Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isothermal process

View on Wikipedia| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

An isothermal process is a type of thermodynamic process in which the temperature T of a system remains constant: ΔT = 0. This typically occurs when a system is in contact with an outside thermal reservoir, and a change in the system occurs slowly enough to allow the system to be continuously adjusted to the temperature of the reservoir through heat exchange (see quasi-equilibrium). In contrast, an adiabatic process is where a system exchanges no heat with its surroundings (Q = 0).

Simply, we can say that in an isothermal process

- For ideal gases only, internal energy

while in adiabatic processes:

Etymology

[edit]The noun isotherm is derived from the Ancient Greek words ἴσος (ísos), meaning "equal", and θέρμη (thérmē), meaning "heat".

Examples

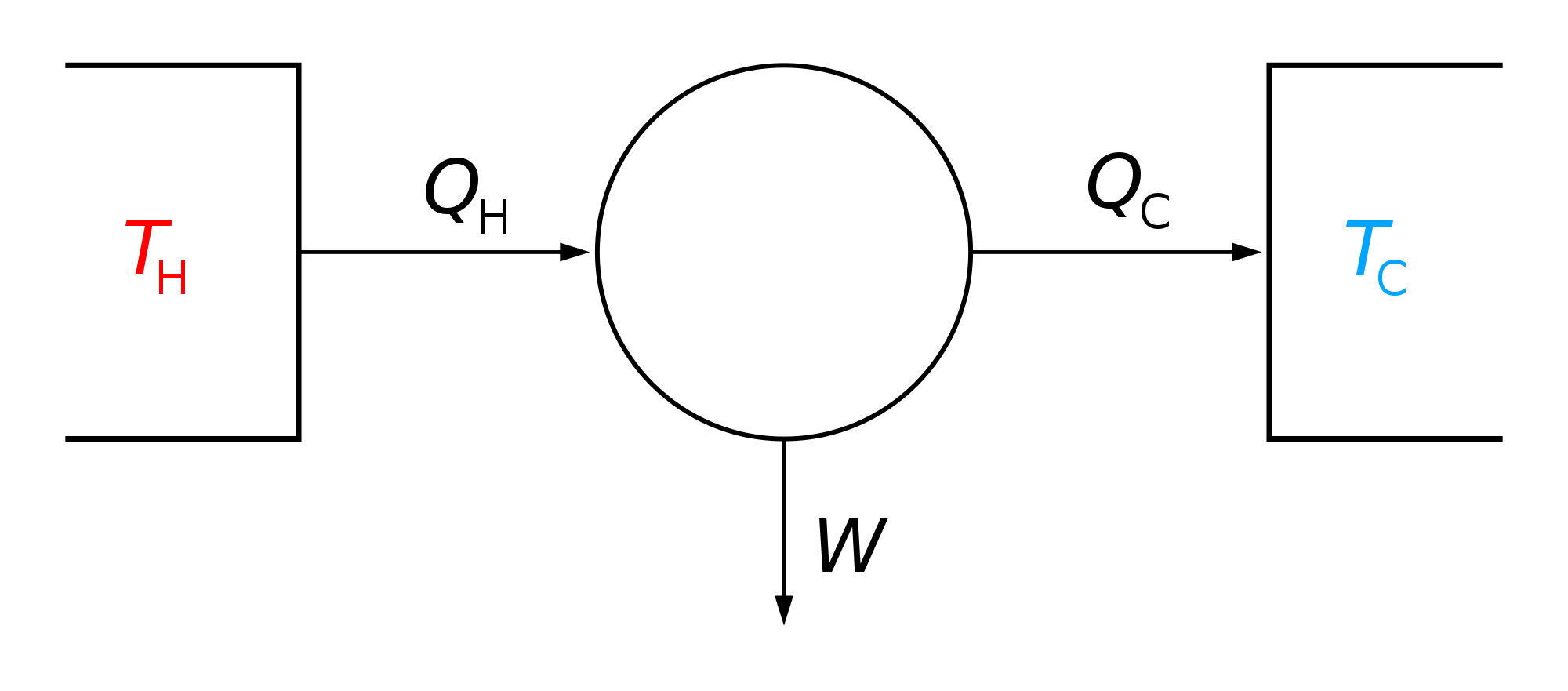

[edit]Isothermal processes can occur in any kind of system that has some means of regulating the temperature, including highly structured machines, and even living cells. Some parts of the cycles of some heat engines are carried out isothermally (for example, in the Carnot cycle).[1] In the thermodynamic analysis of chemical reactions, it is usual to first analyze what happens under isothermal conditions and then consider the effect of temperature.[2] Phase changes, such as melting or evaporation, are also isothermal processes when, as is usually the case, they occur at constant pressure.[3] Isothermal processes are often used as a starting point in analyzing more complex, non-isothermal processes.

Isothermal processes are of special interest for ideal gases. This is a consequence of Joule's second law which states that the internal energy of a fixed amount of an ideal gas depends only on its temperature.[4] Thus, in an isothermal process the internal energy of an ideal gas is constant. This is a result of the fact that in an ideal gas there are no intermolecular forces.[4] Note that this is true only for ideal gases; the internal energy depends on pressure as well as on temperature for liquids, solids, and real gases.[5]

In the isothermal compression of a gas there is work done on the system to decrease the volume and increase the pressure.[4] Doing work on the gas increases the internal energy and will tend to increase the temperature. To maintain the constant temperature energy must leave the system as heat and enter the environment. If the gas is ideal, the amount of energy entering the environment is equal to the work done on the gas, because internal energy does not change. For isothermal expansion, the energy supplied to the system does work on the surroundings. In either case, with the aid of a suitable linkage the change in gas volume can perform useful mechanical work. For details of the calculations, see calculation of work.

For an adiabatic process, in which no heat flows into or out of the gas because its container is well insulated, Q = 0. If there is also no work done, i.e. a free expansion, there is no change in internal energy. For an ideal gas, this means that the process is also isothermal.[4] Thus, specifying that a process is isothermal is not sufficient to specify a unique process.

Details for an ideal gas

[edit]

For the special case of a gas to which Boyle's law[4] applies, the product pV (p for gas pressure and V for gas volume) is a constant if the gas is kept at isothermal conditions. The value of the constant is nRT, where n is the number of moles of the present gas and R is the ideal gas constant. In other words, the ideal gas law pV = nRT applies.[4] Therefore:

holds. The family of curves generated by this equation is shown in the graph in Figure 1. Each curve is called an isotherm, meaning a curve at a same temperature T. Such graphs are termed indicator diagrams and were first used by James Watt and others to monitor the efficiency of engines. The temperature corresponding to each curve in the figure increases from the lower left to the upper right.

Calculation of work

[edit]

In thermodynamics, the reversible work involved when a gas changes from state A to state B is[6]

where p for gas pressure and V for gas volume. For an isothermal (constant temperature T), reversible process, this integral equals the area under the relevant PV (pressure-volume) isotherm, and is indicated in purple in Figure 2 for an ideal gas. Again, p = nRT/V applies and with T being constant (as this is an isothermal process), the expression for work becomes:

In IUPAC convention, work is defined as work on a system by its surroundings. If, for example, the system is compressed, then the work is done on the system by the surrounding so the work is positive and the internal energy of the system increases. Conversely, if the system expands (i.e., system surrounding expansion, so free expansions not the case), then the work is negative as the system does work on the surroundings.

It is also worth noting that for ideal gases, if the temperature is held constant, the internal energy of the system U also is constant, and so ΔU = 0. Since the first law of thermodynamics states that ΔU = Q + W in IUPAC convention, it follows that Q = −W for the isothermal compression or expansion of ideal gases.

Example of an isothermal process

[edit]

The reversible expansion of an ideal gas can be used as an example of work produced by an isothermal process. Of particular interest is the extent to which heat is converted to usable work, and the relationship between the confining force and the extent of expansion.

During isothermal expansion of an ideal gas, both p and V change along an isotherm with a constant pV product (i.e., constant T). Consider a working gas in a cylindrical chamber 1 m high and 1 m2 area (so 1m3 volume) at 400 K in static equilibrium. The surroundings consist of air at 300 K and 1 atm pressure (designated as psurr). The working gas is confined by a piston connected to a mechanical device that exerts a force sufficient to create a working gas pressure of 2 atm (state A). For any change in state A that causes a force decrease, the gas will expand and perform work on the surroundings. Isothermal expansion continues as long as the applied force decreases and appropriate heat is added to keep pV = 2 [atm·m3] (= 2 atm × 1 m3). The expansion is said to be internally reversible if the piston motion is sufficiently slow such that at each instant during the expansion the gas temperature and pressure is uniform and conform to the ideal gas law. Figure 3 shows the p–V relationship for pV = 2 [atm·m3] for isothermal expansion from 2 atm (state A) to 1 atm (state B).

The work done (designated ) has two components. First, expansion work against the surrounding atmosphere pressure (designated as WpΔV), and second, usable mechanical work (designated as Wmech). The output Wmech here could be movement of the piston used to turn a crank-arm, which would then turn a pulley capable of lifting water out of flooded salt mines.

The system attains state B (pV = 2 [atm·m3] with p = 1 atm and V = 2 m3) when the applied force reaches zero. At that point, equals –140.5 kJ, and WpΔV is –101.3 kJ. By difference, Wmech = –39.1 kJ, which is 27.9% of the heat supplied to the process (- 39.1 kJ / - 140.5 kJ). This is the maximum amount of usable mechanical work obtainable from the process at the stated conditions. The percentage of Wmech is a function of pV and psurr, and approaches 100% as psurr approaches zero.

To pursue the nature of isothermal expansion further, note the red line on Figure 3. The fixed value of pV causes an exponential increase in piston rise vs. pressure decrease. For example, a pressure decrease from 2 to 1.9 atm causes a piston rise of 0.0526 m. In comparison, a pressure decrease from 1.1 to 1 atm causes a piston rise of 0.1818 m.

Entropy changes

[edit]Isothermal processes are especially convenient for calculating changes in entropy since, in this case, the formula for the entropy change, ΔS, is simply

where Qrev is the heat transferred (internally reversible) to the system and T is absolute temperature.[7] This formula is valid only for a hypothetical reversible process; that is, a process in which equilibrium is maintained at all times.

A simple example is an equilibrium phase transition (such as melting or evaporation) taking place at constant temperature and pressure. For a phase transition at constant pressure, the heat transferred to the system is equal to the enthalpy of transformation, ΔHtr, thus Q = ΔHtr.[3] At any given pressure, there will be a transition temperature, Ttr, for which the two phases are in equilibrium (for example, the normal boiling point for vaporization of a liquid at one atmosphere pressure). If the transition takes place under such equilibrium conditions, the formula above may be used to directly calculate the entropy change[7]

- .

Another example is the reversible isothermal expansion (or compression) of an ideal gas from an initial volume VA and pressure PA to a final volume VB and pressure PB. As shown in Calculation of work, the heat transferred to the gas is

- .

This result is for a reversible process, so it may be substituted in the formula for the entropy change to obtain[7]

- .

Since an ideal gas obeys Boyle's law, this can be rewritten, if desired, as

- .

Once obtained, these formulas can be applied to an irreversible process, such as the free expansion of an ideal gas. Such an expansion is also isothermal and may have the same initial and final states as in the reversible expansion. Since entropy is a state function (that depends on an equilibrium state, not depending on a path that the system takes to reach that state), the change in entropy of the system is the same as in the reversible process and is given by the formulas above. Note that the result Q = 0 for the free expansion can not be used in the formula for the entropy change since the process is not reversible.

The difference between the reversible and irreversible is found in the entropy of the surroundings. In both cases, the surroundings are at a constant temperature, T, so that ΔSsur = −Q/T; the minus sign is used since the heat transferred to the surroundings is equal in magnitude and opposite in sign to the heat Q transferred to the system. In the reversible case, the change in entropy of the surroundings is equal and opposite to the change in the system, so the change in entropy of the universe is zero. In the irreversible, Q = 0, so the entropy of the surroundings does not change and the change in entropy of the universe is equal to ΔS for the system.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Keenan, J. H. (1970). "Chapter 12: Heat-engine cycles". Thermodynamics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ^ Rock, P. A. (1983). "Chapter 11: Thermodynamics of chemical reactions". Chemical Thermodynamics. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-12-1.

- ^ a b Petrucci, R. H.; Harwood, W. S.; Herring, F. G.; Madura, J. D. (2007). "Chapter 12". General Chemistry. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-149330-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Klotz, I. M.; Rosenberg, R. M. (1991). "Chapter 6, Application of the first law to gases". Chemical Thermodynamics. Meno Park, CA: Benjamin.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Adkins, C. J. (1983). Equilibrium Thermodynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Atkins, Peter (1997). "Chapter 2: The first law: the concepts". Physical Chemistry (6th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-2871-0.

- ^ a b c Atkins, Peter (1997). "Chapter 4: The second law: the concepts". Physical Chemistry (6th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-2871-0.