Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

JTAG (named after the Joint Test Action Group which codified it) is an industry standard for verifying designs of and testing printed circuit boards after manufacture.

JTAG implements standards for on-chip instrumentation in electronic design automation (EDA) as a complementary tool to digital simulation.[1] It specifies the use of a dedicated debug port implementing a serial communications interface for low-overhead access without requiring direct external access to the system address and data buses. The interface connects to an on-chip Test Access Port (TAP) that implements a stateful protocol to access a set of test registers that present chip logic levels and device capabilities of various parts.

The Joint Test Action Group formed in 1985 to develop a method of verifying designs and testing printed circuit boards after manufacture. In 1990 the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers codified the results of the effort in IEEE Standard 1149.1-1990, entitled Standard Test Access Port and Boundary-Scan Architecture.

The JTAG standards have been extended by multiple semiconductor chip manufacturers with specialized variants to provide vendor-specific features.[2]

History

[edit]In the 1980s, multi-layer circuit boards and integrated circuits (ICs) using ball grid array and similar mounting technologies were becoming standard, and connections were being made between ICs that were not available to probes. The majority of manufacturing and field faults in circuit boards were due to poor solder joints on the boards, imperfections among board connections, or the bonds and bond wires from IC pads to pin lead frames. The Joint Test Action Group (JTAG) was formed in 1985 to provide a pins-out view from one IC pad to another so these faults could be discovered.

The industry standard became an IEEE standard in 1990 as IEEE Std. 1149.1-1990[3] after years of initial use. In the same year, Intel released their first processor with JTAG (the 80486) which led to quicker industry adoption by all manufacturers. In 1994, a supplement that contains a description of the boundary scan description language (BSDL) was added. Further refinements regarding the use of all-zeros for EXTEST, separating the use of SAMPLE from PRELOAD and better implementation for OBSERVE_ONLY cells were made and released in 2001.[4] Since 1990, this standard has been adopted by electronics companies around the world. Boundary scan is now mostly synonymous with JTAG, but JTAG has essential uses beyond such manufacturing applications. The 2013[5] revision of IEEE Std. 1149.1 has introduced a vast set of optional features, associated extensions to BSDL, and a new procedural description language (PDL) based on Tcl.

Debugging

[edit]Although JTAG's early applications targeted board-level testing, here the JTAG standard was designed to assist with device, board, and system testing, diagnosis, and fault isolation. Today JTAG is used as the primary means of accessing sub-blocks of integrated circuits, making it an essential mechanism for debugging embedded systems which might not have any other debug-capable communications channel.[citation needed] On most systems, JTAG-based debugging is available from the very first instruction after CPU reset, letting it assist with development of early boot software which runs before anything is set up. An in-circuit emulator (or, more correctly, a JTAG adapter) uses JTAG as the transport mechanism to access on-chip debug modules inside the target CPU. Those modules let software developers debug the software of an embedded system directly at the machine instruction level when needed, or (more typically) in terms of high-level language source code.

System software debug support is for many software developers the main reason to be interested in JTAG. Multiple silicon architectures such as PowerPC, MIPS, ARM, and x86 built an entire software debug, instruction tracing, and data tracing infrastructure around the basic JTAG protocol. Frequently individual silicon vendors however only implement parts of these extensions. Some examples are ARM CoreSight and Nexus as well as Intel's BTS (Branch Trace Storage), LBR (Last Branch Record), and IPT (Intel Processor Trace) implementations. There are a number of other such silicon vendor-specific extensions that may not be documented except under NDA. The adoption of the JTAG standard helped move JTAG-centric debugging environments away from early processor-specific designs. Processors can normally be halted, single stepped, or let run freely. One can set code breakpoints, both for code in RAM (often using a special machine instruction e.g. INT3) and in ROM/flash. Data breakpoints are often available, as is bulk data download to RAM. Most designs have halt mode debugging, but some allow debuggers to access registers and data buses without needing to halt the core being debugged. Some toolchains can use ARM Embedded Trace Macrocell (ETM) modules, or equivalent implementations in other architectures to trigger debugger (or tracing) activity on complex hardware events, like a logic analyzer programmed to ignore the first seven accesses to a register from one particular subroutine.

Sometimes FPGA developers also use JTAG to develop debugging tools.[6] The same JTAG techniques used to debug software running inside a CPU can help debug other digital design blocks inside an FPGA. For example, custom JTAG instructions can be provided to allow reading registers built from arbitrary sets of signals inside the FPGA, providing visibility for behaviors that are invisible to boundary scan operations. Similarly, writing such registers could provide controllability that is not otherwise available.

Storing firmware

[edit]JTAG allows device programmer hardware to transfer data into internal non-volatile device memory (e.g., CPLDs). Some device programmers serve a double purpose for programming as well as debugging the device. In the case of FPGAs, volatile memory devices can also be programmed via the JTAG port, normally during development work. In addition, internal monitoring capabilities (temperature, voltage, and current) may be accessible via the JTAG port.

JTAG programmers are also used to write software and data into flash memory. This is usually done using the same data bus access the CPU would use, and is sometimes handled by the CPU. In other cases the memory chips themselves have JTAG interfaces. Some modern debug architectures provide internal and external bus master access without needing to halt and take over a CPU. In the worst case, it is usually possible to drive external bus signals using the boundary scan facility.

As a practical matter, when developing an embedded system, emulating the instruction store is the fastest way to implement the debug cycle (edit, compile, download, test, and debug).[citation needed] This is because the in-circuit emulator simulating an instruction store can be updated very quickly from the development host via, say, USB. Using a serial UART port and bootloader to upload firmware to Flash makes this debug cycle quite slow and possibly expensive in terms of tools; installing firmware into Flash (or SRAM instead of Flash) via JTAG is an intermediate solution between these extremes.

Boundary scan testing

[edit]JTAG boundary scan technology provides access to a number of logic signals of a complex integrated circuit, including the device pins. The signals are represented in the boundary scan register (BSR) accessible via the TAP. This permits testing as well as controlling the states of the signals for testing and debugging. Therefore, both software and hardware (manufacturing) faults may be located and an operating device may be monitored.

When combined with built-in self-test (BIST), the JTAG scan chain enables a low overhead, embedded solution to test an IC for certain static faults (shorts, opens, and logic errors). The scan chain mechanism does not generally help diagnose or test for timing, temperature or other dynamic operational errors that may occur. Test cases are often provided in standardized formats such as SVF, or its binary sibling XSVF, and used in production tests. The ability to perform such testing on finished boards is an essential part of Design For Test in today's products, increasing the number of faults that can be found before products ship to customers.

Electrical characteristics

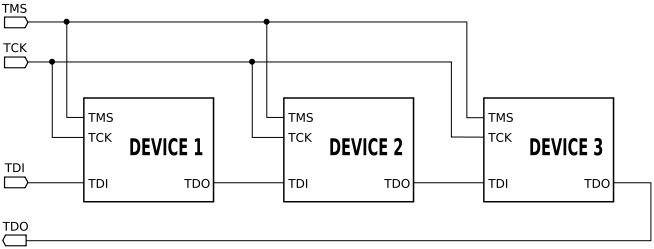

[edit]A JTAG interface is a special interface added to a chip. Depending on the version of JTAG, two, four, or five pins are added. The four and five pin interfaces are designed so that multiple chips on a board can have their JTAG lines daisy-chained together if specific conditions are met.[7] The two-pin interface is designed so that multiple chips can be connected in a star topology. In either case, a test probe need only connect to a single JTAG port to have access to all chips on a circuit board.

Daisy-chained JTAG (IEEE 1149.1)

[edit]

The connector pins are:

- TDI (Test Data In)

- TDO (Test Data Out)

- TCK (Test Clock)

- TMS (Test Mode Select)

- TRST (Test Reset) optional.

The TRST pin is an optional active-low reset to the test logic, usually asynchronous, but sometimes synchronous, depending on the chip. If the pin is not available, the test logic can be reset by switching to the reset state synchronously, using TCK and TMS. Note that resetting test logic doesn't necessarily imply resetting anything else. There are generally some processor-specific JTAG operations which can reset all or part of the chip being debugged.

Since only one data line is available, the protocol is serial. The clock input is at the TCK pin. One bit of data is transferred in from TDI, and out to TDO per TCK rising clock edge. Different instructions can be loaded. Instructions for typical ICs might read the chip ID, sample input pins, drive (or float) output pins, manipulate chip functions, or bypass (pipe TDI to TDO to logically shorten chains of multiple chips).

As with any clocked signal, data presented to TDI must be valid for some chip-specific Setup time before and Hold time after the relevant (here, rising) clock edge. TDO data is valid for some chip-specific time after the falling edge of TCK.

The maximum operating frequency of TCK varies depending on all chips in the chain (the lowest speed must be used), but it is typically 10-100 MHz (100-10 ns per bit). Also TCK frequencies depend on board layout and JTAG adapter capabilities and state. One chip might have a 40 MHz JTAG clock, but only if it is using a 200 MHz clock for non-JTAG operations; and it might need to use a much slower clock when it is in a low-power mode. Accordingly, some JTAG adapters have adaptive clocking using an RTCK (Return TCK) signal. Faster TCK frequencies are most useful when JTAG is used to transfer much data, such as when storing a program executable into flash memory.

Clocking changes on TMS steps through a standardized JTAG state machine. The JTAG state machine can reset, access an instruction register, or access data selected by the instruction register.

JTAG platforms often add signals to the handful defined by the IEEE 1149.1 specification. A System Reset (SRST) signal is quite common, letting debuggers reset the whole system, not just the parts with JTAG support. Sometimes there are event signals used to trigger activity by the host or by the device being monitored through JTAG; or, perhaps, additional control lines.

Even though few consumer products provide an explicit JTAG port connector, the connections are often available on the printed circuit board as a remnant from development prototyping and/or production. When exploited, these connections often provide the most viable means for reverse engineering.

Reduced pin count JTAG (IEEE 1149.7)

[edit]

Reduced pin count JTAG uses only two wires, a clock wire and a data wire. This is defined as part of the IEEE 1149.7 standard.[8] The connector pins are:

- TMSC (Test Serial Data)

- TCK (Test Clock)

It is called cJTAG for compact JTAG.

The two-wire interface reduced pressure on the number of pins, and devices can be connected in a star topology.[9] The star topology enables some parts of the system to be powered down, while others can still be accessed over JTAG; a daisy chain requires all JTAG interfaces to be powered. Other two-wire interfaces exist, such as Serial Wire Debug (SWD) and Spy-Bi-Wire (SBW).

Communications model

[edit]In JTAG, devices expose one or more test access ports (TAPs). The picture above shows three TAPs, which might be individual chips or might be modules inside one chip. A daisy chain of TAPs is called a scan chain, or (loosely) a target. Scan chains can be arbitrarily long, but in practice, twenty TAPs is unusually long.[citation needed]

To use JTAG, a host is connected to the target's JTAG signals (TMS, TCK, TDI, TDO, etc.) through some kind of JTAG adapter, which may need to handle issues like level shifting and galvanic isolation. The adapter connects to the host using some interface such as USB, PCI, Ethernet, and so forth.

Primitives

[edit]The host communicates with the TAPs by manipulating TMS and TDI in conjunction with TCK and reading results through TDO (which is the only standard host-side input). TMS/TDI/TCK output transitions create the basic JTAG communication primitive on which higher layer protocols build:

- State switching ... All TAPs are in the same state, and that state changes on TCK transitions. This JTAG state machine is part of the JTAG spec and includes sixteen states. There are six stable states where keeping TMS stable prevents the state from changing. In all other states, TCK always changes that state. In addition, asserting TRST forces entry to one of those stable states (Test_Logic_Reset), in a slightly quicker way than the alternative of holding TMS high and cycling TCK five times.

- Shifting ... Most parts of the JTAG state machine support two stable states used to transfer data. Each TAP has an instruction register (IR) and a data register (DR). The size of those registers varies between TAPs, and those registers are combined through TDI and TDO to form a large shift register. (The size of the DR is a function of the value in that TAP's current IR, and possibly of the value specified by a SCAN_N instruction.) There are three operations defined on that shift register:

- Capturing a temporary value

- Entry to the Shift_IR stable state goes via the Capture_IR state, loading the shift register with a partially fixed value (not the current instruction)

- Entry to the Shift_DR stable state goes via the Capture_DR state, loading the value of the Data Register specified by the TAP's current IR.

- Shifting that value bit-by-bit, in either the Shift_IR or Shift_DR stable state; TCK transitions shift the shift register one bit, from TDI towards TDO, exactly like a SPI mode 1 data transfer through a daisy chain of devices (with TMS=0 acting like the chip select signal, TDI as MOSI, etc.).

- Updating IR or DR from the temporary value shifted in, on transition through the Update_IR or Update_DR state. Note that it is not possible to read (capture) a register without writing (updating) it, and vice versa. A common idiom adds flag bits to say whether the update should have side effects, or whether the hardware is ready to execute such side effects.

- Capturing a temporary value

- Running ... One stable state is called Run_Test/Idle. The distinction is TAP-specific. Clocking TCK in the Idle state has no particular side effects, but clocking it in the Run_Test state may change system state. For example, some ARM9 cores support a debugging mode where TCK cycles in the Run_Test state drive the instruction pipeline.

At a basic level, using JTAG involves reading and writing instructions and their associated data registers; and sometimes involves running a number of test cycles. Behind those registers is hardware that is not specified by JTAG, and which has its own states that is affected by JTAG activities.

Most JTAG hosts use the shortest path between two states, perhaps constrained by quirks of the adapter. (For example, one adapter[which?] only handles paths whose lengths are multiples of seven bits.) Some layers built on top of JTAG monitor the state transitions and use uncommon paths to trigger higher-level operations. Some ARM cores use such sequences to enter and exit a two-wire (non-JTAG) SWD mode. A Zero Bit Scan (ZBS) sequence is used in IEEE 1149.7[8] to access advanced functionality such as switching TAPs into and out of scan chains, power management, and a different two-wire mode.

JTAG IEEE Std 1149.1 (boundary scan) instructions

[edit]Instruction register sizes tend to be small, perhaps four or seven bits wide. Except for BYPASS and EXTEST, all instruction opcodes are defined by the TAP implementer, as are their associated data registers; undefined instruction codes should not be used. Two key instructions are:

- The BYPASS instruction, an opcode of all ones regardless of the TAP's instruction register size, must be supported by all TAPs. The instruction selects a single-bit data register (also called BYPASS). The instruction allows this device to be bypassed (do nothing) while other devices in the scan path are exercised.[4]

- The optional IDCODE instruction, with an implementer-defined opcode. IDCODE is associated with a 32-bit register (IDCODE). Its data uses a standardized format that includes a manufacturer code (derived from the JEDEC Standard Manufacturer's Identification Code standard, JEP-106), a part number assigned by the manufacturer, and a part version code. IDCODE is widely, but not universally, supported.

On exit from the RESET state, the instruction register is preloaded with either BYPASS or IDCODE. This allows JTAG hosts to identify the size and, at least partially, contents of the scan chain to which they are connected. (They can enter the RESET state then scan the Data Register until they read back the data they wrote. A BYPASS register has only a zero bit; while an IDCODE register is 32 bits and starts with a one. So the bits not written by the host can easily be mapped to TAPs.) Such identification is often used to sanity-check manual configuration since IDCODE is often unspecific. It could for example identify an ARM Cortex-M3-based microcontroller, without specifying the microcontroller vendor or model; or a particular FPGA, but not how it has been programmed.

A common idiom involves shifting BYPASS into the instruction registers of all TAPs except one, which receives some other instruction. That way all TAPs except one expose a single-bit data register, and values can be selectively shifted into or out of that one TAP's data register without affecting any other TAP.

The IEEE 1149.1 (JTAG) standard describes a number of instructions to support boundary scan applications. Some of these instructions are mandatory, but TAPs used for debug instead of boundary scan testing sometimes provide minimal or no support for these instructions. Those mandatory instructions operate on the Boundary Scan Register (BSR) defined in the BSDL file, and include:

- EXTEST for external testing, such as using pins to probe board-level behaviors

- PRELOAD loading pin output values before EXTEST (sometimes combined with SAMPLE)

- SAMPLE reading pin values into the boundary scan register

IEEE-defined optional instructions include:

- CLAMP a variant of BYPASS that drives the output pins using the PRELOADed values

- HIGHZ deactivates the outputs of all pins

- INTEST for internal testing, such as using pins to probe on-chip behaviors

- RUNBIST places the chip in a self-test mode

- USERCODE returns a user-defined code, for example, to identify which FPGA image is active

Devices may define more instructions, and those definitions should be part of a BSDL file provided by the manufacturer. They are often only marked as PRIVATE.

Boundary scan register

[edit]Devices communicate to the world via a set of input and output pins. By themselves, these pins provide limited visibility into the workings of the device. However, devices that support boundary scan contain a shift-register cell for each signal pin of the device. These registers are connected in a dedicated path around the device's boundary (hence the name). The path creates a virtual access capability that circumvents the normal inputs and outputs, providing direct control of the device and detailed visibility for signals.[10]

The contents of the boundary scan register, including signal I/O capabilities, are usually described by the manufacturer using a part-specific BSDL file. These are used with design 'netlists' from CAD/EDA systems to develop tests used in board manufacturing. Commercial test systems often cost several thousand dollars for a complete system and include diagnostic options to pinpoint faults such as open circuits and shorts. They may also offer schematic or layout viewers to depict the fault in a graphical manner.

To enable boundary scanning, IC vendors add logic to each of their devices, including scan cells for each of the signal pins. These cells are then connected together to form the boundary scan shift register (BSR), which is connected to a TAP controller. These designs are parts of most Verilog or VHDL libraries. Overhead for this additional logic is minimal, and generally is well worth the price to enable efficient testing at the board level.

Example: ARM11 debug TAP

[edit]An example helps show the operation of JTAG in real systems. The example here is the debug TAP of an ARM11 processor, the ARM1136[11] core. The processor itself has extensive JTAG capability, similar to what is found in other CPU cores, and it is integrated into chips with even more extensive capabilities accessed through JTAG.

This is a non-trivial example, which is representative of a significant cross section of JTAG-enabled systems. In addition, it shows how control mechanisms are built using JTAG's register read/write primitives, and how those combine to facilitate testing and debugging complex logic elements; CPUs are common, but FPGAs and ASICs include other complex elements which need to be debugged.

Licensees of this core integrate it into chips, usually combining it with other TAPs as well as numerous peripherals and memory. One of those other TAPs handles boundary scan testing for the whole chip; it is not supported by the debug TAP. Examples of such chips include:

- The OMAP2420, which includes a boundary scan TAP, the ARM1136 Debug TAP, an ETB11 trace buffer TAP, a C55x DSP, and a TAP for an ARM7 TDMI-based imaging engine, with the boundary scan TAP ("ICEpick-B") having the ability to splice TAPs into and out of the JTAG scan chain.[12]

- The i.MX31 processor, which is similar, although its "System JTAG" boundary scan TAP,[13] which is very different from ICEpick, and it includes a TAP for its DMA engine instead of a DSP and imaging engine.

Those processors are both intended for use in wireless handsets such as cell phones, which is part of the reason they include TAP controllers which modify the JTAG scan chain: Debugging low power operation requires accessing chips when they are largely powered off, and thus when not all TAPs are operational. That scan chain modification is one subject of a forthcoming IEEE 1149.7[8] standard.

JTAG facilities

[edit]This debug TAP exposes several standard instructions, and a few specifically designed for hardware-assisted debugging, where a software tool (the debugger) uses JTAG to communicate with a system being debugged:

BYPASSandIDCODE, standard instructions as described aboveEXTEST,INTEST, standard instructions, but operating on the core instead of an external boundary scan chain.EXTESTis nominally for writing data to the core,INTESTis nominally for reading it; but two scan chains are exceptions to that rule.SCAN_NARM instruction to select the numbered scan chain used withEXTESTorINTEST. There are six scan chains:0- Device ID Register, 40 bits of read-only identification data1- Debug Status and Control Register (DSCR), 32 bits used to operate the debug facilities4- Instruction Transfer Register (ITR), 33 bits (32 instruction plus one status bit) used to execute processor instructions while in a special debug mode (see below)5- Debug Communications Channel (DCC), 34 bits (one long data word plus two status bits) used for bidirectional data transfer to the core. This is used both in debug mode and possibly at runtime when talking to debugger-aware software.6- Embedded Trace Module (ETM), 40 bits (7-bit address, one 32-bit long data word, and a R/W bit) used to control the operation of a passive instruction and data trace mechanism. This feeds either an on-chip Embedded Trace Buffer (ETB) or an external high-speed trace data collection pod. Tracing supports passive debugging (examining execution history) and profiling for performance tuning.7- debug module, 40 bits (7-bit address, one 32-bit long data word, and a R/W bit) used to access hardware breakpoints, watchpoints, and more. These can be written while the processor is running; it does not need to be in Debug Mode.

HALTandRESTART, ARM11-specific instructions to halt and restart the CPU. Halting it puts the core into the debug mode, where the ITR can be used to execute instructions, including using the DCC to transfer data between the debug (JTAG) host and the CPU.ITRSEL, ARM11-specific instruction to accelerate some operations with ITR.

That model resembles the model used in other ARM cores. Non-ARM systems generally have similar capabilities, perhaps implemented using the Nexus protocols on top of JTAG, or other vendor-specific schemes.

Older ARM7 and ARM9 cores include an EmbeddedICE module[14] which combines most of those facilities, but has an awkward mechanism for instruction execution: the debugger must drive the CPU instruction pipeline, clock by clock, and directly access the data buses to read and write data to the CPU. The ARM11 uses the same model for trace support (ETM, ETB) as those older cores.

Newer ARM Cortex cores closely resemble this debug model, but build on a Debug Access Port (DAP) instead of direct CPU access. In this architecture (named CoreSight Technology), core and JTAG module is completely independent. They are also decoupled from JTAG so they can be hosted over ARM's two-wire SWD interface (see below) instead of just the six-wire JTAG interface. (ARM takes the four standard JTAG signals and adds the optional TRST, plus the RTCK signal used for adaptive clocking.) The CoreSight JTAG-DP is asynchronous to the core clocks, and does not implement RTCK.[15] Also, the newer cores have updated trace support.

Halt mode debugging

[edit]One basic way to debug software is to present a single-threaded model, where the debugger periodically stops execution of the program and examines its state as exposed by register contents and memory (including peripheral controller registers). When interesting program events approach, a person may want to single step instructions (or lines of source code) to watch how a particular misbehavior happens.

So for example a JTAG host might HALT the core, entering debug mode, and then read CPU registers using ITR and DCC. After saving processor state, it could write those registers with whatever values it needs, then execute arbitrary algorithms on the CPU, accessing memory and peripherals to help characterize the system state. After the debugger performs those operations, the state may be restored and execution continued using the RESTART instruction.

Debug mode is also entered asynchronously by the debug module triggering a watchpoint or breakpoint, or by issuing a BKPT (breakpoint) instruction from the software being debugged. When it is not being used for instruction tracing, the ETM can also trigger entry to debug mode; it supports complex triggers sensitive to state and history, as well as the simple address comparisons exposed by the debug module. Asynchronous transitions to debug mode are detected by polling the DSCR register. This is how single stepping is implemented: HALT the core, set a temporary breakpoint at the next instruction or next high-level statement, RESTART, poll DSCR until you detect asynchronous entry to debug state, remove that temporary breakpoint, repeat.

Monitor mode debugging

[edit]Modern software is often too complex to work well with such a single-threaded model. For example, a processor used to control a motor (perhaps one driving a saw blade) may not be able to safely enter halt mode; it may need to continue handling interrupts to ensure physical safety of people and/or machinery. Issuing a HALT instruction using JTAG might be dangerous.

ARM processors support an alternative debug mode, called Monitor Mode, to work with such situations. (This is distinct from the Secure Monitor Mode implemented as part of security extensions on newer ARM cores; it manages debug operations, not security transitions.) In those cases, breakpoints and watchpoints trigger a special kind of hardware exception, transferring control to a debug monitor running as part of the system software. This monitor communicates with the debugger using the DCC and could arrange for example to single step only a single process while other processes (and interrupt handlers) continue running.

Common extensions

[edit]Microprocessor vendors have often defined their own core-specific debugging extensions. Such vendors include Infineon, MIPS with EJTAG, and more. If the vendor does not adopt a standard (such as the ones used by ARM processors; or Nexus), they need to define their own solution. If they support boundary scan, they generally build debugging over JTAG.

Freescale has COP and OnCE (On-Chip Emulation). OnCE includes a JTAG command which makes a TAP enter a special mode where the IR holds OnCE debugging commands[16] for operations such as single stepping, breakpointing, and accessing registers or memory. It also defines EOnCE (Enhanced On-Chip Emulation)[17] presented as addressing real-time concerns.

ARM has an extensive processor core debug architecture (CoreSight) that started with EmbeddedICE (a debug facility available on most ARM cores), and now includes a number of additional components such as an ETM (Embedded Trace Macrocell), with a high-speed trace port, supporting multi-core and multithread tracing. Note that tracing is non-invasive; systems do not need to stop operating to be traced. (However, trace data is too voluminous to use JTAG as more than a trace control channel.)

Nexus defines a processor debug infrastructure which is largely vendor-independent. One of its hardware interfaces is JTAG. It also defines a high-speed auxiliary port interface, used for tracing and more. Nexus is used with some newer platforms, such as the Atmel AVR32 and Freescale MPC5500 series processors.

Uses

[edit]- Except for some of the very lowest-end systems, essentially all embedded systems platforms have a JTAG port to support in-circuit debugging and firmware programming as well as for boundary scan testing:

- ARM architecture processors come with JTAG support, sometimes supporting a two-wire SWD variant or high-speed tracing of traffic on instruction or data buses.

- Modern 8-bit and 16-bit microcontroller chips, such as Atmel AVR and TI MSP430 chips, support JTAG programming and debugging. However, the very smallest chips may not have enough pins to spare (and thus tend to rely on proprietary single-wire programming interfaces); if the pin count is over 32, there is probably a JTAG option.

- Almost all FPGAs and CPLDs used today can be programmed via a JTAG port. A Standard Test and Programming Language is defined by JEDEC standard JESD-71 for JTAG programming of PLD's.

- Multiple MIPS and PowerPC processors have JTAG support

- Intel Core, Xeon, Atom, and Quark processors all support JTAG probe mode with Intel-specific extensions of JTAG using the so-called 60-pin eXtended Debug Port [XDP]. Additionally, the Quark processor supports more traditional 10-pin connectors.

- Consumer products such as networking appliances and satellite television integrated receiver/decoders often use microprocessors that support JTAG, providing an alternate means to reload firmware if the existing bootloader has been corrupted in some manner.

- The PCI bus connector standard contains optional JTAG signals on pins 1–5;[18] PCI Express contains JTAG signals on pins 5–9.[19] A special JTAG card can be used to reflash a corrupt BIOS.

- Boundary scan testing and in-system (device) programming applications are sometimes programmed using the Serial Vector Format, a textual representation of JTAG operations using a simple syntax. Other programming formats include 'JAM' and STAPL plus more recently the IEEE Std. 1532 defined format 'ISC' (short for In-System Configuration). ISC format is used in conjunction with enhanced BSDL models for programmable logic devices (i.e. FPGAs and CPLDs) that include additional ISC_<operation> instructions in addition to the basic bare minimum IEEE 1149.1 instructions. FPGA programming tools from Xilinx, Altera, Lattice, Cypress, Actel, etc. typically are able to export such files.

- As mentioned, a number of boards include JTAG connectors, or just pads, to support manufacturing operations, where boundary scan testing helps verify board quality (identifying bad solder joints, etc.) and to initialize flash memory or FPGAs.

- JTAG can also support field updates and troubleshooting.

Client support

[edit]The target's JTAG interface is accessed using some JTAG-enabled application and some JTAG adapter hardware. There is a wide range of such hardware, optimized for purposes such as production testing, debugging high-speed systems, low cost microcontroller development, and so on. In the same way, the software used to drive such hardware can be quite varied. Software developers mostly use JTAG for debugging and updating firmware.

Connectors

[edit]

There are no official standards for JTAG adapter physical connectors. Development boards usually include a header to support preferred development tools; in some cases, they include multiple such headers because they need to support multiple such tools. For example, a microcontroller, FPGA, and ARM application processor rarely share tools, so a development board using all of those components might have three or more headers. Production boards may omit the headers, or when space is limited may provide JTAG signal access using test points.

Some common pinouts[20] for 2.54 mm (0.100 in) pin headers are:

- ARM 2×10 pin (or sometimes the older 2×7), used by almost all ARM-based systems

- MIPS EJTAG (2×7 pin) used for MIPS based systems

- 2×5 pin Altera ByteBlaster-compatible JTAG extended by multiple vendors

- 2×5 pin AVR extends Altera JTAG with SRST (and in some cases TRST and an event output)

- 2×7 pin Texas Instruments used with DSPs and ARM-based products such as OMAP

- 8 pin (single row) generic PLD JTAG compatible with multiple Lattice ispDOWNLOAD cables

- MIPI10-/20-connectors (1.27 mm 050") for JTAG, cJTAG and SWD

Those connectors tend to include more than just the four standardized signals (TMS, TCK, TDI, TDO). Usually reset signals are provided, one or both of TRST (TAP reset) and SRST (system reset). The connector usually provides the board-under-test's logic supply voltage so that the JTAG adapters use the appropriate logic levels. The board voltage may also serve as a board present debugger input. Other event input or output signals may be provided, or general purpose I/O (GPIO) lines, to support more complex debugging architectures.

Higher end products frequently use dense connectors (frequently 38-pin MICTOR connectors) to support high-speed tracing in conjunction with JTAG operations. A recent trend is to have development boards integrate a USB interface to JTAG, where a second channel is used for a serial port. (Smaller boards can also be powered through USB. Since modern PCs tend to omit serial ports, such integrated debug links can significantly reduce clutter for developers.) Production boards often rely on bed-of-nails connections to test points for testing and programming.

Adapter hardware

[edit]Adapter hardware varies widely. When not integrated into a development board, it involves a short cable to attach to a JTAG connector on the target board; a connection to the debugging host, such as a USB, PCI, or Ethernet link; and enough electronics to adapt the two communications domains (and sometimes provide galvanic isolation). A separate power supply may be needed. There are both dumb adapters, where the host decides and performs all JTAG operations; and smart ones, where some of that work is performed inside the adapter, often driven by a microcontroller. The smart adapters eliminate link latencies for operation sequences that may involve polling for status changes between steps, and may accordingly offer higher throughput.

As of 2018[update], adapters with a USB link from the host are the most common approach. Higher-end products often support Ethernet, with the advantage that the debug host can be quite remote. Adapters that support high-speed trace ports generally include several megabytes of trace buffer and provide high-speed links (USB or Ethernet) to get that data to the host.

Parallel port adapters are simple and inexpensive, but they are relatively slow because they use the host CPU to change each bit ("bit banging"). They have declined in usefulness because most computers in recent years don't have a parallel port. Driver support is also a problem because pin usage by adapters varied widely. Since the parallel port is based on 5V logic level, most adapters lacked voltage translation support for 3.3V or 1.8V target voltages.

RS-232 serial port adapters also exist and are similarly declining in usefulness. They generally involve either slower bit banging than a parallel port, or a microcontroller translating some command protocol to JTAG operations. Such serial adapters are also not fast, but their command protocols could generally be reused on top of higher-speed links.

With all JTAG adapters, software support is a basic concern. Some vendors do not publish the protocols used by their JTAG adapter hardware, limiting their customers to the tool chains supported by those vendors. This is a particular issue for "smart" adapters, some of which embed significant amounts of knowledge about how to interact with specific CPUs.

Software development

[edit]Most development environments for embedded software include JTAG support. There are, broadly speaking, three sources of such software:

- Chip vendors may provide the tools, usually requiring a JTAG adapter they supply. Examples include FPGA vendors such as Xilinx and Altera, Atmel for its AVR8 and AVR32 product lines, and Texas Instruments for most of its DSP and micro products. Such tools tend to be highly featured and may be the only real option for highly specialized chips like FPGAs and DSPs. Lower-end software tools may be provided free of charge. The JTAG adapters themselves are not free, although sometimes they are bundled with development boards.

- Tool vendors may supply them, usually in conjunction with multiple chip vendors to provide cross-platform development support. ARM-based products have a particularly rich third-party market, and a number of those vendors have expanded to non-ARM platforms like MIPS and PowerPC. Tool vendors sometimes build products around free software like GCC and GDB, with GUI support frequently using Eclipse. JTAG adapters are sometimes sold along with support bundles.

- Open source tools exist. As noted above, GCC and GDB form the core of a good toolchain, and there are GUI environments to support them.

All such software tends to include basic debugger support: stopping, halting, single stepping, breakpoints, data structure browsing, and so on. Commercial tools tend to provide tools like very accurate simulators and trace analysis, which are not currently available as open source.

Similar interface standards

[edit]Serial Wire Debug (SWD) is an alternative 2-pin electrical interface that uses the same protocol. It uses the existing GND connection. SWD uses an ARM CPU standard bi-directional wire protocol, defined in the ARM Debug Interface v5.[21] This enables the debugger to become another AMBA bus master for access to system memory and peripheral or debug registers. Data rate is up to 4 MB/s at 50 MHz. SWD also has built-in error detection. On JTAG devices with SWD capability, the TMS and TCK are used as SWDIO and SWCLK signals, providing for dual-mode programmers.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Neal Stollon (2011). On-Chip Instrumentation. Springer.

- ^ Randy Johnson, Steward Christie (Intel Corporation, 2009), JTAG 101—IEEE 1149.x and Software Debug

- ^ Copies of IEEE 1149.1-1990 or its more recent updates (2001 and 2013, respectively) may be bought from the IEEE.

- ^ a b "IEEE 1149.1-2001". Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- ^ "IEEE 1149.1-2013".

- ^ Select the right FPGA debug method Archived 27 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine presents one of the models for such tools.

- ^ "FAQ: Under what conditions can I daisy-chain JTAG?". www.jtagtest.com.

- ^ a b c Texas Instruments is one adopter behind this standard and has an IEEE 1149.7 wiki page Archived 6 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine with more information.

- ^ "Major Benefits of IEEE 1149.7". Archived from the original on 12 February 2019.

- ^ Oshana, Rob (29 October 2002). "Introduction to JTAG". Embedded Systems Design. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ ARM1136JF-S and ARM1136J-S Technical Reference Manual revision r1p5, ARM DDI 0211K. Chapter 14 presents the Debug TAP. Other ARM11 cores present the same model through their Debug TAPs.

- ^ Documentation for the OMAP2420 is not publicly available. However, a Texas Instruments document The User's Guide to DBGJTAG Archived 31 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine discussing a JTAG diagnostic tool presents this OMAP2420 scan chain example (and others).

- ^ See "i.MX35 (MCIMX35) Multimedia Applications Processor Reference Manual" from the Freescale website. Chapter 44 presents its "Secure JTAG Controller" (SJC).

- ^ ARM9EJ-S Technical Reference Manual revision r1p2. Appendix B "Debug in Depth" presents the EmbeddedICE-RT module, as seen in the popular ARM926ejs core.

- ^ "CoreSight Components Technical Reference Manual: 2.3.2. Implementation specific details". infocenter.arm.com.

- ^ AN1817/D, "MMC20xx M•CORE OnCE Port Communication and Control Sequences"; Freescale Semiconductor, Inc.; 2004. Not all processors support the same OnCE module.

- ^ AN2073 "Differences Between the EOnCE and OnCE Ports"; Freescale Semiconductor, Inc.; 2005.

- ^ "PCI Local Bus Technical Summary, 4.10 JTAG/Boundary Scan Pins". Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ "Serial PCI Express Bus 16x Pinout and PCIe Pin out Signal names". www.interfacebus.com.

- ^ JTAG Pinouts lists a few JTAG-only header layouts that have widespread tool support.

- ^ "ARM Information Center". infocenter.arm.com. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

External links

[edit]- IEEE Standard for Reduced-Pin and Enhanced-Functionality Test Access Port and Boundary-Scan Architecture The official IEEE 1149.7 Standard.

- JTAG 101 - IEEE 1149.x and Software Debug at the Wayback Machine (archived 2014-04-06), Intel whitepaper on JTAG usage in system software debug across a wide range of architectures.

- IEEE Std 1149.1 (JTAG) Testability Primer Includes a strong technical presentation about JTAG, with design-for-test chapters.

- Boundary Scan / IEEE 1149 tutorial including details of variants of the IEEE standard, BSDL, DFT, and other topics

- JTAG Tutorial Useful tutorials and information on JTAG technology.

- What is JTAG? Useful information on JTAG, timeline, architecture and more.

- JTAG Applications JTAG for product development, life cycle, testing, tools needed, and other topics.

History

Origins in the 1980s

In the mid-1980s, the electronics industry faced significant challenges in testing printed circuit boards (PCBs) due to the rapid increase in IC density and complexity, particularly with multi-layer boards and shrinking pin spacings that rendered traditional bed-of-nails probing methods unreliable and costly.[8] To address these limitations, a consortium of European companies formed the Joint European Test Action Group (JETAG) in 1985, aiming to develop a standardized approach for verifying designs and testing assembled PCBs without relying on physical probes. This initiative was driven by the need for a more efficient, non-invasive testing strategy that could handle the evolving demands of high-density electronics manufacturing.[9] In 1986, JETAG expanded to incorporate North American participants and was renamed the Joint Test Action Group (JTAG), reflecting broader international collaboration among key players such as Philips, which initiated the effort within its European operations, Texas Instruments, and test equipment firms like GenRad.[10] The group's early focus centered on pioneering serial scan paths for boundary testing, which would allow test data to be shifted through IC boundaries via a dedicated interface, thereby replacing direct physical access with a serial protocol to detect interconnect faults on PCBs.[11] This conceptual shift promised to reduce testing complexity and costs while improving fault coverage in dense assemblies.[8] The inaugural JTAG meetings took place between 1986 and 1987, including discussions at events like the International Test Conference (ITC) in 1987, where proposals for a standardized Test Access Port (TAP) were refined to serve as the core interface for IC test logic. These sessions emphasized a unified architecture featuring a serial input/output mechanism controlled by clock and mode signals, laying the foundation for interoperable boundary-scan capabilities across devices from multiple vendors.[8] By 1988, the JTAG Technical Subcommittee had advanced these ideas into formal proposals, setting the stage for eventual IEEE adoption.Standardization and Evolution

The Joint Test Action Group (JTAG) technology was formally standardized by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) as IEEE Std 1149.1-1990, which defined the Test Access Port (TAP) and boundary-scan architecture to enable testing of digital integrated circuits and printed circuit boards without physical probes.[12][13] Approved in 1990, this initial standard established a serial interface with dedicated pins for test data input (TDI), test data output (TDO), test mode select (TMS), and test clock (TCK), optionally including a test reset (TRST), to support interconnection testing and internal device diagnostics.[14][12] Subsequent revisions addressed evolving needs in semiconductor design. The IEEE Std 1149.1-2001 update introduced software-controlled test features, enhancing flexibility for maintenance and support functions while maintaining compatibility with the 1990 version.[15] A more substantial overhaul occurred with IEEE Std 1149.1-2013, which incorporated optional features such as the procedural description language (PDL) for documenting test procedures and extensions to the boundary-scan description language (BSDL) to handle complex tests in heterogeneous integrated circuits.[16][17] These 2013 enhancements, approved after a decade of development, doubled the standard's size and focused on test reuse for embedded cores via integration with IEEE 1500.[18] Recent advancements include the IEEE Std 1149.7-2022, known as cJTAG, which provides a reduced-pin variant of the TAP while ensuring full backward compatibility with IEEE 1149.1 implementations.[19] Published on October 14, 2022, this standard defines six TAP classes (T0 to T5) with incremental capabilities, such as two-wire operation to minimize pin usage in space-constrained systems.[20] These evolutions have been driven by increasing system-on-chip (SoC) complexity, the proliferation of embedded instrumentation for in-system diagnostics, and the demand for reduced pin counts in high-density designs.[17] As of 2023, the IEEE 1149.1 working group has been discussing a potential refresh, aligning with approximate 10-year revision cycles to incorporate further adaptations for advanced packaging and internal scan networks.[21]Technical Fundamentals

Electrical Characteristics

The JTAG interface is implemented through a Test Access Port (TAP) that typically consists of four mandatory pins: TCK for providing the test clock signal, TMS for selecting operational modes, TDI for serial data input, and TDO for serial data output. An optional fifth pin, TRST, can be included to asynchronously reset the TAP controller.[22][23][24] Signal voltage levels for the TAP pins are not rigidly defined by the IEEE 1149.1 standard but must comply with the device's I/O characteristics, commonly aligning with CMOS or TTL logic families operating at 1.2 V to 5 V based on the system supply voltage (Vcc). For boundary-scan testing, pins support specific compliance patterns such as high-impedance (high-Z) states to isolate the device from the board, as well as weak pull-up or pull-down configurations to detect open or short faults during pin integrity checks.[25][26][2] In multi-device systems, the daisy-chain topology connects devices serially by routing the TDO output of one device to the TDI input of the next, with TMS and TCK signals bused in parallel to all devices for synchronized control. This arrangement enables efficient scanning across chains but imposes requirements on signal integrity, including controlled impedance traces (often 50 Ω characteristic impedance) to reduce reflections and support TCK frequencies up to 100 MHz, limited by factors such as chain length, capacitive loading, and individual device timing specifications.[2][24] JTAG TAP operation relies on the device's system power supply (Vcc) without a dedicated power pin, ensuring that signal levels track the core voltage for compatibility. ESD protection guidelines for JTAG pins follow general semiconductor practices, with integrated circuits typically rated for at least 2 kV human body model (HBM) resilience, and external interfaces recommended to include series resistors (e.g., 100–220 Ω on data lines) and proper grounding to mitigate electrostatic discharge risks during handling and connection.[28][29]Communications Primitives

The JTAG communications primitives are defined by the Test Access Port (TAP) controller, a 16-state finite state machine that orchestrates all operations within the IEEE 1149.1 standard.[30] The states include Test-Logic-Reset, Run-Test/Idle, Select-DR-Scan, Capture-DR, Shift-DR, Exit1-DR, Pause-DR, Exit2-DR, Update-DR, Select-IR-Scan, Capture-IR, Shift-IR, Exit1-IR, Pause-IR, Exit2-IR, and Update-IR.[30] Transitions between these states are controlled by the Test Mode Select (TMS) signal, which is sampled on the rising edge of the Test Clock (TCK); a TMS value of 1 directs the machine toward the instruction register path or reset, while 0 follows the data register path or stable modes.[31] This synchronous design ensures deterministic behavior, with the state machine starting in Test-Logic-Reset upon power-up or reset.[30] Data transfer in JTAG relies on serial shifting during the Shift-DR and Shift-IR states, where bits are loaded into the selected register via the Test Data In (TDI) pin and simultaneously shifted out through the Test Data Out (TDO) pin.[30] Each rising edge of TCK advances the shift by one bit, forming a daisy-chain scan path that allows external tools to load or read register contents bit by bit without parallel access.[31] The instruction register (IR) is selected by navigating the TMS path through Select-IR-Scan, Capture-IR, and into Shift-IR, where commands like BYPASS or SAMPLE are loaded; conversely, the data register (DR) path—via Select-DR-Scan, Capture-DR, and Shift-DR—handles operand data for the active instruction, such as boundary-scan chain contents.[30] Fundamental primitives include reset and idle operations to initialize or pause JTAG activity. Reset can be achieved asynchronously via an optional Test Reset (TRST) pin or synchronously by holding TMS high for at least five rising TCK edges, forcing the TAP into Test-Logic-Reset and disabling test logic.[30] The Run-Test/Idle state serves as the primary idle mode, where the system remains stable with no shifting or capturing, allowing time for internal test operations or waiting for host commands; entry to this state occurs from Update-DR or Update-IR with TMS low.[31] Timing for these primitives emphasizes reliable signal integrity relative to TCK. TMS and TDI must meet setup time requirements—typically the minimum duration they must be stable before the rising TCK edge—to ensure correct sampling, and hold time—the duration after the rising edge—to prevent glitches.[2] TDO, in contrast, updates its value on the falling TCK edge, providing a half-cycle for propagation without interfering with input sampling.[2] This serial scanning flow conceptually involves clocking a stream of bits through the TAP, with the external controller managing TMS sequences to route data precisely through IR or DR paths while TCK provides the rhythmic pulse.[31]Core Standards

IEEE 1149.1 Boundary Scan

The IEEE 1149.1 standard establishes the foundational boundary-scan architecture for embedded test logic in integrated circuits, enabling standardized testing of interconnections between devices on assembled printed circuit boards without requiring physical access to individual pins. This architecture incorporates a Test Access Port (TAP) with four or five dedicated pins (TDI, TDO, TCK, TMS, and optionally TRST) to control a serial scan path that facilitates controllability and observability of I/O signals. By integrating shift-register cells adjacent to each device pin, the standard allows test stimuli to be applied and responses to be captured electronically, addressing the challenges of testing high-density boards where traditional bed-of-nails probing becomes impractical.[16] At the core of this architecture is the boundary-scan chain, composed of latch cells forming a shift register at every input, output, bidirectional, and control pin of the device. Each cell typically includes a boundary input cell for capturing incoming signals, a boundary output cell for driving outgoing signals, and additional logic for handling bidirectional or powered pins, ensuring that the chain provides full visibility and control over external interfaces. This setup permits the injection of test patterns to detect opens, shorts, and stuck-at faults in inter-device wiring, while the cells can be configured to support normal functional operation when not in test mode. The Boundary Scan Description Language (BSDL), defined within the standard, provides a standardized VHDL-based format for describing the chain's configuration, including cell types, port mappings, instruction codes, and register lengths, which is essential for interoperability and automated test vector generation across vendors.[32][2] The standard mandates specific registers to manage test operations: the Instruction Register (IR), a serial shift register of at least 2 bits (typically 4 to 8 bits in practice), which holds the opcode to select the active test mode or data register; and the Data Registers (DR), a family of selectable shift registers including the primary Boundary Scan Register (BSR) that spans the entire boundary chain. Other DRs may include bypass, identification, or user-defined registers, but the BSR is central, with its length determined by the number of pins and cell types (e.g., one cell per simple I/O, two for bidirectional). In a multi-device daisy chain, the full scan path length for BSR operations is the sum of individual BSR lengths plus any intervening fixed cells, allowing sequential shifting of data across the board-level chain without parallel access needs.[2][16] IEEE 1149.1 requires four public instructions to ensure basic compliance, each decoded from the IR to connect a specific DR to the TAP for shifting. The EXTEST instruction selects the BSR to drive test data from its output cells to external pins while capturing external signals into input cells, enabling comprehensive board-level interconnect testing by suspending internal device logic. The SAMPLE/PRELOAD instruction also connects the BSR but maintains the device in functional mode, allowing real-time sampling of pin states for signature analysis or preloading of test vectors into output cells without disrupting system operation. The BYPASS instruction selects a single-bit bypass DR, effectively shortening the scan chain by routing TDI directly to TDO and isolating the device, which is crucial for focusing tests on specific components in a chain. The IDCODE instruction selects a 32-bit identification register containing manufacturer ID, part number, version, and compliance codes, facilitating device discovery and configuration during test setup.[2][33] Beyond these, the standard defines several optional public instructions to extend functionality. The RUNBIST instruction connects a self-test data register, initiating an internal built-in self-test (BIST) sequence and returning pass/fail status via the BSR or another register, supporting at-speed internal diagnostics. The CLAMP instruction uses the BSR to force output and bidirectional pins to predefined safe states (e.g., high-impedance or logic levels) without shifting further data, useful for isolating faults during testing. The 2013 revision of IEEE 1149.1 introduced the Procedural Description Language (PDL), an optional Tcl-based extension to BSDL, for specifying complex, parameterized test sequences and register behaviors associated with new instructions like CLAMP_HOLD and ECIDCODE, enhancing documentation and reuse for advanced applications such as IP core integration. As of March 2024, IEEE 1149.1-2013 is designated as an Inactive-Reserved standard, meaning it remains valid but is no longer actively maintained.[2][34][16]IEEE 1149.7 Reduced-Pin Variant

The IEEE 1149.7 standard, also known as cJTAG, defines a reduced-pin and enhanced-functionality Test Access Port (TAP) and boundary-scan architecture that minimizes the number of dedicated pins required for test and debug access while maintaining compatibility with the IEEE 1149.1 standard.[19] It introduces circuitry to access on-chip TAPs using either the traditional four- or five-wire IEEE 1149.1 interface or a two-pin configuration aligned with the Serial Wire Debug (SWD) protocol, enabling efficient operation in pin-limited environments.[20] This variant supports mode detection to ensure backward compatibility, allowing devices to operate in full IEEE 1149.1 mode when connected to legacy systems.[19] A key feature of IEEE 1149.7 is its two-pin mode, which utilizes only the System Clock (SCK, equivalent to SWCLK) and System Data (SDI, equivalent to SWDIO) pins for all signaling, eliminating the need for separate Test Data In (TDI) and Test Data Out (TDO) pins.[20] This mode serializes IEEE 1149.1 transactions over the two pins, with protocol enhancements that detect the interface type at startup and switch accordingly to prevent conflicts with traditional JTAG chains.[19] In two-pin operation, control and data are multiplexed on the SDI pin, while SCK provides the timing reference, supporting both scan-based boundary testing and debug functions without additional I/O overhead.[35] The standard defines six hierarchical compliance classes (T0 through T5), each building on the previous to add incremental capabilities. Class T0 ensures full behavioral compatibility with IEEE 1149.1, particularly for multi-TAP devices, by emulating standard JTAG startup sequences.[19] Class T1 extends this with common debug instructions and power management features, such as selective TAP enabling to reduce quiescent current.[20] Class T2 introduces high-performance scan modes, including optimized packet formats for faster data transfer in daisy-chain topologies.[35] Class T3 supports flexible four-wire configurations in either series or star scan topologies, enabling efficient multi-device addressing.[19] Classes T4 and T5 enable the two-pin interface, with T4 providing basic serialization and T5 adding advanced credit-based flow control for reliable, high-bandwidth non-scan data transfers across multiple on-chip clients.[20] The 2022 revision of IEEE 1149.7 enhances integration with SWD by formalizing the two-pin access as a native pathway for both test and debug, including refined protocols for seamless protocol switching in mixed environments. It improves timing parameters to support higher clock rates suitable for modern systems and extends multi-device chain support through enhanced topology handling in classes T2 and T3, facilitating daisy-chain and star configurations with reduced latency.[20] These updates address evolving challenges in debug and test systems, such as those in stacked-die and system-on-chip designs.[19] Advantages of IEEE 1149.7 include significant reduction in I/O pin count, which is particularly beneficial for space-constrained applications like wearables and mobile devices, where traditional five-pin JTAG would consume valuable resources.[35] The credit-based flow control in Class T5 ensures efficient data handling by managing buffer overflows in high-speed, multi-client scenarios, improving overall system reliability without increasing pin usage.[20] Overall, the standard balances pin efficiency with enhanced performance, making it a scalable solution for advanced integrated circuits.[19]Advanced Extensions

Internal JTAG (IEEE 1687)

IEEE 1687, commonly referred to as Internal JTAG or IJTAG, is a standard developed by the IEEE for providing standardized access and control to embedded instrumentation within semiconductor devices. Published in 2014, it builds upon the foundational IEEE 1149.1 (JTAG) boundary-scan architecture by extending the test access port (TAP) to support hierarchical networks of internal instruments, such as logic analyzers, performance monitors, and debug registers, without specifying the instruments themselves.[36] The primary purpose is to enable efficient reuse of embedded test and measurement IP across design flows, facilitating post-silicon validation, debug, and at-speed testing in complex system-on-chips (SoCs) where traditional boundary-scan alone is insufficient for internal visibility.[37] This standard addresses the growing complexity of integrated circuits by allowing instrument networks to be described portably, promoting interoperability among tools from different vendors.[38] At its core, IEEE 1687 introduces two key description languages: the Instrument Connectivity Language (ICL) and the Procedure Description Language (PDL). ICL defines the structural topology of the instrument network, including interconnections between the JTAG TAP, scan segments, and instruments, using a modular, hierarchical approach that supports retargeting for IP reuse.[39] PDL, on the other hand, specifies operational procedures for instruments, such as read/write operations or capture sequences, in a vendor- and tool-independent manner. To optimize access in potentially large networks, the standard employs Segment Insertion Bits (SIBs), which are configurable bits that dynamically insert or bypass scan path segments, reducing test time and data volume by avoiding unnecessary scanning through inactive branches.[21] This retargeting mechanism allows the same instrument description to be adapted to different TAP configurations or hierarchical levels, such as from die-level to package-level integration.[40] The architecture integrates seamlessly with IEEE 1149.1 by reusing the TAP controller, TMS, and TCK signals, but augments the instruction register and data registers to include internal scan chains. For example, a typical IJTAG network might route from the boundary-scan chain to an internal Module (a container for instruments) via a Wire-AND or other interconnect primitives, with SIBs enabling selective activation.[41] Compliance requires devices to support optional instructions like EXTEST_INSTR for internal access, ensuring backward compatibility with legacy JTAG tools while enabling advanced features like at-speed instrument operation. Extensions in later amendments, such as IEEE 1687.1-2025, further expand applicability to multi-die systems and 3D ICs, enhancing scalability for emerging heterogeneous integrations.[42] Overall, IEEE 1687 has become essential for modern SoC design, with adoption in industries like automotive and aerospace for in-system debug and silicon lifecycle management.[37]Auxiliary Standards (IEEE 1149.8 and Beyond)

IEEE 1149.8.1-2012 defines boundary-scan-based stimulus of interconnections to passive and/or active components. This standard codifies testability circuitry added to integrated circuits (ICs) incremental to IEEE 1149.1 provisions, enabling the use of boundary-scan to provide stimulus and response for testing components such as capacitors, resistors, and other passives on printed circuit boards without physical probes. It includes structural and procedural description languages to support loaded board testing and manufacturing defect detection.[43] Building on the core JTAG framework, several auxiliary standards address specific limitations in testing mixed-signal and high-speed environments. IEEE 1149.4, released in 1999, defines an analog boundary-scan architecture that extends digital boundary-scan to mixed-signal circuits, incorporating analog test receivers and sources to measure external components like capacitors and resistors on printed circuit boards. This standard introduces additional pins (AT1 and AT2) for analog stimulus and response, allowing non-intrusive testing of analog interconnects while maintaining compatibility with IEEE 1149.1 digital operations. Similarly, IEEE 1149.6, approved in 2003, targets AC-coupled and differential high-speed networks, which are incompatible with the DC-coupled assumptions of IEEE 1149.1. It specifies compliant digital pins and analog pins to handle signals like LVDS and SERDES, enabling EXTEST operations on advanced I/O without signal distortion, thus supporting testing of modern interconnects in multi-gigabit environments.[44][45] Security has become a critical aspect of JTAG implementations due to inherent vulnerabilities that expose devices to physical attacks. Unauthorized access via exposed JTAG ports can enable attackers with physical proximity to extract cryptographic keys, dump firmware, or manipulate internal states, as demonstrated in exploits targeting mobile devices and embedded systems. For instance, physical probing of JTAG pins has been used to bypass secure boot mechanisms and retrieve sensitive data from flash memory. To mitigate these risks, post-2013 countermeasures include TAP locking, which disables or restricts JTAG access through hardware fuses or configuration bits after initial testing, and encrypted scan chains that protect data shifted through TDI/TDO using stream ciphers like AES. Emerging work in the 2020s emphasizes authentication protocols, such as challenge-response mechanisms, to verify users before granting JTAG access, often integrated into SoC security controllers from vendors like NXP and Arm. These approaches balance testability with protection, ensuring JTAG remains viable for debugging while preventing unauthorized exploitation.[46][47][48][49] Recent developments in auxiliary standards focus on adapting JTAG for advanced packaging technologies, notably through integration with IEEE 1838. This 2019 standard establishes a test access architecture for three-dimensional (3D) stacked integrated circuits, incorporating per-die TAP controllers that leverage JTAG primitives for hierarchical control across stacked layers. In 3D ICs, IEEE 1838 enables pre-bond and post-bond testing by routing scan paths through micro-bumps and interposers, allowing individual die testing without full stack disassembly. Procedurally, it uses a serial network of TAPs to select and activate test modes on specific dies, combining with boundary-scan for interconnect verification and embedded instruments for functional validation, thus addressing yield challenges in heterogeneous 3D stacking.[50]Applications

Board-Level Testing

Boundary scan, as defined in the IEEE 1149.1 standard, enables testing of assembled printed circuit boards (PCBs) by accessing the interconnects between compliant devices without physical probes. The EXTEST instruction shifts the boundary scan register to control and observe the input/output pins of each device, allowing detection of opens, shorts, and other faults in the wiring between components. This method isolates the board's structural integrity by applying test patterns to one device's outputs while capturing responses at the next device's inputs in the scan chain.[33][2] Prior to full interconnect testing, chain integrity must be verified to ensure all devices are properly connected and responsive. The BYPASS instruction connects the test data in (TDI) and test data out (TDO) pins through a single-bit register in each device, enabling a quick check of the overall chain length and continuity by measuring the expected shift delay. The optional IDCODE instruction further confirms device presence and identity by reading a 32-bit manufacturer-specific code from each component, helping identify miswired or missing parts in the daisy-chain configuration.[51][52] Test vectors for interconnect faults typically include walking 1s and 0s patterns to detect stuck-at faults and bridges, where a logic 1 or 0 is propagated through each net sequentially to verify connectivity. For efficiency, signature analysis compresses responses using a multiple input signature register (MISR) to generate a compact fault signature, improving test speed while maintaining coverage. Automation relies on Boundary Scan Description Language (BSDL) files provided by device manufacturers, which describe the pin mappings, register lengths, and instruction opcodes to generate netlists and vectors for board-specific tests.[53][32] Compared to traditional bed-of-nails probing, boundary scan offers non-intrusive access ideal for ball-grid array (BGA) and surface-mount technology (SMT) packages, where physical probes are impractical due to dense pin spacing. It achieves high fault coverage, often exceeding 90% for digital nets in complex boards, reducing test fixture costs and enabling at-speed testing without custom hardware.[54][55][56] A key limitation is its dependence on JTAG-compliant components; non-compliant parts, such as analog devices or legacy ICs, cannot be directly tested, necessitating hybrid approaches that combine boundary scan with flying probe systems for full board coverage.Device Debugging and Programming

JTAG plays a pivotal role in embedded system debugging by providing direct access to device internals through the Test Access Port (TAP), enabling developers to control processor execution and inspect states without physical probing. This capability stems from extensions to the core IEEE 1149.1 standard, which originally focused on boundary-scan testing but was adapted by semiconductor vendors in the early 1990s to support functional debugging of microcontrollers. For instance, Intel's integration of JTAG-like features in the 80486 processor around 1990 marked an early milestone, allowing initial firmware debugging and in-system modifications that reduced reliance on socketed programming.[57] By the mid-1990s, JTAG had become a standard tool for microcontroller debugging, facilitating operations like single-stepping through code and memory examination on devices such as early ARM-based systems. In modern multi-core System-on-Chips (SoCs), JTAG extensions—such as those in IEEE 1149.7 for reduced-pin interfaces—enable scalable debugging across multiple processors, supporting simultaneous halt and trace operations to manage complexity in heterogeneous cores.[58][59] Debug access via JTAG typically involves private instructions, which are vendor-specific opcodes loaded into the Instruction Register (IR) to invoke non-standard behaviors beyond the mandatory BYPASS, EXTEST, and SAMPLE/PRELOAD instructions defined in IEEE 1149.1. These private instructions allow halting and resuming the CPU by shifting data into internal debug registers; for example, in ARM architectures, the HALT instruction sets a bit in the Debug Status and Control Register (DSCR) via the JTAG interface, pausing execution while preserving context for inspection. Trace ports, accessible through JTAG, further support instruction breakpoints by capturing execution flows without full halts, using embedded trace macros (ETMs) to stream data off-chip for analysis.[2][60][61] For firmware storage and updates, JTAG enables in-system programming (ISP) of non-volatile memories like flash and EEPROM, even when these components lack native JTAG support, by leveraging the host device's TAP to control programming signals. This often involves shifting configuration data into the device's control registers to initiate write cycles, as seen in CPLD and FPGA applications where JTAG sequences program configuration flash directly. A common technique is bootloader injection, where JTAG loads an initial bootloader into RAM, which then handles subsequent firmware updates to flash, streamlining field upgrades without dedicated programmers.[62][63] JTAG debugging employs two primary techniques: halt mode, which is invasive and stops the CPU entirely for detailed examination, and monitor mode, which is non-intrusive and allows real-time operation by invoking a debug monitor handler via interrupts. In halt mode, the processor enters a quiescent state upon JTAG command, enabling register reads/writes and breakpoint setting, but it disrupts timing-critical applications; this is ideal for low-level debugging of non-real-time systems. Conversely, monitor mode maintains essential functionality—such as peripheral servicing—while providing limited access through software-mediated JTAG requests, making it suitable for embedded real-time environments where full stops could cause system failures.[61][64] Despite its utility, JTAG introduces security risks, particularly through exposed debug features that can enable side-channel attacks. Private instructions may be reverse-engineered via scan chains, allowing unauthorized CPU control and data extraction, as demonstrated in scenarios where attackers insert malicious devices into JTAG chains to intercept or alter instructions. Additionally, JTAG ports facilitate power analysis side-channel attacks by modulating clock signals (TCK) to induce phase leakage, enabling inference of internal states like cryptographic keys without altering standard operations; such vulnerabilities have been shown to extract sensitive information from secure SoCs. To mitigate these, implementations often incorporate authentication or disablement mechanisms post-deployment.[65][66]Implementation and Tools

Hardware Interfaces and Connectors