Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

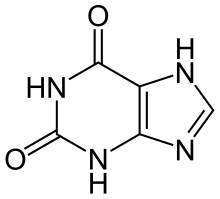

Xanthine

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

3,7-Dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione | |

| Other names

1H-Purine-2,6-dione

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.653 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H4N4O2 | |

| Molar mass | 152.11 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Melting point | decomposes |

| 1 g/ 14.5 L @ 16 °C 1 g/1.4 L @ 100 °C | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Xanthine (/ˈzænθiːn/ or /ˈzænθaɪn/, from Ancient Greek ξανθός xanthós 'yellow' for its yellowish-white appearance; archaically xanthic acid; systematic name 3,7-dihydropurine-2,6-dione) is a purine base found in most human body tissues and fluids, as well as in other organisms.[2] Several stimulants are derived from xanthine, including caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine.[3][4]

Xanthine is a product on the pathway of purine degradation.[2]

- It is created from guanine by guanine deaminase.

- It is created from hypoxanthine by xanthine oxidoreductase.

- It is also created from xanthosine by purine nucleoside phosphorylase.

Xanthine is subsequently converted to uric acid by the action of the xanthine oxidase enzyme.[2]

Use and production

[edit]Xanthine is used as a drug precursor for human and animal medications, and is produced as a pesticide ingredient.[2]

Clinical significance

[edit]Derivatives of xanthine (known collectively as xanthines) are a group of alkaloids commonly used for their effects as mild stimulants and as bronchodilators, notably in the treatment of asthma or influenza symptoms.[2] In contrast to other, more potent stimulants like sympathomimetic amines, xanthines mainly act to oppose the actions of adenosine, and increase alertness in the central nervous system.[2]

Toxicity

[edit]Methylxanthines (methylated xanthines), which include caffeine, aminophylline, IBMX, paraxanthine, pentoxifylline, theobromine, theophylline, and 7-methylxanthine (heteroxanthine), among others, affect the airways, increase heart rate and force of contraction, and at high concentrations can cause cardiac arrhythmias.[2] In high doses, they can lead to convulsions that are resistant to anticonvulsants.[2] Methylxanthines induce gastric acid and pepsin secretions in the gastrointestinal tract.[2] Methylxanthines are metabolized by cytochrome P450 in the liver.[2]

If swallowed, inhaled, or exposed to the eyes in high amounts, xanthines can be harmful, and they may cause an allergic reaction if applied topically.[2]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Caffeine: R1 = R2 = R3 = CH3

Theobromine: R1 = H, R2 = R3 = CH3

Theophylline: R1 = R2 = CH3, R3 = H

In in vitro pharmacological studies, xanthines act as both competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitors and nonselective adenosine receptor antagonists. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors raise intracellular cAMP, activate PKA, inhibit TNF-α synthesis,[2][5][4] and leukotriene[6] and reduce inflammation and innate immunity.[6] Adenosine receptor antagonists[7] inhibit sleepiness-inducing adenosine.[2]

However, different analogues show varying potency at the numerous subtypes, and a wide range of synthetic xanthines (some nonmethylated) have been developed searching for compounds with greater selectivity for phosphodiesterase enzyme or adenosine receptor subtypes.[2][8][7][9][10][11]

| Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R8 | IUPAC nomenclature | Found in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthine | H | H | H | H | 3,7-Dihydro-purine-2,6-dione | Plants, animals |

| 7-Methylxanthine | H | H | CH3 | H | 7-methyl-3H-purine-2,6-dione | Metabolite of caffeine and theobromine |

| Theobromine | H | CH3 | CH3 | H | 3,7-Dihydro-3,7-dimethyl-1H-purine-2,6-dione | Cacao (chocolate), yerba mate, kola, guayusa |

| Theophylline | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 1,3-Dimethyl-7H-purine-2,6-dione | Tea, cacao (chocolate), yerba mate, kola |

| Paraxanthine | CH3 | H | CH3 | H | 1,7-Dimethyl-7H-purine-2,6-dione | Animals that have consumed caffeine |

| Caffeine | CH3 | CH3 | CH3 | H | 1,3,7-Trimethyl-1H-purine-2,6(3H,7H)-dione | Coffee, guarana, yerba mate, tea, kola, guayusa, Cacao (chocolate) |

| 8-Chlorotheophylline | CH3 | CH3 | H | Cl | 8-Chloro-1,3-dimethyl-7H-purine-2,6-dione | Synthetic pharmaceutical ingredient |

| 8-Bromotheophylline | CH3 | CH3 | H | Br | 8-Bromo-1,3-dimethyl-7H-purine-2,6-dione | Pamabrom diuretic medication |

| Diprophylline | CH3 | CH3 | C3H7O2 | H | 7-(2,3-Dihydroxypropyl)-1,3-dimethyl-3,7-dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione | Synthetic pharmaceutical ingredient |

| IBMX | CH3 | C4H9 | H | H | 1-Methyl-3-(2-methylpropyl)-7H-purine-2,6-dione | |

| Uric acid | H | H | H | O | 7,9-Dihydro-1H-purine-2,6,8(3H)-trione | Byproduct of purine nucleotides metabolism and a normal component of urine |

Pathology

[edit]People with rare genetic disorders, specifically xanthinuria and Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, lack sufficient xanthine oxidase and cannot convert xanthine to uric acid.[2]

Possible formation in absence of life

[edit]Studies reported in 2008, based on 12C/13C isotopic ratios of organic compounds found in the Murchison meteorite, suggested that xanthine and related chemicals, including the RNA component uracil, have been formed extraterrestrially.[12][13] In August 2011, a report, based on NASA studies with meteorites found on Earth, was published suggesting xanthine and related organic molecules, including the DNA and RNA components adenine and guanine, were found in outer space.[14][15][16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 9968.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Xanthine, CID 1188". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Spiller, Gene A. (1998). Caffeine. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-2647-8.

- ^ a b Katzung, Bertram G. (1995). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. East Norwalk, Connecticut: Paramount Publishing. pp. 310, 311. ISBN 0-8385-0619-4.

- ^ Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U (February 1999). "Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159 (2): 508–11. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804085. PMID 9927365.

- ^ a b Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ (2005). "Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses". J. Immunol. 174 (2): 589–94. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.589. PMID 15634873.

- ^ a b Daly JW, Jacobson KA, Ukena D (1987). "Adenosine receptors: development of selective agonists and antagonists". Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 230: 41–63. PMID 3588607.

- ^ Daly JW, Padgett WL, Shamim MT (July 1986). "Analogues of caffeine and theophylline: effect of structural alterations on affinity at adenosine receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 29 (7): 1305–8. doi:10.1021/jm00157a035. PMID 3806581.

- ^ Daly JW, Hide I, Müller CE, Shamim M (1991). "Caffeine analogs: structure-activity relationships at adenosine receptors". Pharmacology. 42 (6): 309–21. doi:10.1159/000138813. PMID 1658821.

- ^ González MP, Terán C, Teijeira M (May 2008). "Search for new antagonist ligands for adenosine receptors from QSAR point of view. How close are we?". Medicinal Research Reviews. 28 (3): 329–71. doi:10.1002/med.20108. PMID 17668454. S2CID 23923058.

- ^ Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Gessi S, Borea PA (January 2008). "Adenosine receptor antagonists: translating medicinal chemistry and pharmacology into clinical utility". Chemical Reviews. 108 (1): 238–63. doi:10.1021/cr0682195. PMID 18181659.

- ^ Martins, Z.; Botta, O.; Fogel, M. L.; Sephton, M. A.; Glavin, D. P.; Watson, J. S.; Dworkin, J. P.; Schwartz, A. W.; Ehrenfreund, P. (2008). "Extraterrestrial nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 270 (1–2): 130–136. arXiv:0806.2286. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.270..130M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.026. S2CID 14309508.

- ^ AFP Staff (13 June 2008). "We may all be space aliens: study". AFP. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ Callahan, M. P.; Smith, K. E.; Cleaves, H. J.; Ruzicka, J.; Stern, J. C.; Glavin, D. P.; House, C. H.; Dworkin, J. P. (2011). "Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (34): 13995–8. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813995C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106493108. PMC 3161613. PMID 21836052.

- ^ Steigerwald, John (8 August 2011). "NASA Researchers: DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space". NASA. Archived from the original on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- ^ ScienceDaily Staff (9 August 2011). "DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space, NASA Evidence Suggests". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-08-09.