Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Graphics software

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

In computer graphics, graphics software refers to a program or collection of programs that enable a person to manipulate images or models visually on a computer.[1]

Computer graphics can be classified into two distinct categories: raster graphics and vector graphics, with further 2D and 3D variants. Many graphics programs focus exclusively on either vector or raster graphics, but there are a few that operate on both. It is simple to convert from vector graphics to raster graphics, but going the other way is harder. Some software attempts to do this.

In addition to static graphics, there are animation and video editing software. Different types of software are often designed to edit different types of graphics such as video, photos, and vector-based drawings. The exact sources of graphics may vary for different tasks, but most can read and write files.[2]

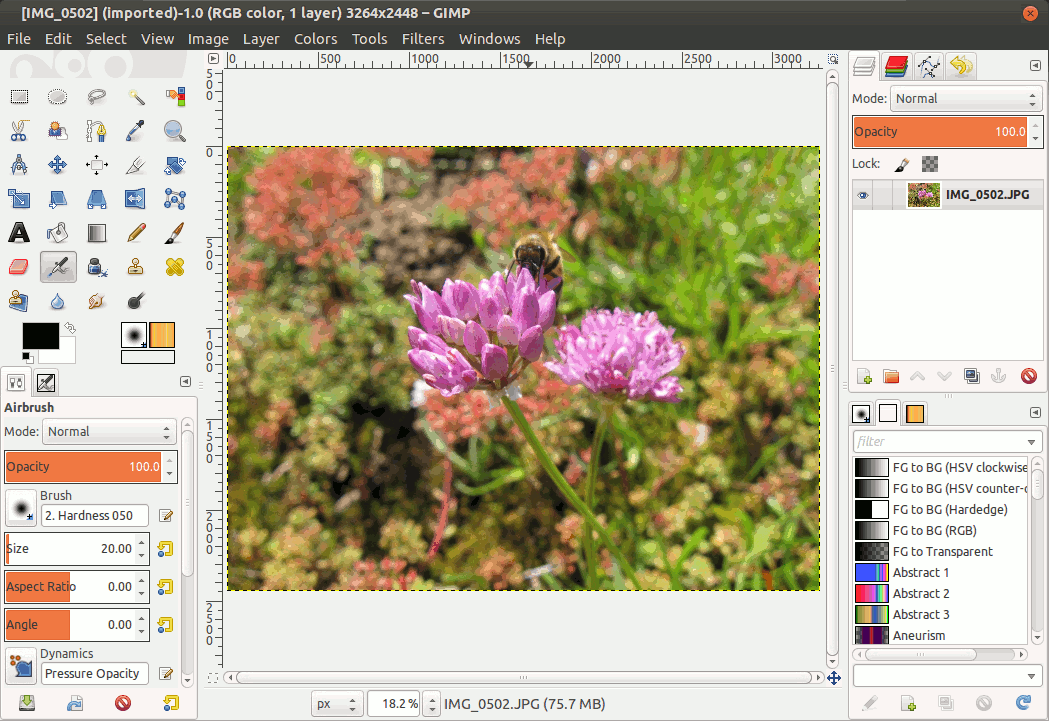

Most graphics programs have the ability to import and export one or more graphics file formats, including those formats written for a particular computer graphics program. Such programs include, but are not limited to: GIMP, Adobe Photoshop, CorelDRAW, Microsoft Publisher, Picasa, etc.[3]

The use of a swatch is a palette of active colours that are selected and rearranged by the preference of the user. A swatch may be used in a program or be part of the universal palette on an operating system. It is used to change the colour of a text or image and in video editing. Vector graphics animation can be described as a series of mathematical transformations that are applied in sequence to one or more shapes in a scene. Raster graphics animation works in a similar fashion to film-based animation, where a series of still images produces the illusion of continuous movement.

History

[edit]SuperPaint was one of the earliest graphics software applications, first conceptualized in 1972 and achieving its first stable image in 1973[4]

Fauve Matisse (later Macromedia xRes) was a pioneering program of the early 1990s, notably introducing layers in customer software.[5]

Currently Adobe Photoshop is one of the most used and best-known graphics programs in the Americas, having created more custom hardware solutions in the early 1990s, but was initially subject to various litigation. GIMP is a popular open-source alternative to Adobe Photoshop.

See also

[edit]- Comparison of raster graphics editors

- Comparison of vector graphics editors

- List of 2D graphics software

- List of 2D animation software

- List of 3D animation software

- List of 3D modeling software

- List of 3D rendering software

- List of digital art software

- Graphic art software

- Image morphing software

- Image conversion

- imc FAMOS (1987), graphical data analysis

- Raster graphics editor

- Vector graphics editor

References

[edit]- ^ "What is Graphics Software?". GeeksforGeeks. 2022-08-09. Archived from the original on 2023-07-20. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ "Software Graphic: graphics software". elearning.reb.rw. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ "Software Graphic: Graphics Software". elearning.reb.rw. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ Alonso, Bogar (2013-05-28). "The 1970s Graphics Program That Spurred Space Exploration, Computer Picassos and Pixar". Vice. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ Macromedia Matisse Archived 2017-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Reign of Toads Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine