Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flevoland

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

Flevoland (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈfleːvoːlɑnt] ⓘ) is the twelfth and newest province of the Netherlands, established in 1986, when the southern and eastern Flevopolders, together with the Noordoostpolder, were merged into one provincial entity. It is in the centre of the country in the former Zuiderzee, which was turned into the freshwater IJsselmeer by the closure of the Afsluitdijk in 1932. Almost all of the land belonging to Flevoland was reclaimed in the 1950s and 1960s[5] while splitting the Markermeer and bordering lakes from the IJsselmeer. As to dry land, it is the smallest province of the Netherlands at 1,410 km2 (540 sq mi), but not gross land as that includes much of the waters of the fresh water lakes (meres) mentioned.[6]

Key Information

The province had a population of about 445,000[6] as of January 2023 and consists of six municipalities. Its capital is Lelystad and its most populous city is Almere, which forms part of the Randstad and has grown to become the seventh largest city of the country. Flevoland is bordered in the extreme north by Friesland, in the northeast by Overijssel, and in the northwest by the lakes Markermeer and IJsselmeer. In the southeast, the province borders on Gelderland; in the southwest on Utrecht and North Holland. Outside urban areas, the land in Flevoland is predominantly used for agriculture.

Etymology

[edit]Flevoland was named after Lacus Flevo, a name recorded in Roman sources for a large inland lake at the southern end of the later-formed Zuiderzee;[7] it was mentioned by the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela in his De Chorographia in 44 AD. Due to the slowly rising sea level, a number of lakes gradually developed in the Zuiderzee region, which eventually became contiguous. Pomponius wrote about this: "The northern branch of the Rhine extends to Lake Flevo, which encloses an island of the same name and then flows to the sea like a normal river." Other sources speak of Flevum, which means 'flow'. The process continued and gradually the Zuiderzee arose from this lake. The names "Flevoland" and "Vlieland" have the same origin.

History

[edit]Between 790 and 1250, Lake Flevo became connected with the North Sea. As a result, a number of villages were swallowed by the sea. The newly created inland sea was called Almere.

After a flood in 1916, the decision was made to enclose and reclaim the Zuiderzee, an inland sea within the Netherlands, and thus the Zuiderzee Works started. Other sources[8] indicate other times and reasons, but also agree that in 1932, the Afsluitdijk was completed, which closed off the sea completely. The Zuiderzee was later divided into IJsselmeer (mere at the end of the river IJssel) and Markermeer, planned to be mostly drained to make the Markerwaard. The Markerwaard was never built due to post-War fiscal austerity.[citation needed]

The first land reclaimed was the northeast polder (Noordoostpolder) in 1942. This took in the former small islands Urk and Schokland. It was at first added to the Province of Overijssel.

In the southwest the Flevopolder – larger than the above – was then reclaimed; its northeastern half in 1957 and its southwestern half in 1968.

A key feature of the latter is a narrow body of water kept at three metres below sea level along the former coastline, to stabilize the water table and prevent coastal towns from losing their waterfront and access to the sea. Thus, the Flevopolder became an artificial island joined to the mainland by bridges. The municipalities on the three parts voted to become a province, shortly before this was effected in 1986.

Since that time, Flevoland is the youngest of the 12 provinces of the Netherlands, having been granted this status in 1986. Its current sources of revenue are the cultivation of flowers, farming and tourism. In recent times, it has built many wind turbines as a source of renewable energy.

Geography

[edit]Zuiderzee Works

[edit]Eastern Flevoland (Oostelijk Flevoland or Oost-Flevoland) and Southern Flevoland (Zuidelijk Flevoland or Zuid-Flevoland), unlike the Noordoostpolder, have broad channel between them and the mainland: the Veluwemeer and Gooimeer, respectively, making them, together, the world's largest artificial island.

They are two polders with a joint hydrological infrastructure, with a dividing dike in the middle, the Knardijk, that will keep one polder safe if the other is flooded. The two main drainage canals that traverse the dike can be closed by floodgates in such an event. The pumping stations are the Wortman (diesel powered) at Lelystad-Haven, the Lovink near Harderwijk on the eastern dike and the Colijn (both electrically powered) along the northern dike beside the Ketelmeer.

A new element in the design of Eastern Flevoland is the larger city Lelystad (1966), named after Cornelis Lely, the man who had played a crucial role in designing and realising the Zuiderzee Works. Other more conventional settlements already existed by then; Dronten, the major local town, was founded in 1962, followed by two smaller satellite villages, Swifterbant and Biddinghuizen, in 1963. These three were incorporated in the new municipality of Dronten on 1 January 1972.

Southern Flevoland has only one pumping station, the diesel-powered De Blocq van Kuffeler. Because of the hydrological union of the two Flevolands, it simply joins the other three in maintaining the water level of both polders. Almere relieves the housing shortage and increasing overcrowding on the old land. Its name is derived from the early medieval name for Lake Almere. Almere was to be divided into three major settlements initially; the first, Almere-Haven (1976) situated along the coast of the Gooimeer (one of the peripheral lakes), the second and largest was to fulfill the role of city centre as Almere-Stad (1980), and the third was Almere-Buiten (1984) to the northwest towards Lelystad. In 2003, the municipality made a new Structuurplan which started development of three new settlements: Overgooi in the southeast, Almere-Hout in the east, and Almere-Poort in the West. In time, Almere-Pampus could be developed in the northwest, with possibly a new bridge over the IJmeer towards Amsterdam.

The Oostvaardersplassen is a landscape of shallow pools, islets, and swamps. Originally, this low part of the new polder was destined to become an industrial area. Spontaneous settlement of interesting flora and fauna turned the area into a nature park, of such importance that the new railway line was diverted. The recent decline in agricultural land use will in time make expanding natural land use possible, and connect the Oostvaardersplassen to the Veluwe.

The centre of the polder most closely resembles the prewar polders in that it is almost exclusively agricultural. In contrast, the southeastern part is dominated by extensive forests. Here is also found the only other settlement of the polder, Zeewolde (1984), again a more conventional town acting as the local centre. Zeewolde became a municipality at the same time as Almere, on 1 January 1984, which in the case of Zeewolde meant that the municipality existed before the town itself, with only farms in the surrounding land to be governed until the town started to grow.

-

Northeastern Flevoland: Noordoostpolder

-

Eastern and Southern Flevoland: Flevopolder

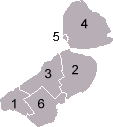

Municipalities

[edit] |

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 177,000 | — |

| 1990 | 211,507 | +19.5% |

| 2000 | 317,206 | +50.0% |

| 2010 | 387,881 | +22.3% |

| 2020 | 423,021 | +9.1% |

| Source: Population dynamics; birth, death and migration per region], CBS StatLine, 4 August 2023[9] | ||

On 1 January 2023, Flevoland had a total population of 444,701 and a population density of 315/km2 (820/sq mi).[1] It is the 2nd least populous province of the Netherlands, with only Zeeland having fewer people. The city of Almere is the most populous municipality in the province.

Religion

[edit]- Not religious (55.2%)

- Protestant Church in the Netherlands (15.5%)

- Catholicism (12.2%)

- Other (9.90%)

- Islam (7.20%)

In 2015, 15.5% of the population belonged to the Protestant Church in the Netherlands while 12.3% was Roman Catholic, 7.2% was Muslim and 9.9% belonged to other churches or faiths. Over half (55.2%) of the population identified as non-religious.

| Municipality | Religious (total) | Protestant | Catholic Church | Islam | Judaism | Hinduism | Buddhism | Others | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protestant Church (PKN) | Dutch Reformed (NHK) | Reformed Churches | ||||||||

| Almere | 38.3 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 13.8 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 7.3 |

| Dronten | 45.1 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 8.5 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 5.7 |

| Lelystad | 36.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 10.2 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 6.8 |

| Noordoostpolder | 52.3 | 12.7 | 7.1 | 9.3 | 14.6 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 7.7 |

| Urk | 97.7 | 21.8 | 14.7 | 45.7 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.8 |

| Zeewolde | 45.7 | 10.2 | 5.5 | 12.1 | 10.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.4 |

Politics

[edit]

Since 2023, the King's Commissioner of Flevoland is Arjen Gerritsen,[12] who is a member of the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD).

The Provincial Council of Flevoland has 41 seats. At the provincial elections in March 2023, the Farmer–Citizen Movement (BBB) became the largest party with 10 seats. The People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) is second largest with 4 seats, after which the Party for Freedom (PVV), Labour Party (PvdA) and Green Left (Dutch: GroenLinks, GL) won 3 seats each. Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats 66 (D66), Party for the Animals (PvdD), Socialist Party (SP), Christian Union (CU), Reformed Political Party (SGP), JA21 and Forum for Democracy (FVD) all won 2 seats each. 50PLUS and Strong Local Flevoland (SLP), a regional party, both won 1 seat each.

Economy

[edit]The gross domestic product (GDP) of the province was €14 billion in 2018, accounting for 1.8% of the Netherlands' economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was €29,500 or 98% of the EU27 average in the same year.[13]

Transport

[edit]Rail

[edit]The Flevopolder is served by the Flevolijn, running from Weesp to Lelystad, and the Hanzelijn, continuing from Lelystad towards Zwolle. The two railways stations of the province with intercity services are Almere Centrum and Lelystad Centrum.

| Trajectory | Railway stations in Flevoland |

|---|---|

| Weesp–Lelystad | North Holland – Almere Poort – Almere Muziekwijk – Almere Centrum – Almere Parkwijk – Almere Buiten – Almere Oostvaarders – Lelystad Centrum |

| Lelystad–Zwolle | Lelystad Centrum – Dronten – Overijssel |

Furthermore, Lelystad Zuid is a planned railway station between Almere Oostvaarders and Lelystad Centrum. It has been partially constructed preceding the opening of the railway in 1988, but construction has been put on indefinite hold because of slower-than-expected development of the city of Lelystad.

Amongst the cities with direct train connections to Flevoland are Amsterdam, Utrecht, The Hague, Zwolle, Groningen, Leeuwarden and Schiphol Airport.

Airport

[edit]There is one airport in the province: Lelystad Airport. A second airport, Noordoostpolder Airport near Emmeloord, was closed in the late 1990s due to town expansion.

Events

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Statistieken provincie Flevoland - Gegevens over meer dan 100 onderwerpen!, AlleCijfers.nl

- ^ "CBS StatLine". opendata.cbs.nl.

- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ How it works : science and technology. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 2003. p. 1208. ISBN 0761473238.

- ^ a b "Regionale kerncijfers Nederland" [Regional key figures Netherlands]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (22 October 2020). "Flevoland". Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-190563-6. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ "Pagina niet gevonden". Provincie Flevoland. 21 February 2019. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013.

- ^ "CBS Statline".

- ^ Helft Nederlanders is kerkelijk of religieus Archived 15 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, CBS, 22 december 2016

- ^ "Gemeente Urk heeft meeste kerkgangers van Nederland". www.omroepflevoland.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 August 2025.

- ^ "Leen Verbeek". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022.

External links

[edit]Flevoland

View on GrokipediaHistory

Etymology

The province's name derives from Lacus Flevo, the Latin term recorded by Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder for a large freshwater lake that existed in the region during antiquity, prior to the medieval silting and transformation into the Zuiderzee inlet.[10] This prehistoric lake, situated at the southern extent of what would become the Zuiderzee, covered much of the central Netherlands lowlands and is attested in classical sources as a distinct body of water separate from the North Sea.[11] When the province was formally established on January 1, 1986, through the consolidation of reclaimed polders including Noordoostpolder, Oostelijk Flevoland, and Zuidelijk Flevoland, the name Flevoland was selected to evoke this ancient hydrological feature, emphasizing the area's origins in land reclamation from the former Zuiderzee (later IJsselmeer).[12] The choice reflects a deliberate historical reference rather than a direct continuation of medieval nomenclature, such as the Aelmare used for the lake in the Middle Ages.[11]Pre-reclamation era

The region comprising modern Flevoland featured prehistoric human activity dating back to the Neolithic period, with the Swifterbant culture (circa 5300–3400 BC) evidencing a gradual shift from foraging to early agriculture and animal husbandry. Archaeological excavations in the former seabed have uncovered settlements with pottery, stone tools, flint implements, remains of domesticated and wild animals, and evidence of cereal cultivation amid wetland environments.[11][13][14] By the Roman era in the 1st century AD, the area lay within Lacus Flevo, a large freshwater lake spanning much of the Low Countries' interior, documented by geographer Pomponius Mela as an estuarine body linked to river systems like the Rhine. This lake persisted into the early Middle Ages as Almere, a brackish-to-freshwater expanse surrounded by peatlands and dunes, supporting sparse habitation on higher grounds and islands.[11][15] The decisive transformation occurred during the St. Lucia's flood of December 13–14, 1287, when a North Sea storm surge overwhelmed coastal barriers, inundating low-lying lands and converting Almere into the Zuiderzee—a saltwater inlet extending roughly 120 km inland and covering expanding areas through subsequent erosion and floods. This event, one of Europe's deadliest natural disasters with estimates of 50,000–100,000 fatalities, submerged prehistoric and medieval landscapes, including villages and farmland, while fostering maritime communities on surviving islets like Urk and Schokland.[16][17] From the late medieval period onward, the Zuiderzee remained a dynamic, shallow sea prone to storm surges, supporting fishing economies and trade but periodically eroding shores and drowning settlements, as evidenced by underwater traces of four medieval villages in the Noordoostpolder area identified through geophysical surveys. Peat extraction and early diking efforts mitigated some losses, yet the inlet's volatility persisted until modern engineering interventions.[18][19]Zuiderzee Works and land reclamation

The Zuiderzee Works, initiated to mitigate flooding risks and expand arable land, formed the foundation for Flevoland's creation by systematically enclosing and draining portions of the former Zuiderzee inlet. Engineer Cornelis Lely first proposed a comprehensive closure and reclamation plan in 1891, envisioning a dike across the inlet to create freshwater lakes and polders for agriculture.[20] [1] The 1916 Zuiderzee flood, which caused extensive damage and over 100 deaths, accelerated parliamentary approval of Lely's revised scheme, with the Zuiderzee Works Act passed on June 14, 1918.[20] Central to the project was the Afsluitdijk, a 32-kilometer barrier dam constructed from 1927 to 1932, linking North Holland to Friesland and transforming the saltwater Zuiderzee into the freshwater IJsselmeer.[20] [21] This enclosure enabled subsequent polder reclamations by allowing controlled drainage, yielding approximately 1,650 square kilometers of new land overall, though environmental concerns later limited full implementation of Lely's original designs.[20] Flevoland's polders—Noordoostpolder, Oostelijk Flevoland, and Zuidelijk Flevoland—accounted for about 970 square kilometers of this reclaimed territory, primarily for farming and urban development.[22] Reclamation of the Noordoostpolder began with dike construction in 1936, followed by pumping out seawater and completion of drainage in 1942, creating 480 square kilometers of fertile clay soil from what had been seabed.[22] [1] Oostelijk Flevoland's 300 square kilometers were enclosed by dikes starting in 1950 and fully drained by 1957, while Zuidelijk Flevoland's 430 square kilometers followed with dike work from 1959 and drainage concluding in 1968; these latter polders incorporated sandy soils better suited to forestry alongside agriculture.[22] [23] The processes involved extensive hydraulic engineering, including ring dikes to isolate polders from the IJsselmeer, windmills and pumps for dewatering, and soil desalinization over years to render the land viable for cultivation.[1] By prioritizing empirical flood control and land productivity over ecological preservation, the works demonstrated causal engineering triumphs but also introduced long-term challenges like subsidence and altered hydrology.[20]Post-reclamation development and provincial formation

Following the reclamation of the Noordoostpolder, which became fully dry on September 9, 1942, development focused on agricultural settlement and infrastructure. The polder, initially administered under a temporary state directorate, was integrated into the province of Overijssel in 1950, with Emmeloord established as its central town between 1943 and 1951 to coordinate farming communities on large-scale plots designed for mechanized agriculture.[24][22] By the mid-1950s, over 400 farms had been allocated, emphasizing dairy, arable crops, and horticulture suited to the clay-rich soils, while the former island of Urk retained semi-autonomous status until its incorporation.[12] The subsequent reclamation of Oostelijk Flevoland began with dyke closure in 1950 and drying by 1957, followed by Zuidelijk Flevoland's dyke in 1959 and full drainage in 1968, expanding the land area for mixed agricultural and urban use to alleviate population pressure in the Randstad conurbation.[22][1] These polders received modern hydrological designs with larger fields, integrated drainage, and bordering lakes for water management, shifting from the denser village patterns of the Noordoostpolder to fewer, more dispersed settlements like Dronten (founded 1962) in the east and Lelystad (established 1967) as the planned administrative hub.[22] Zuidelijk Flevoland prioritized urban expansion, with Almere's first residents arriving in 1976 to house overspill from Amsterdam, growing into a planned city emphasizing high-density housing and green spaces.[12] Administratively, the newer polders operated under direct state oversight via the Rijksdienst voor de IJsselmeerpolders (RIJP) from the 1950s, bypassing immediate provincial attachment to allow coordinated planning across the IJsselmeer area.[1] Municipalities formed progressively, such as Lelystad in 1980 and Almere in 1984, but inter-polder cohesion prompted debates on provincial status amid growing population and economic integration. On January 1, 1986, the Noordoostpolder, Oostelijk Flevoland, and Zuidelijk Flevoland were consolidated into the twelfth province of Flevoland, with Lelystad designated capital, marking the culmination of centralized reclamation efforts into a unified territorial entity.[1][12] This formation enabled localized governance while preserving the polders' engineered landscape for agriculture (dominant in the north and east) and urban-residential functions (concentrated in Almere and Lelystad).[22]Geography

Physical features and polders

Flevoland's physical landscape is dominated by three large polders—Noordoostpolder, Oostelijk Flevoland, and Zuidelijk Flevoland—reclaimed from the Zuiderzee as part of the Zuiderzee Works. These polders constitute a predominantly flat, engineered terrain lying below sea level, with average elevations around 3 meters below NAP (Normaal Amsterdams Peil, approximately mean sea level). The entire province spans 2,412 square kilometers including water bodies, but dry land covers about 1,410 square kilometers, protected by dikes up to 7 meters high and drained by over 1,500 kilometers of ditches and canals per polder in some cases. Soils primarily consist of marine clay, interspersed with sandy patches and peat remnants along edges, fostering fertile agricultural land while requiring constant pumping to prevent flooding.[25][26][7] The Noordoostpolder, the earliest and northernmost, was fully drained by 1942 and encompasses approximately 480 square kilometers. It incorporates elevated remnants of former islands, such as Urk (rising to about 9 meters above NAP) and Schokland (up to 5 meters), creating minor knoll landscapes amid the otherwise uniform flatness. The polder's clay-heavy soils support diverse farming, with drainage systems maintaining water levels at 1.4 meters below surface.[22][27] Oostelijk Flevoland, to the south, was reclaimed in 1957 and covers around 540 square kilometers of similar clay-dominated terrain, designed with grid-patterned fields and integrated woodlands for windbreaks and biodiversity. Its eastern boundary abuts the Veluwe region, contrasting the polder's lowlands with higher sandy hills.[22] Zuidelijk Flevoland, the southern polder completed in 1968 after drainage starting in 1959, measures 430 square kilometers and features internal lakes like the Wolderwijd and borders the Eemmeer and Nijkerkernauw. This area includes planned nature zones such as the Oostvaardersplassen, a 56-square-kilometer wetland reserve, enhancing ecological diversity within the anthropogenic landscape.[28][22] The polders are fringed by the IJsselmeer to the north and Markermeer to the west, with freshwater inflows regulating salinity and supporting fisheries. Subsidence from peat oxidation and consolidation poses ongoing challenges, mitigated by adaptive water management to sustain elevations against sea-level rise.[29]Municipalities and administrative divisions

Flevoland is divided into six municipalities, which constitute its primary administrative divisions and handle local governance, including zoning, infrastructure, and social services. These municipalities—Almere, Dronten, Lelystad, Noordoostpolder, Urk, and Zeewolde—were largely established following the land reclamation projects of the mid-20th century, with Noordoostpolder and Urk predating the province's formal creation on January 1, 1986.[30][7] Lelystad functions as the provincial capital and administrative center, while Almere is the most populous municipality and a key urban hub connected to the Randstad conurbation. The remaining municipalities emphasize agricultural, fishing, and rural development, reflecting the province's polder origins.[12][31] The table below lists the municipalities with their approximate land areas and 2024 population estimates derived from official statistical projections.| Municipality | Land Area (km²) | Population (2024 est.) |

|---|---|---|

| Almere | 129 | 225,000 |

| Dronten | 334 | 44,800 |

| Lelystad | 230 | 84,700 |

| Noordoostpolder | 594 | 47,000 |

| Urk | 5 | 21,000 |

| Zeewolde | 158 | 25,000 |

Demographics and Society

Population dynamics

Flevoland's population has expanded significantly since the province's establishment in 1986, reflecting its origins as reclaimed land developed for settlement. On January 1, 1990, the population stood at 211,507, rising to 317,206 by January 1, 2000, and continuing to increase steadily thereafter.[35] By January 1, 2024, the population reached 447,614, with an estimated end-of-year figure of approximately 450,826, marking consistent annual growth rates around 8.9 per 1,000 inhabitants in recent years.[36] [4] This trajectory positions Flevoland as one of the Netherlands' fastest-growing provinces, with expansion driven primarily by planned urbanization in areas like Almere, serving as a commuter hub for the Randstad region.[37] The province's demographic vitality stems from a young age structure, resulting in relatively high birth rates compared to national averages—10.3 per 1,000 in 2024—coupled with low death rates of around 10.3 per 1,000 in the same year, yielding near-zero natural increase.[36] Net migration has been the dominant growth factor, contributing 3,999 persons in 2024 alone, including both domestic inflows from denser provinces and international arrivals attracted by affordable housing and employment opportunities in agriculture and services.[36] This pattern aligns with Flevoland's role as an overflow area for urban pressure, though growth has moderated slightly amid national trends of slowing overall population expansion outside the Randstad.[38] Projections indicate continued moderate growth, with estimates reaching 456,395 by 2025, supported by ongoing housing development and the province's appeal to families due to its lower density of 323.7 inhabitants per km².[4] Factors such as a fertility rate historically above the European average—around 1.72 children per woman as of 2019—further bolster long-term dynamics, though sustained reliance on migration underscores vulnerabilities to policy shifts in immigration or regional economic balances.[39][36]Ethnic and cultural composition

As of January 1, 2022, approximately 65.5% of Flevoland's population of 434,771 residents were autochtoon, defined as individuals with both parents born in the Netherlands.[40] The remaining 34.5% had a migration background, comprising 10.4% with Western origins (primarily other European countries) and 24.0% with non-Western origins.[40] Among non-Western groups, the largest were those with Surinamese roots (31,399 individuals), followed by Moroccan (12,571), other non-Western countries (43,883, including significant numbers from Indonesia and the Middle East), Dutch Antilles/Aruba (8,513), and Turkish (8,056).[40] This composition reflects Flevoland's relatively high share of non-Western migrants compared to more rural Dutch provinces, driven by affordable housing in growth centers like Almere, which attracts families from urban areas and abroad.[40]| Migration Background Category | Number of Residents (2022) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Autochtoon (Native Dutch) | 284,943 | 65.5% |

| Western | 45,406 | 10.4% |

| Non-Western | 104,422 | 24.0% |

| Total | 434,771 | 100% |

Religion

In Flevoland, 46.3% of persons aged 15 and older identified with a religion in 2021, according to Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) data, compared to a national figure of 49.3%. Among religious adherents, Protestants form the largest group at 19.4%, exceeding the national Protestant share of 15.6%; this elevated proportion stems from orthodox Reformed communities, particularly in municipalities like Urk and parts of Noordoostpolder, which extend the Dutch Bible Belt's influence into the province. Catholics account for 11.7%, lower than the national 23.2%, reflecting limited historical Catholic settlement in the reclaimed polders. Muslims comprise 6.1%, slightly above the national 4.9%, largely concentrated in urban areas such as Almere due to post-reclamation immigration patterns. Other religions, including Hinduism and non-Western Christian denominations, make up 9.2%.[46] Religious involvement remains higher than the national average, with 19.8% attending services at least monthly versus 15.3% nationally; Protestant attendance drives this, bolstered by conservative Calvinist traditions in rural enclaves. Secularization trends mirror national patterns, yet Flevoland's relative youth as a province—formed in 1986 from IJsselmeer polders—has fostered a mosaic of transplanted communities, including evangelical and Pentecostal groups alongside traditional denominations. No single religion dominates provincial policy, but local tensions occasionally arise over issues like Sabbath observance in Urk or mosque constructions in Almere.[46] The non-religious population stands at 53.7%, aligned with broader Dutch dechurching since the 1960s, though Flevoland reports marginally higher religiosity in some CBS regional analyses, attributed to selective migration from faith-stronghold provinces like Overijssel and Gelderland during land reclamation in the 1950s–1970s.[46][47]Government and Politics

Provincial administration and structure

The provincial administration of Flevoland is structured according to the standard framework for Dutch provinces, comprising three primary organs: the Provincial States (Provinciale Staten), the Provincial Executive (Gedeputeerde Staten), and the King's Commissioner (Commissaris van de Koning). The Provincial States serve as the elected legislative assembly, consisting of 39 members who are directly elected by proportional representation every four years; they hold ultimate authority over provincial policy, approve budgets, and oversee the executive.[48][49] The Provincial Executive functions as the daily governing body, responsible for implementing policies, managing administration, and executing decisions of the Provincial States. It is composed of the King's Commissioner, who acts as chairperson, and five elected deputies (gedeputeerden), selected by and accountable to the Provincial States; the executive handles areas such as spatial planning, environmental management, and economic development specific to Flevoland's reclaimed polder landscape.[50] The King's Commissioner, currently Arjen Gerritsen since his appointment in 2023, is appointed by the Dutch government for a six-year term and serves as the representative of the Crown, maintaining political neutrality while chairing both the Provincial States and Executive meetings. This role includes mediating internal disputes, supervising municipal administrations within the province, and acting as a liaison between provincial and national government on matters like infrastructure and water management.[51]Political landscape and elections

The Provincial States of Flevoland, the province's legislative assembly, comprises 41 members elected by proportional representation every four years, concurrently with water board elections.[52] The assembly determines provincial policy on spatial planning, environment, agriculture, and infrastructure, while the executive board (Gedeputeerde Staten) implements decisions under the oversight of the King's Commissioner. Arjen Gerritsen of the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) has served as King's Commissioner since November 1, 2023, appointed by the national government for a six-year term.[53] In the March 15, 2023, provincial elections, the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB) secured the largest share with 10 seats, reflecting strong rural voter support amid national debates over agricultural regulations and nitrogen emissions limits affecting Flevoland's farming sector.[54] Other major parties included the Party for Freedom (PVV) with gains in both rural and urban areas, VVD holding steady, and left-leaning GroenLinks-PvdA alliance retaining urban strongholds in Almere. Voter turnout was approximately 64%, higher than the national average, driven by polarized agrarian issues.[55] The resulting coalition government, comprising BBB, VVD, PVV, Christian Union (CU), and Reformed Political Party (SGP), commands 21 seats and prioritizes balanced agricultural sustainability, housing expansion, and infrastructure without compromising food production.[54] Flevoland's politics exhibit a divide between its polder-based agricultural municipalities, where conservative and agrarian parties like BBB, CU, and SGP dominate due to the province's heavy reliance on farming—accounting for over 20% of the national potato and flower bulb production—and urban centers like Almere, which favor progressive parties emphasizing housing and environmental policies.[56] This rural-urban tension influences debates on land use, with rural areas resisting stringent EU-derived environmental rules that threaten farm viability, while cities push for densification to accommodate population growth exceeding 430,000 residents as of 2023. Provincial elections also indirectly shape national politics, as the States elects Flevoland's share of the Senate.[52]Policy controversies and debates

The management of the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve has been a focal point of policy debate since the early 2000s, centered on the tension between non-interventionist rewilding principles and animal welfare concerns. Established in 1979 as part of Flevoland's polder reclamation, the 56 km² fenced reserve introduced large herbivores like konik horses, red deer, and heck cattle to simulate prehistoric ecosystems, with minimal human interference intended to allow natural population dynamics. Harsh winters, particularly in 2004-2005 and 2017-2018, led to widespread starvation and emaciation, prompting public protests and media coverage depicting scenes of suffering animals, which critics argued violated welfare standards under Dutch animal protection laws.[57][58] In response, a 2018 report by Flevoland's provincial council recommended terminating strict rewilding by authorizing culling of approximately 1,000 deer, permitting recreational hunting from 2019, and exploring introductions of predators like wolves to regulate populations, marking a shift from ecological idealism to pragmatic intervention amid empirical evidence of unsustainable densities exceeding 200 deer per km² in peak years.[59] Proponents of the original policy, including ecologist Frans Vera, defended it as essential for biodiversity restoration, citing increased bird species from 95 in the 1980s to over 250 by 2010, while opponents highlighted the ethical costs and questioned the validity of applying Pleistocene models to a modern, enclosed wetland without migration corridors.[60] Agricultural policies, particularly those addressing nitrogen emissions, have sparked ongoing controversies in Flevoland, a province with intensive livestock and arable farming contributing about 24% of its required national reduction target by 2030 to comply with EU Natura 2000 directives. Triggered by a 2019 Dutch Council of State ruling declaring the national program inadequate due to verified exceedances of critical deposition loads harming protected habitats, provincial plans like the 2021 "Aanpak Stikstof" framework mandate cuts through farm buyouts, emission-efficient technologies, and relocation of high-impact operations, affecting an estimated 10-15% of Flevoland's 1,200 dairy and pig farms.[61] Farmers, organized under groups like Farmers Defence Force, have protested these measures—blocking provincial roads with tractors in 2019 and 2022—arguing they impose disproportionate economic burdens without sufficient evidence of proportional ecological gains, as Flevoland's baseline emissions are lower than in provinces like Noord-Brabant and its Natura 2000 areas are relatively distant from hotspots.[62] Recent assessments indicate nitrogen constraints, combined with electricity grid congestion, threaten over 500,000 housing units nationwide, including Flevoland's growth targets in Almere, fueling debates on prioritizing urban expansion over rural preservation.[63] Provincial coalitions, often balancing green parties like GroenLinks with agrarian interests via CDA, have pursued compromises such as voluntary herd reductions incentivized by €100-200 million in subsidies, though empirical monitoring shows only partial progress toward the 40% national interim goal by 2025, with critics on both sides questioning the feasibility and data integrity of deposition models.[64] Sustainability transitions in Flevoland's agriculture have also generated policy friction, evolving from predominantly economic-oriented frameworks in the 1990s—emphasizing productivity on reclaimed peat and clay soils—to integrated ecological agendas post-2010 that incorporate circular farming and biodiversity metrics. Documents like the 2016-2020 agricultural vision plan reflect this shift, promoting reduced pesticide use and soil health initiatives amid EU pressures, but stakeholders debate the causal links between intensification and environmental degradation, with data indicating Flevoland's yields (e.g., 50-60 tons/ha potatoes) remain high yet vulnerable to climate variability without adaptive tech.[65] These tensions underscore broader provincial efforts to reconcile food production, which accounts for 20% of GDP, with emission targets, often contested in council debates over funding allocations and the reliability of predictive models for long-term viability.[64]Economy

Agriculture and primary sectors

Flevoland's agriculture dominates the primary sector, leveraging 89,000 hectares of large, efficient polder plots reclaimed through the Zuiderzee Works for intensive production.[66] Arable farming prevails, with major crops encompassing seed potatoes—particularly high-quality varieties from the Noordoostpolder exported since 1957 to markets in France, Belgium, and beyond—alongside vegetables, cereals, onions, sugar beets, and flowers.[67] The province yields over 1,000 diverse products, earning designation as Europe's vegetable garden due to its scale and soil fertility.[67] Livestock includes dairy cattle and pigs, though arable output overshadows animal husbandry in economic weight.[12] Flevoland leads the Benelux in organic farming share, with 3.8% of national certified organic operations in 2024, emphasizing sustainable practices amid national trends of farm consolidation—only 70 closures province-wide that year versus thousands nationally.[68][69][70] Innovations bolster productivity, including the Lelystad-based Farm of the Future field lab testing strip cropping, robotics, and data analytics for resilient systems, and devices like the ODD.bot Weed Whacker for chemical-free weed management.[67][71] As the province's largest economic pillar, agriculture drives exports and agribusiness, though it contends with environmental policies prioritizing soil health and biodiversity over pure yield maximization.[67][72]Industry, innovation, and services

Flevoland's industrial sector emphasizes manufacturing, particularly in food processing, high-tech systems, and life sciences, leveraging the province's agricultural base and central location. Key companies include Aviko, a major potato processing firm in Emmeloord, and FrieslandCampina, which operates dairy facilities contributing to the region's export-oriented production.[73] High-tech manufacturing is prominent, with firms like ASM International in Almere specializing in semiconductor equipment, and Verbruggen Palletizing Solutions developing automated agricultural handling systems.[74][75] The sector benefits from international firms such as Toshiba and Bestseller establishing operations, supporting an economy with strong export focus.[76] Innovation in Flevoland centers on agri-tech, sustainable manufacturing, and circular economy practices, facilitated by organizations like Horizon Flevoland, which promotes entrepreneurship through initiatives such as the Smart Innovation Hub in Almere—a collaborative space for startups, educators, and governments offering workspaces and networking.[77] The Green Innovation Hub in Almere fosters public-private partnerships for sustainable urban development, while regional efforts support high-tech systems and materials (HTSM) in agri-food applications.[78] Despite an entrepreneurial spirit, the startup ecosystem remains nascent compared to older Dutch provinces, with growth driven by funds like MKB & Technofonds Flevoland.[79][80] Services dominate employment, with business services, wholesale and retail trade comprising major shares; in Almere alone, these sectors account for significant portions of the 101,000 jobs as of January 2025, alongside healthcare.[81] Province-wide, the 2023 employment rate reached 68.9%, above the national average, with over 259,000 labor market participants, though services like information and communication (NACE J) represent about 6% of employment.[82] Emerging logistics services capitalize on Flevoland's infrastructure, positioning it as a hub for distribution amid ongoing industrial expansion.[83]Housing, real estate, and recent trends

Flevoland's housing market reflects the province's status as the Netherlands' youngest region, characterized by planned urban expansions in cities like Almere and Lelystad to accommodate population growth amid national shortages. The province faces a proportional share of the country's housing deficit, estimated at 396,000 homes nationwide in 2024, driven by insufficient construction relative to demand from immigration, household formation, and economic pressures.[84] In Flevoland, this manifests in competitive demand for available properties, with approximately 15,000 homes sold in 2023, contributing to broader transaction volumes that surged 25.1% quarter-on-quarter in the third quarter of 2024, the highest regional increase.[85][86] Average property values in Flevoland reached €361,566 in 2024, a substantial rise from €75,000 in 1997, underscoring long-term appreciation in a region built on reclaimed land with modern infrastructure.[4] Recent trends indicate accelerating price growth, with existing owner-occupied homes projected to increase by 11% in 2025, outpacing the national average of 8.6%, due to limited supply and proximity to the Randstad economic hub.[87] This escalation aligns with national dynamics, where mortgage rate declines to around 3.78% in 2024 have boosted affordability and sales, though Flevoland's polder-based developments prioritize single-family and terraced homes over high-density apartments.[88] New construction efforts focus on expanding capacity, particularly in Almere, which has been tasked with accommodating 60,000 additional homes alongside infrastructure upgrades to rail and roads.[89] Projects like the first phase of New Brooklyn in Almere, completing 235 residences by 2025, exemplify ongoing developments, with 25 active new-build initiatives reported in the city amid high demand for plots.[90][91] However, national constraints—including nitrogen emission regulations and electricity grid overloads—threaten delays to up to 500,000 planned homes across the Netherlands, potentially impacting Flevoland's pipeline despite its land availability.[92] Lelystad sees slower but steady growth, with self-build options in newer districts addressing affordability for families, though overall permits nationwide fell to 33,300 in early 2025, signaling caution in regional output.[93]Infrastructure and Transport

Road and rail networks

Flevoland's road network features key national motorways including the A6, which spans 102 kilometers from near Amsterdam through the province toward Friesland, and the A27, extending 109 kilometers from Breda to Almere and connecting to Utrecht.[94][95] These highways enable efficient access from major urban centers, with the province prioritizing smooth traffic flow and delay prevention on its main roads.[96] The province maintains about 600 kilometers of roads at speeds of 60, 80, and 100 km/h, supplemented by provincial routes such as the N305 linking Almere to Dronten and the N307 connecting near Lelystad to Kampen.[97] Rail infrastructure centers on the Flevolijn, running from Weesp through multiple Almere stations to Lelystad, with extensions via the Hanzelijn to Zwolle. The Hanzelijn, a 50-kilometer line paralleling parts of the N23 road, opened for passenger services in December 2012, reducing Amsterdam-Zwolle travel times.[98][99] Almere features six stations along this line, while Lelystad Centrum provides intercity connections alongside sprinter services operating up to twice hourly off-peak.[100][101] These networks support regional connectivity in the polder landscape, with straight alignments reflecting planned reclamation topography.[102]Aviation: Lelystad Airport development and challenges

Lelystad Airport, situated in the Flevoland province, was established in 1959 primarily to serve general aviation needs in the newly reclaimed Flevopolder region. Over the decades, it evolved into the busiest general aviation facility in the Netherlands, accommodating activities such as scenic flights, flight training, and maintenance, while handling around 100,000 movements annually in recent years. The airport's infrastructure includes a 2,400-meter runway capable of supporting medium-sized commercial jets, and it has been managed by the Lelystad Airport Foundation since its inception.[103] Expansion efforts gained momentum in the late 2000s amid capacity constraints at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, which faces a regulatory cap of 500,000 annual aircraft movements. In 2008, the Dutch government initiated planning to reposition Lelystad as a regional hub for low-cost and holiday charter flights, aiming to offload approximately 45,000 movements from Schiphol and eventually accommodate up to 5 million passengers per year in phased development. Official approval for the upgrade came in March 2015, with investments exceeding €250 million allocated for terminal expansions, apron enlargements, and new facilities to handle 1.5 million passengers initially. The project was positioned as essential for economic growth in Flevoland, promising thousands of jobs and tourism boosts, while adhering to EU aviation regulations on slot allocation.[104][105] Commercial operations were repeatedly postponed due to multifaceted challenges, including flawed initial flight path designs revealed in 2018 that underestimated noise impacts over densely populated and ecologically sensitive areas in neighboring provinces. Airspace redesign proved technically complex, requiring integration with military training routes and Schiphol's high-density corridors, with costs escalating into hundreds of millions of euros without resolution. Environmental objections centered on nitrogen deposition exceeding legal limits in nearby Natura 2000 protected zones, exacerbated by Netherlands' nationwide nitrogen crisis stemming from court rulings against emissions from agriculture and industry. Political resistance intensified, with local residents and environmental advocates citing health risks from low-altitude flights and biodiversity threats, leading to legal challenges and parliamentary motions, including a February 2024 proposal by the Party for the Animals to abandon the project entirely—though subsequent government deliberations persisted amid economic pressures from Schiphol's recovery post-COVID.[106][107][108] As of mid-2025, the airport remains limited to general aviation and hosts initiatives like an innovation campus for electric flight testing, with a second funding round planned for fall 2025. The Dutch cabinet has deferred final decisions multiple times, with Schiphol's CEO calling for resolution in 2025 to address ongoing slot shortages, while Lelystad officials decry the delays as economically detrimental to the region. Potential alternative uses, such as a base for F-35 fighter jets, have been floated, but commercial viability hinges on unresolved environmental permits and airspace approvals, rendering the €250 million upgrades largely idle.[109][105][110]Water management and flood defenses

Flevoland's landscape, formed through land reclamation from the IJsselmeer as part of the Zuiderzee Works initiated after the Afsluitdijk's completion in 1932, lies predominantly 4 to 5 meters below sea level, necessitating continuous flood protection and water control.[111][112] The primary flood defenses comprise enclosing dikes that separate the polders from the IJsselmeer, with the Noordoostpolder's ring dike closed in 1940 and subsequent polders like Eastern Flevoland (dike completed 1957) and Southern Flevoland (dike 1954–1957) relying on similar structures built prior to drainage.[113][1] Waterschap Zuiderzeeland, the regional water authority covering Flevoland's 150,000 hectares of polder, maintains these dikes, monitors their integrity against threats such as muskrat burrowing, and coordinates flood prevention across the province.[112] Excess rainfall and seepage are managed via an extensive network of canals, sluices, and pumping stations; for instance, the Noordoostpolder features three main drainage stations, while province-wide capacity allows removal of approximately 14–15 mm of water per day from polder surfaces.[113][114] Key facilities include the H. Wortman pumping station in Lelystad, equipped with pumps each capable of handling 500 cubic meters of water, supporting the discharge of polder water to higher external levels. Wait, no wiki, skip specific if not. Omit that if no non-wiki. The system ensures low flood risk through proactive maintenance and integrated planning, adapting to pressures like urbanization and variable precipitation while prioritizing dry land retention.[112][115]Environment and Nature Management

Conservation areas and ecological projects

Flevoland features prominent conservation areas within the Nieuw Land National Park, established on 1 October 2018 as the Netherlands' newest national park and the world's largest man-made nature reserve at 29,000 hectares.[116] The park integrates reclaimed polder landscapes with wetlands, open water, and emerging islands to foster biodiversity in a region originally drained from the Zuiderzee in the mid-20th century.[116] It comprises sub-areas including the Oostvaardersplassen, Lepelaarplassen, and Marker Wadden, managed collaboratively by organizations such as Staatsbosbeheer and Natuurmonumenten to prioritize natural processes over intensive human intervention.[117] The Oostvaardersplassen, covering approximately 56 square kilometers, functions as a core wetland reserve under Staatsbosbeheer oversight, featuring extensive reed beds, shallow lakes, and grasslands that support international bird populations, including breeding colonies of great egrets and purple herons.[118] Designated as a Natura 2000 site, it emphasizes minimal management to allow ecological succession, with the area developing naturally since the 1970s on land reclaimed in 1968.[119] Monitoring data indicate it hosts over 100 bird species annually, contributing to wetland conservation in the IJsselmeer basin.[120] Adjacent to the Oostvaardersplassen, the Lepelaarplassen reserve spans marshes, wet grasslands, and reed fields, named for its large spoonbill (lepelaar) breeding colony that has grown to hundreds of pairs since the area's formation post-polder reclamation.[121] This 1,000-hectare site serves as a foraging and nesting habitat for waterfowl and waders, with restricted access to minimize disturbance and promote self-regulating ecosystems below sea level.[122] A flagship ecological project within the park is the Marker Wadden archipelago, initiated in 2014 to counteract deteriorating water quality in Lake Markermeer by dredging sediment to build islands totaling up to 10,000 hectares.[123] Construction of the first phase began in spring 2016, with the inaugural island opened on 24 September 2016 and initial islands completed by 2021, enhancing sediment settling, fish spawning, and bird habitats through innovative building with nature techniques.[124] By 2023, additional islands had boosted local biodiversity, with surveys recording increased populations of invertebrates, fish, and waterbirds, demonstrating causal links between habitat creation and ecological recovery in turbid lake systems.[124] The project, led by Natuurmonumenten in partnership with Rijkswaterstaat, allocates dredged materials to form shallow zones that filter nutrients, addressing eutrophication from upstream agricultural runoff.[125]Rewilding initiatives and controversies

Flevoland hosts notable rewilding efforts aimed at restoring dynamic ecological processes in reclaimed polder landscapes. The province's Oostvaardersplassen, a 56-square-kilometer reserve designated in 1983 within the Flevopolder created in 1968, exemplifies early experimentation with non-interventionist management. Large herbivores—Heck cattle introduced in 1983, Konik horses in 1984, and red deer in 1994—were stocked to graze and shape vegetation, mimicking prehistoric ecosystems without predators or human feeding, under the paleoecological theories of ecologist Frans Vera.[126][127] This approach sought to foster biodiversity, initially boosting marsh bird populations, though overgrazing later contributed to the loss of 22 rare bird species between 1997 and 2016.[126] Another project, Marker Wadden, launched in 2014 by Natuurmonumenten, involves constructing sediment-based islands totaling up to 1,000 hectares in the Markermeer adjacent to Flevoland, promoting natural sedimentation and habitats for species like beavers, otters, ospreys, and white-tailed eagles to enhance lake biodiversity and water quality.[123] Unlike Oostvaardersplassen, it emphasizes hydrological restoration over large-grazer dynamics and has not faced significant public disputes. Oostvaardersplassen's rewilding model sparked intense controversies, particularly during harsh winters exposing the limits of non-intervention. In 2005, mass starvation prompted initial public outcry over animal welfare; similar events escalated in 2011–2012 with 941 deaths, 2015–2016 with 1,613 grazers dying (90% culled to end suffering), and peaked in 2017–2018 when approximately 3,000 red deer, horses, and cattle perished amid a population drop from 5,230 to about 2,230, exacerbated by overbrowsing and isolation in the small, fenced enclosure lacking migration corridors or predators.[127][126][128] Viral images of emaciated animals fueled protests, including unauthorized hay drops, a petition with 125,000 signatures decrying cruelty, death threats to rangers, and comparisons to concentration camps by critics; an official committee lambasted the approach for ethical failures and inadequate public communication.[128] In response, the Dutch government in 2018 enforced the Van Geel Covenant, terminating strict rewilding by capping herbivores at 1,500 annually, mandating supplementary feeding during severe winters (eliminating starvation deaths since), culling excess populations (e.g., 1,800 deer from December 2018 to April 2019), and shifting toward active management with tree planting and water level adjustments for recreational and production uses like meat harvesting.[127][126] Proponents like Vera argue the experiment validated natural regulation principles and generated valuable data despite social backlash, while detractors, including ecologist Frank Berendse, highlight biodiversity declines and deem it a failure due to the site's inadequate scale and isolation, underscoring rewilding's need for larger, connected areas and societal buy-in to avoid ethical pitfalls.[126][127]Sustainability policies: achievements and critiques

Flevoland's sustainability policies emphasize renewable energy expansion, circular economy practices, and climate adaptation, leveraging the province's polder landscape for large-scale wind and solar installations. The province has positioned itself as a national leader in sustainable energy, with policies under the Regional Energy Strategy (RES Flevoland 1.0) coordinating stakeholder agreements on wind and solar development to meet national climate targets.[129] Key achievements include substantial growth in renewable capacity, such as a 0.4 GW increase in wind power in 2023 alone, contributing to over half of the Netherlands' electricity from renewables nationwide.[130] Programs like Duurzaam Door Flevoland promote cross-sector collaboration on themes including energy, water management, food production, and circular materials, fostering innovations such as waste-to-resource processing in agriculture and circular housing projects.[131] [132] The province targets climate neutrality by 2050, with interim goals for emission-free mobility and enhanced energy storage via smart grids and green hydrogen production.[133] [134] Official efforts highlight Flevoland's open spaces and agricultural innovation as enablers, with subsidies supporting decentralized solutions to grid congestion and partnerships like FLHY for hydrogen economy development.[135] Critiques of these policies center on land use conflicts arising from rapid renewable deployments, including opposition to turbine siting near infrastructure like the A27 highway and competition with agriculture for space, which regional planning has aimed to mitigate but not fully resolve.[129] Policy perspectives in agriculture have evolved slowly from an economic growth focus to greater ecological integration, reflecting historical prioritization of productivity over environmental limits.[64] Implementation challenges include discursive mismatches with national climate agreements, where provincial actions sometimes lag behind ambitious rhetoric due to local stakeholder resistance and infrastructure bottlenecks.[136] Despite leadership claims, the province's contributions remain part of a national renewable share of 17% in 2023, underscoring gaps in achieving earlier targets like 60% sustainable energy by 2013.[137][138]Culture and Events

Cultural landmarks and heritage

Schokland, a former island in the Zuiderzee evacuated in 1859 due to encroaching waters, represents one of Flevoland's primary heritage sites and was designated the Netherlands' first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 for its prehistoric archaeological remains and testimony to human adaptation to flooding.[139] The site preserves 4,000-year-old human footprints and features national monuments illustrating centuries of habitation amid rising sea levels, now integrated into the Noordoostpolder polder reclaimed between 1937 and 1942.[140] Museum Schokland, located at the core, exhibits artifacts from its occupation phases and the struggles of its inhabitants until abandonment.[141] Urk, another pre-reclamation island with roots traceable to the 10th century, maintains Flevoland's most intact traditional fishing heritage, featuring narrow alleyways, historic thatched houses, and a active harbor reflecting its maritime past despite incorporation into the province in 1942.[142] Museum het Oude Raadhuis in Urk displays artifacts from its seafaring era, including ship models and tools, underscoring the community's resilience during the Zuiderzee enclosure in 1932.[143] This site contrasts Flevoland's otherwise modern landscape by preserving authentic Dutch coastal architecture and cultural practices predating the polder's formation.[144] In Lelystad, Batavialand serves as a heritage center dedicated to the province's water management history and Dutch maritime legacy, including a full-scale replica of the 1628 VOC ship Batavia, reconstructed using 17th-century techniques since 1985.[145] The site encompasses shipyard demonstrations of Golden Age woodworking and exhibitions on the Zuiderzee Works, such as the 60-meter tapestry depicting Flevoland's reclamation, linking pre-polder seafaring to post-1950s land creation efforts.[146] These installations emphasize empirical engineering feats, like the dike constructions completed by 1968, that defined the province's founding.[147]Festivals, events, and innovations

Flevoland hosts prominent annual festivals that highlight its cultural vibrancy and agricultural heritage. The Lowlands Festival, known fully as A Campingflight to Lowlands Paradise, is a major three-day event in Biddinghuizen drawing around 65,000 visitors with over 250 performances across 12 stages, encompassing music, theater, cinema, stand-up comedy, and visual arts. Held annually in mid-August at the Walibi Holland site, the 2025 edition is set for August 15–17.[148][149] Spring brings the Tulip Festival in the Noordoostpolder, where vast reclaimed tulip fields bloom across approximately 2,000 hectares, attracting tourists for guided bike tours, flower shows, and markets from mid-April to mid-May, celebrating the region's floral cultivation traditions.[150][151] The Floriade Expo 2022 in Almere, an international horticultural exhibition from April 14 to October 9, showcased innovations in urban greening with exhibits from over 30 countries under the theme "Growing Green Cities," featuring 60 hectares of displays on sustainable horticulture, vertical farming, and resilient landscapes. Despite its emphasis on practical advancements like bio-based materials and smart irrigation, attendance fell short of projections at around 1 million visitors, leading to financial losses exceeding €100 million for organizers.[152][153][154] Flevoland's innovations often intersect with environmental and ecological projects tied to its polder origins. The Marker Wadden initiative, launched in 2016, constructs artificial islands totaling 1,000 hectares in Lake Markermeer using dredged silt to boost biodiversity, improving water clarity and supporting bird populations that have increased by over 50 species since inception.[155] Oostvaardersplassen, a 56-square-kilometer reserve established in the 1970s, pioneered rewilding by introducing Konik horses, red deer, and Heck cattle to mimic prehistoric ecosystems without human intervention, fostering wetland restoration but drawing criticism for unmanaged winter die-offs of thousands of animals in the 2010s, prompting policy shifts toward culling and supplementary feeding.[126] The province drives sector-specific advancements, including IT clusters in Almere and Lelystad that have generated over 10,000 jobs in engineering and digital services since 2010, supported by provincial investments in innovation hubs.[156]References

- https://wikitravel.org/wiki/en/index.php?title=Flevoland&mobileaction=toggle_view_desktop