Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

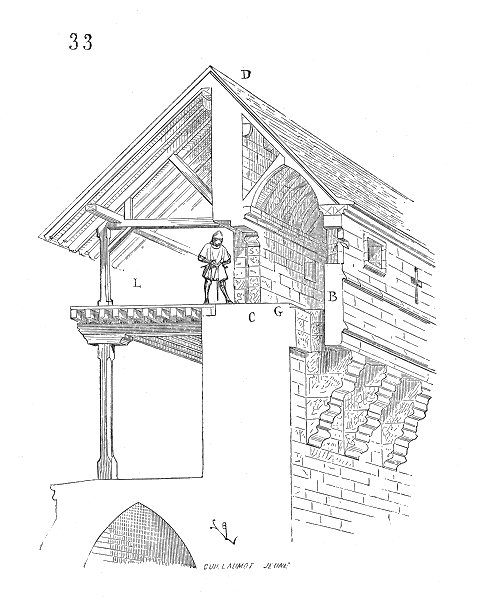

Machicolation

View on WikipediaIn architecture, a machicolation (French: mâchicoulis) is an opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement through which defenders could target attackers who had reached the base of the defensive wall. A smaller related structure that only protects key points of a fortification are referred to as Bretèche. Machicolation, hoarding, bretèche, and murder holes are all similar defensive features serving the same purpose, that is to enable defenders atop a defensive structure to target attackers below. The primary benefit of the design allowed defenders to remain behind cover rather than being exposed when leaning over the parapet. They were common in defensive fortifications until the widespread adoption of gunpowder weapons made them obsolete.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]The word machicolation derives from Old French machecol, mentioned in Medieval Latin as machecollum, probably from Old French machier 'crush', 'wound' and col 'neck'.[1] The verb Machicolate is first recorded in English in the 18th century, but machicollāre is attested in Anglo-Latin.[2][page needed]

Origins and Regional Prevalence

[edit]

The oldest known buildings with machicolation are Ancient Roman fortifications of the Limes Arabicus, such as Qasr Bshir and Qasr al-Hallabat, dating from the 4th century AD.[3] The design was brought to Europe from the Levant following the crusades and became especially prevalent in Southern Europe.

Machicolations were more common in French castles than English, where they are usually restricted to the gateway, as in the 13th-century Conwy Castle.[4] Within France, machicolation is more common on southern castles. One of the oldest extant examples of machicolation in northern France is at Château de Farcheville which was built from 1290 to 1304.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Greimas (1987). A.-J; Dictionnaire de l'ancien français. Paris: Larousse. ISBN 2-03-340-302-5.

- ^ Hoad, T. F. (1986), English Etymology, Oxford University Press

- ^ Arce, Ignacio (2008). "Qasr Hallabat, Qasr Bshir and Deir el Kahf. Building Techniques, Architectural Typology and Change of Use of Three Quadriburgia from the Limes Arabicus. Interpretation and Significance.". Arqueología de la construcción II - los procesos constructivos en el mundo romano: Italia y provincias orientales. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 455–481.

- ^ Brown, R. Allen (2004) [1954]. Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 66. doi:10.1017/9781846152429. ISBN 1-84383-069-8.

- ^ Mesqui, Jean (1997). Châteaux forts et fortifications en France (in French). Paris: Flammarion. p. 493. ISBN 2-08-012271-1.