Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

London Stone

View on Wikipedia

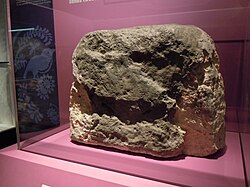

London Stone is a historic landmark housed at 111 Cannon Street in the City of London.[1] It is an irregular block of oolitic limestone measuring 53 × 43 × 30 cm (21 × 17 × 12"), the remnant of a once much larger object that had stood for many centuries on the south side of the street.

The name "London Stone" was first recorded around the year 1100. The date and original purpose of the stone are unknown, although it is possibly of Roman origin. There has been interest and speculation about it since the medieval period, but modern claims that it was formerly an object of veneration, or has some occult significance, are unsubstantiated.

Description

[edit]The present London Stone is only the upper portion of a once much larger object. The surviving portion is a block of oolitic limestone approximately 53 cm wide, 43 cm high, and 30 cm front to back (21 × 17 × 12 inches).[2] A study in the 1960s indicated that the stone is Clipsham limestone, a good-quality stone from Rutland transported to London for building purposes in both the Roman and medieval periods.[3] More recently, Kevin Hayward has suggested that it may be Bath stone, the stone most used for monuments and sculpture in early Roman London and in Saxon times.[4]

The stone is located on the north side of Cannon Street, opposite Cannon Street station, in an aperture in the wall of 111 Cannon Street (EC4N 5AR), within a Portland stone casing.

History

[edit]

When London Stone was erected and what its original function was are unknown, although there has been much speculation.

The stone was originally located on the south side of medieval Candlewick Street (afterward widened to create modern Cannon Street), opposite the west end of St Swithin's Church. It is shown in this position on the Copperplate map of London, dating to the 1550s,[5] and also appears on the derivative "Woodcut" map of the 1560s. It was described by the London historian John Stow in his Survey of London (1598) as "a great stone called London stone", "pitched upright ... fixed in the ground verie deep, fastened with bars of iron".[6]

Stow does not give the dimensions of this "great stone", but a French visitor to London in 1578 had recorded that the stone was three feet high (above ground), two feet wide, and one foot thick (90 × 60 × 30 cm).[7] Thus, although it was a local landmark, the part of it standing above ground was not particularly large.

Middle Ages

[edit]The earliest reference to the stone is usually said to be that in a medieval document cited by Stow in 1598. He refers to an early list of properties in London belonging to Christ Church, Canterbury (Canterbury Cathedral), and says that one piece of land was described as lying "neare unto London stone".[6] Stow claims that the list had been bound into the end of a Gospel Book given to the cathedral by "Ethelstane king of the west Saxons", usually identified as Æthelstan, king of England (924–939). However, it is impossible to confirm Stow's account, since the document he saw cannot now be identified with certainty. Nevertheless, the earliest extant list of Canterbury's London properties, which has been dated to between 1098 and 1108, does refer to a property given to the cathedral by a man named "Eadwaker æt lundene stane" ("Eadwaker at London Stone").[8] Although not bound into a Gospel Book (it is now bound into a volume of miscellaneous medieval texts with a Canterbury provenance (MS Cotton Faustina B. vi) in the British Library), it could be that it was this, or a similar text, that Stow saw.[9]

Like Eadwaker, other medieval Londoners acquired or adopted the byname "at London Stone" or "of London Stone" because they lived nearby. One of these was "Ailwin of London Stone", the father of Henry Fitz-Ailwin de Londonestone, the first Mayor of the City of London, who took office some time between 1189 and 1193, and governed the city until his death in 1212. The Fitz-Ailwin house stood away from Candlewick Street, on the north side of St Swithin's church.[9]

London Stone was a well-known landmark in medieval London, and when in 1450 Jack Cade, leader of a rebellion against the corrupt government of Henry VI, entered the city with his men, he struck his sword on London Stone and claimed to be "Lord of this city".[10] Contemporary accounts give no clue as to Cade's motivation, or how his followers or the Londoners would have interpreted his action. There is nothing to suggest he was carrying out a traditional ceremony or custom.

16th and 17th centuries

[edit]By the time of Queen Elizabeth I London Stone was not merely a landmark, shown and named on maps, but a visitor attraction in its own right. Tourists may have been told variously that it had stood there since before the city existed, or that it had been set up by order of King Lud, legendary rebuilder of London, or that it marked the centre of the city, or that it was "set [up] for the tendering and making of payment by debtors".[6][7][11]

It appears to have been routinely used in this period as a location for the posting and promulgation of a variety of bills, notices, and advertisements.[12] In 1608 it was listed in a poem by Samuel Rowlands as one of the "sights" of London (perhaps the first time the word was used in that sense) shown to "an honest Country foole" on a visit to town.[13][14]

During the 17th century the stone continued be used as an "address", to identify a locality. Thus, for example, Thomas Heywood's biography of Queen Elizabeth I, Englands Elizabeth (1631), was, according to its title page, "printed by Iohn Beale, for Phillip Waterhouse; and are to be sold at his shop at St Pauls Head, neere London stone"; and the English Short Title Catalogue lists over 30 books published between 1629 and the 1670s with similar references to London Stone in the imprint.[15]

In 1671 the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers broke up a batch of substandard spectacles on London Stone:

Two and twenty dozen [= 264] of English spectacles, all very badd both in the glasse and frames not fitt to be put on sale ... were found badd and deceitful and by judgement of the Court condemned to be broken, defaced and spoyled both glasse and frame the which judgement was executed accordingly in Canning [Cannon] Street on the remayning parte of London Stone where the same were with a hammer broken in all pieces.[16][17]

The reference to "the remayning parte of London Stone" may suggest that it had been damaged and reduced in size, perhaps in the Great Fire of London five years earlier, which had destroyed St Swithin's church and the neighbouring buildings; it was later covered with a small stone cupola to protect it.[18]

18th century to early 20th century

[edit]

In 1598 John Stow had commented that "if carts do run against it through negligence, the wheels be broken, and the stone itself unshaken",[6] and by 1742 it was considered an obstruction to traffic. The remaining part of the stone was then moved, with its protective cupola, from the south side of the street to the north side, where it was first set beside the door of St Swithin's Church, which had been rebuilt by Christopher Wren after its destruction in the Great Fire. It was moved again in 1798 to the east end of the church's south wall, and finally in the 1820s set in an alcove in the centre of the wall within a solidly built stone frame set on a plinth, with a circular aperture through which the stone itself could be seen. In 1869 the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society arranged for the installation of a protective iron grille and an explanatory inscription in Latin and English on the church wall above it.[19]

During the 19th and 20th centuries the London Stone was regularly referred to in popular London histories and guidebooks, and visited by tourists; during his stay in England in the 1850s the American author Nathaniel Hawthorne recorded a visit to London Stone in his journal, noting the indentations on the top "which are said to have been made by Jack Cade's sword".[20] In 1937 Arthur Mee, the founder of The Children's Newspaper and author of The King's England series of guidebooks, described it as "a fragment of its old self [...] said by some to have been a stone set up in Stone Age days".[21]

The archaeologist George Byron Gordon was more expansive (and fanciful) in the course of his Rambles in Old London, published in 1924. He described London Stone as "the very oldest object in London streets" and "an object of great antiquity when the Romans arrived and their predecessors the ancient Britons found it on their arrival more than two thousand years before. It was erected by the people of the New Stone Age".[22]

1940 to present

[edit]

In 1940 St Swithin's church was burnt out by bombing in the Blitz. However, the outer walls remained standing for many years, with London Stone still in its place in the south wall. In 1962 the remains of the church were demolished, and replaced by an office building, 111 Cannon Street, which originally housed the Bank of China; London Stone was placed without ceremony in a specially constructed Portland stone alcove, glazed and guarded with an iron grille, in the new building.[4] Inside the building it was protected by a glass case. The stone and its surround, including the iron grille, were designated a Grade II* listed structure on 5 June 1972.[1]

In the early 21st century the office building was scheduled for redevelopment, and in October 2011 the then landowners proposed to move the stone to a new location further to the west. Objections were raised by, among others, the Victorian Society and English Heritage, and the proposal was rejected by the City of London Corporation.[23][24]

Until February 2016 the ground floor of the building was occupied by a branch of WHSmith newsagents.[25] Inside the shop London Stone in its glass case was hidden behind a magazine rack and not usually accessible. In March 2016, planning permission was granted to allow the building to be demolished and replaced by a new one. The stone was put on temporary display at the Museum of London while the building works were carried out.[26][27][28] It was returned to Cannon Street in October 2018. The new premises publicly display London Stone on a plinth, within a Portland stone casing loosely inspired by its 19th–century predecessor, and behind glass. The plaque adjacent to the stone reads

London StoneThe remaining part of London Stone, which once stood in the middle of Cannon Street, slightly west of its present location. Its original purpose is unknown, although it may be Roman and related to Roman buildings that lay to the south. It was already called 'London Stone' in the 12th century and became an important city landmark. In 1450 Jack Cade, leader of the rebellion against the corrupt government of Henry VI, struck it with his sword and claimed to be Lord of London.

In 1742, London Stone was moved to the north side of the street and eventually set in an alcove in the wall of St Swithin's church on this site.

The church was bombed in the Second World War and demolished in 1961–1962, and London Stone was incorporated into a new office building on the site. Following redevelopment it was placed in its present location in 2018.

Interpretations

[edit]14th century

[edit]The Short English Metrical Chronicle, an anonymous history of England in verse composed in about the 1330s, which survives in several variant recensions (including one in the so-called Auchinleck manuscript), includes the statement that "Brut sett Londen ston" – that is to say, that Brutus of Troy, the legendary founder of London, set up London Stone.[29][30] This claim suggests that interest in the stone's origin and significance already existed. However, the story does not seem to have circulated widely elsewhere, and was not repeated in other chronicles.

16th century

[edit]In 1598 the London historian John Stow admitted that "The cause why this stone was set there, the time when, or other memory hereof, is none".[6] However, his contemporary William Camden, in his Britannia of 1586, concluded that it was a Roman milliarium, a central stone from which all distances in Roman Britain were measured, and similar to the Milliarium Aureum of Rome.[31] This identification remains popular, although there is no archaeological evidence to support it.[32]

18th century

[edit]Alternatively, writers in the 18th century speculated that the stone was prehistoric and had been an object of Druidic worship.[33] Although this suggestion is now generally dismissed, it was revived in 1914 by Elizabeth Gordon in an unorthodox book on the archaeology of prehistoric London. She envisaged London Stone as an ancient British "index stone" pointing to a great Druidic stone circle, similar to Stonehenge, and claimed it had once stood on the site of St Paul's.[34] As noted above, in 1924 American archaeologist George Byron Gordon claimed a "New Stone Age" date for it, but such claims do not find favour with modern archaeologists, since there is no evidence.[32]

19th century

[edit]By the early 19th century, a number of writers had suggested that London Stone was once regarded as London's "Palladium", a talismanic monument in which, like the original Palladium of Troy, the city's safety and wellbeing were embodied.[35] This view seemed to be confirmed when a pseudonymous contributor to the journal Notes and Queries in 1862 quoted a supposedly ancient proverb about London Stone to the effect that "So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe, so long shall London flourish".[36]

This verse, if it were genuine, would link London Stone to Brutus of Troy, as well as confirming its role as a Palladium. However, the writer in Notes and Queries was identified as Richard Williams Morgan, an eccentric Welsh clergyman. In an earlier book, Morgan had claimed that the legendary Brutus was a historical figure; London Stone, he wrote, had been the plinth on which the original Trojan Palladium had stood, and was brought to Britain by Brutus and set up as the altar stone of the Temple of Diana in his new capital city of Trinovantum or "New Troy" (i.e. London).[37] This story, and the verse about the "Stone of Brutus", can be found nowhere any earlier than in Morgan's writings, and both are probably his own invention. Although London Stone had been associated with Brutus in the 14th century, that tradition had never reached print, and there is nothing to indicate that Morgan had encountered it.[38] The spurious verse is still frequently quoted, but there is no evidence that London's safety has ever traditionally been linked to that of London Stone.[39]

In 1881 Henry Charles Coote argued that London Stone's name and reputation arose simply because it was the last remaining fragment of the house of Henry Fitz-Ailwin of London Stone (c. 1135–1212), London's first Mayor, although London Stone was mentioned about 100 years before Henry's time, and the Fitz-Ailwin house was some distance from the stone on the other side of St Swithin's church.[40][41]

In 1890 the folklorist and London historian George Laurence Gomme proposed that London Stone was the city's original "fetish stone", erected when the first prehistoric settlement was founded on the site and treated as sacred ever after.[42] Later, folklorist Lewis Spence combined this theory with Morgan's story of the "Stone of Brutus" to speculate about the pre-Roman origins of London in a 1937 book.[43][44]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

By the 1960s, archaeologists had noted that in its original location London Stone would have been aligned on the centre of a large Roman building, probably an administrative building, now known to have lain in the area of Cannon Street station. This has been tentatively identified as a praetorium, even the local "governor's palace". It has further been suggested – originally by the archaeologist Peter Marsden, who excavated there from 1961–1972 – that the stone may have formed part of its main entrance or gate.[45][46] This "praetorium gate theory", while impossible to prove, is the prevailing one among modern experts.[47]

London Stone has been identified as a "mark-stone" on several ley lines passing through central London.[48][49] It has also entered the psychogeographical writings of Iain Sinclair as an essential element in London's "sacred geometry".[50][26]

There are two recent additions to the mythology surrounding London Stone. The first claims that John Dee – astrologer, occultist and adviser to Queen Elizabeth I – "was fascinated by the supposed powers of the London Stone and lived close to it for a while" and may have chipped pieces off it for alchemical experiments; the second that a legend identifies it as the stone from which King Arthur pulled the sword to reveal that he was rightful king. Both these "legends" seem first to be recorded in 2002.[51][citation needed] The first may have been inspired by the fictionalised John Dee of Peter Ackroyd's 1993 novel The House of Doctor Dee (see In literature below).

In literature

[edit]15th to 19th centuries

[edit]

So familiar was London Stone to Londoners that from an early date it features in London literature and in stories set in London. Thus, in an often reprinted anonymous satirical poem of the early 15th century, "London Lickpenny" (sometimes attributed to John Lydgate), the protagonist, lost and bewildered, passes London Stone during his wanderings through the city streets:

Then went I forth by London Stone

Thrwgheout all Canywike Strete ...[52]

In about 1522 a pamphlet was published by the London printer Wynkyn de Worde.[53] It comprised two anonymous humorous poems, the second of which, The Maryage ..., just two pages in length, purports to be an invitation to the forthcoming wedding between London Stone and the "Bosse of Billingsgate", a water fountain near Billingsgate erected or renovated in the 1420s under the terms of the will of the mayor Richard Whittington.[54] Guests are invited to watch the couple dancing – "It wolde do you good to see them daunce and playe." The text, however, goes on to suggest that both London Stone and the Bosse were known for their steadfastness and reliability.

London Stone also features in a tract The Returne of the renowned Caualiero Pasquill of England ... published in 1589.[55][12] Otherwise known as Pasquill and Marforius it was one of three that were printed under the pseudonym of the Cavaliero Pasquill, and contributed to the Marprelate controversy, a war of words between the Church of England establishment and its critics. At the end of this short work, Pasquill declares his intention of posting a notice on London Stone, inviting all critics of his opponent, the similarly pseudonymous Martin Marprelate, to write out their complaints and stick them up on the stone. Some writers have argued that this fictional episode proves that London Stone was a traditional place for making official proclamations.[43][56]

The Jack Cade episode was dramatised in William Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2 (act 4, scene 6), first performed c. 1591–2. In Shakespeare's elaborated version of the event, Cade strikes London Stone with a staff rather than a sword, then seats himself upon the stone as if on a throne, to issue decrees and dispense rough justice to a follower who displeases him.[57]

In 1598, London Stone was again brought to the stage, in William Haughton's comedy Englishmen for My Money, when three foreigners, being led about on stage through the supposedly pitch-black night-time streets of London, blunder into it.[58]

Later, London Stone was to play an important but not always consistent role in the visionary writings of William Blake. Thus in Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, his long illustrated poem on engraved plates begun in 1804, London Stone is a Druidic altar, the site of bloody sacrifices. Alternatively in Jerusalem and in Milton a Poem it is the geographic centre of Golgonooza, Blake's mystical city of London; it is a place where justice is delivered, where Los sits to hear the voice of Jerusalem, and where Reuben sleeps.[59]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]Ray Nelson's science fiction novel Blake's Progress (1975), based on the writings of William Blake, featured an alternative history in which Cleopatra won the Battle of Actium and an Alexandrian Empire replaced the Roman Empire. In the alternate London, called Gogonooza, the London Stone is present, standing in front of a Temple of Isis.

In the last years of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st, the stone has made an increasing number of appearances in novels of imagination and urban fantasy.

- In Peter Ackroyd's novel The House of Doctor Dee (1993), the character Dr. Dee, vaguely based upon the historical figure of the occultist John Dee, claims that London Stone is the last remnant above ground of a glorious antediluvian and now buried city of London that he is searching for.

- London Stone appears as an embodiment of evil in Charlie Fletcher's trilogy for children Stoneheart (2006–2008).

- It features in The Midnight Mayor (2010), Kate Griffin's second Matthew Swift novel about urban magic in London

- It is also part of China Miéville's Kraken (2010),[26] in which it is the beating heart of London and the sports shop that (at the time Miéville was writing) housed it hides the headquarters of the "Londonmancers" who may know the whereabouts of the kraken stolen from the Natural History Museum.

- The third of a series of fantasy novels for children The Nowhere Chronicles by Sarah Pinborough, writing as Sarah Silverwood, is entitled The London Stone (2012): "The London Stone has been stolen and the Dark King rules the Nowhere ..."

- In Marie Brennan's Onyx Court series (2008–2011), the stone is part of the magical bond between the mortal Prince of the Stone and the fairie court beneath London.

- The stone appears in several chapters of Edward Rutherfurd's novel, London (1997). In the second chapter we see it as the marker stone for all the roads in Roman Londinium, and also sitting beside the wall of the Governor's Palace as mentioned above as a hypothesis of its use or origin. It is seen again in the ninth chapter where the main family unit of the novel bring in the character of the foundling who is found propped up against it. It is one of the many central focus points in the novel that the author uses to tie the different time periods together.

- The stone is a central focus of DC Comics Vertigo storyline called The Knowledge (2008), featuring John Constantine's sidekick Chas Chandler.[60]

- The stone also appears many times in the Dark Fae FBI series (2017), by C.N. Crawford and Alex Rivers, in which it is the site of many ancient sacrifices and is used to channel memories and power.

- The stone is mentioned in Nicci French's crime novel Tuesday's Gone (2013).

- The stone and its surrounding area is mentioned in Jodi Taylor's short story Christmas Pie (2023).

See also

[edit]- For the London Stone at Staines, and other Thames riverside boundary markers, see London Stone (riparian).

- For the "Brutus Stone" in Totnes, Devon, see Totnes.

- List of individual rocks

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Historic England. "'London Stone' with stone surround and iron grille set into base of number 111 Cannon Street EC4 (Grade II*) (1286846)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Clark 2007, p. 169.

- ^ Merrifield, Ralph (1965). The Roman City of London. London: Benn. pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Clark 2007, p. 177.

- ^ Clark 2007, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b c d e Stow, John (1908). Kingsford, C. L. (ed.). A Survey of London. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b Grenade, L. (2014) [1578]. Keene, Derek; Archer, Ian (eds.). Les singularitez de Londres, noble, fameuse cité, capital du Royaume d'Angleterre: Ses antiquitez et premiers fondateurs [The Singularities of London, 1578 ] (in French and English). Vol. 175. London: London Topographical Society. pp. 103–104, 224. ISBN 978-0-902087-620.

- ^ Kissan, B. W. (1940). "An early list of London properties". Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. new series. 8 (2): 57–69.

- ^ a b Clark 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Clark 2007, pp. 179–186.

- ^ Groos, G.W. (1981). The Diary of Baron Waldstein: A Traveller in Elizabethan England. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Clark 2015.

- ^ Rowlands, Samuel (1608). "A straunge sighted Traveller". Humors Looking Glasse. London: William Ferebrand. sig. D3 recto.

- ^ Rowlands, Samuel (1872) [1608]. "A straunge sighted Traveller". Humors Looking Glasse. Hunterian Club. Vol. 2. Glasgow: Hunterian Club. p. 29.

- ^ "English Short Title Catalogue". London: British Library. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ "Company History". Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Law, Frank W. (1977). The Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers: A History. London: Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers. p. 11.

- ^ Clark 2007, p. 173.

- ^ Clark 2007, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Hawthorne, Nathaniel (1941). Stewart, Randall (ed.). The English Notebooks: Based upon the original manuscripts in the Pierpont Morgan Library. New York / London: Modern Languages Association of America, Oxford University Press. p. 289.

- ^ Mee, Arthur (1937). London: Heart of the Empire and Wonder of the World. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 281.

- ^ Gordon, G. B. (1924). Rambles in Old London. London: John Lane. pp. 45–47.

- ^ City of London planning case file: Relocation of London Stone (Report). London: City of London. 20 October 2011. 11/00664/LBC. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013 – via planning.cityoflondon.gov.uk.

- ^ "Objectors say Minerva unwise to move 'London Stone'". The Times. No. 70477. London. 24 January 2012. p. 16.

- ^ "Directory". All in London. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Higgins, Charlotte (12 March 2016). "Psychogeographers' landmark London Stone goes on show at last". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Neilan, Catherine (10 May 2016). "Mythic London Stone is going on show at Museum of London as current home on Cannon Street is demolished". City AM. London. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Joyful things for Friday – the perambulating London Stone". Histories of Archaeology Research Network. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Clark 2018.

- ^ Burnley, David; Wiggins, Alison, eds. (2003). "The Auchinleck Manuscript: The anonymous short English metrical chronicle". Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland. line 457. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Camden, William (1607). Britannia (in Latin). London: G. Bishop & J. Norton. p. 304.

- ^ a b Clark 2007, p. 178.

- ^ Clark 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Gordon, E.O. (1914). Prehistoric London: Its Mounds and Circles. London: Elliot Stock. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Clark 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Mor Merrion (1862). "Stonehenge". Notes and Queries. 3rd series. 1: 3.

- ^ Morgan, R. W. (1857). The British Kymry or Britons of Cambria. Ruthin: Isaac Clarke. pp. 26–32.

- ^ Clark 2018, p. 178.

- ^ Clark 2010, pp. 45–52.

- ^ Coote, H. C. (1881). "London botes: A lost charter; the traditions of London Stone". Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 5: 282–292.

- ^ Clark 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Gomme, George Laurence (1890). The Village Community: With Special Reference to the Origin and Form of its Survivals in Britain. London: Walter Scott. pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b Spence, Lewis (1937). Legendary London: Early London in Tradition and History. London: Robert Hale. pp. 167–172.

- ^ Clark 2010, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Marsden, Peter (1975). "The excavation of a Roman palace site in London, 1961–1972". Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 26: 1–102, esp. 63–64.

- ^ "Londinium Today: London Stone". Collections research. Museum of London. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Webb, Simon (2011). Life in Roman London. The History Press. pp. 142, 144, 154–155.

- ^ Clark 2010, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Street, Christopher E. (2010). London's Ley Lines: Pathways of Enlightenment. London: Earthstars Publishing. pp. 183–189. ISBN 9780951596746.

- ^ Sinclair, Iain (1997). Lights Out for the Territory. London: Granta. p. 116. ISBN 1862070091.

- ^ "The London Stone". h2g2. c. 2002. Archived from the original on 18 August 2004. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Dean, James M., ed. (1996). "London Lickpenny". Medieval English Political Writings. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications / Western Michigan University. pp. 222–225, esp. 224, lines 81–82. ISBN 1879288648.

- ^ Halliwell, J. O., ed. (1860). A Treatyse of a Galaunt, with the Maryage of the Fayre Pusell the Bosse of Byllyngesgate unto London Stone. London: Printed for the Editor.

- ^ Stow, John (1908). Kingsford, C. L. (ed.). A Survey of London. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 208.

- ^ Nashe, Thomas (1958). McKerrow, Ronald B. (ed.). The Works of Thomas Nashe. Vol. 1 (reprinted ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 65–103.

- ^ "London Stone". Chambers's Journal. 5th series (225): 231–232. 21 April 1888.

- ^ Clark 2007, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Stock, Angela (2004). "Stow's Survey and the London playwrights". In Gadd, Ian; Gillespie, Alexandra (eds.). John Stow (1525–1605) and the Making of the English Past. London: British Library. pp. 89–98, esp. 95. ISBN 0712348646.

- ^ Clark 2010, pp. 43–45.

- ^ "The Knowledge". Vertigo Comics. No. #1–5. DC Comics. 2008.

References

[edit]- Clark, John (2007). "Jack Cade at London Stone" (PDF). Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 58: 169–189 – via lamas.org.uk.

- Clark, John (2010). "London Stone: Stone of Brutus or fetish stone – making the myth". Folklore. 121: 38–60. doi:10.1080/00155870903482007. S2CID 162476008.

- Clark, John (2015). "Pasquill's protestation: Religious controversy at London Stone in the 16th century" (PDF). Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 66: 283–288 – via lamas.org.uk.

- Clark, John (2018). "'Brut sett London Stone': London and London Stone in a 14th century English Metrical Chronicle". Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 69: 171–180.

External links

[edit]- "London Stone" (web main).

- Clark, John. "London Stone" (PDF). Vintry and Dowgate Wards Club. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Clark, John (11 January 2017). London Stone: History and Myth (Report). Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "London Stone". The Modern Antiquarian (themodernantiquarian.com). Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Jenstad, Janelle (2010). "London Stone". The map of early modern London. University of Victoria. Retrieved 27 April 2013. — Article on London Stone linked to a reproduction of the "Woodcut" map of London, c. 1562.

- Coughlan, Sean (22 May 2006). "London's heart of stone". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 24 April 2013. — report on plans to move London Stone in 2006.

London Stone

View on GrokipediaLondon Stone is an irregular block of oolitic limestone, measuring approximately 53 × 43 × 30 centimetres, housed in a protective glass enclosure at 111 Cannon Street in the City of London.[1][2]

First recorded around 1100 CE and referenced in medieval documents as "Lundene Stane," it served as a tangible landmark for public proclamations, oaths, and administrative notices in the vicinity of what was once Candlewick Street (now Cannon Street).[2][1]

Its position near the site of a Roman governor's palace suggests possible ties to Roman-era structures, though no direct archaeological evidence confirms specific functions like a milestone or ceremonial altar.[2]

Geological tests conducted in 2016 by the Museum of London Archaeology indicate the stone's material likely originated from the Cotswolds, a source of oolitic limestone used in antiquity.[3]

Despite unsubstantiated legends portraying it as a Druidic relic, the foundational stone of Brutus of Troy, or the mystical "heart of London" whose disturbance portends the city's ruin—claims lacking empirical support—the stone's verified historical role underscores its status as a enduring civic symbol.[2][1]

A notable episode occurred in 1450 during Jack Cade's rebellion, when the Kentish leader struck the stone with his sword, proclaiming himself "Mayor of London" in a gesture of assumed authority.[2]

The stone has endured multiple relocations amid urban changes, including incorporation into St. Swithin's Church after the Great Fire of 1666, further moves in the 18th and 19th centuries, temporary storage at the Museum of London from 2016 to 2018, and its reinstatement at Cannon Street in a purpose-built setting; it holds Grade II listed status since the 1970s.[1][2]