Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

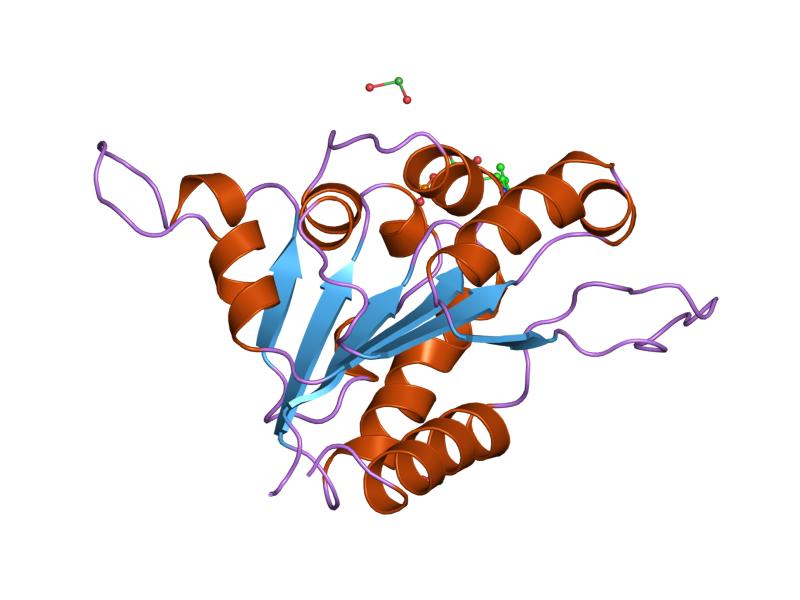

Flavoprotein

View on Wikipedia| Flavoprotein | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

the fmn binding protein athal3 | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Flavoprotein | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02441 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003382 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1e20 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Flavoproteins are proteins that contain a nucleic acid derivative of riboflavin. These proteins are involved in a wide array of biological processes, including removal of radicals contributing to oxidative stress, photosynthesis, and DNA repair. The flavoproteins are some of the most-studied families of enzymes.

Flavoproteins have either FMN (flavin mononucleotide) or FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide) as a prosthetic group or as a cofactor. The flavin is generally tightly bound (as in adrenodoxin reductase, wherein the FAD is buried deeply).[1] About 5-10% of flavoproteins have a covalently linked FAD.[2] Based on the available structural data, FAD-binding sites can be divided into more than 200 different types.[3]

90 flavoproteins are encoded in the human genome; about 84% require FAD and around 16% require FMN, whereas 5 proteins require both.[4] Flavoproteins are mainly located in the mitochondria.[4] Of all flavoproteins, 90% perform redox reactions and the other 10% are transferases, lyases, isomerases, ligases.[5]

Discovery

[edit]Flavoproteins were first mentioned in 1879, when they isolated as a bright-yellow pigment from cow's milk. They were initially termed lactochrome. By the early 1930s, this same pigment had been isolated from a range of sources, and recognised as a component of the vitamin B complex. Its structure was determined and reported in 1935 and given the name riboflavin, derived from the ribityl side chain and yellow colour of the conjugated ring system.[6]

The first evidence for the requirement of flavin as an enzyme cofactor came in 1935. Hugo Theorell and coworkers showed that a bright-yellow-coloured yeast protein, identified previously as essential for cellular respiration, could be separated into apoprotein and a bright-yellow pigment. Neither apoprotein nor pigment alone could catalyse the oxidation of NADH, but mixing of the two restored the enzyme activity. However, replacing the isolated pigment with riboflavin did not restore enzyme activity, despite being indistinguishable under spectroscopy. This led to the discovery that the protein studied required not riboflavin but flavin mononucleotide to be catalytically active.[6][7]

Similar experiments with D-amino acid oxidase[8] led to the identification of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a second form of flavin utilised by enzymes.[9]

Examples

[edit]The flavoprotein family contains a diverse range of enzymes, including:

- Adrenodoxin reductase that is involved in steroid hormone synthesis in vertebrate species, and has a ubiquitous distribution in metazoa and prokaryotes[1]

- Cytochrome P450 reductase that is a redox partner of cytochrome P450 proteins located in endoplasmic reticulum[10][11]

- Epidermin biosynthesis protein, EpiD, which has been shown to be a flavoprotein that binds FMN. This enzyme catalyses the removal of two reducing equivalents from the cysteine residue of the C-terminal meso-lanthionine of epidermin to form a --C==C-- double bond[12]

- The B chain of dipicolinate synthase, an enzyme which catalyses the formation of dipicolinic acid from dihydroxydipicolinic acid[13]

- Phenylacrylic acid decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.102), an enzyme which confers resistance to cinnamic acid in yeast[14]

- Phototropin and cryptochrome, light-sensing proteins[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hanukoglu I (2017). "Conservation of the Enzyme-Coenzyme Interfaces in FAD and NADP Binding Adrenodoxin Reductase-A Ubiquitous Enzyme". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 85 (5): 205–218. Bibcode:2017JMolE..85..205H. doi:10.1007/s00239-017-9821-9. PMID 29177972. S2CID 7120148.

- ^ Abbas, Charles A.; Sibirny, Andriy A. (2011-06-01). "Genetic Control of Biosynthesis and Transport of Riboflavin and Flavin Nucleotides and Construction of Robust Biotechnological Producers". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 75 (2): 321–360. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00030-10. ISSN 1092-2172. PMC 3122625. PMID 21646432.

- ^ Garma, Leonardo D.; Medina, Milagros; Juffer, André H. (2016-11-01). "Structure-based classification of FAD binding sites: A comparative study of structural alignment tools". Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 84 (11): 1728–1747. doi:10.1002/prot.25158. ISSN 1097-0134. PMID 27580869. S2CID 26066208.

- ^ a b Lienhart, Wolf-Dieter; Gudipati, Venugopal; Macheroux, Peter (2013-07-15). "The human flavoproteome". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 535 (2): 150–162. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2013.02.015. PMC 3684772. PMID 23500531.

- ^ Macheroux, Peter; Kappes, Barbara; Ealick, Steven E. (2011-08-01). "Flavogenomics – a genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins". FEBS Journal. 278 (15): 2625–2634. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08202.x. ISSN 1742-4658. PMID 21635694. S2CID 22220250.

- ^ a b Massey, V (2000). "The chemical and biological versatility of riboflavin". Biochemical Society Transactions. 28 (4): 283–96. doi:10.1042/0300-5127:0280283. PMID 10961912.

- ^ Theorell, H. (1935). "Preparation in pure state of the effect group of yellow enzymes". Biochemische Zeitschrift. 275: 344–46.

- ^ Warburg, O.; Christian, W. (1938). "Isolation of the prosthetic group of the amino acid oxydase". Biochemische Zeitschrift. 298: 150–68.

- ^ Christie, S. M. H.; Kenner, G. W.; Todd, A. R. (1954). "Nucleotides. Part XXV. A synthesis of flavin?adenine dinucleotide". Journal of the Chemical Society: 46–52. doi:10.1039/JR9540000046.

- ^ Pandey, Amit V.; Flück, Christa E. (2013-05-01). "NADPH P450 oxidoreductase: Structure, function, and pathology of diseases". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 138 (2): 229–254. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.010. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 23353702.

- ^ Jensen, Simon Bo; Thodberg, Sara; Parween, Shaheena; Moses, Matias E.; Hansen, Cecilie C.; Thomsen, Johannes; Sletfjerding, Magnus B.; Knudsen, Camilla; Del Giudice, Rita; Lund, Philip M.; Castaño, Patricia R. (2021-04-15). "Biased cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism via small-molecule ligands binding P450 oxidoreductase". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 2260. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.2260J. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22562-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8050233. PMID 33859207.

- ^ Kupke, T; Stevanović, S; Sahl, H. G.; Götz, F (1992). "Purification and characterization of EpiD, a flavoprotein involved in the biosynthesis of the lantibiotic epidermin". Journal of Bacteriology. 174 (16): 5354–61. doi:10.1128/jb.174.16.5354-5361.1992. PMC 206373. PMID 1644762.

- ^ Daniel, R.A.; Errington, J. (1993). "Cloning, DNA Sequence, Functional Analysis and Transcriptional Regulation of the Genes Encoding Dipicolinic Acid Synthetase Required for Sporulation in Bacillus subtilis". Journal of Molecular Biology. 232 (2): 468–83. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1403. PMID 8345520.

- ^ Clausen, Monika; Lamb, Christopher J.; Megnet, Roland; Doerner, Peter W. (1994). "PAD1 encodes phenylacrylic acid decarboxylase which confers resistance to cinnamic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Gene. 142 (1): 107–12. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90363-8. PMID 8181743.

- ^ Zhuang, Bo; Liebl, Ursula; Vos, Marten H. (2022-05-05). "Flavoprotein Photochemistry: Fundamental Processes and Photocatalytic Perspectives". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 126 (17): 3199–3207. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c00969. ISSN 1520-6106. PMID 35442696. S2CID 248296520.