Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Intermetallic

View on Wikipedia

An intermetallic (also called intermetallic compound, intermetallic alloy, ordered intermetallic alloy, long-range-ordered alloy) is a type of metallic alloy that forms an ordered solid-state compound between two or more metallic elements. Intermetallics are generally hard and brittle, with good high-temperature mechanical properties.[1][2][3] They can be classified as stoichiometric or nonstoichiometic.[1]

The term "intermetallic compounds" applied to solid phases has long been in use. However, Hume-Rothery argued that it misleads, suggesting a fixed stoichiometry and a clear decomposition into species.[4]

Definitions

[edit]Research definition

[edit]In 1967 Gustav Ernst Robert Schulze defined intermetallic compounds as solid phases containing two or more metallic elements, with optionally one or more non-metallic elements, whose crystal structure differs from that of the other constituents.[5] This definition includes:

- Electron (or Hume-Rothery) compounds

- Size packing phases. e.g., Laves phases, Frank–Kasper phases [6] and Nowotny phases

- Zintl phases

The definition of metal includes:[citation needed]

- Post-transition metals, i.e. aluminium, gallium, indium, thallium, tin, lead, and bismuth.

- Metalloids, e.g., silicon, germanium, arsenic, antimony and tellurium.

Homogeneous and heterogeneous solid solutions of metals, and interstitial compounds such as carbides and nitrides are excluded under this definition. However, interstitial intermetallic compounds are included, as are alloys of intermetallic compounds with a metal.[citation needed]

Common use

[edit]In common use, the research definition, including post-transition metals and metalloids, is extended to include compounds such as cementite, Fe3C. These compounds, sometimes termed interstitial compounds, can be stoichiometric, and share properties with the above intermetallic compounds.[citation needed]

Complexes

[edit]The term intermetallic is used[7] to describe compounds involving two or more metals such as the cyclopentadienyl complex Cp6Ni2Zn4.

B2

[edit]

A B2 (also known as cesium chloride structure type) intermetallic compound has equal numbers of atoms of two metals, such as aluminium-iron, and aluminium-nickel, arranged as two interpenetrating simple cubic lattices of the component metals. [8]

Properties

[edit]Intermetallic compounds are generally brittle at room temperature and have high melting point, though many also exhibit metallic conductivity or semiconducting behavior depending on the degree of covalent bonding. Cleavage or intergranular fracture modes are typical of intermetallics due to limited independent slip systems required for plastic deformation. However, some intermetallics have ductile fracture modes such as Nb–15Al–40Ti. Others can exhibit improved ductility by alloying with other elements to increase grain boundary cohesion. Alloying of other materials such as boron to improve grain boundary cohesion can improve ductility.[9] They may offer a compromise between ceramic and metallic properties when hardness and/or resistance to high temperatures is important enough to sacrifice some toughness and ease of processing. They can display desirable magnetic and chemical properties, due to their strong internal order and mixed (metallic and covalent/ionic) bonding, respectively. Intermetallics have given rise to various novel materials developments.[citation needed]

| Intermetallic Compound | Melting Temperature

(°C) |

Density

(kg/m3) |

Young's Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeAl | 1250–1400 | 5600 | 263 |

| Ti3Al | 1600 | 4200 | 210 |

| MoSi2 | 2020 | 6310 | 430 |

Applications

[edit]Examples include alnico and the hydrogen storage materials in nickel metal hydride batteries. Ni3Al, which is the hardening phase in the familiar nickel-base super alloys, and the various titanium aluminides have attracted interest for turbine blade applications, while the latter is also used in small quantities for grain refinement of titanium alloys. Silicides, intermetallics involving silicon, serve as barrier and contact layers in microelectronics.[10] Others include:

- Magnetic materials e.g., alnico, sendust, Permendur, FeCo, Terfenol-D

- Superconductors e.g., A15 phases, niobium-tin

- Hydrogen storage e.g., AB5 compounds (nickel metal hydride batteries)

- Shape memory alloys e.g., Cu-Al-Ni (alloys of Cu3Al and nickel), Nitinol (NiTi)

- Coating materials e.g., NiAl

- High-temperature structural materials e.g., nickel aluminide, Ni3Al

- Dental amalgams, which are alloys of intermetallics Ag3Sn and Cu3Sn

- Gate contact/ barrier layer for microelectronics e.g., TiSi2[11]: 692

- Laves phases (AB2), e.g., MgCu2, MgZn2 and MgNi2.

The unintended formation of intermetallics can cause problems. For example, intermetallics of gold and aluminium can be a significant cause of wire bond failures in semiconductor devices and other microelectronics devices. The management of intermetallics is a major issue in the reliability of solder joints between electronic components.[citation needed]

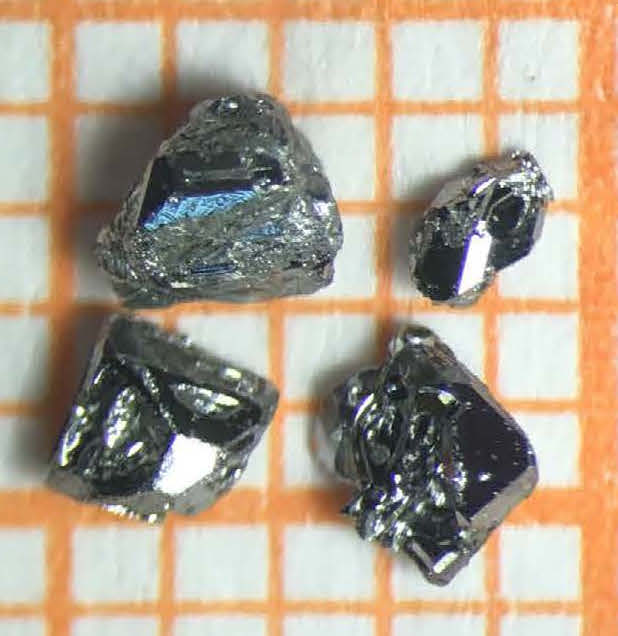

Intermetallic particles

[edit]Intermetallic particles often form during solidification of metallic alloys, and can be used as a dispersion strengthening mechanism.[1]

History

[edit]Examples of intermetallics through history include:

- Roman yellow brass, CuZn

- Chinese high tin bronze, Cu31Sn8

- Type metal, SbSn

- Chinese white copper, CuNi [12]

German type metal is described as breaking like glass, without bending, softer than copper, but more fusible than lead.[13]: 454 The chemical formula does not agree with the one above; however, the properties match with an intermetallic compound or an alloy of one.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Askeland, Donald R.; Wright, Wendelin J. (January 2015). "11-2 Intermetallic Compounds". The science and engineering of materials (Seventh ed.). Boston, MA. pp. 387–389. ISBN 978-1-305-07676-1. OCLC 903959750.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Panel On Intermetallic Alloy Development, Commission On Engineering And Technical Systems (1997). Intermetallic alloy development : a program evaluation. National Academies Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-309-52438-5. OCLC 906692179.

- ^ Soboyejo, W. O. (2003). "1.4.3 Intermetallics". Mechanical properties of engineered materials. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-8900-8. OCLC 300921090.

- ^ Hume-Rothery, W. (1955) [1948]. Electrons, atoms, metals and alloys (revised ed.). London: Louis Cassier Co., Ltd. pp. 316–317 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ G. E. R. Schulze: Metallphysik, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1967

- ^ Frank, F. C.; Kasper, J. S. (10 March 1958). "Complex alloy structures regarded as sphere packings. I. Definitions and basic principles". Acta Crystallographica. 11 (3): 184–190. Bibcode:1958AcCry..11..184F. doi:10.1107/S0365110X58000487.

- ^ Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-19957-5

- ^ "Wings of steel: An alloy of iron and aluminium is as good as titanium, at a tenth of the cost". The Economist. 7 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

E02715

- ^ Soboyejo, W. O. (2003). "12.5 Fracture of Intermetallics". Mechanical properties of engineered materials. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-8900-8. OCLC 300921090.

- ^ Murarka, S.P. (June 1993). "Metallization: theory and practice for VLSI and ULSI". Choice Reviews Online. 30 (10): 30–5612-30-5612. doi:10.5860/choice.30-5612 (inactive 1 July 2025). ISSN 0009-4978.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Ohring, Milton (2002). Materials Science of Thin Films. Academic Press. ISBN 9780125249751.

- ^ "The Art of War by Sun Zi: A Book for All Times". China Today. Archived from the original on 7 March 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Long, George (1843). "Type-pounding". The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. C. Knight.

Sources

[edit]- Sauthoff, Gerhard [in German] (1995). Intermetallics. Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–165. ISBN 978-3527293209.

- Sauthoff, Gerhard [in German] (2006). "Intermetallics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley Interscience. pp. 393–423. doi:10.1002/14356007.e14_e01.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

External links

[edit]- Intermetallics, scientific journal

- "Intermetallic Creation and Growth". Archived from the original on 18 December 2005.

- "IMPRESS Intermetallics project". www.spaceflight.esa.int. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- Video of an AB5 intermetallic compound solidifying/freezing. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015.

Intermetallic

View on GrokipediaDefinitions

Research Definition

In the research context, intermetallics are defined as solid phases containing at least two metallic elements, optionally including non-metallic elements, that form a distinct crystal structure different from those of their constituent elements.[4] This definition, originally proposed by Gustav E. R. Schulze in 1967, emphasizes the compound-like nature of these materials within metallurgical and materials science literature.[4] Key criteria distinguishing intermetallics include long-range atomic order, where atoms occupy specific lattice sites in a periodic arrangement; defined stoichiometry, typically stoichiometric or exhibiting a narrow range of homogeneity; and predominantly metallic bonding, often with contributions from covalent or ionic interactions that enhance stability.[5] These features result in unique phase behaviors, such as limited solubility and sharp phase boundaries, setting intermetallics apart from traditional alloys.[5] Unlike solid solutions, which involve random substitution of atoms on a disordered lattice, intermetallics maintain ordered superlattices that dictate their properties and limit compositional variability.[4] Representative binary examples include Ni₃Al, which adopts the L1₂ (ordered face-centered cubic) structure, and FeAl, which forms the B2 (ordered body-centered cubic) structure; these compounds illustrate how ordering influences mechanical and thermal characteristics, often leading to high melting points and inherent brittleness.[5]Common Usage

In engineering and materials science, the term intermetallic is commonly used in a broader sense than strict academic definitions, often including compounds formed between transition or post-transition metals and metalloids such as carbon or silicon, where ordered atomic arrangements dominate despite deviations from ideal stoichiometry. This inclusive interpretation recognizes phases like cementite (), an iron carbide essential to steel's hardness and wear resistance, as intermetallics due to their distinct crystal structure and metallic bonding characteristics.[6] Similarly, silicides involving post-transition elements, such as those in nickel- or iron-based alloys, are treated as intermetallics for their role in high-temperature applications, even when incorporating non-metallic silicon.[7] Non-stoichiometric variants further exemplify this practical usage, referring to phases with compositional flexibility around a nominal ratio while preserving long-range order in their atomic lattice. For example, certain transition metal silicides, like -NiSi, exhibit variable silicon content during growth but function as ordered intermetallics in microelectronic contacts and diffusion barriers. These variants highlight how engineering contexts prioritize functional behavior over precise stoichiometry, allowing for tunable properties in alloys.[8] The formation of intermetallics in this applied framework is often rationalized using the Hume-Rothery rules, which outline conditions favoring compounds over solid solutions: an atomic size factor where radii differences exceed 15% restricts random mixing and promotes ordered phases; electronegativity differences greater than about 0.4 units encourage directed bonding typical of intermetallics; and specific valence electron concentrations (e.g., 3/2 or 7/4 electrons per atom) stabilize particular structures like those in beta-brass analogs.[9] These guidelines, originally for solubility limits, are inverted in common practice to predict intermetallic stability across diverse systems.[10] Representative applications underscore this broader utility. The ordered intermetallic CuAu appears in copper-gold alloys for jewelry, enhancing tarnish resistance and achieving reddish hues in 14-18 karat formulations through its L1 structure. In lightweight structural materials, MgSi phases reinforce magnesium- or aluminum-based composites for automotive and aerospace components, offering a low density of 1.99 g/cm and high specific stiffness to reduce vehicle weight.[11][12]Molecular Complexes

Molecular intermetallic complexes are discrete, finite molecular entities featuring direct bonds between atoms of two or more different metals, typically stabilized by organometallic ligands such as cyclopentadienyl or phosphines, which prevent aggregation into bulk phases. These clusters represent molecular analogs of intermetallic compounds, enabling the isolation and study of intermetallic bonding in solution. Unlike extended solid-state intermetallics, they offer atomic precision for probing electronic and structural properties at the nanoscale.[13] The bonding in these complexes often follows Zintl-type models, involving electron transfer from electropositive to electronegative metals to achieve closed-shell configurations, or delocalized cluster bonding where electrons are shared across multiple metal centers, analogous to polyhedral boranes. For example, in bimetallic clusters, the electron count can adhere to adapted Wade-Mingos rules, promoting stability through multicenter orbitals. This delocalized nature contributes to unique electronic structures, such as superatom-like behavior in certain gold clusters.[13][14] Synthesis of molecular intermetallic complexes is predominantly achieved through organometallic routes, including the co-reduction of metal salts or organometallics with agents like sodium borohydride or alkali metals in coordinating solvents, in the presence of stabilizing ligands to control cluster size and prevent decomposition. A seminal example is the cyclopentadienyl-stabilized nickel-zinc cluster Cp₆Ni₂Zn₄, prepared by heating nickelocene (Cp₂Ni) with diethylzinc (Et₂Zn) in toluene, yielding an octahedral Ni₂Zn₄ core with six η⁵-Cp ligands and unusually electron-rich metal-metal bonds (average Ni-Zn distance of 2.52 Å).[15][13] These complexes exhibit properties distinct from bulk intermetallics, including high solubility in organic solvents due to the ligand shell, which enables solution-based spectroscopy and manipulation. They also show promise in catalysis, leveraging their precise atomic composition for selective reactions; for instance, gold-based clusters facilitate efficient CO₂ reduction or hydrogenation with turnover frequencies exceeding those of heterogeneous analogs. A notable example is the polynuclear gold cluster [Au₁₃(dppe)₆Cl₂]⁺, synthesized via reduction of Au(I)-dppe chloride precursors with NaBH₄, featuring an icosahedral Au₁₃ core with delocalized 8-electron superatomic orbitals and applications in photochemistry and sensing.[16]Crystal Structures

B2 Structure

The B2 structure, also known as the CsCl-type structure, represents a prototypical ordered intermetallic lattice in binary compounds, featuring a body-centered cubic (BCC) arrangement formed by two interpenetrating simple cubic sublattices of the constituent elements.[17] In this configuration, one sublattice consists of atoms of the first element positioned at the corners of the cubic unit cell, while the second sublattice places atoms of the other element at the body center, resulting in a stoichiometry of AB where A and B are the two distinct atomic species.[18] This atomic arrangement ensures that each atom has eight nearest neighbors of the opposite type, promoting unlike-atom bonding that distinguishes the ordered B2 phase from the disordered BCC solid solution.[19] The crystal symmetry of the B2 structure is described by the space group Pm-3m (no. 221), which reflects its high cubic symmetry and primitive unit cell containing two atoms.[18] Lattice parameters vary depending on the specific compound, but for the equiatomic NiAl intermetallic, the parameter is approximately 2.89 Å, corresponding to nearest-neighbor distances around 2.50 Å.[20] This compact geometry contributes to the structure's prevalence in systems exhibiting strong directional bonding while maintaining metallic character. The stability of the B2 structure is particularly favored in binary alloy systems where the constituent atoms possess similar atomic sizes (typically with radius ratios close to 1) and comparable electronegativities (differences often below 0.5 on the Pauling scale), which minimize strain and promote homogeneous electron distribution.[21] These factors enhance the energetic preference for ordering over phase separation or alternative lattices, as evidenced in computational studies mapping phase diagrams based on size and electronegativity parameters.[22] Representative examples of stable B2 phases include FeAl, NiAl, and CuZn (commonly known as β-brass), which demonstrate these compounds' utility in high-temperature applications due to their ordered lattice integrity.[23]Other Common Structures

Intermetallic compounds exhibit a diverse array of crystal structures classified primarily by their stoichiometry, such as AB, AB₂, and AB₃, and by topological features like Frank-Kasper polyhedra, which are coordination polyhedra with 12, 14, 15, or 16 nearest neighbors forming topologically close-packed arrangements.[24] These classifications highlight the ordered atomic arrangements that distinguish intermetallics from disordered solid solutions, with Frank-Kasper phases often featuring tetrahedral close-packing motifs.[25] Among the most prevalent are the Laves phases, which adopt AB₂ stoichiometry and crystallize in either cubic MgCu₂-type (C15, space group Fd-3m) or hexagonal MgZn₂-type (C14, space group P6₃/mmc) structures, both exemplifying Frank-Kasper topology through icosahedral coordination shells. Representative examples include TiCr₂, which forms the cubic MgCu₂ structure and exhibits high symmetry with A atoms coordinated to 12 B atoms and 4 A atoms,[26] and NbCo₂, which adopts the hexagonal MgZn₂ variant, featuring layered stacking of kagome nets and tetrahedral clusters. These phases are ubiquitous in binary and ternary systems due to their stability arising from geometric factors like atomic size ratios near 1.225. Heusler alloys represent another key class, typically following X₂YZ stoichiometry in full-Heusler structures (L2₁, space group Fm-3m), which consist of an ordered face-centered cubic lattice with X atoms at octahedral sites, Y at body-centered positions, and Z (often a main-group element) at cubic corners.[27] A classic example is Cu₂MnAl, a ferromagnetic full-Heusler alloy where the structure enables high spin polarization despite non-magnetic Cu and Al components.[27] Half-Heusler variants (XYZ, C1b structure, space group F-43m) feature a vacant tetrahedral site, as seen in compounds like NiMnSn, promoting half-metallicity suitable for spintronic applications.[27] Other notable structure types include the DO₁₉ phase, a hexagonal ordered arrangement (space group P6₃/mmc) common in AB₃ compounds like Ti₃Al, where Ti atoms occupy two distinct sites in a close-packed lattice with Al filling one-third of the octahedral interstices, enhancing phase stability in titanium aluminides. Similarly, the L1₂ structure is an ordered face-centered cubic variant (space group Pm-3m) observed in Ni₃Al, featuring a primitive cubic arrangement of Al atoms at cube corners surrounded by Ni in face-centered positions, which provides coherent precipitation strengthening in superalloys.[28] Many complex intermetallic structures reveal hierarchical relationships built from cluster-based units, such as icosahedral or Mackay clusters that serve as modular building blocks, allowing rational design by stacking these polyhedral motifs to form larger periodic lattices, as evidenced in analyses of over 4,000 compounds. This cluster hierarchy underscores the topological kinship among diverse phases, from simple binaries to quasicrystal approximants.Properties

Mechanical Properties

Intermetallic compounds are generally characterized by inherent brittleness, manifesting as low ductility at room temperatures, primarily due to their limited number of active slip systems and the presence of strong directional covalent bonding that restricts dislocation mobility.[29][30] This structural rigidity often leads to fracture toughness values below 5 MPa·m^{1/2}, making them prone to intergranular fracture under tensile loads.[31] Despite their brittleness, intermetallics demonstrate exceptional strength, particularly at elevated temperatures where many conventional metals soften. For instance, Ni₃Al exhibits high yield strength and maintains structural integrity up to approximately 1000°C, owing to its ordered crystal structure that suppresses dislocation climb and diffusion-mediated deformation.[32][33] Representative mechanical properties of select intermetallics highlight their high stiffness relative to density, enabling lightweight structural potential:| Intermetallic | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|

| FeAl | 263 | 5600 |

| Ti₃Al | 145 | 4200 |