Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dirofilaria immitis

View on Wikipedia

| Dirofilaria immitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| A German Shepherd dog heart infested with Dirofilaria immitis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Rhabditida |

| Family: | Onchocercidae |

| Genus: | Dirofilaria |

| Species: | D. immitis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy, 1856)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Filaria immitis Leidy, 1856 | |

Dirofilaria immitis, also known as heartworm or dog heartworm, is a parasitic roundworm that is a type of filarial worm, a small thread-like worm, and which causes dirofilariasis. It is spread from host to host through the bites of mosquitoes. Four genera of mosquitoes transmit dirofilariasis, Aedes, Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia.[2] The definitive host is the dog, but it can also infect cats, wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes, ferrets, bears, seals, sea lions and, under rare circumstances, humans.[3]

Adult heartworms often reside in the pulmonary arterial system (lung arteries) as well as the heart, and a major health effect in the infected animal host is damage to its lung vessels and tissues.[4] In cases involving advanced worm infestation, adult heartworms may migrate to the right heart and the pulmonary artery. Heartworm infection may result in serious complications for the infected host if left untreated, eventually leading to death, most often as a result of secondary congestive heart failure.

Distribution and epidemiology

[edit]Although at one time confined to the southern United States, heartworm has now spread to nearly all locations where its mosquito vector is found. In the southeast region of the United States, veterinary clinics saw an average of more than 100 cases of heartworm each in 2016.[5] Transmission of the parasite occurs in all of the United States (cases have even been reported in Alaska), and the warmer regions of Canada. The highest infection rates are found within 150 miles (240 km) of the coast from Texas to New Jersey, and along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries.[4] It has also been found in South America,[6] southern Europe,[7][8] Southeast Asia,[9] the Middle East,[10] Australia, Korea, and Japan.[11][12]

Course of infection

[edit]

Heartworms go through several life stages before they become adults infecting the pulmonary artery of the host animal. The worms require the mosquito as an intermediate host to complete their lifecycles. The rate of development in the mosquito is temperature-dependent, requiring about two weeks of temperature at or above 27 °C (80 °F). Below a threshold temperature of 14 °C (57 °F), development cannot occur, and the cycle is halted.[13] As a result, transmission is limited to warm weather, and duration of the transmission season varies geographically. The period between the initial infection when the dog is bitten by a mosquito and the maturation of the worms into adults living in the pulmonary arteries takes six to seven months in dogs and is known as the "prepatent period".[14]

The first larval stage (L1) and second larval stage (L2) of heartworm development occurs within the body of a mosquito. Once the larvae develop into the infective third larval stage (L3), the mosquito locates and bites a host, depositing the larvae under the skin at the site of the bite. After a week or two of further growth, they molt into the fourth larval stage (L4) . Then, they migrate to the muscles of the chest and abdomen, and 45 to 60 days after infection, molt to the fifth stage (L5, immature adult). Between 75 and 120 days after infection, these immature heartworms then enter the bloodstream and are carried through the heart to reside in the pulmonary artery. Over the next three to four months, they increase greatly in size. The female adult worm is about 30 cm in length, and the male is about 23 cm, with a coiled tail.[15] By seven months after infection, the adult worms have mated and the females begin giving birth to live young, called microfilariae. Heartworms can live for 5 to 7 years in a dog.[16]

The microfilariae circulate in the bloodstream for as long as two years, and are ingested by bloodsucking mosquitos, where development occurs and the cycle repeats.[citation needed]

Hosts

[edit]Hosts of Dirofilaria immitis include:[3]

Reservoir hosts for D. immitis are coyotes and stray dogs.[19]

Clinical signs of infection in dogs

[edit]Dogs show no indication of heartworm infection during the six-month prepatent period prior to the worms' maturation, and current diagnostic tests for the presence of microfilariae or antigens cannot detect prepatent infections. Rarely, migrating heartworm larvae get "lost" and end up in aberrant sites, such as the eye, brain, or an artery in the leg, which results in unusual symptoms such as blindness, seizures, and lameness, but normally, until the larvae mature and congregate inside the heart, they produce no symptoms or signs of illness.[20]

Many dogs show little or no sign of infection even after the worms become adults. These animals usually have only a light infection and live a fairly sedentary lifestyle. However, active dogs and those with heavier infections may show the classic signs of heartworm disease. Early signs include a cough, especially during or after exercise, and exercise intolerance. In the most advanced cases where many adult worms have built up in the heart without treatment, signs progress to severe weight loss, fainting, coughing up blood, and finally, congestive heart failure.[citation needed]

There are four different classes of symptoms:

- Class 1 – no or mild symptoms with occasional cough.

- Class 2 – mild symptoms with occasional cough and tiredness after moderate activity.

- Class 3 – more severe symptoms, including a generally sick appearance, persistent cough, difficulty breathing, and tiredness after mild activity. Heart and lung changes may be seen with a chest x-ray.

- Class 4 – also called caval syndrome. The blood flowing back to the heart is blocked due to the large mass of worms. This is life-threatening and the only treatment option is surgery.[21]

Role of Wolbachia pipientis

[edit]Wolbachia pipientis is an intracellular bacterium that is an endosymbiont of D. immitis. All heartworms are thought to be infected with Wolbachia to some degree. The inflammation occurring at the die-off of adult heartworms or larvae is in part due to the release of Wolbachia bacteria or protein into the tissues. This may be particularly significant in cats, in which the disease seems to be more related to larval death than living adult heartworms. Treating heartworm-positive animals with an antibiotic such as doxycycline to remove Wolbachia may prove to be beneficial as it does for the filariae that cause elephantiasis,[22] but further studies are necessary.[23]

Diagnosis in dogs

[edit]

Microfilarial detection is accomplished by the using one of the following methods:

Direct blood smear

[edit]A blood sample is collected and viewed under the microscope. The direct smear technique allows examination of larval motion, confirming the presence of microfilaria. It also helps in the distinction of D. immitis from Acanthocheilonema reconditum. This distinction is important because the presence of the latter parasite does not pose a health risk to the host. D. immitis usually has stationary body movement, while A. reconditum has progressive movement. However, this method often misses light infections because only a small amount of blood sample is used.[25]

Hematocrit tube method

[edit]This method uses a microhematocrit (or capillary tube) filled with a blood sample that has been centrifuged, separating the plasma from the red blood cells. These layers are divided by the buffy coat. The buffy coat consists of the leukocytes and platelets that are in the sample. The tube is snapped at the buffy coat and added to a slide for microscopic examination. Adding methylene blue stain to the sample may allow greater visibility of any microfilariae. However, the hematocrit tube method will not allow for species differentiation.[26]

Modified Knott's test

[edit]The modified Knott's test is more sensitive because it concentrates microfilariae, improving the chance of diagnosis.[4] A blood sample is mixed with 2% formalin and centrifuged in a tube. The supernatant is removed and methylene blue stain is added to the pellet remaining in the tube for microscopic examination. It allows microfilariae species differentiation based on morphology. Microfilariae can be differentiated between D. immitis and Acanthocheilonema reconditum because of small differences in morphology. The Modified Knott's test is the best method of visual examination when determining presence of microfilaria because it preserves their morphology and size. It is easy to perform, quick, and inexpensive.[27]

The potential for a microfilaremic infection is 5 – 67%. The number of circulating microfilariae does not correlate with the number of adult heartworms, so is not an indicator of disease severity.[4]

Antigen testing

[edit]In most practices, antigen testing has supplanted or supplemented microfilarial detection.[citation needed] Combining the microfilaria and adult antigen test is most useful in dogs receiving diethylcarbamazine or no preventive (macrolides like ivermectin or moxidectin typically render the dog amicrofilaremic). Up to 1% of infected dogs are microfilaria-positive and antigen-negative.[4] Immunodiagnostics (ELISA, lateral flow immunoassay, rapid immunomigration techniques) to detect heartworm antigen in the host's blood are now regularly used. They can detect occult infections, or infections without the presence of circulating microfilariae. However, these tests are limited in that they only detect the antigens released from the sexually mature female worm's reproductive tract. Therefore, false-negative results may occur during the first five to eight months of infection when the worms are not yet sexually mature.[4] The specificity of these tests is close to 100%, and the sensitivity is more than 80%.[28] A recent study demonstrated a sensitivity of only 64% for infections of only one female worm, but improved with increasing female worm burden (85%, 88%, and 89% for two, three, and four female worms, respectively). Specificity in this study was 97%.[4] False-negative test results can be due to low worm counts, immature infections, and all-male infections.

X-rays

[edit]X-rays are used to evaluate the severity of the heartworm infection and develop a prognosis for the animal. Typically, the changes observed are enlargement of the main pulmonary artery, the right side of the heart, and the pulmonary arteries in the lobes of the lung. Inflammation of the lung tissue is also often observed.[29]

Treatment in dogs

[edit]If an animal is diagnosed with heartworms, treatment may be indicated. Before the worms can be treated, however, the dog's heart, liver, and kidney function must be evaluated to determine the risks of treatment. Usually, the adult worms are killed with an arsenic-based compound. The currently approved drug in the US, melarsomine, is marketed under the brand name Immiticide.[30] It has a greater efficacy and fewer side effects than the previously used drug thiacetarsamide, sold as Caparsolate, which makes it a safer alternative for dogs with late-stage infections.[citation needed]

After treatment, the dog must rest, and exercise is to be heavily reduced for several weeks so as to give its body sufficient time to absorb the dead worms without ill effect. Otherwise, if the dog is under exertion, dead worms may break loose and travel to the lungs, potentially causing respiratory failure and sudden death. According to the American Heartworm Society, the administering of aspirin to dogs infected with heartworms is no longer recommended due to a lack of evidence of clinical benefit, and aspirin may be contraindicated in several cases. Aspirin had previously been recommended for its effects on platelet adhesion and the reduction of vascular damage caused by the heartworms.[citation needed]

The course of treatment is not completed until several weeks later, when the microfilariae are dealt with in a separate course of treatment. Once heartworm tests are negative and no surviving worm is detected, the treatment is considered a success, and the patient is effectively cured.[citation needed]

Surgical removal of the adult heartworms as a form of treatment may also be indicated, especially in advanced cases with substantial heart involvement and damage.[31]

Prevention of infection in dogs

[edit]Prevention of heartworm infection can be obtained through a number of veterinary drugs. The drugs approved for use in the US are ivermectin (sold under the brand names Heartgard, Iverhart, and several other generic versions), milbemycin (Interceptor Flavor Tabs and Sentinel Flavor Tabs) and moxidectin (Simparica Trio) administered as chewable tablets. Moxidectin is also available in both a six-month and 12-month sustained-release injection, ProHeart 6 and ProHeart 12, respectively, administered by veterinarians. This injectable form of moxidectin was taken off the market in the United States due to safety concerns in 2004, but the FDA returned a newly formulated ProHeart 6 to the market in 2008. ProHeart 6 remains on the market in many other countries, including Canada and Japan. Its sister product, ProHeart 12, is used extensively in Australia and Asia as a 12-month injectable preventive. It was approved for use in the United States by the FDA in July 2019.[32] Topical treatments are available, as well. Advantage Multi (imidacloprid plus moxidectin) Topical Solution, uses moxidectin for control and prevention of roundworms, hookworms, heartworms, and whipworms, as well as imidacloprid to kill adult fleas. Selamectin (Revolution) is a topical preventive likewise administered monthly, and can also be used to control fleas, ticks, and mites.[citation needed]

Preventive drugs are highly effective, and when regularly administered, have been shown to protect more than 99% of dogs and cats from heartworm. Most compromises in protection result from the failure to properly administer the drugs during seasonal transmission periods.[33] In regions where the temperature is consistently above 14 °C (57 °F) year-round, a continuous prevention schedule is recommended.[citation needed]

Due to newly emerging resistant strains of heartworms, which no macrocyclic lactone (heartworm prevention) can protect against, the American Heartworm Society recommends dogs be on a repellent and a heartworm preventive. The repellent, such as Vectra 3-D, keeps mosquitoes from feeding on the dog and transmitting the L3 stage worms. If a dog is bitten, the heartworm preventive takes over when administered. If a mosquito feeds on a heartworm positive dog on a repellent, they do not live long enough for the microfilaria they ingested to molt into the infective L3 larva. Vectra 3-D was tested using thousands of mosquitoes infected with the resistant heartworm strain JYD34. In the control group that was given only a placebo, every dog contracted heartworms. In the experimental group that was given only Vectra 3-D, two of eight dogs contracted heartworms and had an average of 1.5 adult worms each. In the experimental group given both heartworm prevention and Vectra 3-D, one dog was infected with L3 stage larvae that did not mature into adulthood due to the heartworm prevention. Using a repellent and a prevention is at least 95% effective.[34][35]

Ivermectin, even with lapses up to four months between doses, still provides 95% protection from adult worms. This period is called the reach-back effect.[36] Since dogs are susceptible to heartworms, they should be tested annually before they start preventive treatment.[19] Annual heartworm testing is highly recommended for pet owners who choose to use minimal dosing schedules. Testing a dog annually for heartworms and other internal parasites is a fundamental part of a complete heartworm prevention program, and is also recommended for dogs who are already on a monthly prevention program.[19]

Heartworm infection in cats

[edit]While dogs are a natural host for D. immitis, cats are atypical hosts. Because of this, differences between canine and feline heartworm diseases are significant. The majority of heartworm larvae do not survive in cats, so unlike in dogs, a typical infection in cats is two to five worms. The lifespan of heartworms is considerably shorter in cats, only two to three years, and most infections in cats do not have circulating microfilariae. Cats are also more likely to have aberrant migration of heartworm larvae, resulting in infections in the brain or body cavities.[37]

The infection rate in cats is 1–5% of that in dogs in endemic areas.[38] Both indoor and outdoor cats are infected. The mosquito vector is known to enter homes.[39]

Pathology

[edit]The vascular disease in cats that occurs when the L5 larvae invade the pulmonary arteries is more severe than in dogs. A reaction has been identified in cats: heartworm-associated respiratory disease, which can occur three to four months after the initial infection, and is caused by the presence of the L5 larvae in the vessels. The subsequent inflammation of the pulmonary vasculature and lungs can be easily misdiagnosed as feline asthma or allergic bronchitis.[40]

Obstruction of pulmonary arteries due to emboli from dying worms is more likely to be fatal in cats than dogs because of less collateral circulation and fewer vessels.[41] Heartworms can live for 2 to 3 years in cats.[16]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Acute heartworm disease in cats can result in shock, vomiting, diarrhea, fainting, and sudden death. Chronic infection can cause loss of appetite, weight loss, lethargy, exercise intolerance, coughing, and difficulty breathing. Some cats' immune systems are able to clear a heartworm infection, though the immune system response can cause many of the same symptoms. Also, even if the infection resolves, respiratory damage can cause some symptoms to persist beyond it.[40][need quotation to verify][42]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of heartworm infection in cats is problematic. Like in dogs, a positive ELISA test for heartworm antigen is a very strong indication of infection. However, the likelihood of a positive antigen test depends on the number of adult female worms present. If only male worms are present, the test will be negative. Even with female worms, an antigen test usually only becomes positive seven to eight months after infection. Therefore, a cat may have significant clinical signs long before the development of a positive test. Heartworm-associated respiratory disease can be found in cats that never develop adult heartworms and therefore never have a positive antigen test.[citation needed]

An antibody test is also available for feline heartworm infection. It will be positive in the event of exposure to D. immitis, so a cat that has successfully eliminated an infection may still be positive for up to three months. The antibody test is more sensitive than the antigen test, but it does not provide direct evidence of adult infection.[43] It can, however, be considered specific for diagnosing previous larval infections, and therefore fairly specific for heartworm-associated respiratory disease.

X-rays of the chest of a heartworm-infected cat may show an increased width of the pulmonary arteries and focal or diffuse opacities in the lungs. Echocardiography is a fairly sensitive test in cats. Adult heartworms appear as double-lined hyperechoic structures within the heart or pulmonary arteries.[44]

Treatment and prevention

[edit]

Heartworm prevention for cats is available as ivermectin (Heartgard for Cats), milbemycin (Interceptor), or the topical selamectin (Revolution for Cats) and Advantage Multi (imidacloprid + moxidectin) topical solution. Ivermectin, milbemycin, and selamectin are approved for use in cats in the US.[citation needed]

Arsenic compounds have been used for heartworm adulticide treatment in cats, as well as dogs, but seem more likely to cause pulmonary reactions. A significant number of cats develop pulmonary embolisms a few days after treatment. The effects of melarsomine are poorly studied in cats. Due to a lack of studies showing a clear benefit of treatment and the short lifespan of heartworms in cats, adulticide therapy is not recommended, and no drugs are approved in the US for this purpose in cats.[41]

Treatment typically consists of putting the cat on a monthly heartworm preventive and a short-term corticosteroid.[37] Surgery has also been used successfully to remove adult worms. The prognosis for feline heartworm disease is guarded.[45][clarification needed][citation needed]

Heartworm infection in humans

[edit]Dirofilaria are important medical parasites, but diagnosis is unusual and is often only made after an infected person happens to have a chest X-ray following granuloma formation in the lung. The nodule itself may be large enough to resemble lung cancer on the X-ray, and requires a biopsy for a pathologic assessment.[18] This has been shown to be the most significant medical consequence of human infection by the canine heartworm. Patients are infected with the parasite through the bite of an infected mosquito, which is the same mechanism that causes heartworm infection in dogs.[46][medical citation needed]

D. immitis is one of many species that can cause infection in dogs and humans. It was thought to infect the human eye,[18] with most cases reported from the southeastern United States. However, these cases are now thought to be caused by a closely related parasite of raccoons, Dirofilaria tenuis. Several hundred cases of subcutaneous infections in humans have been reported in Europe, but these are almost always caused by another closely related parasite, Dirofilaria repens, rather than the dog heartworm. There are proven D. immitis infections,[18] but humans rarely get infected with heartworms due to the larvae never fully maturing.[medical citation needed] When the heartworm infective larvae migrate through the skin, they often die since heartworms cannot survive in a human host, even if they make it into the bloodstream. Once the heartworms die, the immune system in the human body reacts to their tissue with inflammation as it tries to destroy the heartworms.[medical citation needed] When this happens, the condition is called pulmonary dirofilariasis. Heartworm infection in humans is not a serious problem unless they are causing pain, discomfort, and other noticeable symptoms.[medical citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy, 1856)". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Global Health, Division of Parasitic Diseases (2012-02-08). "CDC – Dirofliariasis – Biology – Life Cycle of D. immitis". www.cdc.gov. CDC-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 2019-06-15.

- ^ a b "American Heartworm Society | FAQs". Heartwormsociety.org. Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (2010). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (7th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-1-4160-6593-7.

- ^ Heartworm Incidence Maps. American Heartworm Society. 1970 Apr 10 [cited 2019 Apr 16]. https://www.heartwormsociety.org/pet-owner-resources/incidence-maps Archived 2019-04-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Vezzani D, Carbajo A (2006). "Spatial and temporal transmission risk of Dirofilaria immitis in Argentina". Int J Parasitol. 36 (14): 1463–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.08.012. PMID 17027990.

- ^ "Heartworm Disease: Introduction". The Merck Veterinary Manual /. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Vieira, Ana Luísa; Vieira, Maria João; Oliveira, João Manuel; Simões, Ana Rita; Diez-Baños, Pablo; Gestal, Juan (2014). "Prevalence of canine heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) disease in dogs of central Portugal". Parasite. 21: 5. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014003. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 3927308. PMID 24534524.

- ^ Nithiuthai, Suwannee (2003). "Risk of Canine Heartworm Infection in Thailand". Proceedings of the 28th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Rafiee, Mashhady (2005). "Study of Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis Infestation in Dogs were Examined in Veterinary Clinics of Tabriz Azad University (Iran) during 1992–2002". Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6795-9.

- ^ Oi, M.; Yoshikawa, S.; Ichikawa, Y.; Nakagaki, K.; Matsumoto, J.; Nogami, S. (2014). "Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis among shelter dogs in Tokyo, Japan, after a decade: comparison of 1999–2001 and 2009–2011". Parasite. 21: 10. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014008. PMC 3937804. PMID 24581552.

- ^ Knight, D. H.; Lok, J. B. (May 1998). "Seasonality of heartworm infection and implications for chemoprophylaxis". Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice. 13 (2): 77–82. doi:10.1016/S1096-2867(98)80010-8. ISSN 1096-2867. PMID 9753795.

- ^ Bowman, Dwight (2021). Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians (Eleventh ed.). W. B. Saunders. p. 135-260. ISBN 978-0-323-54396-5.

- ^ Johnstone, Colin (1998). "Heartworm". Parasites and Parasitic Diseases of Domestic Animals. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2000-12-06. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ a b "Heartworm Basics – American Heartworm Society". www.heartwormsociety.org. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- ^ Mazzariol, S.; Cassini, R.; Voltan, L.; Aresu, L.; di Regalbono, A. F. (2010). "Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in a leopard (Panthera pardus pardus) housed in a zoological park in north-eastern Italy". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-25. PMC 2858128. PMID 20377859.

- ^ a b c d Tumolskaya, Nelli Ignatievna; Pozio, Edoardo; Rakova, Vera Mikhaylovna; Supriaga, Valentina Georgievna; Sergiev, Vladimir Petrovich; Morozov, Evgeny Nikolaevich; Morozova, Lola Farmonovna; Rezza, Giovanni; Litvinov, Serguei Kirillovich (2016). "Dirofilaria immitis in a child from the Russian Federation". Parasite. 23: 37. doi:10.1051/parasite/2016037. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5018928. PMID 27600944.

- ^ a b c Paul, Mike. 10 Things You Need to Know About Heartworm and Your Dog. Pet Health Network, 10 Sept. 2015 [cited 3 Apr 2019]. www.pethealthnetwork.com/dog-health/dog-diseases-conditions-a-z/10-things-you-need-know-about-heartworm-and-your-dog.

- ^ "Dirofilaria immitis - Learn About Parasites - Western College of Veterinary Medicine". wcvm-learnaboutparasites. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ Center for Veterinary Medicine (2022-12-22). "Keep the Worms Out of Your Pet's Heart! The Facts about Heartworm Disease". U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ Hoerauf A, Mand S, Fischer K, Kruppa T, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Debrah AY, et al. (November 2003). "Doxycycline as a novel strategy against bancroftian filariasis-depletion of Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancrofti and stop of microfilaria production". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 192 (4): 211–216. doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0174-6. PMID 12684759. S2CID 23349595.

- ^ Todd-Jenkins, Karen (October 2007). "The Role of Wolbachia in heartworm disease". Veterinary Forum. 24 (10): 28–30.

- ^ Wheeler, Lance. "Photostream". Flickr. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Sirois, M. (2015) Laboratory Procedures for Veterinary Technicians. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

- ^ "Diagnosis of Internal Parasites". Today's Veterinary Practice. 2013-07-01. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Magnis, Johannes; Lorentz, Susanne; Guardone, Lisa; Grimm, Felix; Magi, Marta; Naucke, Torsten J.; Deplazes, Peter (2013-02-25). "Morphometric analyses of canine blood microfilariae isolated by the Knott's test enables Dirofilaria immitis and D. repens species-specific and Acanthocheilonema (syn. Dipetalonema) genus-specific diagnosis". Parasites & Vectors. 6 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-6-48. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 3598535. PMID 23442771.

- ^ Atkins, Clarke (2005). "Heartworm Disease in Dogs: An Update". Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ "American Heaartworm Society". Archived from the original on 2013-11-04.

- ^ "Product Information". Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ "2005 Guidelines For the Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Dogs". American Heartworm Society. 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Medicine, Center for Veterinary (2019-07-02). "FDA Approves ProHeart 12 (moxidectin) for Prevention of Heartworm Disease in Dogs". FDA. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019.

- ^ Knight, David (1998-05-01). "Heartworm". Seasonality of Heartworm Infection and Implications for Chemoprophylaxis. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine.

- ^ "Fight Heartworm Now". Fight Heartworm Now. Archived from the original on 2018-08-18. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ "Yes, there's a new way to protect dogs from heartworm". Goodnewsforpets. 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ Atwell, R. (1988). "Heartworm". Dirofilariasis (CRC Press, 1988:30–34). Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ a b "2007 Guidelines For the Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Cats". American Heartworm Society. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ Berdoulay P, Levy JK, Snyder PS, et al. (2004). "Comparison of serological tests for the detection of natural heartworm infection in cats". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 40 (5): 376–84. doi:10.5326/0400376. PMID 15347617.

- ^ Atkins CE, DeFrancesco TC, Coats JR, Sidley JA, Keene BW (2000). "Heartworm infection in cats: 50 cases (1985–1997)". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 217 (3): 355–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.204.2733. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.217.355. PMID 10935039.

- ^ a b Yin, Sophia (June 2007). "Update on heartworm infection". Veterinary Forum. 24 (6): 42–43.

- ^ a b Atkins, Clarke E.; Litster, Annette L. (2005). "Heartworm Disease". In August, John R. (ed.). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0423-7.

- ^ Reno LVT, Tabitha (2017-05-05). "The Myths and Facts of Heartworm Disease in Cats". WhitesburgAnimalHospital.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ Atkins C (1999). "The diagnosis of feline heartworm infection". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 35 (3): 185–7. doi:10.5326/15473317-35-3-185. PMID 10333254.

- ^ DeFrancesco TC, Atkins CE, Miller MW, Meurs KM, Keene BW (2001). "Use of echocardiography for the diagnosis of heartworm disease in cats: 43 cases (1985–1997)". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218 (1): 66–9. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.218.66. PMID 11149717.

- ^ Garrity, Sarah; Lee-Fowler, Tekla; Reinero, Carol (September 2019). "Feline asthma and heartworm disease: Clinical features, diagnostics and therapeutics". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 21 (9): 825–834. doi:10.1177/1098612X18823348. ISSN 1532-2750. PMC 10814146. PMID 31446863.

- ^ "Heartworm Basics". American Heartworm Society. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Traversa, D.; Di Cesare, A.; Conboy, G. (2010). "Canine and feline cardiopulmonary parasitic nematodes in Europe: emerging and underestimated". Parasites & Vectors. 3: 62. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-62. PMC 2923136. PMID 20653938.

External links

[edit]- American Heartworm Society Founded in 1974, the American Heartworm Society is internationally recognized as the definitive authority with respect to heartworm disease in dogs and cats.

- Preventing Heartworm Infection in Dogs (VeterinaryPartner.com)

- Overview and main concepts of Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm) infection (MetaPathogen.com)

- Mosquito-borne Dog Heartworm Disease (University of Florida Extension Bulletin)

- Case Study of Canine Heartworm Disease (from the University of California, Davis)

- Case Study of Feline Heartworm Disease (from the University of California, Davis)

- Case Study of Canine Heartworm Disease (from the University of California, Davis)

Dirofilaria immitis

View on GrokipediaOverview and Taxonomy

Morphology and Biology

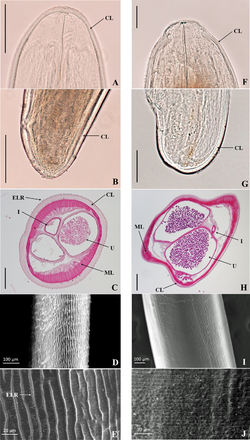

Dirofilaria immitis is a filarial nematode characterized by its elongated, thread-like body. Adult worms are slender and cylindrical, with females typically measuring 230–310 mm in length and approximately 0.35 mm in width, while males are smaller at 120–190 mm long and 0.3 mm wide. These dimensions contribute to their adaptation as vascular parasites, allowing them to reside within the host's circulatory system without causing immediate obstruction in low-burden infections.[1] As an endoparasite, D. immitis primarily inhabits the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle of the heart in its definitive hosts. The worms' smooth cuticle and muscular esophagus facilitate their movement and nutrient absorption in this vascular environment. Adults exhibit sexual dimorphism, with males possessing a coiled posterior end and copulatory bursa for mating, while females have a straight body terminating in a vulva near the anterior end.[1][11] The species is dioecious, requiring both male and female worms for reproduction, and viviparous, with gravid females producing live microfilariae directly into the host's bloodstream. A single female can release millions of microfilariae over her reproductive lifespan, though production begins approximately 6–9 months after infection and varies with worm burden and host factors. These microfilariae are the first-stage larvae (L1), measuring 300–322 μm in length and 6–7 μm in width, and are notable for being sheathless—a key morphological trait distinguishing them from sheathed microfilariae of other filariae. Their tail is bluntly rounded, with body nuclei extending continuously to the tip, providing a diagnostic feature under microscopic examination.[1][12][13][14] In untreated hosts, adult D. immitis worms have a lifespan of 5–10 years, during which they continue to reproduce and potentially increase in number through ongoing transmission. This longevity underscores the chronic nature of infection and the importance of preventive measures in endemic areas.[1]Classification and Etymology

Dirofilaria immitis belongs to the kingdom Animalia, phylum Nematoda, class Chromadorea, order Rhabditida, superfamily Filarioidea, family Onchocercidae, genus Dirofilaria, and species immitis.[15] This taxonomic placement situates it among the parasitic nematodes known as filarial worms, which are characterized by their elongated, thread-like bodies and dependence on arthropod vectors for transmission.[2] The genus name Dirofilaria derives from the Latin dīrus (meaning "fearful" or "ominous") combined with fīlum (meaning "thread"), reflecting the ominous nature of these thread-like parasites.[16] The species epithet immitis is Latin for "fierce" or "severe," alluding to the parasite's pathogenic impact on hosts. D. immitis was first described as a distinct species in 1856 by Joseph Leidy, based on specimens from canine hearts, marking its formal recognition within the filarial nematodes.[17] Prior to this, filarial parasites in dogs had been noted in historical records dating back to the 17th century, but Leidy's work established its specific identity.[11] Phylogenetically, D. immitis occupies a position within the Onchocercidae family, closely related to other filarial nematodes transmitted by arthropods, such as those in the genus Onchocerca.[7] It shares evolutionary ties with species like D. repens, which causes subcutaneous infections in canids and occasionally humans, differing primarily in tissue tropism—pulmonary for D. immitis versus dermal for D. repens.[11] Similarly, it is allied with Onchocerca volvulus, the causative agent of human onchocerciasis (river blindness), highlighting the family's pattern of vector-borne filariasis across vertebrate hosts.[18]Life Cycle and Transmission

Developmental Stages

The life cycle of Dirofilaria immitis involves distinct developmental stages progressing from microfilariae to adult worms, requiring both an arthropod vector and a mammalian host for completion. The first stage consists of microfilariae, which are the L1 larvae circulating in the bloodstream of the infected definitive host. These elongated, sheathed larvae measure approximately 250–300 μm in length and are produced by gravid female adults.[19] Upon ingestion by a suitable mosquito vector during a blood meal, the L1 microfilariae penetrate the mosquito's midgut wall and begin development. Within the midgut, they undergo the first molt to the L2 stage, often appearing as "sausage-shaped" forms, typically within 2–3 days under optimal conditions. The L2 larvae then migrate to the Malpighian tubules, where they complete a second molt to become L3 infective larvae after an additional 7–10 days. This extrinsic development phase in the vector requires 10–14 days at a mean ambient temperature exceeding 27°C (81°F) and relative humidity around 80%, with a minimum threshold of 57°F (14°C) for larval progression; below this temperature, development halts. The L3 larvae, measuring about 1,000 μm by 40 μm, migrate to the mosquito's proboscis and remain infective for up to 4 weeks.[19] When the infected mosquito takes another blood meal, the L3 larvae are deposited onto the skin of the mammalian host and actively penetrate the bite wound. In the host's subcutaneous tissues, the L3 undergo a third molt to the L4 stage within 3–4 days, accompanied by exsheathment of the L3 cuticle. The L4 larvae, now larger and more robust, migrate through connective tissues and reach the pulmonary arteries, where they molt a fourth time to the L5 juvenile adult stage around 50 days post-infection. These young adults continue maturing into sexually mature worms over the next 3–4 months, with females beginning to produce microfilariae after a prepatent period of 6–7 months from initial L3 inoculation. Molting in the mammalian host occurs in subcutaneous and pulmonary tissues, driven by internal physiological cues rather than specific environmental factors.[19][20][21]Vectors and Transmission Dynamics

_Dirofilaria immitis is transmitted exclusively by mosquitoes, with over 70 species across genera such as Aedes, Culex, Anopheles, Ochlerotatus, Coquillettidia, and Mansonia serving as competent vectors worldwide.[22] In the United States, at least 28 mosquito species are known to transmit the parasite, including Aedes taeniorhynchus, which acts as a primary vector in coastal regions like Yucatan, Mexico, and parts of Florida due to its abundance and high vector competence.[23][24] Transmission begins when a female mosquito ingests microfilariae (L1 larvae) of D. immitis during a blood meal from an infected host.[5] Within the mosquito, the microfilariae penetrate the midgut, migrate to the Malpighian tubules, and develop through L2 to infective L3 larvae over an extrinsic incubation period typically lasting 8-14 days at optimal temperatures of 25-27°C.[25] The L3 larvae then migrate to the mosquito's proboscis and are deposited onto the skin of a new host during subsequent blood feeding, where they penetrate the bite wound to initiate infection.[5] Vector competence is influenced by environmental factors, particularly temperature and humidity, which affect the extrinsic incubation period and mosquito survival.[7] Development of larvae requires temperatures above a 14°C threshold, with approximately 130 degree-days needed to complete the L1-to-L3 molt; lower temperatures prolong or halt this process.[26] High humidity supports mosquito longevity and activity, enhancing transmission potential, while dry conditions reduce vector populations.[7] Transmission dynamics exhibit strong seasonality, peaking during warmer months when mosquito populations are highest and temperatures favor larval development.[27] In temperate regions, the transmission period often spans late spring to early fall, with potential for overwintering in diapausing adult mosquitoes of species like Culex pipiens, which may harbor arrested L3 larvae until spring.[28] In tropical areas, year-round transmission occurs due to consistent vector presence.[27] The geographic distribution of competent vectors closely aligns with D. immitis endemicity, primarily in tropical and subtropical zones where Aedes and Culex species thrive in warm, humid environments.[7] For instance, Aedes taeniorhynchus predominates in coastal southeastern U.S. and Caribbean hotspots, while Culex pipiens facilitates spread in Europe and urban areas.[24] Climate-driven shifts in vector ranges are expanding transmission risks northward and into previously non-endemic regions.[7]Distribution and Epidemiology

Geographic Range

_Dirofilaria immitis, the causative agent of heartworm disease, exhibits a cosmopolitan distribution primarily in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions worldwide, with established presence across the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. In the Americas, the parasite is endemic throughout North and South America, including all 50 states in the United States where cases have been reported, with the southeastern United States serving as a core area of persistence.[1][29] In Europe, it is prevalent in Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Spain, Greece, and France, as well as eastern and central regions including Poland.[30] Across Asia, occurrences are noted in diverse locales including Japan, while in Africa, distribution remains more limited but present in various countries. Australia also harbors endemic foci, contributing to the global pattern.[1][31] The parasite's spread to the New World is historically linked to international trade and animal movement, with the first documented case in the United States reported in 1847, following its initial description in Italy in 1626. Over the 20th and 21st centuries, globalization and transport networks have facilitated its expansion beyond traditional boundaries.[32][7] Climate change has driven notable shifts in distribution, enabling northward expansion in both the United States and Europe during the 2020s, as warmer temperatures support vector mosquito survival in previously unsuitable areas. Recent reports indicate emergence in cooler climates, including southern Canada where endemic pockets exist in provinces like Ontario and Quebec, and northern European countries such as those in the Baltic region.[31][33][34] Zoonotic transmission hotspots align with high canine infection areas, particularly the southern United States, where environmental conditions favor sustained cycles involving mosquito vectors. Geographic information systems (GIS) have been instrumental in mapping these endemic zones, integrating climate, vector, and host data to delineate risk areas globally.[35][1]Prevalence and Risk Factors

_Dirofilaria immitis infection prevalence in dogs varies widely by region, with rates in the United States ranging from 1% to 12% overall, but reaching up to 25 cases per clinic in highly endemic southern states like Mississippi and Louisiana according to the American Heartworm Society's 2022 incidence survey. In cats, prevalence is substantially lower, estimated at 0.4% nationally, representing approximately 5% to 20% of the canine rate in the same geographic areas. These figures are derived from aggregated testing data from thousands of veterinary practices and shelters, highlighting the parasite's higher burden in canine populations as the primary reservoir.[29][36][37][38] Key risk factors for infection include environmental conditions that favor mosquito vectors, such as warm, humid climates with temperatures consistently above 50°F (10°C) for extended periods, which enable the parasite's larval development within the insect host. Dogs with outdoor lifestyles, particularly hunting or working breeds, face elevated risks due to increased mosquito exposure, while lack of preventive medication—with compliance rates varying but often below 60% for consistent use, according to recent surveys—exacerbates vulnerability across all ages, though younger animals under two years old show higher infection rates in some studies. Age and ecological zone also influence susceptibility, with immature dogs and those in tropical or subtropical zones demonstrating greater odds of infection.[5][39][40][36][41][42][43] Epidemiological trends indicate a steady increase in heartworm incidence across the U.S. over the past two decades, with the AHS's triennial surveys documenting a 22-year upward trajectory, including expansions into previously low-risk northern and western areas attributed to climate change and pet travel. The 2025 CAPC forecast predicts continued high risk in the Southeast with northward creep along the Mississippi River and Atlantic coast, and emerging risks in northern California, the Rocky Mountains, and northern Plains states. National monitoring programs like the AHS Incidence Maps, updated every three years using antigen testing data from over 5,000 clinics, provide essential surveillance for tracking these shifts and informing prevention strategies. Post-disaster events, such as hurricanes, have triggered localized spikes; for instance, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, up to 60% of evacuated dogs tested positive, driven by stagnant water breeding mosquito surges and disrupted prophylaxis.[44][45][29][46][47][48][49]Hosts

Natural and Accidental Hosts

Dirofilaria immitis primarily infects members of the family Canidae as natural hosts, with the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) serving as the principal definitive host in which the parasite undergoes full sexual reproduction and microfilarial production to complete its life cycle.[50] Wild canids, including coyotes (Canis latrans), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and wolves (Canis lupus), function as key reservoir hosts that sustain enzootic transmission cycles, particularly in rural and peri-urban environments where mosquito vectors are prevalent.[50] Accidental hosts encompass a broader range of mammals where infection occurs but the parasite does not typically complete its reproductive cycle. Domestic cats (Felis catus) and ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) can harbor developing larvae or limited numbers of immature adults, though microfilariae production is rare or absent. Other species, such as sea lions (Zalophus californianus) and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), have documented natural infections, while humans (Homo sapiens) act as dead-end hosts in which larvae migrate to the pulmonary arteries but fail to mature or reproduce.[51][1] The host range of D. immitis includes over 30 mammalian species susceptible to infection via mosquito vectors, but reproductive success—marked by adult worm maturation and microfilarial release— is restricted to canids.[52][51][50] In experimental studies, partial larval development has been demonstrated in non-canid models, including rodents such as NOD-scid IL2Rgamma null (NSG) mice, which support worm survival for several weeks, and primates like rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), which exhibit variable susceptibility and host responses to inoculated larvae.[53][54]Host Specificity and Susceptibility

_Dirofilaria immitis demonstrates a restricted host range, achieving full reproductive success primarily in canids such as dogs, with partial development in felids and ferrets, due to differences in host immune compatibility during larval migration and establishment. Infective third-stage larvae (L3) evade initial host defenses through the release and shedding of surface antigens, including 6-kDa and 35-kDa proteins, which reduce antigenicity and modulate immune recognition, facilitating migration from the skin to the pulmonary vasculature in permissive hosts.[55][56] Parasite-derived molecules, such as excretory/secretory proteins and microRNAs, further subvert host innate and adaptive immunity by targeting key pathways, allowing higher larval survival rates in canids compared to other mammals.[57][58] Susceptibility varies markedly across species, with dogs serving as highly permissive hosts where most L3 larvae successfully molt to adults in the pulmonary arteries, supporting microfilaremia and transmission. In contrast, cats act as restrictive hosts, where immune responses lead to high larval mortality during the L3-to-L5 transition, resulting in few or no mature adults; this is attributed to stronger eosinophil-mediated and Th2-biased reactions that clear parasites before vascular establishment.[57][51] Ferrets show intermediate susceptibility, with variable adult worm burdens depending on infection intensity.[57] Genetic factors influencing susceptibility in dogs are not well-defined, though polymorphisms in genes like ABCB1 (MDR1) affect responses to preventive drugs rather than inherent infection risk.[19] Age plays a role, with puppies exhibiting greater vulnerability due to immature immune systems that fail to mount effective early responses against migrating larvae, leading to higher establishment rates despite overall lower prevalence from shorter exposure time.[59] No consistent sex bias is evident, though some studies report slightly higher infection rates in males, possibly linked to behavioral exposure differences rather than immunological factors.[60] Cross-species barriers are pronounced in humans, accidental dead-end hosts, where L3 larvae migrate to the lungs but succumb to immune-mediated destruction without maturing, often forming coin lesions via granulomatous inflammation.[61][11] This abortive development underscores the parasite's adaptation to canid physiology, with human complement and antibody responses rapidly immobilizing and killing larvae post-injection.[11]Pathogenesis

Infection Course in Primary Hosts

The infection of Dirofilaria immitis in dogs, the primary host, commences when infective third-stage larvae (L3) are inoculated into the skin through the bite of an infected mosquito. These larvae initially penetrate the dermis and migrate to subcutaneous tissues, where they undergo the first molt to fourth-stage larvae (L4) as early as day 3 post-infection, typically completing this by days 9–12.[62] During this phase, the L4 larvae continue migrating through subcutaneous and muscular tissues for approximately 50–70 days before entering the venous circulation and reaching the pulmonary arteries. This migration period is generally asymptomatic, with no overt clinical signs in the host.[5] Upon arriving in the pulmonary arteries around 70 days post-infection, the L4 larvae molt to immature adults and begin maturing over the next 2–3 months, reaching young adult stage by 3–4 months after initial inoculation.[4] At this point, the worms, now 10–15 cm in length, reside primarily in the pulmonary arteries and may extend into the right ventricle as they grow.[4] Maturation to fully fertile adults occurs by 6–7 months post-infection, when worms attain lengths of 15–30 cm for females and 12–20 cm for males; mating then ensues, with female worms producing microfilariae asynchronously starting around the prepatent period of 6.5–7 months.[62] These microfilariae are released by gravid female worms into the bloodstream and enter the peripheral circulation, circulating at low levels initially (peaking at 1,000–100,000 per mL of blood) and persisting for the adult worms' lifespan of 5–7 years unless cleared by immune responses or treatment. The progression of disease severity in dogs is classified into four stages based on adult worm burden and associated pathology, reflecting the cumulative host-parasite interactions, as per the American Heartworm Society guidelines (updated 2024).[63] Class 1 (mild) involves low worm burdens (up to about 5 adult worms), typically resulting in minimal or no clinical signs and limited vascular endothelial irritation. Class 2 (moderate) features worm burdens of approximately 5–40, leading to moderate pulmonary vascular changes such as intimal proliferation and mild thrombosis without overt symptoms. In Class 3 (severe), with worm burdens >40, significant vascular remodeling occurs, including fibrosis, arteritis, and pulmonary hypertension due to mechanical obstruction and inflammatory responses to worm antigens. Class 4 (caval syndrome), characterized by very high worm burdens (>40 with worms migrating to the right heart and vena cava), represents critical caval syndrome, where worms migrate to the right heart and vena cava, causing severe hemodynamic compromise and rapid vascular damage. Microfilariae production is not synchronous across all females, contributing to fluctuating peripheral levels that may evade detection in some infections. Occult (amicrofilaremic) infections arise in a variable proportion of cases (reported from 10–70% depending on population), often due to single-sex worm populations, host immune-mediated clearance of microfilariae, or prepatent interruptions, yet still drive progressive vascular pathology from adult worms.[62] Throughout the course, initial host tolerance allows asymptomatic establishment, but accumulating worm burden elicits immune-mediated endothelial activation, thrombus formation, and gradual transition to chronic pulmonary vascular disease.[4]Role of Wolbachia pipientis

Wolbachia pipientis is an obligate endosymbiotic bacterium belonging to the order Rickettsiales that resides within the tissues of Dirofilaria immitis, primarily in the hypodermis, lateral cords, and reproductive organs of both male and female worms. This symbiosis is mutualistic, with the bacteria providing essential nutrients and cofactors, such as heme and riboflavin, that support the parasite's survival and development. Without Wolbachia, D. immitis exhibits impaired embryogenesis, reduced microfilarial production, and disrupted larval molting, rendering the worms infertile and less viable.[64][65] The bacterium contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of heartworm disease by eliciting host immune responses. Wolbachia surface proteins and other antigens provoke intense inflammation in the host, particularly in the pulmonary arteries and lungs, exacerbating tissue damage beyond that caused by the worms alone. Upon the death of adult worms or during microfilarial turnover, massive release of Wolbachia into the bloodstream triggers severe hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis-like symptoms and chronic inflammatory lesions, which can lead to pulmonary thromboembolism.[66][67] Treatment strategies targeting Wolbachia have revolutionized heartworm management. Administration of doxycycline, an antibiotic that depletes the bacterial load, sterilizes female worms by halting microfilarial production and reduces the inflammatory risks associated with worm elimination; a typical regimen involves 10 mg/kg orally twice daily for 4 weeks.[63] This approach not only enhances the efficacy of adulticidal therapies like melarsomine but also mitigates post-treatment complications from bacterial release.[64][68] Evolutionarily, Wolbachia pipientis is maternally transmitted within filarial nematodes, ensuring its persistence across generations through vertical inheritance via oocytes. This mode of transmission has co-evolved with the host, where the absence of Wolbachia in certain filarial species correlates with infertility and developmental arrest, underscoring its indispensable role in nematode reproductive biology.[67][65] Recent research in the 2020s has advanced understanding through genomic analyses of Wolbachia in D. immitis, revealing strain-specific adaptations and potential drug targets. Studies on nucleotide composition and gene expression have highlighted how bacterial genome streamlining influences symbiotic interactions, paving the way for novel anti-Wolbachia therapies that could provide macrofilaricidal effects without the toxicity of traditional treatments. Phylogenetic and immunogenic profiling of surface proteins suggests opportunities for vaccine development against filarial diseases.[69][70]Clinical Manifestations

Signs in Dogs

Heartworm disease in dogs is classified into four stages based on the severity of infection and clinical manifestations, primarily determined by the worm burden and its impact. Class 1 represents mild infection with a low worm burden, where dogs are often asymptomatic or exhibit only subtle signs such as an occasional cough, allowing the disease to go undetected for extended periods.[5] In Class 2 (moderate infection with a moderate worm burden), mild to moderate symptoms emerge, including coughing, exercise intolerance, fatigue after moderate activity, and occasional weight loss, reflecting early pulmonary involvement.[5] Progression to Class 3 (severe infection with a high worm burden) intensifies these signs, with persistent coughing, significant exercise intolerance, rapid weight loss, labored breathing, and signs of right-sided heart failure such as ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen), indicating advanced vascular and cardiac strain.[19] The most critical manifestation occurs in Class 4, known as caval syndrome, where a large number of worms migrate into the right ventricle and vena cava, leading to acute collapse, severe weakness, hemoglobinuria (dark, bloody urine from red blood cell destruction), pale mucous membranes, and rapid deterioration often resulting in death without intervention.[50] Secondary effects exacerbate the disease, including pulmonary hypertension from endothelial damage and worm emboli, which can cause thromboembolism and sudden respiratory distress or syncope.[71] Chronic progression may lead to cor pulmonale, characterized by right ventricular enlargement and failure due to sustained pulmonary hypertension, along with multi-organ damage from hypoxia and inflammation.[72] Susceptibility to severe signs varies by breed, with smaller dogs experiencing more pronounced symptoms at lower worm burdens due to limited vascular space, while larger breeds may tolerate higher loads before clinical evidence appears.[73]Signs in Cats and Other Species

In cats, Dirofilaria immitis infection often manifests as heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD), primarily triggered by the death of immature larvae rather than adult worms, leading to acute respiratory inflammation.[74] Common signs include coughing, dyspnea, vomiting, anorexia, lethargy, and exercise intolerance, with cats typically harboring only 1-3 adult worms and rarely producing microfilariae.[75][50] Unlike dogs, cats exhibit heightened sensitivity to even low worm burdens, resulting in more abrupt and severe respiratory distress.[76] Chronic feline heartworm disease can involve right ventricular enlargement due to pulmonary hypertension and potential thromboembolism from dying worms, contributing to progressive heart failure with signs such as labored breathing, weight loss, and abdominal distention.[19] Untreated cases carry a high mortality risk, with median survival times ranging from 1.5 to 4 years, and sudden death possible from acute collapse.[75] Veterinary surveys from the 2020s, including data as of 2024, indicate rising feline cases in urban and previously low-prevalence areas, linked to increased mosquito activity, climate change, and proximity to canine reservoirs.[46][77][78][79] In ferrets, a highly susceptible accidental host, even a single worm can cause severe disease with rapid onset, including anorexia, dyspnea, weakness, rapid heartbeat, and sudden collapse or death.[80][81] Signs often progress quickly to fluid accumulation in the abdomen or chest and overall depression.[82] Wildlife species such as coyotes and foxes serve as asymptomatic reservoirs, typically showing no overt clinical signs despite harboring adult worms that sustain transmission cycles.[83] Human infections, acquired as dead-end hosts, are usually asymptomatic but may present as solitary pulmonary nodules (coin lesions) from larval embolization, occasionally with cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, fever, or mild respiratory distress.[61] Equine infections are rare but can be severe, featuring acute signs like dyspnea, vomiting, convulsions, syncope, and sudden death, or chronic respiratory issues including coughing and exercise intolerance.[33]Diagnosis

Laboratory Methods

Laboratory diagnosis of Dirofilaria immitis primarily involves detecting microfilariae in blood or identifying parasite antigens and DNA, with methods selected based on the infection stage and suspected load.[84] Microfilariae, the first larval stage released by adult female worms, become detectable in the blood during the patent phase of infection, typically 6 to 7 months after larval inoculation by mosquitoes.[85] This timing aligns with the maturation of larvae into adults in the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle, as detailed in the pathogenesis section. Detection of microfilariae relies on microscopic examination of blood samples, often requiring concentration techniques due to low numbers in early or light infections. The direct smear method involves placing a drop of blood on a slide and examining it under a microscope, but it has low sensitivity, detecting microfilariae in only about 20-50% of positive cases depending on parasitemia levels.[86] To improve detection, the Knott's test uses formalin lysis to concentrate microfilariae from 1 mL of anticoagulated blood, followed by centrifugation and staining with methylene blue for morphological identification; this method achieves higher sensitivity, up to 80-90% in microfilaremic dogs.[87] Similarly, the hematocrit tube concentration technique employs centrifugation of blood-filled capillary tubes to pellet microfilariae at the bottom, allowing visualization after staining, and offers comparable sensitivity to Knott's with the advantage of requiring smaller sample volumes (about 0.2 mL).[86] Antigen detection tests target circulating proteins produced primarily by adult female worms, providing evidence of mature infections even in the absence of microfilariae. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, such as those detecting heartworm antigen in serum or plasma, exhibit high sensitivity (over 90%, often 98%) and specificity (100%) for infections with at least one female adult worm, making them a cornerstone of routine screening.[88] These tests are particularly useful pre-patent or in amicrofilaremic cases but may yield false negatives in low-worm-burden infections or those dominated by males.[85] Molecular methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enable sensitive detection of D. immitis DNA in blood or tissue samples, proving valuable for confirming occult infections where microfilariae or antigens are undetectable. Real-time PCR assays targeting mitochondrial or ribosomal genes can identify as few as 1-10 microfilariae per mL and distinguish D. immitis from co-circulating filariae.[89] For instance, multiplex PCR protocols simultaneously detect D. immitis and its endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis, enhancing diagnostic accuracy in complex cases.[90] Differentiation of D. immitis microfilariae from those of non-pathogenic species like Acanthocheilonema reconditum (formerly Dipetalonema reconditum) is essential to avoid misdiagnosis, as both may appear in canine blood. Morphologically, D. immitis microfilariae are longer (287-325 μm) and sheathed with a tapered anterior end, while A. reconditum are unsheathed, shorter (260-296 μm), and have a blunt head; these features are best assessed after concentration and staining in Knott's preparations.[13] PCR provides definitive species identification by amplifying unique genetic sequences, resolving ambiguities in morphological assessments.[91] Proper sample handling is critical for reliable results. Blood for microfilariae detection should be collected in EDTA tubes to prevent clotting, stored at 4°C, and processed within 24 hours to maintain microfilariae viability; refrigeration extends usability up to 5 days.[92] Antigen tests require serum or plasma, ideally separated promptly and frozen if not tested immediately. Testing is most informative after the prepatent period, as early sampling may yield false negatives.[85]Imaging and Serological Tests

Imaging and serological tests play a crucial role in diagnosing Dirofilaria immitis infections, particularly in detecting structural changes and immune responses that complement direct parasite identification. Thoracic radiography is a primary imaging modality, revealing characteristic signs such as enlargement of the main pulmonary arteries, tortuous vessels, and pulmonary parenchymal infiltrates in infected dogs. These radiographic findings are more pronounced in moderate to heavy infections, with a reported sensitivity of approximately 80% for detecting significant worm burdens. Echocardiography provides direct visualization of adult worms in the right ventricle and pulmonary arteries, appearing as parallel linear echodensities, and is especially valuable when serological antigen tests are negative but clinical suspicion remains high. Its sensitivity for worm detection varies, ranging from 45% to higher values in experimental settings with multiple worms, though it offers high specificity for confirmation once worms are observed. Advanced imaging techniques enhance diagnostic precision, particularly in atypical or human cases. In dogs, ultrasound can visualize live worms in accessible sites, while computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are employed in humans to identify pulmonary nodules or coin lesions caused by embolized worm segments, often mimicking malignancy. For instance, CT scans delineate the size and location of these nodules, aiding differentiation from tumors. Serological tests distinguish between active infection and exposure: antigen tests detect circulating antigens from adult female worms with high sensitivity (79% to 100%) and specificity (near 100%), making them reliable for confirming patent infections in dogs. In contrast, antibody tests indicate exposure to larval stages but are less specific, as they may remain positive post-infection clearance, and are particularly useful in cats where antigen tests have lower sensitivity due to single-sex or immature infections. In cats, combining antigen and antibody tests is recommended to achieve maximum diagnostic sensitivity, as antigen tests alone may miss immature or single-worm infections.[93]Treatment

Protocols for Dogs

The treatment of heartworm disease in dogs primarily involves a multimodal approach aimed at eliminating adult worms (adulticide therapy), microfilariae (microfilaricide therapy), and managing associated inflammation and complications, as recommended by the American Heartworm Society (AHS). Melarsomine dihydrochloride is the only FDA-approved adulticide for this purpose and is administered via the three-dose protocol to achieve high efficacy while minimizing risks. This protocol consists of a single deep intramuscular injection of 2.5 mg/kg in the lumbar paraspinal muscles approximately one month after completing doxycycline (around day 60 from diagnosis), followed by two injections (2.5 mg/kg each) 24 hours apart approximately one month later (around days 90 and 91).[21] [63] The three-dose regimen kills over 98% of adult worms within a controlled timeframe, outperforming the alternative two-dose protocol (days 1 and 30), which achieves approximately 90% efficacy.[94] Prior to melarsomine administration, pre-treatment with doxycycline is strongly recommended to target Wolbachia pipientis, the bacterial endosymbiont essential for worm viability, thereby enhancing adulticide efficacy and reducing inflammatory responses. The standard regimen is 10 mg/kg orally twice daily for 28 consecutive days, ideally initiated at diagnosis alongside a macrocyclic lactone (ML) preventive to stabilize the patient, followed by a one-month wait before the first melarsomine dose.[62] [63] If doxycycline is unavailable or not tolerated, minocycline at 5 mg/kg orally twice daily for 28 days serves as an effective alternative, with comparable results in reducing worm burdens when combined with the melarsomine protocol.[63] This pre-treatment step, updated in the 2024 AHS guidelines, underscores the role of Wolbachia depletion in safer, more effective therapy. Following the first melarsomine injection (or concurrently if microfilariae are present at diagnosis), microfilaricide therapy is implemented to clear circulating larvae and prevent transmission. Low-dose monthly MLs, such as ivermectin at 6-12 μg/kg orally or milbemycin oxime at the heartworm preventive dose, are used starting one month after the initial melarsomine dose and continued for at least 6-9 months post-treatment.[21] This approach safely eliminates microfilariae over 1-2 months without the risks associated with higher-dose milbemycin, which can cause severe reactions in microfilaremic dogs. Microfilaria testing is repeated 6 months after treatment completion to confirm clearance. Supportive care is integral to mitigate treatment risks and promote recovery. Strict exercise restriction—confining dogs to crate rest or short leash walks—is enforced for at least 8 weeks following each melarsomine injection to reduce pulmonary arterial pressure and prevent worm fragments from embolizing.[95] Corticosteroids, such as prednisone at 0.5-1 mg/kg orally twice daily tapered over 10-14 days, may be administered if signs of pulmonary inflammation (e.g., coughing, lethargy) occur, particularly in moderate to severe cases.[94] The AHS classifies dogs into stages 1 (asymptomatic/mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe/caval syndrome) based on clinical signs, radiographs, and echocardiography to assess worm burden and tailor supportive measures; higher burdens (e.g., >50 worms) warrant more cautious monitoring.[63] Complications, notably post-treatment pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), arise from dying worms fragmenting and obstructing pulmonary vessels, potentially leading to acute respiratory distress or right-sided heart failure. The risk is highest 7-10 days after injections and in dogs with heavy worm burdens, but adherence to the full AHS protocol, including pre-treatment and exercise restriction, significantly lowers incidence. In a large retrospective study of 626 dogs, overall treatment-related mortality was 1.3%, with most deaths linked to PTE in unmanaged severe cases.[96] Monitoring includes serial radiographs and clinical exams; anticoagulants like aspirin (5-10 mg/kg every 48 hours) may be considered prophylactically in high-risk stage 3 dogs, though evidence for routine use is limited.[97] The AHS 2024 guidelines endorse the "fast-kill" melarsomine-based approach as the gold standard for rapid worm elimination and disease resolution, contrasting with the "slow-kill" method using monthly MLs alone (e.g., ivermectin 6 μg/kg), which gradually reduces adult worms over 12-36 months but prolongs vascular pathology and increases PTE risk due to persistent worm activity.[98] Slow-kill is reserved for cases where melarsomine is contraindicated (e.g., financial constraints or owner refusal), with doxycycline added for enhanced adulticidal effects. Post-treatment antigen testing at 6-9 months confirms success, with retreatment if positive.[99]| Treatment Phase | Key Components | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment Stabilization | Doxycycline 10 mg/kg PO BID; ML preventive (e.g., ivermectin 6 μg/kg PO monthly) | Days 1-28 (start at diagnosis), followed by 1-month wait |

| Adulticide Injections | Melarsomine 2.5 mg/kg IM (deep lumbar) | ~Day 60 (1 dose); ~Days 90-91 (2 doses, 24h apart) |

| Microfilaricide | Low-dose ML (ivermectin 6-12 μg/kg PO or milbemycin equivalent) | Monthly, starting ~1 month after first melarsomine; continue 6-9 months total |

| Supportive Care | Exercise restriction; corticosteroids if needed (prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg PO BID, taper) | 8 weeks post each injection; as indicated for inflammation |

| Follow-up | Antigen and microfilaria tests | 6-9 months post-final injection |