Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Finite group

View on Wikipedia| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In abstract algebra, a finite group is a group whose underlying set is finite. Finite groups often arise when considering symmetry of mathematical or physical objects, when those objects admit just a finite number of structure-preserving transformations. Important examples of finite groups include cyclic groups and permutation groups.

The study of finite groups has been an integral part of group theory since it arose in the 19th century. One major area of study has been classification: the classification of finite simple groups (those with no nontrivial normal subgroup) was completed in 2004.

History

[edit]During the twentieth century, mathematicians investigated some aspects of the theory of finite groups in great depth, especially the local theory of finite groups and the theory of solvable and nilpotent groups.[1][2] As a consequence, the complete classification of finite simple groups was achieved, meaning that all those simple groups from which all finite groups can be built are now known.

During the second half of the twentieth century, mathematicians such as Chevalley and Steinberg also increased the understanding of finite analogs of classical groups, and other related groups. One such family of groups is the family of general linear groups over finite fields.

Finite groups often occur when considering symmetry of mathematical or physical objects, when those objects admit just a finite number of structure-preserving transformations. The theory of Lie groups, which may be viewed as dealing with "continuous symmetry", is strongly influenced by the associated Weyl groups. These are finite groups generated by reflections which act on a finite-dimensional Euclidean space. The properties of finite groups can thus play a role in subjects such as theoretical physics and chemistry.[3]

Examples

[edit]Permutation groups

[edit]

The symmetric group Sn on a finite set of n symbols is the group whose elements are all the permutations of the n symbols, and whose group operation is the composition of such permutations, which are treated as bijective functions from the set of symbols to itself.[4] Since there are n! (n factorial) possible permutations of a set of n symbols, it follows that the order (the number of elements) of the symmetric group Sn is n!.

Cyclic groups

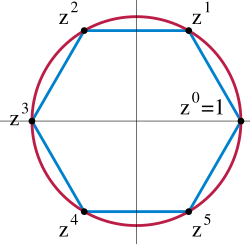

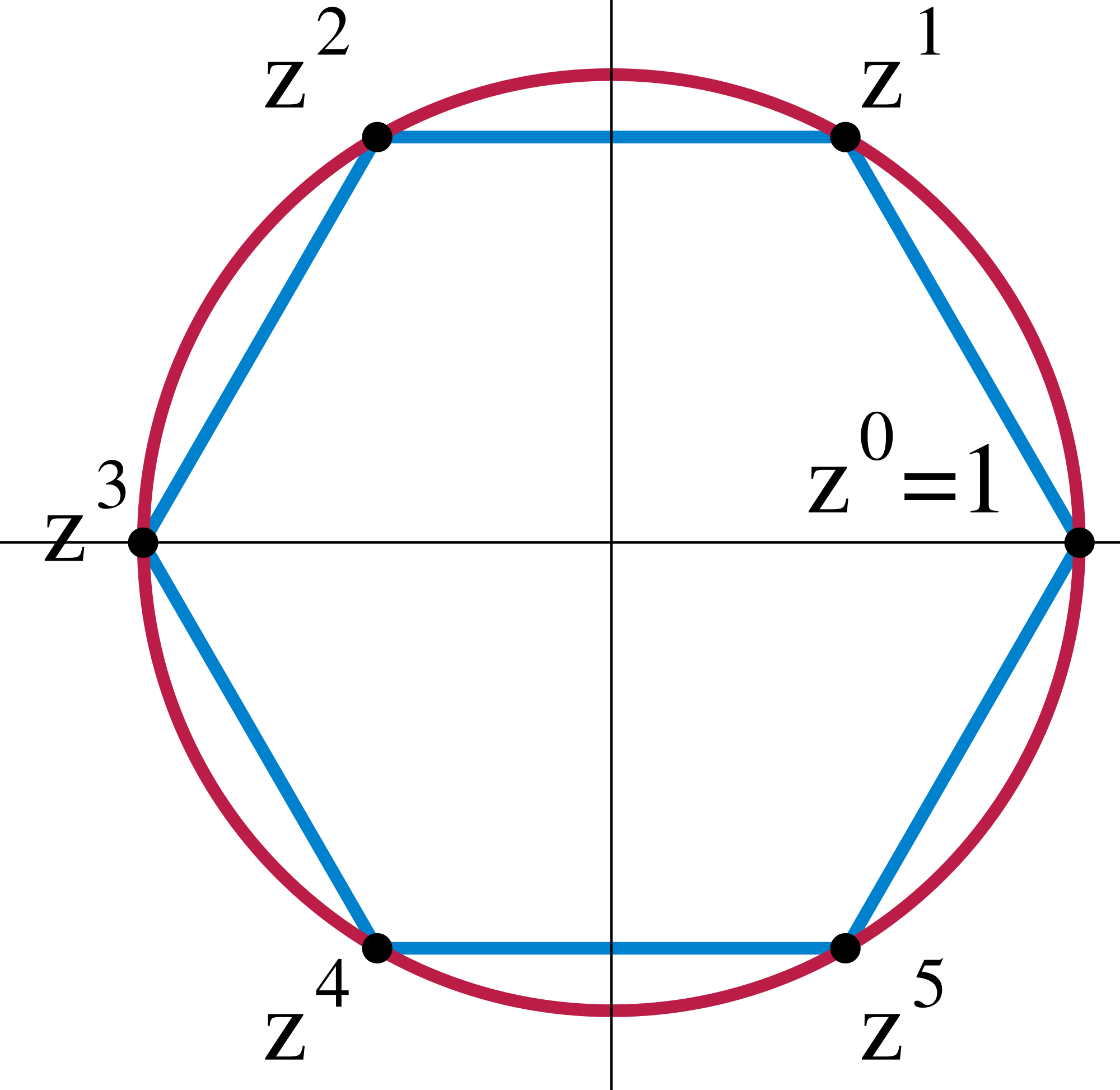

[edit]A cyclic group Zn is a group all of whose elements are powers of a particular element a where an = a0 = e, the identity. A typical realization of this group is as the complex nth roots of unity. Sending a to a primitive root of unity gives an isomorphism between the two. This can be done with any finite cyclic group.

Finite abelian groups

[edit]An abelian group, also called a commutative group, is a group in which the result of applying the group operation to two group elements does not depend on their order (the axiom of commutativity). They are named after Niels Henrik Abel.[5]

An arbitrary finite abelian group is isomorphic to a direct sum of finite cyclic groups of prime power order, and these orders are uniquely determined, forming a complete system of invariants. The automorphism group of a finite abelian group can be described directly in terms of these invariants. The theory had been first developed in the 1879 paper of Georg Frobenius and Ludwig Stickelberger and later was both simplified and generalized to finitely generated modules over a principal ideal domain, forming an important chapter of linear algebra.

Groups of Lie type

[edit]A group of Lie type is a group closely related to the group G(k) of rational points of a reductive linear algebraic group G with values in the field k. Finite groups of Lie type give the bulk of nonabelian finite simple groups. Special cases include the classical groups, the Chevalley groups, the Steinberg groups, and the Suzuki–Ree groups.

Finite groups of Lie type were among the first groups to be considered in mathematics, after cyclic, symmetric and alternating groups, with the projective special linear groups over prime finite fields, PSL(2, p) being constructed by Évariste Galois in the 1830s. The systematic exploration of finite groups of Lie type started with Camille Jordan's theorem that the projective special linear group PSL(2, q) is simple for q ≠ 2, 3. This theorem generalizes to projective groups of higher dimensions and gives an important infinite family PSL(n, q) of finite simple groups. Other classical groups were studied by Leonard Dickson in the beginning of 20th century. In the 1950s Claude Chevalley realized that after an appropriate reformulation, many theorems about semisimple Lie groups admit analogues for algebraic groups over an arbitrary field k, leading to construction of what are now called Chevalley groups. Moreover, as in the case of compact simple Lie groups, the corresponding groups turned out to be almost simple as abstract groups (Tits simplicity theorem). Although it was known since 19th century that other finite simple groups exist (for example, Mathieu groups), gradually a belief formed that nearly all finite simple groups can be accounted for by appropriate extensions of Chevalley's construction, together with cyclic and alternating groups. Moreover, the exceptions, the sporadic groups, share many properties with the finite groups of Lie type, and in particular, can be constructed and characterized based on their geometry in the sense of Tits.

The belief has now become a theorem – the classification of finite simple groups. Inspection of the list of finite simple groups shows that groups of Lie type over a finite field include all the finite simple groups other than the cyclic groups, the alternating groups, the Tits group, and the 26 sporadic simple groups.

Main theorems

[edit]Lagrange's theorem

[edit]For any finite group G, the order (number of elements) of every subgroup H of G divides the order of G. The theorem is named after Joseph-Louis Lagrange.

Sylow theorems

[edit]This provides a partial converse to Lagrange's theorem giving information about how many subgroups of a given order are contained in G.

Cayley's theorem

[edit]Cayley's theorem, named in honour of Arthur Cayley, states that every group G is isomorphic to a subgroup of the symmetric group acting on G.[6] This can be understood as an example of the group action of G on the elements of G.[7]

Burnside's theorem

[edit]Burnside's theorem in group theory states that if G is a finite group of order paqb, where p and q are prime numbers, and a and b are non-negative integers, then G is solvable. Hence each non-Abelian finite simple group has order divisible by at least three distinct primes.

Feit–Thompson theorem

[edit]The Feit–Thompson theorem, or odd order theorem, states that every finite group of odd order is solvable. It was proved by Walter Feit and John Griggs Thompson (1962, 1963)

Classification of finite simple groups

[edit]The classification of finite simple groups is a theorem stating that every finite simple group belongs to one of the following families:

- A cyclic group with prime order;

- An alternating group of degree at least 5;

- A simple group of Lie type;

- One of the 26 sporadic simple groups;

- The Tits group (sometimes considered as a 27th sporadic group).

The finite simple groups can be seen as the basic building blocks of all finite groups, in a way reminiscent of the way the prime numbers are the basic building blocks of the natural numbers. The Jordan–Hölder theorem is a more precise way of stating this fact about finite groups. However, a significant difference with respect to the case of integer factorization is that such "building blocks" do not necessarily determine uniquely a group, since there might be many non-isomorphic groups with the same composition series or, put in another way, the extension problem does not have a unique solution.

The proof of the theorem consists of tens of thousands of pages in several hundred journal articles written by about 100 authors, published mostly between 1955 and 2004. Gorenstein (d.1992), Lyons, and Solomon are gradually publishing a simplified and revised version of the proof.

Number of groups of a given order

[edit]Given a positive integer n, it is not at all a routine matter to determine how many isomorphism types of groups of order n there are. Every group of prime order is cyclic, because Lagrange's theorem implies that the cyclic subgroup generated by any of its non-identity elements is the whole group. If n is the square of a prime, then there are exactly two possible isomorphism types of group of order n, both of which are abelian. If n is a higher power of a prime, then results of Graham Higman and Charles Sims give asymptotically correct estimates for the number of isomorphism types of groups of order n, and the number grows very rapidly as the power increases.

Depending on the prime factorization of n, some restrictions may be placed on the structure of groups of order n, as a consequence, for example, of results such as the Sylow theorems. For example, every group of order pq is cyclic when q < p are primes with p − 1 not divisible by q. For a necessary and sufficient condition, see cyclic number.

If n is squarefree, then any group of order n is solvable. Burnside's theorem, proved using group characters, states that every group of order n is solvable when n is divisible by fewer than three distinct primes, i.e. if n = paqb, where p and q are prime numbers, and a and b are non-negative integers. By the Feit–Thompson theorem, which has a long and complicated proof, every group of order n is solvable when n is odd.

For every positive integer n, most groups of order n are solvable. To see this for any particular order is usually not difficult (for example, there is, up to isomorphism, one non-solvable group and 12 solvable groups of order 60) but the proof of this for all orders uses the classification of finite simple groups. For any positive integer n there are at most two simple groups of order n, and there are infinitely many positive integers n for which there are two non-isomorphic simple groups of order n.

Table of distinct groups of order n

[edit]| Order n | # Groups[8] | Abelian | Non-Abelian |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 16 | 14 | 5 | 9 |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| 21 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 23 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 24 | 15 | 3 | 12 |

| 25 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 26 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 28 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 29 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Aschbacher, Michael (2004). "The Status of the Classification of the Finite Simple Groups" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. Vol. 51, no. 7. pp. 736–740.

- ^ Daniel Gorenstein (1985), "The Enormous Theorem", Scientific American, December 1, 1985, vol. 253, no. 6, pp. 104–115.

- ^ Group Theory and its Application to Chemistry The Chemistry LibreTexts library

- ^ Jacobson 2009, p. 31

- ^ Jacobson 2009, p. 41

- ^ Jacobson 2009, p. 38

- ^ Jacobson 2009, p. 72, ex. 1

- ^ Humphreys, John F. (1996). A Course in Group Theory. Oxford University Press. pp. 238–242. ISBN 0198534590. Zbl 0843.20001.

Further reading

[edit]- Jacobson, Nathan (2009). Basic Algebra I (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-47189-1.

External links

[edit]- OEIS sequence A000001 (Number of groups of order n)

- OEIS sequence A000688 (Number of Abelian groups of order n)

- OEIS sequence A060689 (Number of non-Abelian groups of order n)

- Small groups on GroupNames

- A classifier for groups of small order

Finite group

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In abstract algebra, a group is a nonempty set equipped with a binary operation that satisfies four axioms: closure (for all , ); associativity (for all , ); identity (there exists an element such that for all , ); and invertibility (for each , there exists such that )./02%3A_Groups_I/2.02%3A_Definition_of_a_Group)[5][6] A finite group is a group whose underlying set has finite cardinality, denoted where is a positive integer called the order of the group.[7][8] Groups may use multiplicative notation (with operation and identity ) or additive notation (with operation and identity ), depending on context; for example, the set of integers modulo under addition forms a finite group of order ./02%3A_Groups_I/2.02%3A_Definition_of_a_Group)[7] The trivial group consists of a single element satisfying all group axioms, with order .[6][8] Finite groups contrast with infinite groups, where is infinite, though both share the same axiomatic structure.[7]Order of elements and groups

In a group with identity element , the order of an element , denoted or , is the smallest positive integer such that , provided such a exists; otherwise, the order is defined to be infinite.[9] In the context of finite groups, every element has finite order, as the powers of cannot cycle indefinitely within a set of bounded size.[9] Moreover, in any finite group of order , the order of every element divides , a property that highlights the structural constraints imposed by finiteness.[10] The cyclic subgroup generated by an element , denoted , consists of all integer powers of : .[9] If has finite order , then , and the order of this subgroup equals , the order of .[9] This subgroup provides insight into the local structure around , as its size directly reflects how many distinct powers produces before returning to the identity. The orders of elements thus reveal much about the overall group structure, with elements of larger orders generating larger cyclic subgroups that embed within . For example, consider the additive cyclic group of integers modulo , which has order . The order of an element (with ) is , the smallest positive integer such that .[11] Thus, generators like have order , while elements sharing factors with yield smaller orders; for instance, in , the order of 4 is 3 since . In the symmetric group of order 6, which permutes three elements, the identity has order 1, transpositions like have order 2 (as ), and 3-cycles like have order 3 (as ).[12] These orders—1, 2, and 3—all divide 6, illustrating the general relation in finite groups.Basic theorems

Lagrange's theorem

Lagrange's theorem asserts that if is a finite group and is a subgroup of , then the order of , denoted , divides the order of , denoted .[13] The proof relies on the notion of cosets. For a subgroup of , a left coset of is a set of the form where . A right coset is defined analogously as .[13] Consider the relation on given by if and only if (equivalently, ). This relation is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive, hence an equivalence relation. The equivalence classes are the distinct left cosets of , which partition into disjoint sets. Moreover, any two distinct left cosets are disjoint, and every element of belongs to exactly one left coset. Each left coset has cardinality , as there is a bijection between and given by left multiplication by .[13] Let denote the number of distinct left cosets of in , called the index of in . Then is the disjoint union of these cosets, so Since is a positive integer, it follows that divides .[13] A direct consequence is that the order of any element divides . Indeed, the cyclic subgroup generated by has order equal to the order of , and thus divides by the theorem.[13]Consequences of Lagrange's theorem

Lagrange's theorem implies that the order of every subgroup divides the order of the group, but the converse does not hold in general. For instance, the alternating group has order 12, yet it contains no subgroup of order 6.[14] A significant structural consequence arises for subgroups of small index. Specifically, any subgroup of a finite group with index is normal in . This follows because the left and right cosets of coincide, as there are only two cosets: itself and its complement .[15] Another key implication is Cauchy's theorem, which states that if is a prime dividing the order of a finite group , then contains an element of order .[16] In the context of number theory, Lagrange's theorem applies to the multiplicative group of integers modulo that are coprime to , which has order , where is Euler's totient function. For any , the order of divides , so . This is known as Euler's theorem.[17] When is prime, , yielding Fermat's little theorem: if does not divide , then . This is a special case of Euler's theorem.[18]Examples

Permutation groups

A permutation group is a subgroup of the symmetric group on a finite set, where the group operation is composition of permutations.[19] The symmetric group , or , consists of all bijections from a set of elements to itself and has order .[20] The alternating group is the subgroup of generated by even permutations, which are those expressible as a product of an even number of transpositions (2-cycles).[21] It has index 2 in , making it a normal subgroup of order .[22] For , is simple, meaning it has no nontrivial normal subgroups.[23] A transposition is a 2-cycle that swaps two elements while fixing the rest, and every permutation in can be uniquely decomposed (up to ordering) into a product of disjoint cycles, including fixed points as 1-cycles.[24] For example, the symmetric group has order 6 and is non-abelian, as compositions like and do not commute.[25] Another example is the dihedral group , which is a permutation group of order realizing the rotational and reflection symmetries of a regular -gon.[26] Permutation groups also model puzzles like the Rubik's Cube, invented in 1974, where the set of legal moves generates a subgroup of the direct product of symmetric groups on edges and corners, with order approximately .[27]Cyclic groups

A cyclic group is a group that can be generated by a single element, known as a generator. For a finite cyclic group of order , there exists an element such that , where is the identity element.) All finite cyclic groups of order are isomorphic to one another and can be represented additively as the cyclic group of integers modulo under addition. Multiplicatively, they are isomorphic to the group of th roots of unity in the complex numbers, consisting of solutions to .[28] Every subgroup of a finite cyclic group of order is itself cyclic, and for each positive divisor of , there exists exactly one subgroup of order , generated by .[29] A finite group of order is cyclic if and only if, for every divisor of , contains exactly elements of order , where denotes Euler's totient function.[29] Representative examples include the additive group , which models clock arithmetic where addition is performed modulo 12 and generated by 1. Another is the group of rotations of a regular -gon about its center, which is cyclic of order under composition.[28]Finite abelian groups

Finite abelian groups extend the structure of cyclic groups by allowing direct products of multiple cyclic components, enabling a complete classification up to isomorphism. Unlike cyclic groups, which are generated by a single element, finite abelian groups can have more complex decompositions while remaining commutative. The key result characterizing these groups is the Fundamental Theorem of Finite Abelian Groups, which states that every finite abelian group is isomorphic to a direct product of cyclic groups of prime power order:where the primes may repeat and the exponents are positive integers.[30] This theorem provides a canonical form that uniquely determines the group's isomorphism class based on its order.[30] The primary decomposition aspect of the theorem decomposes into its Sylow -subgroups for each prime dividing , yielding

where each is the -primary component, a finite abelian -group isomorphic to a direct sum of cyclic groups of orders powers of : with .[30] These components are independent, as the order of factors into distinct prime powers. The elementary divisors form refers to the collection of these prime power orders , which fully specify the group up to isomorphism when sorted appropriately.[31] In contrast, the invariant factors decomposition expresses as a direct product of cyclic groups , where divides , divides , and so on, up to , and the product of the equals .[31] This form is unique and often more compact for computation, though deriving it from the elementary divisors involves combining prime powers across different primes while preserving the divisibility condition. Both decompositions are equivalent representations of the same theorem, with transformations between them possible via prime factorization.[31] A representative example is the Klein four-group , which has order 4 and is isomorphic to . This group is non-cyclic, as no single element generates it—all non-identity elements have order 2—and its primary decomposition consists of two copies of the cyclic group of order 2. In invariant factors form, it remains , since 2 divides 2. Another illustration is the abelian group of order 8 given by , with elementary divisors 2 and 4, contrasting with the cyclic . Homomorphisms between finite abelian groups and are determined by the primary decompositions: , where each component homomorphism respects the cyclic sum structure. Endomorphisms of , i.e., , form a ring whose structure mirrors the direct sum of matrix rings over the integers modulo the relevant orders, facilitating computations of the group's module-like properties.[30]

p-groups

A finite p-group is a finite group G whose order |G| is a power of a prime p, that is, |G| = pk for some integer k ≥ 1.[32] Every nontrivial finite p-group has a nontrivial center Z(G), meaning |Z(G)| ≥ p.[33] Moreover, every maximal subgroup of a finite p-group is normal and has index p.[32] A key structural property is that every finite p-group of order pk possesses a normal subgroup of order pm for each m with 1 ≤ m ≤ k; in fact, the number of such subgroups depends on the group's structure, but their existence follows from iteratively applying the nontrivial center property to build a chain of normal subgroups.[33] Prominent examples include the quaternion group Q8 of order 8 (p=2), which is non-abelian and has presentation <a,b | a4=1, a2=b2, b-1a(b)=a-1>; its center is <a2> of order 2, and it has three subgroups of order 4, all normal and cyclic.[32] Another example is the elementary abelian p-group (Z/pZ)k, which is abelian, isomorphic to the vector space (Fp)k under addition, where every non-identity element has order p and all subgroups are normal.[32] The Frattini subgroup Φ(G) of a finite p-group G is the intersection of all its maximal subgroups, which coincides with the subgroup generated by all commutators [g,h] and all pk-th powers gpk for g ∈ G; notably, G/Φ(G) is elementary abelian of order pd, where d is the minimal number of generators of G.[32] Finite p-groups admit a chief series, a maximal normal series 1 = N0 ⊴ N1 ⊴ ⋯ ⊴ Nk = G where each factor N*i+1/Ni is a minimal normal subgroup of G/Ni and has order p, reflecting the p-group's nilpotent structure with chief factors that are elementary abelian of rank 1.[32] The Burnside basis theorem states that if G is a finite p-group, then the minimal number of generators d(G) equals the dimension of the elementary abelian group G/Φ(G) over Fp, and any generating set of G maps onto a basis of G/Φ(G) if and only if it generates G.[32]Groups of Lie type

Groups of Lie type are finite groups constructed as the fixed points under certain endomorphisms of algebraic groups defined over finite fields, serving as discrete analogues of classical Lie groups. These groups emerge from the rational points of a reductive algebraic group defined over a finite field , where is a power of a prime, typically taking the form or subgroups thereof, such as the special linear group or its projective version . The foundational construction relies on the structure of semisimple Lie algebras over the complex numbers, transported to characteristic via a Chevalley basis, which allows the generation of these finite groups uniformly across different types. The untwisted groups of Lie type, known as Chevalley groups, are classified by Dynkin diagrams corresponding to simple Lie algebras and include families such as , the projective special linear groups; , the odd-dimensional orthogonal groups over ; , the symplectic groups ; , the even-dimensional orthogonal groups; and the exceptional types , , , , and . Twisted variants, introduced to capture additional simple groups, arise by applying a Frobenius endomorphism (field automorphism combined with a graph automorphism) to the Chevalley group; prominent examples are the Suzuki groups for , the Ree groups of type for , and for . These twisted groups fill out the complete list of non-abelian finite simple groups of Lie type, excluding the alternating and sporadic families.[34] The orders of these groups follow explicit formulas derived from the Weyl group and root system structure. For instance, the order of is , where , reflecting the quotient of by its center; this yields when is odd and when is a power of 2. Similar polynomial expressions hold for higher-rank groups, scaling with raised to the dimension of the variety, modulated by factors from the Borel subgroup and Weyl group order. These formulas underscore the groups' non-abelian nature and their role as rich examples beyond cyclic or abelian structures. In the classification of finite simple groups, groups of Lie type constitute the largest infinite families, comprising 16 series (including twists) that account for the majority of all known non-abelian simple groups, with the remainder being alternating groups, cyclic groups of prime order, and 26 sporadics. This prominence stems from their systematic construction, which unifies diverse linear and orthogonal groups under algebraic geometry. The theory originated with Claude Chevalley's 1955 construction of the untwisted groups via integral forms of Lie algebras, later extended by Robert Steinberg in the late 1950s through twisting mechanisms to encompass the full spectrum of Lie-type simples.[34]Sylow theory

Sylow theorems

A Sylow -subgroup of a finite group is a maximal -subgroup of , meaning a subgroup whose order is , where is the highest power of the prime dividing .[35] Such subgroups play a central role in the structure theory of finite groups, generalizing the concept of -groups to arbitrary finite groups.[36] The first Sylow theorem guarantees the existence of such subgroups. Sylow's first theorem states that for a finite group and a prime dividing , there exists at least one Sylow -subgroup of . The proof proceeds by induction on the order of , building larger -subgroups step by step. If is a power of , then itself is the Sylow -subgroup. Otherwise, start with a nontrivial -subgroup and consider its action on the left cosets of itself by left multiplication. The fixed-point congruence implies that the normalizer properly contains , allowing construction of a larger -subgroup by induction or Cauchy's theorem.[35] Continuing this process yields a maximal -subgroup of order .[37] The second Sylow theorem addresses the conjugacy of these subgroups. Sylow's second theorem asserts that any two Sylow -subgroups of are conjugate in , and moreover, the number of distinct Sylow -subgroups satisfies and divides . The conjugacy follows from the transitivity of the conjugation action of on the set of Sylow -subgroups. For a fixed Sylow -subgroup , the stabilizer under this action is , so , which divides by Lagrange's theorem (since is divisible by ). The congruence arises from the action of on the left cosets of by left multiplication: since , this action fixes exactly one coset (the trivial one), and fixed-point theorems imply the number of cosets (i.e., ) is congruent to 1 modulo .[35][36] Finally, Sylow's third theorem provides a criterion for normality: a Sylow -subgroup of is normal in if and only if it is the unique Sylow -subgroup of . The forward direction follows immediately from the second theorem, as conjugates of a normal subgroup are itself. Conversely, if is unique, then it is fixed by all conjugations, hence normal.[37] These theorems, originally proved by Peter Ludvig Sylow in 1872, form the foundation for much of modern finite group theory.Applications of Sylow theorems

The Sylow theorems provide powerful tools for classifying finite groups of prime-power product order, particularly when the order is with distinct primes . In such a group , the number of Sylow -subgroups divides and satisfies . Since , the only possibility is , so the Sylow -subgroup is unique and hence normal in .[38] The number of Sylow -subgroups divides and satisfies , so or . The case occurs if and only if , or equivalently, divides . If , then both Sylow subgroups are normal, and is cyclic of order . If , then is a non-trivial semidirect product of its normal Sylow -subgroup by the Sylow -subgroup.[38][39] A key consequence of the Sylow theorems concerns solvability: if every Sylow subgroup of a finite group is normal, then is the direct product of its Sylow subgroups. This follows because the Sylow subgroups pairwise normalize each other, and their elements commute across distinct primes, yielding a direct decomposition into cyclic -groups for each prime dividing .[38] Such groups are necessarily solvable, as the direct product of solvable groups (here, cyclic -groups) is solvable. The Sylow theorems facilitate this by confirming the uniqueness and normality of these subgroups via for all primes .[38] The classification of groups of order 12 illustrates practical applications of Sylow counts to determine group structure. For , the possible values are or (dividing 4 and ) and or (dividing 3 and ). If , the normal Sylow 3-subgroup admits either a direct product (yielding or ) or a semidirect product by a Sylow 2-subgroup (yielding the dihedral group of order 12 or the dicyclic group of order 12). If , then or ; the case is impossible as it would imply more than 12 elements, so and , the alternating group on 4 letters. These cases exhaust the five isomorphism classes of groups of order 12.[40] The Sylow theorems also transfer to the study of composition factors by helping identify normal subgroups and quotients in a composition series. For instance, a normal Sylow -subgroup yields a quotient that is a -complement, allowing recursive decomposition; non-trivial Sylow counts can signal non-solvability or specific simple factors, as in the classification of finite simple groups where Sylow subgroups constrain possible orders.[38] Burnside's normal -complement theorem provides a criterion for the existence of a normal Hall -subgroup. Specifically, if is finite and is a Sylow -subgroup with , then has a normal -complement (a normal Hall subgroup of order ) such that . This condition leverages the Sylow theorems by ensuring the normalizer controls fusion and centralization within , often verified via and additional divisibility.[41] The theorem implies solvability in cases where such complements exist for the smallest prime dividing .[41]Group actions

Cayley's theorem

Cayley's theorem states that every finite group is isomorphic to a subgroup of the symmetric group consisting of all bijections from to itself.[42][43] This isomorphism arises from the left regular action of on itself, defined by for all .[44][43] To establish this, consider the map given by . First, is a bijection for each : it is injective because if , then left multiplication by yields ; it is surjective because for any , there exists such that .[44] Next, is a group homomorphism: , so .[44][43] Finally, is injective (hence faithful), as implies , so where is the identity.[44][43] Thus, embeds as a subgroup of , which has degree .[44] The theorem implies that every finite group can be realized concretely as a permutation group acting regularly on a set of size equal to its order, providing a bridge from abstract algebraic structures to explicit symmetries of finite sets.[45] This realization underscores the connection between group theory and the study of symmetries, as permutation groups model transformations preserving set structure.[45] For example, consider the symmetric group of order 6, generated by a 3-cycle and a transposition . The left regular action embeds into , where elements act by left multiplication on the group's own elements (listed as ). For instance, permutes these as , , , , , , corresponding to the cycle .[43] This permutation representation faithfully captures 's structure within the larger symmetric group of degree 6.[43]Burnside's lemma

In group theory, a finite group acts on a finite set if there is a map , denoted , such that the identity element fixes every point and the action is compatible with the group operation: and for all and . The orbit of an element is the set , which partitions into equivalence classes under the relation if for some . The stabilizer of is the subgroup . Burnside's lemma provides a method to count the number of orbits in such an action. For a finite group acting on a finite set , the number of orbits is given by where is the set of fixed points of .[46] This formula, originally attributed to Frobenius but popularized by Burnside, arises from averaging the number of fixed points over all group elements.[47] To sketch the proof, consider the sum , which equals by double counting the pairs with . For each orbit , the stabilizers of its elements are equal, and by the orbit-stabilizer theorem, for , so . Summing over all orbits thus yields , where is the number of orbits, proving the lemma.[48] Burnside's lemma has key applications in finite group theory, such as counting necklaces under the action of the cyclic group of rotations, where elements with cycle structures matching the necklace's symmetries contribute to fixed colorings.[49] It also enumerates conjugacy classes in by applying the lemma to the conjugation action on itself, yielding the number of classes as , where is the centralizer of .[48] Additionally, it counts conjugacy classes of subgroups, providing the number of subgroups up to isomorphism under conjugation. A representative example is counting the number of distinct colorings of an -element set with colors up to permutation by the symmetric group . The set consists of all functions from to , with acting by . A permutation fixes a coloring if is constant on the cycles of , so where is the number of cycles in . The number of orbits is thus .[48]Structure theorems

Direct and semidirect products

The direct product of two finite groups and , denoted , consists of ordered pairs with and , equipped with the componentwise operation .[50] This construction yields a group of order , and the projections onto each factor are surjective homomorphisms with kernels isomorphic to the other factor.[51] If both and are abelian, then is abelian, since for any , the commutator .[52] An internal direct product characterizes when a finite group decomposes as such a product of its subgroups: if and only if and are normal subgroups of , , and .[50] In this case, every element of uniquely writes as with and , and the multiplication follows the direct product rule.[51] A representative example is the Klein four-group, which is the direct product , consisting of elements of order dividing 2 under componentwise addition modulo 2.[53] The semidirect product provides a more general construction for building finite groups, incorporating a nontrivial action. Given finite groups and and a homomorphism , the external semidirect product has underlying set with operation .[54] This forms a group where (identified with ) is normal and (identified with ) is a subgroup, with and .[55] Internally, if is normal in , is a subgroup, , and , with conjugation in inducing the action .[54] A classic example is the symmetric group , which is the semidirect product , where acts on by inversion (the nontrivial automorphism sending ).[54] Here, the order-3 rotation subgroup is normal, and the order-2 reflection complements it. The direct product arises as a special case of the semidirect product when is the trivial homomorphism, yielding no twisting by automorphisms.[55]Solvable and nilpotent groups

A solvable group is a finite group that possesses a subnormal series such that each factor group is abelian.[56] Equivalently, the derived series of , defined by and (the commutator subgroup), terminates at the trivial subgroup after finitely many steps, i.e., for some .[56] This property captures groups that can be "built up" from abelian groups through extensions, reflecting a hierarchical structure amenable to inductive analysis.[57] All abelian groups are solvable, as their derived subgroup is trivial.[56] For instance, the symmetric group of order 6 is solvable, with derived series , where is cyclic of order 3.[58] In contrast, the alternating group of order 60 is not solvable, as its derived subgroup equals itself, preventing the series from reaching the trivial group.[56] A finite group is nilpotent if its lower central series, defined by and , terminates at the trivial subgroup, i.e., for some .[59] For finite groups, this is equivalent to the group being the direct product of its Sylow subgroups, each of which is normal.[59] Nilpotent groups form a subclass of solvable groups, as the lower central series refines to a subnormal series with abelian factors.[59] Every finite -group is nilpotent (and hence solvable), since the center of a nontrivial finite -group is nontrivial, allowing the upper central series to ascend to the whole group in finitely many steps.[59] Abelian groups are nilpotent of class 1, with trivial lower central series beyond the first term.[59] The group is solvable but not nilpotent, as its lower central series stabilizes at .[58] Burnside's normal -complement theorem provides a criterion for solvability: if is a Sylow -subgroup of a finite group such that lies in the center of its normalizer , then has a normal -complement (a normal Hall subgroup whose order is coprime to and intersects trivially).[60] Iteratively applying this theorem to the factors can establish solvability, as the existence of such complements reduces the problem to smaller solvable pieces.[60]Composition series and Jordan–Hölder theorem

A composition series of a finite group is a finite chain of subgroups such that each quotient is a simple group for ; these quotients are called the composition factors of the series.[61] Every finite group possesses at least one composition series, which can be constructed by iteratively selecting maximal normal subgroups until reaching the trivial subgroup.[62] The Jordan–Hölder theorem asserts that any two composition series of a finite group have the same length and the same composition factors up to isomorphism and permutation.[61] This uniqueness implies that the multiset of composition factors is an invariant of the group, providing a canonical decomposition into simple building blocks. The proof relies on the Schreier refinement theorem, which states that any two subnormal series of a group admit refinements that are equivalent, meaning their factor groups are isomorphic up to permutation and repetition.[63] To apply this to composition series, one refines both series using the Zassenhaus lemma to ensure maximal subnormal steps with simple factors, then removes isomorphic repetitions to match the factors pairwise; the process uses induction on the group order to handle the base case of simple groups.[63] A related concept is the chief series, a maximal chain of normal subgroups where each is a minimal normal subgroup of , known as chief factors; unlike composition factors, chief factors need not be simple but are characteristically simple, often direct products of isomorphic simple groups.[64] The Jordan–Hölder theorem extends analogously to chief series, ensuring their factors are unique up to isomorphism and permutation.[64] For example, the symmetric group has chief series , where is the Klein four-group, with chief factors , , and .[65] A corresponding composition series refines the nonsimple chief factor: , yielding simple factors , , , .[65] In solvable groups, all composition factors are abelian, specifically cyclic of prime order.[61]Simple groups

Definition and basic properties

In group theory, a finite simple group is defined as a nontrivial finite group that possesses no normal subgroups other than the trivial subgroup and the group itself.[66] This definition, originally proposed by Évariste Galois, captures groups that cannot be decomposed nontrivially via normal subgroups, making them the "atoms" of finite group structure.[66] For abelian groups, simplicity implies that the group is cyclic of prime order. Specifically, if is an abelian simple group, then for some prime , and .[67] This follows from the fact that any proper nontrivial subgroup of an abelian group is normal, so simplicity requires no such subgroups, which occurs precisely when the order is prime.[67] Non-abelian simple groups, by contrast, are infinite in number and include examples like the alternating group for , which is simple because any normal subgroup must contain 3-cycles and thus generate the entire group.[23] A key property of simple groups is their role in composition series: every finite group has a composition series where the successive quotients (composition factors) are simple groups, and by the Jordan–Hölder theorem, these factors are unique up to isomorphism and ordering.[68] For a simple group , the only maximal normal subgroup is the trivial subgroup (since itself is normal in ), emphasizing its indecomposability.[69] Although all known non-abelian finite simple groups have even order—with (order 60) as the smallest example—early conjectures sometimes questioned this, but counterexamples like confirm their existence.[66] Regarding automorphisms, the outer automorphism group measures symmetries beyond inner ones induced by conjugation; for most finite simple groups, is small, often of order 1 or 2.[70] The Schur multiplier of a finite simple group is the kernel of the universal central extension and is typically small or trivial for non-abelian cases; for instance, it is trivial for alternating groups () and cyclic groups .[71] This multiplier encodes stem extensions and has been computed for all known finite simple groups, aiding their classification.[71]Feit–Thompson theorem

The Feit–Thompson theorem states that every finite group of odd order is solvable. This result, also known as the odd order theorem, was established by Walter Feit and John G. Thompson in their seminal 1963 paper "Solvability of groups of odd order," published in the Pacific Journal of Mathematics. The proof spans 255 pages and represents one of the most intricate arguments in finite group theory at the time. The proof strategy is divided into local and global components, relying heavily on advanced techniques from representation theory. The local analysis employs character theory of finite groups, particularly the use of transfers—maps that relate characters of a group to those of its subgroups—to investigate the structure of Sylow subgroups and detect nilpotency in certain formations. Formation theory, a framework for constructing groups via subnormal series with specified factor groups, is then applied in the global phase to show that a minimal counterexample must possess a normal solvable subgroup, leading to a contradiction. Subsequent simplifications, such as those by Bender in the 1970s, have reduced the length while preserving the core ideas of character-theoretic transfers and formations. A key corollary of the theorem is that all non-abelian simple finite groups have even order, since a non-abelian simple group of odd order would contradict solvability while violating simplicity. This implication was pivotal in the classification of finite simple groups, as it eliminated the need to consider odd-order candidates beyond cyclic groups of prime order, thereby focusing efforts on even-order cases and serving as the foundational step in the decades-long project completed in the 1980s and 2000s.Classification of finite simple groups

The Classification of Finite Simple Groups (CFSG) is one of the most significant achievements in modern mathematics, providing a complete enumeration of all finite simple groups up to isomorphism. This theorem asserts that every finite simple group falls into one of four categories: cyclic groups of prime order, alternating groups for , groups of Lie type defined over finite fields, or one of 26 exceptional sporadic groups. The classification encompasses 18 infinite families in total (including the cyclic and alternating ones within the broader count) and these 26 sporadics, with no others existing.[72] The abelian simple groups are exactly the cyclic groups where is prime. The non-abelian infinite families consist of the alternating groups (), which are the even permutations on letters, and the 16 families of groups of Lie type. These Lie-type groups arise as finite analogues of Lie groups and include Chevalley groups such as the projective special linear groups , symplectic groups , and exceptional types like , all defined over the finite field where is a prime power; twisted variants, such as the unitary groups , Suzuki groups for , and Ree groups or .[68][72] The 26 sporadic simple groups are finite exceptions that do not belong to any infinite family and were discovered individually through various constructions. Notable examples include the Mathieu groups , , , , and , which are highly symmetric permutation groups related to Steiner systems; the Janko groups , , , and ; the Conway groups , , and , linked to Leech lattice symmetries; and the Monster group , the largest sporadic with order . Twenty of these sporadics are subquotients of the Monster (the "Happy Family"), while the remaining six are "pariahs" with no such connections.[73] The proof of the CFSG involved over 100 mathematicians and spanned more than 50 years, culminating in over 10,000 pages across hundreds of papers; it was initially announced as complete in 1983 by Daniel Gorenstein but required revisions, with the final gaps closed in 2004 by Michael Aschbacher and Stephen D. Smith. Ongoing projects, including a second-generation proof by Gorenstein, Lyons, and Solomon, aim to streamline and verify the result further. A key implication is that, by the Jordan–Hölder theorem, every finite group admits a composition series whose factors are these simple groups, allowing all finite groups to be understood as "built" from them via group extensions, direct products, and semidirect products.[72]Enumeration

Number of groups of order n

The number of groups of order up to isomorphism, also denoted in some literature, counts the distinct isomorphism classes of finite groups with exactly elements. This function is multiplicative in a certain sense but highly irregular, with for all (the trivial group for , and the cyclic groups and for ), and it grows rapidly thereafter, particularly when is highly composite, reflecting the increasing complexity of group structures as more prime factors are introduced. For instance, the proliferation arises from combinations of Sylow subgroups and extensions, leading to an explosion in possibilities for orders with many small prime factors. For specific cases, explicit formulas exist. When is a prime power, the enumeration of -groups of order is a central problem, with the asymptotic growth given by Higman's formula: . This reflects the polynomial-in- nature of the count in the exponent of , driven by the variety of nilpotent structures and relations in -groups. For the subclass of abelian groups of order , the fundamental theorem of finite abelian groups provides a complete classification up to isomorphism via invariant factors or elementary divisors, yielding , where the product is over primes dividing , is the -adic valuation, and denotes the partition function counting integer partitions of . In general, no closed-form formula for exists, but computational methods enable determination for moderate . Systems like the GAP (Groups, Algorithms, Programming) computer algebra package include the SmallGroups library, which catalogs all isomorphism classes of groups up to order 2000 (excluding orders 1024 and 1536 due to computational intensity), facilitating enumeration, identification, and structural analysis via algorithms for Sylow subgroups and presentations. Online databases built on such libraries, including those integrated with GAP, provide accessible lookups and verify isomorphisms for research. Asymptotically, bounds on capture the explosive growth without exact formulas. Pyber established an upper bound , where is the largest exponent in the prime factorization of , implying . These polynomial-exponential bounds highlight that is subexponential in , with the dominant contribution often from -groups for small primes like , aligning with lower bounds from the Higman-Sims asymptotic that suggest grows on the order of for prime-power .Groups of small order

The only group of order 1 is the trivial group. For a prime number , there is exactly one group of order up to isomorphism: the cyclic group . Groups of order , where is prime, are all abelian; there are exactly two up to isomorphism: the cyclic group and the elementary abelian group . For order with distinct primes , the classification depends on the divisibility condition . If does not divide , the only group is the cyclic . If divides , there are exactly two groups: the cyclic and a non-abelian semidirect product . This uses Sylow theorems to show the Sylow -subgroup is normal and the action of on it is determined by homomorphisms to . For example, for order 6 = 2 × 3 (where 2 divides 3-1), there are two groups: and . Although order 12 = 2^2 × 3 is not of the form , there are five groups up to isomorphism: the abelian ones and ; and the non-abelian ones , the dihedral group of order 12 (symmetries of regular hexagon), and the dicyclic group (also known as the binary dihedral group of order 12). These are classified using Sylow subgroups and semidirect products, with the non-abelian examples arising from actions of Sylow 3-subgroups on Sylow 2-subgroups or vice versa. The numbers of groups of small order are tabulated below for , including the count of non-abelian groups. These enumerations stem from systematic computational constructions verifying all possibilities up to isomorphism.| Order | Total groups | Non-abelian groups |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 5 | 2 |

| 9 | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | 5 | 3 |

| 13 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | 2 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | 0 |

| 16 | 14 | 9 |

| 17 | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | 5 | 3 |

| 19 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | 5 | 3 |

| 21 | 2 | 1 |

| 22 | 2 | 1 |

| 23 | 1 | 0 |

| 24 | 15 | 12 |

| 25 | 2 | 0 |

| 26 | 2 | 1 |

| 27 | 5 | 2 |

| 28 | 4 | 2 |

| 29 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | 4 | 3 |

| 31 | 1 | 0 |

| 32 | 51 | 44 |

| 33 | 1 | 0 |

| 34 | 2 | 1 |

| 35 | 1 | 0 |

| 36 | 14 | 10 |

| 37 | 1 | 0 |

| 38 | 2 | 1 |

| 39 | 2 | 1 |

| 40 | 14 | 11 |

| 41 | 1 | 0 |

| 42 | 6 | 5 |

| 43 | 1 | 0 |

| 44 | 4 | 2 |

| 45 | 2 | 0 |

| 46 | 2 | 1 |

| 47 | 1 | 0 |

| 48 | 52 | 47 |

| 49 | 2 | 0 |

| 50 | 5 | 3 |

| 51 | 1 | 0 |

| 52 | 9 | 6 |

| 53 | 1 | 0 |

| 54 | 15 | 12 |

| 55 | 2 | 1 |

| 56 | 13 | 10 |

| 57 | 2 | 1 |

| 58 | 2 | 1 |

| 59 | 1 | 0 |

| 60 | 13 | 11 |

History

Early developments

The study of finite groups originated in the 18th century through investigations into the symmetries of geometric objects and the structure of polynomial equations. Leonhard Euler, in his work on polyhedra during the 1750s and 1760s, examined the rotational symmetries of regular polyhedra such as the platonic solids, implicitly dealing with finite sets of transformations that preserved their forms; these provided early concrete examples of what would later be recognized as finite symmetry groups. In the 1770s, Joseph-Louis Lagrange advanced this area by analyzing permutations of the roots of polynomial equations in his memoir Réflexions sur la résolution algébrique des équations (1770–1771), where he explored how rearrangements of roots relate to solving equations by radicals, effectively studying the action of the symmetric group on the roots without explicitly defining the group structure.[74] This approach highlighted the finite nature of permutation sets and their role in algebraic solvability. Paolo Ruffini built on these ideas in 1799 with his Teoria generale delle equazioni, in which he proved that general polynomial equations of degree five or higher cannot be solved by radicals, using arguments involving the order and properties of permutations of roots; this result, known as Ruffini's theorem, was the first major demonstration of the limitations of radical solutions and anticipated key aspects of group-theoretic solvability.[75] Augustin-Louis Cauchy formalized early group concepts in 1812 through his memoir on symmetric functions and permutations, submitted to the French Academy and published in 1815, where he introduced the idea of a "group of substitutions" as a closed set of permutations, along with results on their orders and cycles that prefigured abstract group theory.[76] Évariste Galois, in the early 1830s, revolutionized the field by associating to each polynomial its Galois group—a finite group of permutations of the roots that encodes the symmetries of the equation's splitting field—showing in memoirs submitted to the Academy in 1830 and 1831 that solvability by radicals corresponds precisely to the group being solvable.[77] Galois's insights, though not fully appreciated until their posthumous publication in 1846, provided the abstract framework linking finite groups to the resolvability of equations.19th-century advances

The full development of Galois theory, which laid foundational insights into the structure of finite permutation groups and their relation to solvability of polynomial equations, occurred posthumously through the publication of Évariste Galois's manuscripts in 1846 by Joseph Liouville in the Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées.[78] This edition compiled Galois's earlier unpublished works, including analyses of group actions on roots, establishing key correspondences between subgroups and field extensions that influenced subsequent finite group studies.[78] In 1854, Arthur Cayley introduced the first abstract definition of a group, conceptualizing it as a set of symbols satisfying certain associative laws under a binary operation, independent of specific realizations like permutations or matrices.[79] This shift from concrete representations to abstract structures enabled broader applications in finite group theory. Cayley also proved that every finite group is isomorphic to a subgroup of the symmetric group on its elements, a result now known as Cayley's theorem.[80] Camille Jordan advanced the understanding of finite group decompositions in his 1870 treatise Traité des substitutions et des équations algébriques, where he introduced the concept of composition series as a chain of normal subgroups with simple factor groups.[81] Jordan's work demonstrated that such series provide invariant structural information about solvable groups, building on Galois's ideas to analyze permutation groups systematically.[81] In 1884, Felix Klein integrated finite groups into geometric contexts, notably applying the icosahedral rotation group to resolve the general quintic equation via modular functions and symmetries of the icosahedron.[82] Klein's approach highlighted how finite groups govern transformations in non-Euclidean geometries, as explored in his Erlangen Program of 1872, which classified geometries by their underlying symmetry groups.[83] Peter Ludvig Sylow's 1872 theorems provided crucial tools for dissecting finite groups by prime powers, stating that for a prime p dividing the group order, Sylow p-subgroups exist, are conjugate, and their number satisfies specific congruence conditions.[84] These results facilitated the study of p-group structures and influenced early classification attempts for groups of small orders.[84] Nineteenth-century efforts also included initial classifications of dyadic groups—finite 2-groups—and broader enumerations of groups up to certain orders, often leveraging Sylow theorems to identify isomorphism classes, as seen in works by mathematicians like Jordan and later compilers of tables for orders through 100.[85] These endeavors marked the transition toward systematic catalogs, though complete listings remained elusive until later refinements.[81]20th-century milestones

In the early 1900s, William Burnside made significant advances in the study of finite groups, notably posing the Burnside problem in 1902, which questions whether a finitely generated group in which every element has bounded finite order must itself be finite.[86] This problem, arising from observations on periodic groups, spurred extensive research into torsion groups and their finiteness properties, influencing later work on solvable groups.[87] Burnside also proved in 1904 that any finite group of order , where and are distinct primes and are non-negative integers, is solvable, a result that relies on character theory and marked a key step toward understanding solvability for groups with few prime factors.[88] This theorem provided early evidence that non-solvable finite groups require more complex prime power structures in their orders.[89] Around the same period, Issai Schur advanced the representation theory of finite groups, developing foundational tools in the early 1900s that linked group structure to linear algebra over the complex numbers.[90] His work, including the introduction of Schur's lemma in 1901, established that endomorphisms of irreducible representations are scalars, enabling the decomposition of representations into irreducibles and facilitating applications to group characters and solvability criteria.[91] Schur's contributions, such as proofs of the integrality of characters and orthogonality relations, became essential for analyzing finite group symmetries and were instrumental in later classification efforts. In the 1950s, Claude Chevalley introduced the Chevalley groups, providing a uniform construction of finite simple groups of Lie type over finite fields, which form one of the infinite families in the classification of finite simple groups.[92] These groups, defined via root systems and Chevalley bases for semisimple Lie algebras, include analogues of classical groups like PSL(n,q) and exceptional types, and their development in works such as Chevalley's 1955 seminar notes marked a shift toward algebraic geometry in finite group theory. This framework clarified the structure of Lie-type groups and supported ongoing classification initiatives by identifying vast classes of simple groups.[93] A landmark result came in 1963 with the Feit-Thompson theorem, which proves that every finite group of odd order is solvable, resolving a long-standing conjecture and eliminating odd-order nonsimple groups from consideration in classifications.[94] The proof, spanning over 250 pages and employing intricate character theory and formation theory, showed that no nonabelian simple group of odd order exists, thereby restricting potential simple groups to even order.[95] This theorem served as a cornerstone for the classification of finite simple groups (CFSG), narrowing the scope of the project initiated in the 1950s.[96] The CFSG, a monumental collaborative effort spanning the 1960s to 2004, culminated in the theorem that every finite simple group is either cyclic of prime order, an alternating group, a group of Lie type, or one of 26 sporadic groups.[97] Key contributions included Michael Aschbacher's 1980s program on subsystems and signalizer functors, which streamlined proofs for groups with BN-pair structures, and revisions by Robert Guralnick addressing gaps in character-theoretic arguments.[98] Richard Lyons and Ronald Solomon, building on Daniel Gorenstein's foundational work, produced a second-generation proof in the 1990s-2000s, reorganizing the classification into manageable cases and verifying completeness by 2004. This classification not only enumerated all simple building blocks of finite groups but also enabled applications in number theory and geometry.[72] Computer-assisted methods gained prominence with the 1985 publication of the ATLAS of Finite Groups, which compiled detailed tables of maximal subgroups, character tables, and constructions for all sporadic simple groups and many Lie-type groups up to certain ranks.[99] Authored by John H. Conway and collaborators, the ATLAS facilitated verification of CFSG components through computational checks on representations and fusion systems, bridging theoretical proofs with explicit data.[100] Its resources proved invaluable for identifying outer automorphisms and resolving ambiguities in the classification.[101]References

- https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Order_of_element_divides_order_of_group

- https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Burnside%27s_normal_p-complement_theorem