Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lymphocyte

View on Wikipedia

| Lymphocyte | |

|---|---|

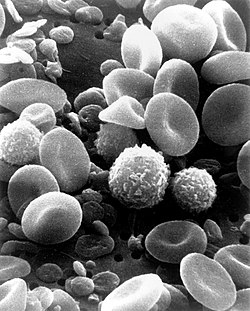

Scanning electron micrograph of a human T cell | |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system |

| Function | White blood cell |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D008214 |

| TH | H2.00.04.1.02002 |

| FMA | 84065 62863, 84065 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates.[1] Lymphocytes include T cells (for cell-mediated and cytotoxic adaptive immunity), B cells (for humoral, antibody-driven adaptive immunity),[2][3] and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs; "innate T cell-like" cells involved in mucosal immunity and homeostasis), of which natural killer cells are an important subtype (which functions in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity). They are the main type of cell found in lymph, which prompted the name "lymphocyte" (with cyte meaning cell).[4] Lymphocytes make up between 18% and 42% of circulating white blood cells.[2]

Types

[edit]

The three major types of lymphocyte are T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells.[2]

They can also be classified as small lymphocytes and large lymphocytes based on their size and appearance.[5][6]

Lymphocytes can be identified by their large nucleus.[citation needed]

T cells and B cells

[edit]T cells (thymus cells) and B cells (bone marrow- or bursa-derived cells[a]) are the major cellular components of the adaptive immune response. T cells are involved in cell-mediated immunity, whereas B cells are primarily responsible for humoral immunity (relating to antibodies). The function of T cells and B cells is to recognize specific "non-self" antigens, during a process known as antigen presentation. Once they have identified an invader, the cells generate specific responses that are tailored maximally to eliminate specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells. B cells respond to pathogens by producing large quantities of antibodies which then neutralize foreign objects like bacteria and viruses. In response to pathogens some T cells, called T helper cells, produce cytokines that direct the immune response, while other T cells, called cytotoxic T cells, produce toxic granules that contain powerful enzymes which induce the death of pathogen-infected cells. Following activation, B cells and T cells leave a lasting legacy of the antigens they have encountered, in the form of memory cells. Throughout the lifetime of an animal, these memory cells will "remember" each specific pathogen encountered, and are able to mount a strong and rapid response if the same pathogen is detected again; this is known as acquired immunity.[citation needed]

Natural killer cells

[edit]NK cells are a part of the innate immune system and play a major role in defending the host from tumors and virally infected cells.[2] NK cells modulate the functions of other cells, including macrophages and T cells,[2] and distinguish infected cells and tumors from normal and uninfected cells by recognizing changes of a surface molecule called major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I. NK cells are activated in response to a family of cytokines called interferons. Activated NK cells release cytotoxic (cell-killing) granules which then destroy the altered cells.[1] They are named "natural killer cells" because they do not require prior activation in order to kill cells which are missing MHC class I.[citation needed]

Dual expresser lymphocyte – X cell

[edit]The X lymphocyte is a reported cell type expressing both a B-cell receptor and T-cell receptor and is hypothesized to be implicated in type 1 diabetes.[8][9] Its existence as a cell type has been challenged by two studies.[10][11] However, the authors of original article pointed to the fact that the two studies have detected X cells by imaging microscopy and FACS as described.[12] Additional studies are required to determine the nature and properties of X cells (also called dual expressers).[citation needed]

Development

[edit]

Mammalian stem cells differentiate into several kinds of blood cell within the bone marrow.[13] This process is called haematopoiesis.[14] All lymphocytes originate, during this process, from a common lymphoid progenitor before differentiating into their distinct lymphocyte types. The differentiation of lymphocytes follows various pathways in a hierarchical fashion as well as in a more plastic fashion. The formation of lymphocytes is known as lymphopoiesis. In mammals, B cells mature in the bone marrow, which is at the core of most bones.[15] In birds, B cells mature in the bursa of Fabricius, a lymphoid organ where they were first discovered by Chang and Glick,[15] (B for bursa) and not from bone marrow as commonly believed. T cells migrate to the blood stream and mature in a distinct primary organ, called the thymus. Following maturation, the lymphocytes enter the circulation and peripheral lymphoid organs (e.g. the spleen and lymph nodes) where they survey for invading pathogens and/or tumor cells.

The lymphocytes involved in adaptive immunity (i.e. B and T cells) differentiate further after exposure to an antigen; they form effector and memory lymphocytes. Effector lymphocytes function to eliminate the antigen, either by releasing antibodies (in the case of B cells), cytotoxic granules (cytotoxic T cells) or by signaling to other cells of the immune system (helper T cells). Memory T cells remain in the peripheral tissues and circulation for an extended time ready to respond to the same antigen upon future exposure; they live weeks to several years, which is very long compared to other leukocytes.[citation needed]

Characteristics

[edit]

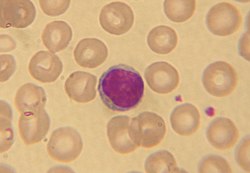

Microscopically, in a Wright's stained peripheral blood smear, a normal lymphocyte has a large, dark-staining nucleus with little to no eosinophilic cytoplasm. In normal situations, the coarse, dense nucleus of a lymphocyte is approximately the size of a red blood cell (about 7 μm in diameter).[13] Some lymphocytes show a clear perinuclear zone (or halo) around the nucleus or could exhibit a small clear zone to one side of the nucleus. Polyribosomes are a prominent feature in the lymphocytes and can be viewed with an electron microscope. The ribosomes are involved in protein synthesis, allowing the generation of large quantities of cytokines and immunoglobulins by these cells.[citation needed]

It is impossible to distinguish between T cells and B cells in a peripheral blood smear.[13] Normally, flow cytometry testing is used for specific lymphocyte population counts. This can be used to determine the percentage of lymphocytes that contain a particular combination of specific cell surface proteins, such as immunoglobulins or cluster of differentiation (CD) markers or that produce particular proteins (for example, cytokines using intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS)). In order to study the function of a lymphocyte by virtue of the proteins it generates, other scientific techniques like the ELISPOT or secretion assay techniques can be used.[1]

Typical recognition markers for lymphocytes[16] Class Function Proportion (median, 95% CI) Phenotypic marker(s) Natural killer cells Lysis of virally infected cells and tumour cells 7% (2–13%) CD16 CD56 but not CD3 T helper cells Release cytokines and growth factors that regulate other immune cells 46% (28–59%) TCRαβ, CD3 and CD4 Cytotoxic T cells Lysis of virally infected cells, tumour cells and allografts 19% (13–32%) TCRαβ, CD3 and CD8 Gamma delta T cells Immunoregulation and cytotoxicity 5% (2–8%) TCRγδ and CD3 B cells Secretion of antibodies 23% (18–47%) MHC class II, CD19 and CD20

In the circulatory system, they move from lymph node to lymph node.[3][17] This contrasts with macrophages, which are rather stationary in the nodes.

Lymphocytes and disease

[edit]

A lymphocyte count is usually part of a peripheral complete blood cell count and is expressed as the percentage of lymphocytes to the total number of white blood cells counted.[citation needed]

A general increase in the number of lymphocytes is known as lymphocytosis,[18] whereas a decrease is known as lymphocytopenia.

High

[edit]An increase in lymphocyte concentration is usually a sign of a viral infection (in some rare cases, leukemias are found through an abnormally raised lymphocyte count in an otherwise normal person).[18][19] A high lymphocyte count with a low neutrophil count might be caused by lymphoma. Pertussis toxin (PTx) of Bordetella pertussis, formerly known as lymphocytosis-promoting factor, causes a decrease in the entry of lymphocytes into lymph nodes, which can lead to a condition known as lymphocytosis, with a complete lymphocyte count of over 4000 per μl in adults or over 8000 per μl in children. This is unique in that many bacterial infections illustrate neutrophil-predominance instead.[citation needed]

Lymphoproliferative disorders

[edit]Lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) encompass a diverse group of diseases marked by uncontrolled lymphocyte production, leading to issues like lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and bone marrow infiltration. These disorders are common in immunocompromised individuals and involve abnormal proliferation of T and B cells, often resulting in immunodeficiency and immune system dysfunction. Various gene mutations, both iatrogenic and acquired, are implicated in LPD. One subtype, X-linked LPD, is linked to mutations in the X chromosome, predisposing individuals to natural killer cell LPD and T-cell LPD. Additionally, conditions like common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), and certain viral infections elevate the risk of LPD. Treatment methods, such as immunosuppressive drugs and tissue transplantation, can also increase susceptibility. LPDs encompass a wide array of disorders involving B-cell (e.g., chronic lymphocytic leukemia) and T-cell (e.g., Sezary syndrome) abnormalities, each presenting distinct challenges in diagnosis and management.[20]

Low

[edit]A low normal to low absolute lymphocyte concentration is associated with increased rates of infection after surgery or trauma.[21]

One basis for low T cell lymphocytes occurs when the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects and destroys T cells (specifically, the CD4+ subgroup of T lymphocytes, which become helper T cells).[22] Without the key defense that these T cells provide, the body becomes susceptible to opportunistic infections that otherwise would not affect healthy people. The extent of HIV progression is typically determined by measuring the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the patient's blood – HIV ultimately progresses to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The effects of other viruses or lymphocyte disorders can also often be estimated by counting the numbers of lymphocytes present in the blood.[citation needed]

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

[edit]In some cancers, such as melanoma and colorectal cancer, lymphocytes can migrate into and attack the tumor. This can sometimes lead to regression of the primary tumor.[citation needed]

Lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia

[edit]Blood content

[edit]

History

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The process of B-cell maturation was elucidated in birds and the B most likely means "bursa-derived" referring to the bursa of Fabricius.[7] However, in humans (who do not have that organ), the bone marrow makes B cells, and the B can serve as a reminder of bone marrow.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M (2001). Immunobiology (5th ed.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-4101-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e Omman, Reeba A.; Kini, Ameet R. (2020). "Leukocyte development, kinetics, and functions". In Keohane, Elaine M.; Otto, Catherine N.; Walenga, Jeanine N. (eds.). Rodak's Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications (6th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. pp. 117–135. ISBN 978-0-323-53045-3.

- ^ a b Cohn, Lauren; Hawrylowicz, Catherine; Ray, Anuradha (2014). "Biology of Lymphocytes". Middleton's Allergy. pp. 203–214. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-08593-9.00013-9. ISBN 978-0-323-08593-9.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

A type of immune cell that is made in the bone marrow and is found in the blood and in lymph tissue. The two main types of lymphocytes are B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes. B lymphocytes make antibodies, and T lymphocytes help kill tumor cells and help control immune responses. A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell.

- ^ van der Meer, Wim; van Gelder, Warry; de Keijzer, Ries; Willems, Hans (July 2007). "The divergent morphological classification of variant lymphocytes in blood smears". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 60 (7): 838–839. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.033787. PMC 1995771. PMID 17596551.

- ^ Lewis, Dorothy E.; Harriman, Gregory R.; Blutt, Sarah E. (2013). "Organization of the immune system". Clinical Immunology. pp. 16–34. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7234-3691-1.00026-X. ISBN 978-0-7234-3691-1.

Small lymphocytes range between 7 and 10 μm in diameter.

- ^ "B Cell". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Ahmed, Rizwan; Omidian, Zahra; Giwa, Adebola; Cornwell, Benjamin; Majety, Neha; Bell, David R.; Lee, Sangyun; Zhang, Hao; Michels, Aaron; Desiderio, Stephen; Sadegh-Nasseri, Scheherazade; Rabb, Hamid; Gritsch, Simon; Suva, Mario L.; Cahan, Patrick; Zhou, Ruhong; Jie, Chunfa; Donner, Thomas; Hamad, Abdel Rahim A. (May 2019). "A Public BCR Present in a Unique Dual-Receptor-Expressing Lymphocyte from Type 1 Diabetes Patients Encodes a Potent T Cell Autoantigen". Cell. 177 (6): 1583–1599.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.007. PMC 7962621. PMID 31150624.

- ^ "Newly Discovered Immune Cell Linked to Type 1 Diabetes" (Press release). Johns Hopkins Medicine. 30 May 2019.

- ^ Japp, Alberto (4 February 2021). "TCR+/BCR+ dual-expressing cells and their associated public BCR clonotype are not enriched in type 1 diabetes". Cell. 184 (3): 827–839. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.035. PMC 8016147. PMID 33545036.

- ^ Burel, Julie (13 May 2020). "The Challenge of Distinguishing Cell–Cell Complexes from Singlet Cells in Non-Imaging Flow Cytometry and Single-Cell Sorting". Cytometry Part A. 97 (11): 1127–1135. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.24027. PMC 7666012. PMID 32400942.

- ^ Ahmed, Rizwan; Omidian, Zahra; Giwa, Adebola; Donner, Thomas; Jie, Chunfa; Hamad, Abdel Rahim A. (February 2021). "A reply to 'TCR+/BCR+ dual-expressing cells and their associated public BCR clonotype are not enriched in type 1 diabetes'". Cell. 184 (3): 840–843. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.036. PMC 7935028. PMID 33545037.

- ^ a b c Abbas AK, Lichtman AH (2003). Cellular and Molecular Immunology (5th ed.). Saunders, Philadelphia. ISBN 0-7216-0008-5.[page needed]

- ^ Monga I, Kaur K, Dhanda S (March 2022). "Revisiting hematopoiesis: applications of the bulk and single-cell transcriptomics dissecting transcriptional heterogeneity in hematopoietic stem cells". Briefings in Functional Genomics. 21 (3): 159–176. doi:10.1093/bfgp/elac002. PMID 35265979.

- ^ a b Cooper MD (March 2015). "The early history of B cells". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 15 (3): 191–197. doi:10.1038/nri3801. PMID 25656707.

- ^ Berrington JE, Barge D, Fenton AC, Cant AJ, Spickett GP (May 2005). "Lymphocyte subsets in term and significantly preterm UK infants in the first year of life analysed by single platform flow cytometry". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 140 (2): 289–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02767.x. PMC 1809375. PMID 15807853.

- ^ Al-Shura, Anika Niambi (2020). "Lymphocytes". Advanced Hematology in Integrated Cardiovascular Chinese Medicine. pp. 41–46. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-817572-9.00007-0. ISBN 978-0-12-817572-9.

- ^ a b "Lymphocytosis: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Guilbert, Theresa W.; Gern, James E.; Lemanske, Robert F. (2010). "Infections and Asthma". Pediatric Allergy: Principles and Practice. pp. 363–376. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4377-0271-2.00035-3. ISBN 978-1-4377-0271-2. PMC 7173498.

Lymphocytes are recruited into the upper and lower airways during the early stages of a viral respiratory infection, and it is presumed that these cells help to limit the extent of infection and to clear virus-infected epithelial cells.

- ^ Justiz Vaillant, Angel A.; Stang, Christopher M. (2023), "Lymphoproliferative Disorders", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725847, retrieved 7 October 2023

- ^ Clumeck, Nathan; de Wit, Stéphane (2010). "Prevention of opportunistic infections" (PDF). Infectious Diseases. pp. 958–963. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-04579-7.00090-3. ISBN 978-0-323-04579-7.

- ^ Wahed, Amer; Quesada, Andres; Dasgupta, Amitava (2020). "Benign white blood cell and platelet disorders". Hematology and Coagulation. pp. 77–87. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814964-5.00005-x. ISBN 978-0-12-814964-5.

Lymphocytopenia may also be acquired, for example, in patients with HIV infection.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 01701ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- "Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte". Cell Centered Database.

- "Overcoming the Rejection Factor: MUSC's First Organ Transplant". Waring Historical Library.

Lymphocyte

View on GrokipediaTypes

T cells

T cells, also known as T lymphocytes, are a major subset of lymphocytes essential for cell-mediated adaptive immunity, comprising 60–85% of circulating lymphocytes.[8] These cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and migrate to the thymus for maturation, where they undergo rigorous selection processes to ensure functionality and self-tolerance.[9] T cells are distinguished by the presence of a T cell receptor (TCR) on their surface, which enables antigen-specific recognition, and they play pivotal roles in coordinating immune responses against intracellular pathogens, tumors, and in maintaining immune homeostasis.[10] T cells differentiate into several subtypes based on surface markers and functions, including CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and memory T cells. CD4+ helper T cells, often referred to as Th cells, assist in activating other immune cells by secreting cytokines and are subdivided into functional classes such as Th1, Th2, Th17, and Tfh based on their cytokine profiles and roles in directing immune responses.[11] CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directly eliminate infected or malignant cells through granule-mediated apoptosis.[12] Regulatory T cells, characterized by high expression of Foxp3 and CD25, suppress excessive immune responses to prevent autoimmunity and maintain tolerance, comprising 5-10% of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood.[6] Memory T cells, which arise from activated naive T cells, provide long-term immunity by rapidly responding to previously encountered antigens and persisting for decades in lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues.[13] The development of T cells occurs primarily in the thymus through a multi-stage process involving positive and negative selection to generate a repertoire capable of recognizing foreign antigens while avoiding self-reactivity. Immature T cell precursors, known as thymocytes, progress from double-negative (CD4- CD8-) to double-positive (CD4+ CD8+) stages, where they rearrange TCR genes to create diverse specificities.[14] Positive selection ensures survival of thymocytes whose TCRs can weakly bind self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on cortical thymic epithelial cells, committing them to either CD4+ or CD8+ lineages based on MHC class II or I recognition, respectively; this process rescues about 5-10% of thymocytes from programmed cell death.[15] Negative selection in the thymic medulla deletes thymocytes with high-affinity TCR binding to self-peptide-MHC complexes presented by dendritic cells or medullary thymic epithelial cells, thereby establishing central tolerance and eliminating potentially autoreactive clones.[15] Surviving single-positive T cells exit the thymus as naive T cells, entering circulation to patrol secondary lymphoid organs.[9] Activation of naive T cells requires two signals: antigen-specific recognition and co-stimulation, ensuring responses are targeted and prevent anergy or tolerance induction. The TCR, often paired with CD3 and CD4 or CD8 co-receptors, binds to peptide antigens presented by MHC molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), triggering intracellular signaling cascades that initiate proliferation and differentiation.[16] Co-stimulation via CD28 binding to B7 ligands (CD80/CD86) on APCs is essential for full activation, promoting cytokine production, survival, and metabolic reprogramming; without it, T cells become unresponsive.[10] Cytokine signaling, such as IL-2 from activated T cells binding to its receptor, further amplifies proliferation and effector differentiation in an autocrine and paracrine manner.[17] Upon activation, T cells execute diverse effector functions tailored to their subtype, contributing to pathogen clearance and immune regulation. Helper T cells (CD4+) release cytokines like IL-2 to promote T cell growth and IFN-γ to activate macrophages for intracellular killing, with Th1 cells particularly emphasizing IFN-γ production to combat viral and bacterial infections.[17] Cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) induce target cell death by releasing perforin, which forms pores in the plasma membrane, allowing granzymes to enter and activate caspases for apoptosis; this mechanism is critical for eliminating virally infected cells and tumor targets.[12] Regulatory T cells exert suppressive functions through mechanisms including cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β), direct cell-cell contact via CTLA-4, and metabolic disruption of effector T cells, thereby dampening inflammation and preventing autoimmunity.[18] Memory T cells, including central and effector memory subsets, maintain surveillance and mount accelerated responses upon re-encountering antigens, ensuring durable protection without the need for primary activation.[13]B cells

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow, where they undergo a series of maturation stages characterized by V(D)J recombination to generate diverse B cell receptors (BCRs).[19] This process begins at the pro-B cell stage with the rearrangement of D and J segments of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus, followed by V to DJ joining, and subsequently light chain rearrangements, enabling the production of a vast repertoire of antigen-specific BCRs essential for recognizing diverse pathogens.[20] Immature B cells expressing functional BCRs then undergo negative selection to eliminate self-reactive clones before maturing and migrating to peripheral lymphoid tissues.[21] B cells constitute approximately 10-20% of circulating lymphocytes in human peripheral blood.[22] Activation of mature naive B cells primarily occurs upon antigen binding to the BCR, which triggers intracellular signaling cascades leading to initial proliferation and survival signals.[23] For most antigens, full activation requires additional help from T helper cells, involving interactions such as CD40 ligand (CD40L) on T cells binding to CD40 on B cells, along with cytokine secretion that promotes B cell expansion and differentiation.[24] These T cell-dependent pathways are crucial in secondary lymphoid organs like germinal centers, where activated B cells interact with follicular helper T cells to refine their responses.[25] Upon activation, B cells differentiate into two main effector lineages: plasma cells and memory B cells. Plasma cells, which are terminally differentiated and non-dividing, migrate to survival niches in the bone marrow and secrete large quantities of antibodies, including isotypes such as IgM (initial response), IgG (long-term systemic immunity), IgA (mucosal protection), IgE (allergic and parasitic responses), and IgD (regulatory roles on naive B cells).[26] Memory B cells, in contrast, persist long-term in lymphoid tissues and circulation, providing rapid and enhanced responses upon re-exposure to the same antigen through pre-existing high-affinity BCRs.[27] During this differentiation in germinal centers, somatic hypermutation introduces point mutations into the variable regions of BCR genes, facilitating affinity maturation where B cells with higher antigen-binding affinity are preferentially selected.[28] The primary function of B cells in humoral immunity involves antibody production that mediates pathogen clearance through several mechanisms. Antibodies facilitate opsonization by coating pathogens to enhance phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils.[29] They also activate the complement system via the classical pathway, leading to pathogen lysis or further opsonization through C3b deposition.[29] Neutralization occurs when antibodies bind to viral or toxin epitopes, preventing host cell infection or tissue damage.[27] In mucosal immunity, IgA secreted by plasma cells at epithelial surfaces forms dimers that agglutinate pathogens and block adherence to mucosal linings, providing a first line of defense at sites like the gut and respiratory tract.[30]Natural killer cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are a subset of lymphocytes that originate from common lymphoid progenitors in the bone marrow, developing independently of the thymus.[31] Unlike T cells, they do not require thymic maturation and lack antigen-specific receptors such as T cell receptors (TCR) or B cell receptors (BCR).[32] In human peripheral blood, NK cells constitute approximately 5-15% of total lymphocytes and are identified by the absence of CD3 expression combined with positivity for CD56 and often CD16 surface markers (CD3⁻ CD56⁺ CD16⁺).[33][34] NK cells are activated through two primary mechanisms: missing-self recognition, where they detect and respond to cells with reduced or absent major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), mediated by Fcγ receptors such as CD16 that bind to antibody-coated targets.[35][36] The missing-self hypothesis posits that inhibitory receptors on NK cells, including killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), engage self-MHC class I molecules to maintain tolerance to healthy cells; downregulation of MHC class I on virally infected or tumor cells relieves this inhibition, triggering NK cell activation.[35] In ADCC, NK cells recognize IgG antibodies bound to target cells via CD16, leading to targeted lysis without requiring prior antigen-specific priming.[36] Upon activation, NK cells exert their effector functions primarily through the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes, which induce apoptosis in target cells by forming pores in the plasma membrane and activating intracellular caspases, respectively.[37] Additionally, they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which amplify immune responses by activating macrophages, enhancing antigen presentation, and promoting T cell differentiation.[37] These mechanisms position NK cells as key innate effectors against viral infections and malignancies, providing rapid cytotoxicity without the need for adaptive immune involvement.[37] Human NK cells are heterogeneous and can be divided into two main subpopulations based on CD56 expression levels: CD56bright and CD56dim.[34] The CD56bright subset, which comprises about 10% of circulating NK cells, is characterized by high cytokine production (e.g., IFN-γ) and low cytotoxic potential in the resting state, playing a regulatory role in immune modulation.[34] In contrast, the CD56dim subset, making up 90% of NK cells, expresses high levels of CD16 and perforin, enabling potent direct cytotoxicity and ADCC against infected or transformed cells.[34] This functional dichotomy allows NK cells to balance immediate killing with broader immunomodulatory effects.[34]Rare and emerging types

Gamma delta (γδ) T cells represent a distinct subset of T lymphocytes that bridge innate and adaptive immunity through their unique T cell receptor (TCR) composed of γ and δ chains rather than the conventional α and β chains.[38] These cells recognize stress-induced ligands, such as phosphoantigens or non-peptide molecules expressed on infected or transformed cells, without requiring major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation, enabling rapid responses akin to innate immunity while retaining adaptive potential through clonal expansion.[39] Constituting 1-10% of circulating T cells in humans but enriched in mucosal tissues like the skin and gut, γδ T cells contribute to early defense against pathogens and tumor surveillance by producing cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-17 (IL-17).[40] Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a family of non-B, non-T lymphocytes that lack antigen-specific receptors and are primarily tissue-resident, playing key roles in maintaining homeostasis and orchestrating immune responses at mucosal barriers.[41] ILCs are classified into three main subsets—ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3—based on their transcriptional regulators and cytokine profiles, mirroring T helper cell functions: ILC1 produce IFN-γ for antiviral and antitumor defense, ILC2 secrete type 2 cytokines like IL-5 and IL-13 to combat parasites and promote allergic responses, and ILC3 generate IL-17 and IL-22 to support antibacterial immunity and epithelial integrity.[42] Collectively, ILCs comprise less than 1% of total lymphocytes in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissues but are more abundant in mucosa, where they rapidly respond to environmental cues to preserve barrier function.[43] Emerging research highlights ILCs' involvement in gut barrier maintenance, where ILC3-derived IL-22 promotes antimicrobial peptide production and epithelial repair, preventing dysbiosis and pathogen invasion.[44] Post-2020 studies have further linked ILC dysregulation to neuroinflammation, with ILC2 and ILC3 infiltrating the central nervous system in models of multiple sclerosis and contributing to cytokine-driven pathology via IL-17 and IL-22 signaling.[45] Dual expresser lymphocytes, often termed X cells and characterized by co-expression of T cell (CD3+) and natural killer (NK) cell (CD56+) markers, form a rare population identified primarily in mucosal sites such as tonsils and intestines.[46] First described in the 2010s, these CD3+CD56+ cells exhibit hybrid features, combining TCR-mediated antigen recognition with NK-like cytotoxicity and cytokine production, potentially enhancing mucosal immunity against infections and tumors.[47] Representing a minor fraction of lymphocytes, X cells express gut-homing integrins and respond to mucosal signals, suggesting specialized roles in local immune surveillance without full commitment to classical T or NK lineages.[46]Origin and Development

Hematopoietic origin

Lymphocytes originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) residing in the bone marrow, where they undergo a series of differentiation steps to commit to the lymphoid lineage. HSCs first give rise to multipotent progenitors (MPPs), which then progress to common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), a population characterized by markers such as IL-7Rα⁺, Lin⁻, Sca-1^{low}, and c-Kit^{low}. These CLPs represent a committed stage capable of generating all lymphoid cells, including B cells, T cell precursors, and natural killer (NK) cells, without significant myeloid potential.[48]81722-X) The commitment to the lymphoid lineage is orchestrated by key transcription factors, notably Ikaros and PU.1. Ikaros, a zinc finger DNA-binding protein, is essential for the earliest stages of lymphoid specification, promoting the expression of genes required for lymphocyte development while repressing alternative myeloid fates; its absence severely impairs lymphopoiesis. PU.1, an ETS family transcription factor, plays a dosage-dependent role in balancing myeloid and lymphoid differentiation, with intermediate levels favoring lymphoid commitment in early progenitors. Additional stages include early lymphoid progenitors (ELPs), identified as Flt3^{hi} VCAM-1⁻ MPPs, which exhibit a lymphoid-biased potential prior to full CLP formation.90337-0)[48] Cytokines such as interleukin-7 (IL-7) are critical for the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of lymphoid progenitors. IL-7 signaling through its receptor supports CLP maintenance and early B and T lineage expansion, with deficiencies leading to profound lymphopenia. In adults, the bone marrow serves as the primary site of lymphocyte production, while during fetal development, the liver also contributes significantly to HSC-derived lymphopoiesis. Approximately 10^9 new lymphocytes are produced daily in the human bone marrow to sustain immune homeostasis.[49]Maturation and migration

Lymphocytes undergo organ-specific maturation processes following their commitment from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. B cells mature primarily in the bone marrow, progressing through defined stages to generate functional, self-tolerant cells. Pro-B cells initiate heavy chain gene rearrangement, forming D-J and then V-DJ segments, without surface immunoglobulin expression.[50] Pre-B cells achieve successful μ heavy chain rearrangement, pairing it with surrogate light chains to form the pre-B cell receptor, which signals proliferation and light chain rearrangement.[50] Immature B cells express surface IgM after light chain completion and undergo central tolerance checks, where autoreactive cells are eliminated or undergo receptor editing—a secondary light chain rearrangement to alter specificity and promote self-tolerance.[50] T cells migrate to the thymus for maturation, where thymocytes advance from double-negative (CD4⁻ CD8⁻) stages, subdivided by CD44 and CD25 expression, to double-positive (CD4⁺ CD8⁺) cells after β-selection ensures productive T cell receptor (TCR) β-chain rearrangement.[51] In the double-positive stage, α-chain rearrangement occurs, followed by positive selection in the thymic cortex for cells with moderate self-MHC affinity and negative selection in the medulla to delete strongly self-reactive clones, eliminating over 90% of thymocytes through apoptosis during central tolerance.[51][52] Surviving single-positive naïve T cells (CD4⁺ or CD8⁺) emigrate from the thymus to enter circulation.[51] Natural killer (NK) cells develop mainly in the bone marrow from common lymphoid progenitors, acquiring the IL-15 receptor (CD122) for survival and maturation, with immature forms predominating before egress via sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 5 (S1P5) and CX3CR1.[53] Maturation continues in secondary lymphoid tissues like lymph nodes, where human CD56^{bright} NK cells home via CCR7.[53] Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), including ILC2s, develop precursors in the bone marrow but mature in peripheral tissues such as the gut, where they regulate homeostasis and respond to helminths.[53] Mature naïve lymphocytes recirculate via blood and lymph, guided by chemokines for homing to lymphoid organs. B and T cells enter lymph nodes and spleen through high endothelial venules, dependent on CCR7 binding CCL19/CCL21 for initial tethering and CXCL12 signaling via CXCR4 for retention and further migration.[54] Mucosal homing to sites like Peyer's patches additionally requires CXCR5 for CXCL13-guided entry into follicles.[54] NK cells and ILCs localize to tissues via CX3CR1 and tissue-specific cues, supporting barrier immunity.[53]Structure and Characteristics

Morphological features

Lymphocytes exhibit distinct morphological features that vary by size and activation state, observable under light and electron microscopy. Small lymphocytes, the most common circulating form, measure 7-10 μm in diameter and display a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N:C) ratio of approximately 4:1 to 5:1, with scant, pale blue cytoplasm surrounding a large, spherical nucleus containing densely condensed chromatin.[55][56] This compact structure reflects their resting state, with minimal visible organelles under light microscopy.[1] Large lymphocytes, including activated forms and natural killer (NK) cells, range from 10-15 μm in diameter and possess a lower N:C ratio of about 2:1 to 3:1, featuring more abundant cytoplasm that may contain azurophilic granules, particularly in NK cells.[55][5] These granules appear as fine to coarse red-purple inclusions under light microscopy, distinguishing NK cells from other agranular lymphocytes.[57] Under electron microscopy, resting small lymphocytes show sparse cytoplasm with few organelles, including scattered mitochondria, a small Golgi apparatus, and limited rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER).[58] In activated lymphocytes or plasma cell precursors, ultrastructure reveals expanded rough ER and prominent Golgi complexes, facilitating protein synthesis and secretion.[58] In tissues, lymphocytes cluster within lymphoid follicles of secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and spleen, where B cells predominate in germinal centers—pale-staining regions rich in proliferating cells.[59][60] T cells are more diffusely distributed in paracortical areas surrounding these follicles.[59] In Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears, most lymphocytes appear agranular with round nuclei and minimal cytoplasm, except for NK cells, which display characteristic azurophilic granules.[5] During infections like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced mononucleosis, atypical forms known as Downey cells emerge—enlarged lymphocytes with abundant basophilic cytoplasm, indented nuclei, and irregular chromatin, often comprising over 10% of circulating cells.[61]32962-9/fulltext)Surface markers and identification

Lymphocytes are primarily identified through their expression of specific surface markers, which are proteins detected using immunological techniques to distinguish them from other leukocytes and to subtype them further. The pan-leukocyte marker CD45, also known as the leukocyte common antigen, is brightly expressed on all lymphocytes and serves as a foundational identifier in flow cytometry to gate the lymphocyte population based on low forward and side scatter properties.[62] For T cells, the CD3 complex is a universal surface marker that defines all mature T lymphocytes, while CD4 and CD8 distinguish helper and cytotoxic subsets, respectively, enabling precise enumeration of these populations in peripheral blood. B cells are characterized by CD19 and CD20, which are pan-B cell markers, along with surface immunoglobulin (sIg) that reflects their antigen-binding capability, though sIg expression can vary in maturity and disease states. Natural killer (NK) cells lack CD3 but express CD16 (FcγRIII, involved in antibody-dependent cytotoxicity) and CD56 (neural cell adhesion molecule), with CD56^bright and CD56^dim subsets indicating functional differences in cytokine production and killing efficiency.[62][63] Activation of lymphocytes is marked by upregulation of specific receptors and molecules detectable on the cell surface. Early activation is indicated by CD69, a C-type lectin receptor expressed within hours of stimulation, while CD25 (the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor) signifies progression to proliferation and cytokine responsiveness; late activation involves HLA-DR, a class II MHC molecule that enhances antigen presentation. These markers allow tracking of immune responses in real-time.[62][63] Subsets within lymphocyte types are further delineated by isoform-specific markers, such as CD45RA on naive T cells, which have not encountered antigen, contrasting with CD45RO on memory T cells that have undergone differentiation and clonal expansion. In chronic infections or cancer, PD-1 (programmed death-1) emerges as a key marker of T cell exhaustion, where its expression on tumor-specific or persistently stimulated T cells correlates with impaired effector functions and immune evasion.[62][64] Identification of lymphocytes relies on techniques that exploit these surface markers for high-throughput analysis. Immunofluorescence microscopy uses fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to visualize markers on fixed cells, providing qualitative confirmation, while fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), a form of flow cytometry, enables multiparametric analysis of up to 17 colors simultaneously to quantify rare subsets and assess co-expression patterns. Automated hematology analyzers complement this by providing absolute lymphocyte counts through impedance or optical methods in routine complete blood counts, though they lack subtype specificity without additional flow cytometry. Morphological features, such as the high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio in lymphocytes, aid initial visual gating in flow cytometry scatter plots.[62][65][66]Functions

Role in adaptive immunity

Lymphocytes, particularly T cells and B cells, are central to adaptive immunity, which provides antigen-specific defense through recognition, amplification, and long-term memory. Naive T cells and B cells circulate until they encounter their specific antigen, triggering a coordinated response that distinguishes self from non-self and mounts targeted attacks on pathogens. This process begins with antigen presentation by professional antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, which capture microbial antigens and migrate to lymphoid organs to display them via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules to naive CD4+ helper T cells. Upon recognition, these T cells undergo clonal expansion, proliferating into effector subsets that amplify the response, typically peaking 7-10 days after initial exposure.[2] T-B cell collaboration is essential for humoral immunity, where activated CD4+ T helper cells provide critical signals to B cells in secondary lymphoid tissues. In germinal centers, B cells present processed antigens to T cells via MHC class II, receiving CD40 ligand and cytokine support in return, which drives B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation for affinity maturation, and class-switch recombination for isotype switching from IgM to IgG or other effectors. This interaction refines antibody production, enhancing pathogen neutralization and opsonization. The innate immune system primes this adaptive phase by delivering initial inflammatory cues that activate dendritic cells.[67] Adaptive immunity establishes immunological memory through long-lived memory T and B cells, which persist for decades and enable faster, more robust secondary responses upon re-exposure. These memory cells, generated during primary responses in germinal centers and lymphoid tissues, express high-affinity receptors and rapidly differentiate into effectors, reducing disease severity or preventing infection altogether. Vaccination exploits this mechanism; for instance, the measles vaccine induces lifelong T and B memory cells, conferring durable protection against the virus.[2][68] To prevent autoimmunity, adaptive responses incorporate tolerance mechanisms that eliminate or suppress self-reactive lymphocytes. Central tolerance deletes autoreactive T cells in the thymus and B cells in the bone marrow via apoptosis, while peripheral tolerance induces anergy in T cells lacking costimulatory signals or in B cells with low-affinity self-antigen binding. Regulatory T cells (Tregs), a subset of CD4+ T cells, further maintain tolerance by secreting suppressive cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β to inhibit autoreactive responses. These layered controls ensure adaptive immunity targets foreign threats without harming host tissues.[69]Role in innate immunity

Natural killer (NK) cells serve as a critical component of innate immunity by rapidly surveilling and eliminating virus-infected or stressed cells, primarily through recognition of stress-induced ligands such as those binding to the activating receptor NKG2D.[70] Upon engagement of NKG2D with its ligands, like MICA or MICB expressed on infected cells, NK cells trigger cytotoxic granule release and cytokine production, enabling direct lysis of targets within hours of infection onset.[71] Additionally, NK cells can develop memory-like features after initial stimulation by certain pathogens, haptens, or cytokines, leading to enhanced functional responses upon re-exposure.[72] This germline-encoded mechanism provides immediate defense against pathogens and, in certain contexts, enables memory-like enhanced responses upon re-exposure, primarily contrasting with the antigen-specific nature of adaptive responses that develop over days.[73] Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) further bolster innate immunity at mucosal barriers, with distinct subsets tailored to specific threats. ILC1s, akin to NK cells in function, produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ) to combat intracellular pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, promoting macrophage activation and restricting microbial replication in tissues like the liver and intestine.[74] ILC2s drive type 2 immune responses against helminths and allergens by secreting IL-5 and IL-13, which recruit and activate eosinophils to enhance barrier defense and tissue repair, though this can exacerbate allergic conditions.[75] In the lungs, ILC2s are particularly vital, where their activation in response to epithelial alarmins like IL-33 sustains airway homeostasis but contributes to eosinophilic inflammation in asthma.[76] ILC3s maintain gut microbiota balance through IL-22 production, which strengthens epithelial barriers, induces antimicrobial peptides, and prevents bacterial translocation, thereby controlling commensal communities and early infections.[77] NK cells and ILCs also bridge innate and adaptive immunity by modulating antigen-presenting cells and amplifying humoral responses. NK-derived cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, promote dendritic cell (DC) maturation, enhancing their ability to prime T cells for subsequent adaptive responses.[78] Additionally, NK cells mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) via CD16 (FcγRIII), where they lyse antibody-coated targets, thereby potentiating innate control of pathogens and early antibody effects.[79] Post-2020 studies have underscored ILC involvement in viral outcomes, revealing that expanded ILC2 populations expressing NKG2D correlate with severe COVID-19, linking dysregulated innate responses to exacerbated inflammation.[80]Clinical Significance

Normal levels and measurement

In healthy adults, the normal absolute lymphocyte count in peripheral blood typically ranges from 1,000 to 4,800 cells per microliter (μL), representing approximately 20% to 40% of total white blood cells.[81][82] In children, these counts are generally higher, ranging from 3,000 to 9,500 cells per μL, with percentages often between 20% and 50% of white blood cells, varying by age group due to ongoing immune system development.[81][83] Among circulating lymphocytes, T cells (CD3+) constitute 60% to 80%, B cells (CD19+ or CD20+) 10% to 20%, and natural killer (NK) cells (CD56+) 5% to 15% in adults.[84][85] These distributions vary in tissues; for example, the spleen contains a higher proportion of B cells (up to 50-60% of lymphocytes in the white pulp) compared to peripheral blood, reflecting its role in B cell maturation and antibody production.[86] Similarly, bone marrow has elevated levels of B cell precursors and plasma cells.[87] Lymphocyte levels are commonly measured via complete blood count (CBC) with differential, which provides absolute and relative counts from a standard blood sample.[81] For detailed subset analysis, flow cytometry is used, employing fluorescent antibodies to identify cell surface markers like CD3, CD19, and CD56 on individual cells passing through a laser beam.[62][88] Tissue lymphocyte composition, such as in lymph nodes, is assessed through biopsy, followed by histopathological examination or flow cytometry on dissociated cells.[89] Reference ranges for lymphocyte counts are established by organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and clinical laboratories, often adjusted for age and sex, with adult ranges derived from large population studies showing 1.0 to 4.8 × 10^9/L.[90] Factors influencing normal levels include age (higher in infancy and declining with maturity), ethnicity (e.g., slightly lower counts in some African populations), and circadian rhythms (peaking in the early morning due to hormonal and trafficking variations).[91][92] Acute exercise can transiently elevate circulating lymphocyte counts by 50-200% immediately post-activity, driven by catecholamine release and increased blood flow, before returning to baseline within hours.[93][94]| Parameter | Adult Range (per μL) | Child Range (per μL) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Lymphocyte Count | 1,000–4,800 | 3,000–9,500 | Higher in children; 20–40% of WBCs in adults, 20–50% in children[81] |

| T Cells (% of lymphocytes) | 60–80% | Similar, age-adjusted | CD3+ marker[84] |

| B Cells (% of lymphocytes) | 10–20% | 10–30% | Higher in spleen (50–60%)[85][86] |

| NK Cells (% of lymphocytes) | 5–15% | 5–20% | CD56+ marker[84] |