Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

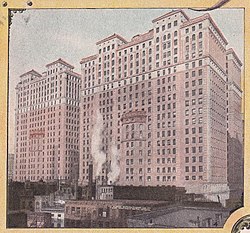

Hudson Terminal

View on Wikipedia

Hudson Terminal was a rapid transit station and office-tower complex in the Radio Row neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Opened during 1908 and 1909, it was composed of a terminal station for the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M), as well as two 22-story office skyscrapers and three basement stories. The complex occupied much of a two-block site bounded by Greenwich, Cortlandt, Church, and Fulton Streets, which later became the World Trade Center site.

Key Information

The railroad terminal contained five tracks and six platforms serving H&M trains to and from New Jersey; these trains traveled via the Downtown Hudson Tubes, under the Hudson River, to the west. The two 22-story office skyscrapers above the terminal, the Fulton Building to the north and the Cortlandt Building to the south, were designed by architect James Hollis Wells of the firm Clinton and Russell in the Romanesque Revival style. The basements contained facilities such as a shopping concourse, an electrical substation, and baggage areas. The complex could accommodate 687,000 people per day, more than Pennsylvania Station in Midtown Manhattan.

The buildings opened first, being the world's largest office buildings upon their completion, and the terminal station opened afterward. The H&M was successful until the mid-20th century, when it went bankrupt. The railroad and Hudson Terminal were acquired in 1962 by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which rebranded the railroad as Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH). The Port Authority agreed to demolish Hudson Terminal to make way for the World Trade Center, and the railroad station closed in 1971, being replaced by PATH's World Trade Center station. While the buildings were demolished in 1972, the last remnants of the station were removed in the 2000s as part of the development of the new World Trade Center following the September 11 attacks in 2001.

History

[edit]Planning and construction

[edit]In January 1905, the Hudson Companies was incorporated for the purpose of completing the Uptown Hudson Tubes, a tunnel between Jersey City, New Jersey, and Midtown Manhattan, New York City, that had been under construction intermittently since 1874. The Hudson Companies would also build the Downtown Hudson Tubes, which included a station in Jersey City's Exchange Place neighborhood, as well as a terminal station and a pair of office buildings in Lower Manhattan, which would become Hudson Terminal.[1][2] Following the announcement of the Downtown Tubes, the rate of real estate purchases increased around Hudson Terminal's future location.[3]

The Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company was incorporated in December 1906 to operate the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M), a passenger railroad system headed by William Gibbs McAdoo, which would use the tubes.[4][5] The system connected Hoboken, Pavonia, and Exchange Place, three of the five major railroad terminals on the western shore of the Hudson River waterfront.[6][7][a] At the time, there was high passenger traffic between New Jersey and Lower Manhattan. Passenger and mass-transit traffic in Jersey City was concentrated around the neighborhood of Exchange Place, while traffic in Lower Manhattan was centered south of New York City Hall. In addition, low construction costs and low property values were considerations in selecting the location of the railroad's Lower Manhattan terminal. The H&M only searched for sites west of Broadway, since there were more transit connections and fewer existing buildings west of that street.[9]

Land acquisition for the buildings started in December 1905. The Hudson Companies acquired most of the two blocks bounded by Greenwich Street to the west, Cortlandt Street to the south, Church Street to the east, and Fulton Street to the north. Some low-rise buildings on Cortlandt Street were acquired to protect the views from the Hudson Terminal buildings.[10] One landowner—the Wendel family, which owned a myriad of Manhattan properties—refused to sell their property, assessed at $75,000 (equivalent to $2,023,871 in 2024[b]), and filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against H&M in which they spent $20,000 (equivalent to $539,699 in 2024[b]) on legal fees.[11][12] By May 1906, H&M had taken title to most of the land.[13] The 70,000 square feet (6,500 m2) acquired for the complex[14] had cost an average of $40 to $45 per square foot ($430 to $480/m2).[15][16] The New York Times predicted that the development of Hudson Terminal would result in the relocation of many manufacturing plants from New Jersey to Lower Manhattan.[17]

Excavations at the site of the office buildings were underway by early 1907,[18] and the first columns for the substructure were placed in May 1907.[13][19] Because of the presence of wet soil in the area, and the proximity of the Hudson River immediately to the west, a cofferdam was built around the site of the Hudson Terminal buildings.[20][21] According to architectural writers Sarah Landau and Carl W. Condit, the cofferdam was five times larger than any such structure previously constructed.[20] At the time, there was a lot of office space being developed in Lower Manhattan, even as the area saw a decrease in real-estate transactions.[22] The project was completed for $8 million (equivalent to $196 million in 2024[b]).[20] The buildings were owned by the H&M Railroad upon their completion.[23]

Opening and usage

[edit]

By April 4, 1908, tenants started moving into the towers.[13][14][19] Originally, the northern office building was called the Fulton Building while the southern office building was called the Cortlandt Building, reflecting the streets that they abutted.[24] The H&M terminal opened on July 19, 1909,[25][26] along with the Downtown Tubes.[21][25] The combined rail terminal and office block was the first of its kind anywhere in the world.[27][c]

The space in the office buildings was in high demand, and the offices were almost fully rented by 1911.[29] The following year, McAdoo denied rumors that H&M would acquire the low-rise buildings on Greenwich Street to expand the Hudson Terminal buildings.[30] Upon the tubes' opening, they were also popular with New Jersey residents who wanted to travel to New York City.[25] Passenger volume at Hudson Terminal had reached 30,535,500 annually by 1914,[31] and within eight years, nearly doubled to 59,221,354.[32] Several modifications were made to the complex in the years after its completion. Smaller annexes were added to the office buildings at some point after they opened, during the early or mid-20th century.[33]

A passageway to the Independent Subway System (IND)'s Chambers Street station was opened in 1949.[34][35] The passageway measured 14 feet (4.3 m) wide and 90 feet (27 m) long. Construction contractor Great Atlantic Construction Company described the tunnel as "one of the most difficult of engineering feats", as the passageway had to pass above the H&M tunnels while avoiding various pipes, wires, water mains, and cable car lines.[35]

Early tenants of the Hudson Terminal buildings included companies in the railroad industry;[36][37] the offices of U.S. Steel;[37][38] and some departments of New York City's general post office, which had been crowded out of its older building.[37][39] U.S. Steel, the post office, and six railroad companies occupied 309,000 square feet (28,700 m2), or over a third of the total space in the buildings.[37] The top floors of each building had private dining clubs: the Downtown Millionaires Club atop the Cortlandt Building and the Machinery Club atop the Fulton Building.[20][38] With the exception of a brief period between 1922 and 1923,[40] the terminal's post office operated until the United States Postal Annex at 90 Church Street opened two blocks north in 1937.[41] Space in the buildings was also occupied by agencies of the United States federal government in the 1960s.[42]

Decline and demolition

[edit]H&M ridership declined substantially from a high of 113 million riders in 1927 to 26 million in 1958, after new automobile tunnels and bridges opened across the Hudson River.[43] The H&M had gone bankrupt in 1954.[44] The state of New Jersey wanted the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to take over the railroad, but the Port Authority had long viewed it as unprofitable.[45] In 1958, the investment firm Koeppel & Koeppel offered to buy the terminal buildings for $15 million (equivalent to $125 million in 2024[b]), as part of a reorganization hearing for the H&M.[46]

The Port Authority ultimately took over the H&M as part of an agreement concerning the construction of the World Trade Center.[45] The Port Authority had initially proposed constructing the complex on the East River, on the opposite side of Lower Manhattan from Hudson Terminal.[47][48] As an interstate agency, the Port Authority required approval for its projects from both New Jersey's and New York's state governments, but the New Jersey government objected that the proposed trade center would mostly benefit New York.[45] In late 1961, Port Authority executive director Austin J. Tobin proposed shifting the project to Hudson Terminal and taking over the H&M in exchange for New Jersey's agreement.[49] On January 22, 1962, the two states reached an agreement to allow the Port Authority to take over the railroad, rebrand it as the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH), and build the World Trade Center on the Hudson Terminal site, which was by then deemed obsolete.[50] The World Trade Center project would include a new PATH station to replace the Hudson Terminal station, as well as a public plaza to replace the buildings.[51]

Groundbreaking on the World Trade Center took place in 1966,[52] and as with the Hudson Terminal buildings, a slurry wall to keep out water from the Hudson River. During excavation of the site and construction of the towers, the Downtown Tubes remained in service, with excavations continuing around and below the tunnels.[53] The Hudson Terminal station closed on July 2, 1971, to allow a three-day maintenance period to divert service to its replacement, the original World Trade Center PATH station.[54] The World Trade Center station opened on July 6, 1971, west of the Hudson Terminal station.[55] Just before the buildings' demolition, in early 1972, the New York City Fire Department used the empty Cortlandt Building for several fire safety tests, setting fires to collect data for fire safety.[56][57] The Hudson Terminal complex was demolished by the end of 1972.[58]

After the World Trade Center station opened, the sections of the Downtown Tubes between the Hudson Terminal and World Trade Center stations were taken out of service and turned into loading docks for the 4 World Trade Center and 5 World Trade Center buildings on Church Street.[59] The original PATH station was destroyed in 2001 during the September 11 attacks.[60] The last remnant of the Hudson Terminal station was a cast-iron tube embedded in the original World Trade Center's foundation near Church Street. The tube was above the level of the PATH station and the station's replacement after the September 11 attacks. The cast-iron tube was removed in 2008 during the construction of the new World Trade Center.[61]

Railroad station

[edit]The terminal served H&M trains as well as those of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which interoperated on H&M trackage.[21][62] The railroad terminal's construction was overseen by Charles H. Jacobs, chief engineer, and J. Vipond Davies, deputy chief engineer.[63][64][65] The terminal was two stories below street level and consisted of five tracks numbered 1–5 from east to west. The tracks were served by four island platforms and two side platforms.[59][66] All tracks had a Spanish solution layout with platforms on both sides, thereby enabling passengers to exit trains from one side and enter from the other.[67][68][69][9] This removed conflicts between departing and boarding passengers.[9] The width of the station averaged 180 feet (55 m) from west to east, and the station measured 530 feet (160 m) long from north to south.[16]

Lower Manhattan's topography made it impossible for the H&M to build a "stub-end" terminal, with the tracks oriented on a west–east axis and terminating at bumper blocks.[9] Therefore, the Hudson Terminal station was arranged as a balloon loop connecting both of the Downtown Tubes.[9][70] Trains entered from the south and exited from the north.[70] The station ran perpendicularly to both of the Downtown Tubes, and at either end of the station, there were sharp curves to and from each tube, with track radii of 90 feet (27 m). The eastbound tunnel ran under Cortlandt Street and the westbound tunnel ran two blocks north under Fulton Street.[68]

Platforms and tracks

[edit]Track layout | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Map is not to scale. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The station had been built with five tracks because, at the time of its construction, there were plans to build another pair of tunnels under the Hudson River near the Downtown Tubes. The H&M anticipated that two terminal tracks would be needed for each pair of tunnels; the fifth track was needed for flexibility.[9][21][71] The additional tunnels were ultimately never built, and several subway tunnels were built very close to the Hudson Terminal complex.[21] Track 5, the westernmost track, was used by baggage trains and was designated as the "emergency" track. The westernmost side platform, serving Track 5, was used for handling baggage, delivering coal, and depositing ashes from the buildings' power station.[68][71] The easternmost side platform adjacent to track 1, as well as the island platforms between tracks 2/3 and 4/5, were used by alighting passengers only. The island platforms between tracks 1/2 and 3/4 were used by boarding passengers.[68][71] The station was designed to accommodate a full trainload of 800 passengers every 90 seconds, the maximum capacity of the Downtown Tubes.[72]

Each of the platforms were 370 feet (110 m) long and could fit trains of eight 48.5-foot-long (14.8 m) cars.[26][73][74] The platform widths were determined by the projected passenger loads for each track; the boarding platforms were wider than the alighting platforms and at least twice the width of the trains. The eastern side platform was 11.5 feet (3.5 m) wide because it was used only by alighting passengers from track 1, and the island platform for alighting passengers between tracks 4/5 was 13 feet (4.0 m) wide because track 5 was not used in regular service. The other three island platforms were 22 feet (6.7 m) wide because they each served two tracks that were used in regular passenger service.[16][72] The engineers studied pedestrian traffic at the Brooklyn Bridge and other congested areas to determine the design of the station's ramps and staircases. There were six stairs from each alighting platform and four stairs to each boarding platform.[75]

Except at the platforms' extreme ends, the platforms contained straight edges to minimize the gap between train and platform.[26][73][76] The straight section of each platform was 350 feet (110 m) long.[9] Other stations on loops—including the City Hall and South Ferry stations of the New York City Subway, built by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)—contained curved platforms, whose gaps between platform and train posed a great liability to passenger safety.[77] Illuminated departure signs on each platform displayed the destinations of the trains on each track. The station was lit by incandescent lamps throughout.[76]

Surrounding infrastructure

[edit]The station tunnels contained provisions for an unbuilt extension northward to what is now the 34th Street–Herald Square station on the New York City Subway.[78][79] If this extension had been built, it would have tripled the maximum number of trains that could go into the Hudson Terminal station.[78] The sections of tunnel around the Hudson Terminal station were taken out of regular service when the World Trade Center station was built about 450 feet (140 m) to the west.[59] The World Trade Center station could fit ten-car trains, and sat underneath Greenwich Street, which was oriented further northwestward compared to the Hudson Terminal station parallel to Church Street.[80] Because it was longer than the Hudson Terminal station, a large jughandle curve was built from either tube to the World Trade Center station, surrounding the Hudson Terminal approach tracks.[77][80] The sections of the tubes east of Greenwich Street were subsequently turned into loading docks serving 4 and 5 World Trade Center.[59]

To the north and south of the station, each end of the loop had a loading gauge large enough to fit one train.[70] The cars required a clearance of 12 feet 6 inches (3.81 m) above the tops of the rails, while the floor of the tunnel was 24 inches (610 mm) below the tops of the rails.[16] The single tubes of the Downtown Tubes enabled better ventilation of the station by the so-called piston effect. When a train passed through the tunnel, it pushed out the air in front of it toward the closest ventilation shaft, and also pulled air into the rail tunnel from the closest ventilation shaft behind it.[63][81] The Hudson Terminal station also used fans to accelerate the movement of air.[63]

Connections

[edit]When the Hudson Terminal buildings opened, direct transfers were available to the IRT's Sixth Avenue elevated at Cortlandt and Church Streets, and to the Ninth Avenue elevated at Cortlandt and Greenwich Streets.[26] The connection to the Sixth Avenue Line station, opened in September 1908, was via an elevated passageway from the third floor of the Cortlandt Building.[23] In 1932, the Independent Subway System opened the Hudson Terminal station on its Eighth Avenue Line, though the IND station was operationally separate from the H&M station.[82] Though the IND had also planned for a passageway between its Chambers Street station and the H&M's terminal in the original plan for the Eighth Avenue Line, a direct passageway to the Chambers Street station was not opened until 1949.[34]

Towers

[edit]

Hudson Terminal included two 22-story Romanesque-style office skyscrapers above the H&M station.[14][83] The buildings were designed by architect James Hollis Wells, of the firm Clinton and Russell, and built by construction contractor George A. Fuller.[14][24][65] Purdy and Henderson were retained as the structural engineers.[64][65] Located on what would later become the World Trade Center site, the Hudson Terminal buildings preceded the original World Trade Center complex in both size and function.[27] When the Hudson Terminal buildings opened, the height and design of skyscrapers was still heavily debated, and New York City skyscrapers were criticized for their bulk and density. Some of the city's early-20th-century skyscrapers were thus designed with towers, campaniles, or domes above a bulky base, while others were divided into two structures, as at Hudson Terminal.[84] Furthermore, high real-estate costs made it impractical to build "anything but an office building" above the terminal.[85]

The buildings occupied most of the site bounded by Cortlandt Street to the south, Church Street to the east, and Fulton Street to the west, with the northern building at 50 Church Street and the southern building at 30 Church Street. The site was also abutted by several low-rise buildings on Greenwich Street to the west.[27] They were respectively called the Fulton Building and the Cortlandt Building, and were also collectively referred to as the Church Street Terminal.[24][86] The buildings were separated by Dey Street, since the city government would not allow the street to be closed and eliminated.[14][87]

Form

[edit]The Hudson Terminal buildings, along with 49 Chambers, were the city's first skyscrapers to include an H-shaped floor plan, with interior "light courts" to provide illumination to interior offices.[88] The buildings' land lots originally occupied a combined 70,000 square feet (6,500 m2).[14] According to the Engineering Record, the Fulton Building occupied a lot measuring about 156 by 154 feet (48 by 47 m), while the Cortlandt Building occupied a lot measuring about 213 by 170 feet (65 by 52 m).[89] However, the New-York Tribune gave slightly different measurements of 155.9 by 179.8 feet (48 by 55 m) for the Fulton Building and 214.35 by 186.3 feet (65 by 57 m) for the Cortlandt Building.[24] By the mid-20th century, annexes had been added to both buildings, giving them a combined lot area of 85,802 square feet (7,971.3 m2).[33]

The two buildings were otherwise designed similarly. The first through third stories of both buildings were parallelogram in plan, while the buildings contained H-shaped floor plans above the third story. The light courts of both buildings faced north and south, while the main corridors of each level on both buildings extended eastward from Church Street.[90][91] The Cortlandt Building's light courts measured 32 by 76 feet (9.8 by 23.2 m), while the Fulton Building's light courts were 48 by 32 feet (14.6 by 9.8 m). The wings on either side of the light courts were of asymmetrical width.[89] The main roofs of the buildings were carried to 275.75 feet (84.05 m) above ground.[24][89] Small projecting "towers" with pitched roofs rose from the Church Street side of both buildings, rising to 304 feet (93 m).[20][89]

Facade

[edit]The designs for the buildings' facades called for Indiana limestone cladding below the fifth-floor cornice, and brick and terracotta above.[24][73][83][89] The original proposal included rows of triple-height Doric columns supporting the roof cornice.[24] As built, the lowest four stories of each building were made of polished granite and limestone; each ground level bay was filled with glass. The top six stories of each building contained light-toned terracotta, as in the original plan.[20][73] The corners of each building had light terracotta strips as well. Tall arches connected three of the top six stories.[20] Because of the differing dimensions of the buildings, the Fulton Building had eighteen bays facing Church Street and nineteen facing Dey Street, while the Cortlandt Building had twenty-two bays facing Church Street and twenty facing Cortlandt Street.[24]

The two buildings were connected by a pedestrian bridge over the street on the third story of each building.[78] A bridge connecting the buildings' 17th floors was approved and built in 1913, soon after the complex had opened.[92][93]

Features

[edit]As completed, the buildings used 16.3 million bricks, 13,000 lighting fixtures, 15,200 doors, 5,000 windows, and 4,500 short tons (4,000 long tons; 4,100 t) of terracotta, as well as 1,300,000 square feet (120,000 m2) of partitions and 1,100,000 cubic feet (31,000 m3) of concrete floor arches. Also included in the buildings were many miles of plumbing, steam piping, wood base, picture molding, conduits, and electrical wiring.[63]

Structural features

[edit]

The superstructure of the Hudson Terminal buildings required over 28,000 short tons (25,000 long tons; 25,000 t) of steel, manufactured by the American Bridge Company.[87][89] The superstructure of the Fulton Building was intended to carry a dead load of 95 pounds per square foot (4.5 kPa) and a live load of 105 psf (5.0 kPa), for 200 psf (9.6 kPa) total, while the Cortlandt Building could carry a dead load of 85 psf (4.1 kPa) and a live load of 75 psf (3.6 kPa), for 160 psf (7.7 kPa) total.[89] The columns were allowed to take a minimum stress of 11,500 psi (79,000 kPa) and a maximum stress of 13,000 psi (90,000 kPa).[64][89]

The floors were generally made of reinforced concrete slabs placed between I-beams, with cinder concrete fill and yellow-pine finish. Terracotta tile, brick, and concrete was used to encase the structural steel frame.[89] The I-beams were supported by columns or on plate girders. Large wind braces were not used; instead, the flanges of the beams and girders were riveted to the columns with what the Engineering Record described as "a moment of stiffness equal or somewhat superior to the depth of the girder".[94]

Interior

[edit]The towers had a combined 39 elevators, which could carry 30,000 people a day. This included 17 passenger elevators and a freight elevator in the Fulton Building, and 21 elevators in the Cortlandt Building. Of the 39 elevators in the buildings, 22 ran nonstop from the lobby to the eleventh floor while the remainder served every floor below the eleventh.[63][67][95][96] Three of the elevators continued to the underground concourse, although the elevators did not descend to the concourse except during emergencies.[95]

With a total rentable floor space of 877,900 square feet (81,560 m2), some of which was taken by the H&M Railroad,[27] the Fulton and Cortlandt Buildings were collectively billed as the largest office building in the world by floor area.[73][83] Each building contained 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2) of office space on each floor;[78] the Fulton Building had 18,000 square feet (1,700 m2) per floor and the Cortlandt Building 26,000 square feet (2,400 m2) per floor.[86] The towers could house a combined ten thousand tenants[97] across 4,000 offices.[24][73][83] At ground level, the buildings contained glass-enclosed shopping arcades that were "much larger than the famous European arcades".[67][98]

Basements

[edit]There were three stories of basements beneath the office buildings.[7][31] The first basement level was a shopping and waiting concourse directly below the street.[26][73] The second basement level contained the H&M platforms.[31][63][78] The third and lowest level contained the baggage room, electrical substation, and an engine and boiler room for the substation.[63][76] The depth of the H&M platforms was mandated by the city's Rapid Transit Railroad Commission. To provide space for potential north–south subway lines in Lower Manhattan, the roof of any "tunnel railroad" in the area had to be at least 20 feet (6.1 m) below any north–south street.[9]

Four cement ramps, two each from Cortlandt and Fulton Streets,[99] descended to the first basement level.[31][63][78] The floor surface of each ramp is made of a compound of cement and carborundum.[96] The original plans had called for one ramp each from Cortlandt and Fulton Streets and two from Dey Street, but the engineers deemed this to be impractical.[75] There were also two bluestone staircases from Dey Street.[96][99] At the end of each ramp or staircase, Karl Bitter designed a large clock face, and there was also a steel and glass marquee protruding onto the sidewalk.[96] According to Landau and Condit, "At full capacity, the Hudson Terminal could accommodate 687,000 people per day; in comparison, Pennsylvania Station (1902–1910) was designed with a capacity of 500,000."[64]

Facilities

[edit]The concourse, on the first basement level, contained ticket offices, waiting rooms, and some retail shops.[26][73][19] It measured 430 by 185 feet (131 by 56 m), much of which was open pedestrian space. The floor of the concourse was made of white terracotta with colored mosaic bands, while the columns and walls were made of plaster wainscoted with white terracotta.[19][96] The concourse contained a dropped ceiling, concealing some utility pipes and wires placed beneath the main ceiling.[13]

The basements were equipped with baggage handling facilities for the baggage trains traveling on Track 5. Two freight elevators carried baggage from Dey Street to the westernmost side platform or the baggage room in the third basement. Four elevators also transported baggage from the baggage room to the end of each of the island platforms.[100][101] Each of the freight elevators had a capacity of 13,000 pounds (5,900 kg), while each of the island-platform elevators had a capacity of 8,000 to 13,000 pounds (3,600 to 5,900 kg). Thus, baggage could be transported to trains on any of the five tracks.[101] The basements also contained a training school and break rooms for the H&M Railroad, as well as an ice-making plant, elevator hydraulic pumps, a generating plant, and a storage battery.[68][102][101]

Hudson Terminal's electrical substation consisted of two 1,500-kilowatt (2,000 hp) rotary converters for the railroad and four 750-kilowatt (1,010 hp) rotaries for the buildings.[63][76] This equipment was placed 75.8 feet (23.1 m) below ground level at Church Street.[75] From the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse in Jersey City, an 11,000-volt line of alternating current transmitted power to Hudson Terminal, where it was converted to 625 volts of direct current for the railroad and 240V DC for the offices.[102]

Substructure

[edit]The O'Rourke Engineering and Contracting Company were hired to build the complex's foundation.[65][87] The foundation used irregular framing because of the presence of the tracks on the second basement level, and the cofferdam was said to be five times larger than any other similar structure previously constructed.[20]

The perimeter of the foundation was excavated using 51 pneumatic caissons,[75][103] drilled to depths of between 75 and 98 feet (23 and 30 m), with an average depth of 80 feet (24 m).[20][89] This required the underpinning of every building nearby.[20] The caissons were made of reinforced concrete with 8-foot-thick (2.4 m) walls. At this location, the underlying rock layer descended a maximum of 110 feet (34 m) beneath Church Street. Within the interiors of the enclosed cofferdam, 115 circular pits and 32 rectangular pits were dug. The steel columns supporting the superstructure were then placed in the pits; they weighed up to 26 short tons (23 long tons; 24 t) and could carry loads of 1,725 short tons (1,540 long tons; 1,565 t).[75][103] The entire lot area was then excavated to the second basement level. Part of the third basement was also excavated down to bedrock.[103] Overall, 238,000 cubic yards (182,000 m3) of earth were excavated manually and 80,000 cubic yards (61,000 m3) excavated via caissons.[102]

The main girders at the Hudson Terminal station's platform level were 48 inches (1,200 mm) deep with flanges 16 inches (410 mm) wide. The floor of this level was a Portland concrete slab 36 inches (910 mm) thick.[104] The platforms contained columns at intervals of about every 20 feet (6.1 m).[59] Some of the girders in the substructure were spaced irregularly because of the placement of the railroad platforms at the second basement level. Heavy sets of three distributing girders, encased in concrete, were used in these locations to support the weight of the Fulton and Cortlandt Buildings.[89][19] Dey Street was carried above the mezzanine via a series of plate girders and I-beams, which formed a "skeleton platform" measuring about 180 ft (55 m) long by 27 ft (8.2 m) wide.[105] The structure carrying Dey Street could accommodate loads of up to 1,400 psf (67 kPa).[94] In total, the substructure included 11,000 cubic yards (8,400 m3) of concrete and 6,267 short tons (5,596 long tons; 5,685 t) of structural steel.[102]

Notable incidents

[edit]During the complex's existence, the buildings experienced several incidents. Within a year of the office building's opening, in 1909, a man died after falling from a window in the Fulton Building;[106] other deaths from falling occurred in 1927[107] and 1940.[108] A bag full of explosives was found in the terminal in 1915, with enough explosives to blow up several buildings of the Hudson Terminal towers' size.[109] The elevators were also involved in several accidents: two people were slightly injured by a falling elevator in 1923,[110] and a woman was killed two years later after being trapped in an elevator.[111][112] Phillips Petroleum Company executive Taylor S. Gay was also shot and killed in the terminal in 1962.[113]

There were several incidents in the H&M station as well. In 1937, a 5-car H&M train crashed into a wall, injuring 33 passengers.[114] Twenty-six people were injured in a 1962 crash between two H&M trains at the terminal.[115]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The H&M was also intended to serve the Communipaw Terminal, but this connection was not built.[8]

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Hudson Terminal was the first such development over a railroad or subway loop, but not the first development to be planned as such. A late-19th century plan for the Manhattan Municipal Building, ultimately completed in 1914, had included office space over a subway loop.[28]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "$21,000,000 Company for Hudson Tunnels; Will Also Build Ninth Street and Sixth Avenue Subways". The New York Times. January 10, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ "Tunnel Companies Join". New-York Tribune. January 10, 1905. p. 14. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Buying by Speculators Near Tunnel Terminal; Frequent Purchases on Dey, Fulton, and Vesey Streets". The New York Times. February 26, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ The Commercial & Financial Chronicle ...: A Weekly Newspaper Representing the Industrial Interests of the United States. William B. Dana Company. 1914.

- ^ "$100,000,000 Capital for M'Adoo Tunnels; Railroad Commission Agrees to Issuance of Big Mortgage". The New York Times. December 12, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "McAdoo Co. May Use Pennsylvania Depot". The New York Times. September 2, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Permanent WTC PATH Terminal: Environmental Impact Statement. 2007. p. 1.2 to 1.3.

- ^ "M'Adoo To Extend Hudson Tunnels". The New York Times. October 21, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davies & Wells 1910, p. 33.

- ^ "Sites to Be Taken for Two Great Buildings; Tunnel Project at Church and Cortlandt Streets Now Affects an Area of 62,000 Square Feet – World's Largest Skyscrapers to be Built". The New York Times. November 19, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Satow, Julie (April 8, 2016). "Before the Trumps, There Were the Wendels". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "John G. Wendel, Old School Millionaire". McClure's Magazine. Library of American civilization. No. v. 39. S.S. McClure. 1912. p. 136.

- ^ a b c d American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 326.

- ^ American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Davies & Wells 1910, p. 35.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field". The New York Times. July 14, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Hudson Companies.: Chief Engineer's Report of Progress of Construction. Sixteen Thousand Feet of Tunnel Already Completed". Wall Street Journal. February 14, 1907. p. 6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 129151670. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landau & Condit 1996, p. 328.

- ^ a b c d e "Hudson and Manhattan Railroad". Electric Railroads. No. 27. Electric Railroaders Association. August 1959. pp. 5–6. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Real Estate in 1907.; Shrinkage of Nearly 40 Per Cent. in the Number of Conveyances in the Borough of Manhattan". The New York Times. January 5, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "M',adoo Co. May Use Pennsylvania Depot; Wall Street Hears That Negotiations to That End Are Now Going on". The New York Times. September 2, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A $5,000,000 Tunnel Station". New-York Tribune. April 3, 1907. p. 8. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Taft, William H. (July 20, 1909). "40,000 Celebrate New Tubes' Opening; Downtown McAdoo Tunnels to Jersey City Begin Business with a Rush". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Under the Hudson by Four Tubes Now; Second Pair of McAdoo Tunnels to Jersey City Will Open To-morrow". The New York Times. July 18, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Condit, C.W. (1980). The Port of New York: A history of the rail terminal system from the beginnings to Pennsylvania Station. University of Chicago Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-226-11460-6. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 367.

- ^ "Hudson Terminal Buildings.: About 99 Per Cent. Of Space Occupied and Surplus for Year is $1,059,282". Wall Street Journal. December 19, 1911. p. 6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 120234467. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Many Good Sales Show Broadening Market". New York Sun. February 29, 1912. p. 12. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Droege, John Albert (1916). Passenger Terminals and Trains. McGraw-Hill. pp. 157–159.

- ^ "315,724,808 Came or Left City in 1922". The New York Times. April 15, 1923. p. E1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "11-Million Valuation Cut On Building Is Affirmed: Hudson Terminal Ruling Upheld by Appellate Division". New York Herald Tribune. January 27, 1945. p. 8. ProQuest 1269827778. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Link Opened, to Aid Commuters; Underpass at Hudson Terminal Also Leads to Platform of Chambers St. Subway". The New York Times. March 16, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Ind. Subway Station Link To Hudson Tubes Opened". New York Herald Tribune. March 16, 1949. p. 24. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1325787400.

- ^ "For Uptown Plot $550,000". New-York Tribune. January 24, 1907. p. 14. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Hudson Terminal Buildings Have 87% of Space Leased: Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Co. Will Re- Ceive $1,400,000 Annually From Buildings, Beginning May 1". Wall Street Journal. April 15, 1910. p. 7. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 129251776. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Under the River to Jersey". New York Sun. February 16, 1908. p. 6. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mails Crowded Out". The New York Times. July 1, 1908. p. 3. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "To Restore Post Office.; Hudson Terminal Branch Will Have Increased Facilities". The New York Times. January 3, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Postoffice Opens Downtown Monday; Annex Combining 2 Big Units Will Occupy Five Floors of New Federal Building". The New York Times. September 29, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Big Space Taken by U.S. Agencies; 180,000 Square Feet Leased at 30 and 50 Church St". The New York Times. March 23, 1962. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 56.

- ^ "Hudson Tubes File Bankruptcy Plea; H. & M. Line, Unable to Meet Debts, Acts to Reorganize – Losses Since '52 Cited". The New York Times. November 20, 1954. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8135-2742-0.

- ^ "Hudson & Manhattan Offered $15,250,000 For 2 Office Buildings". Wall Street Journal. December 30, 1958. p. 11. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132363590. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Levinson, Leonard Louis (1961). Wall Street. New York: Ziff Davis Publishing. p. 346.

- ^ Grutzner, Charles (January 27, 1960). "A World Center of Trade Mapped Off Wall Street" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Grutzner, Charles (December 29, 1961). "Port Unit Backs Linking of H&M and Other Lines" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ Wright, George Cable (January 23, 1962). "2 States Agree on Hudson Tubes and Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ Burks, Edward C. (October 19, 1971). "World Trade Center Rising In Noisy, Confusing World". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Iglauer, Edith (November 4, 1972). "The Biggest Foundation". The New Yorker.

- ^ Carroll, Maurice (December 30, 1968). "A Section of the Hudson Tubes Is Turned Into Elevated Tunnel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ "PATH Station Will Close Friday for 3-Day Changeover". Wall Street Journal. June 28, 1971. p. 3. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 133597796. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Burks, Edward C. (July 7, 1971). "New PATH Station Opens Downtown" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 74. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "Firemen Set a Blaze in an Empty 22-Story Building Here to Test the Safety of Stairwell Evacuation". The New York Times. April 16, 1972. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Vincent (April 16, 1972). "Chiefs Play Arson in Skyscraper". New York Daily News. p. 232. Retrieved October 2, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "College Works With Firemen in Safety Test". New York Daily News. December 10, 1972. p. 154. Retrieved October 2, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Dunlap, David W. (July 25, 2005). "Below Ground Zero, Stirrings of Past and Future". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ The Associated Press (August 20, 2011). "Decisive action by PATH employees kept 9/11 riders from danger". NJ.com. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (October 26, 2008). "Another Ghost from Ground Zero's Past Fades Away". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Most Notable Work of the Era" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 84, no. 2158. July 24, 1909. pp. 163–164 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 437.

- ^ a b c d Engineering Record 1907, p. 123.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c "The Church Street Terminal Buildings for the Hudson Tunnels". The Iron Age. David Williams. 1906. p. 1638.

- ^ a b c d e Wingate, C.F.; Meyer, H.C. (1909). The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer. McGraw Publishing Company. p. 108.

- ^ American Institute of Architects 1909, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b c Fitzherbert, Anthony (June 1964). "The Public Be Pleased: William Gibbs McAdoo and the Hudson Tubes". Electric Railroaders' Association. Retrieved April 24, 2018 – via nycsubway.org.

- ^ a b c American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 36.

- ^ a b Davies & Wells 1910, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shoppell's Homes, Decorations, Gardens. Co-Operative Architects. November 1907. p. 15.

- ^ American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e Davies & Wells 1910, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d "Opening of the Jersey City Branch of the Hudson & Manhattan Tunnels". Electrical World. McGraw-Hill. 1909. p. 182.

- ^ a b Brennan, Joseph. "Abandoned Stations : Hudson Terminal". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "To Open the Downtown Tunnels to Jersey on June 1" (PDF). New York Press. January 17, 1909. p. 1. Retrieved May 1, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ "M'adoo Would Build a West Side Subway; From 34th St. Down Broadway, Linking Penna. Tubes with All Downtown and His Own". The New York Times. September 16, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Davies, John Vipond (1910). "The Tunnel Construction of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 49, no. 195. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. pp. 164–187. JSTOR 983892.

- ^ Crowell, Paul (September 10, 1932). "Gay Midnight Crowd Rides First Trains in the Subway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Hudson Tube Terminal Plans Are Announced; Largest Office Building in the World at Manhattan End". The New York Times. December 23, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 351.

- ^ Davies & Wells 1910, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b "The Increasing Marvels of Lower Manhattan; Group of Skyscrapers Just Completed or in Process of Construction Will Add Seventy-seven Acres of Floor Space to City's Business Section. Caisson System of Building, First Used in 1892, Has Made the Giant Structures Possible by Overcoming Difficulties Caused by Manhattan's Sand Soil". The New York Times. October 6, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Three Great Contracts". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 77, no. 1994. June 2, 1906. p. 1043 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 392.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Engineering Record 1907, p. 121.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Architects Council of New York City (1909). The New York Architect. p. 135.

- ^ New York (N Y. ) Board of Estimate and Apportionment (1913). Minutes of the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the City of New York. M. B. Brown Printing & Binding Company. p. 3030.

- ^ Journal of Proceedings. 1913. p. 3611. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, p. 122.

- ^ a b American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e Davies & Wells 1910, p. 38.

- ^ "Directors Quit New York Life" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. April 9, 1908. p. 4. Retrieved May 1, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 327.

- ^ a b American Institute of Architects 1909, pp. 42–43.

- ^ American Institute of Architects 1909, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Davies & Wells 1910, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 40.

- ^ a b c American Institute of Architects 1909, p. 39.

- ^ Davies & Wells 1910, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, pp. 121–133.

- ^ "Falls 11 Stories, Dead: Body of E. G. Long Found on Skylight Window in His Office on 13th Floor of Hudson Terminal Building Discovered Wide Open". New-York Tribune. May 19, 1909. p. 1. ProQuest 572144713. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Salesman Jumps 19 Stories to Death; Falls From the Twenty-third Floor of Hudson Terminal to Roof of Extension". The New York Times. October 11, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Dies in 11-story Leap; Jobless Civil Engineer Leaps From Hudson Terminal". The New York Times. September 14, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Checked Explosive in Hudson Terminal; Enough Nitroglycerine to Blow Up a Block Left There by a Yeggman on Jan. 19. Clerk Tossed It About and Detectives, Not Knowing Contents of Bag, Swung It Carelessly While Going Through Streets". The New York Times. February 2, 1915. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "2 Only Slightly Hurt in 22-Story Elevator Drop: Water Cushion at Base of Shaft Prevents Tragedy at Hudson Terminal Building". New-York Tribune. October 14, 1923. p. 16. ProQuest 1237296996. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Elevator Crushes Woman to Death; Victim Faints as Express Car Starts, and is Caught Between the Floor and Shaft Door. Operator is Arrested Twelve Other Passengers Witness Accident in the Hudson Terminal Building". The New York Times. September 18, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Elevator Crushes Woman to Death; Pens In Passengers: Miss Pearl Thompson Dies in Express Car in Hudson Terminal Bldg.; Operator Held on Homicide Charge". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. September 18, 1925. p. 18. ProQuest 1112831993. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Oil Official Dies of Gunshot; Secretary's Brother Arraigned". The New York Times. June 13, 1962. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "21 Hurt in Accident in Hudson Terminal; Car Jumps Tracks and Crashes Into Wall". The New York Times. August 23, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "26 Hurt in Crash of 2 Tubes Trains; One Rams Into Back End of Second in Hudson Station --3 Persons in Hospital". The New York Times. October 16, 1962. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- Davies, J Vipond; Wells, J Hollis (January 19, 1910). "A Terminal Station". The American Architect. Vol. 97, no. 1778. pp. 32–38.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "The Hudson Companies' Building, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 56. August 3, 1907. pp. 121–123.

- The relations of railways to city development; papers read before the American Institute of Architects. American Institute of Architects. December 16, 1909.

External links

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

Media related to Hudson Terminal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hudson Terminal at Wikimedia Commons