Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

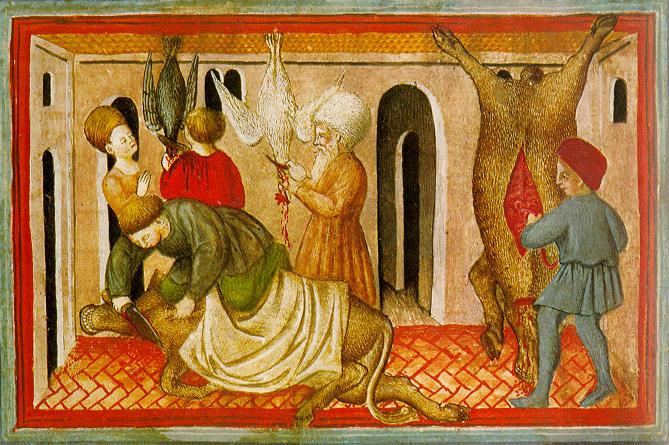

Kosher animals

View on WikipediaKosher animals are animals that comply with the regulations of kashrut and are considered kosher foods. These dietary laws ultimately derive from various passages in the Torah with various modifications, additions and clarifications added to these rules by halakha. Various other animal-related rules are contained in the 613 commandments.

Land animals

[edit]

Leviticus 11:3–8 and Deuteronomy 14:4–8 both give the same general set of rules for identifying which land animals (Hebrew: בהמות Behemoth) are ritually clean. According to these, any animal which "chews the cud" (e.g., consumes vegetation and later regurgitates it into the mouth to be re-processed and more efficiently digested) and has a completely split hoof (cloven-foot) is ritually clean, but those which only chew the cud or only have cloven hooves are unclean.

Both documents explicitly list four animals as being ritually impure:

- The camel, for chewing the cud without its hooves being divided.[1][2]

- The hyrax, for chewing the cud without having cloven hooves;[2][3] as the hyrax was not known to early English translators, the Hebrew term for this animal, שפן (shapan), has been interpreted in older English versions of the Bible as coney (rabbit, hare), a name with clear connections to words such as the Spanish conejo (rabbit). The actual coney was an exclusively European lagomorph, and not present in Canaan; hyraxes, however, are still found in Southern and Eastern Africa, the Levant and Arabian Peninsula, with the shapan in the Book of Proverbs described as having lived on rocks[4] (likely referring to the rock hyrax, not the coney). Despite their rabbit- or rodent-like appearance, hyraxes are actually one of the closest living relatives of elephants, still possessing "tusk"-like teeth—as opposed to the ever-growing, gnawing teeth of rodents or lagomorphs. Additionally, their feet do not have the small claws and digits of rodents or lagomorphs, instead resembling miniature elephant-feet, with toenails specially adapted for climbing rocks.

- The hare, for chewing the cud without having cloven hooves.[2][5]

- The pig, for having cloven hooves without chewing the cud.[6][7]

While camels possess a single stomach, and are thus not true ruminants, they do chew cud; additionally, camels do not have hooves at all, but rather separate toes on individual toe pads, with hoof-like toenails.

Although hares and other lagomorphs (coney, rabbits, pikas) do not ruminate at all, they do typically re-ingest soft cecal pellets made of chewed plant material immediately after excretion for further bacterial digestion in their stomach, which serves the same purpose as rumination. They are also known to ingest their own and the droppings of other lagomorphs for nutritive reasons.

Although not ruminants, hyraxes have complex, multichambered stomachs that allow symbiotic bacteria to break-down tough plant materials, though they do not regurgitate it for re-chewing.[8] Further clarification of this classification has been attempted by various authors, most recently by Rabbi Natan Slifkin, in a book, entitled The Camel, the Hare, and the Hyrax.[9]

Unlike Leviticus 11:3-8, Deuteronomy 14:4-8 also explicitly names 10 animals considered ritually clean:

- The ox[10]

- The sheep[10]

- The goat[10]

- The deer[11]

- The gazelle[11]

- The yahmur;[11] this term, directly taken from the Masoretic Text, is used in modern Hebrew to refer to the fallow deer, while in Arabic it refers to the roe deer.[12] Scholarship identifications of the biblical animal include, in addition to the fallow deer and roe deer, also the hartebeest,[13] based on the Vulgate, which renders it as bubalum.[14]

- The the'o;[11] this term, directly taken from the Masoretic Text, has traditionally been translated ambiguously.

- In Deuteronomy, it has traditionally been translated as wild goat, but in the same translations is called a wild ox where it occurs in Isaiah.[15] In modern Hebrew, the'o (תאו) is used for bubalus, a genus of Asiatic bovines.

- The pygarg;[11] the identity of this animal is uncertain, and pygarg is merely the Septuagint's rendering. The Masoretic Text calls it a dishon, meaning springing; it has thus usually been interpreted as some form of antelope or ibex. Specifically, Amar et al. interpret dishon as Arabian oryx.[13]

- The antelope[11]

- The camelopardalis;[11] the identity of this animal is uncertain, and "camelopardalis" is merely the Septuagint's wording.[16] The Masoretic Text calls it a zamer, but camelopardalis means camel-leopard and typically refers to the giraffe (giraffe is derived, via Italian, from the Arabic term ziraafa, meaning "assembled [from multiple parts]"); in taxonomy, several types of giraffes are placed under Giraffa camelopardalis. The traditional translation has been for the chamois, an alpine goat-antelope of Europe and parts of Asia Minor, but it has never naturally existed in Canaan; neither is the giraffe naturally found in Canaan (though it was likely known from Northern Africa). Consequently, the wild sheep ancestor, the mouflon, is considered the best remaining identification, despite not being related to the term "camel-leopard".

The Deuteronomic passages mention no further land beasts as being clean or unclean, seemingly suggesting that the status of the remaining land beasts can be extrapolated from the given rules.

By contrast, the Levitical rules later go on to add that all quadrupeds with paws should be considered ritually unclean,[17] something not explicitly stated by the Deuteronomic passages.

The Leviticus passages thus cover all the large land animals that naturally live in Canaan, except for primates, and equids (horses, zebras, etc.), which are not mentioned in Leviticus as being either ritually clean or unclean, despite their importance in warfare and society, and their mention elsewhere in Leviticus.

In an attempt to help identify animals of ambiguous appearance, the Talmud, in a similar manner to Aristotle's earlier Historia Animalium,[18] argued that animals without upper teeth would always chew the cud and have split hoofs (thus being ritually clean), and that no animal with upper teeth would do so; the Talmud makes an exception for the case of the camel (which, like the other ruminant even-toed ungulates, is apparently 'without upper teeth' though some citations[19]), even though the skulls clearly have both front and rear upper teeth. The Talmud also argues that the meat from the legs of clean animals can be torn lengthwise as well as across, unlike that of unclean animals,[unreliable source?] thus aiding to identify the status of meat from uncertain origin.[19]

Origin

[edit]Many Biblical scholars believe that the classification of animals was created to explain pre-existing taboos.[20] Beginning with Saadia Gaon, several Jewish commentators started to explain these taboos rationalistically; Saadia himself expresses an argument similar to that of totemism, that the unclean animals were declared so because they were worshipped by other cultures.[21] Due to comparatively recent discoveries about the cultures adjacent to the Israelites, it has become possible to investigate whether such principles could underlie some of the food laws.

Egyptian priests would only eat the meat of even-toed ungulates (swine, camelids, and ruminants), and rhinoceros.[22] Like the Egyptian priests, Vedic India (and presumably the Persians also) allowed the meat of rhinoceros and certain ruminants, although cattle were likely excluded as they were seemingly taboo in Vedic India;[23][24][25] in a particular parallel with the Israelite list, Vedic India explicitly forbade the consumption of camelids and domestic pigs (but not wild boar).[23][24][25] However, unlike the biblical rules, Vedic India did allow the consumption of hare and porcupine,[23][24][25] but Harran did not, and was even more similar to the Israelite regulations, allowing all ruminants (but not other land beasts) and expressly forbidding the meat of camels.[19][26]

It is also possible to find an ecological explanation for these rules. If one believes that religious customs are at least partly explained by the ecological conditions in which a religion evolves, then this too could account for the origin of these rules.[27]

Modern practices

[edit]In addition to meeting the restrictions as defined by the Torah, there is also the issue of masorah (tradition). In general, animals are eaten only if there is a masorah that has been passed down from generations ago that clearly indicates that these animals are acceptable. For instance, there was considerable debate as to the kosher status of zebu and bison among the rabbinical authorities when they first became known and available for consumption; the Orthodox Union permits bison,[28] as can be attested to by the menus of some of the more upscale kosher restaurants in New York City[citation needed].[29]

Water creatures

[edit]

Leviticus 11:9–12 and Deuteronomy 14:9–10 both state that anything residing in "the waters" (which Leviticus specifies as being the seas and rivers) is ritually clean if it has both fins and scales,[30][31] in contrast to anything residing in the waters with neither fins nor scales.[32][33] The latter class of animals is described as ritually impure by Deuteronomy,[33] Leviticus describes them as an "abomination" KJV Leviticus 11:10. Abomination is also sometimes used to translate iggul and toebah.

Although the Tanakh does not further specify, the Talmud makes the claim that all fish that have scales also have fins,[34] and so practically speaking, we need to only identify organisms that have scales and can ignore the portion of the rule about fins. Nachmanides comments that the scales of a kosher fish must be able to be removed either by hand or by knife, but that the underlying skin does not become damaged with removal of the scales,[35] and this opinion had been universally accepted by all halachic authorities at the time.[36]

Scientifically, there are five different types of fish scales: placoid, cosmoid, ganoid, ctenoid and cycloid. The majority of kosher fish exhibit the latter two forms, ctenoid or cycloid, but the bowfin (Amia calva) is an example of a fish with ganoid scales that is deemed kosher. As such, kosher status cannot be said to follow the rules of modern-day classification, and qualified experts on kosher fish must be consulted to determine the status of a particular fish or scale type.[37]

These rules restrict permissible seafood to stereotypical fish, prohibiting the unusual forms such as the eel, lamprey, hagfish, and lancelet. In addition, they exclude non-fish marine creatures, such as crustaceans (lobster, crab, prawn, shrimp, barnacle, etc.), molluscs (squid, octopus, oyster, periwinkle, etc.), sea cucumbers, and jellyfish.

Other creatures living in the sea and rivers that would be prohibited by the rules include the cetaceans (dolphin, whale, etc.), crocodilians (alligator, crocodile etc.), sea turtles, sea snakes, and all amphibians.

Sharks are considered to be ritually unclean according to these regulations, as their scales can only be removed by damaging the skin. A minor controversy arises from the fact that the appearance of the scales of swordfish is heavily affected by the ageing process—their young satisfy Nachmanides' rule, but when they reach adulthood they do not.

Traditionally "fins" has been interpreted as referring to translucent fins. The Mishnah claims that all fish with scales will also have fins, but that the reverse is not always true.[38] For the latter case, the Talmud argues that ritually clean fish have a distinct spinal column and flattish face, while ritually unclean fish don't have spinal columns and have pointy heads,[39] which would define the shark and sturgeon (and related fish) as ritually unclean.

Nevertheless, Aaron Chorin, a prominent 19th-century rabbi and reformer, declared that the sturgeon was actually ritually pure, and hence permissible to eat.[19] Many Conservative rabbis now view these particular fish as being kosher,[40] but most Orthodox rabbis do not.[36]

The question for sturgeon is particularly significant as most caviar consists of sturgeon eggs, and therefore cannot be kosher if the sturgeon itself is not. Sturgeon-derived caviar is not eaten by some Kosher-observant Jews because sturgeon possess ganoid scales instead of the usual ctenoid and cycloid scales. A vegetarian caviar substitute made from kelp has received kosher certification.[41] Atlantic salmon roe is also kosher.[42]

Origin

[edit]Nachmanides believed that the restrictions against certain fish also addressed health concerns, arguing that fish with fins and scales (and hence ritually clean) typically live in shallower waters than those without fins or scales (i.e., those that were ritually impure), and consequently the latter were much colder and more humid, qualities he believed made their flesh toxic.[43]

The academic perception is that natural repugnance from "weird-looking" fish is a significant factor in the origin of the restrictions.[44][45][46][47][48] Vedic India (and presumably the Persians also) exhibit such repugnance, generally allowing fish, but forbidding "weird looking" fish and exclusively carnivorous fish;[23][24][25] in Egypt, another significant and influential culture near to the Israelites, the priests avoided all fish completely.[22]

Birds

[edit]With regard to birds, no general rule is given, instead Leviticus 11:13–19 and Deuteronomy 14:11–18 explicitly list prohibited birds. In the Shulchan Aruch, 3 signs are given to kosher birds: the presence of a crop, an extra finger, and a gizzard that can be peeled. The bird must also not be a bird of prey. The Masoretic Text lists the birds as:

- nesher[49][50]—"that which sheds its feathers"

- peres[49][50]—"bone breaker"

- ozniyah[49][50]—feminine form of oz, meaning "strong"

- ra'ah[51]/da'ah[52]—that which darts, in the sense of "rapid"

- ayyah[51][52]

- orev[53][54]

- bat yaanah[55][56]—daughter of howling

- tahmas[55][56]—one who scratches the face

- shahaf[55][56]—one which atrophies

- netz[55][56]

- kos[57][58]—"cup"

- shalak[57][59]—"plunger"

- yanshuf[57][58]—"twilight"

- tinshemet[58][60]—"blower"/"breather"

- qa'at[59][60]—"vomiting"

- racham[59][60]—"tenderness"/"affection"

- hasidah[61][62]—"devoted"

- anafah[61][62]—"one which sniffs sharply", in the sense of 'anger'

- dukifat[61][62]

- atalef[61][62]

The list in Deuteronomy has an additional bird, the dayyah,[51] which seems to be a combination of 'da'ah' and 'ayyah', and may be a scribal error; the Talmud regards it as a duplication of ayyah.[63] This, and the other terms, are vague and difficult to translate, but there are a few further descriptions, of some of these birds, elsewhere in the Bible:

- The ayyah is mentioned again in the Book of Job, where it is used to describe a bird distinguished by its particularly good sight.[64]

- The bat yaanah is described by the Book of Isaiah as living in desolate places,[65] and the Book of Micah states that it emits a mournful cry.[66]

- The qa'at appears in the Book of Zephaniah, where it is portrayed as nesting on the columns of a ruined city;[67] the Book of Isaiah identifies it as possessing a marshy and desolate kingdom.[68]

The Septuagint versions of the lists are more helpful, as in almost all cases the bird is clearly identifiable:

- aeton[69][70]—eagle

- grypa[69][70]—ossifrage

- haliaetos[69][70]—sea eagle

- gyps[71][72]—vulture

- ictinia[71][72]—kite

- corax[73][74]—raven

- stouthios[75][76]—ostrich

- glaux[75][76]—owl

- laros[75][76]—gull

- hierax[75][77]—hawk

- nycticorax[77][78]—night raven

- cataractes[77][78]—cormorant

- porphyrion[79][80]--swamphen, coot

- cycnos[79][81]—swan

- Ibis[78][81]

- Pelican[79][80]

- charadrios[80][82]—plover

- herodios[81][82]—heron

- epops[77][82]—hoopoe

- nycturia[80][82]—bat

- meleagris[82][83]—guineafowl

Although the first 10 birds identified by the Septuagint seem to fit the descriptions of the Masoretic Text, the ossifrage (Latin for "bone breaker") being a good example, the correspondence is less clear for most of the remaining birds.

It is also obvious that the list in Leviticus, or the list in Deuteronomy, or both, are in a different order in the Septuagint, compared to the Masoretic Text.[a]

Attempting to determine the correspondence is problematic; for example, "pelican" may correspond to qa'at ("vomiting"), in reference to the pelican's characteristic behaviour, but it may also correspond to kos ("cup"), as a reference to the pelican's jaw pouch.

An additional complexity arises from the fact that the porphyrion has not yet been identified, and classical Greek literature merely identifies a number of species that are not the porphyrion, including the peacock, grouse, and robin, and implies that the porphyrion is the cousin of the kingfisher. From these meager clarifications, the porphyrion can only be identified as anything from the lilac-breasted roller, Indian roller, or northern carmine bee-eater, to the flamingo. A likely candidate is the purple swamphen.[according to whom?]

During the Middle Ages, classical descriptions of the hoopoe were mistaken for descriptions of the lapwing, on account of the lapwing's prominent crest, and the hoopoe's rarity in England, resulting in "lapwing" being listed in certain bible translations instead of "hoopoe".

Similarly, the sea eagle has historically been confused with the osprey, and translations have often used the latter bird in place of the former. Because strouthos (ostrich) was also used in Greek for the sparrow, a few translations have placed the sparrow among the list.

In Arabic, the Egyptian vulture is often referred to as rachami,[84] and therefore a number of translations render 'racham' as "gier eagle", the old name for the Egyptian vulture.

Variations arise when translations follow other ancient versions of the Bible, rather than the Septuagint, where they differ. Rather than vulture (gyps), the Vulgate has "milvus", meaning "red kite", which historically has been called the "glede", on account of its gliding flight; similarly, the Syriac Peshitta has "owl" rather than "ibis".

Other variations arise from attempting to base translations primarily on the Masoretic Text; these translations generally interpret some of the more ambiguous birds as being various different kinds of vulture and owl. All of these variations mean that most translations arrive at a list of 20 birds from among the following:

- Bat

- Black kite

- Black vulture

- Cormorant

- Cuckoo

- Desert owl

- Eagle

- Eagle owl

- Egyptian vulture

- Falcon

- Flamingo

- Glede

- Great owl

- Gull

- Hawk

- Heron

- Hoopoe

- Ibis

- Indian roller

- Kingfisher

- Kite

- Lapwing

- Lilac-breasted roller

- Little owl

- Nighthawk

- Night raven

- Northern carmine bee-eater

- Osprey

- Ossifrage

- Ostrich

- Owl

- Peacock

- Pelican

- Plover

- Porphyrion (untranslated)

- Raven

- Red Kite

- Screech owl

- Sea eagle

- Sparrow

- Stork

- Swan

- Vulture

- White owl

Despite being listed among the birds by the Bible, bats are not birds, and are in fact mammals (because the Hebrew Bible distinguishes animals into four general categories—beasts of the land, flying animals, creatures which crawl upon the ground, and animals which dwell in water—not according to modern scientific classification).

Most of the remaining animals on the list are either birds of prey or birds living on water, and the majority of the latter in the list also eat fish or other seafood.

The Septuagint's version of the list comprehensively lists most of the birds of Canaan that fall into these categories. The conclusion of modern scholars is that, generally, ritually unclean birds were those clearly observed to eat other animals.[85]

Although it does regard all birds of prey as being forbidden, the Talmud is uncertain of there being a general rule, and instead gives detailed descriptions of the features that distinguish a bird as being ritually clean.

The Talmud argues that clean birds would have craws, an easily separated 'double-skin', and would eat food by placing it on the ground (rather than holding it on the ground) and tearing it with their bills before eating it;[86][87][88] however, the Talmud also argues that only the birds in the biblical list are actually forbidden—these distinguishing features were only for cases when there was any uncertainty in the bird's identity.[88]

Origin

[edit]The earliest rationalistic explanations of the laws against eating certain birds focused on symbolic interpretations. The first indication of this view can be found in the 1st century BC Letter of Aristeas, which argues that this prohibition is a lesson to teach justice, and is also about not injuring others.[89]

Such allegorical explanations were abandoned by most Jewish and Christian theologians after a few centuries, and later writers instead sought to find medical explanations for the rules; Nachmanides, for example, claimed that the black and thickened blood of birds of prey would cause psychological damage, making people much more inclined to cruelty.[43]

However, other cultures treated the meat of certain carnivorous birds as having medical benefits, the Romans viewing owl meat as being able to ease the pain of insect bites.

Conversely, modern scientific studies have discovered very toxic birds such as the pitohui, which are neither birds of prey nor water birds, and therefore the biblical regulations allow them to be eaten.

Laws against eating any carnivorous birds also existed in Vedic India[23][24][25] and Harran,[19][26] and the Egyptian priests also refused to eat carnivorous birds.[22]

Modern practical considerations

[edit]

Due to the difficulty of identification, religious authorities have restricted consumption to specific birds for which Jews have passed down a tradition of permissibility from generation to generation. Birds for which there has been a tradition of their being kosher include:

As a general principle, scavenging birds such as vultures and birds of prey such as hawks and eagles (which opportunistically eat carrion) are unclean.

The turkey[91] does not have a tradition, but because so many Orthodox Jews have come to eat it and it possesses the simanim (signs) required to render it a kosher bird, an exception is made, but with all other birds a masorah is required.

Songbirds, which are consumed as delicacies in many societies, may be kosher in theory, but are not eaten in kosher homes as there is no tradition of them being eaten as such. Pigeons and doves are known to be kosher[93] based on their permissible status as sacrificial offerings in the Temple of Jerusalem.

The Orthodox Union of America considers neither the peafowl nor the guineafowl to be kosher birds[90] since it has not obtained testimony from experts about the permissibility of either of these birds. In the case of the swans, there is no clear tradition of eating them.[96]

Rabbi Chaim Loike is currently the Orthodox Union's specialist on kosher bird species.[97]

Predator birds

[edit]Unlike with land creatures and fish, the Torah does not give signs for determining kosher birds, and instead gives a list of non-kosher birds.

The Talmud also offers signs for determining whether a bird is kosher or not.

If a bird kills other animals to get its food, eats meat, or is a dangerous bird, then is not kosher, a predatory bird is unfit to eat, raptors like the eagles, hawks, owls and other hunting birds are not kosher, vultures and other carrion-eating birds are not kosher either.[98]

Crows and members of the crow family such as jackdaws, magpies and ravens are not kosher.[citation needed] Storks, kingfishers, penguins and other fish-eating birds are not kosher.[98]

Flying insects

[edit]

Deuteronomy 14:19 specifies that all "flying creeping things" were to be considered ritually unclean[99] and Leviticus 11:20 goes further, describing all flying creeping things as filth, Hebrew sheqets.[100] Leviticus goes on to list four exceptions, which Deuteronomy does not.

All these exceptions are described by the Levitical passages as "going upon all four legs" and as having "legs above their feet" for the purpose of leaping.[101] The identity of the four creatures the Levitical rules list are named in the Masoretic Text using words of uncertain meaning:

- arbeh[102]—the Hebrew word literally means "[one which] increases". The Septuagint calls it a brouchos, referring to a wingless locust, and older English translations render this as grasshopper in most parts of the Bible, but inconsistently translate it as locust in Leviticus.[103]

- In the Book of Nahum, the arbeh is poetically described as camping in hedges in cold days, but flying off into the far distance when the sun arises;[104] for this reason, a number of scholars have suggested that the arbeh must actually be the migratory locust.[16]

- sol'am[102]—the Hebrew term literally means "swallower". The Septuagint calls it an attacos, the meaning of which is currently uncertain. The Talmud describes it as having a long head that is bald in front,[105][106] for which reason a number of English translations call it a bald locust (an ambiguous term); many modern scholars believe that the Acrida (previously called Tryxalis) is meant, as it is distinguished by its very elongated head.

- hargol[102]—the Hebrew term literally means strafer (one that runs to the right or to the left). The Septuagint calls it an ophiomachos, literally meaning "snake fighter"; the Talmud describes it as having a tail.[107] The Talmud also states that it has large eggs, which were turned into amulets.[108] This has historically been translated as beetle, but since the 19th century, cricket has been deemed more likely to fit.

- hagab[102]—the word literally means "hider". The Book of Numbers implies that they were particularly small.[109] The Septuagint calls it an akrida, and it has usually been translated as grasshopper.

The Mishnah argues that the ritually clean locusts could be distinguished as they would all have four feet, jumping with two of them, and have four wings which are of sufficient size to cover the entire locust's body.[110] The Mishnah also goes on to state that any species of locust could only be considered as clean if there was a reliable tradition that it was so.

The only Jewish group that continue to preserve such a tradition are the Jews of Yemen, who use the term "kosher locust" to describe the specific species of locusts they believe to be kosher, all of which are native to the Arabian Peninsula.

Due to the difficulties in establishing the validity of such traditions, later rabbinical authorities forbade contact with all types of locust[111] to ensure that the ritually unclean locusts were avoided.[112]

Small land creatures

[edit]Leviticus 11:42–43 specifies that whatever "goes on its belly, and whatever goes on all fours, or whatever has many feet, any swarming thing that swarms on the ground, you shall not eat, for they are detestable." (Hebrew: sheqets). Before stating this, it singles out eight particular "creeping things" as specifically being ritually unclean in Leviticus 11:29–30.[113]

Like many of the other biblical lists of animals, the exact identity of the creatures in the list is uncertain; medieval philosopher and Rabbi Saadia Gaon, for example, gives a somewhat different explanation for each of the eight "creeping things." The Masoretic Text names them as follows:

- holed[114]—the Talmud describes it as a predatory animal[115] that bores underground.[116][117][118]

- akhbar[114], refers to the jerboa

- tzab[119]—the Talmud describes it as being similar to a salamander[120]

- anaqah[114]—this Hebrew term literally means "groaner", and consequently a number of scholars believe it refers to a gecko, which makes a distinctive croaking sound.

- ko'ah[119]

- leta'ah[119]—the Talmud describes it as being paralyzed by heat but revived with water, and states that its tail moves when cut off[121]

- homet[119]

- tinshemet[119]—this term literally means "blower/breather", and also appears in the list of birds

The Septuagint version of the list does not appear to directly parallel the Masoretic, and is thought to be listed in a different order. It lists the eight as:

- galei—a general term including the weasel, ferret, and the stoat, all of which are predatory animals noticeably attracted to holes in the ground.

- mus—the mouse.

- krokodelos-chersaios—the "land crocodile", which is thought to refer to the monitor lizard, a large lizard of somewhat crocodilian appearance.

- mygale—the shrew.

- chamaileon—the chameleon, which puffs itself up and opens its mouth wide when threatened

- chalabotes—a term derived from chala meaning "rock/claw", and therefore probably the wall lizard[citation needed]

- saura—the lizard in general, possibly here intended to be the skink, since it is the other remaining major group of lizards.

- aspalax—the mole-rat, although some older English translations, not being aware of the mole-rat's existence, have instead translated this as mole.

- The earthworm, the snake, the scorpion, the beetle, the centipede, and all the creatures that crawl on the ground are not kosher.[122][123]

- Worms, snails and most invertebrate animals are not kosher.[124][123]

- All reptiles, all amphibians and insects with the exception of four types of locust are not kosher.[124]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In the Masoretic Text, the lists are nearly the same between Leviticus and Deuteronomy, but in the Septuagint Leviticus is clearly in a different order to Deuteronomy

References

[edit]- ^ Leviticus 11:4

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:7

- ^ Leviticus 11:5

- ^ Proverbs 30:24–26

- ^ Leviticus 11:6

- ^ Leviticus 11:7

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:8

- ^ von Engelhardt, W; Wolter, S; Lawrenz, H; Hemsley, J.A. (1978). "Production of methane in two non-ruminant herbivores". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 60 (3): 309–11. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(78)90254-2.

- ^ Rabbi Natan Sliftkin. "The Camel, the Hare, and the Hyrax". Yashar Books. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:4

- ^ a b c d e f g Deuteronomy 14:5

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, Animals

- ^ a b Amar, Zohar; Bouchnick, Ram; Bar-Oz, Guy (2009). "Identification of Kosher Species of Animals in the Light of Archaeozoological Research". Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv. 132: 33–54.

- ^ "Latin Vulgate Old Testament Bible - Deuteronomy 14". vulgate.org. Retrieved 2025-08-03.

- ^ Isaiah 52:20

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia, animals

- ^ Leviticus 11:27

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c d e Jewish Encyclopedia, Dietary Laws

- ^ Peake's commentary on the Bible

- ^ Saadia Gaon, Kitab al-Amanat Wal-l'tikadat, 117

- ^ a b c Porphyry, De Abstinentia 4:7

- ^ a b c d e "Laws of Apastamba" 1:5, 1:29-39, 2:64

- ^ a b c d e Laws of Vasishta, 14:38-48, 14:74

- ^ a b c d e Laws of Bandhayuna, 1:5, 1:12, 14:184

- ^ a b Daniel Chwolson, Die Szabier und der Szabismus, 2:7

- ^ See "Why mammals with split hooves?" https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/why-mammals-with-split-hooves/

- ^ "thekosherexpress.com". thekosherexpress.com.

- ^ "Is Buffalo Kosher?". Chabad.org.

- ^ Leviticus 11:9

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:9

- ^ Leviticus 11:10

- ^ a b Deuteronomy 14:10

- ^ Bavli Niddah 59a, expounded in Bavli Chullin 66b

- ^ Nachmanides, commentary to Leviticus 11:9

- ^ a b Kosher Fish at kashrut.com. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- ^ OU Kosher.org An Analysis of Kaskeses: Past and Present, June 13, 2013

- ^ Niddah 6:9

- ^ 'Abodah Zarah 39b-40a

- ^ A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice. Isaac Klein. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America. New York and Jerusalem. 1979. p. 305 (in 1992 reprint).

- ^ "Kelp Caviar Receives OU Kosher Certification". OU Kosher Certification. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Caviar Kosher". Ohr Somayach.

- ^ a b Nachmanides, Bi'ur on Leviticus

- ^ Cheyne and Black, Encyclopedia Biblica

- ^ Peake's commentary on the BIble

- ^ W. Robertson Smith, "Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia"

- ^ Jacobs, "Studies in Biblical Archaeology"

- ^ Baentsch, "Exodus and Leviticus"

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:13

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:12

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:13

- ^ a b Leviticus 11:14

- ^ Leviticus 11:15

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:14

- ^ a b c d Leviticus 11:16

- ^ a b c d Deuteronomy 14:15

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:17

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:16

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:17

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:18

- ^ a b c d Leviticus 11:19

- ^ a b c d Deuteronomy 14:18

- ^ Hullin 63b

- ^ Job 28:7

- ^ Isaiah 34:13

- ^ Micah 1:8

- ^ Zephaniah 2:14

- ^ Isaiah 34:11

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:13, LXX

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:12, LXX

- ^ a b Leviticus 11:14, LXX

- ^ a b Deuteronomy 14:13, LXX

- ^ Leviticus 11:15, LXX

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:14, LXX

- ^ a b c d Leviticus 11:16, LXX

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:15, LXX

- ^ a b c d Deuteronomy 14:17, LXX

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:17, LXX

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:18, LXX

- ^ a b c d Deuteronomy 14:18, LXX

- ^ a b c Deuteronomy 14:16, LXX

- ^ a b c d e Leviticus 11:19, LXX

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:19, LXX

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia, Vulture

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia, dietary laws

- ^ Hullin 59a

- ^ Hullin 61a

- ^ a b Hullin 63a

- ^ Letter of Aristeas, 145-154

- ^ a b c d e f g h "OU Position on Certifying Specific Animals and Birds | OUkosher.org". Archived from the original on 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ a b "What Is Kosher? | Kosher Definition | KLBD Kosher Certification". Archived from the original on 2012-07-20.

- ^ a b "How do I know whether a particular bird is kosher or not? - miscellaneous animals/pets mitzvot kosher kosher creatures". www.askmoses.com.

- ^ a b c "Leviticus 1:14 If, instead, one's offering to the LORD is a burnt offering of birds, he is to offer a turtledove or a young pigeon". biblehub.com.

- ^ a b Leviticus 1:14

- ^ 61a-b – Determining the kosher status of birds

- ^ "What is Kosher Food, Kosher Rules, Products, Definition, What Does Kosher Mean". www.koshercertification.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "Bioethics" (PDF). www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ a b "What are kosher animals? - miscellaneous animals/pets mitzvot kosher kosher creatures". www.askmoses.com.

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:19

- ^ Leviticus 11:20

- ^ Leviticus 11:21

- ^ a b c d Leviticus 11:22

- ^ The King James Version for example, translates brouchos/arbeh as grasshopper in the Book of Judges, Book of Job, and Book of Jeremiah, but as locust in Leviticus

- ^ Nahum 3:17

- ^ Hullin 65b

- ^ 'Abodah Zarah 37a

- ^ Hullin 65a

- ^ Shabbat 6:10

- ^ Numbers 13:33

- ^ Hullin 3:8

- ^ Joseph Caro,Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De'ah:85

- ^ "Frequently asked questions". www.star-k.org.

- ^ Leviticus 11:29–30

- ^ a b c Leviticus 11:29

- ^ Hullin 52b

- ^ Baba Kama 80a

- ^ Baba Batra 19b

- ^ Hullin 20b

- ^ a b c d e Leviticus 11:30

- ^ Hullin 127a

- ^ Oholot 1:6

- ^ "OU Life - Everyday Jewish Living". OU Life.

- ^ a b Leviticus 11:41

- ^ a b "Which Animals Are Kosher? - Kosher Animals". www.chabad.org.

Kosher animals

View on GrokipediaGeneral Principles

Biblical Sources

The foundational biblical sources for the laws of kosher animals are the Torah passages in Leviticus 11:1–47 and Deuteronomy 14:3–21, which delineate the categories of clean (tahor) and unclean (tamei) creatures permissible or prohibited for consumption by the Israelites.[5][6] These texts establish the divine commandments regarding animal purity, emphasizing ritual distinctions that extend beyond diet to include avoidance of contact with unclean carcasses.[7] The terms tahor and tamei denote states of ritual purity, where tahor animals are suitable for eating and sacrificial use, while tamei ones impart impurity upon contact or ingestion.[7] These laws were revealed to Moses at Mount Sinai as part of the Torah given to the Jewish people approximately 3,300 years ago, forming a core element of the covenantal obligations.[8] The oral law (halakha), which provides interpretive guidance for applying these written commandments, was simultaneously transmitted from Moses to subsequent generations through teacher-to-disciple and parent-to-child instruction, ensuring their preservation and practical implementation.[9][10] An earlier biblical reference to clean animals appears in Genesis 7:2, where God instructs Noah to take seven pairs of every clean beast and clean bird into the ark, alongside one pair of unclean animals, highlighting a pre-Sinaitic awareness of these categories that is later elaborated in kashrut laws.[11] Deuteronomy 14:4–5 provides a specific list of ten clean mammals as exemplars: the ox, sheep, goat, deer, gazelle, roebuck, wild goat, ibex, antelope, and mountain sheep. These scriptural foundations apply across animal categories, with detailed prohibitions and permissions outlined in the core texts.Rationales and Interpretations

The rationales for kosher dietary laws extend beyond mere biblical commandments, encompassing interpretations that emphasize moral, health, symbolic, and practical dimensions to foster spiritual discipline and societal harmony. Medieval philosopher Maimonides, in his Guide for the Perplexed (3:48), posits that these laws primarily serve to promote physical health by prohibiting unwholesome foods, such as pork, which he describes as excessively moist and loathsome due to the animal's dirty habits, thereby preventing digestive issues and disease. He further argues that the restrictions instill temperance and self-control, training individuals to master their appetites through deliberate choices in consumption, while ancillary rules like the prohibition against cutting limbs from living animals (Leviticus 22:28) explicitly avoid cruelty to creatures.[12] Health-based theories gained traction among later scholars, who linked prohibitions to avoiding disease vectors; for instance, pigs were seen as carriers of parasites like trichinosis in ancient contexts without modern cooking methods, and shellfish as potential sources of toxins from scavenging in impure waters. Although Nachmanides (Ramban) in his commentary on Leviticus 11 critiques purely medicinal explanations as insufficient for divine commandments, emphasizing instead spiritual sanctification, he acknowledges practical benefits in distinguishing pure from impure species, which indirectly supports health considerations in rabbinic discourse. These views align with Maimonides' framework, suggesting the laws safeguarded ancient communities from environmental health risks prevalent in the Near East.[13][12] Symbolic interpretations portray kosher criteria as metaphors for ethical and spiritual ideals, with cud-chewing mammals representing stability and contemplative life—regurgitating and re-chewing food symbolizes ruminating on Torah teachings to internalize wisdom, contrasting the impulsive nature of non-ruminants. Birds of prey and carnivores, prohibited due to their violent predation, embody cruelty and aggression, which consuming them might inculcate in humans; Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, in Chorev (chapter 68), explains that such animals influence the eater toward savagery, while kosher species promote peaceful, domesticated virtues aligned with Jewish values of compassion. These symbols reinforce the laws' role in shaping moral character, distinguishing Israel through mindful separation of holy from profane.[14][15] Ecological factors underscore how the laws adapted to the resource-scarce ancient Near East, where kosher mammals like ruminants with split hooves were ideal for sustainable herding in arid lands, as they efficiently converted marginal vegetation without competing directly with human food sources. Pigs, conversely, required abundant water and shade unsuitable for the Levant's climate, making their prohibition a practical measure to conserve resources and prevent ecological strain in nomadic or semi-nomadic societies. This alignment with regional practices, as evidenced by archaeological patterns showing low pig consumption among Israelites compared to neighbors, highlights the Torah's implicit promotion of environmental stewardship.[16] Rabbinic expansions in the Talmud, particularly tractate Chullin, delve into interpretive nuances, notably why the pig remains an iconic non-kosher symbol despite possessing split hooves—one of the two required signs. The Talmud (Chullin 59a) brands the pig a "fraud" or hypocrite, as it externally displays a kosher trait while internally lacking cud-chewing, serving as a cautionary archetype against superficial piety that masks true impurity. This exegesis, echoed in later commentaries, uses the pig to illustrate deeper ethical lessons on authenticity, reinforcing the laws' pedagogical value in Jewish life.[17]Mammals

Criteria for Permission

The criteria for determining whether a mammal is kosher derive from explicit biblical commandments in Leviticus 11:3 and Deuteronomy 14:6, which permit only those animals that both chew the cud and possess completely split hooves.[3] This dual requirement establishes a rigorous standard, mandating the presence of both physiological and anatomical signs for permissibility, with the absence of either rendering the animal prohibited.[1] The Torah emphasizes this combination to delineate clean from unclean land creatures, applying solely to mammals and excluding other categories like birds or aquatic life.[4] Chewing the cud, known in Hebrew as gerah, involves the regurgitation of partially digested food from the first stomach chamber (rumen) for re-chewing, allowing ruminants to efficiently process fibrous vegetation through multiple digestive stages.[4] This behavioral trait must be observable and consistent, as it signifies the animal's digestive capability aligned with the biblical description.[1] The hoof requirement specifies fully cloven hooves, where the foot is divided symmetrically into two equal toes that both contact the ground, excluding partial or asymmetrical splits that do not meet the complete separation criterion.[1] This anatomical feature ensures the animal's structure conforms precisely to the Torah's mandate, with rabbinic interpretations clarifying that any deviation, such as fused or incomplete division, disqualifies the species.[4] Beyond these biblical signs, rabbinic law imposes the principle of masorah (unbroken tradition), requiring that a mammal belong to a species historically identified as kosher through generations of Jewish observance; novel or unidentified species are deemed prohibited until their status is verified by reliable tradition to avoid uncertainty.[18] This safeguard preserves the integrity of kashrut by limiting consumption to established lineages, as articulated by authorities like the Shach and Chochmat Adam.[18] To confirm kosher status post-slaughter, a trained inspector known as a bodek conducts a thorough bedikah (examination), scrutinizing the internal organs—especially the lungs—for adhesions, lesions, or defects indicative of prior disease that could invalidate the animal.[19] This process, performed by an individual of scholarly integrity and expertise in halakhah, ensures the mammal was healthy at the time of slaughter and free from treifot (prohibitive blemishes), with particular attention to regional health risks or injuries.[19]Examples of Kosher and Non-Kosher Mammals

Common examples of kosher mammals include the cow (Bos taurus), which chews its cud and has fully cloven hooves, making it a staple in Jewish dietary practices worldwide.[1] Similarly, the sheep (Ovis aries) and goat (Capra hircus) meet both criteria and are widely consumed after proper ritual slaughter.[1] The deer family (Cervidae), encompassing species like the roe deer and red deer, also qualifies as kosher due to their split hooves and rumination.[1] Bison (Bison bison) is recognized as kosher by major certification bodies like the Orthodox Union (OU), with its meat processed and available in North American markets.[20][21] Non-kosher mammals illustrate failures to meet one or both criteria. The pig possesses split hooves but does not chew its cud, rendering it treif (forbidden).[1] The camel chews its cud yet has padded feet without true cloven hooves, disqualifying it.[1] Rabbits and hares chew their cud but lack cloven hooves, while horses and donkeys have neither trait.[1] In various regions, additional kosher mammals such as water buffalo, North American buffalo, and antelope species are accepted, provided they exhibit the required signs and are slaughtered according to halachic standards.[21][22] This extends to exotic examples like the giraffe, which meets both criteria despite its rarity in consumption.[2] Elk, another member of the deer family, has gained modern acceptance in North America, with kosher-certified products emerging in the early 21st century.[23][24] Borderline cases among camelids, such as llamas and alpacas, are generally non-kosher; they chew their cud but have non-cloven feet similar to camels.[25] The prohibition on non-kosher mammals also applies to their derivatives, including milk, which is considered non-kosher if sourced from such animals.[26]| Category | Examples | Reason for Status |

|---|---|---|

| Kosher Mammals | Cow (Bos taurus), Sheep (Ovis aries), Goat (Capra hircus), Deer (Cervidae family), Bison (Bison bison), Buffalo, Antelope, Giraffe, Elk | Possess both split hooves and chew cud.[1][20][21][22][2][23] |

| Non-Kosher Mammals | Pig, Camel, Rabbit/Hare, Horse/Donkey, Llama/Alpaca | Lack one or both criteria (e.g., pig has split hooves but no cud; camel has cud but no split hooves).[1][25] |