Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Square

View on Wikipedia

| Square | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Edges and vertices | 4 |

| Symmetry group | order-8 dihedral |

| Area | side2 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | π/2 (90°) |

| Perimeter | 4 · side |

In geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral. It has four straight sides of equal length and four equal angles. Squares are special cases of rectangles, which have four equal angles, and of rhombuses, which have four equal sides. As with all rectangles, a square's angles are right angles (90 degrees, or π/2 radians), making adjacent sides perpendicular. The area of a square is the side length multiplied by itself, and so in algebra, multiplying a number by itself is called squaring.

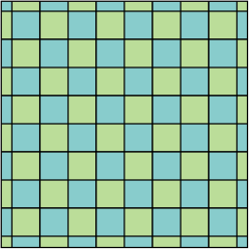

Equal squares can tile the plane edge-to-edge in the square tiling. Square tilings are ubiquitous in tiled floors and walls, graph paper, image pixels, and game boards. Square shapes are also often seen in building floor plans, origami paper, food servings, in graphic design and heraldry, and in instant photos and fine art.

The formula for the area of a square forms the basis of the calculation of area and motivates the search for methods for squaring the circle by compass and straightedge, now known to be impossible. Squares can be inscribed in any smooth or convex curve, such as a circle or triangle, but it remains unsolved whether a square can be inscribed in every simple closed curve. Several problems of squaring the square involve subdividing squares into unequal squares. Mathematicians have also studied packing squares as tightly as possible into other shapes.

Squares can be constructed by straightedge and compass, through their Cartesian coordinates, or by repeated multiplication by in the complex plane. They form the metric balls for taxicab geometry and Chebyshev distance, two forms of non-Euclidean geometry. Although spherical geometry and hyperbolic geometry both lack polygons with four equal sides and right angles, they have square-like regular polygons with four sides and other angles, or with right angles and different numbers of sides.

Definitions and characterizations

[edit]

Squares can be defined or characterized in many equivalent ways. If a polygon in the Euclidean plane satisfies any one of the following criteria, it satisfies all of them:

- A square is a polygon with four equal sides and four right angles; that is, it is a quadrilateral that is both a rhombus and a rectangle[1]

- A square is a rectangle with four equal sides.[1]

- A square is a rhombus with a right angle between a pair of adjacent sides.[1]

- A square is a rhombus with all angles equal.[1]

- A square is a parallelogram with one right angle and two adjacent equal sides.[1]

- A square is a quadrilateral where the diagonals are equal, and are the perpendicular bisectors of each other. That is, it is a rhombus with equal diagonals.[2]

- A square is a quadrilateral with successive sides , , , whose area is[3]

Squares are the only regular polygons whose internal angle, central angle, and external angle are all equal (they are all right angles).[4]

Properties

[edit]A square is a special case of a rhombus (equal sides, opposite equal angles), a kite (two pairs of adjacent equal sides), a trapezoid (one pair of opposite sides parallel), a parallelogram (all opposite sides parallel), a quadrilateral or tetragon (four-sided polygon), and a rectangle (opposite sides equal, right-angles),[1] and therefore has all the properties of all these shapes, namely:

- All four internal angles of a square are equal (each being 90°, a right angle).[4][5]

- The central angle of a square is equal to 90°.[4]

- The external angle of a square is equal to 90°.[4]

- The diagonals of a square are equal and bisect each other, meeting at 90°.[5]

- The diagonals of a square bisect its internal angles, forming adjacent angles of 45°.[6]

- All four sides of a square are equal.[7]

- Opposite sides of a square are parallel.[8]

All squares are similar to each other, meaning they have the same shape.[9] One parameter (typically the length of a side or diagonal)[10] suffices to specify a square's size. Squares of the same size are congruent.[11]

Measurement

[edit]

A square whose four sides have length has perimeter[12] and diagonal length .[13] The square root of 2, appearing in this formula, is irrational, meaning that it cannot be written exactly as a fraction. It is approximately equal to 1.414,[14] and its approximate value was already known in Babylonian mathematics.[15] A square's area is[13] This formula for the area of a square as the second power of its side length led to the use of the term squaring to mean raising any number to the second power.[16] Reversing this relation, the side length of a square of a given area is the square root of the area. Squaring an integer, or taking the area of a square with integer sides, results in a square number; these are figurate numbers representing the numbers of points that can be arranged into a square grid.[17]

Since four squared equals sixteen, a four by four square has an area equal to its perimeter. That is, it is an equable shape. The only other equable integer rectangle is a three-by-six rectangle.[18]

Because it is a regular polygon, a square is the quadrilateral of least perimeter enclosing a given area. Dually, a square is the quadrilateral containing the largest area within a given perimeter.[19] Indeed, if A and P are the area and perimeter enclosed by a quadrilateral, then the following isoperimetric inequality holds: with equality if and only if the quadrilateral is a square.[20][21]

Symmetry

[edit]The square is the most symmetrical of the quadrilaterals.[22] Eight rigid transformations of the plane take the square to itself:[23]

(the identity transformation)

For an axis-parallel square centered at the origin, each symmetry acts by a combination of negating and swapping the Cartesian coordinates of points.[24] The symmetries permute the eight isosceles triangles between the half-edges and the square's center (which stays in place); any of these triangles can be taken as the fundamental region of the transformations.[25] Each two vertices, each two edges, and each two half-edges are mapped one to the other by at least one symmetry (exactly one for half-edges).[22] All regular polygons also have these properties,[26] which are expressed by saying that symmetries of a square and, more generally, a regular polygon act transitively on vertices and edges, and simply transitively on half-edges.[27]

Combining any two of these transformations by performing one after the other continues to take the square to itself, and therefore produces another symmetry. Repeated rotation produces another rotation with the summed rotation angle. Two reflections with the same axis return to the identity transformation, while two reflections with different axes rotate the square. A rotation followed by a reflection, or vice versa, produces a different reflection. This composition operation gives the eight symmetries of a square the mathematical structure of a group, called the group of the square or the dihedral group of order eight.[23] Other quadrilaterals, like the rectangle and rhombus, have only a subgroup of these symmetries.[28][29]

The shape of a square, but not its size, is preserved by similarities of the plane.[30] Other kinds of transformations of the plane can take squares to other kinds of quadrilateral. An affine transformation can take a square to any parallelogram, or vice versa;[31] a projective transformation can take a square to any convex quadrilateral, or vice versa.[32] This implies that, when viewed in perspective, a square can look like any convex quadrilateral, or vice versa.[33] A Möbius transformation can take the vertices of a square (but not its edges) to the vertices of a harmonic quadrilateral.[34]

The wallpaper groups are symmetry groups of two-dimensional repeating patterns. For many of these groups the basic unit of repetition (the unit cell of its period lattice) can be a square, and for three of these groups, p4, p4m, and p4g, it must be a square.[35]

Inscribed and circumscribed circles

[edit]

The inscribed circle of a square is the largest circle that can fit inside that square. Its center is the center point of the square, and its radius (the inradius of the square) is . Because this circle touches all four sides of the square (at their midpoints), the square is a tangential quadrilateral. The circumscribed circle of a square passes through all four vertices, making the square a cyclic quadrilateral. Its radius, the circumradius, is .[36] If the inscribed circle of a square has tangency points on , on , on , and on , then for any point on the inscribed circle,[37] If is the distance from an arbitrary point in the plane to the th vertex of a square and is the circumradius of the square, then[38] If and are the distances from an arbitrary point in the plane to the centroid of the square and its four vertices respectively, then and where is the circumradius of the square.[39]

Applications

[edit]Squares are so well-established as the shape of tiles that the Latin word tessera, for a small tile as used in mosaics, comes from an ancient Greek word for the number four, referring to the four corners of a square tile.[40] Graph paper, preprinted with a square tiling, is widely used for data visualization using Cartesian coordinates.[41] The pixels of bitmap images, as recorded by image scanners and digital cameras or displayed on electronic visual displays, conventionally lie at the intersections of a square grid, and are often considered as small squares, arranged in a square tiling.[42][43] Standard techniques for image compression and video compression, including the JPEG format, are based on the subdivision of images into larger square blocks of pixels.[44] The quadtree data structure used in data compression and computational geometry is based on the recursive subdivision of squares into smaller squares.[45]

Architectural structures from both ancient and modern cultures have featured a square floor plan, base, or footprint. Ancient examples include the Egyptian pyramids,[46] Mesoamerican pyramids such as those at Teotihuacan,[47] the Chogha Zanbil ziggurat in Iran,[48] the four-fold design of Persian walled gardens, said to model the four rivers of Paradise, and later structures inspired by their design such as the Taj Mahal in India,[49] the square bases of Buddhist stupas,[50] and East Asian pagodas, buildings that symbolically face to the four points of the compass and reach to the heavens.[51] Norman keeps such as the Tower of London often take the form of a low square tower.[52] In modern architecture, a majority of skyscrapers feature a square plan for pragmatic rather than aesthetic or symbolic reasons.[53]

The stylized nested squares of a Tibetan mandala, like the design of a stupa, function as a miniature model of the cosmos.[54] Some formats for film photography use a square aspect ratio, notably Polaroid cameras, medium format cameras, and Instamatic cameras.[55][56] Painters known for their frequent and prominent use of square forms and frames include Josef Albers,[57] Kazimir Malevich[58] Piet Mondrian,[59] and Theo van Doesburg.[60]

Baseball diamonds[61] and boxing rings are square despite being named for other shapes.[62] In the quadrille and square dance, four couples form the sides of a square.[63] In Samuel Beckett's minimalist television play Quad, four actors walk along the sides and diagonals of a square.[64]

The square go board is said to represent the earth, with the 361 crossings of its lines representing days of the year.[65] The chessboard inherited its square shape from a pachisi-like Indian race game and in turn passed it on to checkers.[66] In two ancient games from Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, the Royal Game of Ur and Senet, the game board itself is not square, but rectangular, subdivided into a grid of squares.[67] The ancient Greek Ostomachion puzzle (according to some interpretations) involves rearranging the pieces of a square cut into smaller polygons, as does the Chinese tangram.[68] Another set of puzzle pieces, the polyominos, are formed from squares glued edge-to-edge.[69] Medieval and Renaissance horoscopes were arranged in a square format, across Europe, the Middle East, and China.[70] Other recreational uses of squares include the shape of origami paper,[71] and a common style of quilting involving the use of square quilt blocks.[72] Scrabble players place square lettered tiles[73] onto a grid of squares on a square board.[74]

Squares are a common element of graphic design, used to give a sense of stability, symmetry, and order.[75] In heraldry, a canton (a design element in the top left of a shield) is normally square, and a square flag is called a banner.[76] The flag of Switzerland is square, as are the flags of the Swiss cantons.[77] QR codes are square and feature prominent nested square alignment marks in three corners.[78] Robertson screws have a square drive socket.[79] Crackers and sliced cheese are often square,[80] as are waffles.[81][82] Square foods named for their square shapes include caramel squares, date squares, lemon squares,[83] square sausage,[84] and Carré de l'Est cheese.[85]

In stereochemistry, a square planar molecular geometry is a chemical structure with atoms at the corners of a square. An example is xenon tetrafluoride.[86]

Constructions

[edit]Coordinates and equations

[edit]

A unit square is a square of side length one. Often it is represented in Cartesian coordinates as the square enclosing the points that have and . Its vertices are the four points that have 0 or 1 in each of their coordinates.[87]

An axis-parallel square with its center at the point and sides of length (where is the inradius, half the side length) has vertices at the four points . Its interior consists of the points with , and its boundary consists of the points with .[88]

A diagonal square with its center at the point and diagonal of length (where is the circumradius, half the diagonal) has vertices at the four points and . Its interior consists of the points with , and its boundary consists of the points with .[88] For instance the illustration shows a diagonal square centered at the origin with circumradius 2, given by the equation .

In the plane of complex numbers, multiplication by the imaginary unit rotates the other term in the product by 90° around the origin (the number zero). Therefore, if any nonzero complex number is repeatedly multiplied by , giving the four numbers , , , and , these numbers will form the vertices of a square centered at the origin.[89] If one interprets the real part and imaginary part of these four complex numbers as Cartesian coordinates, with , then these four numbers have the coordinates , , , and .[90] This square can be translated to have any other complex number is center, using the fact that the translation from the origin to is represented in complex number arithmetic as addition with .[91] The Gaussian integers, complex numbers with integer real and imaginary parts, form a square lattice in the complex plane.[91]

Compass and straightedge

[edit]The construction of a square with a given side, using a compass and straightedge, is given in Euclid's Elements I.46.[92] The existence of this construction means that squares are constructible polygons. A regular -gon is constructible exactly when the odd prime factors of are distinct Fermat primes,[93] and in the case of a square has no odd prime factors so this condition is vacuously true.[94]

Elements IV.6–7 also give constructions for a square inscribed in a circle and circumscribed about a circle, respectively.[95]

-

Square with a given circumcircle

-

Square with a given side length, using Thales' theorem

-

Square with a given diagonal

Related topics

[edit]The Schläfli symbol of a square is {4}.[96] A truncated square is an octagon.[97] The square belongs to a family of regular polytopes that includes the cube in three dimensions and the hypercubes in higher dimensions,[98] and to another family that includes the regular octahedron in three dimensions and the cross-polytopes in higher dimensions.[99] The cube and hypercubes can be given vertex coordinates that are all , giving an axis-parallel square in two dimensions, while the octahedron and cross-polytopes have one coordinate and the rest zero, giving a diagonal square in two dimensions.[100] As with squares, the symmetries of these shapes can be obtained by applying a signed permutation to their coordinates.[24]

The Sierpiński carpet is a square fractal, with square holes.[101] Space-filling curves including the Hilbert curve, Peano curve, and Sierpiński curve cover a square as the continuous image of a line segment.[102] The Z-order curve is analogous but not continuous.[103] Other mathematical functions associated with squares include Arnold's cat map and the baker's map, which generate chaotic dynamical systems on a square,[104] and the lemniscate elliptic functions, complex functions periodic on a square grid.[105]

The Finsler–Hadwiger theorem states that for two squares and , the center of both squares and the midpoint of and form a third square. This theorem can be applied repeatedly to prove van Aubel's theorem, that the centers of four squares constructed on the sides of a quadrilateral form a midsquare quadrilateral.[106] A square cannot be dissected into an odd number of equal-area triangles, a result of Monsky's theorem.[107]

Mathematical puzzles that include squares are square arrays that are filled with numbers in Sudoku[108] with generalized symbols in Latin square,[109] and with color or blank in nonogram,[110] as well as paradoxical optical illusions such as the missing square puzzle[111] and the chessboard paradox.[112]

Inscribed squares

[edit]

A square is inscribed in a curve when all four vertices of the square lie on the curve. The unsolved inscribed square problem asks whether every simple closed curve has an inscribed square. It is true for every smooth curve,[114] and for any closed convex curve. The only other regular polygon that can always be inscribed in every closed convex curve is the equilateral triangle, as there exists a convex curve on which no other regular polygon can be inscribed.[115]

For an inscribed square in a triangle, at least one side of the square lies on a side of the triangle. Every acute triangle has three inscribed squares, one for each of its three sides. A right triangle has two inscribed squares, one touching its right angle and the other lying on its hypotenuse. An obtuse triangle has only one inscribed square, on its longest side. A square inscribed in a triangle can cover at most half the triangle's area.[116]

Area and quadrature

[edit]

Since ancient times, many units for surface area have been defined from squares, typically with a standard unit of length as its side, for example a square meter or square inch.[117]

In ancient Greek deductive geometry, the area of a planar shape was measured and compared by constructing a square with the same area by using only a finite number of steps with compass and straightedge, a process called quadrature or squaring. Euclid's Elements shows how to do this for rectangles, parallelograms, triangles, and then more generally for simple polygons by breaking them into triangular pieces.[118] Some shapes with curved sides could also be squared, such as the lune of Hippocrates[119] and the parabola.[120]

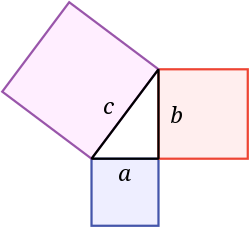

This use of a square as the defining shape for area measurement also occurs in the Greek formulation of the Pythagorean theorem: squares constructed on the two sides of a right triangle have equal total area to a square constructed on the hypotenuse.[121] Stated in this form, the theorem would be equally valid for other shapes on the sides of the triangle, such as equilateral triangles or semicircles,[122] but the Greeks used squares. In modern mathematics, this formulation of the theorem using areas of squares has been replaced by an algebraic formulation involving squaring numbers: the lengths of the sides and hypotenuse of the right triangle obey the equation .[123]

Because of this focus on quadrature as a measure of area, the Greeks and later mathematicians sought unsuccessfully to square the circle, constructing a square with the same area as a given circle, again using finitely many steps with a compass and straightedge. In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible as a consequence of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem. This theorem proves that pi (π) is a transcendental number rather than an algebraic irrational number; that is, it is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients. A construction for squaring the circle could be translated into a polynomial formula for π, which does not exist.[124] In philosophy, the concept of a "square circle" has been used as an example of an oxymoron since Aristotle, sparking attempts to find contexts such as taxicab geometry (below) in which this phrase is meaningful.[125]

Tiling and packing

[edit]The square tiling, familiar from flooring and game boards, is one of three regular tilings of the plane. The other two use the equilateral triangle and the regular hexagon.[126] The vertices of a square tiling form a square lattice.[127] Squares of more than one size can also tile the plane,[128][129] for instance in the Pythagorean tiling, named for its connection to proofs of the Pythagorean theorem.[130]

Square packing problems seek the smallest square or circle into which a given number of unit squares can fit. A chessboard optimally packs a square number of unit squares into a larger square, but beyond a few special cases such as this, the optimal solutions to these problems remain unsolved;[131][132][133] the same is true for circle packing in a square.[134] Packing squares into other shapes can have high computational complexity: testing whether a given number of unit squares can fit into an orthogonally convex rectilinear polygon with half-integer vertex coordinates is NP-complete.[135]

Squaring the square involves subdividing a given square into smaller squares, all having integer side lengths. A subdivision with distinct smaller squares is called a perfect squared square.[136] Another variant of squaring the square called "Mrs. Perkins's quilt" allows repetitions, but uses as few smaller squares as possible in order to make the greatest common divisor of the side lengths be 1.[137] The entire plane can be tiled by squares, with exactly one square of each integer side length.[138]

In higher dimensions, other surfaces than the plane can be tiled by equal squares, meeting edge-to-edge. One of these surfaces is the Clifford torus, the four-dimensional Cartesian product of two congruent circles; it has the same intrinsic geometry as a single square with each pair of opposite edges glued together.[139] Another square-tiled surface, a regular skew apeirohedron in three dimensions, has six squares meeting at each vertex.[140] The paper bag problem seeks the maximum volume that can be enclosed by a surface tiled with two squares glued edge to edge; its exact answer is unknown.[141] Gluing two squares in a different pattern, with the vertex of each square attached to the midpoint of an edge of the other square (or alternatively subdividing these two squares into eight squares glued edge-to-edge) produces a pincushion shape called a biscornu.[142] The surfaces tiled with finitely many squares of the three-dimensional integer lattice are called polyominoids.[143]

Counting

[edit]

A common mathematical puzzle involves counting the squares of all sizes in a square grid of squares. For instance, a square grid of nine squares has 14 squares: the nine squares that form the grid, four more squares, and one square. The answer to the puzzle is , a square pyramidal number.[144] For these numbers are:[145]

A variant of the same puzzle asks for the number of squares formed by a grid of points, allowing squares that are not axis-parallel. For instance, a grid of nine points has five axis-parallel squares as described above, but it also contains one more diagonal square for a total of six.[146] In this case, the answer is given by the 4-dimensional pyramidal numbers . For these numbers are:[147]

Another counting problem involving squares asks for the number of different shapes of rectangles that can be used when dividing a square into similar rectangles. A square can be divided into two similar rectangles only in one way, by bisecting it, but when dividing a square into three similar rectangles there are three possible aspect ratios of the rectangles,[148] 3:1, 3:2, and the square of the plastic ratio, approximately 1.755:1.[149] The number of proportions that are possible when dividing into rectangles is known for small values of , but not as a general formula. For these numbers are:[150]

A magic square is a square array of numbers, where the sums of the positive numbers in each row, each column, and both main diagonals are the same.[151] For array, the sum can be formulated as ; the numbers for are:[152]

Other geometries

[edit]In the familiar Euclidean geometry, space is flat, and every convex quadrilateral has internal angles summing to 360°, so a square (a regular quadrilateral) has four equal sides and four right angles (each 90°). By contrast, in spherical geometry and hyperbolic geometry, space is curved and the internal angles of a convex quadrilateral never sum to 360°, so quadrilaterals with four right angles do not exist. Both of these geometries feature regular quadrilaterals, characterized by four equal sides and four equal angles, often referred to as squares,[153] although some authors prefer to avoid this name because they lack right angles. These geometries also feature regular polygons with right angles, but with the number of sides differing from four.[154]

In spherical geometry, space has uniform positive curvature, and every convex quadrilateral (a polygon with four great-circle arc edges) has angles whose sum exceeds 360° by an amount called the angular excess, proportional to its surface area. Small spherical squares are approximately Euclidean, and the angles of larger squares increase with area.[153] One special case is the face of a spherical cube with four 120° angles, covering one sixth of the sphere's surface.[155] Another is a hemisphere, the face of a spherical square dihedron, with four straight angles; the Peirce quincuncial projection for world maps conformally maps two such faces to Euclidean squares.[156] An octant of a sphere is a regular spherical triangle, with three equal sides and three right angles; eight of them tile the sphere, with four meeting at each vertex, to form a spherical octahedron.[157] A spherical lune is a regular digon, with two semicircular sides and two equal angles at antipodal vertices; a right-angled lune covers one quarter of the sphere, one face of a four-lune hosohedron.[158]

In hyperbolic geometry, space has uniform negative curvature, and every convex quadrilateral has angles whose sum falls short of 360° by an amount called the angular defect, proportional to its surface area. Small hyperbolic squares are approximately Euclidean, and larger squares decrease with increasing area. Special cases include the squares with angles of 360°/n for every value of n larger than 4, each of which can tile the hyperbolic plane.[154] In the infinite limit, an ideal square has four sides of infinite length and four vertices at ideal points outside the hyperbolic plane, with 0° internal angles;[159] an ideal square, like every ideal quadrilateral, has finite area proportional to its angular defect of 360°.[160] It is also possible to make a regular hyperbolic polygon with right angles at every vertex and any number of sides greater than four; such polygons can uniformly tile the hyperbolic plane, dual to the tiling with n squares about each vertex.[154]

The Euclidean plane can be defined in terms of the real coordinate plane by adoption of the Euclidean distance function, according to which the distance between any two points and is . Other metric geometries are formed when a different distance function is adopted instead, and in some of these geometries, shapes that would be Euclidean squares become the "circles" (set of points of equal distance from a center point). Squares tilted at 45° to the coordinate axes are the circles in taxicab geometry, based on the distance . The points with taxicab distance from any given point form a diagonal square, centered at the given point, with diagonal length . In the same way, axis-parallel squares are the circles for the or Chebyshev distance, . In this metric, the points with distance from some point form an axis-parallel square, centered at the given point, with side length .[161][162][163]

See also

[edit]- Minkowski–Bouligand dimension, a way of determining the fractal dimension of a set by covering the number of squares.

- Square trisection, a problem of cutting and reassembling one square into three squares

- Squircle, a shape intermediate between a square and a circle

- Tarski's circle-squaring problem, dividing a disk into sets that can be rearranged into a square

- Thébault's theorem, on squares placed on the sides of a quadrilateral

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Usiskin, Zalman; Griffin, Jennifer (2008). The Classification of Quadrilaterals: A Study of Definition. Information Age Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-59311-695-8.

- ^ Wilson, Jim (Summer 2010). "Problem Set 1.3, problem 10". Math 5200/7200 Foundations of Geometry I. University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 2022-11-27. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2020). "Theorem 9.2.1". A Cornucopia of Quadrilaterals. Dolciani Mathematical Expositions. Vol. 55. American Mathematical Society. p. 186. ISBN 9781470453121.

- ^ a b c d Rich, Barnett (1963). Principles And Problems Of Plane Geometry. Schaum. p. 132.

- ^ a b Godfrey, Charles; Siddons, A. W. (1919). Elementary Geometry: Practical and Theoretical (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 40.

- ^ Schorling, R.; Clark, John P.; Carter, H. W. (1935). Modern Mathematics: An Elementary Course. George G. Harrap & Co. pp. 124–125.

- ^ Godfrey & Siddons (1919), p. 135.

- ^ Schorling, Clark & Carter (1935), p. 101.

- ^ Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Project Mathematics! Program Guide and Workbook: Similarity. California Institute of Technology. p. 8–9. Workbook accompanying Project Mathematics! Ep. 1: "Similarity" (Video).

- ^ Gellert, W.; Gottwald, S.; Hellwich, M.; Kästner, H.; Küstner, H. (1989). "Quadrilaterals". The VNR Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. § 7.5, p. 161. ISBN 0-442-20590-2.

- ^ Henrici, Olaus (1879). Elementary Geometry: Congruent Figures. Longmans, Green. p. 134.

- ^ Rich (1963), p. 131.

- ^ a b Rich (1963), p. 120.

- ^ Conway, J. H.; Guy, R. K. (1996). The Book of Numbers. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 181–183.

- ^ Fowler, David; Robson, Eleanor (1998). "Square root approximations in old Babylonian mathematics: YBC 7289 in context". Historia Mathematica. 25 (4): 366–378. doi:10.1006/hmat.1998.2209. MR 1662496.

- ^ Thomson, James (1845). An Elementary Treatise on Algebra: Theoretical and Practical. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 4.

- ^ Conway & Guy (1996), pp. 30–33, 38–40.

- ^ Konhauser, Joseph D. E.; Velleman, Dan; Wagon, Stan (1997). "95. When does the perimeter equal the area?". Which Way Did the Bicycle Go?: And Other Intriguing Mathematical Mysteries. Dolciani Mathematical Expositions. Vol. 18. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780883853252.

- ^ Page 147 of Chakerian, G. D. (1979). "A distorted view of geometry". In Honsberger, Ross (ed.). Mathematical Plums. The Dolciani Mathematical Expositions. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. pp. 130–150. ISBN 0-88385-304-3. MR 0563059.

- ^ Fink, A. M. (November 2014). "98.30 The isoperimetric inequality for quadrilaterals". The Mathematical Gazette. 98 (543): 504. doi:10.1017/S0025557200008275. JSTOR 24496543.

- ^ Alsina & Nelsen (2020), p. 187, Theorem 9.2.2.

- ^ a b Berger, Marcel (2010). Geometry Revealed: A Jacob's Ladder to Modern Higher Geometry. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 509. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70997-8. ISBN 978-3-540-70996-1. MR 2724440.

- ^ a b Miller, G. A. (1903). "On the groups of the figures of elementary geometry". The American Mathematical Monthly. 10 (10): 215–218. doi:10.1080/00029890.1903.11997111. JSTOR 2969176. MR 1515975.

- ^ a b Estévez, Manuel; Roldán, Érika; Segerman, Henry (2023). "Surfaces in the tesseract". In Holdener, Judy; Torrence, Eve; Fong, Chamberlain; Seaton, Katherine (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2023: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Culture. Phoenix, Arizona: Tessellations Publishing. pp. 441–444. arXiv:2311.06596. ISBN 978-1-938664-45-8.

- ^ Grove, L. C.; Benson, C. T. (1985). Finite Reflection Groups. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 99 (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 9. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-1869-0. ISBN 0-387-96082-1. MR 0777684.

- ^ Toth, Gabor (2002). "Section 9: Symmetries of regular polygons". Glimpses of Algebra and Geometry. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (Second ed.). Springer-Verlag, New York. pp. 96–106. doi:10.1007/0-387-22455-6_9. ISBN 0-387-95345-0. MR 1901214.

- ^ Davis, Michael W. (2008). The Geometry and Topology of Coxeter Groups. London Mathematical Society Monographs Series. Vol. 32. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-691-13138-2. MR 2360474.

- ^ Conway, John H.; Burgiel, Heidi; Goodman-Strauss, Chaim (2008). "Figure 20.3". The Symmetries of Things. AK Peters. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5.

- ^ Beardon, Alan F. (2012). "What is the most symmetric quadrilateral?". The Mathematical Gazette. 96 (536): 207–212. doi:10.1017/S0025557200004435. JSTOR 23248552.

- ^ Frost, Janet Hart; Dornoo, Michael D.; Wiest, Lynda R. (November 2006). "Take time for action: Similar shapes and ratios". Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School. 12 (4): 222–224. doi:10.5951/MTMS.12.4.0222. JSTOR 41182391.

- ^ Gerber, Leon (1980). "Napoleon's theorem and the parallelogram inequality for affine-regular polygons". The American Mathematical Monthly. 87 (8): 644–648. doi:10.1080/00029890.1980.11995110. JSTOR 2320952. MR 0600923.

- ^ Wylie, C. R. (1970). Introduction to Projective Geometry. McGraw-Hill. pp. 17–19. Reprinted, Dover Books, 2008, ISBN 9780486468952

- ^ Francis, George K. (1987). A Topological Picturebook. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 52. ISBN 0-387-96426-6. MR 0880519.

- ^ Johnson, Roger A. (2007) [1929]. Advanced Euclidean Geometry. Dover. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0.

- ^ Schattschneider, Doris (1978). "The plane symmetry groups: their recognition and notation". The American Mathematical Monthly. 85 (6): 439–450. doi:10.1080/00029890.1978.11994612. JSTOR 2320063. MR 0477980.

- ^ Rich (1963), p. 133.

- ^ Gutierrez, Antonio. "Problem 331. Discovering the Relationship between Distances from a Point on the Inscribed Circle to Tangency Point and Vertices in a Square". Go Geometry from the Land of the Incas. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Park, Poo-Sung (2016). "Regular polytopic distances" (PDF). Forum Geometricorum. 16: 227–232. MR 3507218. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-10.

- ^ Meskhishvili, Mamuka (2021). "Cyclic averages of regular polygonal distances" (PDF). International Journal of Geometry. 10 (1): 58–65. MR 4193377.

- ^ Garg, Anu. "Tessera". A word a day. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ Cox, D. R. (1978). "Some Remarks on the Role in Statistics of Graphical Methods". Applied Statistics. 27 (1): 4–9. doi:10.2307/2346220. JSTOR 2346220.

- ^ Salomon, David (2011). The Computer Graphics Manual. Springer. p. 30. ISBN 9780857298867.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (1995). A Pixel Is Not A Little Square, A Pixel Is Not A Little Square, A Pixel Is Not A Little Square! (And a Voxel is Not a Little Cube) (PDF) (Technical report). Microsoft. Microsoft Computer Graphics, Technical Memo 6.

- ^ Richardson, Iain E. (2002). Video Codec Design: Developing Image and Video Compression Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 127. ISBN 9780471485537.

- ^ Samet, Hanan (2006). "1.4 Quadtrees". Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures. Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 28–48. ISBN 9780123694461.

- ^ Vafea, Flora (2002). "The mathematics of pyramid construction in ancient Egypt". Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 2 (1): 111–125.

- ^ Sugiyama, Saburo (June 1993). "Worldview materialized in Teotihuacan, Mexico". Latin American Antiquity. 4 (2): 103–129. doi:10.2307/971798. JSTOR 971798.

- ^ Ghirshman, Roman (January 1961). "The Ziggurat of Tchoga-Zanbil". Scientific American. 204 (1): 68–77. Bibcode:1961SciAm.204a..68G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0161-68. JSTOR 24940741.

- ^ Stiny, G; Mitchell, W J (1980). "The grammar of paradise: on the generation of Mughul gardens" (PDF). Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 7 (2): 209–226. Bibcode:1980EnPlB...7..209S. doi:10.1068/b070209.

- ^ Nakamura, Yuuka; Okazaki, Shigeyuki (2016). "The Spatial Composition of Buddhist Temples in Central Asia, Part 1: The Transformation of Stupas" (PDF). International Understanding. 6: 31–43.

- ^ Guo, Qinghua (2004). "From tower to pagoda: structural and technological transition". Construction History. 20: 3–19. JSTOR 41613875.

- ^ Bruce, J. Collingwood (October 1850). "On the structure of the Norman Fortress in England". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 6 (3). Informa UK Limited: 209–228. doi:10.1080/00681288.1850.11886925. See p. 213.

- ^ Choi, Yongsun (2000). A Study on Planning and Development of Tall Building: The Exploration of Planning Considerations (Ph.D. thesis). Illinois Institute of Technology. ProQuest 304600838. See in particular pp. 88–90

- ^ Xu, Ping (Fall 2010). "The mandala as a cosmic model used to systematically structure the Tibetan Buddhist landscape". Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. 27 (3): 181–203. JSTOR 43030905.

- ^ Chester, Alicia (September 2018). "The outmoded instant: From Instagram to Polaroid". Afterimage. 45 (5). University of California Press: 10–15. doi:10.1525/aft.2018.45.5.10.

- ^ Adams, Ansel (1980). "Medium-Format Cameras". The Camera. Boston: New York Graphic Society. Ch. 3, pp. 21–28.

- ^ Mai, James (2016). "Planes and frames: spatial layering in Josef Albers' Homage to the Square paintings". In Torrence, Eve; Torrence, Bruce; Séquin, Carlo; McKenna, Douglas; Fenyvesi, Kristóf; Sarhangi, Reza (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2016: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Education, Culture. Phoenix, Arizona: Tessellations Publishing. pp. 233–240. ISBN 978-1-938664-19-9.

- ^ Luecking, Stephen (June 2010). "A man and his square: Kasimir Malevich and the visualization of the fourth dimension". Journal of Mathematics and the Arts. 4 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1080/17513471003744395.

- ^ Millard, Charles W. (Summer 1972). "Mondrian". The Hudson Review. 25 (2): 270–274. doi:10.2307/3849001. JSTOR 3849001.

- ^ Pimm, David (July 2001). "Some notes on Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) and His Arithmetic Composition 1" (PDF). For the Learning of Mathematics. 21: 31–36. JSTOR 40248360.

- ^ Battista, Michael T. (April 1993). "Mathematics in Baseball". The Mathematics Teacher. 86 (4): 336–342. doi:10.5951/mt.86.4.0336. JSTOR 27968332. See p. 339.

- ^ Chetwynd, Josh (2016). The Field Guide to Sports Metaphors: A Compendium of Competitive Words and Idioms. Ten Speed Press. p. 122. ISBN 9781607748113.

The decision to go oxymoron with a squared "ring" had taken place by the late 1830s ... Despite the geometric shift, the language was set.

- ^ Sciarappa, Luke; Henle, Jim (2022). "Square Dance from a Mathematical Perspective". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 44 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1007/s00283-021-10151-0. PMC 8889875. PMID 35250151.

- ^ Worthen, William B. (2010). "Quad: Euclidean Dramaturgies" (PDF). Drama: Between Poetry and Performance. Wiley. Ch. 4.i, pp. 196–204. ISBN 978-1-405-15342-3.

- ^ Lang, Ye; Liangzhi, Zhu (2024). "Weiqi: A Game of Wits". Insights into Chinese Culture. Springer Nature Singapore. pp. 469–476. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-4511-1_38. ISBN 9789819745111. See page 472.

- ^ Newman, James R. (August 1961). "About the rich lore of games played on boards and tables (review of Board and Table Games From Many Civilizations by R. C. Bell)". Scientific American. 205 (2): 155–161. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0861-155. JSTOR 24937045.

- ^ Donovan, Tristan (2017). It's All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. St. Martin's. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9781250082725.

- ^ Klarreich, Erica (May 15, 2004). "Glimpses of Genius: mathematicians and historians piece together a puzzle that Archimedes pondered". Science News: 314–315. doi:10.2307/4015223. JSTOR 4015223.

- ^ Golomb, Solomon W. (1994). Polyominoes: Puzzles, Patterns, Problems, and Packings (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08573-0. MR 1291821.

- ^ Thomann, Johannes (2008). "Chapter Five: Square Horoscope Diagrams In Middle Eastern Astrology And Chinese Cosmological Diagrams: Were These Designs Transmitted Through The Silk Road?". In Forêt, Philippe; Kaplony, Andreas (eds.). The Journey of Maps and Images on the Silk Road. Brill's Inner Asian Library. Vol. 21. BRILL. pp. 97–118. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004171657.i-248.45. ISBN 9789004171657.

- ^ Cipra, Barry A. "In the Fold: Origami Meets Mathematics" (PDF). SIAM News. 34 (8).

- ^ Wickstrom, Megan H. (November 2014). "Piecing it together". Teaching Children Mathematics. 21 (4): 220–227. doi:10.5951/teacchilmath.21.4.0220. JSTOR 10.5951/teacchilmath.21.4.0220.

- ^ Edley, Joe; Williams, John (2009). Everything Scrabble (3rd ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. xxii. ISBN 9781416561750.

- ^ Hart, Melissa (2006). A Guide for Using Kira-Kira in the Classroom. Teacher Created Resources. p. 23. ISBN 9781420630039.

- ^ Nyamweya, Jeff (2024). Everything Graphic Design: A Comprehensive Understanding of Visual Communications for Beginners & Creatives. Bogano. p. 78. ISBN 9789914371413.

- ^ Boutell, Charles (1864). Heraldry, Historical and Popular (2nd ed.). London: Bentley. p. 31, 89.

- ^ Complete Flags of the World: The Ultimate Pocket Guide (7th ed.). DK Penguin Random House. 2021. pp. 200–206. ISBN 978-0-7440-6001-0.

- ^ Kan, Tai-Wei; Teng, Chin-Hung; Chen, Mike Y. (2011). "QR code based augmented reality applications". In Furht, Borko (ed.). Handbook of Augmented Reality. Springer. pp. 339–354. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0064-6_16. ISBN 9781461400646. See especially Section 2.1, Appearance, pp. 341–342.

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (2000). One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw. Scribner. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-0-684-86730-4.

- ^ Charlesworth, Rosalind; Lind, Karen (1990). Math and Science for Young Children. Delmar Publishers. p. 195. ISBN 9780827334021.

- ^ Yanagihara, Dawn (2014). Waffles: Sweet, Savory, Simple. Chronicle Books. p. 11. ISBN 9781452138411.

- ^ Kraig, Bruce; Sen, Colleen Taylor (2013). Street Food around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 50. ISBN 9781598849554.

- ^ Jesperson, Ivan F. (1989). Fat-Back and Molasses. Breakwater Books. ISBN 9780920502044. Caramel squares and date squares, p. 134; lemon squares, p. 104.

- ^ Allen, Gary (2015). Sausage: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 57. ISBN 9781780235554.

- ^ Harbutt, Juliet (2015). World Cheese Book. Penguin. p. 45. ISBN 9781465443724.

- ^ Gillespie, Ronald J.; Hargittai, Istvan (2012). The VSEPR Model of Molecular Geometry. Dover Publications. p. 156. ISBN 9780486486154.

- ^ Rosenthal, Daniel; Rosenthal, David; Rosenthal, Peter (2018). A Readable Introduction to Real Mathematics. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (2nd ed.). Springer International Publishing. p. 108. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-00632-7. ISBN 9783030006327.

- ^ a b Iobst, Christopher Simon (14 June 2018). "Shapes and Their Equations: Experimentation with Desmos". Ohio Journal of School Mathematics. 79 (1): 27–31. doi:10.18061/ojsm.4113.

- ^ Vince, John (2011). Rotation Transforms for Computer Graphics. London: Springer. p. 11. Bibcode:2011rtfc.book.....V. doi:10.1007/978-0-85729-154-7. ISBN 9780857291547.

- ^ Nahin, Paul (2010). An Imaginary Tale: The Story of . Princeton University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781400833894.

- ^ a b McLeman, Cam; McNicholas, Erin; Starr, Colin (2022). Explorations in Number Theory: Commuting through the Numberverse. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer International Publishing. p. 7. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-98931-6. ISBN 9783030989316.

- ^ Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 46. Online English version by David E. Joyce.

- ^ Martin, George E. (1998). Geometric Constructions. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, New York. p. 46. ISBN 0-387-98276-0.

- ^ Sethuraman, B. A. (1997). Rings, Fields, and Vector Spaces: An Introduction to Abstract Algebra via Geometric Constructibility. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag. p. 183. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2700-5. ISBN 0-387-94848-1. MR 1476915.

- ^ Euclid's Elements, Book IV, Proposition 6, Proposition 7. Online English version by David E. Joyce.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1948). Regular Polytopes. Methuen and Co. p. 2.

- ^ Coxeter (1948), p. 148.

- ^ Coxeter (1948), pp. 122–123.

- ^ Coxeter (1948), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Coxeter (1948), pp. 122, 126.

- ^ Barker, William; Howe, Roger (2007). Continuous Symmetry: From Euclid to Klein. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. p. 528. doi:10.1090/mbk/047. ISBN 978-0-8218-3900-3. MR 2362745.

- ^ Sagan, Hans (1994). Space-Filling Curves. Universitext. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0871-6. ISBN 0-387-94265-3. MR 1299533. For the Hilbert curve, see p. 10; for the Peano curve, see p. 35; for the Sierpiński curve, see p. 51.

- ^ Burstedde, Carsten; Holke, Johannes; Isaac, Tobin (2019). "On the number of face-connected components of Morton-type space-filling curves". Foundations of Computational Mathematics. 19 (4): 843–868. arXiv:1505.05055. doi:10.1007/s10208-018-9400-5. MR 3989715.

- ^ Ott, Edward (2002). "7.5 Strongly chaotic systems". Chaos in Dynamical Systems (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 296. ISBN 9781139936576.

- ^ Vlăduț, Serge G. (1991). "2.2 Elliptic functions". Kronecker's Jugendtraum and Modular Functions. Studies in the Development of Modern Mathematics. Vol. 2. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 2-88124-754-7. MR 1121266.

- ^ Alsina & Nelsen (2020), p. 21–23.

- ^ Aigner, Martin; Ziegler, Günter M (2010). "One square and an odd number of triangles". Proofs from The Book (4th ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 131–138. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-00856-6_20. ISBN 9783642008559.

- ^ Hayes, Brian (2017). Foolproof, and Other Mathematical Meditations. MIT Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780262036863.

- ^ Wallis, W. D.; George, J. C. (2011). Introduction to Combinatorics. CRC Press. p. 212. ISBN 9781439806234.

- ^ Demaine, Erik D.; Hearn, Robert A. (2011) [2009]. "Playing games with algorithms: Algorithmic combinatorial game theory". In Albert, Michael H.; Nowakowski, Richard J. (eds.). Games of No Chance 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–56. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511807251. ISBN 9780511807251. See p. 27.

- ^ Singmaster, David (2021). Adventures In Recreational Mathematics: Volume 1. World Scientific. pp. 272–273. ISBN 9789811251627.

- ^ Foster, Colin (2005). "Slippery Slopes". Mathematics in School. 34 (3): 33–34. JSTOR 30215816.

- ^ Conway & Guy (1996), p. 206.

- ^ Matschke, Benjamin (2014). "A survey on the square peg problem". Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 61 (4): 346–352. doi:10.1090/noti1100. hdl:21.11116/0000-0004-15B8-5.

- ^ Eggleston, H. G. (1958). "Figures inscribed in convex sets". The American Mathematical Monthly. 65 (2): 76–80. doi:10.1080/00029890.1958.11989144. JSTOR 2308878. MR 0097768.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (September 1997). "Some surprising theorems about rectangles in triangles". Math Horizons. 5 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1080/10724117.1997.11975023.

- ^ Miller, G. A. (1929). "Graphical methods and the history of mathematics". Tohoku Mathematical Journal. 31: 292–295.

- ^ Euclid's Elements, Book II, Proposition 14. Online English version by David E. Joyce.

- ^ Postnikov, M. M. (2000). "The problem of squarable lunes". The American Mathematical Monthly. 107 (7): 645–651. doi:10.2307/2589121. JSTOR 2589121.

- ^ Berendonk, Stephan (2017). "Ways to square the parabola—a commented picture gallery". Mathematische Semesterberichte. 64 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/s00591-016-0173-0. MR 3629442.

- ^ Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 47. Online English version by David E. Joyce.

- ^ Euclid's Elements, Book VI, Proposition 31. Online English version by David E. Joyce.

- ^ Maor, Eli (2019). The Pythagorean Theorem: A 4,000-Year History. Princeton University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-691-19688-6.

- ^ Kasner, Edward (July 1933). "Squaring the circle". The Scientific Monthly. 37 (1): 67–71. Bibcode:1933SciMo..37...67K. JSTOR 15685.

- ^ Angere, Staffan (January 2017). "The Square Circle". Metaphilosophy. 48 (1–2). Wiley: 79–95. doi:10.1111/meta.12224. JSTOR 26602042.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). "Figure 1.2.1". Tilings and Patterns. W. H. Freeman. p. 21.

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard (1987), p. 29.

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard (1987), pp. 76–78.

- ^ Fisher, Gwen L. (2003). "Quilt Designs Using Non-Edge-to-Edge Tilings by Squares". Meeting Alhambra: ISAMA-BRIDGES Conference Proceedings. pp. 265–272.

- ^ Nelsen, Roger B. (November 2003). "Paintings, plane tilings, and proofs" (PDF). Math Horizons. 11 (2): 5–8. doi:10.1080/10724117.2003.12021741. S2CID 126000048.

- ^ a b Friedman, Erich (2009). "Packing unit squares in squares: a survey and new results". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 1000 DS7: Aug 14. Dynamic Survey 7. doi:10.37236/28. MR 1668055. Archived from the original on 2018-02-24. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ^ Chung, Fan; Graham, Ron (2020). "Efficient packings of unit squares in a large square" (PDF). Discrete & Computational Geometry. 64 (3): 690–699. doi:10.1007/s00454-019-00088-9.

- ^ Montanher, Tiago; Neumaier, Arnold; Markót, Mihály Csaba; Domes, Ferenc; Schichl, Hermann (2019). "Rigorous packing of unit squares into a circle". Journal of Global Optimization. 73 (3): 547–565. doi:10.1007/s10898-018-0711-5. MR 3916193. PMC 6394747. PMID 30880874.

- ^ Croft, Hallard T.; Falconer, Kenneth J.; Guy, Richard K. (1991). "D.1 Packing circles or spreading points in a square". Unsolved Problems in Geometry. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 108–110. ISBN 0-387-97506-3.

- ^ Abrahamsen, Mikkel; Stade, Jack (2024). "Hardness of packing, covering and partitioning simple polygons with unit squares". 65th IEEE Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, FOCS 2024, Chicago, IL, USA, October 27–30, 2024. IEEE. pp. 1355–1371. arXiv:2404.09835. doi:10.1109/FOCS61266.2024.00087. ISBN 979-8-3315-1674-1.

- ^ Duijvestijn, A. J. W. (1978). "Simple perfect squared square of lowest order". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B. 25 (2): 240–243. doi:10.1016/0095-8956(78)90041-2. MR 0511994.

- ^ Trustrum, G. B. (1965). "Mrs Perkins's quilt". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 61 (1): 7–11. Bibcode:1965PCPS...61....7T. doi:10.1017/s0305004100038573. MR 0170831.

- ^ Henle, Frederick V.; Henle, James M. (2008). "Squaring the plane" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 115 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1080/00029890.2008.11920491. JSTOR 27642387. S2CID 26663945.

- ^ Thorpe, John A. (1979). "Chapter 14: Parameterized surfaces, Example 9". Elementary Topics in Differential Geometry. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. New York & Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. p. 113. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-6153-7. ISBN 0-387-90357-7. MR 0528129.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1937). "Regular skew polyhedra in three and four dimension, and their topological analogues". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. Second Series. 43 (1): 33–62. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-43.1.33. MR 1575418. Reprinted in The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays, Dover Publications, 1999, pp. 75–105.

- ^ Pak, Igor; Schlenker, Jean-Marc (2010). "Profiles of inflated surfaces". Journal of Nonlinear Mathematical Physics. 17 (2): 145–157. arXiv:0907.5057. doi:10.1142/S140292511000057X. MR 2679444.

- ^ Seaton, Katherine A. (2021-10-02). "Textile D-forms and D 4d". Journal of Mathematics and the Arts. 15 (3–4): 207–217. arXiv:2103.09649. doi:10.1080/17513472.2021.1991134.

- ^ Mason, John; Roldan, Erika; Rothstein, Skye (2025). "Changing the Topology of Polyominoids Through Rigid Origami" (PDF). In Verhoeff, Tom; Swart, David; Gould, S. Louise; Torrence, Eve; Kaplan, Craig S. (eds.). Bridges 2025 Conference Proceedings. Tessellations Publishing. pp. 503–506. ISBN 9781938664519.

- ^ Duffin, Janet; Patchett, Mary; Adamson, Ann; Simmons, Neil (November 1984). "Old squares new faces". Mathematics in School. 13 (5): 2–4. JSTOR 30216270.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A000330 (Square pyramidal numbers)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ Bright, George W. (May 1978). "Using Tables to Solve Some Geometry Problems". The Arithmetic Teacher. 25 (8). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: 39–43. doi:10.5951/at.25.8.0039. JSTOR 41190469.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A002415 (4-dimensional pyramidal numbers)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ Roberts, Siobhan (February 7, 2023). "The quest to find rectangles in a square". The New York Times.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (November 1996). "A guide to computer dating". Scientific American. Vol. 275, no. 5. pp. 116–118. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1196-116. JSTOR 24993455.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A359146 (Divide a square into n similar rectangles; a(n) is the number of different proportions that are possible)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ Andrews, W. S. (1917). Magic Squares and Cubes (2nd ed.). Open Court Publishing. p. 1.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A006003". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ a b Maraner, Paolo (2010). "A spherical Pythagorean theorem". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 32 (3): 46–50. doi:10.1007/s00283-010-9152-9. MR 2721310. See paragraph about spherical squares, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Singer, David A. (1998). "3.2 Tessellations of the Hyperbolic Plane". Geometry: Plane and Fancy. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, New York. pp. 57–64. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0607-1. ISBN 0-387-98306-6. MR 1490036.

- ^ Popko, Edward S. (2012). Divided Spheres: Geodesics and the Orderly Subdivision of the Sphere. CRC Press. pp. 100–10 1. ISBN 9781466504295.

- ^ Lambers, Martin (2016). "Mappings between sphere, disc, and square". Journal of Computer Graphics Techniques. 5 (2): 1–21.

- ^ Stillwell, John (1992). Geometry of Surfaces. Universitext. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 68. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0929-4. ISBN 0-387-97743-0. MR 1171453.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M.; Tóth, László F. (1963). "The Total Length of the Edges of a Non-Euclidean Polyhedron with Triangular Faces". The Quarterly Journal of Mathematics. 14 (1): 273–284. doi:10.1093/qmath/14.1.273.

- ^ Bonahon, Francis (2009). Low-Dimensional Geometry: From Euclidean Surfaces to Hyperbolic Knots. American Mathematical Society. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-8218-4816-6.

- ^ Martin, Gaven J. (2019). "Random ideal hyperbolic quadrilaterals, the cross ratio distribution and punctured tori". Journal of the London Mathematical Society. 100 (3): 851–870. arXiv:1807.06202. doi:10.1112/jlms.12249.

- ^ Scheid, Francis (May 1961). "Square Circles". The Mathematics Teacher. 54 (5): 307–312. doi:10.5951/mt.54.5.0307. JSTOR 27956386.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (November 1980). "Mathematical Games: Taxicab geometry offers a free ride to a non-Euclidean locale". Scientific American. 243 (5): 18–34. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1280-18. JSTOR 24966450.

- ^ Tao, Terence (2016). Analysis II. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. Vol. 38. Springer. pp. 3–4. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1804-6. ISBN 978-981-10-1804-6. MR 3728290.

Square

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Characterizations

Basic Definition

A square is a regular quadrilateral in Euclidean geometry, characterized by four equal-length sides and four right angles, each measuring 90 degrees.[1][6] This definition establishes the square as both equilateral and equiangular, distinguishing it as a special case among polygons.[6] Unlike a rectangle, which has four right angles but opposite sides of equal length without requiring all sides to be equal, a square mandates uniformity in side lengths.[7] Similarly, a rhombus features four equal sides but does not necessarily have right angles, allowing for non-perpendicular orientations.[8] These distinctions highlight the square's unique balance of equality in both sides and angles. Visually, a square appears as a flat, four-sided figure with straight edges meeting at precise corners, forming a stable and balanced shape often exemplified by a square with side length , where all edges measure .[6] Squares exhibit rotational symmetry as a direct consequence of their equal sides and angles, enabling identical appearance under certain rotations.[6] In terms of geometric transformations, two squares are congruent if their corresponding sides are equal in length, preserving both shape and size through rigid motions like translation or rotation.[9] All squares are similar, sharing identical angles and proportional sides regardless of scale, which underscores their uniform shape across different sizes.[9][10]Etymology and Historical Terminology

The word "square" in the context of geometry derives from the Latin quadratus, meaning "square" or "made square," which is the past participle of quadrare "to square" or "to make square." This Latin term stems from quattuor "four," reflecting the shape's four equal sides and angles, and entered English in the mid-13th century via Old French esquerre or esquarre, originally denoting a tool for measuring right angles before extending to the geometric figure itself.[11] In ancient mathematics, the square was referred to by terms emphasizing its four-angled structure, such as the Greek tetragōnon (τετράγωνον), meaning "four-angled" or "four-cornered," a compound of tetra- "four" and gōnia "angle." Euclid, in his Elements (c. 300 BCE), formalized the square within Book I, defining it in Definition 22 as "that [quadrilateral figure] which is both equilateral and right-angled," and using tetragōnon throughout to distinguish it from other quadrilaterals like the rhombus or oblong. Earlier civilizations also employed square shapes in practical measurements; Babylonian mathematicians around 2000 BCE compiled tables of squares for numbers up to 59 on clay tablets, aiding land surveys and calculations, while Egyptian texts from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 BCE) used squares to compute areas in administrative papyri for agriculture and construction.[12][1][13] Over time, the terminology evolved to encompass broader uses beyond the geometric shape, with "square" functioning as a verb from the 1530s to mean "to make square" or "to adjust to a right angle," and as a noun in algebra from the late 14th century to denote a "square number" or perfect square, such as 16 as the square of 4. Euclid's Elements marked a key milestone by integrating the square into axiomatic geometry, with propositions like I.46 demonstrating its construction on a given line segment, influencing subsequent mathematical nomenclature across cultures.[11][14]Geometric Properties

Sides, Angles, and Diagonals

A square is defined by four sides of equal length, with each pair of adjacent sides perpendicular to one another, forming a closed planar figure.[3] This configuration ensures the boundary consists of straight line segments meeting at right angles, distinguishing the square from other quadrilaterals.[15] The interior angles of a square each measure exactly 90 degrees, resulting from the perpendicular adjacency of its sides.[16] Consequently, the exterior angles, formed by extending one side beyond a vertex, also measure 90 degrees at each vertex, as the sum of an interior and adjacent exterior angle is 180 degrees.[17] The diagonals of a square are line segments connecting non-adjacent vertices, opposite corners of the figure.[2] These diagonals are equal in length and bisect each other at a 90-degree angle, intersecting at the center of the square.[3] Additionally, each diagonal bisects the two angles at the vertices it connects, dividing each 90-degree interior angle into two 45-degree angles, and they function as axes of symmetry for the square's geometric structure.[15]Area, Perimeter, and Diagonal Formulas

The perimeter of a square, which measures the total length around its boundary, is calculated as , where is the length of each side.[6] This formula arises directly from the square's four equal sides. The area of a square, representing the space enclosed within its boundaries, is given by .[6] To derive this, divide the square into two congruent right-angled triangles by drawing one diagonal; each triangle has legs of length serving as base and height, yielding an area of per triangle, for a total area of . The length of a diagonal , connecting two opposite vertices, is .[6] This is obtained by applying the Pythagorean theorem to the right triangle formed by two adjacent sides and the diagonal: The Pythagorean theorem is established as Proposition I.47 in Euclid's Elements.[18] For the unit square with , the perimeter is 4, the area is 1, and the diagonal is . Under uniform scaling by a factor , linear measures such as the perimeter and diagonal scale proportionally by (yielding and ), while the area scales by (yielding ).[6]Symmetry Group

The symmetry group of the square is the dihedral group , a non-abelian group of order 8 that captures all transformations leaving the square invariant. This group consists of four rotations—by , , , and about the square's center—and four reflections across its axes of symmetry: the two diagonals and the two midlines passing through the midpoints of opposite sides.[19][20] These elements can be represented as permutations of the square's vertices or as orthogonal matrices preserving the figure.) All elements of are isometries of the Euclidean plane, meaning they preserve distances between points and angles between lines, ensuring that the square maps rigidly onto itself under each transformation.[21] Rotations maintain orientation, while reflections reverse it, but both types rigidly superimpose the square on its original position. In contrast, the symmetry group of a non-square rectangle is the smaller dihedral group (isomorphic to the Klein four-group), which includes only the identity, a rotation, and reflections over the horizontal and vertical midlines, lacking the rotations and diagonal reflections due to the rectangle's reduced regularity. The structure of highlights the square's high degree of invariance, with relations such as rotations composing additively modulo and reflections satisfying specific conjugation rules with rotations.[20] In group-theoretic terms, a fundamental domain for the action of on the square is a subset that intersects each orbit exactly once; for instance, a right-angled isosceles triangle formed by the center and one vertex serves as such a domain, with area one-eighth of the square, and its images under cover the square without overlap or gap, illustrating how symmetries generate the full object from a minimal representative.[22] This concept underscores the role of in modular constructions and periodic extensions.Relation to Inscribed and Circumscribed Circles

A square admits both an inscribed circle, known as the incircle, and a circumscribed circle, known as the circumcircle. The incircle is tangent to all four sides of the square, with its center at the square's center of symmetry. For a square with side length , the radius of the incircle is , derived directly from the geometry where the diameter equals the side length.[6] The area of the incircle is , which is times the area of the square .[6] The circumcircle passes through all four vertices of the square, also centered at the square's center. Its radius is , obtained by halving the diagonal length , as the diagonal spans the diameter of the circumcircle.[6] Thus, . The area of the circumcircle is , or times the square's area.[6] Among all rectangles inscribed in a fixed circle (sharing the same circumradius), the square achieves the maximum area. This follows from the constraint for length and width , where the area is maximized when , yielding .[23]Constructions

Coordinate and Equation Representations

In analytic geometry, a square of side length is often placed on the coordinate plane with vertices at , , , and , aligning its sides parallel to the coordinate axes.[24] This standard positioning facilitates calculations in Cartesian coordinates and serves as a basis for translations and rotations. For a square centered at with sides parallel to the axes, the boundary equation is given by , corresponding to the unit ball in the norm scaled appropriately.[6] The interior region satisfies . This representation highlights the square's equivalence to a rotated and scaled diamond in other norms, but emphasizes its axis-aligned form here. Squares rotated by an angle relative to the axes can be described using transformed coordinates or polar forms centered at . In polar coordinates , where is the angle from the positive x-axis, the boundary satisfies .[25] The interior consists of points where the distance from the center along the diagonals, with tighter angle-dependent constraints along the sides to ensure containment within the square's boundaries. This maximum distance represents half the diagonal length, providing key scale for rotated configurations. Parametric equations offer a versatile way to describe the sides and diagonals. For the axis-aligned square with vertices as above, the four sides can be parametrized piecewise over as follows: bottom side , ; right side , ; top side , ; left side , . The main diagonal is given by , for , while the other diagonal uses , . These linear parametrizations extend naturally to centered or rotated squares via translation and rotation matrices.[25]Compass and Straightedge Construction

In classical Euclidean geometry, the construction of a square using only a compass and straightedge, given a line segment as its side, is a fundamental operation that demonstrates the existence of such a figure on any finite straight line. This method, which requires erecting perpendiculars, transferring lengths, and drawing parallels, ensures the resulting quadrilateral has four equal sides and four right angles. The procedure is rigorously outlined in Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 46, where it serves as a building block for further geometric developments, such as applications in Books II, VI, and XIII.[26][27] To construct the square on a given straight line segment AB, proceed as follows:- At endpoint A, erect a perpendicular AC to AB. This is accomplished by setting the compass to a radius greater than half AB, drawing arcs centered at A and B to intersect at points equidistant from the line, and connecting those points to form the perpendicular (relying on Proposition I.11 for the right angle).[26][27]

- Along the perpendicular AC, mark point D such that AD equals AB. Transfer the length AB using the compass by placing one leg at A and adjusting the other to B, then replicating that opening from A along AC (per Proposition I.3).[26][27]

- Through D, draw line DE parallel to AB. This parallel is constructed by copying alternate angles or using corresponding segments with the compass and straightedge (as in Proposition I.31).[26][27]

- Through B, draw line BE parallel to AD, again using the parallel construction method. The intersection of BE and DE at point E completes quadrilateral ADEB as the square.[26][27]