Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thermodynamic process

View on Wikipedia| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

Classical thermodynamics considers three main kinds of thermodynamic processes: (1) changes in a system, (2) cycles in a system, and (3) flow processes.

(1) A Thermodynamic process is a process in which the thermodynamic state of a system is changed. A change in a system is defined by a passage from an initial to a final state of thermodynamic equilibrium. In classical thermodynamics, the actual course of the process is not the primary concern, and often is ignored. A state of thermodynamic equilibrium endures unchangingly unless it is interrupted by a thermodynamic operation that initiates a thermodynamic process. The equilibrium states are each respectively fully specified by a suitable set of thermodynamic state variables, that depend only on the current state of the system, not on the path taken by the processes that produce the state. In general, during the actual course of a thermodynamic process, the system may pass through physical states which are not describable as thermodynamic states, because they are far from internal thermodynamic equilibrium. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics, however, considers processes in which the states of the system are close to thermodynamic equilibrium, and aims to describe the continuous passage along the path, at definite rates of progress.

As a useful theoretical but not actually physically realizable limiting case, a process may be imagined to take place practically infinitely slowly or smoothly enough to allow it to be described by a continuous path of equilibrium thermodynamic states, when it is called a "quasi-static" process. This is a theoretical exercise in differential geometry, as opposed to a description of an actually possible physical process; in this idealized case, the calculation may be exact.

A really possible or actual thermodynamic process, considered closely, involves friction. This contrasts with theoretically idealized, imagined, or limiting, but not actually possible, quasi-static processes which may occur with a theoretical slowness that avoids friction. It also contrasts with idealized frictionless processes in the surroundings, which may be thought of as including 'purely mechanical systems'; this difference comes close to defining a thermodynamic process.[1]

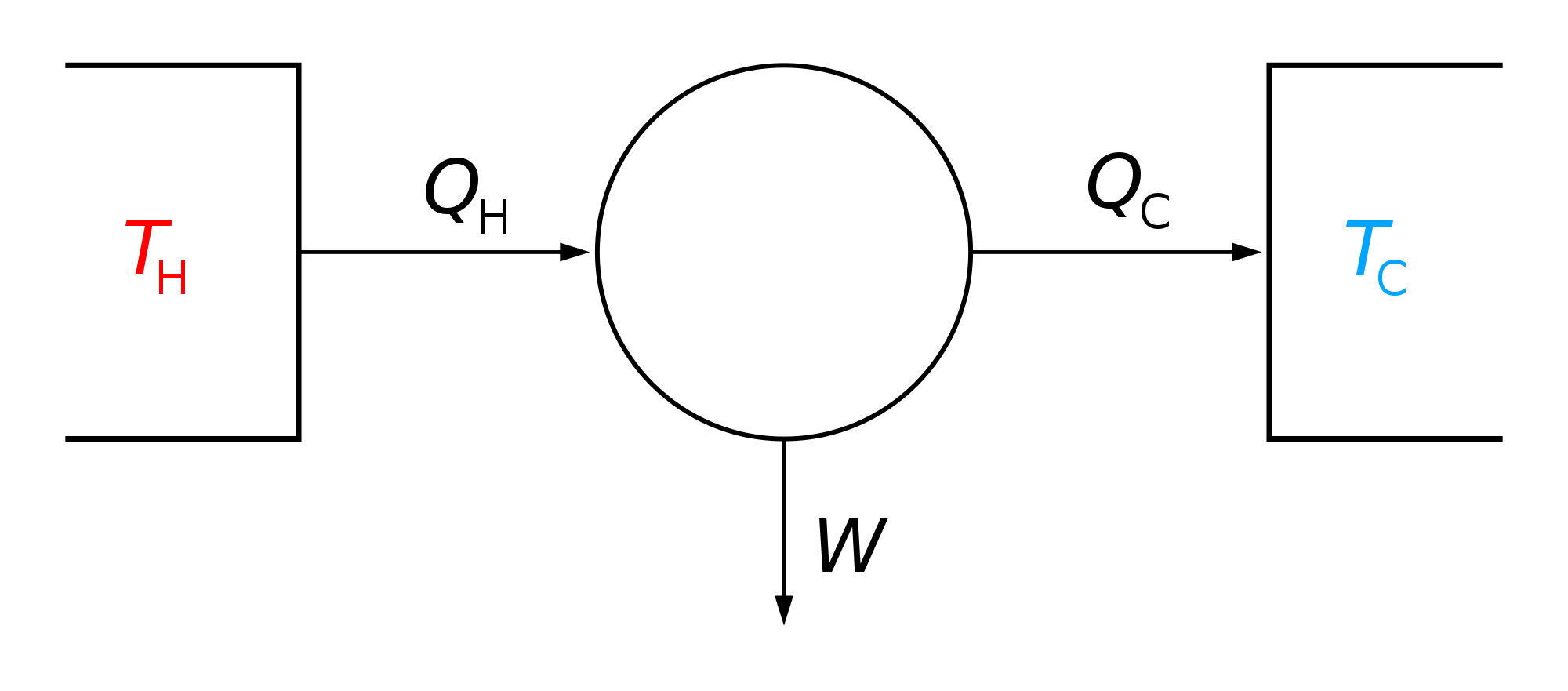

(2) A cyclic process carries the system through a cycle of stages, starting and being completed in some particular state. The descriptions of the staged states of the system are not the primary concern. The primary concern is the sums of matter and energy inputs and outputs to the cycle. Cyclic processes were important conceptual devices in the early days of thermodynamical investigation, while the concept of the thermodynamic state variable was being developed.

(3) Defined by flows through a system, a flow process is a steady state of flows into and out of a vessel with definite wall properties. The internal state of the vessel contents is not the primary concern. The quantities of primary concern describe the states of the inflow and the outflow materials, and, on the side, the transfers of heat, work, and kinetic and potential energies for the vessel. Flow processes are of interest in engineering.

Kinds of process

[edit]Cyclic process

[edit]Defined by a cycle of transfers into and out of a system, a cyclic process is described by the quantities transferred in the several stages of the cycle. The descriptions of the staged states of the system may be of little or even no interest. A cycle is a sequence of a small number of thermodynamic processes that indefinitely often, repeatedly returns the system to its original state. For this, the staged states themselves are not necessarily described, because it is the transfers that are of interest. It is reasoned that if the cycle can be repeated indefinitely often, then it can be assumed that the states are recurrently unchanged. The condition of the system during the several staged processes may be of even less interest than is the precise nature of the recurrent states. If, however, the several staged processes are idealized and quasi-static, then the cycle is described by a path through a continuous progression of equilibrium states.

Flow process

[edit]Defined by flows through a system, a flow process is a steady state of flow into and out of a vessel with definite wall properties. The internal state of the vessel contents is not the primary concern. The quantities of primary concern describe the states of the inflow and the outflow materials, and, on the side, the transfers of heat, work, and kinetic and potential energies for the vessel. The states of the inflow and outflow materials consist of their internal states, and of their kinetic and potential energies as whole bodies. Very often, the quantities that describe the internal states of the input and output materials are estimated on the assumption that they are bodies in their own states of internal thermodynamic equilibrium. Because rapid reactions are permitted, the thermodynamic treatment may be approximate, not exact.

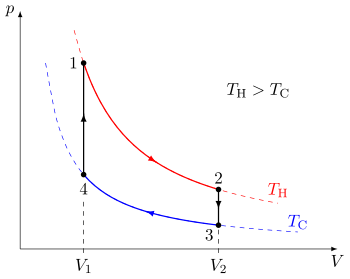

A cycle of quasi-static processes

[edit]

A quasi-static thermodynamic process can be visualized by graphically plotting the path of idealized changes to the system's state variables. In the example, a cycle consisting of four quasi-static processes is shown. Each process has a well-defined start and end point in the pressure-volume state space. In this particular example, processes 1 and 3 are isothermal, whereas processes 2 and 4 are isochoric. The PV diagram is a particularly useful visualization of a quasi-static process, because the area under the curve of a process is the amount of work done by the system during that process. Thus work is considered to be a process variable, as its exact value depends on the particular path taken between the start and end points of the process. Similarly, heat may be transferred during a process, and it too is a process variable.

Conjugate variable processes

[edit]It is often useful to group processes into pairs, in which each variable held constant is one member of a conjugate pair.

Pressure – volume

[edit]The pressure–volume conjugate pair is concerned with the transfer of mechanical energy as the result of work.

- An isobaric process occurs at constant pressure. An example would be to have a movable piston in a cylinder, so that the pressure inside the cylinder is always at atmospheric pressure, although it is separated from the atmosphere. In other words, the system is dynamically connected, by a movable boundary, to a constant-pressure reservoir.

- An isochoric process is one in which the volume is held constant, with the result that the mechanical PV work done by the system will be zero. On the other hand, work can be done isochorically on the system, for example by a shaft that drives a rotary paddle located inside the system. It follows that, for the simple system of one deformation variable, any heat energy transferred to the system externally will be absorbed as internal energy. An isochoric process is also known as an isometric process or an isovolumetric process. An example would be to place a closed tin can of material into a fire. To a first approximation, the can will not expand, and the only change will be that the contents gain internal energy, evidenced by increase in temperature and pressure. Mathematically, . The system is dynamically insulated, by a rigid boundary, from the environment.

Temperature – entropy

[edit]The temperature-entropy conjugate pair is concerned with the transfer of energy, especially for a closed system.

- An isothermal process occurs at a constant temperature. An example would be a closed system immersed in and thermally connected with a large constant-temperature bath. Energy gained by the system, through work done on it, is lost to the bath, so that its temperature remains constant.

- An adiabatic process is a process in which there is no matter or heat transfer, because a thermally insulating wall separates the system from its surroundings. For the process to be natural, either (a) work must be done on the system at a finite rate, so that the internal energy of the system increases; the entropy of the system increases even though it is thermally insulated; or (b) the system must do work on the surroundings, which then suffer increase of entropy, as well as gaining energy from the system.

- An isentropic process is customarily defined as an idealized quasi-static reversible adiabatic process, of transfer of energy as work. Otherwise, for a constant-entropy process, if work is done irreversibly, heat transfer is necessary, so that the process is not adiabatic, and an accurate artificial control mechanism is necessary; such is therefore not an ordinary natural thermodynamic process.

Chemical potential - particle number

[edit]The processes just above have assumed that the boundaries are also impermeable to particles. Otherwise, we may assume boundaries that are rigid, but are permeable to one or more types of particle. Similar considerations then hold for the chemical potential–particle number conjugate pair, which is concerned with the transfer of energy via this transfer of particles.

- In a constant chemical potential process the system is particle-transfer connected, by a particle-permeable boundary, to a constant-μ reservoir.

- The conjugate here is a constant particle number process. These are the processes outlined just above. There is no energy added or subtracted from the system by particle transfer. The system is particle-transfer-insulated from its environment by a boundary that is impermeable to particles, but permissive of transfers of energy as work or heat. These processes are the ones by which thermodynamic work and heat are defined, and for them, the system is said to be closed.

Thermodynamic potentials

[edit]Any of the thermodynamic potentials may be held constant during a process. For example:

- An isenthalpic process introduces no change in enthalpy in the system.

Polytropic processes

[edit]A polytropic process is a thermodynamic process that obeys the relation:

where P is the pressure, V is volume, n is any real number (the "polytropic index"), and C is a constant. This equation can be used to accurately characterize processes of certain systems, notably the compression or expansion of a gas, but in some cases, liquids and solids.

Processes classified by the second law of thermodynamics

[edit]According to Planck, one may think of three main classes of thermodynamic process: natural, fictively reversible, and impossible or unnatural.[2][3]

Natural process

[edit]Only natural processes occur in nature. For thermodynamics, a natural process is a transfer between systems that increases the sum of their entropies, and is irreversible.[2] Natural processes may occur spontaneously upon the removal of a constraint, or upon some other thermodynamic operation, or may be triggered in a metastable or unstable system, as for example in the condensation of a supersaturated vapour.[4] Planck emphasised the occurrence of friction as an important characteristic of natural thermodynamic processes that involve transfer of matter or energy between system and surroundings.

Effectively reversible process

[edit]To describe the geometry of graphical surfaces that illustrate equilibrium relations between thermodynamic functions of state, no one can fictively think of so-called "reversible processes". They are convenient theoretical objects that trace paths across graphical surfaces. They are called "processes" but do not describe naturally occurring processes, which are always irreversible. Because the points on the paths are points of thermodynamic equilibrium, it is customary to think of the "processes" described by the paths as fictively "reversible".[2] Reversible processes are always quasistatic processes, but the converse is not always true.

Unnatural process

[edit]Unnatural processes are logically conceivable but do not occur in nature. They would decrease the sum of the entropies if they occurred.[2]

Quasistatic process

[edit]A quasistatic process is an idealized or fictive model of a thermodynamic "process" considered in theoretical studies. It does not occur in physical reality. It may be imagined as happening infinitely slowly so that the system passes through a continuum of states that are infinitesimally close to equilibrium.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reiss, H. (1965). Methods of Thermodynamics, Blaisdell, New York, page 52: "The frictionless systems may be referred to as purely mechanical systems whereas those with friction are thermodynamic systems."

- ^ a b c d Guggenheim, E.A. (1949/1967). Thermodynamics. An Advanced Treatment for Chemists and Physicists, fifth revised edition, North-Holland, Amsterdam, p. 12.

- ^ Tisza, L. (1966). Generalized Thermodynamics, M.I.T. Press, Cambridge MA, p. 32.

- ^ Planck, M.(1897/1903). Treatise on Thermodynamics, translated by A. Ogg, Longmans, Green & Co., London, p. 82.

Further reading

[edit]- Physics for Scientists and Engineers - with Modern Physics (6th Edition), P. A. Tipler, G. Mosca, Freeman, 2008, ISBN 0-7167-8964-7

- Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN 3-527-26954-1 (Verlagsgesellschaft), ISBN 0-89573-752-3 (VHC Inc.)

- McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C.B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3

- Physics with Modern Applications, L.H. Greenberg, Holt-Saunders International W.B. Saunders and Co, 1978, ISBN 0-7216-4247-0

- Essential Principles of Physics, P.M. Whelan, M.J. Hodgeson, 2nd Edition, 1978, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-3382-1

- Thermodynamics, From Concepts to Applications (2nd Edition), A. Shavit, C. Gutfinger, CRC Press (Taylor and Francis Group, USA), 2009, ISBN 9781420073683

- Chemical Thermodynamics, D.J.G. Ives, University Chemistry, Macdonald Technical and Scientific, 1971, ISBN 0-356-03736-3

- Elements of Statistical Thermodynamics (2nd Edition), L.K. Nash, Principles of Chemistry, Addison-Wesley, 1974, ISBN 0-201-05229-6

- Statistical Physics (2nd Edition), F. Mandl, Manchester Physics, John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 9780471915331

Thermodynamic process

View on Grokipedia- Isothermal processes, where temperature remains constant (ΔT = 0), often requiring heat exchange with a reservoir to maintain equilibrium, as in slow expansions of ideal gases following pV = constant.[1]

- Adiabatic processes, characterized by no heat transfer (Q = 0), where work done changes internal energy and thus temperature, leading to cooling during expansion or heating during compression.[2]

- Isobaric processes, with constant pressure (P = constant), allowing volume and temperature to vary proportionally via the ideal gas law.[3]

- Isochoric processes, where volume is fixed (V = constant), so changes in pressure or temperature occur without work, solely through heat addition or removal.[2]

- Additional specialized types, such as isentropic (constant entropy, reversible and adiabatic), isenthalpic (constant enthalpy, as in throttling), and polytropic (following PV^k = constant for some k), which generalize behaviors in engineering applications like turbines and compressors.[3]