Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear power in space

View on Wikipedia

Nuclear power in space is the use of nuclear power in outer space, typically either small fission systems or radioactive decay, for electricity or heat. Another use is for scientific observation, as in a Mössbauer spectrometer. The most common type is a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, which has been used on many space probes and on crewed lunar missions. Small fission reactors for Earth observation satellites, such as the TOPAZ nuclear reactor, have also been flown.[1] A radioisotope heater unit is powered by radioactive decay, and can keep components from becoming too cold to function -- potentially over a span of decades.[2]

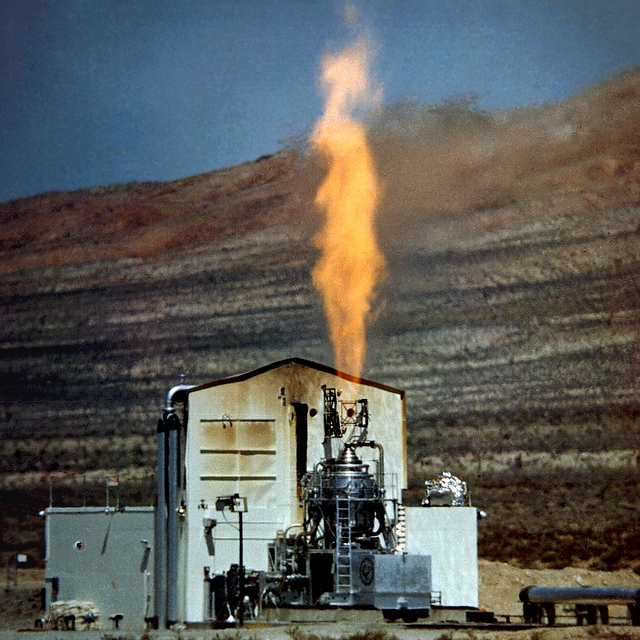

The United States tested the SNAP-10A nuclear reactor in space for 43 days in 1965,[3] with the next test of a nuclear reactor power system intended for space use occurring on 13 September 2012 with the Demonstration Using Flattop Fission (DUFF) test of the Kilopower reactor.[4]

After a ground-based test of the experimental 1965 Romashka reactor, which used uranium and direct thermoelectric conversion to electricity,[5] the USSR sent about 40 nuclear-electric satellites into space, mostly powered by the BES-5 reactor. The more powerful TOPAZ-II reactor produced 10 kilowatts of electricity.[3]

Examples of concepts that use nuclear power for space propulsion systems include the nuclear electric rocket (nuclear-powered ion thruster(s)), the radioisotope rocket, and radioisotope electric propulsion (REP).[6] One of the more explored concepts is the nuclear thermal rocket, which was ground tested in the NERVA program. Nuclear pulse propulsion was the subject of Project Orion.[7]

Hazards and regulations

[edit]

Hazards

[edit]After the ban of nuclear weapons in space by the Outer Space Treaty in 1967, nuclear power has been discussed at least since 1972 as a sensitive issue by states.[8] Space nuclear power sources may experience accidents during launch, operation, and end-of-service phases, resulting in the exposure of nuclear power sources to extreme physical conditions and the release of radioactive materials into the Earth's atmosphere and surface environment.[9] For example, all Radioisotope Power Systems (RPS) used in space missions have utilized Pu-238. Plutonium-238 is a radioactive element that emits alpha particles. Although NASA states that it exists in spacecraft in a form that is not readily absorbed and poses little to no chemical or toxicological risk upon entering the human body (e.g., in the design of American spacecraft, plutonium dioxide exists in ceramic form to prevent inhalation or ingestion by humans, and it is placed within strict safety protection systems), it cannot be denied that it may be released and dispersed into the environment, posing hazards to both the environment and human health.[10] Pu-238 primarily accumulates in the lungs, liver, and bones through inhalation of powdered form, thereby posing risks to human health.[11]

Accidents within the atmosphere

[edit]There have been several environmental accidents related to space nuclear power in history.

In 1964, a Thor-Ablestar rocket carrying the Transit 5BN-3 satellite failed to reach orbit, destroying the satellite in re-entry over the southern hemisphere. Its one kilogram of plutonium-238 fuel within the SNAP-9A Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG) was released into the stratosphere. A 1972 Department of Energy soil sample report attributed 13.4 kilocuries of Pu-238 to the accident, from the one kilogram's 17 kilocuries total. This was contrasted to the 11,600 kilocuries of strontium-90 deposited by all nuclear weapons testing.[12]

In May 1968, a Thor-Agena rocket carrying the Nimbus B satellite was destroyed by a guidance error. Its plutonium SNAP-19 RTG was recovered intact, without leakage from the Pacific sea floor, refurbished, and flown on Nimbus 3.[13]

In April 1970, the Apollo 13 lunar mission was aborted due to an oxygen tank explosion in the spacecraft's service module. Upon reentering the atmosphere, the lunar module equipped with the SNAP-27 RTG exploded and crashed into the South Pacific Ocean, with no leakage of nuclear fuel.[9] This is the only intact flown nuclear system that remains on Earth without recovery.[citation needed]

In early 1978, the Soviet spacecraft Kosmos 954, powered by a 45-kilogram highly enriched uranium reactor, went into an uncontrolled descent. Due to the unpredictable impact point, preparations were made for potential contamination of inhabited areas. This event underscored the potential danger of space objects containing radioactive materials, emphasizing the need for strict international emergency planning and information sharing in the event of space nuclear accidents. It also led to the intergovernmental formulation of emergency protocols, such as Operation Morning Light, where Canada and the United States jointly recovered 80 radioactive fragments within a 600-kilometer range in the Canadian Northwest Territories. COSMOS 954 became the first example for global emergency preparedness and response arrangements for satellites carrying nuclear power sources.[14]

NaK droplet debris

[edit]The majority of nuclear power systems launched into space remain in graveyard orbits around Earth. Between 1980 and 1989, the BES-5 and TOPAZ-I fission reactors of the Soviet RORSAT program suffered leakages of their liquid sodium–potassium alloy coolant. Each reactor lost on average 5.3 kilograms of its 13 kilogram total coolant, totaling 85 kilograms across 16 reactors. A 2017 ESA paper calculated that, while smaller droplets quickly decay, 65 kilograms of coolant still remain in centimeter-sized droplets around 800 km altitude orbits, comprising 10% of the space debris in that size range.[15]

Trapped-positron problem

[edit]

Orbital fission reactors are a source of significant interference for orbital gamma ray observatories. Unlike RTGs which largely rely on energy from alpha decay, fission reactors produce significant gamma radiation, with the uranium-235 chain releasing 6.3% of its total energy as prompt (shown below) and delayed (daughter product decay) gamma rays:[16]

Pair production occurs as these gamma rays interact with reactor or adjacent material, ejecting electrons and positrons into space:

These electrons and positrons then become trapped in the magnetosphere's flux tubes, which carry them through a range of orbital altitudes, where the positrons can annihilate with the structure of other satellites, again producing gamma rays:

These gamma rays can interfere with satellite instruments. This most notably occurred in 1987, when the TOPAZ-I nuclear reactors (6–10 kWe) aboard the twin RORSAT test vehicles Kosmos 1818 and Kosmos 1867 affected the gamma ray telescopes aboard NASA's Solar Maximum Mission and the University of Tokyo/ISAS' Ginga. TOPAZ-I remains the most powerful fission reactor operated in space, with previous Soviet missions using the BES-5 reactor (2–3 kWe) at altitudes well below gamma ray observatories.[17]

Regulations

[edit]National regulations

[edit]The presence of space nuclear sources and the potential consequences of nuclear accidents on humans and the environment cannot be ignored. Therefore, there have been strict regulations for the application of nuclear power in outer space to mitigate the risks associated with the use of space nuclear power sources among governments.[18]

For instance, in the United States, safety considerations are integrated into every stage of the design, testing, manufacturing, and operation of space nuclear systems. The NRC oversee the ownership, use, and production of nuclear materials and facilities. The Department of Energy is bound by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to consider the environmental impact of nuclear material handling, transportation, and storage.[9][19] NASA, the Department of Energy, and other federal and local authorities develop comprehensive emergency plans for each launch, including timely public communication. In the event of an accident, monitoring teams equipped with highly specialized support equipment and automated stations are deployed around the launch site to identify potential radioactive material releases, quantify and describe the release scope, predict the quantity and distribution of dispersed material, and develop and recommend protective actions.[20]

International regulations

[edit]At the global level, following the 1978 COSMOS 954 incident, the international community recognized the need to establish a set of principles and guidelines to ensure the safe use of nuclear power sources in outer space. Consequently, in 1992, the General Assembly adopted resolution 47/68, titled "Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space."[21] These principles primarily address safety assessment, international information exchange and dialogue, responsibility, and compensation. It stipulates that the principles should be revisited by the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space no later than two years after adoption.[21] After years of consultation and deliberation, in 2009, the International Safety Framework for Nuclear Power Source Applications in Outer Space was adopted to enhance safety for space missions involving nuclear power sources. It offers guidance for engineers and mission designers, although its effective implementation necessitates integration into existing processes.[22][23]

The "Safety Framework" asserts that each nation bears responsibility for the safety of its space nuclear power. Governments and international organizations must justify the necessity of space nuclear power applications compared to potential alternatives and demonstrate their usage based on comprehensive safety assessments, including probabilistic risk analysis, with particular attention to the risk of public exposure to harmful radiation or radioactive materials. Nations also need to establish and maintain robust safety oversight bodies, systems, and emergency preparedness to minimize the likelihood and mitigate the consequences of potential accidents.[23] Unlike the 1992 "Principles," the "Safety Framework" applies to all types of space nuclear power source development and applications, not just the technologies existing at the time.[22]

In the draft report on the implementation of the Safety Framework for Nuclear Power Source Applications in Outer Space published in 2023, the working group considers that the safety framework has been widely accepted and demonstrated to be helpful for member states in developing and/or implementing national systems and policies to ensure the safe use of nuclear power sources in outer space. Other member states and intergovernmental organizations not currently involved in the utilization of space nuclear power sources also acknowledge and accept the value of this framework, taking into account safety issues associated with such applications.[24]

Benefits

[edit]

Power and heat

[edit]Nuclear power systems function independently of sunlight, which is highly advantageous for outer Solar System exploration, i.e., Jupiter and beyond. All spacecraft leaving the Solar System, i.e., Pioneer 10 and 11, Voyager 1 and 2, and New Horizons use NASA RTGs, as did the outer planet missions of Galileo, Cassini, and Ulysses. However, in part, due to the global shortage of plutonium-238,[25][26][27][28] and advances in solar efficiency,[29] the more recent Jupiter missions of Juno, Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, and Europa Clipper, as well as the Jupiter trojan asteroid mission of Lucy, all opted for large solar arrays despite a relative 4% solar flux at Jupiter's orbit of 5.2 AU.

Solar power is much more commonly used for its low cost and efficiency, primarily in Earth and lunar orbit and for interplanetary missions within the inner Solar System, i.e., missions to Mercury, Venus, Mars and the asteroid belt. However, nuclear power has been used for some of these missions such as the Apollo program's SNAP-27 RTG for lunar surface use, and the MMRTG on the Mars Curiosity and Perseverance rovers.

Nuclear-based systems can have less mass than solar cells of equivalent power, allowing more compact spacecraft that are easier to orient and direct in space. This makes them useful for radar satellites such as the RORSAT program deployed by the Soviet Union. In the case of crewed spaceflight, nuclear power concepts that can power both life support and propulsion systems may reduce both cost and flight time.[30] Apollo 12 marked the first use of a nuclear power system on a crewed flight, carrying a SNAP-27 RTG to power the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package.[31]

Powering radar systems

[edit]As active electromagnetic detectors including radar observe a power-distance drop-off of , comparatively low Earth orbits are desirable.

The Soviet Union did not launch interplanetary missions beyond Mars, and generally developed few RTGs.[32] American RTGs in the 1970s supplied power in the 100 W range.[33] For the RORSAT military radar satellites (1967–1988), fission reactors, especially the BES-5, were developed to supply an average of 2 kW to the radar. At altitudes averaging 255.3 km, they would have rapidly decayed if they had used a large solar array instead.[17]

The later United States Lacrosse/Onyx radar satellite program, beginning launches in 1988, operated at altitudes of 420–718 km. To power radar at this range, a solar array reportedly 45 m in length was operated, speculated to supply 10–20 kW.[34]

Propulsion

[edit]The following technologies have been proposed and in some cases ground or space-tested for propulsion via nuclear energy.[35]

Types

[edit]Radioisotope systems

[edit]

For more than fifty years, radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) have been the United States' main nuclear power source in space. RTGs offer many benefits; they are relatively safe and maintenance-free, are resilient under harsh conditions, and can operate for decades. RTGs are particularly desirable for use in parts of space where solar power is not a viable power source. Dozens of RTGs have been implemented to power 25 different US spacecraft, some of which have been operating for more than 20 years. Over 40 radioisotope thermoelectric generators have been used globally (principally US and USSR) on space missions.[40]

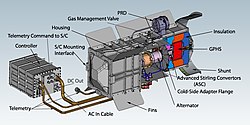

The advanced Stirling radioisotope generator (ASRG, a model of Stirling radioisotope generator (SRG)) produces roughly four times the electric power of an RTG per unit of nuclear fuel, but flight-ready units based on Stirling technology are not expected until 2028.[41] NASA plans to utilize two ASRGs to explore Titan in the distant future.[citation needed]

Radioisotope power generators include:

- SNAP-19, SNAP-27 (Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power)

- MHW-RTG

- GPHS-RTG

- MMRTG

- ASRG (Advanced Stirling radioisotope generator)

Radioisotope heater units (RHUs) are also used on spacecraft to warm scientific instruments to the proper temperature so they operate efficiently. A larger model of RHU called the General Purpose Heat Source (GPHS) is used to power RTGs and the ASRG.[citation needed]

Extremely slow-decaying radioisotopes have been proposed for use on interstellar probes with multi-decade lifetimes.[42]

As of 2011, another direction for development was an RTG assisted by subcritical nuclear reactions.[43]

Fission systems

[edit]Fission power systems may be utilized to power a spacecraft's heating or propulsion systems. In terms of heating requirements, when spacecraft require more than 100 kW for power, fission systems are much more cost effective than RTGs.[citation needed]

In 1965, the US launched a space reactor, the SNAP-10A, which had been developed by Atomics International, then a division of North American Aviation.[44]

Over the past few decades, several fission reactors have been proposed, and the Soviet Union launched 31 BES-5 low power fission reactors in their RORSAT satellites utilizing thermoelectric converters between 1967 and 1988.[citation needed]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviet Union developed TOPAZ reactors, which utilize thermionic converters instead, although the first test flight was not until 1987.[citation needed]

In 1983, NASA and other US government agencies began development of a next-generation space reactor, the SP-100, contracting with General Electric and others. In 1994, the SP-100 program was cancelled, largely for political reasons, with the idea of transitioning to the Russian TOPAZ-II reactor system. Although some TOPAZ-II prototypes were ground-tested, the system was never deployed for US space missions.[45]

In 2008, NASA announced plans to utilize a small fission power system on the surface of the Moon and Mars, and began testing "key" technologies for it to come to fruition.[46]

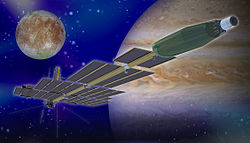

Proposed fission power system spacecraft and exploration systems have included SP-100, JIMO nuclear electric propulsion, and Fission Surface Power.[40]

A number of micro nuclear reactor types have been developed or are in development for space applications:[47]

- RAPID-L

- closed cycle magnetohydrodynamic (CCMHD) power generation system

- SP-100

- Alkali Metal Thermoelectric Converter (AMTEC)

- Kilopower

Nuclear thermal propulsion systems (NTR) are based on the heating power of a fission reactor, offering a more efficient propulsion system than one powered by chemical reactions. Current research focuses more on nuclear electric systems as the power source for providing thrust to propel spacecraft that are already in space.

Other space fission reactors for powering space vehicles include the SAFE-400 reactor and the HOMER-15. In 2020, Roscosmos (the Russian Federal Space Agency) plans to launch a spacecraft utilizing nuclear-powered propulsion systems (developed at the Keldysh Research Center), which includes a small gas-cooled fission reactor with 1 MWe.[48][49]

Project Prometheus

[edit]In 2002, NASA announced an initiative towards developing nuclear systems, which later came to be known as Project Prometheus. A major part of the Prometheus Project was to develop the Stirling Radioisotope Generator and the Multi-Mission Thermoelectric Generator, both types of RTGs. The project also aimed to produce a safe and long-lasting space fission reactor system for a spacecraft's power and propulsion, replacing the long-used RTGs. Budget constraints resulted in the effective halting of the project, but Project Prometheus has had success in testing new systems.[50] After its creation, scientists successfully tested a High Power Electric Propulsion (HiPEP) ion engine, which offered substantial advantages in fuel efficiency, thruster lifetime, and thruster efficiency over other power sources.[51]

Fission Surface Power System

[edit]In September 2020, NASA and the Department of Energy (DOE) issued a formal request for proposals for a lunar nuclear power system, otherwise known as a Fission Surface Power System (FSPS).[52] The desire for developing these systems is to assist the Artemis Project in occupying the moon and provide a reliable energy source in areas that have weeks-long lunar night cycles. Furthermore, these systems can be extended to future Mars missions, which further increase design consideration complexity due to atmospheric events, such as dust storms. NASA is collaborating with the DOE Idaho National Laboratory to progress this mission forward.

Phase 1 of the project is focused on the development of different preliminary low enriched uranium material designs to determine the feasibility of the different concepts. The system is expected to have a 40 kW (54 hp) output at 120 Vdc lasting 10 years, weigh less than 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) while fitting on a lander module, and produce less than 5 rem per year at a minimum distance of 1 km (0.62 mi).[53] Three $5 million dollar contracts were awarded in 2022 to Lockheed Martin, Westinghouse Electric Corporation, and IX (joint venture of Intuitive Machines and X-energy) to engage in industry developed reactor designs for power conversion, heat rejection, power management, and distribution systems.[54]

As it currently stands, the initial base location will be located on the southern pole of the moon so there is an almost constant stream of sun light for solar cells to power habitation modules, estimating power limits to be reached at 20 kW (27 hp). The Fission Surface Power System will be at the core of the power flow system and provide the only stable method for power generation without environmental factors. The demo reactor is expected to supply 10 kW to the grid, while the full system will provide 40 kW. This will enable the use of In situ resource utilization (ISRU).[55]

Visuals

[edit]A gallery of images of space nuclear power systems.

-

Red-hot shell containing plutonium undergoing nuclear decay, inside the Mars Science Laboratory MMRTG.[56] MSL was launched in 2011 and landed on Mars in August 2012.

-

The MSL MMRTG exterior. The white Aptek 2711 coating reflects sunlight while still transmitting heat to the Martian atmosphere

-

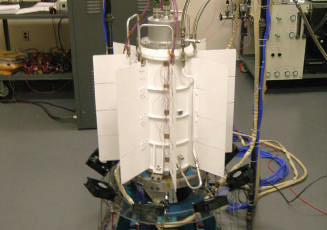

SNAP-10A Space Nuclear Power Plant, shown here in tests on the Earth, launched into orbit in the 1960s.

-

Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter. A long boom holds the reactor at a distance, while a radiation shadow shield protects the radiator fins

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Open cycles allow the nuclear fuel into the exhaust, closed cycles do not.

References

[edit]- ^ Hyder, Anthony K.; R. L. Wiley; G. Halpert; S. Sabripour; D. J. Flood (2000). Spacecraft Power Technologies. Imperial College Press. p. 256. ISBN 1-86094-117-6.

- ^ "Department of Energy Facts: Radioisotope Heater Units" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Space and Defense Power Systems. December 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Nuclear Power In Space". Spacedaily.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ "NASA - Researchers Test Novel Power System for Space Travel - Joint NASA and DOE team demonstrates simple, robust fission reactor prototype". Nasa.gov. 2012-11-26. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Ponomarev-Stepnoi, N. N.; Kukharkin, N. E.; Usov, V. A. (March 2000). ""Romashka" reactor-converter". Atomic Energy. 88 (3). New York: Springer: 178–183. doi:10.1007/BF02673156. ISSN 1063-4258. S2CID 94174828.

- ^ "Radioisotope Electric Propulsion: Enabling the Decadal Survey Science Goals for Primitive Bodies" (PDF). Lpi.usra.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Everett, C.J.; Ulam S.M. (August 1955). "On a Method of Propulsion of Projectiles by Means of External Nuclear Explosions. Part I" (PDF). Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 25, 2012.

- ^ "Nuclear Power Sources in Space". Space Legal Issues. 2019-07-24. Archived from the original on 2021-06-22. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ a b c Tchouaso, Modeste Tchakoua; Alam, Tariq Rizvi; Prelas, Mark Antonio (2023), "Space nuclear power", Photovoltaics for Space, Elsevier, pp. 443–488, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-823300-9.00014-5, ISBN 978-0-12-823300-9

- ^ "About Plutonium-238 | About RPS". NASA RPS: Radioisotope Power Systems. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Agency for Toxic Substances and Diseases Registry. "Plutonium | Public Health Statement | ATSDR". wwwn.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Hardy, Jr., E. P.; Krey, P. W.; Volchok, H. L. (1972-01-01). "Global Inventory and Distribution of 238-Pu from SNAP-9A". U.S. Department of Energy – Office of Scientific and Technical Information. doi:10.2172/4689831. OSTI 4689831.

- ^ "Nimbus B". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ International Atomic Energy Agency (2020-10-28). "Ensuring Safety on Earth from Nuclear Sources in Space". www.iaea.org. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Wiedemann, Carsten; Gamper, Eduard; Horstmann, Andre; Braun, Vitali; Stoll, Enrico (2017). "The contribution of NaK droplets to the space debris environment". ESA Proceedings Database (in German). Retrieved 2024-08-03.

- ^ Nuclear fission and fusion, and neutron interactions, National Physical Laboratory Archive.

- ^ a b Grahn, Sven. "The US-A program (Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satelites)". Sven's Space Place. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ Hussein, Esam M.A. (December 2020). "Emerging small modular nuclear power reactors: A critical review". Physics Open. 5 100038. doi:10.1016/j.physo.2020.100038. ISSN 2666-0326.

- ^ El-Genk, Mohamed (2010), "Safety guidelines for space nuclear reactor power and propulsion systems", Space Safety Regulations and Standards, Elsevier, pp. 319–370, doi:10.1016/b978-1-85617-752-8.10026-1, ISBN 978-1-85617-752-8

- ^ Barco, Alessandra; Ambrosi, Richard M.; Williams, Hugo R.; Stephenson, Keith (June 2020). "Radioisotope power systems in space missions: Overview of the safety aspects and recommendations for the European safety case". Journal of Space Safety Engineering. 7 (2): 137–149. Bibcode:2020JSSE....7..137B. doi:10.1016/j.jsse.2020.03.001. ISSN 2468-8967.

- ^ a b "NPS Principles". www.unoosa.org. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ a b Summerer, L.; Wilcox, R.E.; Bechtel, R.; Harbison, S. (June 2015). "The International Safety Framework for nuclear power source applications in outer space—Useful and substantial guidance". Acta Astronautica. 111: 89–101. Bibcode:2015AcAau.111...89S. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2015.02.007. ISSN 0094-5765.

- ^ a b International Atomic Energy Agency (2009). Safety Framework for Nuclear Power Source Applications in Outer Space (Report). p. 1.

- ^ "A/AC.105/C.1/124 - Final report on the implementation of the Safety Framework for Nuclear Power Source Applications in Outer Space and recommendations for potential enhancements of the technical content and scope of the Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space: Prepared by the Working Group on the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space". www.unoosa.org. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ David Dickinson (March 21, 2013). "U.S. to restart plutonium production for deep space exploration". Universe Today. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell. "Plutonium Shortage Could Stall Space Exploration". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell. "The Plutonium Problem: Who Pays For Space Fuel?". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Wall, Mike (April 6, 2012). "Plutonium Production May Avert Spacecraft Fuel Shortage". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Breaks Solar Power Distance Record". NASA. January 13, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Zaitsev, Yury. "Nuclear Power In Space". Spacedaily. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Apollo 12 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. pp. 43–44. Retrieved May 7, 2025.

- ^ "Nuclear Powered Payloads". Gunter's Space Page. 2024-08-19. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ "Atomic Power in Space II: A History 2015" (PDF). inl.gov. Idaho National Laboratory. September 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Onyx 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (Lacrosse 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)". Gunter's Space Page. 2024-08-19. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ Gabrielli, Roland Antonius; Herdrich, Georg (2015). "Review of Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Systems". Progress in Aerospace Sciences. 79: 92–113. doi:10.1016/j.paerosci.2015.09.001.

- ^ Chapline, G.; Dickson, P.; Schnitzler, B. (18 September 1988). Fission fragment rockets: A potential breakthrough (PDF). International reactor physics conference. Jackson Hole, Wyoming, USA. OSTI 6868318.

- ^ Clark, R.; Sheldon, R. (10–13 July 2005). Dusty Plasma Based Fission Fragment Nuclear Reactor (PDF). 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit. Tucson, Arizona: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (published 15 April 2007). AIAA Paper 2005-4460.

- ^ Ronen, Yigal; Shwageraus, E. (2000). "Ultra-thin 241mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 455 (2): 442–451. Bibcode:2000NIMPA.455..442R. doi:10.1016/s0168-9002(00)00506-4.

- ^ Hall, Loura; Weed, Ryan (9 January 2023). "Aerogel Core Fission Fragment Rocket Engine". NASA. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ a b

Mason, Lee; Sterling Bailey; Ryan Bechtel; John Elliott; Mike Houts; Rick Kapernick; Ron Lipinski; Duncan MacPherson; Tom Moreno; Bill Nesmith; Dave Poston; Lou Qualls; Ross Radel; Abraham Weitzberg; Jim Werner; Jean-Pierre Fleurial (18 November 2010). "Small Fission Power System Feasibility Study — Final Report". NASA/DOE. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

Space Nuclear Power: Since 1961 the U.S. has flown more than 40 Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) with an essentially perfect operational record. The specifics of these RTGs and the missions they have powered have been thoroughly reviewed in the open literature. The U.S. has flown only one reactor, which is described below. The Soviet Union has flown only 2 RTGs and had shown a preference to use small fission power systems instead of RTGs. The USSR had a more aggressive space fission power program than the U.S. and flew more than 30 reactors. Although these were designed for short lifetime, the program demonstrated the successful use of common designs and technology.

- ^ "Stirling Technical Interchange Meeting" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ^ "Innovative Interstellar Probe". JHU/APL. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Arias, F. J. (2011). "Advanced Subcritical Assistance Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator: An Imperative Solution for the Future of NASA Exploration". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 64: 314–318. Bibcode:2011JBIS...64..314A.

- ^ A.A.P.-Reuter (1965-04-05). "Reactor goes into space". The Canberra Times. 39 (11, 122). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 5 April 1965. p. 1. Via National Library of Australia. Retrieved on 2017-08-12 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/131765167.

- ^ National Research Council (2006). Priorities in Space Science Enabled by Nuclear Power and Propulsion. National Academies. p. 114. ISBN 0-309-10011-9.

- ^ "A Lunar Nuclear Reactor | Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute". Sservi.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ "Nuclear Reactors for Space - World Nuclear Association". World-nuclear.org. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Page, Lewis (5 April 2011). "Russia, NASA to hold talks on nuclear-powered spacecraft Muscovites have the balls but not the money". The Register. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Breakthrough in quest for nuclear-powered spacecraft". Rossiiskaya Gazeta. October 25, 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Nuclear Reactors for Space". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "NASA Successfully Tests Ion Engine". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "NASA to seek proposals for lunar nuclear power system". Space News. 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Overview of NASA Fission Surface Power" (PDF). 2023.

- ^ "NASA Announces Artemis Concept Awards for Nuclear Power on Moon". NASA. 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Lunar Surface Power Architecture Concepts". IEEE. 2023.

- ^ "Technologies of Broad Benefit: Power". Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

External links

[edit]- KRUSTY - Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling Technology

- Small Fission Power System Feasibility Study

- Nuclear Power in Space - Office of Nuclear Energy - U.S. Department of Energy(.pdf)

- SAFE-400 paper (fission reactor)

- Design Concept for a Nuclear Reactor-Powered Mars Rover

- David Poston, "Space Nuclear Power: Fission Reactors"

- Design and Testing of Small Nuclear (.pdf file)

- Overview of NASA and nuclear power in space

- NASA Seeks Nuclear Power for Mars (December 2017)

Nuclear power in space

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early concepts and ground tests (1940s–1960s)

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and Department of Defense studies identified the potential of radioisotope decay heat for compact, long-duration power sources suitable for emerging space applications, where solar and chemical batteries proved inadequate for extended missions.[11] These concepts built on post-World War II nuclear advancements, emphasizing fission and decay products like strontium-90 and plutonium-238 to generate electricity via thermoelectric conversion, addressing the limitations of mass and reliability in vacuum environments.[12] The Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power (SNAP) program, initiated by the AEC in the late 1950s in response to Sputnik's launch, formalized these ideas through development of both radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and compact fission reactors for space.[13] The program's first critical assembly test occurred in October 1957, followed by ground testing of the SNAP Experimental Reactor to validate low-power fission designs.[14] SNAP-1, an early RTG prototype using strontium-90 fuel, underwent ground qualification tests in 1959, producing approximately 2 watts of electrical power to demonstrate thermoelectric efficiency under simulated space conditions.[15] Throughout the early 1960s, ground tests intensified at facilities like the Santa Susana Field Laboratory and Test Area North, including SNAP-2 experimental reactor operations from 1960 to 1961, which achieved criticality and sustained low-power fission for systems engineering data.[13] The SNAPTRAN series conducted destructive safety tests on reactors like SNAP-10A prototypes, simulating accident scenarios such as reentry and coolant loss to assess containment and radiological risks.[16] SNAP-8 developmental reactors were also ground-tested, targeting higher outputs up to 500 watts for potential satellite applications, though challenges with thermoelectric materials and shielding persisted.[13] Soviet efforts paralleled U.S. work, with conceptual studies in the 1950s leading to ground tests of fast-spectrum reactors for direct thermoelectric power conversion. The Romashka reactor, a 180-kilowatt thermal prototype using enriched uranium, began testing on August 14, 1964, at a Semipalatinsk facility, operating for over 5,000 hours and generating electricity for about 1,600 hours to evaluate space-relevant compactness and heat-to-electricity efficiency.[17] These tests informed subsequent designs but highlighted issues like fuel swelling under neutron flux, delaying orbital deployment.[17]Cold War operational deployments (1960s–1980s)

![SNAP-27 RTG deployed on the Moon during Apollo missions][float-right] The United States initiated operational use of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) in space with the SNAP-3 model aboard the Transit 4A navigation satellite on June 29, 1961, providing 2.7 watts of electrical power from plutonium-238 decay heat.[18] Subsequent Transit satellites employed SNAP-9A RTGs starting in 1963, enabling reliable navigation for Polaris submarines by the mid-1960s through continuous orbital operation.[19] The SNAP-19 RTG powered the Nimbus III meteorological satellite launched on April 14, 1969, marking the first use for continuous global weather monitoring with approximately 28 watts output.[3] For lunar missions, SNAP-27 RTGs, each generating about 70 watts, were deployed on the Moon's surface by Apollo 12 through 17 crews between November 1969 and December 1972 to energize the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Packages (ALSEPs), with some units operating for over eight years before intentional shutdowns.[20] Planetary probes like Pioneer 10 and 11 (launched 1972 and 1973) and Viking 1 and 2 Mars landers (1975-1976) relied on SNAP-19 variants for long-duration power, while military communications satellites LES-8 and LES-9 (1976) used Multi-Hundred Watt (MHW) RTGs producing up to 60 watts each.[21] Overall, the U.S. deployed dozens of RTGs across navigation, scientific, and military applications during this era, with no mission failures attributed to the power systems themselves, though a 1968 Nimbus B launch failure led to ocean recovery and refurbishment of its SNAP-19 RTG for later reuse.[22] In contrast, the Soviet Union emphasized compact fission reactors for high-power needs, launching the first experimental reactor satellite, Kosmos 367, in 1970, but achieving operational status with the Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite (RORSAT) program using BES-5 thermionic reactors fueled by 30-50 kg of enriched uranium-235, each delivering 3-5 kW electrical and 100 kW thermal power for ocean surveillance radars.[23] From 1970 to 1988, approximately 33 RORSATs were placed in low Earth orbit, with reactors designed for 130-140 day lifespans before boosted to disposal orbits where fuel rods were ejected into the atmosphere to minimize intact reentry risks.[24] The program detected U.S. naval assets during the Cold War, but suffered reliability issues, including the 1978 Cosmos 954 failure where a reactor core reentered over Canada, scattering 65,000 radioactive fragments across 124,000 square kilometers and prompting a joint U.S.-Canadian cleanup costing $14 million.[25] Similarly, Cosmos 1402 in 1982 malfunctioned, leading to partial reentry over the Atlantic and Indian Oceans with unretrieved fuel. Routine operations also released sodium-potassium (NaK) coolant droplets into orbit, creating long-lived debris hazards observable into the 21st century.[26] The U.S. tested a single reactor, SNAP-10A, in 1965, which generated 500 watts for 43 days before a non-nuclear component failure, reflecting a strategic preference for safer, lower-power RTGs over reactors due to reentry and proliferation concerns.[27] By the 1980s, over 30 Soviet reactors had operated in space, vastly exceeding U.S. fission deployments but at higher environmental and safety costs.[26]Post-Cold War transitions and RTG dominance (1990s–2010s)

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia terminated its operational program of space-based nuclear fission reactors, which had deployed over 30 RORSAT units through 1988, amid international concerns over reentry incidents like Cosmos 954 in 1977 and Cosmos 1402 in 1983 that dispersed radioactive material.[4] This shift aligned with strengthened UN principles on nuclear power sources in outer space, emphasizing risk mitigation and favoring non-fissile systems for post-Cold War missions.[28] The United States, having abandoned reactor development after the SNAP-10A test in 1965 due to technical failures and safety priorities, further entrenched radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) as the dominant nuclear power technology for deep-space applications, leveraging plutonium-238 decay heat for reliable, maintenance-free electricity over solar-weak environments.[29] The General Purpose Heat Source RTG (GPHS-RTG), qualified in the 1980s with improved safety features like iridium-clad fuel pellets to contain reentry dispersal, powered pivotal NASA missions starting in the 1990s.[30] Ulysses, launched October 6, 1990, employed one GPHS-RTG generating 283 watts electrical (We) initially to enable polar solar orbit studies, operating until June 2009 despite helium buildup reducing output to 189 We by mission end.[21] Cassini-Huygens, launched October 15, 1997, utilized three GPHS-RTGs providing 295.7 We total for its 20-year Saturn exploration, including Huygens probe descent to Titan in 2005, where RTG autonomy exceeded solar alternatives in the planet's faint sunlight.[31] These systems demonstrated RTG longevity, with Cassini's power declining predictably to support extended operations until deliberate atmospheric disposal in 2017.[21] Into the 2000s, RTG reliance persisted amid U.S. plutonium-238 production cessation in 1988, forcing allocation of stockpiled general-purpose heat sources (GPHS) modules—each containing 150 g of Pu-238 oxide—for high-priority missions.[30] New Horizons, launched January 19, 2006, carried one GPHS-RTG delivering 249.6 We for its Kuiper Belt trajectory, achieving Pluto flyby in 2015 and Arrokoth encounter in 2019 at distances rendering solar power infeasible.[21] RTG dominance reflected causal advantages in thermal management and power density for uncrewed probes, avoiding reactor complexities like criticality control and coolant handling that had plagued Soviet efforts.[4] The Multi-Mission RTG (MMRTG), developed from 2000s to address Mars surface needs with lower output but higher efficiency via lead-telluride thermocouples, debuted on the Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity rover), launched November 26, 2011, generating 113 We from one unit to power mobility, instruments, and survival through dust storms that crippled solar rovers like Spirit and Opportunity.[21] This transition underscored RTGs' versatility for planetary landers, sustaining Curiosity's Gale Crater investigations into the 2020s with minimal degradation.[31] Russian post-Soviet space nuclear use remained minimal, limited to legacy RTG designs for occasional remote sensing without reactor revival, ceding global leadership to U.S. systems amid economic constraints and safety moratoriums.[4]Recent resurgence and international initiatives (2020s)

In the early 2020s, NASA intensified efforts to deploy fission-based nuclear power systems for lunar and planetary surface operations, driven by the limitations of solar power in shadowed regions and the power demands of sustained human presence under the Artemis program. The agency's Fission Surface Power (FSP) initiative, building on the Kilopower prototype tested via the KRUSTY experiment in 2018, advanced designs for scalable 10-kilowatt electric reactors using uranium-235 fuel and Stirling engines for efficiency.[32] In November 2021, NASA and the Department of Energy's Idaho National Laboratory solicited industry partners to develop, fabricate, and test such a system for lunar deployment targeted by the late 2020s, emphasizing autonomous operation without atmospheric cooling.[33] A 2020 White House national strategy further prioritized uranium fuel processing for space nuclear systems by the mid-2020s, aiming to enable kilowatt-scale power for habitats and rovers.[34] Parallel U.S. initiatives explored nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) to reduce Mars transit times from months to weeks, offering specific impulses of 800-900 seconds compared to chemical rockets' 450 seconds. In January 2023, NASA partnered with DARPA on the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) program, planning an in-orbit NTP demonstration by 2027 using low-enriched uranium cores heated to over 2,500 K to expel hydrogen propellant.[35] However, DARPA canceled DRACO in July 2025, citing plummeting launch costs that diminished NTP's near-term advantages for cislunar operations and new cost-benefit analyses favoring chemical propulsion scalability.[36] Internationally, Russia and China formalized cooperation on nuclear power for their International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), announcing in 2023 plans for a lunar surface reactor by 2033-2035 to supply megawatts for electrolysis, life support, and resource extraction.[37] China detailed this in April 2025, targeting a reactor integrated with the Chang'e-8 mission's groundwork for a 2030 crewed landing, leveraging gas-cooled designs for thermal management in vacuum.[38] In response to this competition, NASA accelerated its lunar fission timeline in August 2025, expediting a 10-40 kilowatt reactor delivery by 2030 to outpace adversaries, as stated by interim administrator Sean Duffy amid geopolitical tensions over space resource claims.[39] These efforts reflect a broader revival of space nuclear technology, spurred by empirical needs for dense, reliable energy beyond solar intermittency, though challenges persist in radiation shielding, launch safety, and international treaty compliance under the Outer Space Treaty.[40]Technical Fundamentals

Radioisotope decay-based systems

Radioisotope decay-based systems in space primarily employ radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from the alpha decay of plutonium-238 (Pu-238) into electricity using the Seebeck effect across semiconductor thermocouples. Pu-238 is favored due to its 87.7-year half-life, which supports multi-decade missions, and its specific thermal power output of 0.56 watts per gram, minimizing mass while providing continuous energy without moving parts or sunlight dependence.[41][4] The heat source consists of Pu-238 dioxide pellets encapsulated in iridium-clad General Purpose Heat Source (GPHS) modules, designed to operate at hot-junction temperatures around 1000°C, with cold junctions cooled by spacecraft radiators or deep-space vacuum.[3] Thermocouples, typically pairs of p-type and n-type materials like lead telluride or silicon-germanium alloys, exploit temperature differentials to produce direct current, achieving conversion efficiencies of 5-7%.[4][42] Early designs, such as the SNAP-27 (70 We for Apollo lunar surface experiments, 1969-1972), evolved to MHW-RTGs (158 We each, three units totaling 470 We at launch for Voyager 1 and 2 in 1977), GPHS-RTGs (292 We for Cassini in 1997 and Galileo in 1989), and the Multi-Mission RTG (MMRTG, 110 We from 2000 W thermal for Curiosity in 2012).[3][43] Power degrades at ~0.8% per year due to Pu-238 decay, yet Voyager RTGs continue operating beyond 45 years, powering instruments at reduced levels around 240 We total as of 2023.[4] Safety features include multi-layered containment with graphite impact shells and aeroshell designs tested for launch failures, reentry, and surface impacts; the SNAP-27 from Apollo 13 survived ocean impact intact in 1970 with no radionuclide release.[3][44] U.S. RTGs have powered over 25 missions without causing spacecraft failures or environmental releases, contrasting with some Soviet-era ground-based RTG mismanagement unrelated to orbital operations.[8] Radioisotope heater units (RHUs), using similar Pu-238 sources (~1 W thermal each, no electricity), supplement RTGs by preventing cold-induced failures in electronics and mechanisms across missions like Cassini and New Horizons.[45]Fission reactor designs

Fission reactor designs for space applications prioritize low mass, passive safety features, and efficient thermal management in vacuum environments, often employing fast-spectrum cores with highly enriched uranium fuels to achieve criticality without bulky moderators. Liquid metal coolants like sodium-potassium (NaK) alloy enable high-temperature operation and compatibility with direct energy conversion methods such as thermionic or thermoelectric systems, minimizing moving parts for reliability over years-long missions.[4] The United States' SNAP-10A, launched on April 3, 1965, represented the first operational space fission reactor, featuring a zirconium hydride (ZrH)-moderated core with enriched uranium-235 fuel elements, NaK coolant, and thermoelectric conversion via silicon-germanium junctions, yielding approximately 500 watts electrical from 30-45 kilowatts thermal at a system mass of 435 kg.[4][46] Intended for one-year operation, it generated power for 43 days before a non-nuclear voltage regulator failure halted output, with the reactor core remaining intact in low Earth orbit.[4] Soviet designs emphasized unmoderated fast reactors for compactness, as seen in the BES-5 (Buk) reactors deployed in the RORSAT ocean surveillance program from 1967 to 1988, where 31 units used uranium-molybdenum (U-Mo) or uranium carbide (UC₂) fuel in disc or rod configurations, NaK coolant, and thermoelectric or early thermionic converters to produce under 5 kWe from less than 100 kWt thermal per reactor, with individual systems weighing around 385 kg including lithium hydride shielding.[4][47] Earlier prototypes like Romashka, tested in 1969, omitted coolant for direct thermoelectric contact on UC₂ fuel discs, delivering 0.8 kWe from 40 kWt in a 40 kg core.[4] Advanced iterations culminated in TOPAZ-I reactors on Kosmos 1818 and 1867 satellites in 1987, incorporating uranium dioxide (UO₂) fuel in thermionic fuel elements (TFEs) with NaK cooling and cesium-vapor thermionic conversion for 5-10 kWe from 150 kWt, at a 320 kg mass excluding payload.[4] Contemporary designs build on these foundations with passive heat pipe transport to eliminate pumps. NASA's Kilopower, prototyped via the 2018 KRUSTY ground test, uses a cast highly enriched uranium-10% molybdenum (U-10Mo) alloy core (about 32 kg fuel with 93% ²³⁵U enrichment), beryllium oxide reflector, and sodium-filled heat pipes to passively transfer heat to Stirling engines for 1 kWe output from 4-5 kWt thermal, emphasizing subcritical launch safety, inherent shutdown via negative reactivity feedback, and scalability to 10 kWe units without active control rods.[48][49] The KRUSTY demonstration achieved full-power operation for 28 hours, validating neutronics, thermal hydraulics, and power conversion in a compact, low-mass system suitable for lunar or planetary surfaces.[48]Hybrid and advanced concepts

Bimodal nuclear reactor designs integrate fission-based thermal propulsion with electrical power generation, utilizing a single reactor core to operate in dual modes. In propulsion mode, the reactor achieves high temperatures to heat a propellant for thrust, while in power mode, it supplies lower-temperature heat for electricity production via static or dynamic converters. This approach enhances mission efficiency by reducing system mass and complexity compared to separate power and propulsion units. For instance, bimodal systems proposed for Mars missions employ cermet fuel and thermoelectric or Brayton cycle conversion to deliver both orbital transfer propulsion and onboard power, with historical concepts like the Bimodal Nuclear Thermal Rocket (BNTR) demonstrating potential weight reductions for lunar and interplanetary vehicles.[50][51] Hybrid fission-fusion reactor concepts leverage fusion neutrons to induce fission in a subcritical blanket, aiming for compact, high-efficiency power sources suitable for deep-space probes. One such design uses lattice confinement fusion within a metal lattice loaded with deuterium, triggered by X-ray beams and a neutron source to achieve fusion at near-ambient temperatures, with the resulting neutrons driving fast fission in materials like depleted uranium or thorium. This method, proposed for penetrating Europa's thick ice shell, offers advantages in size, waste reduction, and scalability for nuclear thermal or electric propulsion over conventional fission reactors, though reaction rates require further enhancement for operational power levels. Selected for NASA's NIAC Phase I in 2023, it represents an experimental approach to overcoming limitations in traditional radioisotope or pure fission systems.[52] Advanced dynamic energy conversion systems improve efficiency beyond static thermoelectric methods by employing mechanical cycles to convert nuclear heat to electricity. The JETSON system, for example, pairs a fission reactor with Stirling engines to generate 6 to 20 kWe—up to four times the output of equivalent solar arrays—while maintaining the reactor inert during launch for safety. Building on NASA's 2018 KRUSTY ground demonstration, it supports electric propulsion via Hall thrusters and is in preliminary design review as of 2023. Similarly, dynamic radioisotope power systems use plutonium-238 decay heat with Stirling or Brayton converters for higher specific power, addressing needs for shadowed or distant environments where solar power diminishes. These technologies, under NASA and DOE development since the 2010s, prioritize gas-bearing mechanisms for longevity and efficiency exceeding 20-30% in prototypes.[53][54][55] Emerging hybrid power-propulsion architectures combine micro-fission reactors with electric and chemical thrusters for versatile spacecraft operations. A U.S. Space Force-funded initiative, launched in 2024, targets ~100 kW systems using lightweight microreactors, Hall or magnetoplasmadynamic thrusters, and advanced converters like thermionic cells, integrated with chemical rockets for thrust augmentation. Led by the University of Michigan with partners including Ultra Safe Nuclear, it emphasizes dual-use fuels and waste heat management to boost maneuverability and resilience in contested orbits. Such concepts extend beyond pure power generation, enabling responsive space assets while mitigating risks through modular, activatable designs.[56][57]Applications

Onboard power and thermal management

Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) primarily supply onboard electrical power for spacecraft through the conversion of heat from the alpha decay of plutonium-238 (Pu-238) into electricity via the Seebeck effect in thermocouple arrays, typically using lead-telluride or silicon-germanium materials. Each gram of Pu-238 generates approximately 0.56 watts of thermal power, with half-life of 87.7 years enabling long-term operation; for instance, the Multi-Mission RTG (MMRTG) on NASA's Perseverance rover, deployed in 2021, delivers about 110 watts electrical from 2,000 watts thermal at beginning of mission, with conversion efficiency around 6-7%.[58][59] Excess heat, comprising over 90% of generated energy, is managed through the RTG's finned outer housing, which radiates infrared emissions to deep space via the Stefan-Boltzmann law, maintaining hot junctions at 500-1000°C and cold sides near ambient spacecraft temperatures of -100°C to 100°C depending on solar exposure.[60] This passive thermal rejection prevents overheating while the inherent heat source counters cryogenic conditions in shadowed orbits or distant heliocentric distances, as demonstrated by Voyager 2's three RTGs sustaining operations beyond 47 years since 1977 launch.[61] ![SNAP-27 RTG deployed on the lunar surface during Apollo 12 mission in 1969][float-right] Fission reactors offer higher power densities for demanding applications, generating electricity from controlled uranium-235 fission heat transferred via liquid metal coolants like sodium-potassium eutectic (NaK, typically 78% potassium by weight), which boasts high thermal conductivity (around 25 W/m·K) and operates liquid from -12°C to 785°C, facilitating efficient heat transport without high-pressure systems. The U.S. SNAP-10A reactor, orbited in 1965, produced 500 watts electrical from 30 kilowatts thermal using thermoelectric conversion, with NaK circulated by electromagnetic pumps to thermoelectric modules and rejected via deployable radiators spanning several square meters to achieve equilibrium in vacuum.[4] Soviet RORSAT reactors, operational from 1967 to 1988, employed similar NaK cooling in TOPAZ-I designs (5-10 kWe output), where heat pipes and cesium-vapor thermionic converters minimized moving parts, though NaK leaks posed re-entry risks as evidenced by Cosmos 954's 1978 dispersal of 65,000 curies.[4] Thermal management relies on multi-layer insulation, variable-geometry radiators, and startup sequences delaying criticality until orbit to avoid atmospheric heating, ensuring core temperatures stabilize at 600-800°C while dissipating kilowatts-scale waste heat solely by radiation.[62] Hybrid approaches integrate nuclear heat for both power and precise thermal control, such as using RTG waste heat via heat pipes or conductive coupling to warm sensitive instruments, as studied for enhanced efficiency in shadowed lunar or planetary landers. In reactors, NaK's low neutron absorption cross-section preserves fuel integrity, but requires careful handling due to reactivity with water and solidification risks, addressed through alloying and redundant pumps. Empirical data from 30+ U.S. RTG missions show thermal systems maintaining >95% power retention over decades, underscoring nuclear sources' superiority for autonomous thermal homeostasis in non-solar environments compared to resistive heaters dependent on variable electrical input.[60][62]Enabling deep-space scientific missions

Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), powered by the decay of plutonium-238, supply continuous electrical power for deep-space missions where solar irradiance falls to impractically low levels, such as 4% of Earth's at Jupiter and 1% at Saturn.[3] These systems convert thermal energy from radioactive decay—approximately 0.56 watts per gram of plutonium-238—into electricity via thermocouples, yielding specific powers of 3–5 watts per kilogram and operational lifespans exceeding decades without mechanical parts or sunlight dependence.[58] This autonomy has enabled orbiters, flybys, and interstellar probes to sustain scientific instruments, telecommunications, and thermal control far beyond the inner solar system, where photovoltaic arrays would require unfeasibly large masses—often 10–100 times heavier for equivalent output—to compensate for diminished flux.[4] Pioneer 10, launched March 2, 1972, utilized four SNAP-19 RTGs delivering 40 watts electrical initially to traverse the asteroid belt and conduct the first flyby of Jupiter on December 3, 1973, marking humanity's initial venture into the outer solar system and eventual heliosphere escape.[31] Similarly, Voyager 1 and 2, launched September 5 and August 20, 1977, respectively, each carried three Multi-Hundred Watt RTGs generating about 470 watts total at mission start, powering encounters with Jupiter (1979), Saturn (1980–1981), Uranus (1986), Neptune (1989), and subsequent interstellar observations persisting over 47 years with power outputs now around 220 watts via decay and efficiency management.[63] These missions yielded unprecedented data on planetary atmospheres, ring systems, magnetospheres, and plasma environments, with Voyager 1 entering interstellar space on August 25, 2012, at 121 AU from the Sun.[5] Subsequent probes amplified this capability: Galileo, launched October 18, 1989, employed two GPHS-RTGs for 300 watts initial power to orbit Jupiter from December 7, 1995, until its atmospheric entry on September 21, 2003, enduring intense radiation belts that would degrade solar alternatives.[5] Cassini, launched October 15, 1997, used three GPHS-RTGs providing 885 watts at launch for 13 years orbiting Saturn, including Huygens' Titan descent on January 14, 2005, and over 300 close Titan flybys revealing subsurface oceans and organic chemistry.[59] New Horizons, launched January 19, 2006, relied on a single GPHS-RTG outputting 240 watts for its Pluto flyby on July 14, 2015, at 39 AU, and Arrokoth encounter in 2019, demonstrating RTG viability for rapid transit to Kuiper Belt objects.[5] Across 24 NASA missions since 1969, RTGs have facilitated such explorations by ensuring power stability against orbital shadows, thermal extremes, and radiation, with failure rates near zero in flight.[5] Emerging missions underscore ongoing dependence: Dragonfly, targeting Titan arrival in 2034, incorporates an MMRTG for 110 watts to power a rotorcraft-lander navigating hazy, low-light conditions unsuitable for solar dominance.[5] Without nuclear systems, these endeavors—probing icy moons, gas giants, and primordial bodies—would face mass penalties, reduced payloads, or mission curtailment, as solar options falter beyond 5 AU due to inverse-square dimming and panel degradation.[64] Historical data affirm RTGs' role in unlocking over 50 years of outer solar system insights, from Pioneer Venus (1978) to interstellar boundaries, prioritizing compact, decay-driven reliability over sunlight variability.[31]Nuclear propulsion for trajectory enhancement

![Kiwi A nuclear thermal rocket engine ground test firing][float-right] Nuclear propulsion systems enhance spacecraft trajectories by leveraging nuclear reactions to achieve higher specific impulse than chemical rockets, enabling reduced transit times, increased payload mass, or extended mission ranges for interplanetary travel. Two primary variants exist: nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP), which directly heats propellant via a fission reactor for expulsion through a nozzle, and nuclear electric propulsion (NEP), which generates electricity from a reactor to power electric thrusters for ionized propellant acceleration. These systems address limitations of chemical propulsion, such as low exhaust velocities around 4.5 km/s, by targeting exhaust velocities of 8-9 km/s for NTP and over 20-50 km/s for NEP, fundamentally altering delta-v capabilities for trajectory optimization.[65][66] NTP development originated in the United States during the 1950s under Project Rover, initiated by the Atomic Energy Commission and led by Los Alamos National Laboratory, focusing on uranium-fueled graphite reactors to heat hydrogen propellant to temperatures exceeding 2,500 K. The subsequent NERVA program, a joint NASA-AEC effort from 1961 to 1973, produced ground-tested engines like the NRX series, achieving specific impulses of approximately 850 seconds—roughly double that of the best chemical engines—and demonstrating reliable restarts and thrust levels up to 334 kN. Despite successful tests, including over 28 reactor firings totaling more than 1.5 hours of operation, the program was terminated in 1973 amid budget constraints and a shift toward the Space Shuttle, preventing spaceflight demonstration.[67][68][69] Revived interest in NTP emerged in the 1980s through programs like Timberwind and resumed in the 2010s for Mars missions, with NASA and the Department of Defense collaborating on designs using low-enriched uranium fuel for non-proliferation compliance. In 2023, NASA partnered with DARPA on the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) initiative, aiming for a 2027 in-space demonstration of a 10-35 kN engine capable of halving Mars transit times to 3-4 months compared to chemical propulsion's 6-9 months, thereby reducing radiation exposure and enabling shorter surface stays. As of 2025, ground testing continues, with fuel element validations confirming performance under vacuum conditions simulating space operation.[70][35][71] NEP systems, in contrast, prioritize efficiency over thrust, employing megawatt-scale reactors—such as historical Soviet TOPAZ designs or conceptual NASA kilopower-derived units—to drive ion or plasma thrusters for continuous low-acceleration trajectories. This enables time-optimal transfers, such as Earth-Mars paths optimized via variable thrust profiles, potentially opening launch windows and delivering greater payload mass with less propellant than NTP or chemical systems. Recent U.S. Space Force efforts through the 2024-established SPAR Institute focus on hybrid chemical-NEP architectures for cislunar and beyond operations, enhancing maneuverability for missions to Saturn or Enceladus by reducing trip times and improving delta-v budgets.[72][73][74] Neither NTP nor NEP has achieved operational spaceflight, with challenges including reactor shielding to protect electronics, propellant storage for long-duration missions, and regulatory hurdles for launch safety. However, trajectory enhancement potential remains compelling: NTP suits high-thrust phases like trans-Mars injection, while NEP excels in spiral-out maneuvers from low Earth orbit or extended heliocentric transfers, collectively promising architectures for human exploration beyond the Moon.[75][76]Advantages Over Alternatives

Superior energy density and autonomy

Nuclear power systems in space, particularly radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) fueled by plutonium-238, provide exceptionally high energy density through the continuous release of decay heat, far surpassing the capabilities of solar arrays and chemical batteries for missions requiring compact, long-term power. Plutonium-238 exhibits a specific power density of 0.57 watts per gram, allowing a modest fuel mass—typically several kilograms—to generate hundreds of watts-thermal, which is converted to electricity at efficiencies of 5-7% via the Seebeck effect.[77] This contrasts sharply with lithium-ion batteries, which offer specific energies of 100-250 watt-hours per kilogram but demand recharging infrastructure and suffer capacity degradation over cycles, imposing mass penalties exceeding tenfold for equivalent total energy delivery in extended missions.[78] System-level specific power for RTGs, such as the Multi-Mission RTG (MMRTG) used in NASA's Perseverance rover launched in 2020, reaches 2.7 W/kg at beginning of life (BOL) for 110 watts electrical output from a 45 kg unit, enabling reliable operation on Mars despite dust-obscured solar conditions that have curtailed prior solar-powered rovers.[78] Solar photovoltaic systems, while achieving higher initial specific powers (up to 184 W/kg at 1 AU), degrade inversely with distance squared from the Sun—reducing to ~1% intensity at Pluto—and require oversized arrays plus batteries for shadowed or nocturnal periods, as evidenced by the mass-intensive setups for Jupiter-orbiting probes like Juno.[78] Fission reactors amplify this advantage for kilowatt-scale needs, with historical designs like the U.S. SNAP-10A delivering 0.5 kW electrical from 435 kg in 1965, yielding specific powers competitive with advanced solar in mass-constrained scenarios but with vastly greater total energy yield over operational lifetimes.[4] Autonomy stems from the passive, maintenance-free nature of nuclear decay, independent of solar flux, orientation, or mechanical components prone to failure. RTGs operate continuously for decades, with power output decaying predictably at ~0.8% annually due to plutonium-238's 87.7-year half-life; the Voyager 1 and 2 probes, launched in 1977, retain functionality from their Multi-Hundred Watt RTGs—initially 158 watts electrical each—after over 47 years, powering instruments at ~24 billion kilometers from Earth as of 2024.[43] Batteries, conversely, exhibit calendar aging and cycle-induced fade, limiting uncrewed missions to years rather than decades without resupply, while solar reliance falters in deep space or planetary shadows, as demonstrated by the 2007 Mars rover Opportunity's solar-induced dormancy during dust storms.[78] This intrinsic self-sufficiency has enabled breakthroughs like the Cassini orbiter's 13-year exploration of Saturn, where RTGs sustained 870 watts BOL across diverse environments unattainable with photovoltaic alternatives.[4]Performance in shadowed or distant environments

Nuclear power systems, particularly radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and fission reactors, provide reliable electricity in environments where solar irradiance is insufficient or absent, such as permanently shadowed craters on planetary bodies or regions far from the Sun.[79] Unlike solar arrays, which depend on direct sunlight and degrade with distance according to the inverse square law, RTGs generate power continuously from plutonium-238 decay heat, independent of solar proximity or orientation.[80] This autonomy has enabled missions to the outer solar system, where solar flux at Jupiter averages 50.5 W/m²—about 3.7% of Earth's 1366 W/m²—dropping further to 15 W/m² at Saturn, 3.7 W/m² at Uranus, and 1.5 W/m² at Neptune.[81] Beyond Jupiter's orbit, solar power becomes impractical due to the massive panel areas required to achieve viable output within spacecraft mass constraints, often exceeding launch capabilities.[82] In shadowed environments, such as the lunar south pole's permanently dark craters containing water ice deposits, solar panels receive zero illumination, rendering them useless for sustained operations.[83] Nuclear fission reactors are proposed for these sites to deliver kilowatts of continuous power for resource extraction and habitat support, with NASA targeting deployment of a 40-kilowatt unit by 2030 to enable Artemis base camps.[84] RTGs have similarly powered Mars rovers like Curiosity, launched in 2011, which maintains operations through dust storms that can reduce solar availability by over 99% for months, as experienced by earlier solar-dependent rovers Opportunity and Spirit.[80] Empirical success in distant realms underscores this performance edge: NASA's Galileo orbiter, launched October 18, 1989, used three RTGs producing 870 watts initially to study Jupiter's system despite solar weakness, operating until 2003.[85] Similarly, Cassini, arriving at Saturn in 2004 after launch in 1997, relied on three RTGs for 13 years of data collection, including Huygens' Titan descent, where solar alternatives would have demanded unfeasible 20-meter panels.[29] These missions demonstrate nuclear systems' causal reliability in low-light conditions, yielding high scientific returns without sunlight dependency, in contrast to solar-limited inner-system probes.[79]

Proven longevity and mission success rates

Radioisotope power systems (RPS), primarily RTGs, have powered 24 NASA missions successfully since 1969, with an unblemished record of power system reliability where no RPS failure has caused mission loss.[5] These systems provide continuous, autonomous power independent of sunlight, enabling extended operations in deep space and shadowed environments. Operational lifetimes frequently surpass design specifications due to the predictable decay of plutonium-238 fuel, which halves every 87.7 years, allowing gradual power decline rather than abrupt failure.[3] Key missions illustrate this longevity:| Mission | Launch Year | Designed Lifetime | Actual Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pioneer 10 | 1972 | 5 years | 30 years |

| Pioneer 11 | 1973 | 5 years | 22 years |

| Voyager 1/2 | 1977 | ~5 years | >47 years (ongoing) |

| Galileo | 1989 | ~8 years | 14 years |

| Ulysses | 1990 | ~5 years | 19 years |

| Cassini | 1997 | ~7 years | 20 years |

| New Horizons | 2006 | ~10 years | >19 years (ongoing) |

| Curiosity | 2011 | ≥14 years | >14 years (ongoing) |

Risks and Empirical Safety Record

Atmospheric launch and re-entry incidents

The primary risks associated with nuclear power systems during atmospheric launch involve potential structural failure of the launch vehicle, which could disperse radioactive fuel if containment is breached, while re-entry incidents stem from uncontrolled orbital decay leading to atmospheric breakup and possible fragmentation of radioisotope generators or reactors.[88] Historical U.S. and Soviet programs experienced a limited number of such events, with empirical outcomes showing variable containment success and minimal public health impacts, though they prompted design enhancements for fuel encapsulation.[4] ![Nimbus B RTG on the ocean floor][float-right] On April 21, 1964, the U.S. Transit 5BN-3 navigation satellite, powered by a SNAP-9A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) containing approximately 1 kilogram of plutonium-238 dioxide, failed to achieve orbit due to a launch vehicle malfunction, re-entering and disintegrating at high altitude over the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[89] The event released the full fuel inventory into the stratosphere, contributing to a detectable but transient increase in global plutonium deposition, estimated at less than 0.015% of total environmental plutonium levels at the time, with no documented human health effects.[90] This incident, the only U.S. space nuclear launch failure resulting in fuel dispersal, led to a policy shift toward general-purpose heat source designs capable of surviving re-entry intact.[61] In contrast, the May 18, 1968, launch of the U.S. Nimbus B-1 weather satellite carrying two SNAP-19 RTGs with plutonium-238 fuel ended in booster failure at about 18.5 kilometers altitude over the Pacific Ocean near California, necessitating range safety destruction.[8] The RTGs separated and sank intact to the ocean floor in the Santa Catalina Channel, containing the fuel without atmospheric release, as verified by post-incident surveys detecting no elevated radiation.[91] Recovery operations retrieved the generators, confirming the robustness of their iridium-clad fuel capsules under impact and saltwater exposure.[92] The most significant re-entry incident occurred on January 24, 1978, when the Soviet Cosmos 954 reconnaissance satellite, equipped with a BES-5 fission reactor fueled by 30-50 kilograms of enriched uranium-235, malfunctioned in orbit and decayed uncontrolled over northern Canada.[93] Reactor coolant sodium-potassium alloy ignited on atmospheric contact, and the core fragmented, scattering radioactive debris across 124,000 square kilometers, with detectable uranium isotopes found in 12 fragments recovered during Operation Morning Light.[94] Ground contamination levels posed no immediate radiological hazard, as verified by joint Canadian-U.S. monitoring, though cleanup costs exceeded $14 million; the Soviet Union compensated Canada $3 million under the 1972 Space Liability Convention.[95] This event highlighted vulnerabilities in Soviet reactor designs lacking full re-entry survival provisions, unlike subsequent U.S. RTG iterations.[91] Other Soviet re-entries, such as Cosmos 1402 in 1983, involved similar RORSAT reactors but resulted in the core impacting the South Atlantic intact, with no confirmed debris release, underscoring improved but inconsistent orbital management practices.[4] Across documented cases, launch and re-entry incidents released less than 2 kilograms of plutonium equivalent in total, far below thresholds causing measurable ecological disruption, though they fueled international scrutiny and safety protocol refinements.[88]In-orbit and surface operational hazards

Operational hazards of nuclear power systems in orbit primarily involve the risk of radioactive material dispersal due to mechanical failures or coolant leaks, though empirical data indicate such events are rare for radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and more prevalent in early fission reactor designs. RTGs, which rely on the passive decay of plutonium-238 without moving parts or coolants, have demonstrated exceptional reliability, with no instances of in-orbit failure causing spacecraft loss or significant radiation release across dozens of missions since the 1960s.[8] In contrast, Soviet RORSAT satellites equipped with BES-5 fission reactors using sodium-potassium (NaK) alloy coolant experienced multiple coolant leaks during core ejection maneuvers, releasing thousands of droplets ranging from millimeters to centimeters in diameter into orbits around 950 km altitude.[96] These NaK droplets, estimated at over 65,000 from 31 missions between 1967 and 1988, pose collision hazards to other satellites due to their reactivity with water or air upon re-entry and potential for fragmentation upon impact, contributing significantly to the space debris population at those altitudes.[97] [98] Fission reactors introduce additional risks from potential loss-of-coolant accidents or unintended criticality, though no such catastrophic radiation releases have occurred during nominal in-orbit operations. For instance, the TOPAZ-I reactors on Cosmos 1818 and Cosmos 1867, tested in 1987 at 800 km orbits, operated for approximately 5 and 11 months before shutdown, with subsequent partial fragmentation of Cosmos 1818 in 2008 generating debris but no confirmed nuclear fuel dispersal.[99] Potential interactions with space debris or micrometeoroids could exacerbate hazards by breaching containment, leading to fission product leakage, but robust design features in modern concepts, such as solid-fuel reactors launched cold, mitigate these by delaying criticality until post-deployment.[4] Radiation from operational reactors or RTGs can interfere with sensitive instruments on the host spacecraft or nearby assets, necessitating shielding, but levels remain below thresholds that compromise mission integrity in documented cases.[100] On planetary surfaces, operational hazards for nuclear systems center on localized radiation exposure, thermal management failures, and potential dispersal during mobility or seismic events, yet RTGs have operated without incident on the Moon and Mars. Lunar RTGs from Apollo missions, such as SNAP-27 on Apollo 12-17, provided reliable power for seismic and heat flow experiments, with no reported releases of plutonium dioxide fuel despite surface impacts or moonquakes.[8] Mars rovers like Curiosity and Perseverance, powered by Multi-Mission RTGs generating about 110 watts from 4.8 kg of plutonium-238, face dust accumulation and temperature extremes but maintain containment integrity, with radiation primarily affecting onboard electronics rather than external release.[101] Fission surface power systems, proposed for future lunar or Martian bases, could risk thermal runaway or neutron activation of regolith if control systems fail, potentially contaminating habitats or scientific sites, though preliminary analyses emphasize fail-safe designs to prevent such outcomes.[102] Overall, surface operations benefit from gravity-assisted containment and isolation from orbital debris, rendering dispersal risks negligible compared to launch phases.[103]Quantitative assessment of historical incidents versus benefits