Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inverse trigonometric functions

View on Wikipedia

| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

| Reference |

| Laws and theorems |

| Calculus |

| Mathematicians |

In mathematics, the inverse trigonometric functions (occasionally also called antitrigonometric,[1] cyclometric,[2] or arcus functions[3]) are the inverse functions of the trigonometric functions, under suitably restricted domains. Specifically, they are the inverses of the sine, cosine, tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant functions,[4] and are used to obtain an angle from any of the angle's trigonometric ratios. Inverse trigonometric functions are widely used in engineering, navigation, physics, and geometry.

Notation

[edit]

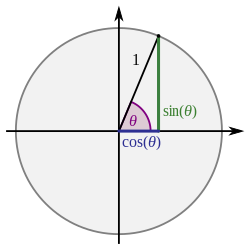

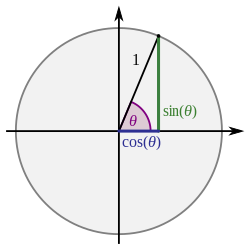

Several notations for the inverse trigonometric functions exist. The most common convention is to name inverse trigonometric functions using an arc- prefix: arcsin(x), arccos(x), arctan(x), etc.[1] (This convention is used throughout this article.) This notation arises from the following geometric relationships:[citation needed] when measuring in radians, an angle of θ radians will correspond to an arc whose length is rθ, where r is the radius of the circle. Thus in the unit circle, the cosine of x function is both the arc and the angle, because the arc of a circle of radius 1 is the same as the angle. Or, "the arc whose cosine is x" is the same as "the angle whose cosine is x", because the length of the arc of the circle in radii is the same as the measurement of the angle in radians.[5] In computer programming languages, the inverse trigonometric functions are often called by the abbreviated forms asin, acos, atan.[6]

The notations sin−1(x), cos−1(x), tan−1(x), etc., as introduced by John Herschel in 1813,[7][8] are often used as well in English-language sources,[1] much more than the also established sin[−1](x), cos[−1](x), tan[−1](x) – conventions consistent with the notation of an inverse function, that is useful (for example) to define the multivalued version of each inverse trigonometric function: However, this might appear to conflict logically with the common semantics for expressions such as sin2(x) (although only sin2 x, without parentheses, is the really common use), which refer to numeric power rather than function composition, and therefore may result in confusion between notation for the reciprocal (multiplicative inverse) and inverse function.[9]

The confusion is somewhat mitigated by the fact that each of the reciprocal trigonometric functions has its own name — for example, (cos(x))−1 = sec(x). Nevertheless, certain authors advise against using it, since it is ambiguous.[1][10] Another precarious convention used by a small number of authors is to use an uppercase first letter, along with a “−1” superscript: Sin−1(x), Cos−1(x), Tan−1(x), etc.[11] Although it is intended to avoid confusion with the reciprocal, which should be represented by sin−1(x), cos−1(x), etc., or, better, by sin−1 x, cos−1 x, etc., it in turn creates yet another major source of ambiguity, especially since many popular high-level programming languages (e.g. Mathematica and MAGMA) use those very same capitalised representations for the standard trig functions, whereas others (Python, SymPy, NumPy, Matlab, MAPLE, etc.) use lower-case.

Hence, since 2009, the ISO 80000-2 standard has specified solely the "arc" prefix for the inverse functions.

Basic concepts

[edit]

Principal values

[edit]Since none of the six trigonometric functions are one-to-one, they must be restricted in order to have inverse functions. Therefore, the result ranges of the inverse functions are proper (i.e. strict) subsets of the domains of the original functions.

For example, using function in the sense of multivalued functions, just as the square root function could be defined from the function is defined so that For a given real number with there are multiple (in fact, countably infinitely many) numbers such that ; for example, but also etc. When only one value is desired, the function may be restricted to its principal branch. With this restriction, for each in the domain, the expression will evaluate only to a single value, called its principal value. These properties apply to all the inverse trigonometric functions.

The principal inverses are listed in the following table.

| Name | Usual notation | Definition | Domain of x for real result | Range of usual principal value (radians) |

Range of usual principal value (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

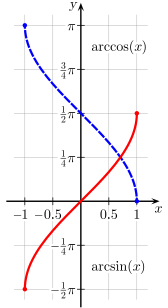

| arcsine | y = arcsin(x) | x = sin(y) | −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 | −π/2 ≤ y ≤ π/2 | −90° ≤ y ≤ 90° |

| arccosine | y = arccos(x) | x = cos(y) | −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 | 0 ≤ y ≤ π | 0° ≤ y ≤ 180° |

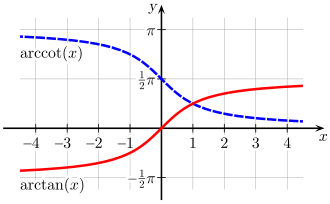

| arctangent | y = arctan(x) | x = tan(y) | all real numbers | −π/2 < y < π/2 | −90° < y < 90° |

| arccotangent | y = arccot(x) | x = cot(y) | all real numbers | 0 < y < π | 0° < y < 180° |

| arcsecant | y = arcsec(x) | x = sec(y) | |x| ≥ 1 | 0 ≤ y < π/2 or π/2 < y ≤ π | 0° ≤ y < 90° or 90° < y ≤ 180° |

| arccosecant | y = arccsc(x) | x = csc(y) | |x| ≥ 1 | −π/2 ≤ y < 0 or 0 < y ≤ π/2 | −90° ≤ y < 0 or 0° < y ≤ 90° |

Note: Some authors define the range of arcsecant to be ( or ),[12] because the tangent function is nonnegative on this domain. This makes some computations more consistent. For example, using this range, whereas with the range ( or ), we would have to write since tangent is nonnegative on but nonpositive on For a similar reason, the same authors define the range of arccosecant to be or

Domains

[edit]If x is allowed to be a complex number, then the range of y applies only to its real part.

The table below displays names and domains of the inverse trigonometric functions along with the range of their usual principal values in radians.

| Name |

Symbol | Domain | Image/Range | Inverse function |

Domain | Image of principal values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sine | ||||||||||

| cosine | ||||||||||

| tangent | ||||||||||

| cotangent | ||||||||||

| secant | ||||||||||

| cosecant |

The symbol denotes the set of all real numbers and denotes the set of all integers. The set of all integer multiples of is denoted by

The symbol denotes set subtraction so that, for instance, is the set of points in (that is, real numbers) that are not in the interval

The Minkowski sum notation and that is used above to concisely write the domains of is now explained.

Domain of cotangent and cosecant : The domains of and are the same. They are the set of all angles at which i.e. all real numbers that are not of the form for some integer

Domain of tangent and secant : The domains of and are the same. They are the set of all angles at which

Solutions to elementary trigonometric equations

[edit]Each of the trigonometric functions is periodic in the real part of its argument, running through all its values twice in each interval of

- Sine and cosecant begin their period at (where is an integer), finish it at and then reverse themselves over to

- Cosine and secant begin their period at finish it at and then reverse themselves over to

- Tangent begins its period at finishes it at and then repeats it (forward) over to

- Cotangent begins its period at finishes it at and then repeats it (forward) over to

This periodicity is reflected in the general inverses, where is some integer.

The following table shows how inverse trigonometric functions may be used to solve equalities involving the six standard trigonometric functions. It is assumed that the given values and all lie within appropriate ranges so that the relevant expressions below are well-defined. Note that "for some " is just another way of saying "for some integer "

The symbol is logical equality and indicates that if the left hand side is true then so is the right hand side and, conversely, if the right hand side is true then so is the left hand side (see this footnote[note 1] for more details and an example illustrating this concept).

| Equation | if and only if | Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for some | ||||||||

| for some | ||||||||

| for some | ||||||||

| for some | ||||||||

| for some | ||||||||

| for some | ||||||||

where the first four solutions can be written in expanded form as:

| Equation | if and only if | Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| or |

for some | |||||||

| or |

for some | |||||||

| or |

for some | |||||||

| or |

for some | |||||||

For example, if then for some While if then for some where will be even if and it will be odd if The equations and have the same solutions as and respectively. In all equations above except for those just solved (i.e. except for / and /), the integer in the solution's formula is uniquely determined by (for fixed and ).

With the help of integer parity it is possible to write a solution to that doesn't involve the "plus or minus" symbol:

- if and only if for some

And similarly for the secant function,

- if and only if for some

where equals when the integer is even, and equals when it's odd.

Detailed example and explanation of the "plus or minus" symbol ±

[edit]The solutions to and involve the "plus or minus" symbol whose meaning is now clarified. Only the solution to will be discussed since the discussion for is the same.

We are given between and we know that there is an angle in some interval that satisfies We want to find this The table above indicates that the solution is

which is a shorthand way of saying that (at least) one of the following statement is true:

- for some integer

or - for some integer

As mentioned above, if (which by definition only happens when ) then both statements (1) and (2) hold, although with different values for the integer : if is the integer from statement (1), meaning that holds, then the integer for statement (2) is (because ). However, if then the integer is unique and completely determined by If (which by definition only happens when ) then (because and so in both cases is equal to ) and so the statements (1) and (2) happen to be identical in this particular case (and so both hold). Having considered the cases and we now focus on the case where and So assume this from now on. The solution to is still which as before is shorthand for saying that one of statements (1) and (2) is true. However this time, because and statements (1) and (2) are different and furthermore, exactly one of the two equalities holds (not both). Additional information about is needed to determine which one holds. For example, suppose that and that all that is known about is that (and nothing more is known). Then and moreover, in this particular case (for both the case and the case) and so consequently, This means that could be either or Without additional information it is not possible to determine which of these values has. An example of some additional information that could determine the value of would be knowing that the angle is above the -axis (in which case ) or alternatively, knowing that it is below the -axis (in which case ).

Equal identical trigonometric functions

[edit]The table below shows how two angles and must be related if their values under a given trigonometric function are equal or negatives of each other.

| Equation | if and only if | Solution (for some ) | Also a solution to |

|---|---|---|---|

The vertical double arrow in the last row indicates that and satisfy if and only if they satisfy

- Set of all solutions to elementary trigonometric equations

Thus given a single solution to an elementary trigonometric equation ( is such an equation, for instance, and because always holds, is always a solution), the set of all solutions to it are:

| If solves | then | Set of all solutions (in terms of ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| then | ||||||||

| then | ||||||||

| then | ||||||||

| then | ||||||||

| then | ||||||||

| then | ||||||||

Transforming equations

[edit]The equations above can be transformed by using the reflection and shift identities:[13]

| Argument: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

These formulas imply, in particular, that the following hold:

where swapping swapping and swapping gives the analogous equations for respectively.

So for example, by using the equality the equation can be transformed into which allows for the solution to the equation (where ) to be used; that solution being: which becomes: where using the fact that and substituting proves that another solution to is: The substitution may be used express the right hand side of the above formula in terms of instead of

Relationships between trigonometric functions and inverse trigonometric functions

[edit]Trigonometric functions of inverse trigonometric functions are tabulated below. They may be derived from the Pythagorean identities. Another way is by considering the geometry of a right-angled triangle, with one side of length 1 and another side of length then applying the Pythagorean theorem and definitions of the trigonometric ratios. It is worth noting that for arcsecant and arccosecant, the diagram assumes that is positive, and thus the result has to be corrected through the use of absolute values and the signum (sgn) operation.

| Diagram | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

Relationships among the inverse trigonometric functions

[edit]

Complementary angles:

Negative arguments:

Reciprocal arguments:

The identities above can be used with (and derived from) the fact that and are reciprocals (i.e. ), as are and and and

Useful identities if one only has a fragment of a sine table:

Whenever the square root of a complex number is used here, we choose the root with the positive real part (or positive imaginary part if the square was negative real).

A useful form that follows directly from the table above is

- .

It is obtained by recognizing that .

From the half-angle formula, , we get:

Arctangent addition formula

[edit]This is derived from the tangent addition formula

by letting

In calculus

[edit]Derivatives of inverse trigonometric functions

[edit]The derivatives for complex values of z are as follows:

Only for real values of x:

These formulas can be derived in terms of the derivatives of trigonometric functions. For example, if , then so

Expression as definite integrals

[edit]Integrating the derivative and fixing the value at one point gives an expression for the inverse trigonometric function as a definite integral:

When x equals 1, the integrals with limited domains are improper integrals, but still well-defined.

Infinite series

[edit]Similar to the sine and cosine functions, the inverse trigonometric functions can also be calculated using power series, as follows. For arcsine, the series can be derived by expanding its derivative, , as a binomial series, and integrating term by term (using the integral definition as above). The series for arctangent can similarly be derived by expanding its derivative in a geometric series, and applying the integral definition above (see Leibniz series).

Series for the other inverse trigonometric functions can be given in terms of these according to the relationships given above. For example, , , and so on. Another series is given by:[14]

Leonhard Euler found a series for the arctangent that converges more quickly than its Taylor series:

(The term in the sum for n = 0 is the empty product, so is 1.)

Alternatively, this can be expressed as

Another series for the arctangent function is given by

where is the imaginary unit.[16]

Continued fractions for arctangent

[edit]Two alternatives to the power series for arctangent are these generalized continued fractions:

The second of these is valid in the cut complex plane. There are two cuts, from −i to the point at infinity, going down the imaginary axis, and from i to the point at infinity, going up the same axis. It works best for real numbers running from −1 to 1. The partial denominators are the odd natural numbers, and the partial numerators (after the first) are just (nz)2, with each perfect square appearing once. The first was developed by Leonhard Euler; the second by Carl Friedrich Gauss utilizing the Gaussian hypergeometric series.

Indefinite integrals of inverse trigonometric functions

[edit]For real and complex values of z:

For real x ≥ 1:

For all real x not between -1 and 1:

The absolute value is necessary to compensate for both negative and positive values of the arcsecant and arccosecant functions. The signum function is also necessary due to the absolute values in the derivatives of the two functions, which create two different solutions for positive and negative values of x. These can be further simplified using the logarithmic definitions of the inverse hyperbolic functions:

The absolute value in the argument of the arcosh function creates a negative half of its graph, making it identical to the signum logarithmic function shown above.

All of these antiderivatives can be derived using integration by parts and the simple derivative forms shown above.

Example

[edit]Using (i.e. integration by parts), set

Then

which by the simple substitution yields the final result:

Extension to the complex plane

[edit]

Since the inverse trigonometric functions are analytic functions, they can be extended from the real line to the complex plane. This results in functions with multiple sheets and branch points. One possible way of defining the extension is:

where the part of the imaginary axis which does not lie strictly between the branch points (−i and +i) is the branch cut between the principal sheet and other sheets. The path of the integral must not cross a branch cut. For z not on a branch cut, a straight line path from 0 to z is such a path. For z on a branch cut, the path must approach from Re[x] > 0 for the upper branch cut and from Re[x] < 0 for the lower branch cut.

The arcsine function may then be defined as:

where (the square-root function has its cut along the negative real axis and) the part of the real axis which does not lie strictly between −1 and +1 is the branch cut between the principal sheet of arcsin and other sheets;

which has the same cut as arcsin;

which has the same cut as arctan;

where the part of the real axis between −1 and +1 inclusive is the cut between the principal sheet of arcsec and other sheets;

which has the same cut as arcsec.

Logarithmic forms

[edit]These functions may also be expressed using complex logarithms. This extends their domains to the complex plane in a natural fashion. The following identities for principal values of the functions hold everywhere that they are defined, even on their branch cuts.

Generalization

[edit]Because all of the inverse trigonometric functions output an angle of a right triangle, they can be generalized by using Euler's formula to form a right triangle in the complex plane. Algebraically, this gives us:

or

where is the adjacent side, is the opposite side, and is the hypotenuse. From here, we can solve for .

or

Simply taking the imaginary part works for any real-valued and , but if or is complex-valued, we have to use the final equation so that the real part of the result isn't excluded. Since the length of the hypotenuse doesn't change the angle, ignoring the real part of also removes from the equation. In the final equation, we see that the angle of the triangle in the complex plane can be found by inputting the lengths of each side. By setting one of the three sides equal to 1 and one of the remaining sides equal to our input , we obtain a formula for one of the inverse trig functions, for a total of six equations. Because the inverse trig functions require only one input, we must put the final side of the triangle in terms of the other two using the Pythagorean Theorem relation

The table below shows the values of a, b, and c for each of the inverse trig functions and the equivalent expressions for that result from plugging the values into the equations above and simplifying.

The particular form of the simplified expression can cause the output to differ from the usual principal branch of each of the inverse trig functions. The formulations given will output the usual principal branch when using the and principal branch for every function except arccotangent in the column. Arccotangent in the column will output on its usual principal branch by using the and convention.

In this sense, all of the inverse trig functions can be thought of as specific cases of the complex-valued log function. Since these definition work for any complex-valued , the definitions allow for hyperbolic angles as outputs and can be used to further define the inverse hyperbolic functions. It's possible to algebraically prove these relations by starting with the exponential forms of the trigonometric functions and solving for the inverse function.

Example proof

[edit]Using the exponential definition of sine, and letting

(the positive branch is chosen)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Applications

[edit]Finding the angle of a right triangle

[edit]

Inverse trigonometric functions are useful when trying to determine the remaining two angles of a right triangle when the lengths of the sides of the triangle are known. Recalling the right-triangle definitions of sine and cosine, it follows that

Often, the hypotenuse is unknown and would need to be calculated before using arcsine or arccosine using the Pythagorean Theorem: where is the length of the hypotenuse. Arctangent comes in handy in this situation, as the length of the hypotenuse is not needed.

For example, suppose a roof drops 8 feet as it runs out 20 feet. The roof makes an angle θ with the horizontal, where θ may be computed as follows:

In computer science and engineering

[edit]Two-argument variant of arctangent

[edit]

The two-argument atan2 function computes the arctangent of y/x given y and x, but with a range of (−π, π]. In other words, atan2(y, x) is the angle between the positive x-axis of a plane and the point (x, y) on it, with positive sign for counter-clockwise angles (upper half-plane, y > 0), and negative sign for clockwise angles (lower half-plane, y < 0). It was first introduced in many computer programming languages, but it is now also common in other fields of science and engineering.

In terms of the standard arctan function, that is with range of (−π/2, π/2), it can be expressed as follows:

It also equals the principal value of the argument of the complex number x + iy.

This limited version of the function above may also be defined using the tangent half-angle formulae as follows: provided that either x > 0 or y ≠ 0. However this fails if given x ≤ 0 and y = 0 so the expression is unsuitable for computational use.

The above argument order (y, x) seems to be the most common, and in particular is used in ISO standards such as the C programming language, but a few authors may use the opposite convention (x, y) so some caution is warranted.

Arctangent function with location parameter

[edit]In many applications[17] the solution of the equation is to come as close as possible to a given value . The adequate solution is produced by the parameter modified arctangent function

The function rounds to the nearest integer.

Numerical accuracy

[edit]For angles near 0 and π, arccosine is ill-conditioned, and similarly with arcsine for angles near −π/2 and π/2. Computer applications thus need to consider the stability of inputs to these functions and the sensitivity of their calculations, or use alternate methods.[18]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The expression "LHS RHS" indicates that either (a) the left hand side (i.e. LHS) and right hand side (i.e. RHS) are both true, or else (b) the left hand side and right hand side are both false; there is no option (c) (e.g. it is not possible for the LHS statement to be true and also simultaneously for the RHS statement to be false), because otherwise "LHS RHS" would not have been written.

To clarify, suppose that it is written "LHS RHS" where LHS (which abbreviates left hand side) and RHS are both statements that can individually be either be true or false. For example, if and are some given and fixed numbers and if the following is written: then LHS is the statement "". Depending on what specific values and have, this LHS statement can either be true or false. For instance, LHS is true if and (because in this case ) but LHS is false if and (because in this case which is not equal to ); more generally, LHS is false if and Similarly, RHS is the statement " for some ". The RHS statement can also either true or false (as before, whether the RHS statement is true or false depends on what specific values and have). The logical equality symbol means that (a) if the LHS statement is true then the RHS statement is also necessarily true, and moreover (b) if the LHS statement is false then the RHS statement is also necessarily false. Similarly, also means that (c) if the RHS statement is true then the LHS statement is also necessarily true, and moreover (d) if the RHS statement is false then the LHS statement is also necessarily false.

References

[edit]- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1972). Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Arthur Graham; Frink, Fred Goodrich (Jan 1909). "Chapter II. The Acute Angle [14] Inverse trigonometric functions". Written at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Trigonometry. Vol. Part I: Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: Henry Holt and Company / Norwood Press / J. S. Cushing Co. - Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Massachusetts, USA. p. 15. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

[…] α = arcsin m: It is frequently read "arc-sine m" or "anti-sine m," since two mutually inverse functions are said each to be the anti-function of the other. […] A similar symbolic relation holds for the other trigonometric functions. […] This notation is universally used in Europe and is fast gaining ground in this country. A less desirable symbol, α = sin-1m, is still found in English and American texts. The notation α = inv sin m is perhaps better still on account of its general applicability. […]

- ^ Klein, Felix (1924) [1902]. Elementarmathematik vom höheren Standpunkt aus: Arithmetik, Algebra, Analysis (in German). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Berlin: J. Springer. Translated as Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint: Arithmetic, Algebra, Analysis. Translated by Hedrick, E. R.; Noble, C. A. Macmillan. 1932. ISBN 978-0-486-43480-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hazewinkel, Michiel (1994) [1987]. Encyclopaedia of Mathematics (unabridged reprint ed.). Kluwer Academic Publishers / Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-155608010-4. Bronshtein, I. N.; Semendyayev, K. A.; Musiol, Gerhard; Mühlig, Heiner. "Cyclometric or Inverse Trigonometric Functions". Handbook of Mathematics (6th ed.). Berlin: Springer. § 2.8, pp. 85–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-663-46221-8 (inactive 1 Jul 2025).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) However, the term "arcus function" can also refer to the function giving the argument of a complex number, sometimes called the arcus. - ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Inverse Trigonometric Functions". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Beach, Frederick Converse; Rines, George Edwin, eds. (1912). "Inverse trigonometric functions". The Americana: a universal reference library. Vol. 21.

- ^ Cook, John D. (11 Feb 2021). "Trig functions across programming languages". johndcook.com (blog). Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1919). A History of Mathematics (2 ed.). New York, NY: The Macmillan Company. p. 272.

- ^ Herschel, John Frederick William (1813). "On a remarkable Application of Cotes's Theorem". Philosophical Transactions. 103 (1). Royal Society, London: 8. doi:10.1098/rstl.1813.0005.

- ^ "Inverse trigonometric functions". Wiki. Brilliant Math & Science (brilliant.org). Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Korn, Grandino Arthur; Korn, Theresa M. (2000) [1961]. "21.2.-4. Inverse Trigonometric Functions". Mathematical handbook for scientists and engineers: Definitions, theorems, and formulars for reference and review (3 ed.). Mineola, New York, USA: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 811. ISBN 978-0-486-41147-7.

- ^ Bhatti, Sanaullah; Nawab-ud-Din; Ahmed, Bashir; Yousuf, S. M.; Taheem, Allah Bukhsh (1999). "Differentiation of Trigonometric, Logarithmic and Exponential Functions". In Ellahi, Mohammad Maqbool; Dar, Karamat Hussain; Hussain, Faheem (eds.). Calculus and Analytic Geometry (1 ed.). Lahore: Punjab Textbook Board. p. 140.

- ^ For example: Stewart, James; Clegg, Daniel; Watson, Saleem (2021). "Inverse Functions and Logarithms". Calculus: Early Transcendentals (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. § 1.5, p. 64. ISBN 978-1-337-61392-7.

- ^ Abramowitz & Stegun 1972, p. 73, 4.3.44

- ^ Borwein, Jonathan; Bailey, David; Gingersohn, Roland (2004). Experimentation in Mathematics: Computational Paths to Discovery (1 ed.). Wellesley, MA, USA: A. K. Peters. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-56881-136-9.

- ^ Hwang Chien-Lih (2005), "An elementary derivation of Euler's series for the arctangent function", The Mathematical Gazette, 89 (516): 469–470, doi:10.1017/S0025557200178404, S2CID 123395287

- ^ S. M. Abrarov and B. M. Quine (2018), "A formula for pi involving nested radicals", The Ramanujan Journal, 46 (3): 657–665, arXiv:1610.07713, doi:10.1007/s11139-018-9996-8, S2CID 119150623

- ^ when a time varying angle crossing should be mapped by a smooth line instead of a saw toothed one (robotics, astronomy, angular movement in general)[citation needed]

- ^ Gade, Kenneth (2010). "A non-singular horizontal position representation" (PDF). The Journal of Navigation. 63 (3). Cambridge University Press: 395–417. Bibcode:2010JNav...63..395G. doi:10.1017/S0373463309990415.

External links

[edit]Inverse trigonometric functions

View on GrokipediaNotation and Definitions

Standard Notation

Inverse trigonometric functions are the inverse relations of the six basic trigonometric functions—sine, cosine, tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant—serving primarily to recover angles from given ratios of sides in right triangles or from trigonometric values in broader contexts. The most common notations employ either an "arc" prefix or a superscript exponent: or for the inverse sine, or for the inverse cosine, or for the inverse tangent, or for the inverse cotangent, or for the inverse secant, and or for the inverse cosecant.[5] The arc- prefix notation originated in the 18th century with contributions from mathematicians like Euler, who used "A sin" in 1737, but the superscript notation was introduced by John Herschel in 1813; the former gained broader adoption in European texts by the early 20th century to mitigate confusion between inverse functions and trigonometric reciprocals (such as ).[6][6] In older mathematical literature and certain specialized fields like computer programming, abbreviated forms such as , , and are used for the principal inverse functions.[7]Principal Branches

Trigonometric functions like sine, cosine, and tangent are periodic with period and possess symmetries, such as , rendering them non-injective over the real numbers and thus multi-valued when inverted.[8] To define single-valued inverse functions, principal branches are established by restricting the output to specific intervals where the original functions are bijective on their domains.[8] These principal ranges are selected to ensure the inverse functions are continuous, to maintain symmetries (e.g., odd functions for arcsin and arctan), and to correspond to angles in the first and fourth quadrants for alignment with right-triangle conventions where angles are non-negative and acute or obtuse as needed.[9] The standard principal branches, as defined in authoritative mathematical references, are as follows:| Function | Principal Range |

|---|---|

Fundamental Properties

Domains and Ranges

The domains of inverse trigonometric functions are determined by the ranges of their corresponding trigonometric functions, ensuring that the inverses are well-defined and single-valued over the real numbers. Specifically, the arcsine function, , and arccosine function, , are defined for inputs in the closed interval , as these are the possible output values of the sine and cosine functions over their full real domains.[12] In contrast, the arctangent function, , and arccotangent function, , accept all real numbers as inputs (), reflecting the unbounded range of the tangent and cotangent functions within their principal periods. The arcsecant function, , and arccosecant function, , are defined for , corresponding to the ranges of secant and cosecant outside the open interval .[13] These domain restrictions arise from the periodic and non-injective nature of the trigonometric functions, which would otherwise yield multi-valued inverses without careful limitation to ensure real, unique outputs.[12] The ranges of these inverse functions, known as principal branches, are selected intervals where the original trigonometric functions are bijective, guaranteeing monotonicity and continuity within the defined domains. For instance, outputs values in , increasing monotonically from at to at . Similarly, ranges over , decreasing from to as goes from to . The function produces outputs in , approaching the asymptotes as tends to , while maintaining strict increase across all real inputs. The range is , decreasing from to over . For , the principal range is , and for , it is , both exhibiting discontinuities at points where the original functions are undefined, but monotonic in their respective subintervals.[13][12] Graphically, these domains and ranges illustrate the inverses as reflections of the restricted trigonometric graphs over the line , emphasizing how input limitations prevent outputs outside the real numbers and enforce one-to-one mappings. The principal branches ensure the functions are strictly monotonic—either increasing or decreasing—within their domains, with horizontal asymptotes for and highlighting their behavior at infinity, unlike the bounded ranges of the other inverses.[12] The following table summarizes the domains and principal ranges for the six inverse trigonometric functions, underscoring that and are uniquely defined over all reals, in contrast to the bounded or exterior domains of the others:| Function | Domain | Principal Range |

|---|---|---|

![{\displaystyle [-1,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51e3b7f14a6f70e614728c583409a0b9a8b9de01)

![{\displaystyle \left[-{\tfrac {\pi }{2}},{\tfrac {\pi }{2}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2052f9d4a9c6a14f6db2e4bcd2606bce26d720d)

![{\displaystyle [0,\pi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e2a912eda6ef1afe46a81b518fe9da64a832751)

![{\displaystyle [\,0,\;\pi \,]\;\;\;\setminus \left\{{\tfrac {\pi }{2}}\right\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c913c2c78d11f57ccd118976bfb4b0595e5a2e0e)

![{\displaystyle \left[-{\tfrac {\pi }{2}},{\tfrac {\pi }{2}}\right]\setminus \{0\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e84fda7925743a03ffa0aec3fbed76a2967a3012)

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} \setminus (-1,1)=(-\infty ,-1]\cup [1,\infty )}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/105fc2887189c9dbf0d165542a768dcd97f03069)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin \theta &=-\sin(-\theta )&&=-\sin(\pi +\theta )&&={\phantom {-}}\sin(\pi -\theta )\\&=-\cos \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\cos \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&=-\cos \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)\\&={\phantom {-}}\cos \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&=-\cos \left({\frac {3\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&=-\cos \left(-{\frac {3\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)\\[0.3ex]\cos \theta &={\phantom {-}}\cos(-\theta )&&=-\cos(\pi +\theta )&&=-\cos(\pi -\theta )\\&={\phantom {-}}\sin \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\sin \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&=-\sin \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)\\&=-\sin \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&=-\sin \left({\frac {3\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\sin \left(-{\frac {3\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)\\[0.3ex]\tan \theta &=-\tan(-\theta )&&={\phantom {-}}\tan(\pi +\theta )&&=-\tan(\pi -\theta )\\&=-\cot \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\cot \left({\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\cot \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)\\&=-\cot \left(-{\frac {\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)&&={\phantom {-}}\cot \left({\frac {3\pi }{2}}-\theta \right)&&=-\cot \left(-{\frac {3\pi }{2}}+\theta \right)\\[0.3ex]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/316baee0254e64a99779ac4721054f23295aeec6)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\arccos(x)&={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\arcsin(x)\\[0.5em]\operatorname {arccot} (x)&={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\arctan(x)\\[0.5em]\operatorname {arccsc} (x)&={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\operatorname {arcsec} (x)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ec43798232f580abb074cf15f3d77692edd36af0)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\arcsin \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\operatorname {arccsc} (x)&\\[0.3em]\operatorname {arccsc} \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\arcsin(x)&\\[0.3em]\arccos \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\operatorname {arcsec} (x)&\\[0.3em]\operatorname {arcsec} \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\arccos(x)&\\[0.3em]\arctan \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\operatorname {arccot} (x)&={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\arctan(x)\,,{\text{ if }}x>0\\[0.3em]\arctan \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\operatorname {arccot} (x)-\pi &=-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-\arctan(x)\,,{\text{ if }}x<0\\[0.3em]\operatorname {arccot} \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\arctan(x)&={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\operatorname {arccot} (x)\,,{\text{ if }}x>0\\[0.3em]\operatorname {arccot} \left({\frac {1}{x}}\right)&=\arctan(x)+\pi &={\frac {3\pi }{2}}-\operatorname {arccot} (x)\,,{\text{ if }}x<0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2fca7d530f42c84ed92b5895ccbafb013dc6645)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\arcsin(x)&=2\arctan \left({\frac {x}{1+{\sqrt {1-x^{2}}}}}\right)\\[0.5em]\arccos(x)&=2\arctan \left({\frac {\sqrt {1-x^{2}}}{1+x}}\right)\,,{\text{ if }}-1<x\leq 1\\[0.5em]\arctan(x)&=2\arctan \left({\frac {x}{1+{\sqrt {1+x^{2}}}}}\right)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7dd6a9370a877ca5e198e28b7582bd06b377bdc3)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\arcsin(z)&=z+\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right){\frac {z^{3}}{3}}+\left({\frac {1\cdot 3}{2\cdot 4}}\right){\frac {z^{5}}{5}}+\left({\frac {1\cdot 3\cdot 5}{2\cdot 4\cdot 6}}\right){\frac {z^{7}}{7}}+\cdots \\[5pt]&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}}{\frac {z^{2n+1}}{2n+1}}\\[5pt]&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(2n)!}{(2^{n}n!)^{2}}}{\frac {z^{2n+1}}{2n+1}}\,;\qquad |z|\leq 1\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a0f778db7f760db059cf12f13ee5c2bf239fbb2f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int \arcsin(z)\,dz&{}=z\,\arcsin(z)+{\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}+C\\\int \arccos(z)\,dz&{}=z\,\arccos(z)-{\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}+C\\\int \arctan(z)\,dz&{}=z\,\arctan(z)-{\frac {1}{2}}\ln \left(1+z^{2}\right)+C\\\int \operatorname {arccot} (z)\,dz&{}=z\,\operatorname {arccot} (z)+{\frac {1}{2}}\ln \left(1+z^{2}\right)+C\\\int \operatorname {arcsec} (z)\,dz&{}=z\,\operatorname {arcsec} (z)-\ln \left[z\left(1+{\sqrt {\frac {z^{2}-1}{z^{2}}}}\right)\right]+C\\\int \operatorname {arccsc} (z)\,dz&{}=z\,\operatorname {arccsc} (z)+\ln \left[z\left(1+{\sqrt {\frac {z^{2}-1}{z^{2}}}}\right)\right]+C\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e3e2dde92bb82231c4326e45ce8b50e7298688bb)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\arcsin(z)&{}=-i\ln \left({\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}+iz\right)=i\ln \left({\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}-iz\right)&{}=\operatorname {arccsc} \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\\[10pt]\arccos(z)&{}=-i\ln \left(i{\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}+z\right)={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\arcsin(z)&{}=\operatorname {arcsec} \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\\[10pt]\arctan(z)&{}=-{\frac {i}{2}}\ln \left({\frac {i-z}{i+z}}\right)=-{\frac {i}{2}}\ln \left({\frac {1+iz}{1-iz}}\right)&{}=\operatorname {arccot} \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\\[10pt]\operatorname {arccot} (z)&{}=-{\frac {i}{2}}\ln \left({\frac {z+i}{z-i}}\right)=-{\frac {i}{2}}\ln \left({\frac {iz-1}{iz+1}}\right)&{}=\arctan \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\\[10pt]\operatorname {arcsec} (z)&{}=-i\ln \left(i{\sqrt {1-{\frac {1}{z^{2}}}}}+{\frac {1}{z}}\right)={\frac {\pi }{2}}-\operatorname {arccsc} (z)&{}=\arccos \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\\[10pt]\operatorname {arccsc} (z)&{}=-i\ln \left({\sqrt {1-{\frac {1}{z^{2}}}}}+{\frac {i}{z}}\right)=i\ln \left({\sqrt {1-{\frac {1}{z^{2}}}}}-{\frac {i}{z}}\right)&{}=\arcsin \left({\frac {1}{z}}\right)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/13b511be341b52fcd0c0660f3a4b1e5a164bfcb1)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {Im} \left(\ln z\right)\in (-\pi ,\pi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/781cef7f2317c18794eeaaddeef4073aadd51b75)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}z&={\frac {e^{i\phi }-e^{-i\phi }}{2i}}\\[10mu]2iz&=\xi -{\frac {1}{\xi }}\\[5mu]0&=\xi ^{2}-2iz\xi -1\\[5mu]\xi &=iz\pm {\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}\\[5mu]\phi &=-i\ln \left(iz\pm {\sqrt {1-z^{2}}}\right)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed03e8cf773fa44cc78823d65f7d82f41276fb96)