Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

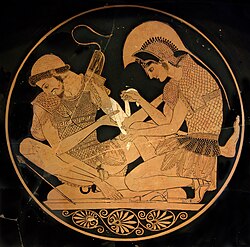

Euhemerism

View on Wikipedia| Trojan War |

|---|

|

In the fields of philosophy and mythography, euhemerism (/juːˈhiːmərɪzəm, -hɛm-/) is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exaggerated in the retelling, accumulating elaborations and alterations that reflect cultural mores. It was named after the Greek mythographer Euhemerus, who lived in the late 4th century BC. In the more recent literature of myth, such as Bulfinch's Mythology, euhemerism is termed the "historical theory" of mythology.[1]

Euhemerus was not the first to attempt to rationalize mythology in historical terms: euhemeristic views are found in earlier writings including those of Sanchuniathon, Xenophanes, Herodotus, Hecataeus of Abdera and Ephorus.[2][3] However, the enduring influence of Euhemerus upon later thinkers such as the classical poet Ennius (b. 239 BC) and modern author Antoine Banier (b. 1673 AD) identified him as the traditional founder of this school of thought.[4]

Early history

[edit]In a scene described in Plato's Phaedrus, Socrates offers a euhemeristic interpretation of a myth concerning Boreas and Orithyia:

Phaedr. On the way to the Ilissus Phaedrus asks the opinion of Socrates respecting the truth of a local legend.

I should like to know, Socrates, whether the place is not somewhere here at which Boreas is said to have carried off Orithyia from the banks of the Ilissus?

Soc. Such is the tradition.

Phaedr. And is this the exact spot? The little stream is delightfully clear and bright; I can fancy that there might be maidens playing near.

Soc. I believe that the spot is not exactly here, but about a quarter of a mile lower down, where you cross to the temple of Artemis, and there is, I think, some sort of an altar of Boreas at the place.

Phaedr. I have never noticed it; but I beseech you to tell me, Socrates, do you believe this tale?

Soc. Socrates desires to know himself before he enquires into the newly found philosophy of mythology.

The wise are doubtful, and I should not be singular if, like them, I too doubted. I might have a rational explanation that Orithyia was playing with Pharmacia, when a northern gust carried her over the neighbouring rocks; and this being the manner of her death, she was said to have been carried away by Boreas.[5]

Socrates illustrates a euhemeristic approach to the myth of Boreas abducting Orithyia. He shows how the story of Boreas, the northern wind, can be rationalised: Orithyia is pushed off the rock cliffs through the equation of Boreas with a natural gust of wind, which accepts Orithyia as a historical personage. But here he also implies that this is equivalent to rejecting the myth. Socrates, despite holding some euhemeristic views, mocked the concept that all myths could be rationalized, noting that the mythical creatures of "absurd forms" such as Centaurs and the Chimera could not easily be explained.[6]

In the ancient skeptic philosophical tradition of Theodorus of Cyrene and the Cyrenaics, Euhemerus forged a new method of interpretation for the contemporary religious beliefs. Though his work is lost, the reputation of Euhemerus was that he believed that much of Greek mythology could be interpreted as natural or historical events subsequently given supernatural characteristics through retelling. Subsequently, Euhemerus was considered to be an atheist by his opponents, most notably Callimachus.[7]

Deification

[edit]Euhemerus's views were rooted in the deification of men, usually kings, into gods through apotheosis. In numerous cultures, kings were exalted or venerated into the status of divine beings and worshipped after their death, or sometimes even while they ruled. Dion, the tyrant ruler of Syracuse, was deified while he was alive and modern scholars consider his apotheosis to have influenced Euhemerus' views on the origin of all gods.[8] Euhemerus was also living during the contemporaneous deification of the Seleucids and "pharaoization" of the Ptolemies in a fusion of Hellenic and Egyptian traditions.

Tomb of Zeus

[edit]Euhemerus argued that Zeus was a mortal king who died on Crete, and that his tomb could still be found there with the inscription bearing his name.[9] This claim however did not originate with Euhemerus, as the general sentiment of Crete during the time of Epimenides of Knossos (c. 600 BC) was that Zeus was buried somewhere in Crete. For this reason, the Cretans were often considered atheists, and Epimenides called them all liars (see Epimenides paradox). Callimachus, an opponent of Euhemerus's views on mythology, argued that Zeus's Cretan tomb was fabricated, and that he was eternal:

Cretans always lie. For the Cretans even built a tomb,

Lord, for you. But you did not die, for you are eternal.[10]

A later Latin scholium on the Hymns of Callimachus attempted to account for the tomb of Zeus. According to the scholium, the original tomb inscription read: "The tomb of Minos, the son of Jupiter" but over time the words "Minos, the son" wore away leaving only "the tomb of Jupiter". This had misled the Cretans into thinking that Zeus had died and was buried there.[11]

Influenced by Euhemerus, Porphyry in the 3rd century AD claimed that Pythagoras had discovered the tomb of Zeus on Crete and written on the tomb's surface an inscription reading: "Here died and was buried Zan, whom they call Zeus".[12] Varro also wrote about the tomb of Zeus.

Christianity

[edit]Hostile to paganism, the early Christians, such as the Church Fathers, embraced euhemerism in attempt to undermine the validity of pagan gods.[13] The usefulness of euhemerist views to early Christian apologists may be summed up in Clement of Alexandria's triumphant cry in Cohortatio ad gentes: "Those to whom you bow were once men like yourselves."[14]

The Book of Wisdom

[edit]The Wisdom of Solomon, a deuterocanonical book, has a passage giving a euhemerist explanation of the origin of idols.[15]

Early Christian apologists

[edit]The early Christian apologists deployed the euhemerist argument to support their position that pagan mythology was merely an aggregate of fables of human invention. Cyprian, a North African convert to Christianity, wrote a short essay De idolorum vanitate ("On the Vanity of Idols") in 247 AD that assumes the euhemeristic rationale as though it needed no demonstration. Cyprian begins:

That those are no gods whom the common people worship, is known from this: they were formerly kings, who on account of their royal memory subsequently began to be adored by their people even in death. Thence temples were founded to them; thence images were sculptured to retain the countenances of the deceased by the likeness; and men sacrificed victims, and celebrated festal days, by way of giving them honour. Thence to posterity those rites became sacred, which at first had been adopted as a consolation.

Cyprian proceeds directly to examples, the apotheosis of Melicertes and Leucothea; "The Castors [i.e. Castor and Pollux] die by turns, that they may live", a reference to the daily sharing back and forth of their immortality by the Heavenly Twins. "The cave of Jupiter is to be seen in Crete, and his sepulchre is shown", Cyprian says, confounding Zeus and Dionysus but showing that the Minoan cave cult was still alive in Crete in the third century AD. In his exposition, it is to Cyprian's argument to marginalize the syncretism of pagan belief, in order to emphasize the individual variety of local deities:

From this the religion of the gods is variously changed among individual nations and provinces, inasmuch as no one god is worshipped by all, but by each one the worship of its own ancestors is kept peculiar.

Eusebius in his Chronicle employed euhemerism to argue the Babylonian God Baʿal was a deified ruler and that the god Belus was the first Assyrian king.[16]

Euhemeristic views are found expressed also in Tertullian (De idololatria), the Octavius of Marcus Minucius Felix and in Origen.[17] Arnobius' dismissal of paganism in the fifth century, on rationalizing grounds, may have depended on a reading of Cyprian, with the details enormously expanded. Isidore of Seville, compiler of the most influential early medieval encyclopedia, devoted a chapter De diis gentium[18] to elucidating, with numerous examples and elaborated genealogies of gods, the principle drawn from Lactantius, Quos pagani deos asserunt, homines olim fuisse produntur ("Those whom pagans claim to be gods were once mere men"). Elaborating logically, he attempted to place these deified men in the six great periods of history as he divided it, and created mythological dynasties. Isidore's euhemeristic bent was codified in a rigid parallel with sacred history in Petrus Comestor's appendix to his much translated Historia scholastica (written c. 1160), further condensing Isidore to provide strict parallels of figures from the pagan legend, as it was now viewed in historicised narrative, and the mighty human spirits of the patriarchs of the Old Testament.[19] Martin of Braga, in his De correctione rusticorum, wrote that idolatry stemmed from post-deluge survivors of Noah's family, who began to worship the sun and stars instead of God. In his view, the Greek gods were deified descendants of Noah who were once real personages.[20]

Middle Ages

[edit]Christian writers during the Middle Ages continued to embrace euhemerism, such as Vincent of Beauvais, Petrus Comestor, Roger Bacon and Godfrey of Viterbo.[21][22] According to John Daniel Cooke, medieval Christian scholars embraced euhemerism because they believed that:

While in most respects the ancient Greeks and Roman had been superior to themselves, they had been in error regarding their religious beliefs. An examination of the principal writings in Middle English with considerable reading of literature other than English, discloses the fact that the people of the Middle Ages rarely regarded the so-called gods as mere figments of the imagination but rather believed that they were or had been real beings, sometimes possessing actual power.[21]

Other scholars have written that:

It was during this time that Christian apologists had adopted the views of the rationalist Greek philosophers. And had captured the purpose for Euhemerism, which was to explain the mundane origins of the Hellenistic divinities. Euhemerism explained simply in two ways: first in the strictest sense as a movement which reflected the known views of Euhemerus' Hiera Anagraphe regarding Panchaia and the historicity of the family of Saturn and Uranus. The principal sources of these views are the handed-down accounts of Lactantius and Diodorus; or second, in the widest sense, as a rationalist movement which sought to explain the mundane origins of all the Hellenistic gods and heroes as mortals.[This quote needs a citation]

Snorri Sturluson's "euhemerism"

[edit]In the Prose Edda, composed around 1220, the Christian Icelandic bard and historian Snorri Sturluson proposes that the Norse gods were originally historical leaders and kings. Odin, the father of the gods, is introduced as a historical person originally from Asia Minor, tracing his ancestry back to Priam, the king of Troy during the Trojan War.[23][24]

As Odin travels north to settle in the Nordic countries, he establishes the royal families ruling in Denmark, Sweden and Norway at the time:

And whatever countries they passed through, great glory was spoken of them, so that they seemed more like gods than men.[25]

Snorri's euhemerism follows the early Christian tradition.[citation needed]

In the modern world

[edit]Euhemeristic interpretations of mythology continued throughout the early modern period from the 16th century,[26] to modern times. In 1711, the French historian Antoine Banier in his Mythologie et la fable expliqués par l'histoire ("The Mythology and Fables of the Ancients, Explained") presented strong arguments for a euhemerist interpretation of Greek mythology.[27] Jacob Bryant's A New System or Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1744) was also another key work on euhemerism of the period, but argued so from a Biblical basis. Of the early 19th century, George Stanley Faber was another Biblical euhemerist. His work The Origin of Pagan Idolatry (1816) proposed that all the pagan nations worshipped the same gods, who were all deified men. Outside of Biblical influenced literature, some archaeologists embraced euhemerist views since they discovered myths could verify archaeological findings. Heinrich Schliemann was a prominent archaeologist of the 19th century who argued myths had historical truths embedded in them. Schliemann was an advocate of the historical reality of places and characters mentioned in the works of Homer. He excavated Troy and claimed to have discovered artifacts associated with various figures from Greek mythology, including the Mask of Agamemnon and Priam's Treasure.

Herbert Spencer embraced some euhemeristic arguments in attempt to explain the anthropocentric origin of religion, through ancestor worship. Rationalizing methods of interpretation that treat some myths as traditional accounts based upon historical events are a continuous feature of some modern readings of mythology.

The twentieth century poet and mythographer Robert Graves offered many such "euhemerist" interpretations in his telling of The White Goddess (1948) and The Greek Myths (1955). His suggestions that such myths record and justify the political and religious overthrow of earlier cult systems have been widely criticized and are rejected by most scholars.[28][excessive citations]

Euhemerization

[edit]Author Richard Carrier defines "euhemerization" as "the taking of a cosmic god and placing him at a definite point in history as an actual person who was later deified".

Euhemerus ... depicted an imaginary scholar discovering that Zeus and Uranus were once actual kings. In the process Euhemerus invents a history for these 'god kings', even though we know there is no plausible case to be made that either Zeus or Uranus was ever a real person.[29]

In this framing, rather than being presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages, the mythological accounts are claimed to have had such origins, and historical accounts invented accordingly – such that, counter to the usual sense of "Euhemerism", in "euhemerization" a mythological figure is in fact transformed into a (pseudo)historical one.

See also

[edit]- Demythologization

- Geomythology

- Legendary progenitor

- Transmission chain method

- Shaggy God story – Sub-genre in science fiction

References

[edit]- ^ Bulfinch, Thomas. Bulfinch's Mythology. Whitefish: Kessinger, 2004, p. 194.

- ^ S. Spyridakis: "Zeus Is Dead: Euhemerus and Crete" The Classical Journal 63.8 (May 1968, pp. 337–340) p.338.

- ^ Herodotus presented rationalized accounts of the myth of Io (Histories I.1ff) and events of the Trojan War (Histories 2.118ff).

- ^ An introduction to mythology, Lewis Spence, 1921, p. 42.

- ^ Jowett, Benjamin (1892). . pp. Plato, Phaedr. 229b–d – via Wikisource.

- ^ Phaedrus, 229d

- ^ S. Spyridakis, 1968, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Franco De Angelis and Benjamin Garstad, "Euhemerus in Context", Classical Antiquity, Vol. 25, No. 2, October 2006, pp. 211–242.

- ^ Zeus Is Dead: Euhemerus and Crete, S. Spyridakis, The Classical Journal, Vol. 63, No. 8, May, 1968, pp. 337–340.

- ^ Callimachus, Hymn to Zeus

- ^ The hymns of Callimachus, tr. into Engl. verse, with notes. To which are added, Select epigrams, and the Coma Berenices of the same author, six hymns of Orpheus, and the Encomium of Ptolemy by Theocritus, by W. Dodd, 1755, p. 3, footnote.

- ^ Epilegomena to the Study of Greek Religions and Themis a Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, Jane Ellen Harrison, Kessinger Publishing, 2003, p. 57.

- ^ "Euhemerism: A Mediaeval Interpretation of Classical Paganism", John Daniel Cooke, Speculum, Vol. 2, No. 4, October 1927, p. 397.

- ^ Quoted in Seznec (1995), The Survival of the Pagan Gods, Princeton University Press, p. 12, who observes (p. 13) of the numerous Christian examples he mentions, "Thus Euhemerism became a favorite weapon of the Christian polemicists, a weapon they made use of at every turn".

- ^ Wisdom 14:12–21

- ^ Chronicon, Pat. Graeca XIX, cols. 132, 133, i. 3.

- ^ Euhemerism and Christology in Origen: "Contra Celsum" III 22–43, Harry Y. Gamble, Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 33, No. 1, March 1979, pp. 12–29.

- ^ Isidore, Etymologiae, book viii, ch. 12.

- ^ Seznec 1995:16.

- ^ "Chapter 4: Pagan Survivals in Galicia in the Sixth Century".

- ^ a b John Daniel Cooke, "Euhemerism: A Mediaeval Interpretation of Classical Paganism", Speculum, Vol. 2, No. 4, October 1927, pp. 396–410.

- ^ The Franciscan friar Roger Bacon in the 13th century argued that ancient Gods such as Minerva, Prometheus, Atlas, Apollo, Io and Mercury were all deified humans. Opus Maius, ed. J. H. Bridges, Oxford, 1897, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Brouwers, Josho (2021-05-20). "Did Odin come from Troy? - The Anatolian origins of the Norse pantheon". Ancient World Magazine. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ Rix, Robert (2010). "Oriental Odin: Tracing the east in northern culture and literature". History of European Ideas. 36 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1016/j.histeuroideas.2009.10.006.

- ^ Snorri Sturluson, trans. Anthony Faulkes, Edda. Everyman. 1987. (Prologue, p. 4)

- ^ For example, in the preface to Arthur Golding's 1567 translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses into English, Golding offers a rationale for contemporary Christian readers to interpret Ovid's pagan stories. He argues: "The true and everliving God the Paynims did not know: Which caused them the name of Gods on creatures to bestow".

- ^ The Rise of Modern Mythology, 1680–1860, Burton Feldman, Robert D. Richardson, Indiana University Press, 2000, p. 86.

- ^

- Wood, Juliette (1999). "Chapter 1: The Concept of the Goddess". In Sandra Billington; Miranda Green (eds.). The Concept of the Goddess. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9780415197892. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 320. ISBN 9780631189466.

- The Paganism Reader. p. 128.

- Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 145. ISBN 9780631189466.

- Lewis, James R. Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft. p. 172.

- G. S. Kirk, Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures, Cambridge University Press, 1970, p. 5. ISBN 0-520-02389-7

- Richard G. A. Buxton, Imaginary Greece: The Contexts of Mythology, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 5. ISBN 0-521-33865-4

- Mary Lefkowitz, Greek Gods, Human Lives

- Kevin Herbert, "Review of The Greek Myths", The Classical Journal, Vol. 51, No. 4. (January 1956), pp. 191–192.

- ^ Carrier, Richard (2014). On the Historicity of Jesus. Sheffield Phoenix Press. p. 222. ISBN 9781909697355.