Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Homeric Question

View on Wikipedia

The Homeric Question concerns the doubts and consequent debate over the identity of Homer, the authorship of the Iliad and Odyssey, and their historicity (especially concerning the Iliad). The subject has its roots in classical antiquity and the scholarship of the Hellenistic period, but has flourished among Homeric scholars of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

The main subtopics of the Homeric Question are:

- "Who is Homer?"[1]

- "Are the Iliad and the Odyssey of multiple or single authorship?"[2]

- "By whom, when, where, and under what circumstances were the poems composed?"[3]

To these questions the possibilities of modern textual criticism and archaeological answers have added a few more:

- "How reliable is the tradition embodied in the Homeric poems?"[4]

- "How old are the oldest elements in Homeric poetry which can be dated with certainty?"[5]

Oral tradition

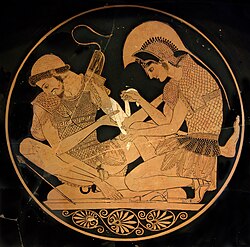

[edit]| Trojan War |

|---|

|

The very forefathers of text criticism, including Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614), Richard Bentley (1662–1742) and Friedrich August Wolf (1759–1824) already emphasized the fluid-like, oral nature of the Homeric canon.[6]

This perspective, however, did not receive mainstream recognition until after the seminal work of Milman Parry in the early 20th century. Now most classicists agree that, whether or not there was ever such a composer as Homer, the poems attributed to him are to some degree dependent on oral tradition, a generations-old technique that was the collective inheritance of many singer-poets (or ἀοιδοί, aoidoi). An analysis of the structure and vocabulary of the Iliad and Odyssey shows that the poems contain many regular and repeated phrases; indeed, even entire verses are repeated. Thus according to the theory, the Iliad and Odyssey may have been products of oral-formulaic composition, composed on the spot by the poet using a collection of memorized traditional verses and phrases. Milman Parry and Albert Lord have pointed out that such elaborate oral tradition, foreign to today's literate cultures, is typical of epic poetry in an exclusively oral culture. The crucial words here are "oral" and "traditional". Parry starts with the former: the repetitive chunks of language, he says, were inherited by the singer-poet from his predecessors, and were useful to him in composition. Parry calls these chunks of repetitive language "formulas".[7]

Many scholars agree that the Iliad and Odyssey underwent a process of standardization and refinement out of older material, beginning in the 8th century BC.[8] This process, often referred to as the "million little pieces" design, seems to acknowledge the spirit of oral tradition. As Albert Lord notes in his book The Singer of Tales, poets within an oral tradition, as was Homer, tend to create and modify their tales as they perform them. Although this suggests that Homer may simply have "borrowed" from other bards, he almost certainly made the piece his own when he performed it.[9]

The 1960 publication of Lord's book, which focused on the problems and questions that arise in conjunction with applying oral-formulaic theory to problematic texts such as the Iliad, the Odyssey and even Beowulf influenced nearly all subsequent work on Homer and oral-formulaic composition. In response to his landmark effort, Geoffrey Kirk published a book entitled The Songs of Homer, in which he questions Lord's extension of the oral-formulaic nature of Serbian epic poetry in Bosnia and Herzegovina (the area from which the theory was first developed) to Homeric epic. He holds that Homeric poems differ from those traditions in their "metrical strictness", "formular system[s]" and creativity. Kirk argued that Homeric poems were recited under a system that gave the reciter much more freedom to choose words and passages to achieve the same end than the Serbian poet, who was merely "reproductive".[10][11]

Shortly afterwards, Eric A. Havelock's 1963 book Preface to Plato revolutionized how scholars looked at Homeric epic by arguing not only that it was the product of an oral tradition but that the oral-formulas contained therein served as a way for ancient Greeks to preserve cultural knowledge across many different generations.[12] In his 1966 work Have we Homer's Iliad?, Adam Parry theorized the existence of the most fully developed oral poet up to his time, a person who could (at his discretion) creatively and intellectually form nuanced characters in the context of the accepted, traditional story; in fact, Parry altogether discounted the Serbian tradition to an "unfortunate" extent, choosing to elevate the Greek model of oral-tradition above all others.[13][14] Lord reacted to Kirk and Parry's respective contentions with Homer as Oral Poet, published in 1968, which reaffirmed his belief in the relevance of Serbian epic poetry and its similarities to Homer, and downplayed the intellectual and literary role of the reciters of Homeric epic.[15]

In further support of the theory that Homer is really the name of a series of oral-formulas, or equivalent to "the Bard" as applied to Shakespeare, the Greek name Homēros is etymologically noteworthy. It is identical to the Greek word for "hostage". It has been hypothesized that his name was back-extracted from the name of a society of poets called the Homeridae, which literally means "sons of hostages", i.e., descendants of prisoners of war. As these men were not sent to war because their loyalty on the battlefield was suspect, they would not be killed in conflicts, so they were entrusted with remembering the area's stock of epic poetry, to remember past events, from the time before literacy came to the area.[16]

In a similar vein, the word "Homer" may simply be a carryover from the Mediterranean seafarers' vocabulary adoption of the Semitic word base 'MR, which means "say" or "tell". "Homer" may simply be the Mediterranean version of "saga". Pseudo-Plutarch suggests that the name comes from a word meaning "to follow" and another meaning "blind".[17] Other sources connect Homer's name with Smyrna for several etymological reasons.[18]

Time frame

[edit]Exactly when these poems would have taken on a fixed written form is subject to debate. The traditional solution is the "transcription hypothesis", wherein a non-literate singer dictates the poem to a literate scribe in the 6th century BC or earlier. Sources from antiquity are unanimous in declaring that Peisistratus, the tyrant of Athens, first committed the poems of Homer to writing and placed them in the order in which we now read them.[8] More radical Homerists, such as Gregory Nagy, contend that a canonical text of the Homeric poems did not exist until established by Alexandrian editors in the Hellenistic period (3rd to 1st century BC).

The modern debate began with the Prolegomena of Friedrich August Wolf (1795). According to Wolf, the date of writing is among the first questions in the textual criticism of Homer. Having satisfied himself that writing was unknown to Homer, Wolf considers the real mode of transmission, which he purports to find in the Rhapsodists, of whom the Homeridae were an hereditary school. Wolf reached the conclusion that the Iliad and Odyssey could not have been composed in the form in which we know them without the aid of writing. They must therefore have been, as Bentley has said, a sequel of songs and rhapsodies, loose songs not collected together in the form of an epic poem until about 500 years after their original composition. This conclusion Wolf supports by the character attributed to the Cyclic poems (whose want of unity showed that the structure of the Iliad and Odyssey must be the work of a later time), by one or two indications of imperfect connection, and by the doubts of ancient critics as to the authenticity of certain parts.[8]

This view is extended by the complicating factor of the period of time now referred to as the "Greek Dark Ages". This period, which ranged from approximately 1100 to 750 BC, followed the Bronze Age period of Mycenaean Greece during which Homer's Trojan War is set. The composition of the Iliad, on the other hand, is placed immediately following the Greek Dark Age period.[citation needed]

Further controversy surrounds the difference in composition dates between the Iliad and Odyssey. It seems that the latter was composed at a later date than the former because the works' differing characterizations of the Phoenicians align with differing Greek popular opinion of the Phoenicians between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, when their skills began to hurt Greek commerce. Whereas Homer's description of Achilles's shield in the Iliad exhibits minutely detailed metalwork that characterized Phoenician crafts, they are characterized in the Odyssey as "manifold scurvy tricksters" (polypaipaloi, parodying the Greek polydaidaloi, "many-skilled").[19][20]

Identity of Homer

[edit]

Wolf's speculations were in harmony with the ideas and sentiment of the time, and his historical arguments, especially his long array of testimonies to the work of Peisistratus, were hardly challenged. The effect of Wolf's Prolegomena was so overwhelming, and its determination so decisive, that, although a few protests were made at the time, the true Homeric controversy did not begin until after his death in 1824.[8]

The first considerable antagonist of the Wolfian school was Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch, whose writings cover the years between 1828 and 1862 and deal with every side of the controversy. In the earlier part of his Metetemata (1830), Nitzsch took up the question of written or unwritten literature, on which Wolf's entire argument turned, and showed that the art of writing must be anterior to Peisistratus. In the later part of the same series of discussions (1837), and in his chief work (Die Sagenpoesie der Griechen, 1852), he investigated the structure of the Homeric poems, and their relation to the other epics of the Trojan cycle.[8]

These epics had in the meantime been made the subject of a work which, for exhaustive learning and delicacy of artistic perception, has few rivals in the history of philology: the Epic cycle of Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker. The confusion which previous scholars had made between the ancient post-Homeric poets (such as Arctinus of Miletus and Lesches) and the learned mythological writers (like the scriptor cyclicus of Horace) was first cleared up by Welcker. Wolf had argued that, had the cyclic writers known the Iliad and Odyssey which we possess, they would have imitated the unity of structure which distinguishes these two poems. The aim of Welcker's work was to show that the Homeric poems had influenced both the form and the substance of epic poetry.[8]

Thus arose a conservative school which admitted more or less freely the absorption of preexisting lays in the formation of the Iliad and Odyssey, and also the existence of considerable interpolations, but assigned the main work of formation to prehistoric times and the genius of a great poet.[21] Whether the two epics were by the same author remained an open question; the tendency of this group of scholars was towards separation. Regarding the use of writing, too, they were not unanimous. Karl Otfried Müller, for instance, maintained the view of Wolf on this point, while strenuously combating the inference which Wolf drew from it.[8]

The Prolegomena bore on the title-page the words "Volumen I", but no second volume ever appeared; nor was any attempt made by Wolf himself to compose it or carry his theory further. The first important steps in that direction were taken by Johann Gottfried Jakob Hermann, chiefly in two dissertations, De interpolationibus Homeri (Leipzig, 1832), and De iteratis apud Homerum (Leipzig, 1840), called forth by the writings of Nitzsch. As the word "interpolation" implies, Hermann did not maintain the hypothesis of a conflation of independent lays. Feeling the difficulty of supposing that all ancient minstrels sang of the wrath of Achilles or the return of Odysseus (leaving out even the capture of Troy itself), he was led to assume that two poems of no great compass, dealing with these two themes, became so famous at an early period as to throw other parts of the Trojan story into the background and were then enlarged by successive generations of rhapsodists. Some parts of the Iliad, moreover, seemed to him to be older than the poem on the wrath of Achilles; and thus, in addition to the Homeric and post-Homeric matter, he distinguished a pre-Homeric element.[8]

The conjectures of Hermann, in which the Wolfian theory found a modified and tentative application, were presently thrown into the shade by the more trenchant method of Karl Lachmann, who (in two papers read to the Berlin Academy in 1837 and 1841) sought to show that the Iliad was made up of sixteen independent lays, with various enlargements and interpolations, all finally reduced to order by Peisistratus. The first book, for instance, consists of a lay on the anger of Achilles (1–347), and two continuations, the return of Chryseis (430–492) and the scenes in Olympus (348–429, 493–611). The second book forms a second lay, but several passages, among them the speech of Odysseus (278–332), are interpolated. In the third book, the scenes in which Helen and Priam take part (including the making of the truce) are pronounced to be interpolations; and so on.[8]

New methods try also to elucidate the question. Combining information technologies and statistics, the stylometry allows to scan various linguistic units: words, parts of speech, and sounds. Based on the frequencies of Greek letters, a first study of Dietmar Najock[22] particularly shows the internal cohesion of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Taking into account the repetition of the letters, a recent study of Stephan Vonfelt[23] highlights the unity of the works of Homer compared to Hesiod. The thesis of modern analysts being questioned, the debate remains open.

Current status of the Homeric Question

[edit]Most scholars, although disagreeing on other questions about the genesis of the poems, agree that the Iliad and the Odyssey were not produced by the same author, based on "the many differences of narrative manner, theology, ethics, vocabulary, and geographical perspective, and by the apparently imitative character of certain passages of the Odyssey in relation to the Iliad."[24][25][26][27] Nearly all scholars agree that the Iliad and the Odyssey are unified poems, in that each poem shows a clear overall design, and that they are not merely strung together from unrelated songs.[27] It is also generally agreed that each poem was composed mostly by a single author, who probably relied heavily on older oral traditions.[27] Nearly all scholars agree that the Doloneia in Book X of the Iliad is not part of the original poem, but rather a later insertion by a different poet.[27]

Some ancient scholars believed Homer to have been an eyewitness to the Trojan War; others thought he had lived up to 500 years afterwards.[28] Contemporary scholars continue to debate the date of the poems.[29][30][27] A long history of oral transmission lies behind the composition of the poems, complicating the search for a precise date.[31] It is generally agreed, however, that the "date" of "Homer" should refer to the moment in history when the oral tradition became a written text.[32] At one extreme, Richard Janko has proposed a date for both poems to the eighth century BC based on linguistic analysis and statistics.[29][30] At the other extreme, scholars such as Gregory Nagy see "Homer" as a continually evolving tradition, which grew much more stable as the tradition progressed, but which did not fully cease to continue changing and evolving until as late as the middle of the second century BC.[29][30][27] Martin Litchfield West has argued that the Iliad echoes the poetry of Hesiod, and that it must have been composed around 660–650 BC at the earliest, with the Odyssey up to a generation later.[33][34][27] He also interprets passages in the Iliad as showing knowledge of historical events that occurred in the ancient Near East during the middle of the seventh century BC, including the destruction of Babylon by Sennacherib in 689 BC and the Sack of Thebes by Ashurbanipal in 663/4 BC.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kahane, p. 1.

- ^ Jensen, p. 10. This question has attracted luminaries from all walks of life, including William Ewart Gladstone, who amused himself in spare time by inditing a tome in dilation of the view that Homer was one man, solely and individually responsible for both the Iliad and the Odyssey.

- ^ Fowler, p. 23.

- ^ Luce, p. 15.

- ^ Nilsson, p. 11.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony. 1991. Defenders of the Text: The Traditions of Scholarship in an Age of Science, 1450–1800. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 225.

- ^ Gibson: Milman Parry.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Monro, David Binning; Allen, Thomas William (1911). "Homer". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 626–639. See especially p. 633 ff.

- ^ Lord: The Singer of Tales.

- ^ Kirk, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Foley, p. 35.

- ^ Foley, p. 62.

- ^ Foley, pp. 36, 505.

- ^ Parry, pp. 177–216.

- ^ Foley, pp. 40, 406.

- ^ Harris: Homer the Hostage.

- ^ Pseudo-Plutarch, De Homero

- ^ Graziosi, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Homer – Books and Biography. Martin Litchfield West in his 2010 commentary on the Iliad uses comparative evidence and the literary Shield of Achilles as one of many data that for him establish a composition date of 680–650.

- ^ "CAT Questionbank – Reading Comprehension Passage 4". iim-cat-questions-answers.2iim.com.

- ^ Caldecott, p. 1.

- ^ Najock Dietmar 1995, "Letter Distribution and Authorship in Early Greek Epics", Revue informatique et Statistique dans les Sciences Humaines, XXXI, 1 à 4, p. 129–154. Archived 5 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vonfelt Stephan, 2010, "Archéologie numérique de la poésie grecque", Université de Toulouse. Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ West, M.L. (1999). "The Invention of Homer". Classical Quarterly. 49 (2): 364–382. doi:10.1093/cq/49.2.364. JSTOR 639863.

- ^ West, Martin L. (2012). The Homeric Question - The Homer Encyclopedia. doi:10.1002/9781444350302.wbhe0605. ISBN 9781405177689.

- ^ Latacz, Joachim; Bierl, Anton; Olson, S. Douglas (2015). "New Trends in Homeric Scholarship" in Homer's Iliad: The Basel Commentary. De Gruyter. ISBN 9781614517375.

- ^ a b c d e f g h West, M. L. (December 2011). "The Homeric Question Today". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 155 (4). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society: 383–393. JSTOR 23208780.

- ^ Saïd, Suzanne (2011). Homer and the Odyssey. OUP Oxford. pp. 14–17. ISBN 9780199542840.

- ^ a b c Graziosi, Barbara (2002). Inventing Homer: The Early Reception of Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–92. ISBN 9780521809665.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Robert; Fowler, Robert Louis (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge University Press. pp. 220–232. ISBN 9780521012461.

- ^ Burgess, Jonathan S. (2003). The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle. JHU Press. pp. 49–53. ISBN 9780801874819.

- ^ Reece, Steve. "Homer's Iliad and Odyssey: From Oral Performance to Written Text," in Mark Amodio (ed.), New Directions in Oral Theory (Tempe: Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005) 43–89. Homers_Iliad_and_Odyssey_From_Oral_Performance_to_Written_Text. Reece, Steve. "Toward an Ethnopoetically Grounded Edition of Homer's Odyssey." Oral Tradition 26 (2011) 299–326.Toward_an_Ethnopoetically_Grounded_Edition_of_Homers_Odyssey

- ^ Hall, Jonathan M. (2002). Hellenicity: Between Ethnicity and Culture. University of Chicago Press. pp. 235–236. ISBN 9780226313290.

- ^ West, Martin L. (2012). "Date of Homer". The Homer Encyclopedia. doi:10.1002/9781444350302.wbhe0330. ISBN 9781405177689.

Works cited

[edit]- Homer – Books, Biography, Quotes – Read Print Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Caldecott, Harry Stratford (1896). Our English Homer; or, the Bacon-Shakespeare Controversy. Johannesburg Times.

- Foley, John M. (1985). Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography. Garland.

- Fowler, Harold North (1980) [1903]. A History of Ancient Greek Literature. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-096-8.

- Gibson, Twyla. "Milman Parry: The Oral-Formulaic Style of the Homeric Tradition". Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- Harris, William. "Homer the Hostage". Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- Graziosi, Barbara (2002). Inventing Homer: The Early Reception of Epic. Cambridge University Press.

- Jensen, Minna Skafte (1980). The Homeric Question and the Oral-Formulaic Theory. D. Appleton and Company.

- Kahane, Ahuvia (2005). Diachronic Dialogues: Authority and Continuity in Homer and the Homeric Tradition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7391-1134-5.

- Kirk, Geoffrey S. (1962). The Songs of Homer. Cambridge University Press.

- Lord, Albert (1960). The Singer of Tales. Harvard University Press.

- Luce, J.V. (1975). Homer and the Homeric Age. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-012722-0.

- Michalopoulos, Dimitris G (2016), Homer's Odyssey beyond the Myths, The Piraeus: Institute of Hellenic Maritime History, ISBN 978-618-80599-3-1

- Michalopoulos, Dimitris G. (2022), The Homeric Question Revisited. An Essay on the History of the Ancient Greeks, Washington DC-London: Academica Press, ISBN 978-168-05370-0-0

- Nilsson, Martin P. (1972). The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01951-5.

- Parry, Adam. "Have we Homer's Iliad?" Yale Classical Studies. 20 (1966), pp. 177–216.

- Varsos, Georges Jean, "The Persistence of the Homeric Question", Ph.D. thesis, University of Geneva, July 2002.

- West, Martin L. (2010). The Making of the Iliad. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199590070.