Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isenthalpic process

View on WikipediaThis article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (October 2025) |

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

An isenthalpic process or isoenthalpic process is a process that proceeds without any change in enthalpy, H; or specific enthalpy, h.[1]

If a steady-state, steady-flow process is analysed using a control volume, everything outside the control volume is considered to be the surroundings.[2]

Definition and formula

[edit]Such a process will be isenthalpic if there is no transfer of heat to or from the surroundings, no work done on or by the surroundings, and no change in the kinetic energy of the fluid.[3] This is a sufficient but not necessary condition for isoenthalpy. The necessary condition for a process to be isoenthalpic is that the sum of each of the terms of the energy balance other than enthalpy (work, heat, changes in kinetic energy, etc.) cancel each other, so that the enthalpy remains unchanged. For a process in which magnetic and electric effects (among others) give negligible contributions, the associated energy balance can be written as

If then it must be that

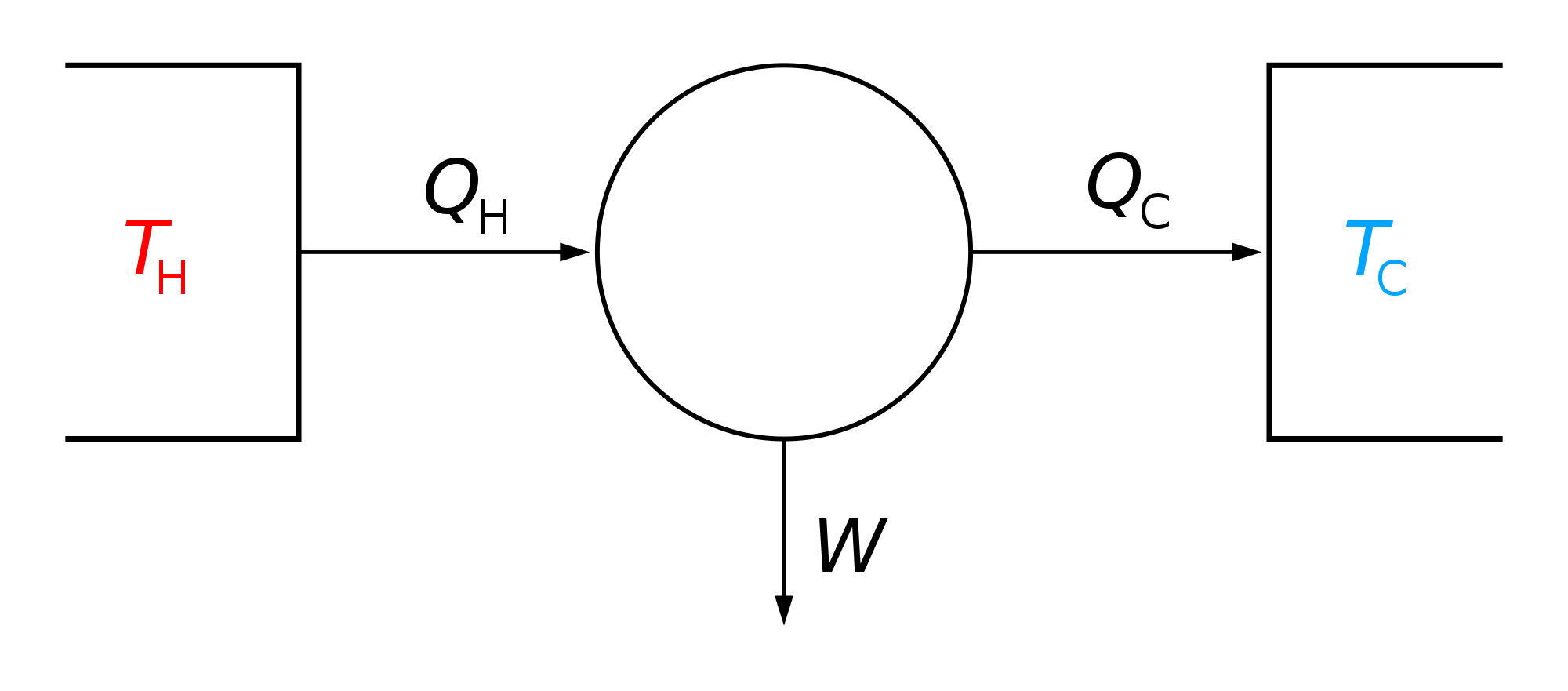

Where K is kinetic energy, u is internal energy, Q is heat, W is work, h is enthalpy, P is pressure, and V is volume.

Example

[edit]The throttling process is a good example of an isoenthalpic process in which significant changes in pressure and temperature can occur to the fluid, and yet the net sum of the associated terms in the energy balance is null, thus rendering the transformation isoenthalpic. The lifting of a relief (or safety) valve on a pressure vessel is an example of throttling process. The specific enthalpy of the fluid inside the pressure vessel is the same as the specific enthalpy of the fluid as it escapes through the valve.[3] With a knowledge of the specific enthalpy of the fluid and the pressure outside the pressure vessel, it is possible to determine the temperature and speed of the escaping fluid.

In an isenthalpic process:

- ,

- .

Isenthalpic processes on an ideal gas follow isotherms, since .

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- G. J. Van Wylen and R. E. Sonntag (1985), Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York ISBN 0-471-82933-1

Notes

[edit]- ^ Atkins, Peter; Julio de Paula (2006). Atkin's Physical Chemistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-870072-2.

- ^ G. J. Van Wylen and R. E. Sonntag, Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, Section 2.1 (3rd edition).

- ^ a b G. J. Van Wylen and R. E. Sonntag, Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, Section 5.13 (3rd edition).

Isenthalpic process

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

An isenthalpic process is a thermodynamic process in which the enthalpy of the system remains constant, denoted as , irrespective of variations in pressure, volume, or temperature.[1] This constancy implies that the total heat content at constant pressure does not change, distinguishing it from other processes like isobaric or isothermal ones where different properties are held invariant.[3] Enthalpy, , is defined as the sum of the internal energy of the system and the product of pressure and volume , expressed as .[5] This formulation is particularly significant in open systems or flow processes, where enthalpy accounts for both the internal energy transported by the fluid and the flow work associated with pressure-volume interactions across system boundaries.[6] The term "isenthalpic" originates from the Greek prefix "iso-" meaning "equal" combined with "enthalpy," a word derived from "en-" (in) and "thalpein" (to heat), reflecting its relation to heat content.[7] First recorded in 1925 in scientific literature, it was formalized in early 20th-century thermodynamics building on 19th-century foundational concepts, though synonymous phrases like "constant enthalpy process" are also used interchangeably in technical contexts.[8]Thermodynamic Context

In the context of open thermodynamic systems, the isenthalpic process derives from the first law of thermodynamics applied to steady-state flow conditions, where the differential change in enthalpy satisfies dh = δq + v dP for specific quantities, with δq representing heat transfer per unit mass and v dP the flow work term.[9] This relation highlights how constant enthalpy (dh = 0) implies a balance where any heat addition is offset by pressure-volume work, often resulting in negligible net heat transfer in practical scenarios. Enthalpy itself, defined as H = U + PV, naturally emerges in open-system analyses to account for both internal energy and the energy associated with fluid flow across system boundaries.[9] Isenthalpic processes are particularly applicable to steady-state flow in engineering devices like valves, where mass flow rates are constant and changes in kinetic or potential energy are negligible, leading to the steady-flow energy equation simplifying to h_1 = h_2 under adiabatic conditions with no shaft work.[10] These processes typically occur in control volumes where fluid expands through restrictions, maintaining overall energy conservation without external work input beyond flow work.[11] Such processes are inherently irreversible due to dissipative effects like friction and turbulent mixing, rather than proceeding reversibly, and they assume no heat transfer (δq = 0), which aligns with adiabatic but non-quasistatic conditions where entropy increases.[10] The ideality relies on neglecting kinetic energy variations and assuming uniform properties, though real implementations often involve minor deviations from perfect steadiness.[11] In single-phase systems, isenthalpic processes maintain uniform composition, potentially leading to temperature shifts via intermolecular forces, as seen in real gases.[10] Conversely, in multiphase systems, the process can accommodate phase transitions—such as vaporization or condensation—while preserving total enthalpy, enabling equilibrium calculations across liquid-vapor boundaries without net enthalpy alteration.[12] This behavior is critical for systems where phase separation occurs under constant enthalpy constraints.[13]Mathematical Formulation

Enthalpy Conservation

In an isenthalpic process, the specific enthalpy remains constant between the initial and final states, expressed as or equivalently , where subscripts 1 and 2 denote the upstream and downstream conditions, respectively.[14] This conservation arises in steady-flow scenarios, such as fluid expansion through a restriction, where no heat transfer or shaft work occurs. The derivation follows from the first law of thermodynamics applied to a control volume under steady-flow conditions. The steady-flow energy equation states that for a unit mass of fluid, , where is heat transfer per unit mass, is work per unit mass, is velocity, and is elevation.[15] For an adiabatic throttling process (), with no shaft work () and negligible changes in kinetic and potential energy (), the equation simplifies to .[16] This form incorporates the flow work term into the enthalpy definition , where is specific internal energy, ensuring the energy balance holds without explicit accounting for boundary work. Enthalpy is a thermodynamic state function, depending solely on the system's state variables (such as temperature and pressure) rather than the process path.[14] Consequently, the change is path-independent, allowing isenthalpic processes to be represented as constant-enthalpy contours on diagrams like the enthalpy-entropy (H-S, or Mollier) chart or pressure-enthalpy (P-H) diagram, regardless of the specific trajectory from state 1 to state 2.[16] To determine properties in real-gas isenthalpic processes, thermodynamic tables or Mollier diagrams are employed. Starting from known initial conditions (), the final state () is located by tracing the constant-enthalpy line on the Mollier diagram, yielding values such as the final temperature .[17] These tools account for non-ideal behavior, providing accurate interpolations for fluids like steam or refrigerants where equation-of-state data are tabulated.Process Characteristics

In an isenthalpic process, the temperature behavior varies distinctly between ideal and real gases due to differences in their thermodynamic properties. For an ideal gas, enthalpy is a function solely of temperature, so maintaining constant enthalpy implies no change in temperature, making the process effectively isothermal.[18] In contrast, real gases exhibit temperature changes arising from intermolecular forces during pressure reduction; cooling occurs via the Joule-Thomson effect when the initial temperature is below the inversion temperature, while heating predominates above it.[19] These deviations stem from attractive and repulsive interactions that alter the internal energy balance without heat transfer or work. Isenthalpic processes are always irreversible, leading to a positive change in entropy (ΔS > 0) that signifies increased molecular disorder. This entropy generation arises from dissipative mechanisms, such as viscous friction and turbulent mixing, inherent to the process dynamics.[20] The irreversibility ensures that the system's available energy decreases, even as total enthalpy remains conserved. Regarding pressure and volume, an isenthalpic process typically involves a substantial pressure drop, with a corresponding increase in specific volume for gases, driven by the relation H = U + pV under constant enthalpy. Unlike controlled expansions that produce work, no net work is performed or extracted, resulting in purely dissipative energy redistribution.[3]Practical Applications

Throttling and Expansion

Throttling refers to an irreversible expansion process in which a fluid undergoes a sudden pressure drop as it passes through a restriction, such as a porous plug or valve, while maintaining constant enthalpy due to the absence of heat transfer and work input.[21] This process occurs under steady-flow conditions, where the upstream pressure exceeds the downstream pressure, leading to a non-equilibrium expansion characterized by frictional dissipation within the fluid.[22] Common devices that facilitate throttling include capillary tubes, orifice plates, and safety valves in pipelines. Capillary tubes, typically narrow copper passages, restrict flow to achieve precise pressure reduction in compact systems.[23] Orifice plates, thin barriers with a central hole inserted into pipelines, create a controlled pressure drop for flow measurement or regulation.[23] Safety valves, designed for emergency pressure relief, open abruptly to allow fluid discharge, exemplifying throttling in high-pressure industrial applications.[24] In nuclear engineering, throttling is used for pressure regulation in steam systems, helping maintain enthalpy balance to predict downstream states like temperature and phase from known upstream conditions and outlet pressure.[3] The energy balance in a throttling process derives from the steady-flow energy equation for a control volume, where there is no shaft work and negligible heat transfer, resulting in the conservation of stagnation enthalpy: , with denoting velocity.[21] In typical setups, kinetic energy changes are small compared to enthalpy, approximating the process as isenthalpic (), with energy dissipation occurring through viscous friction and turbulence, converting mechanical energy into internal energy without net temperature change for ideal gases.[21] This irreversibility manifests as entropy generation due to the uncontrolled expansion. Experimental verification of enthalpy constancy in throttling employs the porous plug apparatus, a setup originally developed to study real gas behavior. In this device, a tube is divided by a porous plug, and gas is forced at constant mass flow rate from a high-pressure upstream chamber (pressure , volume ) to a low-pressure downstream chamber (pressure , volume ).[22] Pistons maintain steady pressures, performing work on the system, while adiabatic insulation ensures no heat exchange. Measurements of internal energy changes balance against this work, confirming that enthalpy remains invariant across the plug.[22]Refrigeration and Cryogenics

In vapor-compression refrigeration systems, the throttling valve serves as the key component for the isenthalpic expansion of the refrigerant, where high-pressure liquid refrigerant is depressurized to evaporator pressure, resulting in partial evaporation and a significant temperature drop that enables heat absorption from the cooled space.[25] This process maintains constant enthalpy across the valve, transforming the refrigerant into a low-temperature liquid-vapor mixture that enters the evaporator at a reduced temperature, typically achieving cooling effects suitable for household or commercial applications.[26] The simplicity of this adiabatic, irreversible expansion makes it integral to standard refrigeration cycles, where the refrigerant, such as R-134a, undergoes flashing that cools the mixture by typically 40–70 K depending on operating pressures and system conditions.[27][28] In cryogenic liquefaction, the Linde process employs repeated isenthalpic throttling through Joule-Thomson valves to separate and liquefy air components, cooling compressed air streams to temperatures below -140°C by exploiting intermolecular forces in real gases during expansion.[29] Developed by Carl von Linde in 1895, this method compresses air to around 60 bar, precools it via heat exchange, and throttles it across a valve, where the temperature drop—approximately 0.25°C per bar—leads to partial liquefaction, with non-condensable gases recycled for further cooling in a countercurrent exchanger.[30] Repeated cycles in modern air separation units achieve cryogenic temperatures below -100°C, enabling efficient production of oxygen and nitrogen for industrial use.[31] Isenthalpic throttling is favored for its mechanical simplicity and lack of moving parts, but it is less efficient than isentropic expansion due to inherent irreversibilities that generate entropy and reduce the coefficient of performance (COP) in refrigeration cycles.[10] In vapor-compression systems, throttling losses account for a significant portion of total cycle inefficiencies, often lowering COP by 10-20% compared to expander-based alternatives, as the process does not recover expansion work and results in higher compressor input requirements.[32] Despite these drawbacks, its robustness and low cost justify its use in most practical systems, where COP values typically range from 2-4 for common refrigerants, prioritizing reliability over maximal efficiency.[33] In modern liquefied natural gas (LNG) production, isenthalpic throttling via Joule-Thomson valves is applied in small-scale plants to liquefy natural gas at -159°C to -162°C, offering a cost-effective alternative to complex turbo-expanders for on-site facilities like fueling stations.[34] For superconducting systems, 21st-century advancements in micro-throttling Joule-Thomson cryocoolers have enabled compact, vibration-free cooling to below 80 K for space applications, such as infrared detectors on satellites.[35] These developments, including open-cycle designs tested since 2010, enhance efficiency through optimized heat exchangers and throttling geometries, supporting missions like the Planck telescope while minimizing mass and power needs, with micromachined orifices achieving cooling powers of around 10 W at liquid nitrogen temperatures.[36]Related Phenomena

Joule-Thomson Effect

The Joule-Thomson effect refers to the temperature change observed in a real gas during an isenthalpic throttling process, where the gas expands through a porous plug or valve without heat transfer or work done. This deviation from ideal gas behavior arises due to intermolecular forces, leading to either cooling or heating depending on the conditions. The effect is quantified by the Joule-Thomson coefficient, defined as , which measures the rate of temperature change with pressure at constant enthalpy. The phenomenon was discovered through experiments conducted by James Prescott Joule and William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) between 1852 and 1862, where they observed a temperature drop in air expanding from high to low pressure through a throttle. Their work, initially reported in 1852 to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, demonstrated that real gases cool upon expansion under typical conditions, contrasting with the zero temperature change for ideal gases. Modern measurements confirm these findings, with detailed data for various gases including helium, which exhibits anomalous heating at room temperature due to its negative .[37] The Joule-Thomson coefficient can be derived thermodynamically using the chain rule and Maxwell relations, yielding , where is the heat capacity at constant pressure, is temperature, is volume, and the partial derivative reflects the thermal expansion coefficient. For ideal gases, , making ; however, in real gases, deviations stem from intermolecular attractions and repulsions modeled by equations like the van der Waals equation, where the attractive term contributes to cooling by hindering molecular separation. This linkage to van der Waals forces explains why is positive (cooling) for most gases at room temperature and moderate pressures. The inversion curve represents the locus of points in the pressure-temperature plane where , demarcating regions of cooling () from heating (). Above the inversion temperature, the gas heats upon expansion, while below it, cooling occurs. For carbon dioxide, the maximum inversion temperature is approximately 1500 K, allowing significant cooling under ambient conditions relevant to industrial processes.[38]Comparisons with Other Processes

An isenthalpic process, characterized by constant enthalpy (ΔH = 0), differs fundamentally from an isentropic process, which maintains constant entropy (ΔS = 0) and is both adiabatic and reversible. In an isenthalpic process, entropy increases (ΔS > 0) due to its irreversible nature, resulting in no net work output, whereas an isentropic process enables maximum work extraction, such as in ideal turbines or compressors. This contrast highlights the efficiency loss in isenthalpic expansions, where irreversibilities like friction or sudden pressure drops prevent reversible energy conversion.[39][40] For ideal gases, an isenthalpic process coincides with an isothermal process because enthalpy depends solely on temperature (H = C_p T), so ΔH = 0 implies ΔT = 0. However, for real gases, deviations arise due to intermolecular forces, leading to temperature changes via the Joule-Thomson effect, unlike purely isothermal processes that require heat transfer to maintain constant temperature. The table below compares key properties for a pressure reduction process in an ideal gas context:| Property | Isenthalpic Process | Isothermal Process |

|---|---|---|

| Enthalpy Change (ΔH) | 0 | 0 (for ideal gas) |

| Temperature Change (ΔT) | 0 (ideal gas) | 0 |

| Entropy Change (ΔS) | > 0 (irreversible) | ≥ 0 |

| Heat Transfer (Q) | 0 | = -W (to maintain T) |

| Work (W) | 0 | < 0 (expansion) |