Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isentropic process

View on Wikipedia| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

An isentropic process is an idealized thermodynamic process that is both adiabatic and reversible.[1][2][3][4][5][6][excessive citations] In thermodynamics, adiabatic processes are reversible. Clausius (1875)[7] adopted "isentropic" as meaning the same as Rankine's word: "adiabatic". The work transfers of the system are frictionless, and there is no net transfer of heat or matter. Such an idealized process is useful in engineering as a model of and basis of comparison for real processes.[8] This process is idealized because reversible processes do not occur in reality; thinking of a process as both adiabatic and reversible would show that the initial and final entropies are the same, thus, the reason it is called isentropic (entropy does not change). Thermodynamic processes are named based on the effect they would have on the system (ex. isovolumetric/isochoric: constant volume, isenthalpic: constant enthalpy). Even though in reality it is not necessarily possible to carry out an isentropic process, some may be approximated as such.

The word "isentropic" derives from the process being one in which the entropy of the system remains unchanged, in addition to a process which is both adiabatic and reversible.

Background

[edit]The second law of thermodynamics states[9][10] that

where is the amount of energy the system gains by heating, is the temperature of the surroundings, and is the change in entropy. The equal sign refers to a reversible process, which is an imagined idealized theoretical limit, never actually occurring in physical reality, with essentially equal temperatures of system and surroundings.[11][12] For an isentropic process, if also reversible, there is no transfer of energy as heat because the process is adiabatic; δQ = 0. In contrast, if the process is irreversible, entropy is produced within the system; consequently, in order to maintain constant entropy within the system, energy must be simultaneously removed from the system as heat.

For reversible processes, an isentropic transformation is carried out by thermally "insulating" the system from its surroundings. Temperature is the thermodynamic conjugate variable to entropy, thus the conjugate process would be an isothermal process, in which the system is thermally "connected" to a constant-temperature heat bath.

Isentropic processes in thermodynamic systems

[edit]

The entropy of a given mass does not change during a process that is internally reversible and adiabatic. A process during which the entropy remains constant is called an isentropic process, written or .[13] Some examples of theoretically isentropic thermodynamic devices are pumps, gas compressors, turbines, nozzles, and diffusers.

Isentropic efficiencies of steady-flow devices in thermodynamic systems

[edit]Most steady-flow devices operate under adiabatic conditions, and the ideal process for these devices is the isentropic process. The parameter that describes how efficiently a device approximates a corresponding isentropic device is called isentropic or adiabatic efficiency.[13]

Isentropic efficiency of turbines:

Isentropic efficiency of compressors:

Isentropic efficiency of nozzles:

For all the above equations:

- is the specific enthalpy at the entrance state,

- is the specific enthalpy at the exit state for the actual process,

- is the specific enthalpy at the exit state for the isentropic process.

Isentropic devices in thermodynamic cycles

[edit]| Cycle | Isentropic step | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Rankine cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in a pump |

| Ideal Rankine cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion in a turbine |

| Ideal Carnot cycle | 2→3 | Isentropic expansion |

| Ideal Carnot cycle | 4→1 | Isentropic compression |

| Ideal Otto cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| Ideal Otto cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion |

| Ideal Diesel cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| Ideal Diesel cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion |

| Ideal Brayton cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in a compressor |

| Ideal Brayton cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion in a turbine |

| Ideal vapor-compression refrigeration cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in a compressor |

| Ideal Lenoir cycle | 2→3 | Isentropic expansion |

| Ideal Seiliger cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| Ideal Seiliger cycle | 4→5 | Isentropic compression |

Note: The isentropic assumptions are only applicable with ideal cycles. Real cycles have inherent losses due to compressor and turbine inefficiencies and the second law of thermodynamics. Real systems are not truly isentropic, but isentropic behavior is an adequate approximation for many calculation purposes.

Isentropic flow

[edit]In fluid dynamics, an isentropic flow is a fluid flow that is both adiabatic and reversible. That is, no heat is added to the flow, and no energy transformations occur due to friction or dissipative effects. For an isentropic flow of a perfect gas, several relations can be derived to define the pressure, density and temperature along a streamline.

Note that energy can be exchanged with the flow in an isentropic transformation, as long as it doesn't happen as heat exchange. An example of such an exchange would be an isentropic expansion or compression that entails work done on or by the flow.

For an isentropic flow, entropy density can vary between different streamlines. If the entropy density is the same everywhere, then the flow is said to be homentropic.

Derivation of the isentropic relations

[edit]For a closed system, the total change in energy of a system is the sum of the work done and the heat added:

The reversible work done on a system by changing the volume is

where is the pressure, and is the volume. The change in enthalpy () is given by

Then for a process that is both reversible and adiabatic (i.e. no heat transfer occurs), , and so All reversible adiabatic processes are isentropic. This leads to two important observations:

Next, a great deal can be computed for isentropic processes of an ideal gas. For any transformation of an ideal gas, it is always true that

- , and

Using the general results derived above for and , then

So for an ideal gas, the heat capacity ratio can be written as

For a calorically perfect gas is constant. Hence on integrating the above equation, assuming a calorically perfect gas, we get

that is,

Using the equation of state for an ideal gas, ,

(Proof: But nR = constant itself, so .)

also, for constant (per mole),

- and

Thus for isentropic processes with an ideal gas,

- or

Table of isentropic relations for an ideal gas

[edit]Derived from

where:

- = pressure,

- = volume,

- = ratio of specific heats = ,

- = temperature,

- = mass,

- = gas constant for the specific gas = ,

- = universal gas constant,

- = molecular weight of the specific gas,

- = density,

- = molar specific heat at constant pressure,

- = molar specific heat at constant volume.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Partington, J. R. (1949), An Advanced Treatise on Physical Chemistry., vol. 1, Fundamental Principles. The Properties of Gases, London: Longmans, Green and Co., p. 122.

- ^ Kestin, J. (1966). A Course in Thermodynamics, Blaisdell Publishing Company, Waltham MA, p. 196.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970). Classical Thermodynamics, translated by E. S. Halberstadt, Wiley–Interscience, London, ISBN 0-471-62430-6, p. 13.

- ^ Haase, R. (1971). Survey of Fundamental Laws, chapter 1 of Thermodynamics, pages 1–97 of volume 1, ed. W. Jost, of Physical Chemistry. An Advanced Treatise, ed. H. Eyring, D. Henderson, W. Jost, Academic Press, New York, lcn 73–117081, p. 71.

- ^ Borgnakke, C., Sonntag., R.E. (2009). Fundamentals of Thermodynamics, seventh edition, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-04192-5, p. 310.

- ^ Massey, B. S. (1970), Mechanics of Fluids, Section 12.2 (2nd edition) Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, London. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-25005, p. 19.

- ^ Clausius. "The Mechanical Theory of Heat" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Çengel, Y. A., Boles, M. A. (2015). Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 8th edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, ISBN 978-0-07-339817-4, p. 340.

- ^ Mortimer, R. G. Physical Chemistry, 3rd ed., p. 120, Academic Press, 2008.

- ^ Fermi, E. Thermodynamics, footnote on p. 48, Dover Publications,1956 (still in print).

- ^ Guggenheim, E. A. (1985). Thermodynamics. An Advanced Treatment for Chemists and Physicists, seventh edition, North Holland, Amsterdam, ISBN 0444869514, p. 12: "As a limiting case between natural and unnatural processes[,] we have reversible processes, which consist of the passage in either direction through a continuous series of equilibrium states. Reversible processes do not actually occur..."

- ^ Kestin, J. (1966). A Course in Thermodynamics, Blaisdell Publishing Company, Waltham MA, p. 127: "However, by a stretch of imagination, it was accepted that a process, compression or expansion, as desired, could be performed 'infinitely slowly'[,] or as is sometimes said, quasistatically." P. 130: "It is clear that all natural processes are irreversible and that reversible processes constitute convenient idealizations only."

- ^ a b Cengel, Yunus A., and Michaeul A. Boles. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach. 7th Edition ed. New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 2012. Print.

References

[edit]- Van Wylen, G. J. and Sonntag, R. E. (1965), Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19470

Isentropic process

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

An isentropic process is a thermodynamic process in which the entropy of the system remains constant, expressed as .[4] This constancy arises specifically from the combination of adiabatic conditions, where no heat transfer occurs (), and reversibility, which eliminates any irreversibilities such as friction, viscous dissipation, or finite pressure differences.[4] Unlike general adiabatic processes, which may involve entropy increases due to irreversibilities, isentropic processes represent an idealization requiring perfect insulation and infinitely slow, equilibrium-maintained execution.[5] The term "isentropic" derives from the Greek prefix "iso-" (meaning equal or constant) and "entropy," highlighting the unchanging nature of this thermodynamic property during the process.[6] Historically, the concept developed within classical thermodynamics in the 19th century, building on Rudolf Clausius's foundational work, where he introduced entropy in 1865 as to describe the transformation of heat into work and the directionality of natural processes.[7] Clausius's entropy formulation provided the basis for identifying processes like isentropic ones as reversible limits where no net entropy production occurs.[4] Key characteristics of an isentropic process include its quasi-static progression through infinite equilibrium stages, ensuring that the system remains in thermodynamic equilibrium at every point, which is essential for reversibility.[5] On a temperature-entropy (-) diagram, it appears as a vertical line, with temperature potentially changing while entropy holds steady, visually distinguishing it from other processes that slope due to entropy variations. Entropy itself, per Clausius, serves as a measure of the energy unavailable for useful work in a system, often linked to molecular disorder or the dispersal of energy.[7] In idealized examples, an isentropic process models the compression of a gas in a frictionless piston with perfect thermal insulation or the expansion of a working fluid in a turbine without heat loss, both approximating real-world scenarios under controlled, reversible conditions.[9]Thermodynamic Implications

In an isentropic process for a closed system, the first law of thermodynamics simplifies significantly because there is no heat transfer (Q = 0). The change in internal energy equals the work done on or by the system: ΔU = W. For a reversible isentropic process, this work is calculated as the integral of pressure with respect to volume, W = ∫ P dV, representing the maximum possible work exchange without dissipative losses.[10] The second law of thermodynamics further underscores the ideal nature of isentropic processes, where entropy generation is zero (dS_gen = 0), ensuring the process is both adiabatic and reversible. This contrasts with irreversible adiabatic processes, in which entropy increases (ΔS > 0) due to internal irreversibilities like friction or mixing. The absence of entropy production implies perfect reversibility, allowing the system to return to its initial state without net changes in entropy across cycles.[10] During an isentropic process, thermodynamic properties evolve predictably according to conservation principles. In expansion, both temperature and pressure decrease as the system performs work, converting internal energy into mechanical energy while maintaining constant entropy. Conversely, compression increases temperature and pressure, with the system absorbing work to raise its energy state. These changes reflect the interplay of energy conservation and the fixed entropy constraint, ensuring orderly transformations without disorder increase.[11] Isentropic processes are vividly represented on thermodynamic diagrams, aiding visualization of state changes. On a temperature-entropy (T-S) diagram, they appear as vertical lines, indicating constant entropy with varying temperature. In pressure-volume (P-V) diagrams, isentropic paths are steeper than isothermal curves, reflecting the P V^γ relation for ideal gases where γ > 1. For open systems or flows, the enthalpy-entropy (h-S) or Mollier diagram shows isentropic processes as vertical lines, useful for analyzing expansions in turbines or nozzles.[12][13][14] In practice, truly isentropic processes are unattainable due to inherent irreversibilities such as friction, heat leaks, or non-quasi-static changes, which generate entropy and reduce efficiency. Real processes approximate isentropics under controlled conditions, like in high-speed compressors or expanders, but always fall short. The isentropic ideal serves as a theoretical benchmark for evaluating the performance and efficiency of thermodynamic devices, quantifying losses through comparisons to this reversible limit.[11]Mathematical Formulation

Relations for Ideal Gases

For an isentropic process involving an ideal gas, the analysis assumes perfect gas behavior with constant specific heats at constant pressure () and constant volume (). The ratio of specific heats, denoted as , is a key parameter; for diatomic gases like air at standard conditions, .[15][16] Since entropy remains constant in an isentropic process, the following relations hold between pressure (), volume (), and temperature (): These equations apply to both closed systems and can be adapted for open systems under isentropic conditions.[17][15][16] In the context of compressible flow, the speed of sound () for an isentropic process in an ideal gas is given by where is the specific gas constant (or the universal gas constant divided by molar mass for molar forms). This relation underscores the dependence of acoustic propagation on temperature and the gas properties under reversible adiabatic conditions.[18] The relations can be formulated on a per-unit-mass basis using the specific gas constant (in J/kg·K) or for moles using the universal gas constant (in J/mol·K), with volume replaced by molar volume where appropriate. For instance, in molar terms, , ensuring consistency across thermodynamic analyses.[17][16]| Relation Type | Equation | Variables Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure-Volume | ||

| Temperature-Volume | ||

| Temperature-Pressure | ||

| Pressure-Temperature | ||

| Speed of Sound |

Derivation of Key Equations

The fundamental derivation of isentropic relations begins with the differential form of the second law of thermodynamics for a closed system, where the entropy change is zero: .[19] This expression arises from the combined first and second laws, , with for a substance where internal energy depends only on temperature, such as an ideal gas.[19] For an ideal gas, the ideal gas law (per mole) yields , substituting to give .[20] To integrate for an ideal gas, rearrange as . Assuming constant specific heats, where and , so , the equation becomes , or . Integrating both sides yields , or .[20] This relation can also be obtained via logarithmic differentiation of the entropy expression for an ideal gas, , where setting directly implies the constant form.[20] For a more general derivation applicable to open systems or steady-flow processes, consider the entropy differential in terms of temperature and pressure: .[21] This follows from the enthalpy-based form of the thermodynamic identity, , where for constant pressure processes.[19] For an ideal gas, , leading to , and integration gives .[21] These relations, including , , and , are known as Poisson's equations, historically derived by Siméon Denis Poisson in 1823 for reversible adiabatic processes in gases under the caloric theory. Poisson's work built on earlier ideas by Laplace, focusing on the integration of the adiabatic condition using the speed of sound and compressibility. These derivations assume reversibility, as requires no entropy generation from irreversibilities like friction or heat transfer across finite gradients. For non-ideal gases, the relations do not hold in simple power-law form; instead, thermodynamic property tables or equations of state must be used to evaluate changes along isentropic paths.[21]Applications in Systems

Steady-Flow Devices and Efficiencies

In steady-flow devices such as turbines, compressors, and nozzles, the isentropic process represents an ideal benchmark for adiabatic operations where entropy remains constant, allowing for the maximum possible work extraction or minimum input for a given pressure change.[22] These open systems operate under steady-state conditions, governed by the steady-flow energy equation, which for a control volume with negligible kinetic and potential energy changes simplifies to per unit mass, where is specific enthalpy, is heat transfer, and is work.[16] For adiabatic processes, , so the isentropic work output for a turbine or input for a compressor becomes , with subscript denoting the isentropic exit state.[22] Isentropic efficiency quantifies how closely a real device approaches this ideal by comparing actual performance to the isentropic case. For a turbine, it is defined as , representing the ratio of actual work output to the maximum possible under isentropic conditions.[16] For a compressor, the efficiency is , the ratio of isentropic work input to actual work input.[22] In nozzles, where the goal is to convert enthalpy to kinetic energy, the efficiency is , comparing actual exit kinetic energy to the isentropic value.[16] Enthalpy-entropy (h-s) diagrams are commonly used to visualize these efficiencies, plotting the ideal isentropic path as a vertical line of constant entropy alongside the actual path, which deviates to the right due to irreversibilities, highlighting enthalpy losses.[23] In real devices, factors such as fluid friction, shock waves, and minor heat leaks introduce entropy generation, preventing efficiencies from reaching 100%.[22] Typical values for well-designed modern turbines range from 70% to 90%, compressors from 75% to 85%, and nozzles from 90% to 98%, depending on design and operating conditions.[23] A practical example is the axial compressor in jet engines, which approximates isentropic compression across multiple stages to achieve high pressure ratios with efficiencies often exceeding 85%, minimizing energy losses in the compression process before combustion.[24]Thermodynamic Cycles

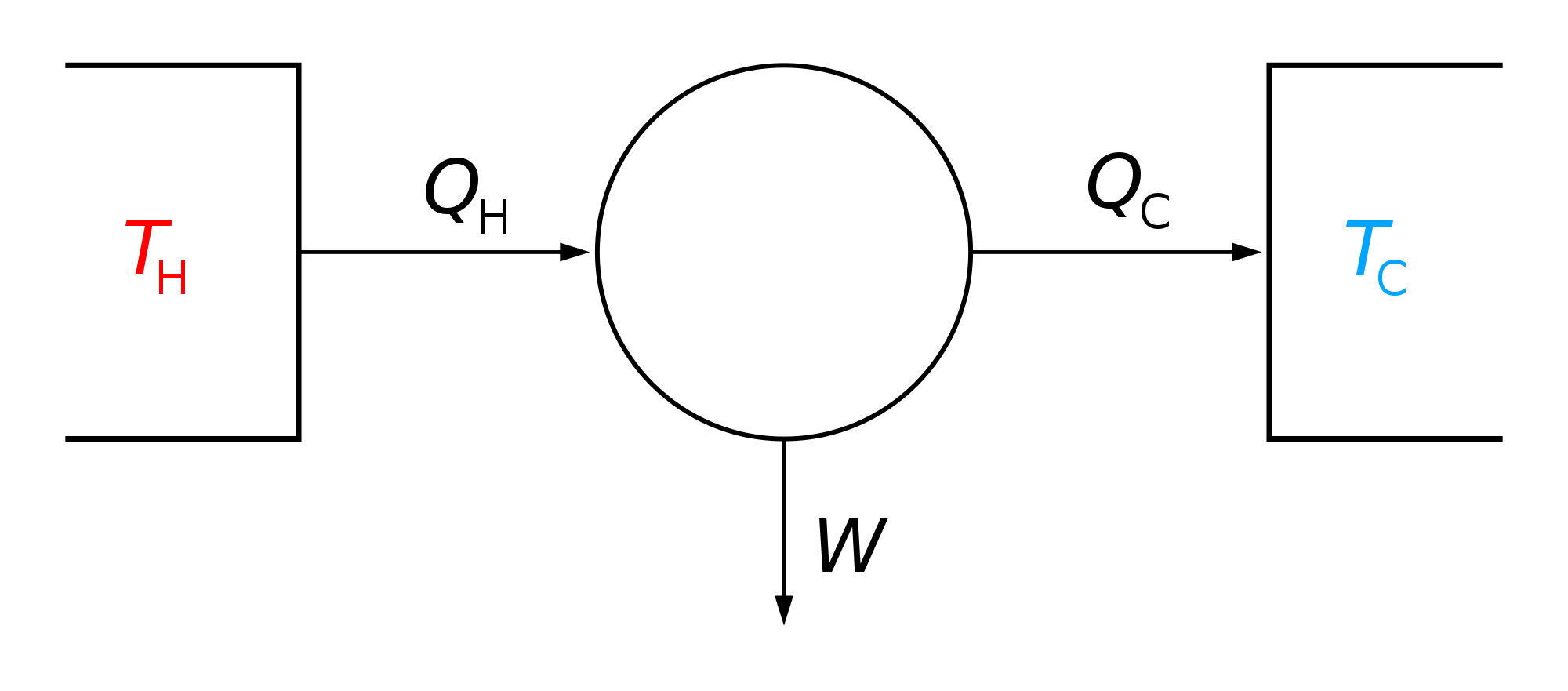

In thermodynamic cycles, isentropic processes serve as idealized building blocks that maximize efficiency by representing reversible adiabatic compression and expansion, thereby minimizing entropy generation and optimizing work output or input across the cycle. These legs ensure that no heat transfer occurs during compression or expansion, allowing the cycle to approach the theoretical limits set by the second law of thermodynamics.[25] The Otto cycle, which models spark-ignition reciprocating engines, incorporates two isentropic processes: compression from state 1 to 2 and expansion from state 3 to 4. During compression, the air-fuel mixture is adiabatically compressed to increase temperature and pressure, followed by constant-volume heat addition and then isentropic expansion to extract work. The thermal efficiency of the ideal Otto cycle is given by , where is the compression ratio () and is the specific heat ratio of the gas. This formula highlights how higher compression ratios enhance efficiency, but practical limitations such as engine knock—premature auto-ignition of the mixture—constrain to around 8-12, reducing real-world performance below the ideal.[25][26] In the Brayton cycle, used in gas turbines, isentropic processes occur in the compressor (1-2) and turbine (3-4), with constant-pressure heat addition and rejection completing the loop. The compressor raises the gas pressure adiabatically and reversibly, while the turbine extracts work through isentropic expansion of the hot gases. The cycle's thermal efficiency depends on the pressure ratio and is expressed as , demonstrating that increasing improves efficiency up to a point limited by material constraints and component irreversibilities.[27] The Rankine cycle, the basis for steam power plants, approximates isentropic behavior in the pump (1-2) and turbine (3-4), where the working fluid (water/steam) undergoes reversible adiabatic compression as a liquid and expansion as a vapor. Deviations from ideality, such as friction and heat losses, are analyzed using temperature-entropy (T-s) diagrams, which reveal entropy increases during real processes and quantify efficiency losses. The pump work is minimal due to the low specific volume of the liquid, while turbine expansion often results in wet steam, requiring careful design to avoid erosion.[28] Isentropic processes form the adiabatic components of the reversible Carnot cycle, the benchmark for maximum efficiency between two thermal reservoirs, consisting of two isothermal and two isentropic steps that bound the performance of practical cycles like Otto, Brayton, and Rankine. All real cycles aspire to this reversible limit, where isentropics ensure no entropy production during work transfer. In real engines, deviations from isentropic ideals—such as polytropic effects in compressors and turbines—further limit performance, emphasizing the need for high-efficiency components to close the gap.[29]Isentropic Flow in Fluids

Principles of Compressible Flow

In the context of fluid dynamics, an isentropic process models the flow of compressible fluids under inviscid and adiabatic conditions, where entropy remains constant along streamlines. This idealization applies to steady, one-dimensional flows without shocks, friction, or heat transfer, enabling reversible expansions and compressions.[30][6] The governing equations for such flows derive from conservation principles. The continuity equation ensures mass conservation: , where is density, is cross-sectional area, and is velocity. Momentum balance follows Euler's equation for inviscid flow: , with as pressure. The energy equation conserves total enthalpy: , where is specific enthalpy, representing constant stagnation enthalpy along streamlines.[30][31] The Mach number, defined as with as the local speed of sound, governs flow behavior relative to compressibility effects. For subsonic flow (), acceleration occurs in converging ducts, while deceleration happens in diverging sections. In supersonic flow (), the opposite applies: acceleration in diverging ducts and deceleration in converging ones. This dichotomy arises from the interplay of inertial and pressure forces in compressible regimes.[30][6] A key insight from these principles is the area-velocity relation, previewing how duct geometry influences speed: , indicating that area changes drive velocity adjustments differently based on Mach regime (detailed derivations follow in subsequent relations).[30] Applications of isentropic flow principles appear in nozzles for thrust generation, diffusers for flow deceleration, and wind tunnels for aerodynamic testing, typically assuming a calorically perfect gas where specific heats are constant.[6][30] The analysis relies on a quasi-one-dimensional assumption, where flow properties vary primarily along the streamwise direction and are averaged over the cross-section, simplifying multidimensional effects for duct-like geometries. Limitations include neglect of boundary layers, which introduce viscous shear and thermal gradients near walls, rendering the model inexact for real fluids with nonzero viscosity or heat conduction.[31]Isentropic Flow Relations

In isentropic compressible flow, stagnation properties describe the thermodynamic state achieved when the fluid is decelerated to rest without entropy change, serving as reference conditions for analyzing flow variations. These properties are particularly useful in duct flows, nozzles, and diffusers where kinetic energy converts to thermal energy. The relationships between static and stagnation quantities for a perfect gas are derived from the energy equation and isentropic process assumptions, yielding: where , , and are stagnation temperature, pressure, and density; , , and are static values; is the specific heat ratio; and is the Mach number.[18] These equations highlight how stagnation pressure and density increase nonlinearly with Mach number, reflecting compressible effects absent in incompressible flows.[6] The mass flow rate in steady, one-dimensional isentropic flow through a cross-sectional area is expressed in terms of local static properties as: where is the gas constant. This relation, derived from continuity, energy, and isentropic state equations, allows computation of flow capacity based on local conditions and is invariant along the duct for steady flow.[32] For choked conditions at the sonic point (), it simplifies to a maximum value dependent only on stagnation properties and throat area : Choked flow occurs in nozzles when the back pressure drops below the critical ratio for air (), fixing the throat Mach number at unity and rendering mass flow independent of further pressure reductions.[33] The area-velocity relation governs how cross-sectional area changes affect velocity in isentropic duct flow, essential for nozzle and diffuser design. Starting from the steady one-dimensional continuity equation, , differentiation yields . Combining with the isentropic momentum equation (Euler form), , and using the isentropic speed of sound definition , the density change is related to velocity as . Substituting back into the continuity differential gives the area-velocity relation: This equation indicates that for subsonic flow (), area decreases accelerate the flow (like a converging nozzle), while for supersonic flow (), area increases accelerate it (diverging section). At , the relation is singular, marking the throat where flow chokes. The derivation assumes reversible, adiabatic conditions without friction or heat transfer.[34] Key isentropic flow relations for air () are summarized in the following table, showing ratios of static to stagnation properties and area relative to the sonic throat area as functions of Mach number. These values facilitate rapid assessment of flow states without iterative calculations.[35]| M | P/P₀ | T/T₀ | A/A* | ρ/ρ₀ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ∞ | 1.0000 |

| 0.20 | 0.9725 | 0.9921 | 2.9635 | 0.9804 |

| 0.40 | 0.8956 | 0.9690 | 1.5901 | 0.9242 |

| 0.60 | 0.7840 | 0.9328 | 1.1882 | 0.8405 |

| 0.80 | 0.6560 | 0.8865 | 1.0382 | 0.7400 |

| 1.00 | 0.5283 | 0.8333 | 1.0000 | 0.6339 |

| 1.20 | 0.4124 | 0.7764 | 1.0304 | 0.5313 |

| 1.40 | 0.3142 | 0.7184 | 1.1149 | 0.4375 |

| 1.60 | 0.2353 | 0.6614 | 1.2502 | 0.3558 |

| 1.80 | 0.1740 | 0.6068 | 1.4390 | 0.2869 |

| 2.00 | 0.1278 | 0.5556 | 1.6875 | 0.2300 |

| 2.20 | 0.0923 | 0.5081 | 2.0409 | 0.1816 |

| 2.40 | 0.0640 | 0.4647 | 2.4936 | 0.1378 |

| 2.60 | 0.0435 | 0.4252 | 3.0359 | 0.1024 |

| 2.80 | 0.0290 | 0.3894 | 3.8498 | 0.0745 |

| 3.00 | 0.0272 | 0.3571 | 4.2346 | 0.0762 |

References

- https://www.grc.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/www/k-12/airplane/pvtsplot.html