Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

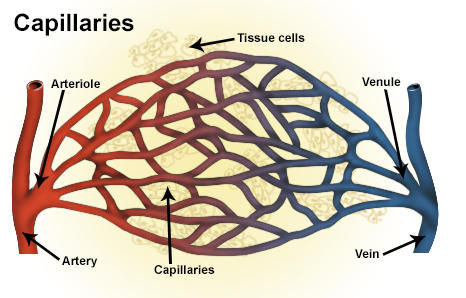

Venule

View on Wikipedia| Venule | |

|---|---|

Types of blood vessels, including a venule, vein, and capillaries | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | venula |

| MeSH | D014699 |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.037 |

| TA2 | 3903 |

| TH | H3.09.02.0.03002 |

| FMA | 63130 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A venule is a very small vein in the microcirculation that allows blood to return from the capillary beds to drain into the venous system via increasingly larger veins. Post-capillary venules are the smallest of the veins with a diameter of between 10 and 30 micrometres (μm). When the post-capillary venules increase in diameter to 50 μm they can incorporate smooth muscle and are known as muscular venules.[1] Veins contain approximately 70% of total blood volume, while about 25% is contained in the venules.[2] Many venules unite to form a vein.

Structure

[edit]This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (April 2018) |

Post-capillary venules have a single layer of endothelium surrounded by a basal lamina. Their size is between 10 and 30 micrometers and are too small to contain smooth muscle. They are instead supported by pericytes that wrap around them.[1] When the post-capillary venules increase in diameter to 50 μm they can incorporate smooth muscle and are known as muscular venules.[1] They have an inner endothelium composed of squamous endothelial cells that act as a membrane, a middle layer of muscle and elastic tissue and an outer layer of fibrous connective tissue. The middle layer is poorly developed so that venules have thinner walls than arterioles. They are porous so that fluid and blood cells can move easily from the bloodstream through their walls.

Short portal venules between the posterior pituitary and the anterior pituitary lobes provide an avenue for rapid hormonal exchange via the blood.[3] Specifically within and between the pituitary lobes is anatomical evidence for confluent interlobe venules providing blood from the anterior to the neural lobe that would facilitate moment-to-moment sharing of information between lobes of the pituitary gland.[3]

In contrast to regular venules, high endothelial venules are a special type of venule where the endothelium is made up of simple cuboidal cells. Lymphocytes exit the blood stream and enter the lymph nodes via these specialized venules when an infection is detected. Compared with arterioles, the venules are larger with much weaker muscular coat. They are the smallest united common branch in the human body.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Standring, Susan (2016). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (Forty-first ed.). [Philadelphia]. p. 131. ISBN 9780702052309.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Woods, Susan (2010). Cardiac Nursing. New York: Lippincotts. p. 955. ISBN 9780781792806.

- ^ a b Gross, PM; Joneja, MG; Pang, JJ; Polischuk, TM; Shaver, SW; Wainman, DS (1993). "Topography of short portal vessels in the rat pituitary gland: A scanning electron-microscopic and morphometric study of corrosion cast replicas". Cell and Tissue Research. 272 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1007/bf00323573. PMID 8481959. S2CID 23657199.