Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

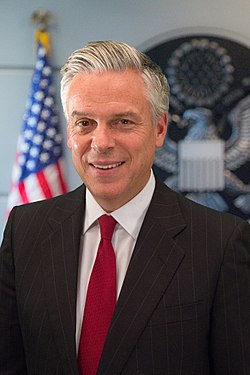

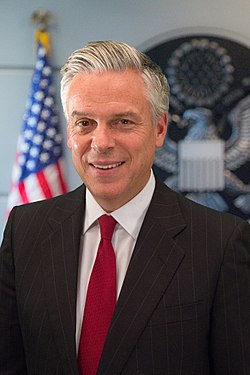

Jon Huntsman Jr.

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Governor of Utah

Presidential campaign

|

||

Jon Meade Huntsman Jr. (born March 26, 1960) is an American politician, businessman, and diplomat who served as the 16th governor of Utah from 2005 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the ambassador of the United States to Russia from 2017 to 2019, ambassador to China from 2009 to 2011, and ambassador to Singapore from 1992 to 1993.

Huntsman served in every presidential administration from the presidency of Ronald Reagan to the first Donald Trump administration. He began his career as a White House staff assistant for Ronald Reagan, and was appointed deputy assistant secretary of commerce and U.S. ambassador to Singapore by George H. W. Bush. Later as deputy U.S. trade representative under George W. Bush, he launched global trade negotiations in Doha in 2001 and guided the accession of China into the World Trade Organization. He was CEO of Huntsman Family Holdings, a private entity that held the stock the family owned in Huntsman Corporation. He was a board member of Huntsman Corporation, and as chair of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Huntsman is the only American ambassador to have served in both Russia and China,[1] having been the U.S. ambassador to China under Barack Obama from 2009 to 2011 and as the U.S. ambassador to Russia under Donald Trump from 2017 to 2019.

While governor of Utah, Huntsman was named chair of the Western Governors Association and joined the executive committee of the National Governors Association. Under his leadership, Utah was named the best-managed state in America by the Pew Center on the States.[2] During his tenure, Huntsman was one of the most popular governors in the country, and won reelection in a landslide in 2008, winning every single county. He left office with approval ratings over 80 percent and was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor Gary Herbert.[3] He was an unsuccessful candidate for the 2012 Republican presidential nomination.[4] He ran for governor again in 2020, but narrowly lost in the Republican primary to Lieutenant Governor Spencer Cox.[5]

Huntsman is a No Labels National Co-chair, and in July 2023, appeared with US senator Joe Manchin as headliners for a No Labels Common Sense Agenda Town Hall in Manchester, New Hampshire.[6] Huntsman is a member of the Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee, but in April 2025 he was dismissed along with the entire board by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth.[7]

Early life and education

[edit]Jon Meade Huntsman Jr. was born on March 26, 1960.[8] His father, Jon Huntsman Sr., was a business executive who later became a billionaire through the company he founded, the Huntsman Corporation, which achieved breakthrough success in the 1970s manufacturing generic styrofoam cartons for McDonald's and other fast food companies and by the 1990s was one of the largest petrochemical companies in the United States.[9] His mother is Karen (née Haight) Huntsman, daughter of David B. Haight, an apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).[10] Through his father, Huntsman is the great-great-great-grandson of early LDS Church leader Parley P. Pratt.[11]

In 1975, Huntsman earned the rank of Eagle Scout, the highest rank of the Boy Scouts of America.[12] He attended Highland High School in Salt Lake City but dropped out before graduating to perform as a keyboard player in a rock band.[13][14] Huntsman later obtained a G.E.D. and enrolled at the University of Utah, where he became a member of the Sigma Chi fraternity like his father. Jon Huntsman Jr. served as a missionary for the LDS Church in Taiwan for two years and later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with a bachelor of arts in international politics in 1987.

Political career

[edit]While Huntsman was visiting the White House in 1971 during his father's service as special assistant to U.S. president Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger confided to the eleven-year-old that he was secretly traveling to China.[15] Jon Huntsman Jr. worked as a White House staff assistant in Reagan administration in 1983. From 1987 to 1988, Huntsman and his family lived and worked in Taipei, Taiwan.[16]

Huntsman and Enid Greene Mickelsen were co-directors of Reagan's campaign in Utah.[17] During the 1988 presidential election, he was a state delegate at the 1988 Republican National Convention.[18]

George H. W. Bush administration

[edit]Under President George H. W. Bush, Huntsman was deputy assistant secretary in the International Trade Administration from 1989 to 1990.[16] He served as deputy assistant secretary of commerce for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, from 1990 to 1991.[16]

In June 1992, Bush appointed Huntsman as U.S. ambassador to Singapore,[19] and he was unanimously confirmed by the United States Senate in August.[20] At 32 years old, he became the youngest U.S. Ambassador to serve in over 100 years.[21][22]

George W. Bush administration

[edit]In January 2001, after George W. Bush took office as president, The Washington Post reported there was a strong possibility Huntsman would be appointed to be the new U.S. ambassador to China.[23] In March, Huntsman reportedly turned down the nomination to be the U.S. Ambassador to Indonesia.[24] On March 28, Bush appointed Huntsman to be one of two Deputy United States trade representatives in his administration;[25] he served in this role from 2001 to 2003.[16]

Governor of Utah

[edit]In March 2003, Huntsman resigned his post in the Bush administration. In mid-August, three-term incumbent governor Mike Leavitt, who Huntsman strongly supported, decided not to run for re-election in order to become EPA administrator in the Bush administration.[26][27][28] Shortly thereafter, Huntsman filed papers to run for Governor of Utah.[29] In the June 2004 Republican primary, Huntsman defeated State Representative Nolan Karras 66–34%.[30] In November 2004, Huntsman was elected with 58% of the vote, defeating Democratic Party nominee Scott Matheson Jr.[31] In 2008, Huntsman won re-election with 77.7% of the vote, defeating Democratic nominee Bob Springmeyer.[32]

Huntsman maintained high approval ratings as governor of Utah, reaching 90% approval at times. He left office with his approval ratings over 80%.[3][33][34] Utah was named the best managed state by the Pew Center on the States.[2] Following his term as governor, Utah was also named a top-three state to do business in.[35] The 2006 Cato Institute evaluation gave Huntsman an overall fiscal policy grade of "B"; the institute gave him an "A" on tax policy and an "F" on spending policy.[36]

Depending on the methodology used, Utah was either the top-ranked state or fourth-ranked state in the nation for job growth during Huntsman's tenure, with a rate of either 5.9% or 4.8% between 2005 and 2009.[37]

The Utah Taxpayers Association estimates that "tax cuts from 2005 to 2007 totaled $407 million." Huntsman proposed eliminating the corporate franchise tax for small businesses making less than $5 million. During his term as governor, he was successful in having Utah replace its progressive income tax with a top rate of 7%, with a flat tax of 5%; cut the statewide sales tax rate from 4.75% to 4.65% and sales tax on unprepared food from 4.70% to 1.75%; and raise motor vehicle registration fees. He proposed a 400% increase in cigarette taxes, but the measure was never signed into law. In 2008, he successively proposed tax credits for families purchasing their own health insurance, as well as income tax credits for capital gains and solar projects.[38]

During Huntsman's administration, the state budget rose from $8.28 to 11.57 billion.[39]

Huntsman supported cap and trade policies, and as governor, signed the Western Climate Initiative.[40] He also supported an increase in the federal minimum wage.[41] He also cut some regulations, including Utah's very strict alcohol laws.[42] In 2007, he signed into law the Parent Choice in Education Act, which he said was "the largest school-voucher bill to date in the United States. This massive school-choice program provides scholarships ranging from $500 to $3000 to help parents send their children to the private school of their choice. The program was open to all current public school children, as well as some children already in private school." The voucher law was later repealed in a public referendum.[43]

Huntsman was one of John McCain's earliest supporters in his 2008 presidential campaign.[44][45] Huntsman helped McCain campaign in New Hampshire and other early primary states and went with him to Iraq twice including over Thanksgiving in 2007.[46] At the 2008 Republican National Convention, Huntsman delivered a nominating speech for Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, the party's nominee for vice president.[47] Huntsman also helped raise more than $500,000 for McCain's 2008 presidential campaign.[48] Speaking about McCain's loss, Huntsman later observed, "We're fundamentally staring down a demographic shift that we've never seen before in America".[49]

Ambassador to China

[edit]

President Barack Obama nominated Jon Huntsman to serve as the United States Ambassador to China on May 16, 2009, noting his experience in the region and proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. His nomination was formally delivered to the Senate on July 6, 2009, and on July 23, 2009, he appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,[50] which favorably reported his nomination to the full Senate on August 4, 2009.[51] On August 7, 2009, the Senate unanimously confirmed Huntsman[52] and he formally resigned as governor of Utah and was sworn in as ambassador to China on August 11, 2009.[53] Huntsman arrived in Beijing on August 21, 2009, to begin his assignment, and he delivered his first press conference on August 22 after a meeting with Commerce Minister Chen Deming.[54]

In February 2011, Huntsman made a controversial appearance at the site of a planned pro-democracy protest in Beijing.[55] The spokesman for the U.S. Embassy in China stated that Huntsman had been unaware of the planned protest, and happened to be strolling through the area on a family outing.[56][57]

Huntsman resigned from his position as ambassador, effective April 30, 2011, in order to return to the United States to explore a 2012 presidential bid.

2012 presidential campaign

[edit]

Background

[edit]Huntsman's name appeared on lists of potential Republican nominees for the 2012 presidential election as early as 2008 and 2009,[58][59] and John McCain specifically mentioned Huntsman as a potential candidate for the 2012 election in March 2009.[60]

In August 2010, a group of political strategists close to Huntsman formed a political action committee called Horizon PAC.[61] On February 22, 2011, Horizon PAC launched its official website, stating that it "supports free-market values, principled leadership and a commitment to long-term solutions".[62]

Campaign

[edit]On January 31, 2011, Huntsman submitted his formal resignation from his post as U.S. Ambassador to China effective April 30, 2011, indicating his plans to return to the United States at that time.[63] Huntsman's associates indicated that he was likely to explore a 2012 Republican presidential bid.[64][65][66]

On May 3, 2011, he formed an official fundraising political action committee, building on the efforts of the previously established Horizon PAC.[67] On May 18, 2011, Huntsman opened his 2012 national campaign headquarters in Orlando, Florida. Huntsman formally entered the race for the Republican presidential nomination on June 21, 2011, announcing his bid in a speech at Liberty State Park in New Jersey, with the Statue of Liberty in the background—the same site where Ronald Reagan launched his campaign in 1980.[68][69]

Huntsman sought to establish himself as an anti-negative candidate and take the "high road". In his announcement, he also stated "I don't think you need to run down someone's reputation in order to run for the office of President."[70]

Huntsman focused his energy and resources on the New Hampshire primary. On October 18, 2011, he boycotted the Republican presidential debate in Las Vegas, out of deference to New Hampshire, which was locked in a political scheduling fight with Nevada.[71] Huntsman eventually finished third in New Hampshire, and announced the end of his campaign on January 16, 2012. He endorsed Mitt Romney at that time.[72]

Post-campaign politics

[edit]

A month after dropping out of the 2012 race, Huntsman suggested there was a need for a third party in the United States, stating that "the real issues [were] not being addressed, and it's time that we put forward an alternative vision." Huntsman said that he would not run as a third-party presidential candidate in 2012.[73] In early July, Huntsman announced that he would not be attending the 2012 Republican National Convention for the first time since he attended as a Reagan delegate in 1984; he stated he would "not be attending this year's convention, nor any Republican convention in the future until the party focuses on a bigger, bolder, more confident future for the United States—a future based on problem solving, inclusiveness, and a willingness to address the trust deficit, which is every bit as corrosive as our fiscal and economic deficits."[74]

Shortly after Obama's re-election, Obama's campaign manager Jim Messina admitted that the Obama campaign believed Huntsman would have been a particularly difficult candidate to defeat in the general election. Messina said that the campaign was "honest about our concerns about Huntsman" and that Huntsman "would have been a very tough candidate".[75]

In January 2014, Huntsman was named chairman of the Atlanticist think-tank the Atlantic Council.[76] Huntsman indicated in an interview with Politico that he would not run in the 2016 presidential election.[77]

In April 2016, Huntsman decided to endorse Republican nominee Donald Trump,[78] but later retracted his endorsement of Trump following the Access Hollywood controversy.[79] However, Huntsman later defended Trump in interviews with Fox News and The New York Times after Trump received criticism for accepting a congratulatory phone call with the president of Taiwan, Tsai Ing-wen, during his transition process.[80] Huntsman said the critics were overreacting to Trump's decision to accept the phone call, and that Trump's nontraditional style might be an opportunity for a shift in Asia relations in future talks with China.[80]

In November 2016, Huntsman said he was considering a run for the U.S. Senate in 2018, though he ultimately chose not to run for the seat.[81]

Huntsman was the co-chair of the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, along with Dennis C. Blair.[82] The commission is an independent and bipartisan initiative from the public and private sectors. Its mission is to document and assess the extent of international intellectual property theft, particularly by China, and propose appropriate policy responses. According to the commission's analysis, the U.S. has lost up to $600 billion in illicit technology transfers to China.[83] According to Huntsman,

The vast, illicit transfer of American innovation is one of the most significant economic issues impacting U.S. competitiveness that the nation has not fully addressed. It ... must be a top priority of the new administration [in 2016].[82]

Ambassador to Russia

[edit]On December 3, 2016, the Associated Press reported Huntsman was being considered by Donald Trump and the Trump transition team as a possible choice for United States Secretary of State in 2017,[80] although Rex Tillerson was chosen 10 days later.

On March 8, 2017, it was reported that Huntsman accepted a position as United States Ambassador to Russia.[84][85] During his Senate confirmation hearings, he said, "There is no question that the Russian Government interfered in the U.S. election" in 2016. He also said the relationship between the two countries was "among the most consequential and complex foreign policy challenges we face."[86] Huntsman was unanimously confirmed by the Senate, via voice vote, on September 28, 2017.[87][88]

During his time as ambassador, Huntsman reported having access to senior Russian officials, which he stated was not always the case during his ambassadorship to China. He also expressed a desire to avoid repeating past mistakes in the relationship, stating: "In the years past, every new administration has tried to reset or redo of some sort.(...) Let's not repeat the cycles of the past, because in every case,(...) those resets could not be sustained. Let's not even begin with that thought in mind; no resets, no redos. Just take the relationship for what it is, clear-eyed and realistically."[1]

Huntsman submitted his resignation as U.S. Ambassador to Russia to President Trump on August 6, 2019, with his resignation taking effect on October 3, 2019.[89][90] After Huntsman left post, Bartle B. Gorman, deputy ambassador to Russia, served as the embassy's Chargé d'Affaires[91] (until the arrival of John J. Sullivan as new ambassador).

2020 Utah gubernatorial campaign

[edit]After his resignation as U.S. ambassador to Russia in August 2019, many speculated that Huntsman was considering another run for Utah governor.[92] An October 2019 poll of likely Utah voters showed Huntsman as a favorite among several potential gubernatorial candidates.[93]

On November 14, 2019, Huntsman announced on KSL Radio that he would run for Governor of Utah in the 2020 election.[94] In the six weeks between Huntsman's announcement and the end of 2019, Huntsman's campaign raised $520,000, and visited all 29 Utah counties.[95]

His daughter, Abby Huntsman, announced in January 2020 that she would leave her position on The View to join his gubernatorial campaign as a senior advisor.[96] On February 7, 2020, Huntsman announced that Provo city mayor Michelle Kaufusi would be his gubernatorial running mate.[97] A poll taken among likely voters in February showed Huntsman leading the race with 32% support, while 31% remained undecided.[98] However, Lieutenant Governor Spencer Cox ultimately won the primary with 36.4% of the vote against Huntsman's 34.6%, and went on to win the general election.[99]

Political positions

[edit]Huntsman has been described as "a conservative technocrat-optimist with moderate positions who was willing to work substantively with President Barack Obama"[100] and identifies himself as a center-right conservative.[101]

During his first term as Utah governor, Huntsman listed economic development, healthcare reform, education, and energy security as his top priorities. He oversaw tax cuts and advocated reorganizing the way that services were distributed so that the government would not become overwhelmed by the state's fast-growing population.

Building a winning coalition to tackle the looming fiscal and trust deficits will be impossible [for Republicans] if we continue to alienate broad segments of the population. We must be happy warriors who refuse to tolerate those who want Hispanic votes but not Hispanic neighbors.

— Jon Huntsman Jr.[102]

Healthcare

[edit]During his time as Utah governor, Huntsman proposed a plan to reform healthcare, mainly through the private sector, by using tax breaks and negotiation to keep prices down.[103]

In 2007, when asked about a healthcare mandate, Huntsman said, "I'm comfortable with a requirement–you can call it whatever you want, but at some point we're going to have to get serious about how we deal with this issue". The healthcare plan that passed in Utah under Huntsman did not include a healthcare mandate.[104]

Fiscal policy

[edit]

In a 2008 evaluation of state governors' fiscal policies, the libertarian Cato Institute praised Huntsman's conservative tax policies, ranking him in a tie for fifth place on overall fiscal policy. He was particularly lauded for his efforts to cut taxes. The report specifically highlighted his reductions of the sales tax and simplification of the tax code.[105] However the report concluded that: "Unfortunately, Huntsman has completely dropped the ball on spending, with per capita spending increasing at about 10 percent annually during his tenure."[105] He defines his taxation policy as "business friendly".[106]

As part of his presidential campaign Huntsman said "our tax code has devolved into a maze of special-interest carve-outs, loopholes, and temporary provisions that cost taxpayers more than $400 billion a year to comply with". The candidate called for "[getting] rid of all tax expenditures, all loopholes, all deductions, all subsidies. Use that to lower rates across the board. And do it on a revenue-neutral basis".[107]

In addition, Huntsman has proposed reducing the corporate tax rate from 35% to 25%, eliminating corporate taxes on income earned overseas, and implementing a tax holiday to encourage corporations to return profits from offshore tax havens. He favored eliminating taxes on capital gains and dividends.[108]

Social issues

[edit]As the governor of Utah, Huntsman signed several bills placing limits on abortion.[109]

During the 2012 presidential race, and as governor of Utah, Huntsman supported civil unions for same-sex couples but not same-sex marriage.[110][111][112]

In a February 2013 op-ed published in The American Conservative, Huntsman updated his stance to one of support for same-sex marriage, stating: "All Americans should be treated equally by the law, whether they marry in a church, another religious institution, or a town hall. This does not mean that any religious group would be forced by the state to recognize relationships that run counter to their conscience. Civil equality is compatible with, and indeed promotes, freedom of conscience."[102][113] In 2013, Huntsman was a signatory to an amicus curiae brief submitted to the Supreme Court in support of same-sex marriage during the Hollingsworth v. Perry case.[112]

Environment and energy

[edit]In 2007, in response to the issue of global warming, Huntsman signed the Western Climate Initiative, by which Utah joined with other governments in agreeing to pursue targets for reduced production of greenhouse gases.[114] He also appeared in an advertisement sponsored by Environmental Defense, in which he said, "Now it's time for Congress to act by capping greenhouse-gas pollution."[114]

In 2011, in response to comments by Rick Perry and other Republican presidential candidates, Huntsman stated he "believe[s] in evolution and trust[s] scientists" on climate change.[115] Commenting later on his statement, Huntsman remarked "I felt that it was important to remind a lot of Republican voters who care and a lot of independent voters who care, that there is a candidate who does believe in science."[116]

Huntsman has stated a preference for international cooperation in handling climate change, stating "it's a global issue. We can enact policies here [in the United States], but I wouldn't want to unilaterally disarm as a country."[117]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Huntsman has repeatedly stated, "We need to continue working closely with China to convince North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program". He has also named Taiwan, human rights, and Tibet among the "areas where we have differences with China" and vowed "robust engagement" as ambassador. Huntsman, who lived in Taiwan as a Mormon missionary, said he felt "personally invested in the peaceful resolution of cross-strait differences, in a way that respects the wishes of the people on both Taiwan and the mainland. In 2009, he said that then-current U.S. policy "support[ed] this objective, and [he was] encouraged by the recent relaxing of cross-strait tensions."[118]

During his 2020 gubernatorial campaign, and after serving as Ambassador to Russia, Huntsman stated that "[the Russians] want to see us divided. They want to drive a wedge into politics... The American people do not understand the expertise at their disposal to divide us, to prey on our divisions. They take both sides of an issue to deepen the political divide. They are active during mass shootings. They are active during racial tension. They take advantage of us. We think it's fellow Americans who are taking extreme positions sometimes. It's not."[119]

Immigration

[edit]In 2005, Huntsman signed a bill giving undocumented migrants access to "driving-privilege cards", which allowed them to have driving privileges but unlike driver licenses, cannot be used for identification purposes. In a 2011 presidential debate, Huntsman defended the move, explaining that "[illegal immigrants] were given a driver's license before and they were using that for identification purposes. And I thought that was wrong. Instead we issued a driver privilege card, which in our state allowed our economy to continue to function. And it said in very bold letters, not to be used for identification purposes. It was a pragmatic local government driven fix and it proved that the Tenth Amendment works."[120]

In June 2007, Huntsman joined other Western governors in urging the Senate to pass comprehensive immigration reform.[121] As governor, Huntsman threatened to veto a measure repealing in-state college tuition for illegal immigrants.[122]

Huntsman has stated support for a border fence, saying that, "as an American, the thought of a fence to some extent repulses me ... but the situation is such that I don't think we have a choice".[123]

Huntsman supports granting more H-1B visas to foreigners.[124] Huntsman also supported the DREAM Act, which proposed a path to citizenship for young people brought to the United States by their parents illegally.[125]

Business career

[edit]From 1993 to 2001, Huntsman served as an executive for the Huntsman Corporation, chairman of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation, and CEO of Huntsman Family Holdings Company.

In January 2012, Huntsman Cancer Institute announced that Huntsman had been appointed to the position of chairman, replacing his father, who founded the institute.[126]

Huntsman was appointed to the board of directors of the Ford Motor Co. in February 2012. The announcement quoted Ford's executive chairman, William Clay Ford Jr., as praising Huntsman's global knowledge and experience—especially in Asia—as well as his tenure as the governor of Utah.[127] Huntsman was appointed to the board of Caterpillar Inc. in April 2012.[128]

From 2014 to 2017, and again from September 2020, Huntsman served on the board of directors of Chevron Corporation.[129]

Huntsman is a founding director of the Pacific Council on International Policy and has served on the boards of the Brookings Institution, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Asia Society in New York, and the National Bureau of Asian Research.

Personal life

[edit]Huntsman has eight brothers and sisters. He married activist Mary Kaye and they have seven children: daughters Mary Anne (b. 1985, who is married to Evan Morgan, son of CNN commentator Gloria Borger.[130]), Abigail (b. 1986), Elizabeth ("Liddy"; b. 1988), Gracie Mei (b. 1999; adopted from China), and Asha Bharati (b. 2006; adopted from India)[131] and sons Jon III (b. 1990), William (b. 1993), both of whom are graduates of the U.S. Naval Academy, and serving active duty assignments.

Huntsman is distantly related to 2012 Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney.[132][133][134] Their relationship has been reported to be one of rivalry. After a scandal erupted over the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Romney and Huntsman were both considered to take over the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the games. After intense lobbying, Romney was chosen, and the Huntsman family was reportedly "livid".[135] As Romney prepared his 2008 presidential run, he began consulting Huntsman on foreign policy and trade issues. Huntsman's father signed on as a finance chair for Romney's campaign, and it was expected that Huntsman would endorse Romney; instead, Huntsman backed John McCain and became one of the McCain campaign's national co-chairs.[135] Huntsman did endorse Romney in the 2012 election after dropping out.[135]

Huntsman is a self-proclaimed fan of the progressive rock genre and played keyboards during high school in the band Wizard.[136] Huntsman joined REO Speedwagon on the piano for two songs during their concert at the Utah State Fair in 2005. Huntsman is a fan of riding motocross, and he helped in pushing extreme sports and outdoor sports and tourism for the State of Utah.[137]

Huntsman has been awarded eleven honorary doctorate degrees,[138] including an honorary doctorate of public service from Snow College in 2005,[139] an honorary doctorate of science from Westminster College in 2008,[140] an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Utah in 2010,[141] an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Pennsylvania in 2010,[142] and an honorary doctorate of law from Southern New Hampshire University in 2011.[143] He also received honorary doctorates from the University of Washington, University of Arizona, Utah State University, and University of Wisconsin. He has been recognized as a Significant Sig by Sigma Chi.[144]

In 2007 Huntsman was awarded the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award by the BSA.[145] In October 2018, Huntsman was diagnosed with stage-1 melanoma and sought treatment at the Huntsman Cancer Institute.[146] On June 10, 2020, Huntsman announced that he had tested positive for COVID-19.[147][148][149]

Religious views

[edit]Huntsman is a member of the LDS Church and served a church mission to Taiwan. In an interview with Time magazine, he stated that he considers himself more spiritual than religious,[150][151] and in December 2010, he told Newsweek that the LDS Church doesn't have a monopoly on his spiritual life.[152] In a May 2011 interview, Huntsman said "I believe in God. I'm a good Christian. I'm very proud of my Mormon heritage. I am Mormon."[153]

Huntsman rejects the notion that faith and evolution are mutually exclusive. He said, "The minute that the Republican Party becomes . . . the anti-science party, we have a huge problem. We lose a whole lot of people who would otherwise allow us to win the election in 2012."[154]

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Spencer Cox | 190,565 | 36.15% | |

| Republican | Jon Huntsman Jr. | 184,246 | 34.95% | |

| Republican | Greg Hughes | 110,835 | 21.02% | |

| Republican | Thomas Wright | 41,532 | 7.88% | |

| Total votes | 527,178 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Jon Huntsman Jr. (incumbent) | 735,049 | 77.63% | +19.89% | |

| Democratic | Bob Springmeyer | 186,503 | 19.72% | −21.62% | |

| Libertarian | Dell Schanze | 24,820 | 2.62% | ||

| Write-ins | 153 | 0.02% | |||

| Majority | 547,546 | 57.91% | +41.51% | ||

| Turnout | 945,525 | ||||

| Republican hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Jon Huntsman Jr. | 531,190 | 57.74% | +1.97% | |

| Democratic | Scott Matheson Jr. | 380,359 | 41.35% | −0.92% | |

| Personal Choice | Ken Larsen | 8,399 | 0.91% | ||

| Write-ins | 12 | 0.00% | |||

| Majority | 150,831 | 16.40% | +2.89% | ||

| Turnout | 919,960 | ||||

| Republican hold | Swing | ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Ferris-Rotman, Amie; Tamkin, Emily; Gramer, Robbie (March 14, 2018). "Trump's Man in Moscow". Foreign Policy.

- ^ a b "The New Faces of the GOP New York Daily News". Daily News. May 11, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Huntsman, lawmakers' ratings soar". Deseret News. March 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (June 14, 2011). "Jon Huntsman 2012 presidential announcement coming June 21". Politico. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsman loses GOP primary in Utah". POLITICO. July 6, 2020.

- ^ Bowman, Bridget (July 12, 2023). "Joe Manchin and Jon Huntsman to headline No Labels town hall". NBC News. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Defense Policy Board". policy.defense.gov. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman Fast Facts". CNN. September 26, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2025.

- ^ "2-Min. Bio: Jon Huntsman: Obama's Nominee for Ambassador to China". Time. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Alumni and Friends Directory". Jon M. Huntsman School of Business. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (March 4, 2011). "Presidential hopefuls Huntsman, Romney share Mormonism and belief in themselves". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Carrie Mihalcik & Theresa Poulson (June 22, 2011). "10 Things You Can Call Jon Huntsman". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ "Interactive Timeline". Jon Huntsman For President. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Robert (May 1, 2011). "Jon Huntsman: A Political Path, Paved With Detours". NPR.

- ^ Liu, Melinda (November 15, 2009). "Obama's Man in China: Ambassador Jon Huntsman". Newsweek.

- ^ a b c d "Jon Huntsman Jr.", The New York Times, 2016, retrieved December 4, 2016

- ^ "Students work in trenches of Utah's political arena". The Daily Utah Chronicle. January 27, 1984. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Davidson, Lee; Bernick, Bob Jr. (August 16, 1988). "Rumors Project Huntsman into Position on Bush Cabinet". Deseret News. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "Huntsman Jr. Tapped As Envoy to Singapore". Deseret News. June 18, 1992. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Senate Panel OKs Utahn's Appointment". Deseret News. August 6, 1992. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Utah Governor Jon Huntsman Jr". Governor's Information. National Governors Association. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ "The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR JON M. HUNTSMAN, JR" (PDF). Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. February 25, 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "NewsLibrary.com - newspaper archive, clipping service - newspapers and other news sources". Nl.newsbank.com. January 26, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "NewsLibrary.com - newspaper archive, clipping service - newspapers and other news sources". Nl.newsbank.com. March 22, 2001. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Sahm, Phil (March 28, 2001). "The Salt Lake Tribune - Archives". Nl.newsbank.com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Swisher, Larry (August 15, 2003). "Bush picks Utah governor for EPA". Capital Press.

- ^ Harrie, Dan (August 18, 2003). "The Salt Lake Tribune - Archives". Nl.newsbank.com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "NewsLibrary.com - newspaper archive, clipping service - newspapers and other news sources". Nl.newsbank.com. March 30, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Huntsman Jr. files campaign papers". Deseret News. September 11, 2003. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "UT Governor - R Primary Race". Our Campaigns. June 22, 2004. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Utah election results 2004". The Washington Post. November 24, 2004.

- ^ "Huntsman still popular despite civil unions flap". Deseret News. February 17, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Are you ready for President Huntsman?". Hotair.com. January 3, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ McKay Coppins (January 1, 2011). "The Manchurian Candidate". Newsweek. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (October 2, 2009). "Best states for business". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "2012 Presidential White Paper #6". Club for Growth. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman says Utah was No. 1 in job creation when he was governor". PolitiFact. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Club for Growth whitepaper on Huntsman". Clubforgrowth.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "FY 2013-2014 Appropriations Report" (PDF). Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Kucinich, Jackie (June 21, 2011). "Huntsman's Utah record will face increased scrutiny". USA Today.

- ^ "Presidential White Papers: Jon Huntsman". Clubforgrowth.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Humphrey, Shawn (October 11, 2011). "Jon Huntsman's Economic Policy Focused on Governorship Experience". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Urbina, Ian (November 8, 2007). "Voters Split on Spending Initiatives on States' Ballots". The New York Times. United States; Pennsylvania; Maryland; Colorado; Georgia. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Sidoti, Liz (January 28, 2007). "Giuliani Stresses Vision and Performance". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Balz, Dan (February 25, 2007). "Governors See Influence Wane in Race for Presidency". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Huntsman goes to Iraq with McCain". Deseret News. November 20, 2007. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (February 3, 2011) When Huntsman hearted Palin, Politico

- ^ Beckel, Michael (June 18, 2009). "Obama's New Ambassador Nominees Gave Big – and Bundled Bigger". OpenSecrets.org. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (November 17, 2008). "Republicans ask: Just how bad is it?". Post-gazette.com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Gehrke, Robert (July 20, 2009). "Huntsman among 5 going before Senate committee". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ "Senate panel endorses Obama ambassadors to Japan, China". Agence France-Presse. August 4, 2009. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsman nomination gets unanimous Senate confirmation". Salt Lake City: KTVX. August 7, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Loomis, Brandon (August 11, 2009). "Huntsman out as guv, takes new post as ambassador". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Embassy of the United States Beijing, China". Archived from the original on October 13, 2005. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ Kenneth Tan (February 24, 2011). "Video of US Ambassador Jon Huntsman at 'Jasmine Revolution' protests in Beijing hits the Chinese interwebs". Shanghaiist. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Jeremy Page (February 23, 2011). "What's He Doing Here? Ambassador's Unusual Protest Cameo". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Jeremy Page (February 24, 2011). "After Protest Video, U.S. Envoy's Name Censored Online". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ Cheney says GOP presidential bench still strong, CNN June 29, 2009

- ^ "The Rising: Jon Huntsman Jr.", The Washington Post, December 9, 2008

- ^ "McCain: Let's see who runs in 2012". WTOP. Associated Press. March 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015.

- ^ Lisa Riley Roche (January 31, 2011). "White House says Huntsman leaving ambassadorship". Deseret News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Peter Hamby (February 22, 2011). "Pro-Huntsman effort launches website, offering 2012 clues". CNN. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "WH: Ambassador Huntsman To Leave China Post". Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Mike Allen (January 31, 2011). "Jon Huntsman resigns, may run". Politico. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ MJ Lee; Alexander Burns (January 31, 2011). "Gibbs confirms: Envoy is leaving". Politico. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Jonathan Martin; Alexander Burns (January 31, 2011). "Barack Obama braces for Jon Huntsman 2012 bid". Politico. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (May 3, 2011). "Jon Huntsman Takes Step Toward 2012 Bid". Politico. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman enters presidential race". Daily Telegraph. London. June 21, 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim (June 21, 2011). "Huntsman Announces Run for President". The New York Times. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsman Joins GOP 2012 Field, Touting Varied Resume, Hobbies (NewsHour Transcript)". PBS. June 21, 2011. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman Fast Facts". CNN.

- ^ Youngman, Sam (January 16, 2012). "Huntsman ends campaign, endorses Romney". Reuters. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ Bingham, Amy (February 23, 2012). "Jon Huntsman Calls for the Rise of a Third Party". ABC News. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Huntsman scolds GOP for losing focus, will skip convention". Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ "Obama Campaign Viewed Huntsman as 'Very Tough Candidate'". The Wall Street Journal. November 20, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ Howell, Tom. "Jon Huntsman tapped as Atlantic Council chairman". The Washington Times. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman says no thanks to 2016 run". Politico. October 8, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman adds to the growing list of GOP elite supporting Trump". AOL.com. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ "Utah Gov. Herbert and Rep. Chaffetz pull Trump endorsements, Huntsman says Trump should drop out after explicit video leaks". Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c Thomas Burr; Matthew Piper (December 3, 2016), "Jon Huntsman Jr.: Trump's 'nontraditional thinkin' could signal a new approach to U.S.-China relations", The Salt Lake Tribune, retrieved December 4, 2016

- ^ "Former Utah Governor Huntsman Considers U.S. Senate Run in 2018". Bloomberg.com. November 29, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Paul Wiseman. "Counterfeiters, hackers cost US up to $600 billion a year". stltoday.com. AP. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property". The National Bureau of Asian Research.

- ^ Savransky, Rebecca (March 8, 2017). "Huntsman accepts ambassadorship to Russia: report". The Hill. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Landler, Mark (March 9, 2017). "Jon Huntsman Is Said to Accept Post as Ambassador to Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Chalfant, Morgan (September 19, 2017). "Trump's pick for Russian ambassador: 'No question' Moscow interfered in US election". The Hill. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Romboy, Dennis. "Full Senate confirms Jon Huntsman Jr. as U.S. ambassador to Russia | KSL.com". KSL Salt Lake City. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Lardner, Richard (September 28, 2017). "Senate confirms Huntsman as US ambassador to Russia". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "Jon M. Huntsman Jr. (1960–)". Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman, U.S. ambassador to Russia, resigns to return to Utah for possible run for governor". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ "Chargé d'Affaires a.i. Bartle B. Gorman". U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Russia. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Burr, Thomas (August 6, 2019). "Jon Huntsman resigns as U.S. ambassador to Russia to return to Utah for possible run for governor". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ "Poll: Former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. favorite on list of possible candidates for governor". Deseret News.

- ^ Strauss, Daniel (November 14, 2019). "Jon Huntsman launches another run for Utah governor". POLITICO. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox raises $1.2 million in governor's race". Deseret News.

- ^ Brian Stelter and Oliver Darcy. "Abby Huntsman quits 'The View'". CNN. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman Jr. announces Provo mayor as his running mate". Daily Herald.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman, Spencer Cox leading GOP field in Utah governor's race". Deseret News. March 6, 2020.

- ^ "Utah GOP gubernatorial race called for Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox". www.deseret.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Linkins, Jason (February 11, 2011) "Jon Huntsman Staff Choice Suggests The Direction His Campaign Will Take", The Huffington Post

- ^ "Jon Huntsman: Does a 'center right' presidential candidate have a prayer?". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Huntsman, Jon (February 21, 2013). "Marriage Equality Is a Conservative Cause". The American Conservative. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ Parker, Kathleen (July 26, 2009). "Reforming Health Care Utah's Way Under Gov. Huntsman". The Washington Post.

- ^ Smith, Ben (May 31, 2011) "Huntsman was 'comfortable' with mandate". Politico.

- ^ a b Chris Edward (October 20, 2008). "Fiscal Policy Report Card on America's Governors: 2008" (PDF). Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 624.

- ^ Jon Huntsman, OnTheIssues

- ^ Parker, Ashley (August 31, 2011). "Huntsman Urges Stripping Deductions From Tax Code". The New York Times.

- ^ Huntsman 2012 website Archived November 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsman's pro-life credentials". YouTube. June 3, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Ambinder, Marc (February 13, 2009). "2012 And Huntsman's Surprise". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ Gehrke, Robert (May 11, 2010). "Huntsman's civil-union stance may prove political liability". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ a b Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (February 26, 2013). "Prominent Republicans Sign Brief in Support of Gay Marriage". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Levy, Pema (February 21, 2013). "Huntsman: Republicans Should Embrace Gay Marriage". TPM. Talking Points Memo. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Struglinski, Suzanne (November 16, 2007), "Huntsman appears in climate ad", Deseret News, archived from the original on August 3, 2011, retrieved June 6, 2011

- ^ Blake, Aaron (August 18, 2011). "Jon Huntsman believes in evolution and global warming, so can he win a Republican primary?". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman: The GOP's Lonely Climate Hawk". BuzzFeed News. January 15, 2013.

- ^ Strauss, Daniel (December 6, 2011). "Huntsman shifts stance on climate change". The Hill. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Hoklo-speaking diplomat aims for realistic PRC ties". The Taipei Times. July 29, 2009.

- ^ "Video: Huntsman says states, not the feds, should take the lead in responding to coronavirus outbreak". UtahPolicy.com. March 10, 2020.

- ^ "Perry, Huntsman Have Immigration Records Challenged During GOP Debate". NumbersUSA. September 13, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Guv, peers ask U.S. Senate to pass immigration reform". The Salt Lake Tribune. June 27, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman's Record Has Pros And Cons For Conservatives". The Huffington Post. May 28, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Gehrke, Robert (May 21, 2011). "Huntsman says border fence 'repulses' him, but may be necessary". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Pethokoukis, James (September 1, 2011). "My chat with Jon Huntsman about his economic plan". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Streitfeld, Rachel (August 5, 2011). "Huntsman woos New Hampshire moderates". CNN.

- ^ "Jon M Huntsman Jr named Chairman of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation" (Press release). Huntsman Cancer Institute. January 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ "Ford Names Jon Huntsman to Board of Directors" (Press release). Ford Motor Co. February 9, 2012. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Caterpillar Inc. (2012). Former Utah Governor and United States Ambassador to China Jon Huntsman to Join Caterpillar Board of Directors. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman Jr. Rejoins Chevron's Board of Directors" (Press release). Chevron Corporation. September 8, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Weddings: Mary Huntsman and Evan Morgan". The New York Times. October 18, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "The Road to Presidency 5". Sunshine State News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ Romney's great-great-grandfather, the early Mormon missionary Parley Pratt, is Huntsman's great-great-great-grandfather."Romney and Bush Are Cousins, Ancestry.com Finds - TIME.com". Time.

- ^ Berman, Craig (August 30, 2012). "Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart talk politics, conventions with Republican outcasts". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael (January 4, 2012). "On Stage, an Awkward Reminder of Personal Rifts in G.O.P." The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c "The Commonalities Between GOP Candidates Jon Huntsman and Mitt Romney -- New York Magazine". NYMag.com. July 29, 2011.

- ^ Oliphant, James (May 9, 2011). "Jon Huntsman was a keyboard wizard, but is a presidential run a rock 'n' roll fantasy?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Michele Roberts (May 16, 2008). "Gov. Huntsman's 30-year Passion". Heraldextra.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Embassy of the United States Beijing, China – Ambassador". August 11, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Governor Jon Huntsman Jr. to Give Snow College 2005 Commencement Address". Snow College. March 21, 2005. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Westminster Announces 2008 Commencement Speaker and Honorary Degree Recipients". Westminster College. 2008. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "U of U Commencement on May 7 to Graduate More than 7,000". University of Utah. April 26, 2010. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Jon M. Huntsman Jr., U.S. Ambassador to China, to Speak at Penn's 254th Commencement". University of Pennsylvania. February 22, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsman to N.H. grads: Don't sell America short". The Salt Lake Tribune. May 21, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Significant Sigs" Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Sigma Chi International Headquarters.

- ^ "Distinguished Eagle Scout Award" (PDF). Boy Scouts of America. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "Ambassador Huntsman diagnosed with skin cancer, sought treatment at Huntsman Cancer Institute". Salt Lake City Tribune. November 1, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ Jamie Ehrlich (June 10, 2020). "Jon Huntsman announces he has coronavirus". CNN.

- ^ Moreno, J. Edward (June 10, 2020). "Jon Huntsman tests positive for coronavirus". The Hill.

- ^ Roche, Lisa Riley (June 10, 2020). "Jon Huntsman Jr. tests positive for COVID-19". Deseret News.

- ^ "Jon Huntsman: The Potential Republican Presidential Candidate Democrats Most Fear". Time. May 12, 2011. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Burr, Thomas (May 9, 2011). "Is Huntsman distancing himself from LDS faith?". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Kirn, Walter (June 5, 2011). "Mormons Rock!". Newsweek.

- ^ George Stephanopoulos (May 20, 2011). "Transcript: Exclusive Interview With Jon Huntsman". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ Wong, Scott (August 21, 2011). "Huntsman: GOP can't become 'anti-science' party". Politico. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "2020 Regular Primary Canvass" (PDF). State of Utah.gov. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "2008 Canvass". June 11, 2009. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ "2004 Canvass" (PDF). June 12, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2008. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Huntsman Presidential Campaign Staff (archived)

- Biography at Ballotpedia

- Works by or about Jon Huntsman Jr. in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Financial information at OpenSecrets.org

- Official Biography at the United States Department of State (2017)

- "Jon Huntsman Could Do Without Bill Clinton's Kudos", Andrew Goldman, The New York Times Magazine, 4 January 2013

Jon Huntsman Jr.

View on GrokipediaEarly life and education

Family background and upbringing

Jon Huntsman Jr. was born on March 26, 1960.[13] He was the first of nine children born to Jon M. Huntsman Sr., a self-made chemical industry executive who founded Huntsman Corporation, and Karen Haight Huntsman.[14] Huntsman Sr. rose from impoverished origins in rural Idaho, where he was born in 1937 to a schoolteacher father and homemaker mother, to build a multinational enterprise through innovation in plastics and chemicals, amassing significant wealth that shaped the family's affluent circumstances.[15] [16] The Huntsman family adhered to the faith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with Karen Huntsman connected through her father, David B. Haight, a longtime apostle in the church hierarchy.[17] Jon Huntsman Jr. grew up primarily in Salt Lake City, Utah, amid this religious and entrepreneurial environment, where his father's business pursuits and emphasis on philanthropy—later exemplified by billions donated to cancer research and education—provided early exposure to public service and family-driven enterprise.[18] In 1970, when Huntsman Jr. was 10, the family briefly relocated eastward as his father joined the Nixon administration in a policy role before returning to Utah to expand the burgeoning company.[18] This peripatetic element underscored a childhood blending stability in Utah's Mormon community with the demands of his father's high-stakes career.Academic pursuits and early influences

Huntsman dropped out of high school during his senior year to pursue other interests, including music performance.[19][20] At age 19, he undertook a two-year mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Taiwan, where he acquired fluency in Mandarin Chinese and Taiwanese Hokkien, experiences that cultivated his lifelong interest in Asian affairs and international relations.[21] Following his mission, Huntsman attended the University of Utah before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania, from which he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in international politics in 1987.[5][22] His academic focus on international studies aligned with early exposures to global business through his father, Jon Huntsman Sr., a self-made chemical industry entrepreneur who founded Huntsman Corporation and instilled values of innovation, hard work, and philanthropy rooted in Mormon principles.[18] These formative years, marked by familial emphasis on self-reliance and service, alongside the linguistic and cultural immersion from his mission, profoundly shaped Huntsman's worldview, directing him toward public service and diplomacy rather than solely inheriting the family business.[23][24]Early career

Initial business involvements

Following his brief tenure as a White House staff assistant under President Ronald Reagan from 1982 to 1983, Jon Huntsman Jr. entered the private sector by joining the Huntsman Corporation, a multinational chemical manufacturing firm founded by his father, Jon Huntsman Sr., in 1970. He began in 1983 as a project manager and corporate secretary, roles that involved overseeing operational projects in the company's expanding petrochemical and packaging divisions.[25][19] From 1983 to 1989, Huntsman held various executive positions at the corporation, contributing to its growth during a period when the firm transitioned from niche packaging products, such as plastic egg cartons, to broader chemical production amid industry consolidation. These roles provided him with direct experience in international trade and manufacturing operations, leveraging the company's global supply chains.[25][19][26] After a return to government service in trade-related roles during the late 1980s and early 1990s, Huntsman rejoined the family business in 1993 as vice chairman of the board and a member of the executive committee, a position he maintained until 2001. In this capacity, he focused on strategic expansion and family governance of the enterprise, which by then had achieved multibillion-dollar revenues through acquisitions and diversification into specialty chemicals.[25][27]Entry into federal service

Huntsman entered federal service as a staff assistant in the White House under President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s.[9][28] In May 1989, President George H.W. Bush appointed him Deputy Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Trade Development, a role he held until 1990, followed by service as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Commerce for East Asian and Pacific Affairs until June 1992.[5][29] In these positions, Huntsman focused on trade policy and economic relations with Asia, leveraging his business background in international chemicals.[5] On August 11, 1992, Bush nominated Huntsman as U.S. Ambassador to Singapore, with Senate confirmation leading to presentation of credentials on September 22, 1992.[2] His tenure was brief, ending in early 1993 amid the presidential transition to Bill Clinton.[30] After returning to private sector roles, including leadership of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation from 1995 to 2001, Huntsman re-entered federal service in 2001 as Deputy U.S. Trade Representative under President George W. Bush, confirmed by unanimous Senate consent on August 6, 2001, and serving until 2003.[31][25] In this capacity, he negotiated free trade agreements across Asia and contributed to global trade initiatives.[21]Governorship of Utah

2004 election and first term

Jon Huntsman Jr. announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination for Governor of Utah on March 9, 2004, positioning himself as a business-oriented reformer drawing on his experience as United States Deputy Trade Representative.[32] In the Republican primary held on June 22, 2004, Huntsman secured the nomination by defeating incumbent Governor Olene Walker and State Senator Nolan Karras, capitalizing on voter desire for change despite Walker's appointment to the office following Michael Leavitt's resignation.[33] His campaign emphasized economic growth, education improvement, and fiscal responsibility, contrasting with Democratic nominee Scott Matheson Jr., the son of former Governor Scott M. Matheson, in debates that highlighted differences on taxation and government efficiency.[34] In the general election on November 2, 2004, Huntsman and running mate Gary Herbert won decisively with 531,190 votes, or 57.74% of the popular vote, against Matheson's 368,859 votes (40.12%), reflecting strong Republican support in the heavily conservative state.[35] [36] Huntsman was inaugurated as Utah's 16th governor on January 3, 2005, pledging to streamline government operations and foster business development.[4] During his first term from 2005 to 2009, Huntsman prioritized tax reforms, signing legislation in 2007 that simplified the income tax code, reduced rates, and eliminated certain deductions to promote economic competitiveness, which contributed to Utah's ranking among the top states for business climate.[37] [38] The administration oversaw budget surpluses, including a $1.6 billion surplus in fiscal year 2007, enabling investments in infrastructure and a tripling of the state's rainy day fund to historic levels exceeding $400 million by 2008, bolstering fiscal resilience amid national economic pressures.[39] [40] Economic policies supported job growth, with Utah achieving unemployment rates below the national average and leading in private-sector job creation during parts of the term.[41] Education initiatives increased funding for K-12 and higher education, while health care efforts focused on expanding access through market-based reforms rather than mandates.[4] Huntsman's approval ratings remained high, often above 70%, reflecting public approval of the state's prosperity under his leadership.[42]Policy achievements and economic record

During Jon Huntsman Jr.'s tenure as Governor of Utah from 2005 to 2009, the state achieved the highest job growth rate among all U.S. states, averaging 3.4% annually from 2005 to 2008.[43] This performance contributed to historic lows in unemployment and positioned Utah as a leader in economic expansion amid national challenges.[28] Huntsman maintained balanced budgets, preserved the state's triple-A bond rating, and tripled the rainy-day fund from approximately $250 million to over $750 million, enhancing fiscal resilience.[44] A cornerstone of Huntsman's economic policy was comprehensive tax reform enacted in 2007, which lowered individual income tax rates from a top marginal rate of 7% to a flat 5%, eliminated taxes on groceries and certain services, and shifted the tax burden toward a more business-friendly structure.[45] This overhaul, praised by the Cato Institute as a model for simplifying tax codes while broadening the base, represented the largest tax cut in Utah history, reducing the overall tax burden and stimulating investment.[46] The reforms coincided with budget surpluses that enabled targeted investments without increasing state debt. Huntsman prioritized education funding, proposing and signing budgets that increased K-12 allocations by significant margins, including a proposed $2.5 billion for the Minimum School Program in 2005, directing 84% of new general fund revenues to education.[47] His administration also launched the Utah Science Technology and Research (USTAR) initiative in 2006, investing over $60 million initially to recruit top researchers and develop innovation centers at universities, fostering high-tech clusters in fields like biotechnology and nanotechnology to drive long-term economic diversification.[48] In energy policy, Huntsman advanced clean energy development, signing legislation to promote nuclear power as a reliable baseload source and supporting wind energy projects, while joining the Western Regional Climate Action Initiative to explore greenhouse gas reductions without imposing burdensome mandates.[49] These efforts balanced environmental goals with economic imperatives, contributing to Utah's reputation for pragmatic governance and sustained growth.[4]Re-election and second term

Huntsman won re-election on November 4, 2008, defeating Democratic nominee Bob Springmeyer and his running mate Josie Valdez with 77.63% of the vote (734,049 votes) to their 19.72% (186,503 votes), alongside minor candidates accounting for the remainder.[50] This result marked the largest percentage victory in a competitive Utah gubernatorial election, reflecting Huntsman's sustained popularity amid strong economic performance during his first term.[5] Inaugurated for a second term on January 5, 2009, Huntsman focused on mitigating the effects of the ongoing national recession, including acceptance of portions of the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus package while emphasizing state-level fiscal discipline and infrastructure investments.[51] His administration prioritized job retention in key sectors like energy and technology, building on prior tax reductions and regulatory reforms that had contributed to Utah's above-average growth rates.[4] Huntsman's second term lasted only seven months, concluding with his resignation on August 11, 2009, to accept President Barack Obama's nomination as U.S. Ambassador to China—a bipartisan appointment confirmed unanimously by the Senate on August 4.[52] Lieutenant Governor Gary Herbert succeeded him, maintaining continuity in economic and education policies. Huntsman's early departure underscored his diplomatic expertise, honed from prior roles, over prolonged state leadership.[5]Diplomatic roles

Ambassador to China

President Barack Obama nominated Jon Huntsman Jr. as United States Ambassador to China on May 16, 2009, citing his Mandarin fluency, prior diplomatic experience as ambassador to Singapore from 1992 to 1993, and extensive business ties in Asia through the Huntsman Corporation.[53] The Senate confirmed the nomination unanimously on August 7, 2009, reflecting bipartisan support for his qualifications despite his Republican affiliation.[54] Huntsman was sworn in on August 11, 2009, presented credentials on August 28, 2009, and served until departing the post on April 28, 2011.[2] During his tenure, Huntsman prioritized advancing bilateral cooperation on global challenges, including climate change, clean energy, and economic recovery following the 2008 financial crisis. He facilitated high-level dialogues, such as those marking the 30th anniversary of U.S.-China diplomatic relations in 2009, and promoted people-to-people exchanges alongside military and economic ties.[55][56] Huntsman's approach emphasized mutual interests in non-proliferation and trade, leveraging his personal connections to Chinese leaders to stabilize relations amid tensions over issues like currency valuation and intellectual property.[57] Huntsman's term included notable public incidents that highlighted frictions. On February 20, 2011, he appeared briefly at an anti-government protest in Beijing's Wangfujing district amid calls for a "Jasmine Revolution," prompting Chinese state media to accuse him of inciting unrest; Huntsman stated his presence was coincidental while walking nearby.[58][59] In his April 2011 farewell address, he criticized the detention of Chinese dissidents and activists, asserting that true stability required addressing human rights concerns.[60] Huntsman resigned in early 2011 to return to the United States, officially citing a desire to reconnect with family, though the move fueled speculation about his impending 2012 Republican presidential campaign.[61] His service was praised for enhancing U.S. leverage in bilateral talks through pragmatic engagement, though some analysts noted limited progress on core disputes like trade imbalances.[62]Ambassador to Russia

President Donald Trump announced on July 19, 2017, his intention to nominate Jon Huntsman Jr. as the United States Ambassador to Russia.[63] The Senate confirmed the nomination unanimously on September 28, 2017.[64] Huntsman presented his credentials to Russian authorities on October 2, 2017, formally assuming the role amid heightened tensions following Russia's interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[2] During his confirmation hearings, Huntsman acknowledged Russia's meddling in the election as a fact, stating there was "no question" Moscow had interfered, while emphasizing the need for diplomatic engagement to manage bilateral risks.[65] His tenure occurred against a backdrop of deteriorating relations, including U.S. sanctions in response to the 2018 nerve agent poisoning of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom, which prompted the expulsion of 60 Russian diplomats from the U.S. and reciprocal actions by Russia that reduced U.S. embassy staffing in Moscow by about 50%. Huntsman focused on maintaining embassy operations and fostering limited people-to-people contacts, such as educational and cultural exchanges, despite restrictions imposed by Russian authorities.[66] Huntsman maintained a relatively low public profile in Moscow, prioritizing behind-the-scenes diplomacy over high-visibility confrontations, even as issues like the U.S. withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019 and ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Syria strained ties.[66] In a May 2019 interview, he argued that the U.S.-Russia estrangement "has gone on too long," advocating for pragmatic dialogue to address mutual security concerns rather than isolation.[67] This approach reflected his foreign policy realism, balancing accountability for Russian actions with the recognition that complete disengagement risked escalation without advancing U.S. interests. On August 6, 2019, Huntsman submitted his resignation to President Trump, effective October 3, 2019, citing a desire to return to Utah and fulfill broader civic obligations as an American citizen.[66] In his letter, he described the posting as occurring during a "historically difficult time" and urged continued pressure on Russia to cease behaviors threatening U.S. allies and interests.[68] Following his departure, Huntsman critiqued an over-reliance on sanctions, suggesting the U.S. incorporate more incentives to influence Russian conduct effectively.[69] His service ended without major diplomatic breakthroughs but preserved channels for communication amid adversarial dynamics.[2]Presidential and gubernatorial campaigns

2012 Republican presidential bid

Jon Huntsman Jr. formally announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination on June 21, 2011, at Liberty State Park in Jersey City, New Jersey, shortly after resigning as U.S. Ambassador to China.[70] He positioned himself as a results-oriented conservative with a record of bipartisan governance in Utah and international experience, emphasizing economic recovery through job creation and criticizing President Barack Obama's policies while acknowledging Obama's personal decency.[70] Huntsman's campaign strategy centered on the New Hampshire primary, where he invested heavily in retail politics and appealed to independent voters, largely bypassing the Iowa caucuses to conserve resources.[71] In the Iowa caucuses on January 3, 2012, Huntsman garnered less than 1% of the vote, finishing far behind frontrunners due to his minimal presence in the state.[72] He intensified attacks on Mitt Romney in New Hampshire, questioning Romney's business record and electability, though these drew some backlash within the party for elevating Romney as the primary alternative to other conservatives.[73][74] On January 10, 2012, Huntsman achieved third place in the New Hampshire primary with 17% of the vote, behind Romney's 39% and Ron Paul's 23%, a result that provided a modest boost but failed to generate the momentum needed against the more conservative field.[75] Facing dismal national polling and an inability to expand beyond New Hampshire, Huntsman suspended his campaign on January 16, 2012, in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and endorsed Romney as the nominee best positioned to defeat Obama.[76][77] The early exit reflected challenges in connecting with the Republican base's preference for ideological purity over Huntsman's pragmatic, moderate conservatism, despite his fundraising success and organizational efforts.[76]2020 Utah gubernatorial effort

Following his resignation as U.S. Ambassador to Russia on August 6, 2019, Jon Huntsman Jr. returned to Utah and considered a third term as governor amid incumbent Gary Herbert's announcement that he would not seek re-election.[68][78] On November 14, 2019, Huntsman formally announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination, emphasizing Utah's rapid population growth as the paramount challenge requiring experienced leadership to manage infrastructure, housing, and economic pressures without excessive taxation or regulation.[79][80] He positioned himself as a pragmatic conservative with a proven record of bipartisan governance, drawing on his prior terms as governor from 2005 to 2009, during which Utah achieved strong economic growth and budget surpluses.[81] Huntsman's campaign gained early momentum, bolstered by his name recognition and fundraising prowess; he raised over $4 million by early 2020, outpacing initial rivals.[82] On February 7, 2020, he selected Provo Mayor Michelle Kaufusi as his running mate for lieutenant governor, highlighting her executive experience in a growing city and appealing to Utah's diverse suburban voters.[83] However, the race intensified against Lieutenant Governor Spencer Cox, who secured endorsements from Herbert and positioned himself as a "compassionate conservative" focused on unity amid national polarization.[84] Huntsman's campaign faced headwinds, including his contraction of COVID-19 in June 2020, which forced quarantine and limited in-person outreach just before the primary.[85] The Republican primary occurred on June 30, 2020, via mail-in voting due to the pandemic. Cox emerged victorious with 367,172 votes (53.0 percent) to Huntsman's 325,236 (47.0 percent), a margin of fewer than 42,000 votes.[86][87] Huntsman conceded on July 6, 2020, acknowledging the results after absentee and provisional ballots confirmed Cox's lead, and praised the democratic process while expressing disappointment at the outcome.[88] Analysts attributed Cox's upset to stronger grassroots organization, Herbert's backing, and voter preference for a fresh face less associated with national GOP infighting, despite Huntsman's initial polling advantages.[89] In the primary's aftermath, some supporters urged Huntsman to pursue a write-in campaign in the general election, citing Utah's Republican dominance and potential for an independent bid.[90] Huntsman declined, announcing on July 13, 2020, that he would not run as a write-in candidate, reiterating support for Republican unity against Democratic nominee Chris Peterson.[91] He reaffirmed this on August 28, 2020, effectively ending his 2020 effort and allowing Cox to proceed unencumbered to the general election victory.[92]Post-2020 activities

Business leadership and board roles

In September 2020, Huntsman rejoined the board of directors of Chevron Corporation, where he had previously served from 2014 to 2017.[93] In October 2020, he was re-elected to the board of Ford Motor Company, resuming a role held from 2012 to 2017 prior to his ambassadorship to Russia.[9] Huntsman continued his service on the board of Huntsman Corporation, the chemical manufacturer founded by his father, having been appointed as a director on February 1, 2012.[94] At Ford, Huntsman's responsibilities expanded in April 2021 to vice chair of policy, advising CEO Jim Farley and Executive Chair Bill Ford on strategic policy issues amid the company's transition to electric vehicles and autonomous driving technologies.[95] In this capacity, he contributed to board oversight of global operations and regulatory compliance.[96] In March 2024, Mastercard named Huntsman vice chairman and president of strategic growth, effective April 15, 2024, tasking him with leading efforts to forge public-private partnerships and expand commercial collaborations in emerging markets.[97] This executive role leverages his diplomatic experience to advance Mastercard's growth in payment technologies and inclusive finance initiatives.[10]Political engagements and commentary

Following his withdrawal from the 2020 Utah gubernatorial race after losing the Republican primary to Spencer Cox on July 7, 2020, Huntsman refrained from mounting a write-in campaign, announcing on August 28, 2020, that he would not pursue further electoral efforts that year.[98] In the wake of the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot, Huntsman publicly criticized former President Donald Trump, stating on January 7, 2021, that Trump had prioritized "self interest above the nation's" in refusing to concede the 2020 election, which Huntsman described as a failure of leadership that undermined democratic institutions.[11] Huntsman engaged with centrist political initiatives through No Labels, a bipartisan group advocating for third-party alternatives to the major parties. On July 17, 2023, he appeared alongside Senator Joe Manchin at a No Labels town hall, expressing openness to supporting an independent presidential ticket as a means to foster compromise but clarifying he was not seeking a vice-presidential role.[99] Speculation arose in July 2023 about his potential candidacy on the No Labels ticket, given his diplomatic experience and moderate Republican profile, though he denied presidential ambitions on November 14, 2023, amid the group's challenges in securing a viable nominee.[100][101] No Labels ultimately opted against fielding a 2024 presidential ticket on April 4, 2024, citing difficulties in attracting high-profile candidates amid partisan opposition.[102] In October 2022, Huntsman endorsed incumbent Utah Senator Mike Lee for re-election, praising Lee's focus on fiscal restraint and constitutional principles despite Lee's alignment with Trump-era policies.[103] He also took a stand on university governance, halting donations to the University of Pennsylvania on October 16, 2023, in response to the institution's perceived inadequate handling of antisemitism following the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel, reflecting concerns over institutional responses to geopolitical tensions.[104] By March 2025, Huntsman continued offering pointed commentary on Republican leadership, warning in public discussions that Trump's approach risked midterm defeats without a shift toward effective governance and critiquing associated disruptions in global trade dynamics.[105][106] These statements underscored his ongoing emphasis on pragmatic, experience-based politics over ideological extremes.Political positions

Fiscal conservatism and economic policy