Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Triple-alpha process

View on Wikipedia

The triple-alpha process is a set of nuclear fusion reactions by which three helium-4 nuclei (alpha particles) are transformed into carbon.[1][2]

In stars

[edit]

Helium accumulates in the cores of stars as a result of the proton–proton chain reaction and the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen cycle.

Nuclear fusion reactions of two helium-4 nuclei produces beryllium-8, which is highly unstable, and decays back into smaller nuclei with a half-life of 8.19×10−17 s, unless within that time a third alpha particle fuses with the beryllium-8 nucleus[3] to produce an excited resonance state of carbon-12,[4] called the Hoyle state. This nearly always decays back into three alpha particles, but once in about 2421.3 times, it releases energy and changes into the stable base form of carbon-12.[5] When a star runs out of hydrogen to fuse in its core, it begins to contract and heat up. If the central temperature rises to 108 K,[6] six times hotter than the Sun's core, alpha particles can fuse fast enough to get past the beryllium-8 barrier and produce significant amounts of stable carbon-12.

The net energy release of the process is 7.275 MeV.

As a side effect of the process, some carbon nuclei fuse with additional helium to produce a stable isotope of oxygen and energy:

Nuclear fusion reactions of helium with hydrogen produces lithium-5, which also is highly unstable, and decays back into smaller nuclei with a half-life of 3.7×10−22 s.

Fusing with additional helium nuclei can create heavier elements in a chain of stellar nucleosynthesis known as the alpha process, but these reactions are only significant at higher temperatures and pressures than in cores undergoing the triple-alpha process. This creates a situation in which stellar nucleosynthesis produces large amounts of carbon and oxygen, but only a small fraction of those elements are converted into neon and heavier elements. Oxygen and carbon are the main "ash" of helium-4 burning.

In neutron stars

[edit]Material that accretes from a companion star onto the surface of a neutron star may begin this helium-burning process in a local region. The burning wave is estimated to travel at 50 to 500 km/s, traversing the surface in around one second. Within this second, the neutron star rapidly rotates, moving the brighter burning region in and out of view. This intensity modulation allows the rotational frequency to be measured, sometimes up to 300 Hz.

Some neutron stars have been measured with such an intensity modulation at 600 Hz. A suggested origin is neutron stars which rotate at 300 Hz, but have two burning regions. The second burning region is theorized to form almost immediately after the first, exactly on the opposite side of the neutron star, due to the convergence of gravitational wave from the initial thermonuclear ignition.[7]

Primordial carbon

[edit]The triple-alpha process is ineffective at the pressures and temperatures early in the Big Bang. One consequence of this is that no significant amount of carbon was produced in the Big Bang.

Resonances

[edit]Ordinarily, the probability of the triple-alpha process is extremely small. However, the beryllium-8 ground state has almost exactly the energy of two alpha particles. In the second step, 8Be + 4He has almost exactly the energy of an excited state of 12C. This resonance greatly increases the probability that an incoming alpha particle will combine with beryllium-8 to form carbon. The existence of this resonance was predicted by Fred Hoyle before its observation, based on the physical necessity for it to exist, in order for carbon to be formed in stars. The prediction and then discovery of this energy resonance and process supported Hoyle's hypothesis of stellar nucleosynthesis, which posited that all chemical elements had originally been formed from hydrogen, the true primordial substance. The anthropic principle has been cited to explain the fact that nuclear resonances are sensitively arranged to create large amounts of carbon and oxygen in the universe.[8][9]

Reaction rate and stellar evolution

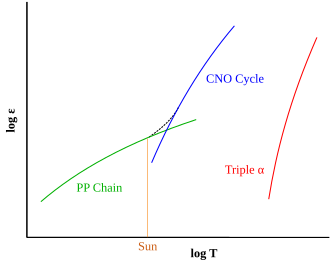

[edit]The triple-alpha steps are strongly dependent on the temperature and density of the stellar material. The power released by the reaction is approximately proportional to the temperature to the 40th power, and the density squared.[10] In contrast, the proton–proton chain reaction produces energy at a rate proportional to the fourth power of temperature, the CNO cycle at about the 17th power of the temperature, and both are linearly proportional to the density. This strong temperature dependence has consequences for the late stage of stellar evolution, the red-giant stage.

For lower mass stars on the red-giant branch, the helium accumulating in the core is prevented from further collapse only by electron degeneracy pressure. The entire degenerate core is at the same temperature and pressure, so when its density becomes high enough, fusion via the triple-alpha process rate starts throughout the core. The core is unable to expand in response to the increased energy production until the pressure is high enough to lift the degeneracy. As a consequence, the temperature increases, causing an increased reaction rate in a positive feedback cycle that becomes a runaway reaction. This process, known as the helium flash, lasts a matter of seconds but burns 60–80% of the helium in the core. During the core flash, the star's energy production can reach approximately 1011 solar luminosities which is comparable to the luminosity of a whole galaxy,[11] although no effects will be immediately observed at the surface, as the whole energy is used up to lift the core from the degenerate to normal, gaseous state. Since the core is no longer degenerate, hydrostatic equilibrium is once more established and the star begins to "burn" helium at its core and hydrogen in a spherical layer above the core. The star enters a steady helium-burning phase which lasts about 10% of the time it spent on the main sequence (the Sun is expected to burn helium at its core for about a billion years after the helium flash).[12]

In higher mass stars, which evolve along the asymptotic giant branch, carbon and oxygen accumulate in the core as helium is burned, while hydrogen burning shifts to further-out layers, resulting in an intermediate helium shell. However, the boundaries of these shells do not shift outward at the same rate due to differing critical temperatures and temperature sensitivities for hydrogen and helium burning. When the temperature at the inner boundary of the helium shell is no longer high enough to sustain helium burning, the core contracts and heats up, while the hydrogen shell (and thus the star's radius) expand outward. Core contraction and shell expansion continue until the core becomes hot enough to reignite the surrounding helium. This process continues cyclically – with a period on the order of 1000 years – and stars undergoing this process have periodically variable luminosity. These stars also lose material from their outer layers in a stellar wind driven by radiation pressure, which ultimately becomes a superwind as the star enters the planetary nebula phase.[13]

Discovery

[edit]The triple-alpha process is highly dependent on carbon-12 and beryllium-8 having resonances with slightly more energy than helium-4. Based on known resonances, by 1952 it seemed impossible for ordinary stars to produce carbon as well as any heavier element.[14] Nuclear physicist William Alfred Fowler had noted the beryllium-8 resonance, and Edwin Salpeter had calculated the reaction rate for 8Be, 12C, and 16O nucleosynthesis taking this resonance into account.[15][16] However, Salpeter calculated that red giants burned helium at temperatures of 2·108 K or higher, whereas other recent work hypothesized temperatures as low as 1.1·108 K for the core of a red giant.

Salpeter's paper mentioned in passing the effects that unknown resonances in carbon-12 would have on his calculations, but the author never followed up on them. It was instead astrophysicist Fred Hoyle who, in 1953, used the abundance of carbon-12 in the universe as evidence for the existence of a carbon-12 resonance. The only way Hoyle could find that would produce an abundance of both carbon and oxygen was through a triple-alpha process with a carbon-12 resonance near 7.68 MeV, which would also eliminate the discrepancy in Salpeter's calculations.[14]

Hoyle went to Fowler's lab at Caltech and said that there had to be a resonance of 7.68 MeV in the carbon-12 nucleus. (There had been reports of an excited state at about 7.5 MeV.[14]) Fred Hoyle's audacity in doing this is remarkable, and initially, the nuclear physicists in the lab were skeptical. Finally, a junior physicist, Ward Whaling, fresh from Rice University, who was looking for a project decided to look for the resonance. Fowler permitted Whaling to use an old Van de Graaff generator that was not being used. Hoyle was back in Cambridge when Fowler's lab discovered a carbon-12 resonance near 7.65 MeV a few months later, validating his prediction. The nuclear physicists put Hoyle as first author on a paper delivered by Whaling at the summer meeting of the American Physical Society. A long and fruitful collaboration between Hoyle and Fowler soon followed, with Fowler even coming to Cambridge.[17]

The final reaction product lies in a 0+ state (spin 0 and positive parity). Since the Hoyle state was predicted to be either a 0+ or a 2+ state, electron–positron pairs or gamma rays were expected to be seen. However, when experiments were carried out, the gamma emission reaction channel was not observed, and this meant the state must be a 0+ state. This state completely suppresses single gamma emission, since single gamma emission must carry away at least 1 unit of angular momentum. Pair production from an excited 0+ state is possible because their combined spins (0) can couple to a reaction that has a change in angular momentum of 0.[18]

Improbability and fine-tuning

[edit]Carbon is a necessary component of all known life. 12C, a stable isotope of carbon, is abundantly produced in stars due to three factors:

- The decay lifetime of a 8Be nucleus is four orders of magnitude larger than the time for two 4He nuclei (alpha particles) to scatter.[19]

- An excited state of the 12C nucleus exists a little (0.3193 MeV) above the energy level of 8Be + 4He. This is necessary because the ground state of 12C is 7.3367 MeV below the energy of 8Be + 4He; a 8Be nucleus and a 4He nucleus cannot reasonably fuse directly into a ground-state 12C nucleus. However, 8Be and 4He use the kinetic energy of their collision to fuse into the excited 12C (kinetic energy supplies the additional 0.3193 MeV necessary to reach the excited state), which can then transition to its stable ground state. According to one calculation, the energy level of this excited state must be between about 7.3 MeV and 7.9 MeV to produce sufficient carbon for life to exist, and must be further "fine-tuned" to between 7.596 MeV and 7.716 MeV in order to produce the abundant level of 12C observed in nature.[20] The Hoyle state has been measured to be about 7.65 MeV above the ground state of 12C.[21]

- In the reaction 12C + 4He → 16O, there is an excited state of oxygen which, if it were slightly higher, would provide a resonance and speed up the reaction. In that case, insufficient carbon would exist in nature; almost all of it would have converted to oxygen.[19]

Some scholars argue the 7.656 MeV Hoyle resonance, in particular, is unlikely to be the product of mere chance. Fred Hoyle argued in 1982 that the Hoyle resonance was evidence of a "superintellect";[14] Leonard Susskind in The Cosmic Landscape rejects Hoyle's intelligent design argument.[22] Instead, some scientists believe that different universes, portions of a vast "multiverse", have different fundamental constants:[23] according to this controversial fine-tuning hypothesis, life can only evolve in the minority of universes where the fundamental constants happen to be fine-tuned to support the existence of life. Other scientists reject the hypothesis of the multiverse on account of the lack of independent evidence.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Appenzeller; Harwit; Kippenhahn; Strittmatter; Trimble, eds. (1998). Astrophysics Library (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W. & Ostlie, Dale A. (2007). An Introduction to Modern Stellar Astrophysics. Addison Wesley, San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-8053-0348-3.

- ^ Bohan, Elise; Dinwiddie, Robert; Challoner, Jack; Stuart, Colin; Harvey, Derek; Wragg-Sykes, Rebecca; Chrisp, Peter; Hubbard, Ben; Parker, Phillip; et al. (Writers) (February 2016). Big History. Foreword by David Christian (1st American ed.). New York: DK. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4654-5443-0. OCLC 940282526.

- ^ Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3) 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ^ The carbon challenge, Morten Hjorth-Jensen, Department of Physics and Center of Mathematics for Applications, University of Oslo, N-0316 Oslo, Norway: 9 May 2011, Physics 4, 38

- ^ Wilson, Robert (1997). "Chapter 11: The Stars – their Birth, Life, and Death". Astronomy through the ages the story of the human attempt to understand the universe. Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203212738.

- ^ Simonenko, Vadim A. (2006). "Nuclear explosions as a probing tool for high-intensity processes and extreme states of matter: some applications of results". Physics-Uspekhi. 49 (8): 861. doi:10.1070/PU2006v049n08ABEH006080. ISSN 1063-7869.

- ^ For example, John Barrow; Frank Tipler (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle.

- ^ Fred Hoyle, "The Universe: Past and Present Reflections." Engineering and Science, November, 1981. pp. 8–12

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2006). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley, San Francisco. pp. 312–313. ISBN 978-0-8053-0402-2.

- ^ Prialnik, Dina (2006). An Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Structure and Evolution (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley, San Francisco. pp. 461–462. ISBN 978-0-8053-0402-2.

- ^ "The End Of The Sun". faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2010). "Thermal pulses and the asymptotic giant branch". An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–173. ISBN 9780521866040.

- ^ a b c d Kragh, Helge (2010) When is a prediction anthropic? Fred Hoyle and the 7.65 MeV carbon resonance. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/5332/

- ^ Salpeter, E. E. (1952). "Nuclear Reactions in Stars Without Hydrogen". The Astrophysical Journal. 115: 326–328. Bibcode:1952ApJ...115..326S. doi:10.1086/145546.

- ^ Salpeter, E. E. (2002). "A Generalist Looks Back". Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40: 1–25. Bibcode:2002ARA&A..40....1S. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.40.060401.093901.

- ^ Fred Hoyle, A Life in Science, Simon Mitton, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pages 205–209.

- ^ Cook, CW; Fowler, W.; Lauritsen, C.; Lauritsen, T. (1957). "12B, 12C, and the Red Giants". Physical Review. 107 (2): 508–515. Bibcode:1957PhRv..107..508C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.107.508.

- ^ a b Uzan, Jean-Philippe (April 2003). "The fundamental constants and their variation: observational and theoretical status". Reviews of Modern Physics. 75 (2): 403–455. arXiv:hep-ph/0205340. Bibcode:2003RvMP...75..403U. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.403. S2CID 118684485.

- ^ Livio, M.; Hollowell, D.; Weiss, A.; Truran, J. W. (27 July 1989). "The anthropic significance of the existence of an excited state of 12C". Nature. 340 (6231): 281–284. Bibcode:1989Natur.340..281L. doi:10.1038/340281a0. S2CID 4273737.

- ^ Freer, M.; Fynbo, H. O. U. (2014). "The Hoyle state in 12C" (PDF). Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 78: 1–23. Bibcode:2014PrPNP..78....1F. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2014.06.001. S2CID 55187000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-18.

- ^ Peacock, John (2006). "A Universe Tuned for Life". American Scientist. 94 (2): 168–170. doi:10.1511/2006.58.168. JSTOR 27858743.

- ^ "Stars burning strangely make life in the multiverse more likely". New Scientist. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Luke A (2012). "The fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent life". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 29 (4): 529–564. arXiv:1112.4647. Bibcode:2012PASA...29..529B. doi:10.1071/as12015.