Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lymph

View on Wikipedia

| Lymph | |

|---|---|

Human lymph, obtained after a thoracic duct injury | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Source | Formed from interstitial fluid |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lympha |

| MeSH | D008196 |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.043 |

| TA2 | 3893 |

| FMA | 9671 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Lymph (from Latin lympha 'water')[1] is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues to be recirculated. At the origin of the fluid-return process, interstitial fluid—the fluid between the cells in all body tissues[2]—enters the lymph capillaries. This lymphatic fluid is then transported via progressively larger lymphatic vessels through lymph nodes, where substances are removed by tissue lymphocytes and circulating lymphocytes are added to the fluid, before emptying ultimately into the right or the left subclavian vein, where it mixes with central venous blood.

Because it is derived from interstitial fluid, with which blood and surrounding cells continually exchange substances, lymph undergoes continual change in composition. It is generally similar to blood plasma, which is the fluid component of blood. Lymph returns proteins and excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream. Lymph also transports fats from the digestive system (beginning in the lacteals) to the blood via chylomicrons.

Bacteria may enter the lymph channels and be transported to lymph nodes, where the bacteria are destroyed. Metastatic cancer cells can also be transported via lymph.

Etymology

[edit]The word lymph is derived from the name of the ancient Roman deity of fresh water, Lympha.

Structure

[edit]Lymph has a composition similar to that of blood plasma. Lymph that leaves a lymph node is richer in lymphocytes than blood plasma is. The lymph formed in the human digestive system called chyle is rich in triglycerides (fat), and looks milky white because of its lipid content.

Development

[edit]

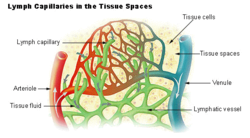

Blood supplies nutrients and important metabolites to the cells of a tissue and collects back the waste products they produce, which requires exchange of respective constituents between the blood and tissue cells. This exchange is not direct, but instead occurs through an intermediary called interstitial fluid, which occupies the spaces between cells. As the blood and the surrounding cells continually add and remove substances from the interstitial fluid, its composition continually changes. Water and solutes can pass between the interstitial fluid and blood via diffusion across gaps in capillary walls called intercellular clefts; thus, the blood and interstitial fluid are in dynamic equilibrium with each other.[3]

Interstitial fluid forms at the arterial (coming from the heart) end of capillaries because of the higher pressure of blood compared to veins, and most of it returns to its venous ends and venules; the rest (up to 10%) enters the lymph capillaries as lymph.[4] (Prior to entry, this fluid is referred to as the lymph obligatory load, or LOL, as the lymphatic system is effectively "obliged" to return it to the cardiovascular network.[5]) The lymph when formed is a watery clear liquid with the same composition as the interstitial fluid. However, as it flows through the lymph nodes it comes in contact with blood, and tends to accumulate more cells (particularly, lymphocytes) and proteins.[6]

Functions

[edit]Components

[edit]Lymph returns proteins and excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream. Lymph may pick up bacteria and transport them to lymph nodes, where the bacteria are destroyed. Metastatic cancer cells can also be transported via lymph. Lymph also transports fats from the digestive system (beginning in the lacteals) to the blood via chylomicrons.

Circulation

[edit]Tubular vessels transport lymph back to the blood, ultimately replacing the volume lost during the formation of the interstitial fluid. These channels are the lymphatic channels, or simply lymphatics.[7]

Unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system is not closed. In some amphibian and reptilian species, the lymphatic system has central pumps, called lymph hearts, which typically exist in pairs,[8][9] but humans and other mammals do not have a central lymph pump. Lymph transport is slow and sporadic.[8] Despite low pressure, lymph movement occurs due to peristalsis (propulsion of the lymph due to alternate contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle tissue), valves, and compression during contraction of adjacent skeletal muscle and arterial pulsation.[10]

Lymph that enters the lymph vessels from the interstitial spaces usually does not flow backwards along the vessels because of the presence of valves. If excessive hydrostatic pressure develops within the lymph vessels, though, some fluid can leak back into the interstitial spaces and contribute to formation of edema.

The flow of lymph in the thoracic duct in an average resting person usually approximates 100ml per hour. Accompanied by another ~25ml per hour in other lymph vessels, the total lymph flow in the body is about 4 to 5 litres per day. This can be elevated several fold while exercising. It is estimated that without lymphatic flow, the average resting person would die within 24 hours.[11]

Clinical significance

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2018) |

Histopathological analysis of lymphoid tissues is widely used in clinical diagnostics to evaluate immune system status and detect pathological conditions.[12] While it does not directly measure immune function, it offers valuable insights when combined with clinical and laboratory findings. Specific diagnostic applications include:

- Cancer diagnosis and staging: Examination of lymph node structure and cell types helps identify malignancies such as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Features like Reed-Sternberg cells or disrupted architecture are key indicators.

- Infectious disease evaluation:[13] Conditions like tuberculosis, HIV, and other systemic infections may cause characteristic lymph node changes, including granulomatous inflammation or lymphoid depletion.

- Autoimmune disease monitoring: In diseases such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, lymphoid tissues may show reactive hyperplasia or necrosis, reflecting underlying immune dysregulation.

- Transplant monitoring: In transplant recipients, lymph node biopsies may reveal signs of graft rejection, immune activation, or drug-induced immunosuppression.

- Immunohistochemical profiling: Use of antibody-based staining enhances diagnostic accuracy by distinguishing between reactive and neoplastic processes.

Beyond diagnosis, these assessments contribute to prognosis, treatment planning, and tracking of immune-related diseases over time.

As a growth medium

[edit]In 1907 the zoologist Ross Granville Harrison demonstrated the growth of frog nerve cell processes in a medium of clotted lymph. It is made up of lymph nodes and vessels.

In 1913, E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R. A. Lambert grew vaccinia virus in fragments of tissue culture from guinea pig cornea grown in lymph.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ "lymph". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ^ Fluid Physiology: 2.1 Fluid Compartments

- ^ "The Lymphatic System". Human Anatomy (Gray's Anatomy). Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Warwick, Roger; Peter L. Williams (1973) [1858]. "Angiology (Chapter 6)". Gray's anatomy. illustrated by Richard E. M. Moore (Thirty-fifth ed.). London: Longman. pp. 588–785.

- ^ Archer, Pat; Nelson, Lisa A. (2012). Applied Anatomy & Physiology for Manual Therapists. Wolters Kluwer Health. p. 604. ISBN 9781451179705.

- ^ Sloop, Charles H.; Ladislav Dory; Paul S. Roheim (March 1987). "Interstitial fluid lipoproteins" (PDF). Journal of Lipid Research. 28 (3): 225–237. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38701-0. PMID 3553402. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ "Definition of lymphatics". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary. MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ a b Hedrick, Michael S.; Hillman, Stanley S.; Drewes, Robert C.; Withers, Philip C. (1 July 2013). "Lymphatic regulation in nonmammalian vertebrates". Journal of Applied Physiology. 115 (3): 297–308. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00201.2013. ISSN 8750-7587. PMID 23640588.

- ^ Banda, Chihena H.; Shiraishi, Makoto; Mitsui, Kohei; Okada, Yoshimoto; Danno, Kanako; Ishiura, Ryohei; Maemura, Kaho; Chiba, Chikafumi; Mizoguchi, Akira; Imanaka-Yoshida, Kyoko; Maruyama, Kazuaki; Narushima, Mitsunaga (27 April 2023). "Structural and functional analysis of the newt lymphatic system". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 6902. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-34169-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10140069. PMID 37106059.

- ^ Shayan, Ramin; Achen, Marc G.; Stacker, Steven A. (2006). "Lymphatic vessels in cancer metastasis: bridging the gaps". Carcinogenesis. 27 (9): 1729–38. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl031. PMID 16597644.

- ^ Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Saunders. 2010. pp. 186, 187. ISBN 978-1416045748.

- ^ Mercadante, Anthony A.; Tadi, Prasanna (2025), "Histology, Lymph Nodes", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32644479, retrieved 11 July 2025

- ^ Ferrer, Robert (15 October 1998). "Lymphadenopathy: Differential Diagnosis and Evaluation". American Family Physician. 58 (6): 1313–1320.

- ^ Steinhardt, E; Israeli, C; and Lambert, R.A. (1913) "Studies on the cultivation of the virus of vaccinia" J. Inf Dis. 13, 294–300

External links

[edit] Media related to Lymph fluid at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lymph fluid at Wikimedia Commons

Lymph

View on GrokipediaHistory and Etymology

Etymology

The term "lymph" derives from the Latin lympha, signifying "clear water" or "pure fluid," which itself evolved from the Greek nymphe (νύμφη), originally denoting a bride, goddess, or mythical water spirit associated with springs and streams.[8][9] This connection reflects ancient Roman beliefs linking the fluid to nymphs, ethereal beings embodying fresh water, as the clear, limpid quality of lymph evoked these mythological figures.[10] The phonetic and semantic shift from Greek nymphe to Latin lympha occurred through cultural and linguistic adaptation in classical antiquity, where the term retained connotations of transparency and fluidity before its specialized application in medical contexts.[11][12] In linguistic evolution, lympha persisted in medieval Latin as a general descriptor for water, appearing in non-anatomical texts, but it was not until the 17th century that it was repurposed for bodily fluids in anatomical discourse. Danish anatomist Thomas Bartholin introduced the term vasa lymphatica (lymphatic vessels) in his 1653 publication Vasa lymphatica, marking the first documented medical usage to describe the clear fluid circulating in these structures, distinguishing it from earlier terms like vasa serosa.[13] This adoption built on the word's watery etymology, aligning with observations of the fluid's colorless, coagulable nature.[11] Related terminology includes "chyle," referring to the milky variant of lymph formed during fat digestion, derived from the Greek khylos (χυλός), meaning "juice" or "liquid pressed from plants."[14][15] This term, borrowed into Late Latin as chylus around the 16th century, entered English via French in the 1540s, emphasizing the emulsified, nutrient-rich quality of intestinal lymph.[16] Hippocrates alluded to similar concepts in the 5th century BCE by describing chylos in relation to glandular structures, though without modern anatomical precision.[17]Historical Background

The concept of lymph emerged in ancient medical observations, with Hippocrates in the 5th century BCE describing whitish, phlegmy glandular structures containing a fluid absorbed from tissues, located in areas such as the axilla, groin, and mesentery.[18] These descriptions, found in the Hippocratic treatise On the Glands, represented early recognition of lymphatic nodes as distinct from blood vessels, though their function remained unclear.[18] In the 2nd century CE, Galen built on this by noting networks of mesenteric vessels that transported a milky fluid from the intestines, which he interpreted as nutrient carriers to the liver, thus hinting at a vascular system separate from arterial and venous circulation.[19] The 17th century marked pivotal breakthroughs in lymphatic anatomy, beginning with Italian anatomist Gaspare Aselli's 1622 discovery of lacteal vessels during vivisection of a dog fed a fatty meal. Aselli observed numerous white, thread-like vessels in the mesentery carrying milky chyle from the intestines, publishing his findings in De lactibus sive lacteis venis (1627), which challenged Galenic theories of direct portal vein absorption by the liver.[20] In 1651, French anatomist Jean Pecquet identified the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli through vivisections on dogs, revealing how intestinal chyle flows into the venous system, thereby challenging prevailing Galenic theories of direct liver absorption.[21] This discovery clarified the pathway for lymph return to the bloodstream. Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck independently described the complete lymphatic system in humans that same year, tracing vessels from peripheral tissues to the thoracic duct in Nova exercitatio anatomica, though his work received less immediate recognition due to publication delays. The following year, Danish physician Thomas Bartholin extended these findings by mapping lymphatic vessels throughout the human body in his Historia Anatomica, demonstrating a widespread network that connected peripheral tissues to central ducts, establishing the lymphatic system as a distinct entity.[22] Advancements continued into the 18th and 19th centuries, where early misconceptions—such as confusing lymphatic vessels with nerves or blood-carrying channels due to their translucent appearance—were gradually dispelled by microscopic examination. British surgeon William Hewson, in the 1760s and 1770s, used rudimentary microscopes to detail lymph's cellular components, identifying colorless globules (precursors to lymphocytes) and their production in lymph nodes and glands, which differentiated lymph from blood serum.[23] These observations resolved prior interpretive errors rooted in macroscopic views alone.[24] By the 1890s, Ernest Starling integrated lymph into broader circulatory physiology, proposing the Starling forces—balancing hydrostatic and oncotic pressures—to explain fluid filtration from capillaries into tissues as the origin of lymph, thus linking it mechanistically to blood flow.[25]Composition

Cellular Components

Lymph, the fluid circulating through the lymphatic system, contains a variety of cells primarily derived from the blood and tissues, with lymphocytes forming the predominant cellular component. In afferent lymph, the fluid entering lymph nodes, lymphocytes typically constitute 85-95% of the total cells, while efferent lymph, exiting the nodes, is composed of over 99% lymphocytes.[26][27] These lymphocytes include T cells, which mature in the thymus and mediate cell-mediated immunity; B cells, which originate in the bone marrow and differentiate into antibody-producing plasma cells; and natural killer (NK) cells, also derived from bone marrow precursors and involved in innate immune responses.[28] Typical concentrations of lymphocytes in mammalian lymph range from 1,000 to 10,000 cells per microliter, though this can vary based on flow rates and physiological conditions, as observed in models where averages reach around 12,000 cells per microliter in mesenteric lymph.[7] Other cellular components include macrophages and dendritic cells, which comprise approximately 5-15% of cells in afferent lymph and function as phagocytic antigen-presenting cells derived from monocyte lineages in the blood.[26][29] These cells capture and process antigens in tissues before migrating via lymph to lymph nodes. Occasional erythrocytes or granulocytes may appear in lymph due to minor vascular leakage, but they are not typical residents.[4] Regional variations in cellular composition reflect the draining tissues; for instance, peripheral afferent lymph from skin often contains higher proportions of lymphocytes (85-90%), with 10-15% macrophages or dendritic cells, whereas intestinal lymph (chyle) may carry similar lymphocyte dominance but includes more lipid-laden cells from gut-associated tissues.[29] Lymphocytes exhibit dynamic turnover, recirculating from blood into tissues through peripheral endothelium, entering afferent lymph, passing through lymph nodes, and returning to blood via efferent lymph and the thoracic duct, with direct nodal entry facilitated by high endothelial venules.[26] This recirculation supports their role in immune surveillance, as detailed in the functions of the lymphatic system.Non-Cellular Components

Lymph's non-cellular components form a fluid matrix derived largely from interstitial fluid, consisting primarily of water along with dissolved proteins, lipids, and other solutes. This fluid base is approximately 95% water, contributing to a viscosity similar to that of blood plasma despite the lower overall protein content.[30][31] The protein fraction in lymph typically ranges from 2 to 4 g/dL, significantly lower than the 6 to 8 g/dL found in plasma, resulting in reduced oncotic pressure. Key proteins include albumins, which maintain osmotic balance; globulins, encompassing immunoglobulins for immune mediation; and trace amounts of fibrinogen. This composition varies by anatomical region: peripheral lymph has protein concentrations around 2 g/dL, while hepatic and intestinal lymph can reach 3 to 6 g/dL due to higher local filtration.[32][33][34] Lipids constitute another major non-cellular element, particularly in lymph from the gastrointestinal tract, where they form chyle—a milky fluid rich in triglycerides and chylomicrons, with concentrations varying from 4 to 40 g/L depending on dietary fat intake. In non-intestinal lymph, lipid levels are lower, primarily comprising free fatty acids and minimal chylomicrons.[35][1] Additional solutes mirror those in plasma to a large extent, including electrolytes such as sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions at concentrations similar to plasma levels (around 140 mEq/L for Na⁺ and 100 mEq/L for Cl⁻), along with glucose, urea, and metabolic waste products like lactate derived from tissue activity. These components ensure lymph's role in maintaining fluid and solute homeostasis without the higher protein load of plasma.[4][36]Formation and Flow

Formation

Lymph formation begins with the filtration of blood plasma across capillary walls into the surrounding interstitial space, governed by the Starling principle. This principle describes the balance between hydrostatic pressure, which drives fluid out of capillaries, and oncotic pressure exerted by plasma proteins, which opposes filtration and promotes reabsorption. At the arterial end of capillaries, hydrostatic pressure exceeds oncotic pressure, resulting in net filtration of water, electrolytes, and small solutes into the interstitium to form interstitial fluid. Although some fluid is reabsorbed at the venous end where hydrostatic pressure decreases, a portion—approximately 10-20% of the filtered volume—remains in the tissues due to incomplete reabsorption, becoming the precursor to lymph.[37] This interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic system through specialized blind-ended lymphatic capillaries, known as initial lymphatics. These capillaries feature thin, overlapping endothelial cells with loose junctions that allow passive uptake of fluid, proteins, and cells from the interstitium. Anchoring filaments, composed of elastic fibers, tether the endothelial cells to the surrounding extracellular matrix; increased interstitial pressure stretches these filaments, widening the intercellular gaps to facilitate fluid entry while preventing backflow due to one-way valve-like overlaps.[38] In healthy adults, lymph production totals about 2-4 liters per day, equivalent to the volume of interstitial fluid not reabsorbed by blood capillaries, ensuring fluid balance and preventing tissue edema. Formation rates vary regionally, with the liver and intestines accounting for roughly 80% of total lymph volume due to high filtration demands in these metabolically active organs. Factors such as elevated venous pressure, which raises capillary hydrostatic pressure, acute inflammation that increases vascular permeability, and physical exercise that enhances overall filtration, can significantly increase lymph production to maintain homeostasis.[1][1][39]Circulation

The lymphatic vasculature forms a hierarchical network beginning with blind-ended lymphatic capillaries that collect interstitial fluid and proteins from tissues. These capillaries converge into larger collecting vessels, which feature one-way valves to ensure unidirectional flow. Collecting vessels further merge into afferent lymphatic vessels that deliver lymph to lymph nodes for filtration. Within and beyond nodes, efferent vessels continue the drainage, ultimately forming major trunks: the thoracic duct, which collects lymph from approximately 75% of the body (including the lower limbs, abdomen, left thorax, and left upper limb) and empties into the left subclavian vein, and the right lymphatic duct, which drains the remaining ~25% (right upper limb, right thorax, and right side of the head and neck) into the right subclavian vein.[1][40] Lymph propulsion relies on both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms to overcome low pressure gradients of 5–30 cm H₂O. Intrinsic propulsion arises from rhythmic contractions of smooth muscle cells in the walls of collecting vessels, segmenting them into functional units called lymphangions; these contractions generate peristaltic-like waves that propel lymph forward, with valves preventing backflow. Extrinsic forces augment this process through external compression: skeletal muscle contractions during movement act as a pump, respiratory movements create thoracic-abdominal pressure differentials, and arterial pulsations provide rhythmic external pressure.[41][42][43] At rest, total lymph flow in humans averages 1–2 mL/min, increasing up to 10-fold during physical activity due to enhanced extrinsic pumping and intrinsic contractility. Upon reaching lymph nodes—approximately 500–600 in the human body—flow slows significantly, allowing macrophages and other immune cells to scan and filter lymph for pathogens and antigens before it exits via efferent vessels. This nodal filtration processes the entire lymph volume, ensuring immune surveillance without impeding overall circulation.[44][45]Functions

Immune Functions

Lymph serves as a vital conduit for immune surveillance, transporting antigens, pathogens, and immune cells from peripheral tissues to regional lymph nodes, where adaptive immune responses are initiated and coordinated.[46] This process enables the lymphatic system to actively participate in immunity beyond mere fluid drainage, by facilitating interactions between antigen-presenting cells and lymphocytes.[29] Dendritic cells, capturing antigens in tissues, migrate through afferent lymphatic vessels in lymph to reach lymph nodes, presenting these antigens to naive T and B cells to trigger specific immune activation.[47] Soluble antigens and particulate matter are similarly carried in lymph flow, concentrating them in lymph node sinuses for efficient detection and processing by resident immune cells.[48] Lymphocyte recirculation is a fundamental aspect of immune homeostasis, allowing naive lymphocytes to continuously survey peripheral tissues for threats. Naive T and B lymphocytes primarily enter lymph nodes from the blood via specialized high endothelial venules (HEVs), which express adhesion molecules that facilitate selective lymphocyte extravasation.[49] Within the lymph node, these cells encounter antigens presented by dendritic cells; upon activation, they proliferate and differentiate into effector cells, such as memory T cells or antibody-secreting B cells.[50] Activated and memory lymphocytes then exit the lymph node through efferent lymphatic vessels, re-entering the bloodstream via the thoracic duct to patrol distant sites, thereby disseminating the immune response.[51] This recirculation pathway, involving both blood and lymph, ensures broad immune coverage and rapid response amplification. Lymph contains key lymphocyte subsets, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells, which underpin these dynamics.[52] The lymphatic system also maintains immune tolerance, preventing autoimmunity while enabling targeted responses to foreign threats. Central tolerance eliminates self-reactive lymphocytes during development in the thymus and bone marrow, establishing a baseline repertoire of non-autoreactive cells.[53] Peripheral tolerance, enforced in secondary lymphoid organs like lymph nodes, further suppresses escaped self-reactive cells through mechanisms such as deletion, anergy, or regulatory T cell induction, with lymph node-resident lymphatic endothelial cells playing a direct role in promoting T cell tolerance via antigen presentation and costimulatory signals.[54] By channeling antigens to these structured environments, lymph concentrates effectors and supports the maturation of adaptive immunity, allowing precise discrimination between self and non-self.[55] In inflammatory contexts, lymph contributes to response coordination by carrying cytokines and other mediators that amplify signaling between immune cells and the vasculature. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1, transported in lymph, stimulate lymphatic endothelial cells to enhance vessel permeability and contractility, thereby accelerating antigen and cell delivery to lymph nodes.[56] Concurrently, lymphatics drain excess interstitial fluid laden with inflammatory exudates, mitigating tissue edema and maintaining an environment conducive to immune cell migration and function.[57] This dual role—signal amplification and fluid clearance—helps resolve inflammation while preventing chronic swelling that could impair immune surveillance.[55]Transport Functions

Lymph plays a crucial role in maintaining fluid homeostasis by returning approximately 3 liters of interstitial fluid per day from the tissues to the bloodstream, which matches the volume of fluid filtered out of capillaries that is not reabsorbed by the venous system.[58] This process prevents the accumulation of excess fluid in the interstitium, thereby averting edema formation.[4] In addition to fluid, lymph salvages proteins such as albumins and globulins that have leaked from the capillaries into the interstitial space, returning them to the circulation to sustain plasma oncotic pressure.[59] Failure of this protein recovery mechanism can result in hypoproteinemia, leading to reduced oncotic pressure and subsequent edema.[59] Lymph is essential for dietary lipid absorption, as intestinal lacteals uptake chylomicrons—lipoprotein particles assembled by enterocytes from absorbed fats—and transport them as chyle to the cisterna chyli for eventual delivery to the bloodstream.[60] This pathway is vital for the absorption and distribution of fat-soluble vitamins, ensuring their availability for various physiological processes.[60] Furthermore, lymph facilitates waste removal by carrying cellular debris and excess metabolites from tissues to lymph nodes or directly to the blood for clearance and processing.[61] This transport helps maintain tissue integrity by eliminating accumulated byproducts of cellular activity.[62]Clinical Significance

Disorders

Disorders of the lymphatic system encompass a range of pathological conditions arising from impaired lymph flow, accumulation, or dysfunction, leading to significant morbidity. Lymphedema, characterized by chronic swelling due to lymphatic fluid buildup, represents one of the primary disorders, manifesting as tissue fibrosis, heaviness, tightness, and reduced mobility in affected limbs.[63] Primary lymphedema stems from genetic anomalies in lymphatic development, such as Milroy disease, an autosomal dominant condition caused by mutations in the FLT4 gene, resulting in congenital swelling typically in the lower legs and feet from birth or infancy.[64] This form is rare, affecting approximately 1 in 100,000 individuals.[63] In contrast, secondary lymphedema, the more prevalent type impacting about 1 in 1,000 people, develops from acquired damage to lymphatic vessels, including surgical interventions like lymph node dissection or parasitic infections such as filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, which obstructs lymphatics and promotes fibrosis.[65] Risk factors for secondary lymphedema include obesity, which exacerbates lymphatic overload, and radiation therapy, which induces fibrosis in treated areas.[66] Infections can directly compromise lymphatic integrity, with lymphangitis involving acute bacterial invasion—most commonly by streptococci—along lymphatic vessels, often originating from a distal skin wound and presenting as erythematous streaks with fever and lymphadenopathy.[67] Chronic infections like lymphatic filariasis, transmitted by mosquitoes carrying Wuchereria bancrofti, lead to elephantiasis through progressive lymphatic blockage, inflammation, and secondary bacterial superinfections, causing massive limb enlargement and skin thickening.[68] Malignancies frequently involve the lymphatic system, as lymphoma originates from uncontrolled proliferation of lymphocytes within lymph nodes or vessels, resulting in painless nodal enlargement, systemic symptoms like fever and weight loss, and potential dissemination via lymphatics.[69] Additionally, solid tumors exploit lymphatic pathways for metastasis; in breast cancer, malignant cells spread to axillary lymph nodes and subsequently to skin, forming nodules or plaques through lymphatic invasion, while in skin cancers such as melanoma, lymphatic vessels facilitate regional and distant dissemination.[70] Other lymphatic disorders include chylothorax, where chyle—a lipid-rich lymphatic fluid—leaks into the thoracic cavity due to thoracic duct disruption, often from trauma or malignancy, leading to pleural effusions, dyspnea, and nutritional deficits.[71] Lymphocytopenia, a reduction in circulating lymphocytes below normal levels, occurs in various immunodeficiencies, impairing immune surveillance and increasing susceptibility to infections, as seen in conditions like severe combined immunodeficiency or HIV-related depletion.[72]Applications

Lymphangiography is a diagnostic imaging technique that employs contrast agents, such as Lipiodol, injected into lymphatic vessels to visualize the lymphatic system via X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging, aiding in the identification of lymphatic leaks, malformations, or obstructions.[73][74] Sentinel lymph node biopsy involves the surgical removal and pathological examination of the first lymph node(s) to receive drainage from a tumor site, marked by injected tracers like blue dye or radioactive substances, to assess cancer metastasis and stage malignancies such as breast cancer or melanoma.[75][76] Flow cytometry applied to lymph samples enables detailed immune profiling by analyzing cell surface markers on lymphocytes and other immune cells, facilitating the diagnosis and monitoring of lymphoproliferative disorders through multiparameter assessment of cell populations.[77][78] Therapeutic interventions targeting the lymphatic system include manual lymphatic drainage massage, a gentle, specialized technique that stimulates lymph flow to reduce swelling in conditions like lymphedema by promoting fluid movement toward functional lymph nodes.[79][80] Compression therapy utilizes garments or bandages to apply graduated external pressure, countering fluid accumulation and maintaining reduced limb volume in lymphedema patients, with long-term efficacy observed in up to 90% of cases when combined with other measures.[81][82] Emerging therapies involve drugs or gene constructs targeting vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C), which promotes lymphatic vessel regeneration; for instance, VEGF-C gene therapy has demonstrated augmentation of postnatal lymphangiogenesis and amelioration of lymphedema in preclinical models by enhancing endothelial cell proliferation and vessel sprouting.[83][84] Additionally, nucleoside-modified VEGF-C mRNA formulations have shown organ-specific lymphatic growth in vivo, supporting potential clinical translation for restoring lymphatic function post-injury.[84] Historically, lymph served as a nutrient-rich medium in early tissue culture experiments; in the 1910s, Warren H. Lewis utilized plasma to sustain organ cultures, observing robust fibroblast growth in chick embryo tissues before transitioning to simpler saline solutions.[85] Alexis Carrel, collaborating with researchers like Montrose Burrows, advanced these methods by culturing whole organ fragments in plasma-based media, achieving prolonged viability and growth in chicken heart tissues, which laid foundational techniques for modern cell biology despite initial reliance on biological fluids like lymph.[86][87] In contemporary research as of 2025, intralymphatic injection has emerged as a strategy for vaccine delivery, bypassing peripheral barriers to directly access lymph nodes and enhance immune responses; clinical trials have demonstrated that this approach significantly reduces required doses, often by 100-fold or more, while accelerating specific immunity in models of allergen sensitization and infectious diseases.[88][89] Lymphatic targeting also plays a pivotal role in immunotherapy for autoimmune diseases, with nanomedicine platforms designed for lymph node-specific delivery of antigens or tolerogenic agents showing promise in modulating autoreactive T cells; recent studies highlight defined distribution parameters for these therapies, enabling sustained immune suppression in preclinical autoimmune models without systemic off-target effects.[90][91]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lymph

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/chyle