Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Gilgit River.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gilgit River

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Gilgit River | |

|---|---|

| |

Course of the Gilgit River | |

| Native name | دریائے گلگت (Urdu) |

| Location | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Autonomous territory | Gilgit-Baltistan |

| Districts | Gupis-Yasin, Ghizer and Gilgit |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mouth | |

• coordinates | 35°44′31″N 74°37′29″E / 35.74194°N 74.62472°E |

| Length | 240 km |

| Basin features | |

| Waterbodies | Shandur Lake, Phander Lake, Attabad Lake |

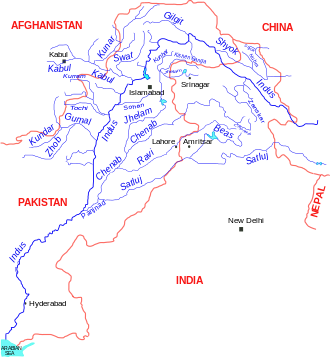

The Gilgit River (Urdu: دریائے گلگت) is a tributary of the Indus River, flowing through various districts of Pakistan's Gilgit-Baltistan region, including Gupis-Yasin, Ghizer and Gilgit. The Gilgit River originates from Shandur Lake[1] and proceeds to join the Indus River near the towns of Juglot and Bunji. This confluence is believed to mark the meeting point of three prominent mountain ranges: the Hindu Kush, the Himalayas, and the Karakoram.[2][3]

The upper sections of the Gilgit River are referred to as the Gupis River and Ghizer River.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ isbn:1483603792 - Cerca con Google (in Italian).

- ^ Handy, Norman (2017). K2, The Savage Mountain: Travels in Northern Pakistan. novum pro Verlag. ISBN 9783990487174.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gilgit River.

Gilgit River

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia