Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Versine

View on Wikipedia| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

| Reference |

| Laws and theorems |

| Calculus |

| Mathematicians |

The versine or versed sine is a trigonometric function found in some of the earliest (Sanskrit Aryabhatia,[1] Section I) trigonometric tables. The versine of an angle is 1 minus its cosine.

There are several related functions, most notably the coversine and haversine. The latter, half a versine, is of particular importance in the haversine formula of navigation.

Overview

[edit]The versine[3][4][5][6][7] or versed sine[8][9][10][11][12] is a trigonometric function already appearing in some of the earliest trigonometric tables. It is symbolized in formulas using the abbreviations versin, sinver,[13][14] vers, or siv.[15][16] In Latin, it is known as the sinus versus (flipped sine), versinus, versus, or sagitta (arrow).[17]

Expressed in terms of common trigonometric functions sine, cosine, and tangent, the versine is equal to

There are several related functions corresponding to the versine:

- The versed cosine,[18][nb 1] or vercosine, abbreviated vercosin, vercos, or vcs

- The coversed sine or coversine[19] (in Latin, cosinus versus or coversinus), abbreviated coversin, covers,[20][21][22] cosiv, or cvs[23]

Special tables were also made of half of the versed sine, because of its particular use in the haversine formula used historically in navigation.

- The haversed sine[24] or haversine (Latin semiversus),[25][26] abbreviated haversin, semiversin, semiversinus, havers, hav,[27][28] hvs,[nb 2] sem, or hv.[29] It is defined as

History and applications

[edit]Versine and coversine

[edit]

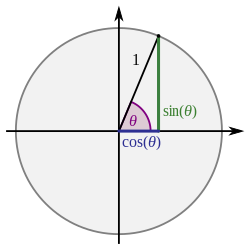

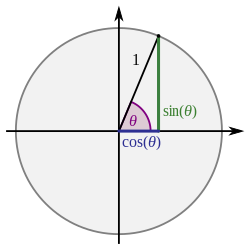

The ordinary sine function (see note on etymology) was sometimes historically called the sinus rectus ("straight sine"), to contrast it with the versed sine (sinus versus).[31] The meaning of these terms is apparent if one looks at the functions in the original context for their definition, a unit circle:

For a vertical chord AB of the unit circle, the sine of the angle θ (representing half of the subtended angle Δ) is the distance AC (half of the chord). On the other hand, the versed sine of θ is the distance CD from the center of the chord to the center of the arc. Thus, the sum of cos(θ) (equal to the length of line OC) and versin(θ) (equal to the length of line CD) is the radius OD (with length 1). Illustrated this way, the sine is vertical (rectus, literally "straight") while the versine is horizontal (versus, literally "turned against, out-of-place"); both are distances from C to the circle.

This figure also illustrates the reason why the versine was sometimes called the sagitta, Latin for arrow.[17][30] If the arc ADB of the double-angle Δ = 2θ is viewed as a "bow" and the chord AB as its "string", then the versine CD is clearly the "arrow shaft".

In further keeping with the interpretation of the sine as "vertical" and the versed sine as "horizontal", sagitta is also an obsolete synonym for the abscissa (the horizontal axis of a graph).[30]

In 1821, Cauchy used the terms sinus versus (siv) for the versine and cosinus versus (cosiv) for the coversine.[15][16][nb 1]

As θ goes to zero, versin(θ) is the difference between two nearly equal quantities, so a user of a trigonometric table for the cosine alone would need a very high accuracy to obtain the versine in order to avoid catastrophic cancellation, making separate tables for the latter convenient.[12] Even with a calculator or computer, round-off errors make it advisable to use the sin2 formula for small θ.

Another historical advantage of the versine is that it is always non-negative, so its logarithm is defined everywhere except for the single angle (θ = 0, 2π, …) where it is zero—thus, one could use logarithmic tables for multiplications in formulas involving versines.

In fact, the earliest surviving table of sine (half-chord) values (as opposed to the chords tabulated by Ptolemy and other Greek authors), calculated from the Surya Siddhantha of India dated back to the 3rd century BC, was a table of values for the sine and versed sine (in 3.75° increments from 0 to 90°).[31]

The versine appears as an intermediate step in the application of the half-angle formula sin2(θ/2) = 1/2versin(θ), derived by Ptolemy, that was used to construct such tables.

Haversine

[edit]The haversine, in particular, was important in navigation because it appears in the haversine formula, which is used to reasonably accurately compute distances on an astronomic spheroid (see issues with the Earth's radius vs. sphere) given angular positions (e.g., longitude and latitude). One could also use sin2(θ/2) directly, but having a table of the haversine removed the need to compute squares and square roots.[12]

An early utilization by José de Mendoza y Ríos of what later would be called haversines is documented in 1801.[14][32]

The first known English equivalent to a table of haversines was published by James Andrew in 1805, under the name "Squares of Natural Semi-Chords".[33][34][17]

In 1835, the term haversine (notated naturally as hav. or base-10 logarithmically as log. haversine or log. havers.) was coined[35] by James Inman[14][36][37] in the third edition of his work Navigation and Nautical Astronomy: For the Use of British Seamen to simplify the calculation of distances between two points on the surface of the Earth using spherical trigonometry for applications in navigation.[3][35] Inman also used the terms nat. versine and nat. vers. for versines.[3]

Other high-regarded tables of haversines were those of Richard Farley in 1856[33][38] and John Caulfield Hannyngton in 1876.[33][39]

The haversine continues to be used in navigation and has found new applications in recent decades, as in Bruce D. Stark's method for clearing lunar distances utilizing Gaussian logarithms since 1995[40][41] or in a more compact method for sight reduction since 2014.[29]

Modern uses

[edit]While the usage of the versine, coversine and haversine as well as their inverse functions can be traced back centuries, the names for the other five cofunctions appear to be of much younger origin.

One period (0 < θ < 2π) of a versine or, more commonly, a haversine waveform is also commonly used in signal processing and control theory as the shape of a pulse or a window function (including Hann, Hann–Poisson and Tukey windows), because it smoothly (continuous in value and slope) "turns on" from zero to one (for haversine) and back to zero.[nb 2] In these applications, it is named Hann function or raised-cosine filter.

Mathematical identities

[edit]Definitions

[edit]| [4] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [4] |

|

Circular rotations

[edit]The functions are circular rotations of each other.

Derivatives and integrals

[edit]| [42] | [4][42] |

| [19] | [19] |

| [24] | [24] |

Inverse functions

[edit]Inverse functions like arcversine (arcversin, arcvers,[8] avers,[43][44] aver), arcvercosine (arcvercosin, arcvercos, avercos, avcs), arccoversine (arccoversin, arccovers,[8] acovers,[43][44] acvs), arccovercosine (arccovercosin, arccovercos, acovercos, acvc), archaversine (archaversin, archav, haversin−1,[45] invhav,[46][47][48] ahav,[43][44] ahvs, ahv, hav−1[49][50]), archavercosine (archavercosin, archavercos, ahvc), archacoversine (archacoversin, ahcv) or archacovercosine (archacovercosin, archacovercos, ahcc) exist as well:

| [43][44] |

| [43][44] |

| [43][44][45][46][47][49][50] |

Other properties

[edit]These functions can be extended into the complex plane.[42][19][24]

Approximations

[edit]

When the versine v is small in comparison to the radius r, it may be approximated from the half-chord length L (the distance AC shown above) by the formula[51]

Alternatively, if the versine is small and the versine, radius, and half-chord length are known, they may be used to estimate the arc length s (AD in the figure above) by the formula This formula was known to the Chinese mathematician Shen Kuo, and a more accurate formula also involving the sagitta was developed two centuries later by Guo Shoujing.[52]

A more accurate approximation used in engineering[53] is

Arbitrary curves and chords

[edit]The term versine is also sometimes used to describe deviations from straightness in an arbitrary planar curve, of which the above circle is a special case. Given a chord between two points in a curve, the perpendicular distance v from the chord to the curve (usually at the chord midpoint) is called a versine measurement. For a straight line, the versine of any chord is zero, so this measurement characterizes the straightness of the curve. In the limit as the chord length L goes to zero, the ratio 8v/L2 goes to the instantaneous curvature. This usage is especially common in rail transport, where it describes measurements of the straightness of the rail tracks[54] and it is the basis of the Hallade method for rail surveying.

The term sagitta (often abbreviated sag) is used similarly in optics, for describing the surfaces of lenses and mirrors.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Some English sources confuse the versed cosine with the coversed sine. Historically (f.e. in Cauchy, 1821), the sinus versus (versine) was defined as siv(θ) = 1−cos(θ), the cosinus versus (what is now also known as coversine) as cosiv(θ) = 1−sin(θ), and the vercosine as vcsθ = 1+cos(θ). However, in their 2009 English translation of Cauchy's work, Bradley and Sandifer associate the cosinus versus (and cosiv) with the versed cosine (what is now also known as vercosine) rather than the coversed sine. Similarly, in their 1968/2000 work, Korn and Korn associate the covers(θ) function with the versed cosine instead of the coversed sine.

- ^ a b The abbreviation hvs sometimes used for the haversine function in signal processing and filtering is also sometimes used for the unrelated Heaviside step function.

References

[edit]- ^ The Āryabhaṭīya by Āryabhaṭa

- ^ Haslett, Charles (September 1855). Hackley, Charles W. (ed.). The Mechanic's, Machinist's, Engineer's Practical Book of Reference: Containing tables and formulæ for use in superficial and solid mensuration; strength and weight of materials; mechanics; machinery; hydraulics, hydrodynamics; marine engines, chemistry; and miscellaneous recipes. Adapted to and for the use of all classes of practical mechanics. Together with the Engineer's Field Book: Containing formulæ for the various of running and changing lines, locating side tracks and switches, &c., &c. Tables of radii and their logarithms, natural and logarithmic versed sines and external secants, natural sines and tangents to every degree and minute of the quadrant, and logarithms from the natural numbers from 1 to 10,000. New York, USA: James G. Gregory, successor of W. A. Townsend & Co. (Stringer & Townsend). Retrieved 2017-08-13.

[…] Still there would be much labor of computation which may be saved by the use of tables of external secants and versed sines, which have been employed with great success recently by the Engineers on the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad, and which, with the formulas and rules necessary for their application to the laying down of curves, drawn up by Mr. Haslett, one of the Engineers of that Road, are now for the first time given to the public. […] In presenting this work to the public, the Author claims for it the adaptation of a new principle in trigonometrical analysis of the formulas generally used in field calculations. Experience has shown, that versed sines and external secants as frequently enter into calculations on curves as sines and tangents; and by their use, as illustrated in the examples given in this work, it is believed that many of the rules in general use are much simplified, and many calculations concerning curves and running lines made less intricate, and results obtained with more accuracy and far less trouble, than by any methods laid down in works of this kind. The examples given have all been suggested by actual practice, and will explain themselves. […] As a book for practical use in field work, it is confidently believed that this is more direct in the application of rules and facility of calculation than any work now in use. In addition to the tables generally found in books of this kind, the author has prepared, with great labor, a Table of Natural and Logarithmic Versed Sines and External Secants, calculated to degrees, for every minute; also, a Table of Radii and their Logarithms, from 1° to 60°. […]

1856 edition - ^ a b c Inman, James (1835) [1821]. Navigation and Nautical Astronomy: For the Use of British Seamen (3 ed.). London, UK: W. Woodward, C. & J. Rivington. Retrieved 2015-11-09. (Fourth edition: [1].)

- ^ a b c d e Zucker, Ruth (1983) [June 1964]. "Chapter 4.3.147: Elementary Transcendental Functions - Circular functions". In Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann (eds.). Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. Vol. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. LCCN 64-60036. MR 0167642. LCCN 65-12253.

- ^ Tapson, Frank (2004). "Background Notes on Measures: Angles". 1.4. Cleave Books. Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ^ Oldham, Keith B.; Myland, Jan C.; Spanier, Jerome (2009) [1987]. "32.13. The Cosine cos(x) and Sine sin(x) functions - Cognate functions". An Atlas of Functions: with Equator, the Atlas Function Calculator (2 ed.). Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p. 322. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-48807-3. ISBN 978-0-387-48806-6. LCCN 2008937525.

- ^ Beebe, Nelson H. F. (2017-08-22). "Chapter 11.1. Sine and cosine properties". The Mathematical-Function Computation Handbook - Programming Using the MathCW Portable Software Library (1 ed.). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 301. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64110-2. ISBN 978-3-319-64109-6. LCCN 2017947446. S2CID 30244721.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, Arthur Graham; Frink, Fred Goodrich (January 1909). "Review Exercises [100] Secondary Trigonometric Functions". Written at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Trigonometry. Vol. Part I: Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: Henry Holt and Company / Norwood Press / J. S. Cushing Co. - Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Massachusetts, USA. pp. 125–127. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ Boyer, Carl Benjamin (1969) [1959]. "5: Commentary on the Paper of E. J. Dijksterhuis (The Origins of Classical Mechanics from Aristotle to Newton)". In Clagett, Marshall (ed.). Critical Problems in the History of Science (3 ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press, Ltd. pp. 185–190. ISBN 0-299-01874-1. LCCN 59-5304. 9780299018740. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Swanson, Todd; Andersen, Janet; Keeley, Robert (1999). "5 (Trigonometric Functions)" (PDF). Precalculus: A Study of Functions and Their Applications. Harcourt Brace & Company. p. 344. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-06-17. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ^ Korn, Grandino Arthur; Korn, Theresa M. (2000) [1961]. "Appendix B: B9. Plane and Spherical Trigonometry: Formulas Expressed in Terms of the Haversine Function". Mathematical handbook for scientists and engineers: Definitions, theorems, and formulars for reference and review (3 ed.). Mineola, New York, USA: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 892–893. ISBN 978-0-486-41147-7. (See errata.)

- ^ a b c Calvert, James B. (2007-09-14) [2004-01-10]. "Trigonometry". Archived from the original on 2007-10-02. Retrieved 2015-11-08.

- ^ Edler von Braunmühl, Anton (1903). Vorlesungen über Geschichte der Trigonometrie - Von der Erfindung der Logarithmen bis auf die Gegenwart [Lectures on history of trigonometry - from the invention of logarithms up to the present] (in German). Vol. 2. Leipzig, Germany: B. G. Teubner. p. 231. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ a b c Cajori, Florian (1952) [March 1929]. A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2 (2 (3rd corrected printing of 1929 issue) ed.). Chicago, USA: Open court publishing company. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-60206-714-1. 1602067147. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

The haversine first appears in the tables of logarithmic versines of José de Mendoza y Rios (Madrid, 1801, also 1805, 1809), and later in a treatise on navigation of James Inman (1821). See J. D. White in Nautical Magazine (February and July 1926).

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (NB. ISBN and link for reprint of 2nd edition by Cosimo, Inc., New York, USA, 2013.) - ^ a b Cauchy, Augustin-Louis (1821). "Analyse Algébrique". Cours d'Analyse de l'Ecole royale polytechnique (in French). Vol. 1. L'Imprimerie Royale, Debure frères, Libraires du Roi et de la Bibliothèque du Roi.access-date=2015-11-07--> (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00208-0)

- ^ a b Bradley, Robert E.; Sandifer, Charles Edward (2010-01-14) [2009]. Buchwald, J. Z. (ed.). Cauchy's Cours d'analyse: An Annotated Translation. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Cauchy, Augustin-Louis. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. pp. 10, 285. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0549-9. ISBN 978-1-4419-0548-2. LCCN 2009932254. 1441905499, 978-1-4419-0549-9. Retrieved 2015-11-09. (See errata.)

- ^ a b c d van Brummelen, Glen Robert (2013). Heavenly Mathematics: The Forgotten Art of Spherical Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691148922. 0691148929. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Vercosine". MathWorld. Wolfram Research, Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-03-24. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ a b c d Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Coversine". MathWorld. Wolfram Research, Inc. Archived from the original on 2005-11-27. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ Ludlow, Henry Hunt; Bass, Edgar Wales (1891). Elements of Trigonometry with Logarithmic and Other Tables (3 ed.). Boston, USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 33. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Wentworth, George Albert (1903) [1887]. Plane Trigonometry (2 ed.). Boston, USA: Ginn and Company. p. 5.

- ^ Kenyon, Alfred Monroe; Ingold, Louis (1913). Trigonometry. New York, USA: The Macmillan Company. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Anderegg, Frederick; Roe, Edward Drake (1896). Trigonometry: For Schools and Colleges. Boston, USA: Ginn and Company. p. 10. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ a b c d e Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Haversine". MathWorld. Wolfram Research, Inc. Archived from the original on 2005-03-10. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ Fulst, Otto (1972). "17, 18". In Lütjen, Johannes; Stein, Walter; Zwiebler, Gerhard (eds.). Nautische Tafeln (in German) (24 ed.). Bremen, Germany: Arthur Geist Verlag.

- ^ Sauer, Frank (2015) [2004]. "Semiversus-Verfahren: Logarithmische Berechnung der Höhe" (in German). Hotheim am Taunus, Germany: Astrosail. Archived from the original on 2013-09-17. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ^ Rider, Paul Reece; Davis, Alfred (1923). Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 42. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ "Haversine". Wolfram Language & System: Documentation Center. 7.0. 2008. Archived from the original on 2014-09-01. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ a b Rudzinski, Greg (July 2015). "Ultra compact sight reduction". Ocean Navigator (227). Ix, Hanno. Portland, ME, USA: Navigator Publishing LLC: 42–43. ISSN 0886-0149. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- ^ a b c "sagitta". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Boyer, Carl Benjamin; Merzbach, Uta C. (1991-03-06) [1968]. A History of Mathematics (2 ed.). New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471543978. 0471543977. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ de Mendoza y Ríos, Joseph (1795). Memoria sobre algunos métodos nuevos de calcular la longitud por las distancias lunares: y aplicación de su teórica á la solucion de otros problemas de navegacion (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Imprenta Real.

- ^ a b c Archibald, Raymond Clare (1945). "Recent Mathematical Tables : 197[C, D].—Natural and Logarithmic Haversines..." Mathematical Tables and Other Aids to Computation. 1 (11): 421–422. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-45-99080-6.

- ^ Andrew, James (1805). Astronomical and Nautical Tables with Precepts for finding the Latitude and Longitude of Places. Vol. T. XIII. London. pp. 29–148. (A 7-place haversine table from 0° to 120° in intervals of 10".)

- ^ a b "haversine". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ White, J. D. (February 1926). "(unknown title)". Nautical Magazine. (NB. According to Cajori, 1929, this journal has a discussion on the origin of haversines.)

- ^ White, J. D. (July 1926). "(unknown title)". Nautical Magazine. (NB. According to Cajori, 1929, this journal has a discussion on the origin of haversines.)

- ^ Farley, Richard (1856). Natural Versed Sines from 0 to 125°, and Logarithmic Versed Sines from 0 to 135°. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (A haversine table from 0° to 125°/135°.) - ^ Hannyngton, John Caulfield (1876). Haversines, Natural and Logarithmic, used in Computing Lunar Distances for the Nautical Almanac. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (A 7-place haversine table from 0° to 180°, log. haversines at intervals of 15", nat. haversines at intervals of 10".) - ^ Stark, Bruce D. (1997) [1995]. Stark Tables for Clearing the Lunar Distance and Finding Universal Time by Sextant Observation Including a Convenient Way to Sharpen Celestial Navigation Skills While On Land (2 ed.). Starpath Publications. ISBN 978-0914025214. 091402521X. Retrieved 2015-12-02. (NB. Contains a table of Gaussian logarithms lg(1+10−x).)

- ^ Kalivoda, Jan (2003-07-30). "Bruce Stark - Tables for Clearing the Lunar Distance and Finding G.M.T. by Sextant Observation (1995, 1997)" (Review). Prague, Czech Republic. Archived from the original on 2004-01-12. Retrieved 2015-12-02.[2][3]

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Versine". MathWorld. Wolfram Research, Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f Simpson, David G. (2001-11-08). "AUXTRIG" (Fortran 90 source code). Greenbelt, Maryland, USA: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ a b c d e f van den Doel, Kees (2010-01-25). "jass.utils Class Fmath". JASS - Java Audio Synthesis System. 1.25. Archived from the original on 2007-09-02. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ a b mf344 (2014-07-04). "Lost but lovely: The haversine". Plus magazine. maths.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Skvarc, Jure (1999-03-01). "identify.py: An asteroid_server client which identifies measurements in MPC format". Fitsblink (Python source code). Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ^ a b Skvarc, Jure (2014-10-27). "astrotrig.py: Astronomical trigonometry related functions" (Python source code). Ljubljana, Slovenia: Telescope Vega, University of Ljubljana. Archived from the original on 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ^ Ballew, Pat (2007-02-08) [2003]. "Versine". Math Words, page 4. Versine. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Inverse Haversine". MathWorld. Wolfram Research, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ a b "InverseHaversine". Wolfram Language & System: Documentation Center. 7.0. 2008. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ^ Woodward, Ernest (December 1978). Geometry - Plane, Solid & Analytic Problem Solver. Problem Solvers Solution Guides. Research & Education Association (REA). p. 359. ISBN 978-0-87891-510-1.

- ^ Needham, Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery (1959). Science and Civilisation in China: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780521058018.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Boardman, Harry (1930). Table For Use in Computing Arcs, Chords and Versines. Chicago Bridge and Iron Company. p. 32.

- ^ Nair, P. N. Bhaskaran (1972). "Track measurement systems—concepts and techniques". Rail International. 3 (3). International Railway Congress Association, International Union of Railways: 159–166. ISSN 0020-8442. OCLC 751627806.

Further reading

[edit]- Hawking, Stephen W., ed. (2002). On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 0-7624-1698-X.

- Miller, Jeff. "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (V)". In O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (eds.). MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2025-05-05.

External links

[edit]Versine

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition

The versine, also known as the versed sine, is a trigonometric function defined mathematically as , where is an angle in radians.[4] This function originates from the geometric interpretation in a unit circle, where it represents the sagitta—the perpendicular distance from the midpoint of a chord subtended by the arc of central angle to the midpoint of the arc itself.[5] Geometrically, in a unit circle with the arc from to , the sagitta measures , capturing the deviation from the chord to the arc. Equivalently, for an arc of angle from the positive x-axis to , the versine corresponds to the length along the diameter from the initial point to the foot of the perpendicular from the endpoint to the diameter, which is .[6] The versine exhibits several basic properties inherent to its definition. It is an even function, satisfying , because the cosine is even. Additionally, it is periodic with period , as , mirroring the periodicity of the cosine. The range of the versine is the closed interval , since the cosine varies between and $11 - \cos(\theta) nonnegative and bounded above by $2.[4][7] Visually, in a unit circle diagram, the versine can be illustrated by drawing a chord connecting the endpoints of the arc subtended by from the positive x-axis; the sagitta is then the line segment from the chord's midpoint to the circle's arc at its midpoint, emphasizing the function's role in describing circular deviations. A related function is the coversine, defined as , which provides a complementary geometric measure analogous to the versine but aligned with the sine, representing the sagitta in a configuration rotated by .[4] The haversine, briefly, is half the versine.[8]Relation to Other Trigonometric Functions

The versine function is fundamentally linked to the cosine through its primary definition: versin(θ) = 1 - cos(θ). This relation stems from the geometric interpretation of the versine as the length of the versed chord in a unit circle. Equivalently, using the half-angle formula for cosine, which rearranges to 1 - cos(θ) = 2 sin²(θ/2), the versine can be expressed as versin(θ) = 2 sin²(θ/2).[9] This identity highlights the versine's connection to the sine function via half-angles, facilitating computations in certain trigonometric contexts. The coversine function complements the versine, defined as coversin(θ) = 1 - sin(θ). It relates directly to the versine through the complementary angle identity: coversin(θ) = versin(π/2 - θ).[10] This equivalence arises because cos(π/2 - θ) = sin(θ), so 1 - cos(π/2 - θ) = 1 - sin(θ). Together, versine and coversine form a pair analogous to sine and cosine, emphasizing their roles in complementary trigonometric pairs. Versine belongs to a broader class of chord functions in historical trigonometry, which includes the exsecant, defined as exsec(θ) = sec(θ) - 1 = 1/cos(θ) - 1, and the excosecant, excsc(θ) = csc(θ) - 1 = 1/sin(θ) - 1.[11][12] These functions, like the versine, measure excesses over unity in reciprocal trigonometric ratios, often appearing in early tables for chord length calculations. To illustrate these relations, the following table compares the values of sine, cosine, versine, and coversine for selected angles in the interval [0, π], computed using standard trigonometric definitions (values rounded to four decimal places for clarity):| θ (radians) | sin(θ) | cos(θ) | versin(θ) = 1 - cos(θ) | coversin(θ) = 1 - sin(θ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| π/6 | 0.5000 | 0.8660 | 0.1340 | 0.5000 |

| π/3 | 0.8660 | 0.5000 | 0.5000 | 0.1340 |

| π/2 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 2π/3 | 0.8660 | -0.5000 | 1.5000 | 0.1340 |

| 5π/6 | 0.5000 | -0.8660 | 1.8660 | 0.5000 |

| π | 0.0000 | -1.0000 | 2.0000 | 1.0000 |

Historical Context

Origins in Ancient Astronomy

The versine, known as utkrama-jya in Sanskrit, first emerged in ancient Indian astronomy as a key trigonometric tool for chord calculations essential to modeling celestial motions. In Aryabhata's Āryabhaṭīya, composed around 499 CE, the function is defined and applied within the context of a sine table, where it represents the versed sine (R - R cos θ, with radius R typically 3438 units) to facilitate computations of planetary positions and arcs on the celestial sphere.[13][14] This innovation built on earlier chord-based methods, enabling more precise determinations of angular distances in astronomical tables divided into 225-minute intervals.[14] Possible precursors to the versine appear in Greek astronomy through chord tables, which approximated arc lengths for celestial calculations. Ptolemy's Almagest, from the 2nd century CE, features a comprehensive table of chords subtending angles from 0.5° to 180° in a circle of radius 60 parts, used to derive positions of stars, planets, and the sun by converting angular measures to linear distances in right triangles.[15] These chords, equivalent to twice the sine of half-angles, laid foundational geometric techniques that influenced later developments, including the versine's role in sagitta approximations for small arcs.[15] In medieval Islamic astronomy, the versine concept was adopted and refined through translations and syntheses of Indian and Greek works. Al-Battani (c. 858–929 CE), in his Kitāb al-Zīj, integrated trigonometric tables—including sines and related functions derived from chord methods—to enhance the accuracy of planetary ephemerides and solar-lunar motions beyond Ptolemy's values.[16] His observations over four decades produced refined zij tables that employed these functions for computing eccentricities and anomalies in the celestial sphere.[16][17] Around 980 CE, Abul Wafa explored trigonometric identities related to the versine, further advancing its application in astronomical computations.[2] By the 14th century, the versine was integrated into European mathematics by Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson in his De Sinibus, Chordis et Arcubus, where it was used to derive precise sine and chord values at 15-minute intervals for solar and planetary motion calculations.[3] European adoption continued in the 16th century with Regiomontanus's trigonometric tables, which included versine values, though it gradually faded from mainstream use with the rise of logarithmic sine and cosine functions by the 17th century.[1] Prior to the dominance of sine and cosine in modern trigonometry, the versine proved invaluable for estimating distances and elevations on the celestial sphere, particularly in eclipse predictions and visibility calculations.[14] This astronomical utility later extended to navigational applications in subsequent centuries.Development in Navigation

The haversine function, defined as hav(θ) = versin(θ)/2, emerged as a practical tool in navigation during the Renaissance, building on earlier uses of the versine in spherical trigonometry. Scottish mathematician James Gregory employed the versed sine (versin(θ) = 1 - cos(θ)) in his 1670s work on geometric and trigonometric series, providing foundational methods for calculating arcs and angles relevant to astronomical observations at sea.[18] This laid groundwork for more specialized functions in maritime computations. Tobias Mayer further advanced its application in the 1750s through his precise lunar tables, which facilitated the lunar distance method for determining longitude. Mayer's tables, submitted to the British Board of Longitude in 1755 and later incorporated into the Nautical Almanac starting in 1767, relied on spherical trigonometric identities involving the versine to clear observed angular distances between the Moon and fixed stars, enabling navigators to compute time differences with errors reduced to under half a degree.[19] The haversine played a pivotal role in great-circle navigation, allowing computation of the shortest path between two points on Earth's surface. The key formula is hav(Δσ) = hav(Δφ) + hav(Δλ) cos(φ₁) cos(φ₂), where Δσ is the angular distance, Δφ the difference in latitudes, and Δλ the difference in longitudes at latitudes φ₁ and φ₂; this equation avoids singularities in logarithmic tables and minimizes rounding errors during manual calculations.[20] In the 19th century, haversine tables were published to streamline these computations, with early versions appearing in works by José de Mendoza y Ríos in 1801 and James Andrew in 1805. By the 1830s, such tables were integrated into nautical almanacs, including the British Nautical Almanac, where the term "haversine" was formalized by James Inman in his 1835 Navigation. These tables, providing haversine values to high precision, significantly reduced computational errors in great-circle sailing and sight reductions, often cutting calculation time by half compared to cosine-based methods.[21] The reliance on haversine declined after the 1970s with the widespread adoption of electronic calculators and computers, which favored direct cosine-rule implementations for spherical distances due to their simplicity in programming. Nonetheless, the haversine's legacy persists in foundational navigation formulas and modern geospatial software.[20]Core Mathematical Properties

Fundamental Identities

The versine function, defined as , satisfies a fundamental half-angle identity that relates it directly to the sine function: This identity arises from the half-angle formula for cosine, , rearranged accordingly.[9][22] The haversine is defined as half the versine: .[9] For double angles, the versine can be expressed using the double-angle formula for cosine, , which yields Substituting provides a reduction solely in terms of the versine: This relation facilitates power reduction and simplification in expressions involving even multiples of angles.[22][23]Differentiation and Integration

The derivative of the versine function is This result follows from the relation , as the derivative of the constant 1 is 0 and the derivative of is .[9] Using the chain rule, the derivative of a composite versine function is . For instance, if for constant , then . This property simplifies computations in contexts involving scaled angles, such as in periodic phenomena.[9] The second derivative is obtained by differentiating . Higher-order derivatives cycle through , , and , mirroring the derivatives of the cosine function but offset by one differentiation.[9] The indefinite integral of the versine function is derived by integrating term by term, yielding minus the integral of , which is .[9] For a definite integral example, consider . The integral of the versine function relates to the parametric equations of the cycloid, where the vertical coordinate is for radius , linking the function's antiderivative to the curve's horizontal progression .[24]Advanced Relations and Approximations

Rotational and Inverse Properties

The versine function demonstrates rotational symmetry through its periodicity, satisfying versin(θ + 2π) = versin(θ) for all real θ, a direct consequence of the 2π-periodicity of the cosine function from which it is defined as versin(θ) = 1 - cos(θ).[25][26] This periodicity reflects the circular nature of the underlying trigonometric relation, allowing the function to repeat identically after a full rotation. Additionally, the versine exhibits reflection symmetries consistent with its even nature and periodic structure. Specifically, versin(-θ) = versin(θ), making it an even function symmetric about the y-axis, and versin(2π - θ) = versin(θ), providing symmetry about θ = π.[26] These properties arise from the even symmetry of cosine and its behavior under reflection across the unit circle. For rotations by an arbitrary angle α, the versine can be expanded using addition formulas derived from the cosine sum identity: versin(θ + α) = 1 - cos(θ + α) = 1 - [cos θ cos α - sin θ sin α] = versin(θ) cos α + sin θ sin α + versin(α).[26] This expression highlights how versine combines with sine and cosine terms under angular shifts, though full derivations rely on standard trigonometric expansions. The inverse versine, denoted arversin(x) or versin⁻¹(x), is defined as the angle θ such that versin(θ) = x, equivalently θ = arccos(1 - x), with domain x ∈ [0, 2] corresponding to the range of versin over [0, π].[27] Graphically, arversin(x) is a strictly increasing function from (0, 0) to (2, π), concave down, mirroring the shape of the versine curve inverted over the line y = x in the principal branch; its derivative, where defined, follows from the chain rule applied to the arccosine relation.[27] To solve the equation versin(θ) = k for k ∈ [0, 2], the general solution accounts for the function's evenness and periodicity: θ = 2πn ± arversin(k), where n ∈ ℤ. This multi-valued nature yields infinitely many solutions spaced by 2π, with pairs symmetric about multiples of π due to the reflection properties.[27]Approximation Formulas

The Taylor series expansion for the versine function, centered at θ = 0, is derived from the corresponding series for the cosine function. Specifically, versin(θ) = ∑{n=1}^∞ (-1)^{n+1} θ^{2n} / (2n)!, which begins as versin(θ) = θ²/2! - θ⁴/4! + θ⁶/6! - θ⁸/8! + ⋯.[28] This even-powered series arises because versin(θ) = 1 - cos(θ), and subtracting the cosine series (cos(θ) = ∑{n=0}^∞ (-1)^n θ^{2n} / (2n)!) yields the form above, with the constant term canceling out.[29] For small angles θ (in radians), the leading term provides a useful approximation: versin(θ) ≈ θ²/2. This follows directly from truncating the Taylor series after the first term, as higher-order terms become negligible when |θ| ≪ 1. The absolute error in this approximation is bounded by the remainder term, approximately θ⁴/24 for small θ, leading to a relative error on the order of θ²/12.[9] This approximation is particularly valuable in computations where θ is small, avoiding numerical cancellation issues inherent in evaluating 1 - cos(θ) directly.[30] The haversine function, defined as hav(θ) = versin(θ)/2 = sin²(θ/2), shares a similar small-angle behavior and is prominent in navigational applications. For small θ, hav(θ) ≈ (θ/2)², derived from the small-angle approximation sin(φ) ≈ φ with φ = θ/2. This quadratic form simplifies distance calculations on spheres, such as great-circle distances, where the central angle θ is often small for nearby points.[30] The versine series offers advantages in convergence for certain arc-related computations, particularly near θ = 0, compared to the cosine or sine series, due to its avoidance of subtractive cancellation and focus on even powers starting quadratically. The table below compares the first few terms of the versine, cosine, and sine series (all in radians, centered at 0) to illustrate the structural differences:| Function | Series Expansion (first four nonzero terms) |

|---|---|

| versin(θ) | θ²/2 - θ⁴/24 + θ⁶/720 - θ⁸/40320 |

| cos(θ) | 1 - θ²/2 + θ⁴/24 - θ⁶/720 |

| sin(θ) | θ - θ³/6 + θ⁵/120 - θ⁷/5040 |

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\operatorname {versin} (\theta )+\operatorname {coversin} (\theta )}{\operatorname {versin} (\theta )-\operatorname {coversin} (\theta )}}-{\frac {\operatorname {exsec} (\theta )+\operatorname {excsc} (\theta )}{\operatorname {exsec} (\theta )-\operatorname {excsc} (\theta )}}&={\frac {2\operatorname {versin} (\theta )\operatorname {coversin} (\theta )}{\operatorname {versin} (\theta )-\operatorname {coversin} (\theta )}}\\[3pt][\operatorname {versin} (\theta )+\operatorname {exsec} (\theta )]\,[\operatorname {coversin} (\theta )+\operatorname {excsc} (\theta )]&=\sin(\theta )\cos(\theta )\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2309ac826855590e363f4f4e8372c556ac165e3e)