Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mormons

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| +17,255,394[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States | 6,868,793[2] |

| Mexico | 1,516,406[3] |

| Brazil | 1,494,571[4] |

| Philippines | 867,271[5] |

| Peru | 637,180[6] |

| Chile | 607,583[7] |

| Argentina | 481,518[8] |

| Guatemala | 290,068[9] |

| Religions | |

| Mormonism | |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the Second Great Awakening. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several groups following different leaders; the majority followed Brigham Young, while smaller groups followed Sidney Rigdon and James Strang. Many who did not follow Young eventually merged into the Community of Christ, led by Smith’s son, Joseph Smith III. The term Mormon typically refers to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the largest branch, which followed Brigham Young. People who identify as Mormons may also be independently religious, secular, and non-practicing or belong to other denominations.

Since 2018, the LDS Church has expressed the desire that its followers be referred to as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or just members, if the identity of the church is made clear previously in the context, as the term Mormon can be considered offensive by the community.[a][14]

Members have developed a strong sense of community that stems from their doctrine and history. One of the central doctrinal issues that defined Mormonism in the 19th century was the practice of plural marriage, a form of religious polygamy. From 1852 until 1904, when the LDS Church banned the practice, many members who had followed Brigham Young to the Utah Territory openly practiced polygamy. Members dedicate significant time and resources to serving in their churches. A prominent practice among young and retired members of the LDS Church is to serve a full-time proselytizing mission. Members have a health code that eschews alcoholic beverages, tobacco, tea, coffee, and addictive substances. They tend to be very family-oriented and have strong connections across generations and with extended family, reflecting their belief that families can be sealed together beyond death. Members also adhere to a law of chastity, requiring abstention from sexual relations outside heterosexual marriage and fidelity within marriage.

Mormons identify as Christian,[15] but some non-Mormons consider church members to be non-Christian[16][17] because some of their beliefs differ from those of Nicene Christianity. They believe that Christ's church was restored through Joseph Smith and is guided by living prophets and apostles. Members believe in the Bible and other books of scripture, such as the Book of Mormon. They have a unique view of cosmology and believe that all people are literal spirit children of God: they believe that returning to God requires following the example of Jesus Christ and accepting his atonement through repentance and ordinances such as baptism.

During the 19th century, converts into LDS Church tended to gather in a central geographic location, a trend that reversed somewhat in the 1920s and 1930s. The center of LDS Church cultural influence is in Utah, and North America has more members than any other continent, although about 60% of LDS Church members live outside the United States. As of December 31, 2021, the LDS Church reported a membership of 16,805,400.[18]

Terminology

[edit]The terminology preferred by the church itself has varied over time. At various points, the church has embraced the term Mormon and stated that other sects within the shared faith tradition should not be called Mormon.[19]

The word Mormon was initially coined to describe any person who considers the Book of Mormon to be a scripture volume. Mormonite and Mormon were originally descriptive terms used both by outsiders to the faith, church members, and occasionally church leaders.[20][better source needed] The term Mormon later was sometimes used derogatorily; such use may have developed during the 1838 Mormon War,[21] although church members and leaders "embraced the term", according to church historian Matthew Bowman, and by the end of the 1800s it was broadly used.[22]

The LDS Church has made efforts, including in 1982, in 2001 prior to the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, in 2011 after The Book of Mormon appeared on Broadway, and again in 2018, to encourage the use of the church's full name, rather than the terms Mormon or LDS.[14] According to Patrick Mason, chair of Mormon studies at Claremont Graduate University and Richard Bennett, a professor of church history at Brigham Young University, this is because non-church members have historically been confused about whether it represents a Christian faith, which concerns church leaders, who want to emphasize that the church is a Christian church.[14][22] The term Mormon also causes concern for church leaders because it has been used to include splinter groups such as Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints, who practice polygamy, which the LDS Church does not; Mason said "For more than 100 years, the mainstream LDS Church has gone to great pains to distance itself from those who practice polygamy. It doesn't want to have any confusion there between those two groups."[14]

In 2018, the LDS Church published a style guide that encourages the use of the terms "the Church", the "Church of Jesus Christ" or the "restored Church of Jesus Christ" as shortened versions after an initial use of the full name.[23][22][24] According to church historian Bowman, 'the term "restored" refers to the idea that the original Christian religion is obsolete, and Mormons alone are practicing true Christianity.'[22]

The 2018 style guide rejects the term Mormons along with "Mormon Church", "Mormonism", and the abbreviation LDS.[22] The second-largest sect, the Community of Christ, also rejects the term Mormon due to its association with the practice of polygamy among Brighamite sects.[25] Other sects, including several fundamentalist branches of the Brighamite tradition, embrace the term Mormon.

History

[edit]The history of the Mormons has shaped them into a people with a strong sense of unity and commonality.[26] From the start, Mormons have tried to establish what they call "Zion", a utopian society of the righteous.[27] Mormon history can be divided into three broad periods: (1) the early history during the lifetime of Joseph Smith, (2) a "pioneer era" under the leadership of Brigham Young and his successors, and (3) a modern era beginning around the turn of the 20th century. In the first period, Smith attempted to build a city called Zion, where converts could gather. Zion became a "landscape of villages" in Utah during the pioneer era. In modern times, Zion is still an ideal, though Mormons gather together in their individual congregations rather than in a central geographic location.[28]

Beginnings

[edit]

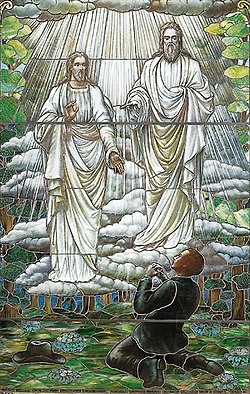

The Mormon movement began with the publishing of the Book of Mormon in March 1830, which Smith stated was a translation of golden plates containing the religious history of an ancient American civilization that the ancient prophet-historian Mormon had compiled. Smith stated that an angel had directed him to the golden plates buried in the Hill Cumorah.[29] On April 6, 1830, Smith founded the Church of Christ.[30] In 1832, Smith added an account of a vision he had sometime in the early 1820s while living in Upstate New York.[31] Some Mormons regarded this vision as the most important event in human history after the birth, ministry, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.[32]

The early church grew westward as Smith sent missionaries to proselytize.[33] In 1831, the church moved to Kirtland, Ohio, where missionaries had made a large number of converts[34] and Smith began establishing an outpost in Jackson County, Missouri,[35] where he planned to eventually build the city of Zion (or the New Jerusalem).[36] In 1833, Missouri settlers, alarmed by the rapid influx of Mormons, expelled them from Jackson County into the nearby Clay County, where local residents were more welcoming.[37] After Smith led a mission, known as Zion's Camp, to recover the land,[38] he began building Kirtland Temple in Lake County, Ohio, where the church flourished.[39] When the Missouri Mormons were later asked to leave Clay County in 1836, they secured land in what would become Caldwell County.[40]

The Kirtland era ended in 1838 after the failure of a church-sponsored anti-bank caused widespread defections,[41] and Smith regrouped with the remaining church in Far West, Missouri.[42] During the fall of 1838, tensions escalated into the Mormon War with the old Missouri settlers.[43] On October 27, the governor of Missouri ordered that the Mormons "must be treated as enemies" and be exterminated or driven from the state.[44] Between November and April, some eight thousand displaced Mormons migrated east into Illinois.[45]

In 1839, the Mormons purchased the small town of Commerce, converted swampland on the banks of the Mississippi River, renamed the area Nauvoo, Illinois,[46] and began constructing the Nauvoo Temple. The city became the church's new headquarters and gathering place, and it grew rapidly, fueled in part by converts immigrating from Europe.[47] Meanwhile, Smith introduced temple ceremonies meant to seal families together for eternity, as well as the doctrines of eternal progression or exaltation[48] and plural marriage.[49] Smith created a service organization for women called the Relief Society and the Council of Fifty, representing a future theodemocratic "Kingdom of God" on the earth.[50] Smith also published the story of his First Vision, in which the Father and the Son appeared to him when he was about 14 years old.[51] This vision would come to be regarded by some Mormons as the most important event in human history after the birth, ministry, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.[32]

In 1844, local prejudices and political tensions, fueled by Mormon peculiarity, internal dissent, and reports of polygamy, escalated into conflicts between Mormons and "anti-Mormons" in Illinois and Missouri.[52] Smith was arrested, and on June 27, 1844, he and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois.[53] Because Hyrum was Smith's logical successor,[54] their deaths caused a succession crisis,[55] and Brigham Young assumed leadership over most Latter Day Saints.[56] Young had been a close associate of Smith's and was the senior apostle of the Quorum of the Twelve.[57] Smaller groups of Latter-Day Saints followed other leaders to form other denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement.[58]

Pioneer era

[edit]

For two years after Joseph Smith's death, conflicts escalated between Mormons and other Illinois residents. To prevent war, Brigham Young led the Mormon pioneers (constituting most of the Latter Day Saints) to a temporary winter quarters in Nebraska and then, eventually (beginning in 1847), to what became the Utah Territory.[59] Having failed to build Zion within the confines of American society, the Mormons began to construct a society in isolation based on their beliefs and values.[60] The cooperative ethic that Mormons had developed over the last decade and a half became important as settlers branched out and colonized a large desert region now known as the Mormon Corridor.[61] Colonizing efforts were seen as religious duties, and the new villages were governed by the Mormon bishops (local lay religious leaders).[62] The Mormons viewed land as a commonwealth, devising and maintaining a cooperative system of irrigation that allowed them to build a farming community in the desert.[63]

From 1849 to 1852, the Mormons greatly expanded their missionary efforts, establishing several missions in Europe, Latin America, and the South Pacific.[64] Converts were expected to "gather" to Zion, and during Young's presidency (1847–77), over seventy thousand Mormon converts immigrated to America.[64] Many of the converts came from England and Scandinavia and were quickly assimilated into the Mormon community.[65] Many of these immigrants crossed the Great Plains in wagons drawn by oxen, while some later groups pulled their possessions in small handcarts. During the 1860s, newcomers began using the new railroad that was under construction.[66]

In 1852, church leaders publicized the previously secret practice of plural marriage, a form of polygamy.[67] Over the next 50 years, many Mormons (between 20 and 30 percent of Mormon families)[68] entered into plural marriages as a religious duty, with the number of plural marriages reaching a peak around 1860 and then declining through the rest of the century.[69] Besides the doctrinal reasons for plural marriage, the practice made some economic sense, as many of the plural wives were single women who arrived in Utah without brothers or fathers to offer them societal support.[70]

By 1857, tensions had again escalated between Mormons and other Americans, primarily due to accusations involving polygamy and the theocratic rule of the Utah Territory by Brigham Young.[71] In 1857, U.S. President James Buchanan sent an army to Utah, which Mormons interpreted as open aggression against them. Fearing a repeat of Missouri and Illinois, the Mormons prepared to defend themselves, determined to torch their own homes if they were invaded.[72] The Utah War ensued from 1857 to 1858, in which the most notable instance of violence was the Mountain Meadows massacre when leaders of a local Mormon militia ordered the killing of a civilian emigrant party that was traveling through Utah during the escalating tensions.[73] In 1858, Young agreed to step down from his position as governor and was replaced by a non-Mormon, Alfred Cumming.[74] Nevertheless, the LDS Church still wielded significant political power in the Utah Territory.[75]

At Young's death in 1877, he was followed by other LDS Church presidents, who resisted efforts by the United States Congress to outlaw Mormon polygamous marriages.[76] In 1878, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. United States that religious duty was not a suitable defense for practicing polygamy. Many Mormon polygamists went into hiding; later, Congress began seizing church assets.[76] In September 1890, church president Wilford Woodruff issued a Manifesto that officially suspended the practice of polygamy.[77] Although this Manifesto did not dissolve existing plural marriages, relations with the United States markedly improved after 1890, such that Utah was admitted as a U.S. state in 1896. After the Manifesto, some Mormons continued to enter into polygamous marriages, but these eventually stopped in 1904 when church president Joseph F. Smith disavowed polygamy before Congress and issued a "Second Manifesto" calling for all plural marriages in the church to cease. Eventually, the church adopted a policy of excommunicating members found practicing polygamy, and today actively seeks to distance itself from "fundamentalist" groups that continue the practice.[78]

Modern times

[edit]During the early 20th century, Mormons began reintegrating into the American mainstream. In 1929, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir began broadcasting a weekly performance on national radio, becoming an asset for public relations.[79] Mormons emphasized patriotism and industry, rising in socioeconomic status from the bottom among American religious denominations to the middle class.[80] In the 1920s and 1930s, Mormons began migrating out of Utah, a trend hurried by the Great Depression, as Mormons looked for work wherever they could find it.[81] As Mormons spread out, church leaders created programs to help preserve the tight-knit community feel of Mormon culture.[82] In addition to weekly worship services, Mormons began participating in numerous programs such as Boy Scouting, a Young Women organization, church-sponsored dances, ward basketball, camping trips, plays, and religious education programs for youth and college students.[83] During the Great Depression, the church started a welfare program to meet the needs of poor members, which has since grown to include a humanitarian branch that provides relief to disaster victims.[84]

During the later half of the 20th century, there was a retrenchment movement in Mormonism in which Mormons became more conservative, attempting to regain their status as a "peculiar people".[85] Though the 1960s and 1970s brought changes such as Women's Liberation and the civil rights movement, Mormon leaders were alarmed by the erosion of traditional values, the sexual revolution, the widespread use of recreational drugs, moral relativism, and other forces they saw as damaging to the family.[86] Partly to counter this, Mormons put an even greater emphasis on family life, religious education, and missionary work, becoming more conservative in the process. As a result, Mormons today are probably less integrated with mainstream society than they were in the early 1960s.[87]

Although black people have been members of Mormon congregations since Joseph Smith's time, before 1978, black membership was small. From 1852 to 1978, the LDS Church enforced a policy restricting men of black African descent from being ordained to the church's lay priesthood.[88] The church was sharply criticized for its policy during the civil rights movement, but the policy remained in force until a 1978 reversal that was prompted in part by questions about mixed-race converts in Brazil.[89] In general, Mormons greeted the change with joy and relief.[89] Since 1978, black membership has grown, and in 1997 there were approximately 500,000 black church members (about 5 percent of the total membership), mostly in Africa, Brazil, and the Caribbean.[90] Black membership has continued to grow substantially, especially in West Africa, where two temples have been built.[91] Some black Mormons are members of the Genesis Group, an organization of black members that predates the priesthood ban and is endorsed by the church.[92]

The LDS Church grew rapidly after World War II and became a worldwide organization as missionaries were sent across the globe. The church doubled in size every 15 to 20 years,[93] and by 1996, there were more Mormons outside the United States than inside.[94] In 2012, there were an estimated 14.8 million Mormons,[95] with roughly 57 percent living outside the United States.[96] It is estimated that approximately 4.5 million Mormons – approximately 30% of the total membership – regularly attend services.[97] A majority of U.S. Mormons are white and non-Hispanic (84 percent).[98] Most Mormons are distributed in North and South America, the South Pacific, and Western Europe. The global distribution of Mormons resembles a contact diffusion model, radiating out from the organization's headquarters in Utah.[99] The church enforces general doctrinal uniformity, congregations on all continents teach the same doctrines, and international Mormons tend to absorb a good deal of Mormon culture, possibly because of the church's top-down hierarchy and missionary presence. However, international Mormons often bring pieces of their own heritage into the church, adapting church practices to local cultures.[100]

As of December 2019, the LDS Church reported having 16,565,036 members worldwide.[101] Chile, Uruguay, and several areas in the South Pacific have a higher percentage of Mormons than the United States (which is at about 2 percent).[102] South Pacific countries and dependencies that are more than 10 percent Mormon include American Samoa, the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Niue, Samoa, and Tonga.

Culture and practices

[edit]Isolation in Utah had allowed Mormons to create a culture of their own.[103] As the faith spread worldwide, many of its more distinctive practices followed. Mormon converts are urged to undergo lifestyle changes, repent of sins, and adopt sometimes atypical standards of conduct.[103] Practices common to Mormons include studying scriptures, praying daily, fasting regularly, attending Sunday worship services, participating in church programs and activities on weekdays, and refraining from work on Sundays when possible. The most important part of the church services is considered to be the Lord's Supper (commonly called sacrament), in which church members renew covenants made at baptism.[104] Mormons also emphasize standards they believe were taught by Jesus Christ, including personal honesty, integrity, obedience to the law, chastity outside marriage, and fidelity within marriage.[105]

In 2010, around 13–14 percent of Mormons lived in Utah, the center of cultural influence for Mormonism.[106] Utah Mormons (as well as Mormons living in the Intermountain West) are on average more culturally and politically conservative than those living in some cosmopolitan centers elsewhere in the U.S.[107] Utahns self-identifying as Mormon also attend church somewhat more on average than Mormons living in other states. (Nonetheless, whether they live in Utah or elsewhere in the U.S., Mormons tend to be more culturally and politically conservative than members of other U.S. religious groups.)[108] Utah Mormons often emphasize pioneer heritage more than international Mormons, who generally are not descendants of the Mormon pioneers.[100]

Mormons have a strong sense of communality that stems from their doctrine and history.[109] LDS Church members have a responsibility to dedicate their time and talents to helping the poor and building the church. The church is divided by locality into congregations called "wards", with several wards or branches to create a "stake".[110] Most church leadership positions are lay positions, and church leaders may work 10 to 15 hours a week in unpaid church service.[111] Observant Mormons also contribute 10 percent of their income to the church as tithing.[112] Paying tithing is one of the prerequisites for entrance into Mormon temples. Many LDS young men, women, and elderly couples choose to serve a proselytizing mission, during which they dedicate all of their time to the church without pay.[113] Members are often involved in humanitarian efforts.

Mormons adhere to the Word of Wisdom, a health law or code that is interpreted as prohibiting the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, coffee and tea,[114] while encouraging the use of herbs, grains, fruits, and a moderate consumption of meat.[115] The Word of Wisdom is also understood to forbid other harmful and addictive substances and practices, such as the use of illegal drugs and abuse of prescription drugs.[116] Mormons are encouraged to keep a year's supplies, including food and financial reserves.[117] Mormons also oppose behaviors such as viewing pornography and gambling.[105]

The concept of a united family that lives and progresses forever is at the core of Latter-day Saint doctrine, and Mormons place a high importance on family life.[118] Many Mormons hold weekly Family Home Evenings, in which an evening is set aside for family bonding, study, prayer, and other activities they consider to be wholesome. Latter-day Saint fathers who hold the priesthood typically name and bless their children shortly after birth to formally give the child a name. Mormon parents hope and pray that their children will gain testimonies of the "gospel"[vague] so they can grow up and marry in temples.[119]

Mormons are encouraged to adhere to the law of chastity, requiring abstention from sexual relations outside opposite-sex marriage and strict fidelity within marriage. All sexual activity (heterosexual and homosexual) outside marriage is considered a grave sin, with marriage recognized as only between a man and a woman.[120] Same-sex marriages are not performed or supported by the LDS Church. Church members are encouraged to marry and have children, and Latter-day Saint families tend to be larger than average. Mormons are opposed to abortion, except in some exceptional circumstances, such as when pregnancy is the result of incest or rape or when the life or health of the mother is in serious jeopardy.[121] Many practicing adult Mormons wear religious undergarments that remind them of covenants and encourage them to dress modestly. Latter-day Saints are counseled not to partake in any form of media that is obscene or pornographic in any way, including media that depicts graphic representations of sex or violence. Tattoos and body piercings are generally discouraged.[122]

LGBTQ Mormons remain in good standing in the church if they abstain from homosexual relations and obey the law of chastity.[123] While there are no official numbers, LDS Family Services estimates that, on average, four or five members per LDS ward experience same-sex attraction.[124] Gary Watts, former president of Family Fellowship, estimates that only 10 percent of homosexuals stay in the church.[125] Many of these individuals have come forward through different support groups or websites discussing their homosexual attractions and concurrent church membership.[126][127][128]

Groups within Mormonism

[edit]Note that the categories below are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Latter-day Saints ("LDS")

[edit]

Members of the LDS Church, also known as Latter-day Saints, constitute over 95 percent of Mormons.[129] The beliefs and practices of LDS Mormons are generally guided by the teachings of LDS Church leaders. However, several smaller groups substantially differ from "mainstream" Mormonism in various ways.

LDS Church members who do not actively participate in worship services or church callings are often called "less-active" or "inactive" (akin to the qualifying expressions non-observant or non-practicing used in relation to members of other religious groups).[130] The LDS Church does not release statistics on church activity, but it is likely that about 40 percent of Mormons in the United States and 30 percent worldwide regularly attend worship services.[131] Reasons for inactivity can include rejection of the fundamental beliefs, history of the church, lifestyle incongruities with doctrinal teachings or problems with social integration.[132] Activity rates tend to vary with age, and disengagement occurs most frequently between age 16 and 25. In 1998, the church reported that most less active members returned to church activity later in life.[133] As of 2017, the LDS Church was losing millennial-age members,[134] a phenomenon not unique to the LDS Church.[135] Former Latter-day Saints who seek to disassociate themselves from the religion are often referred to as ex-Mormons.

Fundamentalist Mormons

[edit]Members of sects that broke with the LDS Church over the issue of polygamy have become known as fundamentalist Mormons; these groups differ from mainstream Mormonism primarily in their belief in and practice of plural marriage. There are thought to be between 20,000 and 60,000 members of fundamentalist sects (0.1–0.4 percent of Mormons), with roughly half of them practicing polygamy.[136] There are many fundamentalist sects, the largest two being the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church) and the Apostolic United Brethren (AUB). In addition to plural marriage, some of these groups also practice a form of Christian communalism known as the law of consecration or the United Order. The LDS Church seeks to distance itself from all such polygamous groups, excommunicating their members if discovered practicing or teaching it,[137] and today, a majority of Mormon fundamentalists have never been members of the LDS Church.[138]

Liberal Mormons

[edit]

Liberal Mormons, also known as Progressive Mormons, take an interpretive approach to LDS teachings and scripture.[130] They look to the scriptures for spiritual guidance, but may not necessarily believe the teachings to be literally or uniquely true. For liberal Mormons, revelation is a process through which God gradually brings fallible human beings to greater understanding.[139] A person in this group is sometimes mistakenly regarded by others within the mainstream church as a Jack Mormon, although this term is more commonly used to describe a different group with distinct motives to live the gospel in a non-traditional manner.[140] Liberal Mormons place doing good and loving fellow human beings above the importance of believing correctly.[141] In a separate context, members of small progressive breakaway groups have also adopted the label.

Cultural Mormons

[edit]Cultural Mormons are individuals who may not believe in certain doctrines or practices of the institutional LDS Church yet identify as members of the Mormon ethnic identity.[142][130][143] Usually, this is a result of having been raised in the LDS faith or having converted and spent a large portion of one's life as an active member of the LDS Church.[144] Cultural Mormons may or may not be actively involved with the LDS Church. In some cases, they may not be members of the LDS Church.

Beliefs

[edit]Mormons have a scriptural canon consisting of the Bible (both Old and New Testaments), the Book of Mormon, and a collection of revelations and writings by Joseph Smith known as the Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price. Mormons, however, have a relatively open definition of scripture. As a general rule, anything spoken or written by a prophet, while under inspiration, is considered to be the word of God.[145] Thus, the Bible, written by prophets and apostles, is the word of God, so far as it is translated correctly. The Book of Mormon is also believed to have been written by ancient prophets and is viewed as a companion to the Bible. By this definition, the teachings of Smith's successors are also accepted as scripture, though they are always measured against and draw heavily from the scriptural canon.[146]

Mormons believe in "a friendly universe" governed by a God whose aim is to bring his children to immortality and eternal life.[148] Mormons have a unique perspective on the nature of God, the origin of man, and the purpose of life. For instance, Mormons believe in a pre-mortal existence where people were literal spirit children of God[149] and that God presented a plan of salvation that would allow his children to progress and become more like him. The plan involved the spirits receiving bodies on earth and going through trials in order to learn, progress, and receive a "fullness of joy".[149] The most important part of the plan involved Jesus, the eldest of God's children, coming to earth as the literal Son of God to conquer sin and death so that God's other children could return. According to Mormons, every person who lives on earth will be resurrected, and nearly all of them will be received into various kingdoms of glory.[150] To be accepted into the highest kingdom, a person must fully accept Christ through faith, repentance, and through ordinances such as baptism and the laying on of hands.[151]

According to Mormons, a deviation from the original principles of Christianity, referred to by them as The Great Apostasy, occurred after the ascension of Jesus Christ,[152] marked by the corruption of Christian doctrine by Greek and other philosophies,[153][154] Members state the martyrdom of the apostles[155] led to a loss of priesthood authority to administer the church and its ordinances.[156] Mormons believe that God restored the early Christian church through Joseph Smith. In particular, Mormons believe that angels such as Peter, James, John, John the Baptist, Moses, and Elijah appeared to Smith and others and bestowed various priesthood authorities on them. Mormons believe that their church is the "only true and living church" because of the divine authority restored through Smith. Mormons self-identify as being Christian,[157] while many Christians, particularly evangelical Protestants, disagree with this view.[158] Mormons view other religions as having portions of the truth, doing good works, and having genuine value.[159]

The LDS Church has a top-down hierarchical structure with a president–prophet dictating revelations for the entire church. Lay members are also believed to have access to inspiration and are encouraged to seek their own personal revelations.[160] Mormons see Joseph Smith's First Vision as proof that the heavens are open and that God answers prayers, and place considerable emphasis on asking God to find out if something is true. Most Mormons do not assert to have had heavenly visions like Smith's in response to prayers, but believe God talks to them in their hearts and minds through the Holy Ghost. According to Richard Lyman Bushman, members have some beliefs that are considered strange in a modernized world, but they continue to hold onto their beliefs because they feel God has spoken to them.[161]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The term "Latter-day" refers to the last dispensation,[10][11] and "Saints" is the same denomination used at the time of Jesus in the New Testament.[12][13]

References

[edit]- ^ "2023 Statistical Report of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024. (The LDS Church claimed a membership of 17,255,394 in 2023, and the Community of Christ claimed around 250,000 in 2020.)

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - United States". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Mexico". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Brazil". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Philippines". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Peru". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Chile". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Argentina". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Facts and Statistics - Guatemala". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. April 6, 2024. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "The Last Dispensation". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ "The Church of Jesus Christ in Former Times". Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Acts 9:13;32;41". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ "Acts 26:10". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Criss, Doug (August 17, 2018). "Mormons don't want you calling them Mormons anymore". CNN. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life 2012, p.10: Mormons are nearly unanimous in describing Mormonism as a Christian religion, with 97% expressing this point of view

- ^ Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry (CARM), Is Mormonism Christian? Archived February 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, accessed February 27, 2016

- ^ "Are Mormons Christian?". Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "2021 Statistical Report for 2022 April Conference". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Newsroom. Retrieved April 2, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ The LDS Church has taken the position that the term Mormon should only apply to the LDS Church and its members, and not other adherents who have adopted the term. (See: "Style Guide – The Name of the Church". LDS Newsroom. April 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2011.) The Church cites the AP Stylebook, which states, "The term Mormon is not properly applied to the other Latter Day Saints churches that resulted from the split after [Joseph] Smith's death." ("Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, The", Associated Press, The Associated Press Stylebook and Briefing on Media Law, 2002, ISBN 0-7382-0740-3, p.48) Despite the LDS Church's position, the term Mormon is widely used by journalists and non-journalists to refer to adherents of Mormon fundamentalism.

- ^ "The Original Intention Behind the Term Mormon". Mormon Scholar. November 22, 2018. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "From the Illinois State Register" (PDF). No. 2. The Pioneer. November 13, 1844. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Jacobs, Julia (August 18, 2018). "Stop Saying 'Mormon,' Church Leader Says. But Is the Real Name Too Long?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ On August 18, 2018, church president Russell M. Nelson asked followers and non-followers to characterize the denomination with the name "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" instead of "Mormons", "Mormonism" or the shorthand of "LDS"."Latter Day Saints church leader rejects 'Mormon' label". BBC News. August 18, 2018. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Stack, Peggy Fletcher (August 22, 2018). "LDS Church wants everyone to stop calling it the LDS Church and drop the word 'Mormons' — but some members doubt it will happen". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Shields, Steven L. (2014). "The Early Community of Christ Mission to "Redeem" the Church in Utah". Journal of Mormon History. 40 (4): 158–170. doi:10.5406/jmormhist.40.4.158. S2CID 246562695.

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 75, 119).

- ^ A Mormon scripture describing the ancient city of Enoch became a model for the Saints. Enoch's city was a Zion "because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there were no poor among them" Bushman (2008, pp. 36–38); (Book of Moses 7:18).

- ^ "In Missouri and Illinois, Zion had been a city; in Utah, it was a landscape of villages; in the urban diaspora, it was the ward with its extensive programs." Bushman (2008, p. 107).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 19).

- ^ Scholars and eye-witnesses disagree as to whether the church was organized in Manchester, New York at the Smith log home, or in Fayette at the home of Peter Whitmer Sr. Bushman (2005, p. 109); Marquardt (2005, pp. 223–23) (arguing that organization in Manchester is most consistent with eye-witness statements).

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 1, 9); O'Dea (1957, p. 9); Persuitte, David (October 2000). Joseph Smith and the Origins of the Book of Mormon. McFarland. p. 30. ISBN 9780786484034. Retrieved January 25, 2012..

- ^ a b LDS Church (2010). "Joseph Smith Home Page/Mission of the Prophet/First Vision: This Is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!". Retrieved April 29, 2010.; Allen (1966, p. 29) (belief in the First Vision now considered second in importance only to belief in the divinity of Jesus.); Hinkley, Gordon B. (1998). "What Are People Asking about Us?". Ensign (November). Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2019. ("[N]othing we teach, nothing we live by is of greater importance than this initial declaration.").

- ^ O'Dea (1957, p. 41) (by the next spring the church had 1,000 members).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 97) (citing letter by Smith to Kirtland converts, quoted in Howe (1834, p. 111)); O'Dea (1957, p. 41).

- ^ Smith et al. (1835, p. 154); Bushman (2005, p. 162); Brodie (1971, p. 109).

- ^ Smith said in 1831 that God intended the Mormons to "retain a strong hold in the land of Kirtland, for the space of five years." (Doctrine and Covenants 64:21); Bushman (2005, p. 122).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 222–27); Brodie (1971, p. 137) (noting that the brutality of the Jackson Countians aroused sympathy for the Mormons and was almost universally deplored by the media); O'Dea (1957, pp. 43–45) (The Mormons were forced out in a November gale, and were taken in by Clay County residents, who earned from non-Mormons the derogative title of "Jack Mormons").

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 141, 146–59); Bushman (2005, p. 322).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 101); Arrington (1992, p. 21) (by summer of 1835, there were 1500 to 2000 Saints in Kirtland); Desert Morning News 2008 Church Almanac p. 655 (from 1831 to 1838, church membership grew from 680 to 17,881); (Bushman 2005, pp. 310–19) (The Kirtland Temple was viewed as the site of a new Pentecost); (Brodie 1971, p. 178). Smith also published several new revelations during the Kirtland era.

- ^ O'Dea (1957, p. 45) (In December 1836, the Missouri legislature granted the Mormons the right to organize Caldwell County).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 328–38); Brooke (1994, p. 221) ("Ultimately, the rituals and visions dedicating the Kirtland temple were not sufficient to hold the church together in the face of a mounting series of internal disputes.")

- ^ Roberts (1905, p. 24) (referring to the Far West church as the "church in Zion"); (Bushman 2005, p. 345) (The revelation calling Far West "Zion" had the effect of "implying that Far West was to take the place of Independence.")

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 357–64); Brodie (1971, pp. 227–30); Remini (2002, p. 134); Quinn (1994, pp. 97–98).

- ^ (Bushman 2005, p. 367) (Boggs' executive order stated that the Mormon community had "made war upon the people of this State" and that "the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace"). (Bushman 2005, p. 398) (In 1976, Missouri issued a formal apology for this order) O'Dea (1957, p. 47).

- ^ O'Dea (1957, p. 47) ("the Saints, after being ravaged by troops, robbed by neighbors, and insulted by public officials from February to April, crossed over into Illinois").

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 383–84).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 409); Brodie (1971, pp. 258, 264–65); O'Dea (1957, p. 51) (noting the city growth and missionary success in England).

- ^ Widmer (2000, p. 119) (Smith taught that faithful Mormons may progress until they become co-equal with God); Roberts (1909, pp. 502–03); Bushman (2005, pp. 497–98) (the second anointing provided a guarantee that participants would be exalted even if they sinned).

- ^ Initially, Smith introduced plural marriage only to his closest associates.Brodie (1971, pp. 334–36); Bushman (2005, pp. 437, 644) The practice was acknowledged publicly in 1852 by Brigham Young.

- ^ Quinn 1980, pp. 120–122, 165; Bushman (2005, pp. 519–21) (describing the Council of Fifty).

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 30) The first extant account of the First Vision is the manuscript account in Joseph Smith, "Manuscript History of the Church" (1839); the first published account is Orson Pratt, An Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions and of the Late Discovery of Ancient American Records (Edinburgh: Ballantyne and Hughes, 1840); and the first American publication is Smith's letter to John Wentworth in Times and Seasons, 3 (March 1842), 706–08. (These accounts are available in Vogel, Dan, ed. (1996). Early Mormon Documents. Vol. 1. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-072-4..) As the LDS historian Richard Bushman wrote in his biography of Smith, "At first, Joseph was reluctant to talk about his vision. Most early converts probably never heard about the 1820 vision." Bushman (2005, p. 39).

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 64–67)

- ^ Encyclopedia of Latter-Day Saint History, p. 824; Brodie (1971, pp. 393–94); Bushman (2005, pp. 539–50); Many local Illinoisans were uneasy with Mormon power, and their unease was fanned by the local media after Smith suppressed a newspaper containing an exposé regarding plural marriage, theocracy, and other sensitive and oft misinterpreted issues. The suppression resulted in Smith being arrested, tried, and acquitted for "inciting a riot". On June 25, Smith let himself be arrested and tried for the riot charges again, this time in Carthage, the county seat, where he was incarcerated without bail on a new charge of treason. Bentley, Joseph I. (1992), "Smith, Joseph: Legal Trials of Joseph Smith", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 1346–1348, ISBN 978-0-02-879602-4, OCLC 24502140, archived from the original on November 15, 2014, retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Brigham Young later said of Hyrum, "Did Joseph Smith ordain any man to take his place. He did. Who was it? It was Hyrum, but Hyrum fell a martyr before Joseph did. If Hyrum had lived he would have acted for Joseph." Times and Seasons, 5 [October 15, 1844]: 683.

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 143); Brodie (1971, p. 398).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 556–57).

- ^ Smith's position as President of the Church was originally left vacant, based on the sentiment that nobody could succeed Smith's office. Years later, the church established the principle that Young, and any other senior apostle of the Quorum of the Twelve, would be ordained President of the Church as a matter of course upon the death of the former President, subject to unanimous agreement of the Quorum of the Twelve.

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 198–211).

- ^ In 2004, the State of Illinois recognized the expulsion of the Latter-day Saints as the "largest forced migration in American history" and stated in the adopted resolution that, "WHEREAS, The biases and prejudices of a less enlightened age in the history of the State of Illinois caused unmeasurable hardship and trauma for the community of Latter-day Saints by the distrust, violence, and inhospitable actions of a dark time in our past; therefore, be it RESOLVED, BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE NINETY-THIRD GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, that we acknowledge the disparity of those past actions and suspicions, regretting the expulsion of the community of Latter-day Saints, a people of faith and hard work." Illinois General Assembly (April 1, 2004). "Official House Resolution HR0793 (LRB093 21726 KEF 49525 r)". Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2011.; "The great Mormon migration of 1846–1847 was but one step in the Mormons' quest for religious freedom and growth." "Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail: History & Culture", NPS.gov, National Park Service, archived from the original on December 8, 2014, retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ O'Dea (1957, p. 86) ("Having failed to build Zion within the confines of American society, the Latter-day Saints found in the Great Basin the isolation that would enable them to establish a distinctive community based upon their own beliefs and values").

- ^ O'Dea (1957, p. 84) (From 1847 to 1857 ninety-five Mormon communities were established, most of them clustering around Salt Lake City); Hunter, Milton (June 1939). "The Mormon Corridor". Pacific Historical Review. 8 (2): 179–200. doi:10.2307/3633392. JSTOR 3633392..

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 86–89).

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 87–91).

- ^ a b O'Dea (1957, p. 91).

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 91–92); "Welsh Mormon History", WelshMormon.BYU.edu, Center for Family History and Genealogy, Brigham Young University, archived from the original on July 14, 2014, retrieved July 10, 2014 During the 1840s and 1850s many thousands of Welsh Mormon converts immigrated to America, and today, it is estimated that around 20 percent of the population of Utah is of Welsh descent.

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 95–96).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 88) (Plural marriage originated in a revelation that Joseph Smith apparently received in 1831 and wrote down in 1843. It was first publicly announced in a general conference in 1852); Embry, Jessie L. (1994), "Polygamy", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 978-0-87480-425-6, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on April 17, 2017, retrieved October 31, 2013 The Mormon doctrine of plural wives was officially announced by one of the Twelve Apostles, Orson Pratt, and Young in a special conference of the elders of the LDS Church assembled in the Mormon Tabernacle on August 28, 1852, and reprinted in an extra edition of the Deseret News "Minutes of conference: a special conference of the elders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints assembled in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, August 28, 1852, 10 o'clock, a.m., pursuant to public notice". Deseret News Extra. September 14, 1852. p. 14.. See also The 1850s: Official sanction in the LDS Church

- ^ Flake, Kathleen (2004). The Politics of American Religious Identity. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 65, 192. ISBN 978-0-8078-5501-0..

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 88) (If asked why they entered these relationships, both plural wives and husbands emphasized spiritual blessings of being sealed eternally and of submitting to God's will. According to the federal censuses, the highest percentage of the population in polygamous families was in 1860 (43.6 percent) and it declined to 25 percent in 1880 and to 7 percent in 1890).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 88) ("The close study of the marriages in one nineteenth-century Utah community revealed that a disproportionate number of plural wives were women who arrived in Utah without fathers or brothers to care for them...Since better-off men more frequently married plurally, the practice distributed wealth to the poor and disconnected").

- ^ Tullidge, Edward (1886), "Resignation of Judge Drummond", History of Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City: Star Printing Company, pp. 132–35, OCLC 13941646

- ^ O'Dea (1957, pp. 101–02); Bushman (2008, p. 95).

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 96–97) (calling the Mountain Meadows massacre the greatest tragedy in Mormon history).

- ^ To combat the notion that rank-and-file Mormons were unhappy under Young's leadership, Cumming noted that he had offered to help any to leave the territory if they desired. Of the 50,000 inhabitants of the state of Utah, the underwhelming response—56 men, 33 women, and 71 children, most of whom stated they left for economic reasons—impressed Cumming, as did the fact that Mormon leaders contributed supplies to the emigrants. Cumming to [Secretary of State Lewis Cass], written by Thomas Kane, May 2, 1858, BYU Special Collections.

- ^ Firmage, Edwin Brown; Mangrum, Richard Collin (2002). Zion in the Courts: A Legal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1830–1900. U. of Illinois Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-252-06980-2..

- ^ a b Bushman (2008, p. 97).

- ^ Official Declaration 1

- ^ "Style Guide – The Name of the Church: Topics and Background", MormonNewsroom.org, LDS Church, April 9, 2010, archived from the original on June 13, 2019, retrieved July 9, 2014,

When referring to people or organizations that practice polygamy, it should be stated that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not affiliated with polygamous groups.

. The church repudiates polygamist groups and excommunicates their members if discovered: Bushman (2008, p. 91); "Mormons seek distance from polygamous sects". NBCNews.com. AP. June 26, 2008. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.. - ^ Bushman (2008, p. 103).

- ^ Mauss (1994, p. 22). "With the consistent encouragement of church leaders, Mormons became models of patriotic, law-abiding citizenship, sometimes seeming to "out-American" all other Americans. Their participation in the full spectrum of national, social, political, economic, and cultural life has been thorough and sincere".

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 105).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 106).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 53).

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 40–41).

- ^ The term peculiar people is consciously borrowed from 1 Peter 2:9, and can be interpreted as "special" or "different", though Mormons have certainly been viewed as "peculiar" in the modern sense as well. Mauss (1994, p. 60).

- ^ "Developments mitigating traditional racial, ethnic, and gender inequality and bigotry were regarded in hindsight by most Americans (and most Mormons) as desirable .... On the other hand, Mormons (and many others) have watched with increasing alarm the spread throughout society of 'liberating' innovations such as the normalization of non-marital sexual behavior, the rise in abortion, illegitimacy, divorce, and child neglect or abuse, recreational drugs, crime, etc." Mauss (1994, p. 124).

- ^ "[T]he church appears to have arrested, if not reversed, the erosion of distinctive Mormon ways that might have been anticipated in the 60s." Mauss (1994, p. 140). "However, in partial contradiction to their public image, Mormons stand mostly on the liberal side of the continuum on certain other social and political issues, notably on civil rights, and even on women's rights, except where these seem to conflict with child-rearing roles." Mauss (1994, p. 156).

- ^ Mauss, Armand L. (2003). All Abraham's Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage. University of Illinois Press. pp. 213–215. ISBN 978-0-252-02803-8.; Bushman (2008, pp. 111–12) ("The origins of this policy are not altogether clear. "Passages in Joseph Smith's translations indicate that a lineage associated with Ham and the Egyptian pharaohs was forbidden the priesthood. Connecting the ancient pharaohs with modern Africans and African Americans required a speculative leap, but by the time of Brigham Young, the leap was made.")

- ^ a b Bushman (2008, pp. 111–12).

- ^ "1999–2000 Church Almanac". Adherents.com: 119. 1998. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011. "A rough estimate would place the number of Church members with African roots at year-end 1997 at half a million, with about 100,000 each in Africa and the Caribbean, and another 300,000 in Brazil."

- ^ "The Church Continues to Grow in Africa". Genesis Group. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012.

- ^ Newell G. Bringhurst, Darron T. Smith (December 13, 2005). Black and Mormon. University of Illinois Press. pp. 102–104.

- ^ Armand L. Mauss (1994), The angel and the beehive: the Mormon struggle with assimilation, University of Illinois Press, p. 92, ISBN 9780252020711; "Building a bigger tent: Does Mormonism have a Mitt Romney problem?", The Economist, February 25, 2012, archived from the original on February 27, 2012, retrieved February 27, 2012 (In 2010 alone the church grew by 400,000 new members, including converts and newborns).

- ^ Todd, Jay M. (March 1996). "More Members Now outside U.S. Than in U.S". Ensign. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "2012 Statistical Report for 2013 April General Conference". April 6, 2013. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ In 2011, approximately 6.2 million of the church's 14.4 million members lived in the U.S. "Facts and Statistics: United States". LDS Newsroom. December 2011. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2018..

- ^ Stack, Peggy Fletcher (January 10, 2014), "New almanac offers look at the world of Mormon membership", The Salt Lake Tribune, archived from the original on October 21, 2014, retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ "Mormons in America". Pew Research Center. January 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012..

- ^ Daniel Reeves (2009). "The Global Distribution of Adventists and Mormons in 2007" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011..

- ^ a b Thomas W. Murphy (1996). "Reinventing Mormonism: Guatemala as Harbinger of the Future?" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ "2019 Statistical Report for April 2020 Conference" Archived June 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Church Newsroom, April 4, 2020.

- ^ "LDS Statistics and Church Facts – Total Church Membership". www.mormonnewsroom.org. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Bushman (2008, p. 47).

- ^ "Sacrament". churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ a b "For the Strength of Youth: Fulfilling Our Duty to God". LDS Church.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "USA–Utah". LDS Newsroom. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2011..

- ^ Mauss often compares Salt Lake City Mormons to California Mormons from San Francisco and East Bay. The Utah Mormons were generally more orthodox and conservative. Mauss (1994, pp. 40, 128); A Portrait of Mormons in the U.S.: III. Social and Political Views (Report). Pew Research Center. July 24, 2009. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011..

- ^ Newport, Frank (January 11, 2010). Mormons Most Conservative Major Religious Group in U.S.: Six out of 10 Mormons are politically conservative (Report). Gallup poll. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011.; Pond, Allison (July 24, 2009). A Portrait of Mormons in the U.S (Report). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011..

- ^ Early Mormons had practiced the law of consecration in Missouri for two years, in an attempt to eliminate poverty. Families would return their surplus "income" to the bishop, who would then redistribute it among the saints. Though initial efforts at "consecration" failed, consecration has become a more general attitude that underlies Mormon charitable works. Bushman (2008, pp. 36–39).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 53) (The name "stake" comes from a passage in Isaiah that compares Zion to a tent that will enlarge as new stakes are planted); See Isaiah 33:20 and Isaiah 54:2.

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 35, 52)

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 39)

- ^ A full-time mission is looked upon as important character training for a young man. O'Dea (1957, p. 177).

- ^ Stack, Peggy Fletcher (August 31, 2012). "It's Official: Coke and Pepsi are OK for Mormons". Washington Post. (Religion News Service). Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013..

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants, section 89".

- ^ "Word of Wisdom". True to the Faith. 2004. pp. 186–88. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ February 2007 All Is Safely Gathered In: Family Home Storage Archived March 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 59) (In the temple, husbands and wives are sealed to each other for eternity. The implication is that other institutional forms, including the church, might disappear, but the family will endure); Mormons in America (Report). Pew Research Center. January 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012. (A 2011 survey of Mormons in the United States showed that family life is very important to Mormons, with family concerns significantly higher than career concerns. Four out of five Mormons believe that being a good parent is one of the most important goals in life, and roughly three out of four Mormons put having a successful marriage in this category); "New Pew survey reinforces Mormons' top goals of family, marriage". Deseret News. January 12, 2012. Archived from the original on January 16, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012.; See also: "The Family: A Proclamation to the World".

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 30–31); Bushman (2008, p. 58).

- ^ "Chastity". True to the Faith. 2004. pp. 29–33.; Mormons in America (Report). Pew Research Center. January 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012. (79% of Mormons in the US say that sex between unmarried adults is morally wrong, far higher than the 35% of the general public who hold the same view).

- ^ "Topic: Abortion". churchofjesuschrist.org. November 8, 2012. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020..

- ^ "Dress and Appearance". For the Strength of the Youth. LDS Church. 2001. Retrieved November 15, 2011.[dead link] "What are the biggest changes to the new 'For the Strength of Youth' booklet?". LDSLiving. 2022. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ Homosexual acts (as well as other sexual acts outside the bonds of marriage) are prohibited by the law of chastity. Violating the law of chastity may result in excommunication. Gordon B. Hinckley (1998). "What Are People Asking about Us?". Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2011..

- ^ "Resources for Individuals", EvergreenInternational.org, Evergreen International, archived from the original on November 20, 2012.

- ^ Rebecca Rosen Lum (August 20, 2007). "Mormon church changes stance on homosexuality; New teachings say lifelong celibacy to be rewarded with heterosexuality in heaven". The Oakland Tribune. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2007..

- ^ "Mormons and Gays". The Church of Jesus Christ Latter-day Saints. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2013..

- ^ "North Star LDS Community". North Star. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ Paul Mortensen. "In The Beginning: A Brief History of Affirmation". Affirmation: Gay & Lesbian Mormons. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013.; See also:Affirmation: Gay & Lesbian Mormons.

- ^ As of the end of 2015, the LDS Church reported a membership of over 15 million ("2015 Statistical Report for 2016 April General Conference". April 2, 2016. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.). Most other Brigham Young–lineage sects number in the tens of thousands. Historically, the Latter Day Saint movement has been dominated by the LDS Church, with over 95 percent of adherents. One denomination dominates the non-LDS Church section of the movement: the Community of Christ, which has about 250,000 members.)

Also note the use of the lower case d and hyphen in "Latter-day Saints", as opposed to the larger "Latter Day Saint movement". - ^ a b c Stack, Peggy Fletcher (September 23, 2011). "Active, inactive – do Mormon labels work or wound?". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013..

- ^ Member activity rates are estimated from missionary reports, seminary and institute enrollment, and ratio of members per congregation – "Countries of the World by Estimated Member Activity Rate". LDS Church Growth. July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2011.; See also: Stan L. Albrecht (1998). "The Consequential Dimension of Mormon Religiosity". Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.; Stack, Peggy Fletcher (July 26, 2005). "Keeping members a challenge for LDS church". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Cunningham, Perry H. (1992), "Activity in the Church", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 13–15, ISBN 978-0-02-879602-4, OCLC 24502140, archived from the original on August 5, 2021, retrieved September 18, 2020

- ^ Stan L. Albrecht (1998). "The Consequential Dimension of Mormon Religiosity". Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Hatch, Heidi (May 10, 2017). "KUTV". Archived from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ Lipka, Michael (May 12, 2015). "Millennials increasingly are driving growth of 'nones'". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ Martha Sonntag Bradley, "Polygamy-Practicing Mormons" in J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann (eds.) (2002). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia 3:1023–24; Dateline NBC, January 2, 2001; Ken Driggs, "Twentieth-Century Polygamy and Fundamentalist Mormons in Southern Utah" Archived February 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Winter 1991, pp. 46–47; Irwin Altman, "Polygamous Family Life: The Case of Contemporary Mormon Fundamentalists", Utah Law Review (1996) p. 369; Stephen Eliot Smith, "'The Mormon Question' Revisited: Anti-Polygamy Laws and the Free Exercise Clause", LL.M. thesis, Harvard Law School, 2005.

- ^ "Style Guide". LDS Newsroom. April 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

When referring to people or organizations that practice polygamy, it should be stated that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not affiliated with polygamous groups.

; The church repudiates polygamist groups and excommunicates their members if discovered – Bushman (2008, p. 91); "Mormons seek distance from polygamous sects". NBC News. 2008. Archived from the original on November 2, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2014. - ^ Quinn, Michael D. (Summer 1998). "Plural Marriage and Mormon Fundamentalism" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 31 (2): 7. doi:10.2307/45226443. JSTOR 45226443. S2CID 254325184. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ "LiberalMormon.net". Archived from the original on December 12, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011..

- ^ "Where does the term 'Jack-Mormon' come from?". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ Chris H (September 21, 2010). "Bringing back Liberal Mormonism". Main Street Plaza. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011..

- ^ Murphy, Thomas W. (1999). "From Racist Stereotype to Ethnic Identity: Instrumental Uses of Mormon Racial Doctrine". Ethnohistory – Duke University Press. 46 (3): 451–480. JSTOR 483199.

- ^ Campbell, David E. (2014). Mormons and American politics : seeking the promised land: Part I – Mormons as an Ethno-Religious Group. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781139227247. OCLC 886644501.

- ^ Rogers, Peggy, "New Order Mormon Essays: The Paradox of the Faithful Unbeliever", New Order Mormon, NewOrderMormon.org, Publisher is anonymous, archived from the original on October 2, 2015, retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Kent P. (1992), "Scriptures: Authority of Scripture", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 1280–1281, ISBN 978-0-02-879602-4, OCLC 24502140, archived from the original on February 3, 2016, retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 25–26).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 8) ("As the name of the church ... suggests, Jesus Christ is the premier figure. Smith does not even play the role of the last and culminating prophet, as Muhammad does in Islam"); "What Mormons Believe About Jesus Christ". LDS Newsroom. Retrieved November 11, 2011.; In a 2011 Pew Survey a thousand Mormons were asked to volunteer the one word that best describes Mormons. The most common response from those surveyed was "Christian" or "Christ-centered".

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 79).

- ^ a b "Plan of Salvation". True to the Faith: A Gospel Reference: 115. 2004.

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 75).

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 78); In Mormonism, an ordinance is a formal act, in which people enter into covenants with God. For example, covenants associated with baptism and the Eucharist involve taking the name of the Son upon themselves, always remembering him, and keeping his commandments; "Atonement of Jesus Christ". True to the Faith: A Gospel Reference: 14. 2004.; Bushman (2008, pp. 60–61) Because Mormons believe that everyone must receive certain ordinances to be saved, Mormons perform vicarious ordinances such as baptism for the dead on behalf of deceased persons. Mormons believe that the deceased may accept or reject the offered ordinance in the spirit world.

- ^ Missionary Department of the LDS Church (2004). Preach My Gospel. LDS Church, Inc. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-402-36617-1.

- ^ Talmage, James E. (1909). The Great Apostasy. The Deseret News. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-87579-843-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Richards, LeGrand (1976). A Marvelous Work and a Wonder. Deseret Book Company. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-87747-161-5.

- ^ Talmage, James E. (1909). The Great Apostasy. The Deseret News. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-87579-843-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Eyring, Henry B. (May 2008). "The True and Living Church". Ensign: 20–24.; Cf. John 14:16–17 Archived July 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine and 16:13 Archived October 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Acts 2:1–4 Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, and Galatians 1:6–9 Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mormonism in America (Report). Pew Research Center. January 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012. (Mormons are nearly unanimous in describing Mormonism as a Christian religion, with 97% expressing this point of view); Robinson, Stephen E. (May 1998), "Are Mormons Christians?", New Era, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

- ^ Romney's Mormon Faith Likely a Factor in Primaries, Not in a General Election (Report). Pew Research Center. November 23, 2011. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012. (About a third of Americans and half of evangelical Protestants view Mormonism as a non-Christian religion).

- ^ "Have the Presbyterians any truth? Yes. Have the Baptists, Methodists, etc., any truth? Yes. They all have a little truth mixed with error. We should gather all the good and true principles in the world and treasure them up, or we shall not come out true 'Mormons'." Joseph Fielding Smith (1993). Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. p. 316.; Mormons take an inclusivist position that their religion is correct and true but that other religions have genuine value. Palmer; Keller; Choi; Toronto (1997). Religions of the World: A Latter-day Saint View. Brigham Young University..

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 54).

- ^ Bushman (2008, pp. 15, 35–35) (Outside observers sometimes react to Mormonism as "nice people, wacky beliefs." Mormons insist that the "wacky" beliefs pull them together as a people and give them the strength and the know-how to succeed in the modern world).

Sources

[edit]- Allen, James B. (1966), "The Significance of Joseph Smith's First Vision in Mormon Thought", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 1 (3): 28–45, doi:10.2307/45223817, JSTOR 45223817, S2CID 222223353.

- Arrington, Leonard J. (1992), The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-Day Saints, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-06236-0.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971). No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-46967-6.

- Brooke, John L. (1994). The Refiner's Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34545-6.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4270-8.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2008). Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531030-6.

- Marquardt, H. Michael (2005). The Rise of Mormonism, 1816–1844. Xulon Press.

- Howe, Eber Dudley, ed. (1834), Mormonism Unvailed, Painesville, Ohio: Telegraph Press.

- Mauss, Armand (1994). The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02071-1.

- O'Dea, Thomas F. (1957). The Mormons. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-61743-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Quinn, D. Michael (1980), "The Council of Fifty and Its Members, 1844 to 1945", BYU Studies, 20 (2): 163–98, archived from the original on October 21, 2013, retrieved December 22, 2023.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1994). The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-056-4.

- Remini, Robert V. (2002). Joseph Smith. Penguin Lives. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-03083-X.

- Roberts, B. H., ed. (1905), History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, vol. 3, Salt Lake City: Deseret News.

- Roberts, B. H., ed. (1909), History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, vol. 5, Salt Lake City: Deseret News.

- Shipps, Jan (1985). Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01417-8.

- Smith, Joseph; Cowdery, Oliver; Rigdon, Sidney; Williams, Frederick G. (1835), Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints: Carefully Selected from the Revelations of God, Kirtland, Ohio: F. G. Williams & Co, archived from the original on May 20, 2012, retrieved December 22, 2023.

- Widmer, Kurt (2000). Mormonism and the Nature of God: A Theological Evolution, 1830–1915. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0776-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Alexander, Thomas G. (1980). "The Reconstruction of Mormon Doctrine: From Joseph Smith to Progressive Theology" (PDF). Sunstone. 5 (4): 24–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- Bloom, Harold (1992). The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (1st ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-67997-2.

- Bowman, Matthew (2012). The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-64491-0.

- Epperson, Steven (1999). "Mormons". In Barkan, Elliott Robert (ed.). A notion of peoples: a sourcebook on America's multicultural heritage. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29961-2.

- Fraser, John (1883). . In Baynes, T. S.; Smith, W. R. (eds.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XVI (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hill, Marvin S. (1989). Quest for Refuge: The Mormon Flight from American Pluralism. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 9780941214704.

- Ludlow, Daniel H., ed. (1992). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-904040-9.

- May, Dean (1980). "Mormons". In Thernstrom, Stephan (ed.). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 720.

- McMurrin, Sterling M. (1965). The Theological Foundations of the Mormon Religion. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-135-6.

- Ostling, Richard; Ostling, Joan K. (2007). Mormon America: The Power and the Promise. New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-143295-8.

- Shipps, Jan (2000). Sojourner in the promised land: forty years among the Mormons. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02590-7.

External links

[edit]- churchofjesuschrist.org Archived June 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine and comeuntochrist.org Archived May 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, official websites of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- The Mormons (PBS documentary series)