Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator

View on Wikipedia

The multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is a type of radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) developed for NASA space missions[1] such as the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Energy's Office of Space and Defense Power Systems within the Office of Nuclear Energy. The MMRTG was developed by an industry team of Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne Energy Systems.

Background

[edit]Space exploration missions require safe, reliable, long-lived power systems to provide electricity and heat to spacecraft and their science instruments. A uniquely capable source of power is the radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) – essentially a nuclear battery that reliably converts heat into electricity.[2] Radioisotope power has been used on eight Earth orbiting missions, eight missions to the outer planets, and the Apollo missions after Apollo 11 to the Moon. The outer Solar System missions are the Pioneer 10 and 11, Voyager 1 and 2, Ulysses, Galileo, Cassini and New Horizons missions. The RTGs on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have been operating since 1977.[3] In total, over the last four decades, 26 missions and 45 RTGs have been launched by the United States.

Function

[edit]Solid-state thermoelectric couples convert the heat produced by the natural decay of the radioisotope plutonium-238 to electricity.[4] The physical conversion principle is based on the Seebeck effect, obeying one of the Onsager reciprocal relations between flows and gradients in thermodynamic systems. A temperature gradient generates an electron flow in the system. Unlike photovoltaic solar arrays, RTGs are not dependent upon solar energy, so they can be used for deep space missions.

History

[edit]In June 2003, the Department of Energy (DOE) awarded the MMRTG contract to a team led by Aerojet Rocketdyne. Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne Energy Systems collaborated on an MMRTG design concept based on a previous thermoelectric converter design, SNAP-19, developed by Teledyne for previous space exploration missions.[5] SNAP-19s powered Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 missions[4] as well as the Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers.

Design and specifications

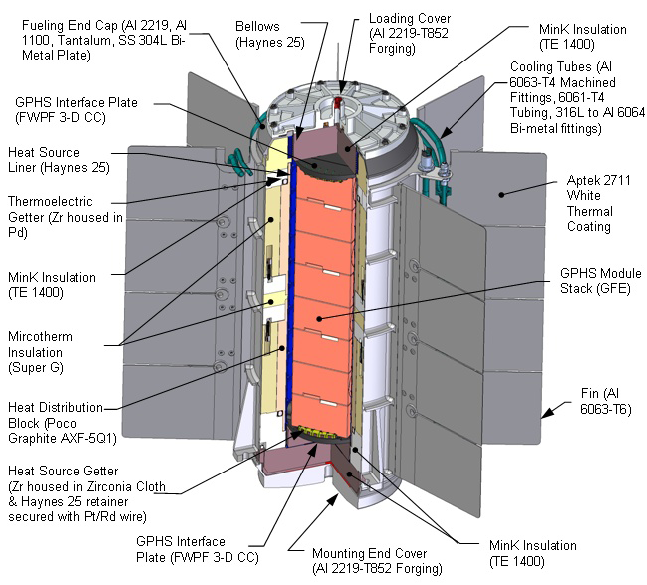

[edit]The MMRTG is powered by eight Pu-238 dioxide general-purpose heat source (GPHS) modules, provided by the US Department of Energy (DOE). Initially, these eight GPHS modules generate about 2 kW thermal power.

The MMRTG design incorporates PbTe/TAGS thermoelectric couples (from Teledyne Energy Systems), where TAGS is an acronym designating a material incorporating tellurium (Te), silver (Ag), germanium (Ge) and antimony (Sb). The MMRTG is designed to produce 125 W electrical power at the start of mission, falling to about 100 W after 14 years.[6] With a mass of 45 kg[7] the MMRTG provides about 2.8 W/kg of electrical power at beginning of life.

The MMRTG design is capable of operating both in the vacuum of space and in planetary atmospheres, such as on the surface of Mars. Design goals for the MMRTG included ensuring a high degree of safety, optimizing power levels over a minimum lifetime of 14 years, and minimizing weight.[2]

The MMRTG has a length of 66.83 cm (26.31 in), and without the fins it has a diameter of 26.59cm (10.47 in), while with the fins it has a diameter of 64.24cm (25.29 in). The fins themself have a length of 18.83cm (7.41 in) [8]

Usage in space missions

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2023) |

Curiosity, the MSL rover that was successfully landed in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012, uses one MMRTG to supply heat and electricity for its components and science instruments. Reliable power from the MMRTG will allow it to operate for several years.[2]

On February 20, 2015, a NASA official reported that there is enough plutonium available to NASA to fuel three more MMRTGs like the one used by the Curiosity rover.[9][10] One was used by Mars 2020 and its Perseverance rover.[9] The other two have not been assigned to any specific mission or program,[10] and could be available by late 2021.[9]

A MMRTG was successfully launched into space on July 30, 2020, aboard the Mars 2020 mission, and is now being used to supply the scientific equipment on the Perseverance rover with heat and power. The MMRTG used by this mission is the F-2 built by Teledyne Energy Systems, Inc. and Aerojet Rocketdyne under contract with the US Department of Energy (DOE) with a lifespan of up to 17 years.[11]

The upcoming NASA Dragonfly mission to Saturn's moon Titan will use one of the two MMRTGs for which the Aerojet Rocketdyne/Teledyne Energy Systems team has recently received a contract.[12] The MMRTG will be used to charge a set of lithium-ion batteries, and then use this higher-power-density supply to fly a quad helicopter in short hops above the surface of Titan.[13]

Cost

[edit]The MMRTG cost an estimated US$109,000,000 to produce and deploy, and US$83,000,000 to research and develop.[14] For comparison the production and deployment of the GPHS-RTG was approximately US$118,000,000.

See also

[edit]- Advanced Stirling radioisotope generator

- Nuclear power in space

- Radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG)

- Thermoelectric effect:

- Seebeck effect: generating an electrical current from a temperature gradient

- Peltier effect: generating a temperature gradient from an electrical current

- Thomson effect: heating or cooling of a current-carrying conductor with a temperature gradient

References

[edit]- ^ "Radioisotope Power Systems for Space Exploration" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates public domain material from Space Radioisotope Power Systems Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2016-07-05. (pdf) October 2013

This article incorporates public domain material from Space Radioisotope Power Systems Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2016-07-05. (pdf) October 2013

- ^ Bechtel, Ryan. "Radioisotope Missions" (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-01.

- ^ a b SNAP-19: Pioneer F & G, Final Report Archived 2018-04-01 at the Wayback Machine, Teledyne Isotopes, 1973

- ^ "Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) Program Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- ^ "Overview of NASA Program on Development of Radioisotope Power Systems with High Specific Power" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ "Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Request Rejected" (PDF). energy.sandia.gov. Retrieved 2025-07-31.

- ^ a b c Leone, Dan (11 March 2015). "U.S. Plutonium Stockpile Good for Two More Nuclear Batteries after Mars 2020". Space News. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ^ a b Moore, Trent (12 March 2015). "NASA can only make three more batteries like the one that powers the Mars rover". Blastr. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (29 July 2020). "NASA's Mars 2020 rover, Perseverance, set to launch into space Thursday with power source built in Hunt Valley". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Receives Contract for up to Two More MMRTGs for Future Deep Space Exploration Missions". Bloomberg.com. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ ""Dragonfly: NASA's Newest Nuclear Powered Spacecraft"". Beyond NERVA. July 9, 2019. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Werner, James Elmer; Johnson, Stephen Guy; Dwight, Carla Chelan; Lively, Kelly Lynn (July 2016). Cost Comparison in 2015 Dollars for Radioisotope Power Systems -- Cassini and Mars Science Laboratory (Report). doi:10.2172/1364515. OSTI 1364515.

External links

[edit]Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Operating Principle

The operating principle of the Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) relies on the Seebeck effect, in which a voltage is generated across the junctions of two dissimilar semiconductor materials when a temperature difference is applied.[6] This thermoelectric conversion process directly transforms thermal energy from radioactive decay into electrical power without any mechanical intermediaries.[7] In the MMRTG, the basic building block is the unicouple, consisting of pairs of p-type and n-type thermoelectric legs connected electrically in series and thermally in parallel. The p-type legs are segmented from tellurium-antimony-germanium-silver (TAGS) at higher temperatures and lead-tin-telluride (PbSnTe) at lower temperatures, while the n-type legs use lead telluride (PbTe).[8] These legs form hot junctions maintained at approximately 800 K by the heat source and cold junctions typically at 400–500 K in planetary atmospheres or lower in vacuum, cooled by the spacecraft environment or fins.[7][9] The temperature gradient drives charge carriers—holes in p-type material and electrons in n-type material—from the hot to cold ends, creating a net voltage across each unicouple. Multiple unicouples are arranged in a modular array to scale the output power.[6] The overall architecture of the MMRTG channels heat from plutonium-238 decay through the general-purpose heat source modules to hot shoes that contact the hot junctions of the thermoelectric couples.[7] The resulting electricity is collected via wiring from the cold-side interconnects and conditioned to provide a stable 28 V DC output to the spacecraft power bus.[8] This solid-state design ensures reliable operation in extreme environments, as the conversion occurs passively through conduction.[6] The efficiency of thermoelectric conversion in the MMRTG is governed by the maximum efficiency formula for a generator operating between hot temperature and cold temperature : where is the thermoelectric figure of merit ( is the Seebeck coefficient, is electrical resistivity, and is thermal conductivity), and is the mean temperature.[10] This derivation accounts for the Carnot efficiency limit modified by material properties, with the second factor representing the device optimization for load matching. For the MMRTG's materials, typically ranges from 0.7 to 1.0 across operating temperatures, yielding an overall system efficiency of about 6%. The MMRTG's design features no moving parts, enabling silent and maintenance-free operation, and it functions independently of sunlight or atmospheric conditions, making it ideal for deep-space missions.[6]Radioisotope Heat Source

The radioisotope heat source in the Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) utilizes plutonium-238 (Pu-238), an isotope selected for its alpha decay process, which emits primarily helium nuclei and produces stable uranium-234 (U-234) as the decay product, generating reliable thermal energy without significant gamma radiation.[13] Pu-238 has a half-life of 87.7 years, enabling long-term power generation suitable for extended space missions.[13] Its decay yields approximately 0.57 watts of thermal power per gram, providing a high specific power density that minimizes the mass required for substantial heat output.[14] The fuel is fabricated as plutonium dioxide (PuO2) in the form of ceramic pellets, with a total mass of about 4.8 kilograms per MMRTG to achieve the necessary thermal capacity.[1] Each pellet is encapsulated within an iridium alloy cladding to contain the radioactive material and withstand high temperatures exceeding 800°C during operation.[15] These fueled clads are assembled into General Purpose Heat Source (GPHS) modules, the core building blocks of the heat source, with eight modules integrated into each MMRTG.[1] Each GPHS module houses four PuO2 pellets, arranged in a stacked configuration, and is further protected by a graphite impact shell for structural integrity during potential launch accidents or atmospheric reentry, along with a lightweight aeroshell for additional shielding.[16] This modular design ensures the fuel remains contained under extreme conditions while delivering consistent heat.[15] At the beginning of the mission, the full array of GPHS modules provides a nominal thermal output of approximately 2,000 watts, derived directly from the ongoing alpha decay of Pu-238.[17] Pu-238 is produced by irradiating neptunium-237 (Np-237) targets with neutrons in high-flux nuclear reactors, followed by chemical separation to isolate the desired isotope, with final processing conducted at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.[18] Production efforts faced significant shortages after the Cold War era, when U.S. facilities ceased large-scale manufacturing in the late 1980s, leading to limited stockpiles that constrained NASA mission planning until restarts in the 2010s.[19]Development History

Pre-MMRTG Systems

The development of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) began in the 1960s under NASA's Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power (SNAP) program, with early designs like the SNAP-19 providing foundational technology for space power systems. The SNAP-19 RTG, operational since the late 1960s, generated approximately 28-42 watts of electrical power depending on the mission configuration and was fueled primarily by plutonium-238 (Pu-238), though some earlier SNAP variants utilized strontium-90 (Sr-90) for terrestrial or low-power applications. It powered the Nimbus III meteorological satellite in 1969, the Pioneer 10 and 11 deep-space probes launched in 1972 and 1973, and the Viking 1 and 2 Mars landers in 1976, demonstrating reliability in diverse orbital and planetary environments over decades.[6] Building on this, the Multi-Hundred Watt (MHW) RTG emerged in the 1970s as a higher-capacity system, delivering about 158 watts of electrical power from a thermal input of roughly 2,400 watts, also using Pu-238 fuel. Designed for extended deep-space missions, the MHW RTG equipped the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft launched in 1977, enabling their ongoing operations beyond the heliosphere more than 45 years later, as well as the Lincoln Experimental Satellites 8 and 9 in 1976. These units featured improved heat source encapsulation for safety and efficiency, marking a step toward more robust power generation for outer solar system exploration.[6][20] The General Purpose Heat Source RTG (GPHS-RTG), introduced in the 1980s, represented the pinnacle of pre-MMRTG designs, producing approximately 300 watts of electrical power through lead telluride/tin telluride (PbTe/SnTe) thermocouples and incorporating 18 general purpose heat source (GPHS) modules fueled by Pu-238. This configuration supported key missions including Galileo (launched 1989 with two units), Ulysses (1990 with one), Cassini (1997 with three), and New Horizons (2006 with one), providing consistent power for long-duration outer planet and heliospheric studies. However, the GPHS-RTG's fixed design was optimized for vacuum environments, relying on radiative cooling without accommodations for atmospheric heat dissipation, such as on Mars, limiting its versatility across mission profiles.[6][21] Pre-MMRTG systems faced inherent constraints that spurred evolution toward more adaptable designs. Their single-mission tailoring—such as specific thermal management for deep-space vacuum—precluded reuse for varied thermal regimes, like planetary atmospheres requiring convective cooling. Production of these RTGs halted after the New Horizons mission in 2006, exacerbated by the cessation of U.S. Pu-238 fabrication in 1988 following the Cold War, which depleted stockpiles and necessitated a standardized, multi-mission approach for future reliability and efficiency. The MMRTG emerged as the successor to address these gaps in versatility and supply chain stability.[22][14][23]MMRTG Development

The Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) development began in 2003 as a collaborative effort between NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to produce a flexible successor to the General-Purpose Heat Source RTG (GPHS-RTG) for diverse space applications. The project was awarded to a contractor team led by Boeing Rocketdyne (subsequently acquired and rebranded as Aerojet Rocketdyne) in partnership with Teledyne Energy Systems, focusing on enhancing adaptability for missions ranging from planetary landers to deep-space probes.[24][6] Central design objectives emphasized multi-mission versatility, including operation in both vacuum and atmospheric conditions, with a minimum electrical output of 110 watts at the beginning of the mission and a guaranteed operational life of at least 14 years to support extended scientific investigations.[1][25] These goals built on prior RTG technologies while addressing limitations in prior systems for broader environmental compatibility. Major milestones included the completion of qualification unit testing in 2007, which validated the design under simulated mission stresses. The first flight unit was delivered in 2011 for integration onto NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover ahead of its launch.[25] Development incorporated rigorous testing phases, such as vibration and thermal vacuum simulations to replicate launch and space conditions, along with electromagnetic interference/compatibility (EMI/EMC) assessments conducted at NASA Glenn Research Center; plutonium-238 fuel loading and final integration occurred at DOE's Idaho National Laboratory to ensure nuclear safety and performance.[26][3] As of 2025, three MMRTG units have been fully assembled and qualified, with two deployed on the Curiosity and Perseverance Mars rovers; a fourth unit is in production for the Dragonfly mission to Titan, supported by DOE's restarted plutonium-238 production program, which is scaling up to full operational capacity of 1.5 kg per year by 2026 to sustain ongoing and future radioisotope power needs.[27][28]Design and Construction

Key Components

The Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) features a cylindrical physical structure designed for robust integration into spacecraft systems, with overall dimensions of 64.2 cm in diameter (fin-tip to fin-tip) and 66.8 cm in length, resulting in a dry mass of 43.6 kg.[2] This compact form factor accommodates the internal heat source, conversion elements, and thermal management hardware while minimizing launch mass penalties. The core heat providers consist of eight plutonium-238 general-purpose heat source (GPHS) modules arranged linearly within the central assembly.[17] The outer housing is constructed from a lightweight aluminum alloy cylinder that encases the internal components, providing structural integrity and electromagnetic shielding. Attached to this housing are eight radial graphite fins, which serve as the primary heat rejection surfaces by radiating excess thermal energy into space. To prevent unwanted heat loss and protect sensitive internals from thermal gradients, the housing is insulated with Min-K aerogel, a high-performance silica-based material that offers low thermal conductivity in vacuum environments.[29][30] At the heart of the power conversion system is the thermocouple array, comprising 768 individual unicouples organized into 128 series-connected strings. Each unicouple utilizes lead telluride (PbTe) material on the hot side for thermal stability at elevated temperatures and tellurium-antimony-germanium-silver (TAGS-85) alloy on the cold side, enabling improved conversion performance compared to earlier RTG designs that relied solely on silicon-germanium couples. These unicouples are mounted between hot and cold shoes to form 16 thermoelectric modules, ensuring efficient heat flow across the temperature differential.[31][8] Heat transport within the MMRTG is managed through a network of sodium-filled Inconel alloy tubes that conduct thermal energy from the GPHS modules to the hot shoes of the thermocouple array, leveraging the high thermal conductivity and compatibility of sodium as a working fluid in a wickless heat pipe configuration. On the cold side, additional heat pipes distribute rejected heat uniformly across the aluminum cold frame and graphite fins, maintaining consistent junction temperatures and preventing hotspots that could degrade performance. This integrated thermal pathway ensures reliable operation across varying mission environments.[32][33] The electrical system delivers a nominal 28 V DC output directly compatible with spacecraft buses, incorporating internal voltage regulators to stabilize fluctuations from the thermoelectric conversion process and electromagnetic interference filters to suppress noise and ensure clean power delivery to onboard electronics. These components are hermetically sealed within the housing to protect against vacuum exposure and radiation.[34][35]Safety Features

The General Purpose Heat Source (GPHS) module serves as the primary safety element in the Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG), employing a multi-layer containment system to safeguard the plutonium-238 dioxide (PuO₂) fuel pellets against release during nominal operations and potential accidents. Each GPHS module encases four PuO₂ pellets within iridium alloy cladding, which has a high melting point of approximately 2446 °C (2719 K), ensuring structural integrity under extreme thermal loads while blocking alpha particle emissions from the fuel.[36] Surrounding the clads are two graphite impact shells constructed from fine weave pierced fabric (FWPF) graphite, which fracture controllably to absorb kinetic energy, providing protection equivalent to surviving impacts at velocities around 55 m/s without compromising the inner containment.[37] Additional layers of carbon-bonded carbon fiber insulation and a reentry aeroshell further enhance robustness, collectively forming a design that prioritizes fuel retention over 99.9% in worst-case scenarios.[38] Launch safety qualifications for the MMRTG adhere to the standards outlined in 10 CFR 71 for radioactive material packaging, encompassing hypothetical accident conditions such as a 30-minute exposure to fires reaching 1100 K (827 °C) and atmospheric reentry with peak ablation temperatures up to 1700 K (1427 °C). During fire tests, the iridium cladding and graphite components maintain containment without fuel release, while reentry simulations demonstrate that the aeroshell erodes predictably to shield the graphite shells and clads from aerodynamic heating.[36] These features minimize radiological risks during ascent, potential explosion fragments, or inadvertent reentry, with probabilistic risk assessments confirming expected public exposure below 0.0001 mSv from any single launch.[38] The PuO₂ fuel incorporates a fissile penalty mechanism, consisting of non-weapons-grade plutonium enriched to over 93% Pu-238 with minimal Pu-240 content, resulting in low spontaneous fission rates and negligible neutron emissions that preclude proliferation concerns. In the event of a breach, the ceramic PuO₂ form oxidizes to a stable, low-solubility oxide with reduced chemical toxicity compared to metallic plutonium, fragmenting into large, non-respirable particles that limit environmental dispersal and biological uptake.[36] Extensive testing at Sandia National Laboratories validates these protections, including drop tests from heights simulating over 1000 g accelerations, puncture tests with a 32 kg penetrator at 1.8 m/s, and combined thermal-mechanical simulations replicating launch and reentry environments, all resulting in no detectable plutonium release.[38] The GPHS modules integrate seamlessly into the MMRTG's cylindrical housing, where they are stacked and secured to maintain alignment without compromising individual safety envelopes.[37] For environmental compliance, the MMRTG design supports end-of-mission deep-space disposal to prevent Earth reexposure, while the materials and assembly processes allow for dry-heat microbial reduction sterilization, ensuring adherence to COSPAR planetary protection guidelines for solar system bodies like Mars.[36]Performance Specifications

Power Characteristics

The Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is designed to deliver a minimum of 110 watts (W) of electrical power at the beginning of mission (BOM), with actual flight units providing approximately 125 W electrical and 2000 W thermal power from the decay of plutonium-238 dioxide fuel.[39][1] This output supports a range of mission requirements, such as powering rover systems on planetary surfaces or deep-space probes. The electrical output is provided at a nominal 28 V DC, yielding a current of roughly 4.5 A in standard configuration, and can be adjusted for higher voltage or current by arranging multiple MMRTGs in series or parallel setups.[40][41] The system's overall efficiency in converting thermal to electrical power is approximately 6-7%, representing an enhancement over prior general-purpose heat source radioisotope thermoelectric generators (GPHS-RTGs) through the use of advanced thermocouple materials like lead telluride (PbTe) and telluride-based alloys, combined with improved heat rejection via fin radiators.[17][42] This efficiency allows about 7% of the generated thermal power to be converted to usable electricity, while the majority—around 93%—is dissipated as waste heat primarily through the external fins to maintain optimal thermocouple operating temperatures.[42] The MMRTG demonstrates robust environmental adaptability, functioning reliably in the vacuum of space or thin planetary atmospheres, such as Mars' carbon dioxide environment, where enhanced convective cooling can result in a slight reduction in electrical output compared to pure radiative cooling in vacuum.[43] This design flexibility ensures consistent performance across diverse mission profiles without requiring mission-specific modifications.[6]Lifespan and Degradation

The Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is engineered for a minimum operational lifespan of 14 years, with performance models extending predictions to a 17-year end-of-design-life (EODL) to support extended mission durations.[1][44] This design accommodates the natural decay of its plutonium-238 (Pu-238) fuel, which has a half-life of 87.7 years, resulting in an approximate annual thermal power loss of 0.79% from radioactive decay alone.[45] The Pu-238 decay ensures that thermal output retains roughly 89.5% after 14 years under ideal conditions, though actual electrical power retention is lower due to additional factors, projected at around 80% for the baseline mission profile.[46] No refueling is required, as the sealed system relies entirely on the inherent longevity of the isotope.[1] Degradation in MMRTG performance arises from multiple sources beyond fuel decay. The primary non-fuel contributor is thermocouple aging, driven by high-temperature exposure (approximately 500–600°C on the hot side), which leads to material sublimation, elemental diffusion across junctions, and gradual reduction in thermoelectric efficiency.[46] Radiation damage from alpha particles and neutrons emitted during Pu-238 decay can also induce microstructural changes in the semiconductor materials, further impacting couple performance over time.[47] These effects combine to yield an additional degradation component estimated at 0.5% per year or more, depending on operating environment.[8] Overall, the effective electrical power degradation rate for MMRTGs in Martian conditions, such as those experienced by the Curiosity rover, averages 3.5–4.8% per year, encompassing both fuel and converter losses.[8][48] The temporal evolution of electrical power output, , is modeled approximately as , where years accounts for Pu-238 thermal decay, with superimposed empirical adjustments for non-fuel degradation (e.g., an additional ~0.5% annual factor integrated into the exponent or as a separate term).[8] This hybrid approach, validated through ground testing and in-flight data, predicts a minimum end-of-life output of about 88 W after 14 years from an initial 110 W baseline, though actual projections for specific units may vary slightly based on environmental loads like temperature cycling.[46][49] In operation, MMRTG performance is monitored via onboard telemetry systems that track voltage, current, and temperature across the generator's couples, enabling real-time assessment of degradation trends.[44] For the Curiosity rover's MMRTG (unit F-1), launched in 2011 and operational since 2012, in-flight data through 2023 indicate power output declining to approximately 85–90 W at approximately 11 years of operation, with projections estimating 73 ± 0.4 W at the 13.25-year mark (as of late 2025).[49][50] Similar degradation is expected for the Perseverance rover's MMRTG, which provided ~110 W at landing in 2021.[51] These observations align closely with pre-mission models, confirming the robustness of the degradation predictions and the unit's ability to sustain rover operations well beyond the nominal 14-year design.[44]Mission Applications

Operational Missions

The Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) powers two operational NASA Mars rover missions, enabling extended exploration in environments where solar power is limited by dust accumulation, low sunlight angles, and long nights. The first application was the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission, launched on November 26, 2011, aboard the Curiosity rover, which landed in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012. Equipped with a single MMRTG containing 4.8 kg of plutonium-238 dioxide, the unit generated over 110 W of electrical power at mission start, sufficient to drive the rover's six wheels for mobility across rugged terrain and to operate scientific instruments such as the Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) suite and the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) laboratory.[17] As of November 2025, Curiosity's MMRTG remains fully operational after more than 13 years (over 4,700 Martian sols) on the surface, delivering approximately 105 W of electrical power despite predictable degradation from plutonium decay and minor thermoelectric effects. The generator's excess thermal output, around 2,000 W initially, also provides critical warming to the rover's electronics and mechanisms during extreme cold, with nighttime temperatures dropping to -90°C, preventing thermal contraction issues in components like the robotic arm. No hardware failures or anomalies have been reported with the MMRTG, allowing Curiosity to traverse over 30 km, drill more than 40 rock samples, and investigate ancient habitable environments without power-related mission interruptions.[52][53][54] The second operational use is the Mars 2020 mission, launched on July 30, 2020, with the Perseverance rover landing in Jezero Crater on February 18, 2021. This rover's MMRTG similarly supplies about 110 W of initial electrical power from the same fuel mass, supporting core functions including autonomous navigation, the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) for oxygen production demonstrations, and the collection of 33 rock core samples for caching in preparation for potential Earth return as of July 2025.[55] The power system also charges batteries for the Ingenuity helicopter, which completed 72 flights to scout terrain and test powered flight on Mars before concluding operations in January 2024.[56] Integration of the MMRTG into both rovers presented challenges in thermal management during high-heat atmospheric entry, descent, and landing (EDL), where the generator's robust design maintained integrity amid peak temperatures exceeding 1,000°C on the aeroshell. Power allocation strategies further optimized performance, such as directing roughly 100 W to propulsion systems for traversing slopes up to 30 degrees and reserving about 10 W for high-gain antenna communications with Earth via orbiters. These missions highlight the MMRTG's role in achieving unprecedented long-duration surface operations, far surpassing solar-powered predecessors like Opportunity, which lasted 15 years but were constrained by dust storms and seasonal power dips.[57][58]Future Missions

The Dragonfly mission, scheduled for launch in July 2028, will utilize a single Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) to power its rotorcraft-lander on Saturn's moon Titan.[59] Operating in Titan's extreme cold environment, with surface temperatures averaging around -179°C, the MMRTG will provide approximately 110 watts of electrical power at the beginning of the mission while also supplying essential heat for avionics, flight systems, and scientific instruments.[60] This configuration enables the autonomous rotorcraft to explore multiple sites across Titan's surface, investigating prebiotic chemistry and habitability.[61] For the proposed Mars Sample Return (MSR) campaign, targeting launches in the late 2020s or early 2030s, NASA is evaluating architectures that incorporate radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), potentially including up to two MMRTGs, to power key elements such as the Sample Retrieval Lander and Mars Ascent Vehicle.[62] These units would replace solar panels on the lander to ensure reliable operation during Martian dust storms and provide thermal management for the ascent vehicle and sample relay orbiter, supporting the retrieval and launch of Perseverance rover samples into orbit for Earth return.[63] This shift to radioisotope power aims to simplify operations and enhance mission robustness in Mars' variable environment.[64] Other proposed applications for MMRTGs include outer planet missions beyond Titan, such as potential probes to Uranus or Neptune's moons, where solar power diminishes significantly, and backup options for Jupiter system explorers like the Europa Clipper, which ultimately selected solar arrays but considered RTGs for sustained operations in the planet's intense radiation belts.[65] Studies are also underway for lunar applications, particularly to provide power during the 14-day lunar night when solar options fail, drawing on historical RTG performance from Apollo-era SNAP-27 units to assess MMRTG viability on the Moon's surface.[66] To meet the demands of these future missions, NASA is developing the enhanced MMRTG (eMMRTG), an upgraded version incorporating skutterudite-based thermoelectric materials for improved efficiency.[67] This design preserves the MMRTG's form factor and interfaces while achieving over 25% higher power output at mission start and up to 50% more at end-of-life compared to the baseline model, enabling longer-duration operations in deep space.[68] A key challenge for expanding MMRTG use is the limited supply of plutonium-238 fuel, with NASA and the Department of Energy targeting production of 1.5 kg per year by 2026 to support multiple missions through the 2030s.[27] This ramp-up, currently exceeding halfway to goal, is essential for sustaining radioisotope power systems amid growing interest in outer solar system and shadowed lunar exploration.[69]Production and Economics

Manufacturing Overview

The manufacturing of the Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is a highly specialized process coordinated by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and NASA, involving secure facilities to handle radioactive materials and ensure mission reliability. The DOE's Idaho National Laboratory (INL) leads fuel assembly and final integration at its Materials and Fuels Complex in Idaho Falls, Idaho, where plutonium-238 (Pu-238) heat sources are incorporated into the generator. Lockheed Martin supports system integration aspects, with operations based in Kennewick, Washington, contributing to the overall assembly workflow for non-nuclear components.[70][3] Pu-238 fabrication begins at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), where neptunium-237 targets are irradiated in the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) to produce the isotope; production restarted in 2015 with an initial investment of approximately $150 million to reestablish the supply chain for space missions. The resulting Pu-238 dioxide is processed into fuel pellets at ORNL, encased in protective iridium clads at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and shipped to INL for further assembly. At INL, General Purpose Heat Source (GPHS) modules—each containing four fuel clads—are welded and encapsulated in graphitic carbon liners within sealed inert-atmosphere gloveboxes to minimize oxidation and contamination risks. These modules provide thermal and structural protection during launch and operation.[28][71][70] The unfueled MMRTG converter assembly, including the thermoelectric elements, is delivered to INL from the manufacturer. Thermocouple strings, composed of lead-telluride unicouples, are integrated under controlled vacuum conditions to simulate space environments and verify electrical performance. Final fueling involves inserting eight GPHS modules into the converter housing within gloveboxes, followed by sealing and initial performance checks using non-nuclear mockups to qualify handling and vibration loads without risking the radioactive fuel. Safety features, such as impact-resistant clads, are verified during these steps to prevent release under accident scenarios.[70][72] Quality assurance adheres to ISO 9001 standards for process control and includes 100% non-destructive testing, such as X-ray radiography of fuel clads to detect defects and helium mass spectrometry for leak checks. Vibration qualification testing follows NASA-STD-7002, subjecting the unit to quasi-static loads up to 25g and random vibration profiles to 0.2 g²/Hz, ensuring structural integrity for launch. Additional tests cover mass properties (target <46.5 kg), magnetic fields (<25 nT at 1 m), and thermal vacuum performance at 10⁻⁶ Torr to confirm power output stability.[73][70] Production is constrained by Pu-238 availability, limited to 1-2 units per year, with three MMRTGs completed by 2025 for missions including Mars Science Laboratory, Perseverance, and a spare unit. The modular GPHS design facilitates scalability, supporting increased output as Pu-238 production ramps to 1.5 kg annually by 2026 via expanded HFIR operations.[28][74]Cost Factors

The per-unit cost of a flight-qualified Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is approximately $109 million in 2015 dollars, encompassing design, fabrication, assembly, and integration for missions such as the Mars Science Laboratory.[75] This figure includes the plutonium-238 (Pu-238) fuel, which accounts for roughly $40 million due to the 4.8 kg quantity required and production expenses of about $8,800 per gram.[76] The overall MMRTG development program incurred costs of about $83 million from 2003 to 2007, covering the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and contractor efforts, though total program expenses across NASA and DOE contributions exceeded this when including facilities and oversight.[75] Major cost drivers for the MMRTG stem from Pu-238 production challenges, including scarcity following the halt of U.S. manufacturing in 1988 until its restart in 2015, which necessitates specialized irradiation and chemical processing at DOE facilities.[77] Additional expenses arise from rare materials such as iridium cladding for fuel pellets to withstand high temperatures and corrosion, as well as telluride antimony germanium silver (TAGS) alloys for the thermoelectric unicouples.[78] Qualification and environmental testing, including vibration, thermal vacuum, and radiological safety assessments, further contribute significantly, often comprising a substantial portion of per-unit outlays.[75] Compared to predecessors like the General Purpose Heat Source RTG (GPHS-RTG), the MMRTG offers similar economics at $109 million per unit versus $118 million (2015 dollars adjusted), but with fewer heat source modules (eight versus eighteen) for multi-mission flexibility.[75] It proved less costly than the Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generator (ASRG), whose flight development ballooned to $446 million before cancellation in 2013 amid budget constraints, despite potential long-term efficiency gains; however, MMRTGs remain more expensive than solar arrays for inner solar system missions where sunlight is abundant.[79] Funding for MMRTG production and Pu-238 supply is shared between NASA and DOE, with NASA covering the majority—about $50 million annually since 2014 for infrastructure and operations—though early efforts saw overruns and delays pushing full Pu-238 scaling to no earlier than 2025.[77] Accounting for inflation, MMRTG unit costs are projected to reach around $130 million in 2025 dollars, reflecting ongoing investments in supply chain reliability.[80] These elevated expenses constrain mission frequency to roughly one every four years, as a single MMRTG can consume 9 percent of a New Frontiers-class budget (~$850 million), yet the device's 14-year minimum lifespan and reliability in extreme environments provide economic justification over repeated battery or solar system replacements for outer planet or shadowed operations.[77]References

- https://mars.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/files/mep/MMRTG_Jan2008.pdf

- https://ntrs.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/api/citations/20160001769/downloads/20160001769.pdf