liqiang (2020). "Space of preattentive shape features". Journal of Vision. 20 (4): 10. doi:10.1167/jov.20.4.10. PMC 7405702. PMID 32315405.

- ^ Alexander, R. G.; Schmidt, J.; Zelinsky, G.Z. (2014). "Are summary statistics enough? Evidence for the importance of shape in guiding visual search". Visual Cognition. 22 (3–4): 595–609. doi:10.1080/13506285.2014.890989. PMC 4500174. PMID 26180505.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of shape at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of shape at Wiktionary

Shape

View on GrokipediaFundamental Concepts

Definition and Scope

In geometry, shape refers to the two-dimensional or three-dimensional contour or silhouette of an object, abstracted from its size, position, orientation, and reflections, capturing the essential geometric configuration invariant under similarity transformations.[9] This abstraction distinguishes shape from mere form by emphasizing the relational arrangement of points, lines, or surfaces that define an object's boundary or structure.[10] The term "shape" originates from the Old English word scēap, meaning "creation," "creature," or "form," derived from the Proto-Germanic skapiz, which connoted fashioning or external configuration.[11] Early philosophical discussions of ideal shapes appear in Plato's Timaeus, where he posits that the classical elements—fire, air, water, and earth—are composed of perfect geometric polyhedra: tetrahedra for fire, octahedra for air, icosahedra for water, and cubes for earth, representing eternal, unchanging archetypes in the realm of Forms.[12] In mathematics, shapes are formally regarded as subsets of Euclidean space , encompassing both their boundaries and interiors, often with smooth or piecewise linear structures to model real-world contours.[13] For instance, a circle in the plane is the set of all points equidistant from a fixed center point, defined by the equation for radius . Similarly, a polygon is a closed figure formed by a finite chain of connected line segments, such as a triangle with three sides or a quadrilateral with four. These examples illustrate how shapes provide a foundational framework for analyzing spatial relations in geometry.Distinction from Related Terms

In art and design, shape refers to the geometric essence or intrinsic configuration of an object, independent of its material composition, whereas form often denotes the physical manifestation, including aspects like texture, material, and three-dimensional volume.[14] For instance, while a geometric shape captures the abstract boundary and proportions of a circle, its form would encompass how it appears when constructed from clay or metal, emphasizing depth and solidity.[15] This distinction highlights shape as a primarily two-dimensional attribute, excluding tangible properties that form introduces. In mathematics, "shape" and "figure" are often used interchangeably to describe geometric entities, though "figure" may sometimes refer to a specific representation incorporating size and position, while "shape" emphasizes the essential type or class abstracted from such details.[16] An outline, by contrast, pertains solely to the boundary or perimeter of a shape, neglecting the interior structure or filled area that defines the full geometric entity.[17] In biology, shape constitutes one component of morphology, which broadly examines the overall structure, size, and organization of organisms, integrating shape with functional and evolutionary aspects.[18] Similarly, in art, shape is confined to two-dimensional contours, distinct from mass, which represents three-dimensional volume and weight implied by solid forms. In physics, shape describes the fixed geometric profile of a single object, while configuration refers to the variable arrangement of multiple parts or particles within a system, as explored in configuration space. A common misconception is that shape inherently includes size; however, in geometry, shapes are scale-invariant, meaning objects of different sizes but identical proportions—such as a small circle and a large circle—share the same shape, with size addressed separately through concepts like congruence or similarity.[19]Classification of Shapes

Basic Geometric Shapes

Basic geometric shapes serve as the foundational elements in geometry, providing the building blocks for constructing more complex figures in both two and three dimensions. These shapes are characterized by their boundaries and internal structures, with two-dimensional shapes lying in a plane and three-dimensional shapes occupying space. In two dimensions, polygons form a primary category of shapes, defined as closed figures bounded by a finite number of straight line segments known as sides. A triangle is a polygon with exactly three sides, a quadrilateral with four sides, and a pentagon with five sides.[20] Polygons are further classified as regular or irregular: a regular polygon has all sides of equal length and all interior angles equal, while an irregular polygon lacks this uniformity in sides or angles.[21] Curved two-dimensional shapes include the circle, which is the set of all points in a plane equidistant from a fixed point called the center, and the ellipse, defined as the set of all points in a plane such that the sum of the distances to two fixed points (the foci) remains constant.[22][23] Three-dimensional shapes, or solids, extend these concepts into space, with polyhedra representing the polygonal analogs. A polyhedron is a solid figure bounded by flat polygonal faces, where edges are the line segments formed by the intersection of two faces, and vertices are the points where three or more edges meet.[24] Common polyhedra include the cube, a regular hexahedron with six square faces, twelve edges, and eight vertices; prisms, which feature two parallel polygonal bases connected by rectangular lateral faces; and pyramids, consisting of a polygonal base and triangular lateral faces that meet at a single apex point.[25][26] Curved three-dimensional shapes encompass the sphere, the set of all points in space equidistant from a fixed center point, and the cylinder, formed by two parallel circular bases joined by a curved lateral surface generated by straight lines perpendicular to the bases.[27][28] Within polyhedra, the Platonic solids stand out as the most symmetric regular polyhedra, where all faces are congruent regular polygons and an identical number of faces meet at each vertex. The five Platonic solids are the tetrahedron (4 equilateral triangular faces, 6 edges, 4 vertices), cube (6 square faces, 12 edges, 8 vertices), octahedron (8 equilateral triangular faces, 12 edges, 6 vertices), dodecahedron (12 regular pentagonal faces, 30 edges, 20 vertices), and icosahedron (20 equilateral triangular faces, 30 edges, 12 vertices). These solids possess exceptional symmetry, characterized by their rotation groups: the tetrahedral group (order 12) for the tetrahedron, the octahedral group (order 24) for the cube and octahedron, and the icosahedral group (order 60) for the dodecahedron and icosahedron.[29] A fundamental property relating the components of polyhedra is Euler's formula, which asserts that for any convex polyhedron, the number of vertices , edges , and faces satisfies the equation This relation, first articulated by Leonhard Euler in his 1752 paper "Elementa doctrinae solidorum," provides a topological invariant that holds for all such shapes and can be verified for the Platonic solids—for instance, the cube yields .[30]Advanced and Composite Shapes

Composite shapes are formed by applying Boolean operations—such as union, intersection, and difference—to basic geometric primitives like spheres, cylinders, or polyhedra, enabling the construction of more intricate forms in computational geometry and solid modeling.[31] The union operation combines the volumes of multiple primitives into a single entity, retaining all areas occupied by at least one shape; intersection yields the overlapping region shared by all involved primitives; and difference subtracts the volume of subsequent primitives from the first, creating voids or cutouts.[31] These operations, foundational to constructive solid geometry (CSG), allow for hierarchical modeling where complex objects are built recursively from simpler ones, as implemented in early computer-aided design systems.[31] A prominent example of composite shapes using intersections and unions is the Venn diagram, which visualizes set relationships through overlapping circles or other closed curves. Introduced by John Venn in 1880, these diagrams represent the union of sets as the encompassing area and intersections as shared regions, facilitating logical reasoning about categorical propositions. Star polygons, another class of composites, arise from connecting vertices of a regular polygon in a non-adjacent sequence, forming self-intersecting figures like the pentagram.[32] Denoted by the Schläfli symbol {p/q}, where p is the number of vertices and q the step size (with p and q coprime), the pentagram corresponds to {5/2}, illustrating density and winding in polygonal construction.[32] This notation, developed by Ludwig Schläfli in 1852, extends to describe regular star polyhedra and higher forms.[32] Non-Euclidean shapes deviate from flat Euclidean space, incorporating curvature that alters fundamental properties like parallel lines and triangle sums. Hyperbolic geometry, pioneered by Nikolai Lobachevsky in his 1829 work On the Principles of Geometry, features spaces where multiple parallels can pass through a point not on a given line, resulting in exponential area growth for circles and ideal polygons with infinite sides.[33] Spherical geometry, formalized by Bernhard Riemann in 1854, models positive curvature on a sphere's surface, where parallels converge, triangles exceed 180 degrees in sum, and geodesics (great circles) form the shortest paths. These geometries underpin modern relativity and cosmology, contrasting Euclidean assumptions. Fractals represent a subset of non-Euclidean shapes characterized by self-similarity, where patterns repeat at every scale, yielding non-integer dimensions that quantify irregularity.[34] The Mandelbrot set, defined by the iterative equation for complex c, produces boundaries with infinite detail and self-similar motifs, as explored by Benoit Mandelbrot in 1980.[34] Self-similarity dimension, for strictly self-similar fractals, is computed as , where N is the number of copies scaled by factor s; this often equals the Hausdorff dimension for sets like the Sierpinski gasket (d ≈ 1.585).[35] Mandelbrot's 1982 book The Fractal Geometry of Nature formalized fractals as sets with Hausdorff dimension greater than topological dimension but less than embedding space, capturing natural roughness.[34] Higher-dimensional analogs extend three-dimensional shapes into four or more dimensions, challenging visualization but describable via projections. The tesseract, or four-dimensional hypercube, possesses 8 cubic cells, 24 square faces, 32 edges, and 16 vertices, analogous to how a cube has 6 faces from a square. Coined by Charles Howard Hinton in 1888, it can be projected onto three-dimensional space as two nested cubes connected by truncated pyramids, rotating to reveal its hypervolume of 1 unit in four dimensions. Such projections, detailed in Hinton's A New Era of Thought (1900), aid intuition for hyperspheres and polytopes in n-dimensions. Mathematical examples of advanced shapes include non-orientable surfaces, which lack consistent "inside" and "outside." The Möbius strip, independently discovered by August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing in 1858, is formed by twisting a rectangular strip 180 degrees and joining ends, resulting in a one-sided surface with a single boundary edge.[36] Traversing its length returns to the starting point with reversed orientation, demonstrating non-orientability.[36] The Klein bottle, described by Felix Klein in 1882, embeds in four-dimensional space as a tube intersecting itself without boundary, generalizing the Möbius strip to a closed surface of Euler characteristic 0.[37] In three dimensions, it self-intersects, but in higher space, it remains immersion-free, exemplifying projective plane properties.[37]Properties in Geometry

Intrinsic Properties

In geometry, intrinsic properties of shapes are characteristics that depend solely on the internal structure of the shape itself, independent of its position, orientation, or embedding in a larger space. These properties remain invariant under rigid transformations, such as translations, rotations, and reflections, which preserve distances and angles. For instance, on a surface, intrinsic properties can be measured entirely from within the surface without reference to the surrounding ambient space.[38] A fundamental intrinsic property for two-dimensional regions is the area, which quantifies the extent enclosed by the boundary and is computed as the double integral over the region: . Similarly, the perimeter or boundary length for a closed curve is an intrinsic measure given by the line integral along the boundary, where is the arc length element. These measures are preserved under isometries, as they rely only on the metric induced by the shape. For polygonal shapes, the sum of interior angles provides another intrinsic invariant: for an -gon, this sum equals radians, reflecting the topological and metric consistency of the polygon's interior.[39][40] For curves, the arc length is a core intrinsic property, defined for a curve parameterized by as , which captures the total length independent of the curve's placement in space. This formula arises from approximating the curve with infinitesimal straight segments and integrating their lengths, ensuring invariance under reparameterization or rigid motion. On surfaces, intrinsic geometry is richly described by curvature invariants; notably, the Gaussian curvature at a point, given in local coordinates by where and are coefficients of the first and second fundamental forms, respectively, measures the intrinsic bending of the surface. This property, proven invariant under local isometries by Gauss's Theorema Egregium in 1827, distinguishes surfaces up to their internal metric structure—for example, a sphere's positive Gaussian curvature cannot be flattened without distortion. The mean curvature, while related, is extrinsic and thus not invariant in the same way, but Gaussian curvature alone suffices to encode essential intrinsic differences.[41][42][43] These intrinsic properties underpin congruence relations, where two shapes are congruent if there exists a rigid transformation mapping one to the other while preserving all such measures. Examples include the fixed area of a disk under rotation or the unchanging arc length of a helix when rigidly transformed, highlighting how intrinsic traits define a shape's essential form.[44]Extrinsic Properties

Extrinsic properties of shapes are those that depend on the specific embedding of the shape within a coordinate system or ambient space, rather than solely on the shape's internal structure. For instance, the position of the centroid, defined as the average location of all points weighted by mass or area, varies with the chosen origin and axes of the coordinate system. This reliance on external coordinates distinguishes extrinsic properties from intrinsic ones, such as area, which remain unchanged under rigid transformations.[38][45] Key extrinsic properties include bounding box dimensions, moments of inertia, and orientation angles. The bounding box, often an axis-aligned rectangle or box that encloses the shape, has dimensions that change with the shape's rotation relative to the coordinate axes, providing a measure of spatial extent sensitive to embedding. Moments of inertia quantify the distribution of mass or area relative to specific axes; for example, the moment about the x-axis is calculated aswhere is the perpendicular distance from the axis and is the differential mass element—this value depends on the orientation of the axes chosen. Orientation angles, such as the angle of rotation in the plane or Euler angles in three dimensions, directly describe how the shape is aligned within the space, altering under rotations.[46][47] Such properties become particularly relevant in physics applications, where center of mass calculations for irregular shapes rely on extrinsic coordinates to determine stability and dynamics—for example, integrating position vectors over the shape's mass distribution to find the center of mass point.