Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

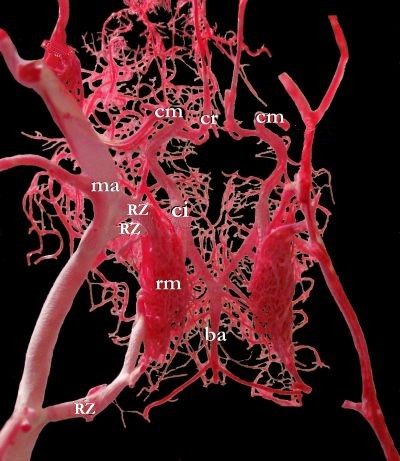

Rete mirabile

View on Wikipedia| Rete mirabile | |

|---|---|

Rete mirabile of a sheep | |

| Identifiers | |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.013 |

| TA2 | 3928 |

| FMA | 76728 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A rete mirabile (Latin for "wonderful net"; pl.: retia mirabilia) is a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other, found in some vertebrates, mainly warm-blooded ones. The rete mirabile utilizes countercurrent blood flow within the net (blood flowing in opposite directions) to act as a countercurrent exchanger. It exchanges heat, ions, or gases between vessel walls so that the two bloodstreams within the rete maintain a gradient with respect to temperature, or concentration of gases or solutes. This term was coined by Galen.[1][2]

Effectiveness

[edit]The effectiveness of retia is primarily determined by how readily the heat, ions, or gases can be exchanged. For a given length, they are most effective with respect to gases or heat, then small ions, and decreasingly so with respect to other substances.[citation needed]

The retia can provide for extremely efficient exchanges. In bluefin tuna, for example, nearly all of the metabolic heat in the venous blood is transferred to the arterial blood, thus conserving muscle temperature; that heat exchange approaches 99% efficiency.[3][4]

Birds

[edit]In birds with webbed feet, retia mirabilia in the legs and feet transfer heat from the outgoing (hot) blood in the arteries to the incoming (cold) blood in the veins. The effect of this biological heat exchanger is that the internal temperature of the feet is much closer to the ambient temperature, thus reducing heat loss. Penguins also have them in the flippers and nasal passages.

Seabirds distill seawater using countercurrent exchange in a so-called salt gland with a rete mirabile. The gland secretes highly concentrated brine stored near the nostrils above the beak. The bird then "sneezes" the brine out. As freshwater is not usually available in their environments, some seabirds, such as pelicans, petrels, albatrosses, gulls and terns, possess this gland, which allows them to drink the salty water from their environments while they are hundreds of miles away from land.[5][6]

Fish

[edit]Fish have evolved retia mirabilia multiple times to raise the temperature[7] (endothermy) or the oxygen concentration of a body part above the ambient level.[8]

In many fish, a rete mirabile helps fill the swim bladder with oxygen, increasing the fish's buoyancy. The rete mirabile is an essential[8] part of the system that pumps dissolved oxygen from a low partial pressure () of 0.2 atmospheres into a gas filled bladder that is at a pressure of hundreds of atmospheres.[9] A rete mirabile called the choroid rete mirabile is found in most living teleosts and raises the of the retina.[8] The higher supply of oxygen allows the teleost retina to be thick and have few blood vessels thereby increasing its sensitivity to light.[10] In addition to raising the , the choroid rete has evolved to raise the temperature of the eye in some teleosts and sharks.[7]

A countercurrent exchange system is utilized between the venous and arterial capillaries. Lowering the pH levels in the venous capillaries causes oxygen to unbind from blood hemoglobin because of the Root effect. This causes an increase in venous blood oxygen partial pressure, allowing the oxygen to diffuse through the capillary membrane and into the arterial capillaries, where oxygen is still sequestered to hemoglobin. The cycle of diffusion continues until the partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial capillaries exceeds that in the swim bladder. At this point, the dissolved oxygen in the arterial capillaries diffuses into the swim bladder via the gas gland.[11]

The rete mirabile allows for an increase in muscle temperature in regions where this network of vein and arteries is found. The fish is able to thermoregulate certain areas of its body. Additionally, this increase in temperature leads to an increase in basal metabolic temperature. The fish is now able to split ATP at a higher rate and ultimately can swim faster.

The opah utilizes retia mirabilia to conserve heat, making it the newest addition to the list of regionally endothermic fish. Blood traveling through capillaries in the gills must carry cold blood due to their exposure to cold water, but retia mirabilia in the opah's gills are able to transfer heat from warm blood in arterioles coming from the heart that heats this colder blood in arterioles leaving the gills. The huge pectoral muscles of the opah, which generate most of the body heat, are thus able to control the temperature of the rest of the body.[12]

Mammals

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

In mammals, an elegant rete mirabile in the efferent arterioles of juxtamedullary glomeruli is important in maintaining the hypertonicity of the renal medulla. It is the hypertonicity of this zone, resorbing water osmotically from the renal collecting ducts as they exit the kidney, that makes possible the excretion of a hypertonic urine and maximum conservation of body water.

Vascular retia mirabilia are also found in the limbs of a range of mammals. These reduce the temperature in the extremities. Some of these probably function to prevent heat loss in cold conditions by reducing the temperature gradient between the limb and the environment. Others reduce the temperature of the testes increasing their productivity. In the neck of the dog, a rete mirabile protects the brain when the body overheats during hunting; the venous blood is cooled down by panting before entering the net.

Retia mirabilia also occur frequently in mammals that burrow, dive or have arboreal lifestyles that involve clinging with the limbs for lengthy periods. In the last case, slow-moving arboreal mammals such as sloths, lorises and arboreal anteaters possess retia of the highly developed type known as vascular bundles. The structure and function of these mammalian retia mirabilia are reviewed by O'Dea (1990).[13]

The ancient physician Galen mistakenly thought that humans also have a rete mirabile in the neck, apparently based on dissection of sheep and misidentifying the results with the human carotid sinus, and ascribed important properties to it; it fell to Berengario da Carpi first, and then to Vesalius to demonstrate the error.

See also

[edit]- Pampiniform plexus, a countercurrent heat-exchanging structure in the spermatic cord

References

[edit]- ^ Grant, Mark (2000). Galen on Food and Diet. Routledge.

- ^ "Rete Mirabile". encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Cech, Joseph J.; Laurs, R. Michael; Graham, Jeffrey B. (March 1, 1984). "Temperature-Induced Changes in Blood Gas Equilibria in the Albacore, Thunnus alalunga, a Warm-Bodied Tuna". Journal of Experimental Biology. 109 (1): 21–34. doi:10.1242/jeb.109.1.21.

- ^ Taylor, Richard C. (30 April 1982). A Companion to Animal Physiology. CUP Archive. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-24437-4.

- ^ Proctor, Noble S.; Lynch, Patrick J. (1993). Manual of Ornithology. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07619-3.

- ^ Ritchison, Gary. "Avian osmoregulation » Urinary System, Salt Glands, and Osmoregulation". Retrieved 16 April 2011. including images of the gland and its function

- ^ a b Runcie, Rosa M.; Dewar, Heidi; Hawn, Donald R.; Frank, Lawrence R.; Dickson, Kathryn A. (2009-02-15). "Evidence for cranial endothermy in the opah (Lampris guttatus)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (4): 461–470. doi:10.1242/jeb.022814. eISSN 1477-9145. ISSN 0022-0949. PMC 2726851. PMID 19181893.

- ^ a b c Berenbrink, Michael (2007-05-01). "Historical reconstructions of evolving physiological complexity: O2 secretion in the eye and swimbladder of fishes". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (9): 1641–1652. doi:10.1242/jeb.003319. eISSN 1477-9145. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 17449830. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Pelster, Bernd (2001-12-01). "The Generation of Hyperbaric Oxygen Tensions in Fish". Physiology. 16 (6): 287–291. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.287. ISSN 1548-9213. PMID 11719607. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Damsgaard, Christian (2021-02-01). "Physiology and evolution of oxygen secreting mechanism in the fisheye". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 252 110840. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.110840. ISSN 1095-6433. PMID 33166685.

- ^ Kardong, K. (2008). Vertebrates: Comparative anatomy, function, evolution (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Wegner, Nicholas C.; Snodgrass, Owyn E.; Dewar, Heidi; Hyde, John R. (15 May 2015). "Whole-body endothermy in a mesopelagic fish, the opah, Lampris guttatus". Science. 348 (6236): 786–789. Bibcode:2015Sci...348..786W. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8902. PMID 25977549. S2CID 17412022.

- ^ O'Dea, J. D (1990). "The mammalian Rete mirabile and oxygen availability". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 95A (1): 23–25. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(90)90004-C.

External links

[edit]Rete mirabile

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Physiology

Definition and Structure

The rete mirabile, a Latin term translating to "wonderful net," refers to an intricate vascular network composed of small arteries (arterioles) and veins (venules) arranged in close proximity without direct anastomosis between the arterial and venous components.[9] This structure facilitates efficient exchange across vessel walls due to the intimate apposition of the parallel-running arterioles and venules, which form counter-current exchangers oriented in opposite directions.[10] In cross-sections, the organization often appears as ladder-like or hexagonal patterns, reflecting the bundled, interwoven layout of the vessels that maximizes surface area for diffusion while maintaining separate blood flows.[11][12] The basic components include afferent arterioles branching from a primary artery, which then intertwine with efferent venules draining into a collecting vein, creating a dense meshwork without significant branching or looping within the rete itself.[13] Vessel diameters typically range from 10 to 130 μm, depending on the specific rete type, with the network embedded in connective tissue that supports the parallel alignment.[9] Endothelial cells lining the vessels exhibit specializations for permeability, such as fenestrations in the venous endothelium and unperforated, tightly overlapping cells in the arterial side, enhancing selective barrier properties.[14] Rete mirabilia vary considerably in size and density across vertebrates, from microscopic scales in structures like the choroid rete, where capillaries measure 10–20 μm and form compact bundles totaling kilometers of aggregate length in some species, to more macroscopic forms such as the epidural rete in mammals, which presents as a spongy, visible meshwork occupying larger volumes within dural spaces.[10] Histologically, these networks feature thin vessel walls with minimal tunica media in capillary-like segments—often lacking smooth muscle entirely in gas-exchange types for reduced resistance—and exceptionally high capillary density, enabling close packing that supports the counter-current configuration.[15] The tunica intima includes a fenestrated internal elastic lamina in some arterial components, while the surrounding adventitia shares elements with adjacent venous sinuses, incorporating collagen, elastic fibers, and fibroblasts for structural integrity.General Functions

The rete mirabile primarily serves as a counter-current multiplier system that facilitates the efficient exchange of heat, gases, or solutes between arterial and venous blood flows traveling in opposite directions.[9] This arrangement allows for the establishment and preservation of steep gradients along the vascular network, enabling near-complete transfer of properties without significant mixing of the blood streams.[9] In the context of thermoregulation, warm arterial blood entering the rete transfers heat to cooler venous blood returning from peripheral regions, thereby conserving metabolic heat and minimizing losses to cooler surroundings.[10] The mechanism operates via passive diffusion across the thin walls of closely apposed arterioles and venules, where the countercurrent flow maintains a consistent temperature differential; this contrasts with parallel flow systems, which would equilibrate temperatures more rapidly and reduce efficiency.[9] Heat transfer in the rete follows the relation , where represents heat flux, is the convective heat transfer coefficient, is the effective surface area for exchange, and is the temperature difference between the streams; the structure maximizes through its extensive capillary meshwork while the opposing flows minimize axial mixing to sustain .[10] In certain fish species, pH modulation via mechanisms like the Root effect optimizes oxygen delivery by reducing hemoglobin-oxygen affinity and promoting unloading to tissues such as the retina.[16] It contributes to pressure equalization by distributing and damping high arterial pressures in downstream circulations.[17] The overall efficiency of exchange in the rete mirabile, which can exceed 97% for heat retention in well-vascularized systems, depends critically on blood flow rates (slower flows enhance equilibration), vessel proximity (reducing diffusion distances), and surface area (scaled by capillary density and length).[18] These factors collectively enable the rete to achieve high recovery rates, often 90-98%, far surpassing simpler vascular arrangements.[18]Occurrence in Vertebrates

In Fish

In fish, the rete mirabile is most prominently associated with the swimbladder, where it forms a counter-current exchange system in the gas gland to multiply the partial pressures of oxygen and nitrogen, thereby facilitating active gas secretion for buoyancy regulation. This structure consists of an intricate network of arterial and venous capillaries arranged in parallel, allowing oxygenated blood from the gas gland to exchange gases with deoxygenated blood flowing in the opposite direction, progressively concentrating gases against the hydrostatic pressure of the aquatic environment. The rete mirabile is prevalent in both physostomous fish, which possess a pneumatic duct for air gulping, and physoclistous fish, which rely entirely on it for gas filling due to their closed swimbladder; however, it is more extensively developed in physoclistous species to enable independent depth adjustments without surfacing.[19] The mechanism of gas secretion begins in the gas gland epithelium, where cells produce lactic acid, which diffuses into the blood and lowers its pH; this acidification exploits the Root effect—a unique property of fish hemoglobin that reduces its oxygen-binding affinity, promoting oxygen unloading even at high partial pressures. The rete mirabile then amplifies this initial oxygen release through repeated counter-current cycles, generating gas tensions that can exceed 100 atm for oxygen in shallow-water species and reach up to 140 atm or more in deep-sea fish, sufficient to counter ambient pressures at depths beyond 700 meters. This process not only maintains neutral buoyancy but also prevents collapse of the swimbladder under pressure gradients.[20][21] A second major occurrence is the choroid rete mirabile, a specialized vascular bed positioned immediately posterior to the retina in many teleost fish, designed to deliver elevated oxygen levels directly to the high-metabolic demands of photoreceptor cells. Similar to the swimbladder rete, it employs localized pH reduction via lactic acid secretion in the choriocapillaris, triggering the Root effect to boost oxygen diffusion across the retinal barrier and sustain visual function in low-oxygen aquatic conditions. This adaptation is particularly vital in species with large, energy-intensive eyes, ensuring photoreceptors receive partial pressures of oxygen far above arterial levels without systemic hyperoxia.[22][23] In deep-sea fish, such as certain gadiforms and stomiiforms, the swimbladder rete mirabile exhibits structural modifications for pressure tolerance, including elongated, sausage-shaped capillary bundles that enhance the efficiency of counter-current multiplication while resisting compression at extreme depths. These adaptations allow species like the rattail fish (Coryphaenoides spp.) to maintain buoyancy and gas homeostasis in habitats exceeding 4,000 meters, where hydrostatic pressures approach 400 atm.[24]In Birds

In birds, the rete mirabile primarily functions in thermoregulation through counter-current heat exchange systems located in the legs and nasal passages, which help prevent excessive heat loss from uninsulated extremities and maintain core temperature during environmental stresses like cold exposure or high metabolic demands.[25] These networks consist of intertwined arteries and veins that facilitate efficient thermal transfer, allowing arterial blood to be preconditioned by venous blood flowing in the opposite direction.[26] The leg rete mirabile, often termed the rete tibiotarsale, is situated in the lower hindlimb where multiple small arteries and veins interweave to form a dense vascular plexus. This structure warms incoming arterial blood to the feet using heat from outgoing venous blood returning from the cooler extremities to the body core, thereby maintaining foot temperatures well above ambient levels even in subzero conditions.[25] Such adaptation is particularly vital for perching and locomotion in cold climates, as it minimizes conductive heat loss through the unfeathered legs while permitting controlled vasodilation for heat dissipation when needed. In the nasal passages, the rete mirabile—commonly the ophthalmic or post-orbital rete—enables selective brain cooling by allowing cooled venous blood from the respiratory mucosa and nasal surfaces to exchange heat with warmer arterial blood supplying the brain. During hyperthermia, such as from prolonged flight or heat stress, evaporative cooling in the nasal cavity chills the venous return, which then reduces arterial blood temperature via counter-flow, protecting neural tissues from overheating without broadly lowering body temperature.[26] This mechanism can lower brain temperature by up to 1–3°C relative to the core, supporting sustained cognitive function under thermal duress.[28] These retia are especially well-developed in penguins, where the leg rete tibiotarsale and post-orbital nasal rete conserve heat in icy aquatic environments, and in migratory birds like eiders and mallards, which rely on them to retain 80–90% of generated heat during long-distance flights over cold regions.[29][30] In these species, the efficiency of the counter-current systems ensures minimal thermal leakage, enabling endurance in extreme conditions without compromising insulation elsewhere on the body.[25]In Mammals

In mammals, the rete mirabile primarily facilitates selective brain cooling, a thermoregulatory mechanism that protects neural tissue from hyperthermia by reducing brain temperature below core body levels. This is most prominently observed in artiodactyls, such as cattle and goats, where the carotid rete mirabile—a network of fine, interconnected arteries—arises from the maxillary and ascending pharyngeal arteries and lies within the cavernous sinus at the base of the brain. Complementing this, the rostral epidural rete mirabile, an intracranial extension embedded in the dura mater near the hypophysis, further enhances heat dissipation in these species. Venous blood cooled at nasal and mucosal surfaces flows through the cavernous sinus, enabling countercurrent heat exchange that lowers the temperature of arterial blood supplying the brain.[31] During exercise-induced hyperthermia, this system reduces brain temperature by approximately 2–4°C relative to arterial blood, thereby mitigating heat stress and preserving cognitive function while allowing peripheral hyperthermia to aid overall cooling. The mechanism also supports maintenance of hypothalamic thermoregulatory set points, preventing overheating of this critical region and enabling sustained evaporative cooling responses like panting. In arid-adapted artiodactyls, such as the Arabian oryx, this adaptation conserves body water by minimizing respiratory evaporation needs, with selective brain cooling activated above a threshold of about 39°C. Other mammalian retia occur in distinct locations with specialized roles. In felids like domestic cats, the extracranial maxillary rete mirabile, formed by the maxillary artery in the pterygoid fossa, supplies oxygenated blood to the orbit and cerebral arteries via the orbital fissure, while also contributing to brain cooling during heat exposure through interactions with the cavernous sinus.[3] In cetaceans, such as porpoises and whales, a prominent thoracic rete mirabile—a dense arterial plexus on the dorsal surface of the thoracic cavity—plays key roles in dive physiology and cerebral protection. This structure provides vascular shunts that isolate circulation to skeletal muscles during dives, enhancing oxygen storage in the blood and lungs for prolonged submersion. Additionally, it filters blood pressure pulses generated by swimming, stabilizing cerebral blood flow and preventing barotrauma during ascent and descent.[32][33] Notably, the rete is absent in small tropical ruminants, such as the lesser and greater mouse deer (Tragulus spp.), which inhabit humid, shaded forests where extreme heat stress is rare; these species retain a direct internal carotid artery for brain supply, reflecting environmental adaptations that reduce the selective pressure for elaborate cooling structures.[34]Evolutionary Aspects

Origins and Development

The rete mirabile first emerged in the choroid of early actinopterygian fishes approximately 250 million years ago, in the common ancestor of bowfin (Amia calva) and teleosts, as a countercurrent exchanger to enhance retinal oxygenation in avascular retinas.[35] This adaptation was facilitated by prior evolutionary changes, including the Root effect in hemoglobin and low hemoglobin buffer values, which enabled oxygen secretion against high partial pressures.[35] The choroid rete allowed for thicker retinas and improved visual acuity, marking a key milestone in vertebrate eye evolution during the Permian-Triassic transition.[5] Phylogenetically, the rete mirabile evolved independently across multiple vertebrate lineages, reflecting convergent responses to oxygenation demands. In teleost fishes, the gas gland rete mirabile arose later, around 150 million years ago in elopomorphs and euteleosts, approximately 100 million years after the ocular system, and diversified the swim bladder's role in buoyancy control and auditory function.[36] This development coincided with the adaptive radiation of teleosts in the Jurassic, enabling gas secretion into the swim bladder via countercurrent multiplication.[36] Thermoregulatory retes, such as the carotid rete in artiodactyl mammals, emerged later in the Eocene around 55 million years ago, enhancing brain cooling and contributing to ecological success in variable climates.[37] Fossil evidence for retia mirabilia is indirect, primarily inferred from the anatomy of extant basal actinopterygians like gars and bowfins, which retain primitive traits predating the rete's origin.[35]Comparative Variations

The rete mirabile exhibits notable structural variations across vertebrate classes, reflecting adaptations to distinct physiological demands. In fish, particularly teleosts, the rete mirabile—such as the swimbladder and choroid forms—consists of elongated, parallel arterioles and venules arranged in a countercurrent configuration, with thin walls and extensive capillary networks tolerant of high hydrostatic pressures up to several hundred atmospheres in deep-sea species.[38] In contrast, mammalian retes, exemplified by the rostral epidural rete mirabile in artiodactyls and cetaceans, form dense, spongy anastomosing arterial plexuses integrated within the epidural space and cavernous sinus, featuring thick smooth muscle layers for contractility and proximity to dural structures to facilitate precise heat exchange.[17] Avian retes, such as the orbital region (rete ophthalmicum), are more peripheral and compact, often embedded in feather-insulated tissues to minimize exposure, with anastomotic vessels branching from major arteries like the temporo-orbital and draining via accompanying veins.[26] Functionally, these structures diverge in primary roles, with fish retes emphasizing gas exchange through countercurrent multiplication, as seen in the choroid rete's ability to generate oxygen partial pressures exceeding 1300 mmHg via pH-mediated Root effect hemoglobin unloading, prioritizing pressure tolerance over thermal regulation.[5] In birds and mammals, retes primarily serve thermoregulation via countercurrent heat exchange, cooling arterial blood by 1–4°C before it reaches the brain or eyes; for instance, the avian rete ophthalmicum maintains ocular temperature gradients essential for vision in varying climates, while mammalian carotid retes reduce hypothalamic temperatures to avert hyperthermia.[26][39] Efficiency trade-offs are evident, as fish retes sacrifice thermal insulation for gas secretion efficiency under compression, whereas endotherm retes optimize heat retention or dissipation at the expense of gas-handling capacity.[38] Environmental adaptations further highlight these variations. Deep-sea fish retes, like the swimbladder rete, incorporate robust capillary reinforcements to secrete gases against hyperbaric conditions, enabling buoyancy control at depths beyond 1000 meters without structural collapse.[38] In desert-dwelling artiodactyls, such as the Arabian oryx, the carotid rete enhances selective brain cooling during panting, conserving up to 60% of daily water expenditure (e.g., 2.4 liters in a 50 kg animal) by minimizing evaporative nasal cooling needs in arid environments.[39] The rete mirabile shows patterns of loss and convergent evolution across lineages. It is absent in primates and humans, where direct internal carotid arteries supply the brain without such plexuses, likely an evolutionary loss linked to upright posture and reduced need for selective cooling.[40] Convergent evolution has produced similar thermoregulatory retes independently in unrelated endotherms, including birds (for peripheral heat conservation) and mammals (for cerebral protection), arising over 45 million years ago in response to endothermy's metabolic demands.[39][26]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/230032792_The_Rete_tibiotarsale_and_Arteriovenous_Association_in_the_Hind_Limb_of_Birds_A_Compartive_Morphological_Study_on_Counter-current_Heat_Exchange_Systems