Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

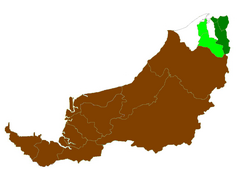

Limbang

View on Wikipedia

Limbang is a border town and the capital of Limbang District in the Limbang Division of northern Sarawak, East Malaysia, on the island of Borneo. This district area is 3,978.10 square kilometres,[2] and population (year 2020 census) was 56,900. It is located on the banks of the Limbang River (Sungai Limbang in Malay), between the two halves of Brunei.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]A settlement along the Limbang River was previously known as "Pangkalan Tarap" where trade activities thrived. The name was derived from a well-known fruit in the Malay community. However, when the settlement was combined with Trusan district and Lawas district, "Pangkalan Tarap" changed its name to "Limbang", naming it after the river on which it is situated.[3]

History

[edit]Bruneian sultanate

[edit]In 1884, there was a rebellion by Limbang residents, protesting against the high tax rate imposed by the Bruneian Empire. William Hood Treacher, who held the dual position as the governor of North Borneo and British royal consul at Labuan, saw an opportunity to acquire more territories from the Bruneian empire. Treacher offered himself to mediate the taxation dispute between the local chiefs and the Bruneian empire. He sailed to Brunei on H.M.S Pegasus, backed by British navy. Treacher successfully arranged for peace in the Limbang region after Temenggong Hashim agreed not to impose any more arbitrary taxes. After the event, Treacher leased Padas River, Klias Peninsula, Bongawan, and Tawaran (now Tuaran) from the sultan of Brunei for $3000 payment per year.[4]

The Brooke government, threatened by Treacher's expansionist policy into northern Sarawak, sent F.O. Maxwell, a Resident of the First Division of Sarawak (today Kuching Division) to Brunei, demanding compensation for the killings of Sarawak subjects in Trusan area (near Lawas). Trusan area at that time was still under the control of the Brunei government. Maxwell also threatened to stop the cession money payment if he did not receive any compensation. Under pressure from Maxwell, Temenggong Hashim agreed to cede the Trusan area to Sarawak. However, the Sultan of Brunei (Sultan Mumin) did not consent to the cession of land. Both Charles Brooke and Temenggong maintained that Sultan's stamp was not required for the cession. Charles later occupied the Trusan area by force.[4] Brunei later agreed to cede Trusan in 1885 and Padas in 1887.[5] On 29 May 1885, Sultan Mumin died and Temenggong Hashim ascended to the Brunei throne to become Sultan Hashim.[4]

In 1886, Leys (former consul of Brunei) and Charles Brooke tried to persuade Sultan Hashim to cede Limbang but to no avail. Sultan Hashim's decision was in line with his pangerans (princes) that further cession of Bruneian territory will leave Sultan's authority in name only. Besides, Sultan Hashim did not wish to see his sultanate vanishing under his rule. Sir Frederick Weld, former governor of the Straits Settlement from 1880 to 1887, went to Labuan in May 1887. Weld then consulted the chiefs of the Limbang River. They firmly rejected Sultan's rule and were willing to accept a white man's rule. Weld tried to push an ultimatum that the Sultan either agreed on the cession of Limbang or to accept a Resident. Sultan Hashim hesitated. Crocker, the acting governor of North Borneo, advised the Sultan that if he did not accept a Resident in Limbang, James Brooke will be permitted to seize Limbang without any compensation to the Sultan. Sultan Hashim decided to accept a Resident after Crocker's advice.[4]

On 17 September 1888, Brunei signed an agreement with Great Britain which formally put Brunei under British protectorate. Sir Rutherford Alcock, managing director of North Borneo Company, Sir Robert Meader, assistant under-secretary of the colonial office, and Sir Federick Weld thought that making Brunei a protectorate will enable the final division of Brunei and stem further losses of Bruneian territories. However, British prime minister Lord Salisbury was eager for Brunei to vanish from the world map before the protectorate agreement was signed. He finally agreed to the protectorate treaty after he was assured by his officials that the protectorate status granted to Brunei will not stop its ultimate absorption into either Sarawak or North Borneo. Acting Consul Hamilton decided to go to Limbang in October 1889 to assess the people's sentiments there. The Limbang chiefs gave the same assertions that they will never submit to Sultan's rule.[4] On 17 March 1890, Rajah Charles Brooke annexed Limbang, subjected to the approval of the British government, claiming that the local chiefs of Limbang had been independent of Brunei's rule for five years and had hoisted a Sarawak flag.[4]

Sultan then sent an envoy to the governor of the Straits, Sir F. Dickson to protest against the Rajah's move of annexing Limbang. Sultan's envoy claimed that the people of Limbang had been paying tribute to Sultan since Weld's visit in May 1887 thus Brunei still have sovereignty over Limbang. Consul Trevenen then went to Limbang, and confirmed that 13 of the 15 chiefs in Limbang said that Sultan had not exercised any control over them for seven years. In August 1892, Sir Cecil Smith, the governor of the Straits Settlements, decided that Sarawak should possess Limbang and would pay a tribute of $6000 to Sultan of Brunei. However, Sultan of Brunei refused to accept the money or suggest his own terms of the cession.[4] In August 1895, the British colonial office considered the case closed despite no agreement being reached between the Sultan and the Brooke government.[4] Between 1899 and 1901, another rebellion occurred in Tutong District and Belait District. Sultan Hashim was again pressured by Charles Brooke and a new British Consul of Borneo Hewette, to cede both the districts, but he firmly refused, as the loss of both districts would make Brunei non-existent on the map of Borneo, resembling "a tree without branches".[5] However, Sultan Hashim persistently protested against the decision to cede Limbang until his death in 1906.[4] Sultan Hashim considered Limbang as a significant resource, supplying Brunei with food, forest produce, timber, and fisheries. Sultan Hashim also thought that "Brunei is Limbang and Limbang is Brunei". Before his death, Sultan Hashim signed a supplementary agreement (after the 1888 protectorate agreement) with the British government in 1906 to accept a Resident in Brunei to ensure the survival of the Brunei kingdom and stem further losses of the Bruneian territories.[5]

Federation of Malaysia

[edit]During the Brunei Revolt in 1962, Limbang was occupied by the North Borneo Liberation Army (Tentera Nasional Kalimantan Utara, TNKU). TNKU killed four members of the police and eleven European civilians including the Limbang district officer and his wife. Within five days, British and Australian forces from Singapore contained the rebellion.[6]

Subsequent Sultans of Brunei made the Limbang claims in 1951, 1963, and 1973.[7] Brunei-Malaysia maritime boundary was also in dispute since 1981 after Malaysia published its maps in 1979. Negotiations of maritime borders started in 1995. In 2003, Malaysia discovered huge oil reserves at Kikeh, off the coast of Sabah and Brunei. This oil reserve represented 21% of Malaysian total oil reserves at that time. Brunei disputed the Malaysian claim on the Kikeh oil reserve. The dispute ended in 2009 when both countries agreed on the final maritime boundaries. Malaysia also agreed that Brunei holds the rights to the Kikeh oil fields.[8] In return, Brunei allowed the establishment of Commercial Arrangement Areas (CAA) where both countries would share the oil and gas revenues from the disputed maritime areas. However, the quantum of revenue sharing was not disclosed. Brunei also agreed in principle that the final demarcation of the Malaysia-Brunei land border will be based upon five agreements signed between 1920 and 1939 while the remaining borders will be decided by using the watershed model of border demarcation. Malaysian Foreign Minister Datuk Seri Dr Rais Yatim said that such principles would essentially allow Limbang to be placed within Malaysian borders.[9][10] However, Brunei Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade II Lim Jock Seng denied that Brunei has dropped the claims on Limbang.[11] As of 2023, final demarcation of land boundaries between Malaysia and Brunei has not yet completed.[12][13]

Geography

[edit]

Climate

[edit]Limbang features an equatorial climate that is a tropical rainforest climate more subject to the Intertropical Convergence Zone than the trade winds and with no or rare cyclones. The climate is warm and wet. The city sees heavy precipitation throughout the course of the year. The Northeast Monsoon blows from December to March, while the Southeast Monsoon dominates from around June to October.

| Climate data for Limbang | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 389 (15.3) |

264 (10.4) |

270 (10.6) |

314 (12.4) |

347 (13.7) |

267 (10.5) |

274 (10.8) |

287 (11.3) |

370 (14.6) |

384 (15.1) |

401 (15.8) |

398 (15.7) |

3,965 (156.2) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[14] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Local government

[edit]Limbang is part of the Limbang District, which is part of the Limbang Division, which is part of Sarawak, Malaysia.

Economy

[edit]Before the late 19th century, Limbang was the "rice bowl" for Brunei, producing cheap agricultural produce for Bruneian Empire.[15] Northern Region Development Agency (NRDA) was established on 15 March 2018.[16] NRDA has been tasked to develop aquaculture, livestock, oil and gas as well as logistics industries in Limbang and Lawas districts to reap economic benefits from Brunei Darussalam–Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA).[17]

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]Limbang is served by Limbang Airport, which also serves the whole of Limbang District.

Road

[edit]Owing to its geographical location, Limbang is completely cut off from the rest of Sarawak's road network. However, it has good road links to both parts of Brunei, located to the east and west of the district. There is also a good local network of roads within the district. As the only road connection to outside the district is through Brunei, one must have a passport to travel into or out of Limbang.

There are two Immigration, Customs and Quarantine Complexes in Limbang district, both into Brunei.[18]

- Tedungan: This checkpoint corresponds to Brunei checkpoint is called Kuala Lurah.[19] It is located 43 km west of Limbang. It is the road crossing into the main part of Brunei from Limbang.

- Pandaruan: This checkpoint enters Kampung Ujong Jalan, Temburong district, Brunei over the Pandaruan River,[20] located at 15 km east of Limbang.[citation needed] Previously, the crossing was only possible by using ferry services. Pandaruan Bridge was built on 8 December 2013 to facilitate river crossings.[20]

-

Malaysian passport exit stamp from Tedungan ICQS Checkpoint.

-

Entry stamp from Pandaruan ICQS Checkpoint.

-

Entry stamp from the Limbang Wharf ICQS Checkpoint, for boat arrivals from Brunei and Labuan.

Other utilities

[edit]Education

[edit]- SJK (C) Chung Hwa Limbang

- SJK (C) Yuk Hin

- SK Limbang

- SK Melayu Pusat

- SK Kampung Pahlawan

- SK St. Edmund

- SK Menuang

- SK Batu Danau

- SK Pengkalan Jawa

- SK Tedungan

- SK Bukit Luba

- SK Tanjong

- SK Meritam

- SK Ukong

- SK Nanga Medamit

- SK Long Napir

- SK Kuala Mendalam

- SK Nanga Merit

- SK Kubong

- SK RC Kubong

- SK Gadong

- SMK Seri Patiambun Limbang

- SMK Medamit

- SMK Limbang

- SMK Kubong

- SMK(A) Limbang

Healthcare

[edit]The old Limbang Hospital is located in Limbang which is now used as a Laboratory of Drugs and Drug Stores. It was established on 18 August 1961 with 16 nurses and 10 attendants with 54 beds.

In line with the increase in population and the development of Limbang Town, the new Limbang Hospital was officially opened on June 29, 1980, by the then-President of the State of Sarawak Tun Datuk Patinggi Abang Hj MuhammadSalahuddin. The construction cost RM 4.912 million with an area of 7.8 hectares.

As of 2017, a staff strength of 279 people including 19 Medical Officers and 1 Gynecologist and 2 Radiologists.

As of 2023, it now has 2 Physicians, 1 General Surgeon, 1 Anaesthesiologist, 1 Obgyn specialist, 2 radiologists, 1 pediatrician, and 1 psychiatrist offering specialist services. It is equipped with CT Scan, ICU, Operating Theater and an Endoscopy Room.

Culture and leisure

[edit]Limbang Regional Museum

[edit]

The Limbang Regional Museum is located in a fort built by Rajah Charles Brooke in 1897. It is located in the area annexed to Sarawak by the White Rajah in 1890.

Taman Tasik Bukit Mas

[edit]Taman Tasik Bukit Mas (literal translation: Gold Hill Lake Park) is a recreational park set in Limbang's iconic feature, Bukit Mas. Limbang residents do their recreational activities in the park in the evening. A children's playground, lake, barbecue site, suspension bridge and toilet are provided.

Limbang Plaza

[edit]Limbang Plaza is located in the town centre, and is often dubbed the definite centre of Limbang. This building mainly consists of three components: Purnama Hotel, a shopping mall and various government offices (located atop the mall). It's also used for other businesses and activities.

Currently the mall has about 50 shopping outlets, with a local supermarket chain, Queen, as the main tenant.

Pasar Tamu

[edit]"Pasar Tamu" is a local gathering where villagers come to the town of Limbang to sell their goods. Usually it is held every Friday, but preparations begin on Thursday.

The market has attracted not only local residents, but also Bruneians.

Notable people

[edit]- Abang Abdul Rahman Zohari Abang Openg - 6th and current Premier of Sarawak.

- James Wong (politician) - the former Deputy Chief Minister of Sarawak.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Official Portal of the Sarawak Government". sarawak.gov.my. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Portal Rasmi Pentadbiran Bahagian Limbang". limbang.sarawak.gov.my. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Info Daerah Limbang (Limbang district information)". Limbang Divisional Office. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018. Alt URL

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Crisswell, CN (September 1971). "The Origins of the Limbang Claim". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2 (2): 218–229. doi:10.1017/S0022463400018622. JSTOR 20069920. S2CID 159643270. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Ismail, Haji Awang Nordin. "Perjanjian 1888: Suatu Harapan dan Kekecewaan (The 1888 agreement: a hope and also a disappointment)" (PDF). Jabatan Sejarah, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Francis, Richard (March 2003). "The Raid on Limbang – 1962". Naval Historical Society of Australia. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "Brunei and Sarawak border issue records" (PDF). Sarawak state library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Maharup, Khairun Syazwan; Ayob, Azman; Chandran, Suseela Devi; Mahamad Aziz, Farhatul Mustamirrah (2021). "The bickering brethren: Malaysia-Brunei Territorial Disputes 2003-2009 and Their Resolutions" (PDF). 8th International Conference on Public Policy and Social Science: 413–417.

- ^ Shen Li, Leong (16 March 2009). "Brunei drops claim over Limbang in Sarawak (Update3)". The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Hamdan, Nurbaiti (20 March 2009). "Limbang border to be set". The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Othman, Azlan (18 March 2009). "Brunei denies Limbang story". Sultanate.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ Chan, Dawn (5 April 2021). "'Expedite works on demarcation, survey of land that borders Malaysia and Brunei'". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "PM Anwar to bring up Sarawak's proposals for bilateral coorperation with Brunei Sultan tomorrow". Dayak Daily. 23 January 2023. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Climate: Limbang". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Clearly, Mark; Shaw, Brian (April 1992). "Limbang: a lost province of oil-rich Brunei Darussalam". Geography. 77 (2). Taylor & Francis: 178–181.

- ^ Veno, Jeremy. "Three agencies under Recoda established, Score expected to generate RM334 bln". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 30 May 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Limbang-Lawas Growth Area". RECODA. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Immigration extends operation hours along Sarawak-Sabah border". The Borneo Post. 29 January 2016. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "JPJ to station officers at Bakelalan-Indonesian border checkpoint". Dayak Daily. 25 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Friendship Bridge a symbol of close M'sia-Brunei ties". The Borneo Post. 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

External links

[edit]Limbang

View on GrokipediaLimbang is a border town serving as the capital of Limbang District in the Limbang Division of northern Sarawak, Malaysia, located on the island of Borneo along the banks of the Limbang River.[1][2]

Its peculiar geography places it between two Bruneian enclaves, isolating it from the rest of Sarawak by land and requiring travelers to pass through Brunei or use air and water routes for domestic Malaysian connectivity.[1]

The district covers 3,978 square kilometers and had a population of 45,061 according to the 2020 census.[2]

Historically, Limbang formed part of the Brunei Sultanate until its annexation by Charles Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak, in 1890, a move that involuntarily severed Brunei's territory into non-contiguous sections and supplied Sarawak with valuable resources including food, timber, and fisheries.[1][3][4]

Today, Limbang functions as a transit hub with multiple border checkpoints to Brunei, supports diverse ethnic communities, and provides access to natural sites such as the Merarap Hot Springs and Kelabit Highlands.[1]