Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

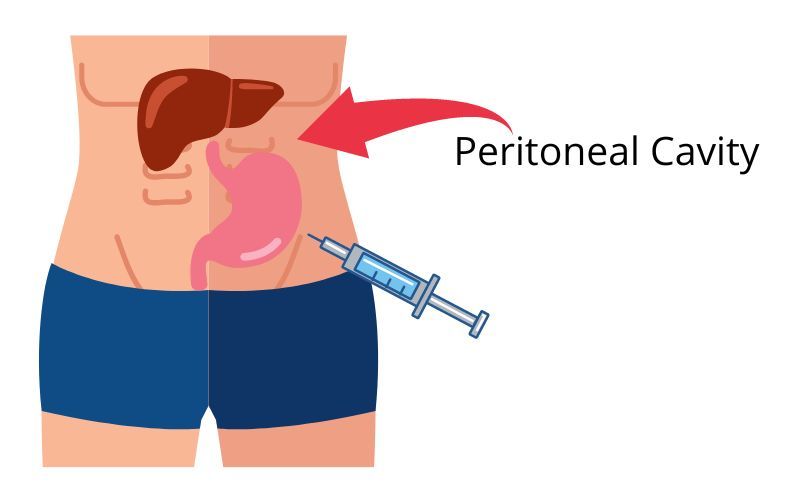

Intraperitoneal injection

View on WikipediaThis article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2024) |

| Intraperitoneal injection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Other names | IP injection |

| ICD-9-CM | 54.96-54.97 |

Intraperitoneal injection or IP injection is the injection of a substance into the peritoneum (body cavity). It is more often applied to non-human animals than to humans. In general, it is preferred when large amounts of blood replacement fluids are needed or when low blood pressure or other problems prevent the use of a suitable blood vessel for intravenous injection.[citation needed]

In humans, the method is widely used to administer chemotherapy drugs to treat some cancers, particularly ovarian cancer. Although controversial, intraperitoneal use in ovarian cancer has been recommended as a standard of care.[1] Fluids are injected intraperitoneally in infants, also used for peritoneal dialysis.[citation needed]

Intraperitoneal injections are a way to administer therapeutics and drugs through a peritoneal route (body cavity). They are one of the few ways drugs can be administered through injection, and have uses in research involving animals, drug administration to treat ovarian cancers, and much more. Understanding when intraperitoneal injections can be utilized and in what applications is beneficial to advance current drug delivery methods and provide avenues for further research. The benefit of administering drugs intraperitoneally is the ability for the peritoneal cavity to absorb large amounts of a drug quickly. A disadvantage of using intraperitoneal injections is that they can have a large variability in effectiveness and misinjection.[2] Intraperitoneal injections can be similar to oral administration in that hepatic metabolism could occur in both.

History

[edit]There are few accounts of the use of intraperitoneal injections prior to 1970. One of the earliest recorded uses of IP injections involved the insemination of a guinea-pig in 1957.[3] The study however did not find an increase in conception rate when compared to mating. In that same year, a study injected egg whites intraperitoneally into rats to study changes in "droplet" fractions in kidney cells. The study showed that the number of small droplets decreased after administration of the egg whites, indicating that they have been changed to large droplets.[4] In 1964, a study delivered chemical agents such as acetic acid, bradykinin, and kaolin to mice intraperitoneally in order to study a "squirming" response.[5] In 1967, the production of amnesia was studied through an injection of physostigmine.[6] In 1968, melatonin was delivered to rats intraperitoneally in order to study how brain serotonin would be affected in the midbrain.[7] In 1969, errors depending on a variety of techniques of administering IP injections were analyzed, and a 12% error in placement was found when using a one-man procedure versus a 1.2% error when using a two-man procedure.[8]

A good example of how intraperitoneal injections work is depicted through "The distribution of salicylate in mouse tissues after intraperitoneal injection" because it includes information on how a drug can travel to the blood, liver, brain, kidney, heart, spleen, diaphragm, and skeletal muscle once it has been injected intraperitoneally.[9]

These early uses of Intraperitoneal injections provide good examples of how the delivery method can be used, and provides a base for future studies on how to properly inject mice for research.

Use in humans

[edit]Currently, there are a handful of drugs that are delivered through intraperitoneal injection for chemotherapy. They are mitomycin C, cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, doxorubicin, premetrexed, and melphalan.[10] There needs to be more research done to determine appropriate dosing and combinations of these drugs to advance intraperitoneal drug delivery.

There are few examples of the use of intraperitoneal injections in humans cited in literature because it is mainly used to study the effects of drugs in mice. The few examples that do exist pertain to the treatment of pancreatic/ovarian cancers and injections of other drugs in clinical trials. One study utilized IP injections to study pain in the abdomen after a hysterectomy when administering anesthetic continuously vs patient-controlled.[11] The results depicted that ketobemidone consumption was significantly lower when patients controlled anesthetic through IP. This led to the patients being able to be discharged earlier than when anesthesia was administered continuously. These findings could be advanced by studying how the route of injection affects the organs in the peritoneal cavity.

In another Phase I clinical trial, patients with ovarian cancer were injected intraperitoneally with dl1520 in order to study the effects of a replication-competent/-selective virus.[12] The effects of this study were the onset of flu-like symptoms, emesis, and abdominal pain. The study overall defines appropriate doses and toxicity levels of dl1520 when injected intraperitoneally.

One study attempted to diagnose hepatic hydrothorax with the use of injecting Sonazoid intraperitoneally. Sonazoid was utilized to aid with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography by enhancing the peritoneal and pleural cavities.[13] This study demonstrates how intraperitoneal injections can be used to help diagnose diseases by providing direct access to the peritoneal cavity and affecting the organs in the cavity.

In a case of a ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma, it was reported that the patient was treated successfully through the use of an intraperitoneal injection of OK-432, which is an immunomodulatory agent.[14] The patient was a 51-year-old male who was hospitalized. The delivery of OK-432 occurred a total of four times in a span of one week. The results of this IP injection were the disappearance of the ascites associated with the rupture. This case is a good example of how IP injections can be used to deliver a drug that can help to treat or cure a medical diagnosis over the use of other routes of delivery. The results set a precedent of how other drugs may be delivered in this way to treat other similar medical issues after further research.

In 2018, a patient with stage IV ovarian cancer and peritoneal metastases was injected intraperitoneally with 12g of mixed cannabinoid before later being hospitalized.[15] The symptoms of this included impairment of cognitive and psychomotor abilities. Because of the injection of cannabis, the patient was predicted to have some level of THC in the blood from absorption. This case presents the question of how THC is absorbed in the peritoneal cavity. It also shows how easily substances are absorbed through the peritoneal cavity after an IP injection.

Overall, this section provides a few examples of the effects and uses of intraperitoneal injections in human patients. There are a variety of uses and possibilities for many more in the future with further research and approval.

Use in laboratory animals

[edit]Intraperitoneal injections are the preferred method of administration in many experimental studies due to the quick onset of effects post injection. This allows researchers to observe the effects of a drug in a shorter period of time, and allows them to study the effects of drugs on multiple organs that are in the peritoneal cavity at once. In order to effectively administer drugs through IP injections, the stomach of the animal is exposed, and the injection is given in the lower abdomen. The most efficient method to inject small animals is a two-person method where one holds the rodent and the other person injects the rodent at about 10 to 20 degrees in mice and 20 to 45 degrees in rats. The holder retains the arms of the animal and tilts the head lower than the abdomen to create optimal space in the peritoneal cavity.[2]

There has been some debate on whether intraperitoneal injections are the best route of administration for experimental animal studies. It was concluded in a review article that utilizing IP injections to administer drugs to laboratory rodents in experimental studies is acceptable when being applied to proof-of-concept studies.[16]

A study was conducted to determine the best route of administration to transplant mesenchymal stem cells for colitis. This study compared intraperitoneal injections, intravenous injections, and anal injections. It was concluded that the intraperitoneal injection had the highest survival rate of 87.5%.[17] This study shows how intraperitoneal injections can be more effective and beneficial than other traditional routes of administration.

One article reviews the injection of sodium pentobarbital to euthanize rodents intraperitoneally.[2] Killing the rodent through an intraperitoneal route was originally recommended over other routes such as inhalants because it was thought to be more efficient and ethical. The article overviews whether IP is the best option for euthanization based on evidence associated with welfare implications. It was concluded that there is evidence that IP may not be the best method of euthenasia due to possibilities of missinjection.

Another example of how intraperitoneal injections are used in studies involving rodents is the use of IP for micro-CT contrast enhanced detection of liver tumors.[18] Contrast agents were administered intraperitoneally instead of intravenously to avoid errors and challenges. It was determined that IP injections are a good option for Fenestra to quantify liver tumors in mice.

An example of how intraperitoneal injections can be optimized is depicted in a study where IP injections are used to deliver anesthesia to mice. This study goes over the dosages, adverse effects, and more of using intraperitoneal injections of anesthesia.[19]

An example of when intraperitoneal injections are not ideal is given in a study where the best route of administration was determined for cancer biotherapy.[20] It was concluded that IP administration should not be used over intravenous therapy due to high radiation absorption in the intestines. This shows an important limitation to the use of IP therapy.

The provided examples show a variety of uses for intraperitoneal injections in animals for in vitro studies. Some of the examples depict situations where IP injections are not ideal, while others prove the advantageous uses if this delivery method. Overall, many studies utilize IP injections to deliver therapeutics to lab animals due to the efficiency of the administration route.

References

[edit]- ^ Swart AM, Burdett S, Ledermann J, Mook P, Parmar MK (April 2008). "Why i.p. therapy cannot yet be considered as a standard of care for the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a systematic review". Annals of Oncology. 19 (4): 688–695. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm518. PMID 18006894.

- ^ a b c Laferriere CA, Pang DS (May 2020). "Review of Intraperitoneal Injection of Sodium Pentobarbital as a Method of Euthanasia in Laboratory Rodents". Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 59 (3): 254–263. doi:10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-19-000081 (inactive 1 July 2025). PMC 7210732. PMID 32156325.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Rowlands IW (November 1957). "Insemination of the guinea-pig by intraperitoneal injection". The Journal of Endocrinology. 16 (1): 98–106. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0160098. PMID 13491738.

- ^ Straus W (November 1957). "Changes in droplet fractions from rat kidney cells after intraperitoneal injection of egg white". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 3 (6): 933–947. doi:10.1083/jcb.3.6.933. PMC 2224142. PMID 13481027.

- ^ Whittle BA (September 1964). "Release of a kinin by intraperitoneal injection of chemical agents in mice". International Journal of Neuropharmacology. 3 (4): 369–378. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(64)90066-8. PMID 14334868.

- ^ Hamburg MD (May 1967). "Retrograde amnesia produced by intraperitoneal injection of physostigmine". Science. 156 (3777): 973–974. Bibcode:1967Sci...156..973H. doi:10.1126/science.156.3777.973. PMID 6067162. S2CID 46029262.

- ^ Anton-Tay F, Chou C, Anton S, Wurtman RJ (October 1968). "Brain serotonin concentration: elevation following intraperitoneal administration of melatonin". Science. 162 (3850): 277–278. Bibcode:1968Sci...162..277A. doi:10.1126/science.162.3850.277. JSTOR 1725071. PMID 5675470. S2CID 6484761.

- ^ Arioli V, Rossi E (April 1970). "Errors related to different techniques of intraperitoneal injection in mice". Applied Microbiology. 19 (4): 704–705. doi:10.1128/am.19.4.704-705.1970. PMC 376768. PMID 5418953. S2CID 237231042.

- ^ Sturman JA, Dawkins PD, McArthur N, Smith MJ (January 1968). "The distribution of salicylate in mouse tissues after intraperitoneal injection". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 20 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09619.x. PMID 4384147. S2CID 41866123.

- ^ de Bree E, Michelakis D, Stamatiou D, Romanos J, Zoras O (June 2017). "Pharmacological principles of intraperitoneal and bidirectional chemotherapy". Pleura and Peritoneum. 2 (2): 47–62. doi:10.1515/pp-2017-0010. PMC 6405033. PMID 30911633. S2CID 79678140.

- ^ Perniola A, Fant F, Magnuson A, Axelsson K, Gupta A (February 2014). "Postoperative pain after abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing continuous infusion vs patient-controlled intraperitoneal injection of local anaesthetic". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 112 (2): 328–336. doi:10.1093/bja/aet345. PMID 24185607.

- ^ Vasey PA, Shulman LN, Campos S, Davis J, Gore M, Johnston S, et al. (March 2002). "Phase I trial of intraperitoneal injection of the E1B-55-kd-gene-deleted adenovirus ONYX-015 (dl1520) given on days 1 through 5 every 3 weeks in patients with recurrent/refractory epithelial ovarian cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 20 (6): 1562–1569. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1562. PMID 11896105.

- ^ Tamano M, Hashimoto T, Kojima K, Maeda C, Hiraishi H (February 2010). "Diagnosis of hepatic hydrothorax using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with intraperitoneal injection of Sonazoid". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 25 (2): 383–386. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06002.x. PMID 19817961. S2CID 10043091.

- ^ Shiratori M, Nagashima I, Takada T, Morofuji S, Motomiya H, Matsuda K, et al. (2004). "Successful treatment of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma with intraperitoneal injection of OK-432". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 11 (6): 426–429. doi:10.1007/s00534-004-0921-8. PMID 15619020.

- ^ Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Song S, Solowij N, Reuter SE, Schneider J, et al. (September 2018). "Cannabinoid Disposition After Human Intraperitoneal Use: AnInsight Into Intraperitoneal Pharmacokinetic Properties in Metastatic Cancer". Clinical Therapeutics. 40 (9): 1442–1447. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.12.008. PMID 29317112. S2CID 41474813.

- ^ Al Shoyaib A, Archie SR, Karamyan VT (December 2019). "Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should it Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies?". Pharmaceutical Research. 37 (1) 12. doi:10.1007/s11095-019-2745-x. PMC 7412579. PMID 31873819.

- ^ Wang M, Liang C, Hu H, Zhou L, Xu B, Wang X, et al. (August 2016). "Intraperitoneal injection (IP), Intravenous injection (IV) or anal injection (AI)? Best way for mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for colitis". Scientific Reports. 6 (30696) 30696. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630696W. doi:10.1038/srep30696. PMC 4973258. PMID 27488951.

- ^ Sweeney N, Marchant S, Martinez JD (May 2019). "Intraperitoneal injections as an alternative method for micro-CT contrast enhanced detection of murine liver tumors". BioTechniques. 66 (5): 214–217. doi:10.2144/btn-2018-0162. hdl:10150/634184. PMID 31050302. S2CID 143433447.

- ^ Arras M, Autenried P, Rettich A, Spaeni D, Rülicke T (October 2001). "Optimization of intraperitoneal injection anesthesia in mice: drugs, dosages, adverse effects, and anesthesia depth". Comparative Medicine. 51 (5): 443–456. PMID 11924805.

- ^ Dou S, Smith M, Wang Y, Rusckowski M, Liu G (May 2013). "Intraperitoneal injection is not always a suitable alternative to intravenous injection for radiotherapy". Cancer Biotherapy & Radiopharmaceuticals. 28 (4): 335–342. doi:10.1089/cbr.2012.1351. PMC 3653381. PMID 23469942.