Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

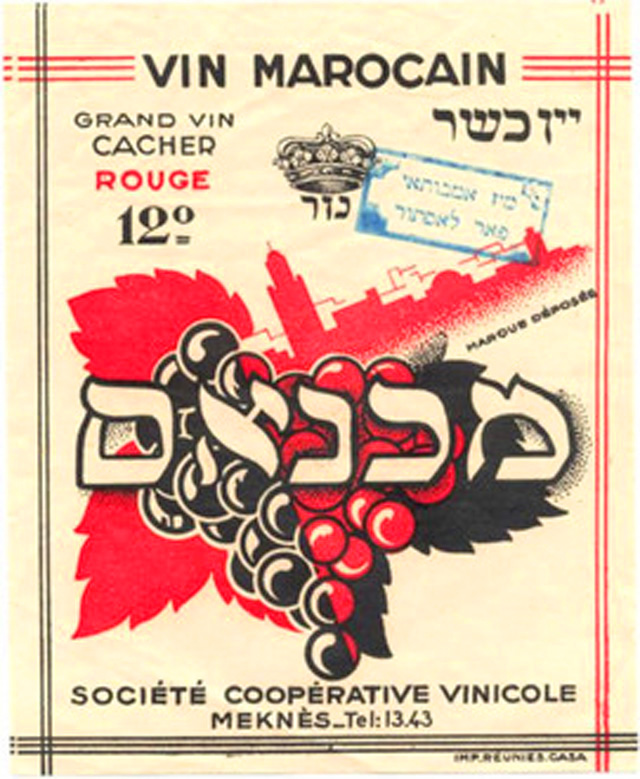

Kosher wine

View on Wikipedia Kosher wine label from 1930 | |

| Halakhic texts relating to this article | |

|---|---|

| Torah: | Deuteronomy 32:38 |

| Mishnah: | Avodah Zarah 29b |

| Babylonian Talmud: | Avodah Zarah 30a |

Kosher wine (Hebrew: יין כשר, romanized: yáyin kashér) is wine that is produced in accordance with halakha, and more specifically kashrut, such that Jews will be permitted to pronounce blessings over and drink it. This is an important issue, since wine is used in several Jewish ceremonies, especially those of Kiddush.

To be considered kosher, Sabbath-observant Jews must supervise the entire winemaking process and handle much of it in person, from the time the grapes are loaded into the crusher until the finished wine product is bottled and sealed. Additionally, any ingredients used, including finings, must be kosher.[1] Wine that is described as "kosher for Passover" must have been kept free from contact with leavened or fermented grain products, a category that includes many industrial additives and agents.[2]

When kosher wine is produced, marketed, and sold commercially, it would normally have a hechsher (kosher certification mark) issued by a kosher certification agency, or by an authoritative rabbi who is respected and known to be learned in Jewish law, or by the Kashruth Committee working under a beth din (rabbinical court of Judaism).

In recent times, there has been an increased demand for kosher wines, and a number of wine-producing countries now produce a wide variety of sophisticated kosher wines under strict rabbinical supervision, particularly in Israel, the United States, France, Germany, Italy, South Africa, Chile,[3] and Australia. Two of the world's largest producers and importers of kosher wines—Kedem and Manischewitz—are both based in the American Northeast.

History

[edit]

The use of wine has a long history in Judaism, dating back to biblical times. Archeological evidence shows that wine was produced throughout ancient Israel. The traditional and religious use of wine continued within the Jewish diaspora community. In the United States, kosher wines came to be associated with sweet Concord wines produced by wineries founded by Jewish immigrants to New York.

Beginning in the 1980s, a trend towards producing dry, premium-quality kosher wines began with the revival of the Israeli wine industry. Today kosher wine is produced not only in Israel but throughout the world, including premium wine areas like Napa Valley and the Saint-Émilion region of Bordeaux.[2]

Role of wine in Jewish holidays and rituals

[edit]It has been one of history's cruel ironies that the blood libel---accusations against Jews using the blood of murdered non-Jewish children for the making of wine and matzot---became the false pretext for numerous pogroms. And due to the danger, those who live in a place where blood libels occur are halachically exempted from using [kosher] red wine, lest it be seized as "evidence" against them.[4]

Almost all Jewish holidays, especially the Passover Seder where all present drink four cups of wine, on Purim for the festive meal, and on the Shabbat require obligatory blessings (Kiddush) over filled cups of kosher wine that are then drunk. Grape juice is also suitable on these occasions. If no wine or grape juice is present on Shabbat, the blessing over challah suffices for kiddush on Friday night; for Kiddush on Shabbat morning as well as Havdalah, if there is no wine one would use "Chamar ha-medinah", literally the "drink of the country".

At Jewish marriages, circumcisions, and at redemptions of first-born ceremonies, the obligatory blessing of Borei Pri HaGafen ("Blessed are you O Lord, Who created the fruit of the vine") is almost always recited over kosher wine (or grape juice).

According to the teachings of the Midrash, the forbidden fruit that Eve ate and which she gave to Adam was the grape from which wine is derived, though others contest this and say that it was in fact a fig.[5][6] The capacity of wine to cause drunkenness with its consequent loosening of inhibitions is described by the ancient rabbis in Hebrew as nichnas yayin, yatza sod ("wine enters, [and one's personal] secret[s] exit"), similar to the Latin "in vino veritas". Another similarly evocative expression relating to wine is: Ein Simcha Ela BeBasar Veyayin—"There is no joy except through meat and wine".)

Requirements for being kosher

[edit]Because of wine's special role in many non-Jewish religions, the kashrut laws specify that wine cannot be considered kosher if it might have been used for idolatry. These laws include prohibitions on Yayin Nesekh (יין נסך – "poured wine"), wine that has been poured to an idol, and Stam Yeynam (סתם יֵינָם), wine that has been touched by someone who believes in idolatry or produced by non-Jews. When kosher wine is yayin mevushal (יין מבושל – "cooked" or "boiled"), it becomes unfit for idolatrous use and will keep the status of kosher wine even if subsequently touched by an idolater.[7]

While none of the ingredients that make up wine (alcohol, sugars, acidity and phenols) is considered non-kosher, the kashrut laws involving wine are concerned more with who handles the wine and what they use to make it.[2] For wine to be considered kosher, only Sabbath-observant Jews may handle it, from the first time in the process when a liquid portion is separated from solid waste, until the wine is pasteurized or bottles are sealed or even sold from kosher supermarkets.[8][9] Wine that is described as "kosher for Passover" must have been kept free from contact with chametz and kitnios. This would include grain, bread, and dough as well as legumes and corn derivatives.[2]

Mevushal wines

[edit]When kosher wine is mevushal (Hebrew: "cooked" or "boiled"), it thereby becomes unfit for idolatrous use and will keep the status of kosher wine even if subsequently touched by an idolater. It is not known whence the ancient Jewish authorities derived this claim; there are no records concerning "boiled wine" and its fitness for use in the cults of any of the religions of the peoples surrounding ancient Israel. Indeed, in Orthodox Christianity, it is common to add boiling water to the sacramental wine. Another opinion holds that mevushal wine was not included in the rabbinic edict against drinking wine touched by an idolater simply because such wine was uncommon in those times.

Mevushal wine is frequently used in kosher restaurants and by kosher caterers so as to allow the wine to be handled by non-Jewish or non-observant waiters.

The process of fully boiling a wine kills off most of the fine mold on the grapes, and greatly alters the tannins and flavors of the wine. Therefore, great care is taken to satisfy the legal requirements while exposing the wine to as little heat as necessary. There is significant disagreement between halachic deciders as to the precise temperature a wine must reach to be considered mevushal, ranging from 74 to 90 °C (165 to 194 °F). (At this temperature, the wine is not at a rolling boil, but it is cooking, in the sense that it will evaporate much more quickly than usual.) Cooking at the minimum required temperature reduces some of the damage done to the wine, but still has a substantial effect[further explanation needed] on quality and aging potential.[2]

A process called flash pasteurization rapidly heats the wine to the desired temperature and immediately chills it back to room temperature. This process is said to have a minimal effect on flavor, at least to the casual wine drinker.

Irrespective of the method, the pasteurization process must be overseen by mashgichim to ensure the kosher status of the wine. Generally, they will attend the winery to physically tip the fruit into the crush, and operate the pasteurization equipment. Once the wine emerges from the process, it can be handled and aged in the normal fashion.

According to Conservative Judaism

[edit]In the 1960s, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards approved a responsum ("legal ruling") by Rabbi Israel Silverman on this subject. Silverman noted that some classical Jewish authorities believed that Christians are not considered idolaters, and that their products cannot be considered forbidden in this regard. He also noted that most winemaking in the United States is fully automated. Based on 15th–19th century precedents in the responsa literature, he concluded that wines manufactured by this automated process may not be classified as wine "manufactured by gentiles", and thus are not prohibited by Jewish law. This responsum makes no attempt to change halakhah in any way, but rather argues that most American wine, made in an automated fashion, is already kosher by traditional halakhic standards. Some criticism was later made against this teshuvah, because (a) some wines are not made by automated processes but rather, at least in some steps, by hand, and (b) on rare occasions non-kosher fining ingredients are used in wine preparation. Silverman later retracted his position.

A later responsum on this subject was written by Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff and also accepted by the CJLS.[10] Dorff noted that not all wines are made by automated processes, and thus the reasoning behind Silverman's responsum was not conclusively reliable in all cases. On the other hand, Dorff points out that even if we can avoid the issue of "wine handled by a gentile", there is a separate prohibition against wine produced from wineries owned by a gentile, in which case automation is irrelevant, and all non-certified wines are prohibited. Therefore, he explored the possibility to change the halacha, arguing that the prohibition no longer applies. He cites rabbinic thought on Jewish views of Christians, also finding that most poskim refused to consign Christians to the status of idolater. Dorff then critiqued the traditional halakhic argument that avoiding such wine would prevent intermarriage. Dorff asserted, however, that those who were strict about the laws of kashrut were not likely to intermarry, and those that did not follow the laws would not care if a wine has a heksher or not. He also noted that a number of non-kosher ingredients may be used in the manufacturing process, including animal blood.

Dorff concluded a number of points including that there is no reason to believe that the production of such wines is conducted as part of pagan (or indeed, any) religious practice. Most wines have no non-kosher ingredients whatsoever. Some wines use a non-kosher ingredient as part of a fining process, but not as an ingredient in the wine as such. Dorff noted that material from this matter is not intended to infiltrate the wine product. The inclusion of any non-kosher ingredient within the wine occurs by accident, and in such minute quantities that the ingredient is nullified. All wines made in the US and Canada may be considered kosher, regardless of whether or not their production is subject to rabbinical supervision. Many foods once considered forbidden if produced by non-Jews (such as wheat and oil products) were eventually declared kosher. Based on the above points, Dorff's responsum extends this same ruling to wine and other grape-products.

However, this teshuvah also notes that this is a lenient view. Some Conservative rabbis disagree with it, e.g. Isaac Klein. As such Dorff's teshuvah states that synagogues should hold themselves to a stricter standard so that all in the Jewish community will view the synagogue's kitchen as fully kosher. As such, Conservative synagogues are encouraged to use only wines with a hekhsher, and preferably wines from Israel.

Regional kosher wine consumption

[edit]

United States

[edit]Historically, kosher wine has been associated in the US with the Manischewitz brand, which produce a sweetened wine with a distinctive taste, made of Vitis labrusca rather than V. vinifera grapes. Due to the addition of high-fructose corn syrup, the normal bottlings of Manischewitz are, for Ashkenazi Jews, not kosher during Passover by the rule of kitniyot, and a special bottling is made available. This cultural preference for a distinct, unique variety of wine dates back to Jewish settlements in early US history.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ T. Goldberg "Picking the perfect Passover wine" MSNBC, April 19th, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e J. Robinson (ed): "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, p. 383. Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ "Chile produces kosher wine". Wine Spectator. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Rutman, Rabbi Yisrael. "Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It". torah.org. Project Genesis Inc. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ Rashi On Genesis 3:7.

- ^ Rabbi Nehemiah in the Babylonian Talmud Tractate Berachot 40a and Sanhedrin 70b.

- ^ "Uncorking the Secrets of Kosher Wine". OU Kosher Certification. 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Uncorking the Secrets of Kosher Wine". Jewish Action. 11 February 2010.

- ^ "What Makes Wine Kosher?". Wine Spectator.

- ^ Elliot Dorff, "On the Use of All Wines" YD 123:1.1985 Archived 2009-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yoni Appelbaum (14 April 2011). "The 11th Plague? Why People Drink Sweet Wine on Passover". The Atlantic. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

External links

[edit]- "The Art of Kosher Wine Making", Star-K Kosher certification website.

- "Learn about Kosher Wine" Archived 11 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kosher Wine Society.

- Laws of Judaism concerning wine From the Torah and Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law.